The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia

By Alfred W. McCoy with

Cathleen B. Read

and Leonard P.Adams II

4.

Cold War Opium Boom

It is March or April, the end of the dry season, in Southeast Asia's Golden Triangle. From

the Kachin hills and Shan plateau of Burma to the mountains of northern Thailand and

northern Laos, the ground is parched and the rains are only weeks away. In every hill

tribe village-whether it be Meo, Yao, Lahu, Lisu, Wa, or Kachin-it is time to clear the

fields for planting. On one of these hot, dusty mornings men, women, and children gather

at the bottom of a wide hillside near the village, where for weeks the men have been

chopping and slashing at the forest growth with single-bited axes The felled trees are

tinderbox dry,

Suddenly, the young men of the village race down the hill, igniting the timber with

torches. Behind them, whirlwinds of flame shoot four hundred feet into the sky. Within

the hour a billowing cloud of smoke rises two miles above the field. When the fires die

down, the fields are covered with a nourishing layer of wood ash and the soil's moisture

is sealed beneath the ground's fire-hardened surface. But before the planting can begin,

these farmers must decide what crop they are going to plant-rice or poppies?

Although their agricultural techniques hearken back to the Stone Age, these mountain

farmers are very much a part of the modern world. And like farmers everywhere their

basic economic decisions are controlled by larger forces-by the international market for commodities and the prices of manufactured goods. In their case the high cost of

transportation to and from their remote mountain villages rules out most cash crops and

leaves only two choices--opium or rice. The safe decision has always been to plant rice,

since it can always be eaten if the market fails. A farmer can cultivate a small patch of

poppy on the side, but he will not commit his full time to opium production unless he is

sure that there is a market for his crop.

A reliable market for their opium had developed in the early 1950's, when several major

changes in the international opium trade slowed, and then halted, the imports of Chinese

and Iranian opium that had supplied Southeast Asia's addicts for almost a hundred years.

Then the Thai police, the Chinese Nationalist Army and French and American

intelligence agencies allowed the mass narcotics addiction fostered by European

colonialism to survive-and even thrive-in the 1950's by deliberately or inadvertently

promoting local poppy cultivation in the Golden Triangle.

As a result of the activities of these various military and intelligence agencies, Southeast

Asia was completely self-sufficient in opium and had almost attained its present level of

production by the end of the decade. Recent research by the U.S. Bureau of Narcotics has

shown that by the late 1950's Southeast Asia's Golden Triangle region was producing

approximately seven hundred tons of raw opium, or about 50 percent of the world's total

illicit production. (1)

The Meo of Indochina had long been the subject of pressures for large-scale poppy

cultivation. During World War II the French colonial government was cut off from

international supplies, and had, as has already been mentioned, imposed an opium tax to

force the Meo of Laos and Tonkin to expand their opium production to meet wartime

needs. But in 1948 the French government responded to international pressure by

mounting a five-year campaign to abolish opium smoking in Indochina. However, French

intelligence agencies, short of funds to finance their clandestine operations against the

Communist Viet Minh, quickly and secretly took over the narcotics traffic.

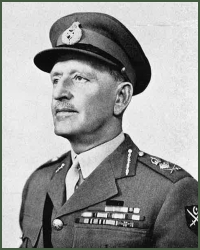

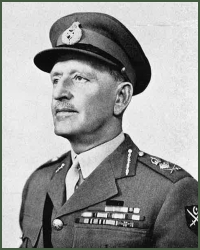

General Phao

In the Burma-Thailand area, during the early 1950's the CIA tried to use remnants of the

defeated Chinese Nationalist Army (Kuomintang, or K.M.T) in an attempt to seal the

Burma-China borderlands against a feared Chinese invasion of Southeast Asia.

Nationalist troops turned out to be better opium traders than guerrillas, and used their

American-supplied arms to force the Burmese hill tribes to expand production. They

shipped the bumper harvests to northern Thailand, where they were sold to the Thai

police force, which, coincidentally, was another CIA client. Under the direction of their

commander, General Phao, the police used CIA-supplied equipment to transport the

opium to Bangkok for export to the new markets of Malaysia, Indonesia, and Hong

Kong. In 1954 a British customs officer in Singapore stated that Bangkok had become the

opium capital of Asia and was distributing 30 percent of the region's opium. There was so

much Burmese and Thai opium on the illicit market that it was selling for 25 percent less

than Iranian opium and 40 percent less than the famous Indian brands. (2)

Southeast Asia's opium trade had come a long way in 150 years: close to a million

addicts provided a local market for opium and its derivatives; well-organized syndicates,

their personnel mainly drawn from military and intelligence communities, provided the

organizational expertise to move opium from the mountain fields to urban consumer

markets; and an ample number of skilled highland cultivators were now devoting most of

their agricultural labor to poppy cultivation. Although the region still exported only

limited amounts of opium, morphine, and heroin to Europe and the United States, the

region's narcotics trade was well enough developed by the late 1950's to meet any

demands for more substantial shipments.

French Indochina: Opium

Espionage and "Operation X"

The French colonial government's campaign gradually to eliminate opium addiction,

which began in 1946 with the abolition of the Opium Monopoly, never had a chance of

success. Desperately short of funds, French intelligence and paramilitary agencies took

over the opium traffic in order to finance their covert operations during the First

Indochina War (1946-1954). As soon as the civil administration would abolish some

aspect of the trade, French intelligence services proceeded to take it over. By 1951 they

controlled most of the opium trade-from the mountain poppy fields to the urban smoking

dens. Dubbed "Operation X" by insiders, this clandestine opium traffic produced a legacy

of Corsican narcotics syndicates and corrupted French intelligence officers who remain

even today key figures in the international narcotics trade.

The First Indochina War was a bitter nine-year struggle between a dying French colonial

empire and an emerging Vietnamese nation. It was a war of contrasts. On one side was

the French Expeditionary Corps, one of the proudest, most professional military

organizations in the world, with a tradition going back more than three hundred years to

the time of Louis XIV. Arrayed against it was the Viet Minh, an agglomeration of weak

guerrilla bands, the oldest of which had only two years of sporadic military experience

when the war broke out in 1946. The French commanders struck poses of almost fictional

proportions: General de Lattre, the gentleman warrior; Gen. Raoul Salan, the hardened

Indochina hand; Maj. Roger Trinquier, the cold-blooded, scientific tactician; and Capt.

Antoine Savani, the Corsican Machiavelli. The Viet Minh commanders were shadowy

figures, rarely emerging into public view, and when they did, attributing their successes

to the correctness of the party line or the courage of the rank and file. French military

publicists wrote of the excellence of this general's tactical understanding or that general's

brilliant maneuvers, while the Viet Minh press projected socialist caricatures of

struggling workers and peasants, heroic front-line fighters, and party wisdom.

These superficialities were indicative of the profound differences in the two armies. At

the beginning of the war the French high command viewed the conflict as a tactical

exercise whose outcome would be determined, according to traditional military doctrines,

by controlling territory and winning battles. The Viet Minh understood the war in

radically different terms; to them, the war was not a military problem, it was a political

one. As the Viet Minh commander, Gen. Vo Nguyen Giap, has noted: "political activities were more important than military activities, and fighting less important than

propaganda; armed activity was used to safeguard, consolidate, and develop political

bases." (3)

The Viet

Minh's goal

was to develop

a political

program that

would draw the

entire

population regardless

of

race, religion,

sex, or class

background into

the

struggle for

national

liberation.

Theirs was a

romantic vision

of the mass

uprising:

resistance

becoming so

widespread and

so intense that

the French

would be

harassed

everywhere.

Once the front line

troops and

the masses in

the rear were

determined to

win, the tactical

questions of

how to apply

this force were rather elementary.

The French suffered through several years of frustrating stalemate before realizing that

their application of classical textbook precepts was losing the war. But they slowly

developed a new strategy of counter guerrilla, or counterinsurgency, warfare. By 1950-

1951 younger, innovative French officers had abandoned the conventional war precepts that essentially visualized Indochina as a depopulated staging ground for fortified lines,

massive sweeps, and flanking maneuvers. Instead Indochina became a vast chessboard

where hill tribes, bandits, and religious minorities could be used as pawns to hold certain

territories and prevent Viet Minh infiltration. The French concluded formal alliances with

a number of these ethnic or religious factions and supplied them with arms and money to

keep the Viet Minh out of their area. The French hope was to atomize the Viet Minh's

mobilized, unified mass into a mosaic of autonomous fiefs hostile to the revolutionary

movement.

Maj. Roger Trinquier and Capt. Antoine Savani were the most important apostles of this

new military doctrine. Captain Savani secured portions of Cochin China (comprising

Saigon and the Mekong Delta) by rallying river pirates, Catholics, and messianic

religious cults to the French side. Along the spine of the Annamite Mountains from the

Central Highlands to the China border, Major Trinquier recruited an incredible variety of hill tribes; by 1954 more than forty thousand tribal mercenaries were busy ambushing

Viet Minh supply lines, safeguarding territory, and providing intelligence. Other French

officers organized Catholic militia from parishes in the Tonkin Delta, Nung pirates on the

Tonkin Gulf, and a Catholic militia in Hue.

Although the French euphemistically referred to these local troops as "supplementary

forces" and attempted to legitimize their leaders with ranks, commissions, and military

decorations, they were little more than mercenaries and very greedy, very expensive

mercenaries at that. To ensure the loyalty of the Binh Xuyen river pirates who guarded

Saigon, the French allowed them to organize a variety of lucrative criminal enterprises

and paid them an annual stipend of $85,000 as well. (4) Trinquier may have had forty

thousand hill tribe guerrillas under his command by 1954, but he also had to pay dearly

for their services: he needed an initial outlay of $15,000 for basic training, arms, and

bonuses to set up each mercenary unit of 150 men. (5) It is no exaggeration to say that the

success of Savani's and Trinquier's work depended almost entirely on adequate financing;

if they were well funded they could expand their programs almost indefinitely, but

without capital they could not even begin.

But the counterinsurgency efforts were continually plagued by a lack of money. The war

was tremendously unpopular in France, and the French National Assembly reduced its

outlay to barely enough for the regular military units, leaving almost nothing for extras

such as paramilitary or intelligence work. Moreover, the high command itself never really

approved of the younger generation's unconventional approach and were unwilling to

divert scarce funds from the regular units. Trinquier still complains that the high

command never understood what he was trying to do, and says that they consistently

refused to provide sufficient funds for his operations. (6)

The solution was "Operation X," a clandestine narcotics traffic so secret that only high ranking

French and Vietnamese officials even knew of its existence. The anti opium drive

that began in 1946 received scant support from the "Indochina hands"; customs officials

continued to purchase raw opium from the Meo, and the opium smoking dens,

cosmetically renamed "detoxification clinics," continued to sell unlimited quantities of opium.' However, on September 3, 1948, the French high commissioner announced that

each smoker had to register with the government, submit to a medical examination to

ascertain the degree of his addiction, and then be weaned of the habit by having his

dosage gradually reduced. (8) Statistically the program was a success. The customs

service had bought sixty tons of raw opium from the Meo and Yao in 1943, but in 1951

they purchased almost nothing? (9) The "detoxification clinics" were closed and the

hermetically sealed opium packets each addict purchased from the customs service

contained a constantly dwindling amount of opium. (10)

But the opium trade remained essentially unchanged. The only real differences were that

the government, having abandoned opium as a source of revenue, now faced serious

budgetary problems; and the French intelligence community, having secretly taken over

the opium trade, had all theirs solved. The Opium Monopoly had gone underground to

become "Operation X."

Unlike the American CIA, which has its own independent administration and chain of

command, French intelligence agencies have always been closely tied to the regular

military hierarchy. The most important French intelligence agency, and the closest

equivalent to the CIA, is the S.D.E.C.E (Service de Documentation Exterieure et du ContreEspionage).

During the First Indochina War, its Southeast Asian representative, Colonel

Maurice Belleux, supervised four separate S.D.E.C.E "services" operating inside the war

zone-intelligence, decoding, counterespionage, and action (paramilitary operations).

While S.D.E.C.E was allowed a great deal of autonomy in its pure intelligence work-spying,

decoding, and counterespionage-the French high command assumed much of the

responsibility for S.D.E.C.E's paramilitary Action Service. Thus, although Major Trinquier's

hill tribe guerrilla organization, the Mixed Airborne Commando Group (M.A.C.G), was

nominally subordinate to S.D.E.C.E's Action Service, in reality it reported to the

Expeditionary Corps' high command. All of the other paramilitary units, including

Captain Savani's Binh Xuyen river pirates, Catholics, and armed religious groups,

reported to the 2eme Bureau, the military intelligence bureau of the French Expeditionary

Corps.

During its peak years from 1951 to 1954, Operation X was sanctioned on the highest

levels by Colonel Belleux for S.D.E.C.E and Gen. Raoul Salan for the Expeditionary Corps.

(11) Below them, Major Trinquier of M.A.C.G assured Operation X a steady supply of

Meo opium by ordering his liaison officers serving with Meo commander Touby Lyfoung

and Tai Federation leader Deo Van Long to buy opium at a competitive price. Among the

various French paramilitary agencies, the work of the Mixed Airborne Command Group

(M.A.C.G) was most inextricably interwoven with the opium trade, and not only in order to

finance operations. For its field officers in Laos and Tonkin had soon realized that unless

they provided a regular outlet for the local opium production, the prosperity and loyalty

of their hill tribe allies would be undermined.

Once the opium was collected after the annual spring harvest, Trinquier had the mountain

guerrillas fly it to Cap Saint Jacques (Vungtau) near Saigon, where the Action Service

school trained hill tribe mercenaries at a military base. There were no customs or police controls to interfere with or expose the illicit shipments here. From Cap Saint Jacques the

opium was trucked the sixty miles into Saigon and turned over to the Binh Xuyen

bandits, who were there serving as the city's local militia and managing its opium traffic,

under the supervision of Capt. Antoine Savani of the 2eme Bureau. (12)

The Binh Xuyen operated two major opium-boiling plants in Saigon (one near their headquarters at Cholon's Y-Bridge and the other near the National Assembly) to transform the raw poppy sap into a smokable form. The bandits distributed the prepared opium to dens and retail shops throughout Saigon and Cholon, some of which were owned by the Binh Xuyen (the others paid the gangsters a substantial share of their profits for protection). The Binh Xuyen divided its receipts with Trinquier's M.A.C.G and Savani's 2eme Bureau. (13) Any surplus opium the Binh Xuyen were unable to market was sold to local Chinese merchants for export to Hong Kong or else to the Corsican criminal syndicates in Saigon for shipment to Marseille. M.A.C.G deposited its portion in a secret account managed by the Action Service office in Saigon. When Touby Lyfoung or any other Meo tribal leader needed money, he flew to Saigon and personally drew money out of the caisse noire, or black box. (13)

M.A.C.G had had its humble beginnings in 1950 following a visit to Indochina by the S.D.E.C.E deputy director, who decided to experiment with using hill tribe warriors as mountain mercenaries. Colonel Grail was appointed commander of the fledgling unit, twenty officers were assigned to work with hill tribes in the Central Highlands, and a special paramilitary training camp for hill tribes, the Action School, was established at Cap Saint Jacques. (14) However, the program remained experimental until December 1950, when Marshal Jean de Lattre de Tassigny was appointed commander in chief of the Expeditionary Corps. Realizing that the program had promise, General de Lattre transferred 140 to 150 officers to M.A.C.G, and appointed Maj. Roger Trinquier to command its operations in Laos and Tonkin. (15) Although Grail remained the nominal commander until 1953, it was Trinquier who developed most of MACG's innovative counterinsurgency tactics, forged most of the important tribal alliances, and organized much of the opium trade during his three years of service. (16)

His program for organizing country guerrilla units in Tonkin and Laos established him as a leading international specialist in counterinsurgency warfare. He evolved a precise four point method for transforming any hill tribe area in Indochina from a scattering of mountain hamlets into a tightly disciplined, counter guerrilla infrastructure-a maquis. Since his theories also fascinated the CIA and later inspired American programs in Vietnam and Laos, they bear some examination.

PRELIMINARY STAGE. A small group of carefully selected officers fly over hill tribe villages in a light aircraft to test the response of the inhabitants. If somebody shoots at the aircraft, the area is probably hostile, but if the tribesmen wave, then the area might have potential. [a 1951, for example, Major Trinquier organized the first maquis in Tonkin by repeatedly flying over Meo villages northwest of Lai Chan until he drew a response. When some of the Meo waved the French tricolor, he realized the area qualified for stage. (17)

STAGE 1. Four or five M.A.C.G commandos were parachuted into the target area to recruit about fifty local tribesmen for counter guerrilla training at the Action School in Cap Saint Jacques, where up to three hundred guerrillas could be trained at a time. Trinquier later explained his criterion for selecting these first tribal cadres:

They are doubtless more attracted by the benefits they can expect than by our country itself, but this attachment can be unflagging if we are resolved to accept it and are firm in our intentions and objectives. We know also that, in troubled periods, self-interest and ambition have always been powerful incentives for dynamic individuals who want to move out of their rut and get somewhere. (18)

These ambitious mercenaries were given a forty-day commando course comprising airborne training, radio operation, demolition, small arms use, and counterintelligence. Afterward the group was broken up into four-man teams comprised of a combat commander, radio operator, and two intelligence officers. The teams were trained to operate independently of one another so that the maquis could survive were any of the teams captured. Stage I took two and a half months, and was budgeted at $3,000.

STAGE 2. The original recruits returned to their home area with arms, radios, and money to set up the maquis. Through their friends and relatives, they began propagandizing the local population and gathering basic intelligence about Viet Minh activities in the area. Stage 2 was considered completed when the initial teams had managed to recruit a hundred more of their fellow tribesmen for training at Cap Saint Jacques. This stage usually took about two months and $6,000, with most of the increased expenses consisting of the relatively high salaries of these mercenary troops.

STAGE 3 was by far the most complex and critical part of the entire process. The target area was transformed from an innocent scattering of mountain villages into a tightly controlled maquis. After the return of the final hundred cadres, any Viet Minh organizers in the area were assassinated, a tribal leader "representative of the ethnic and geographic group predominant in the zone" was selected, and arms were parachuted to the hill tribesmen. If the planning and organization had been properly carried out, the maquis would have up to three thousand armed tribesmen collecting intelligence, ferreting out Viet Minh cadres, and launching guerrilla assaults on nearby Viet Minh camps and supply lines. Moreover, the maquis was capable of running itself, with the selected tribal leader communicating regularly by radio with French liaison officers in Hanoi or Saigon to assure a steady supply of arms, ammunition, and money.

While the overall success of this program proved its military value, the impact on the French officer corps revealed the dangers inherent in clandestine military operations that allow its leaders carte blanche to violate any or all military regulations and moral laws. The Algerian war, with its methodical torture of civilians, continued the inevitable brutalization of France's elite professional units. Afterward, while his comrades in arms were bombing buildings and assassinating government leaders in Paris in defiance of President de Gaulle's decision to withdraw from Algeria, Trinquier, who had directed the torture campaign during the battle for Algiers, flaunted international law by organizing Katanga's white mercenary army to fight a U.N. peace-keeping force during the 1961 Congo crisis. (19) Retiring to France to reflect, Trinquier advocated the adoption of "calculated acts of sabotage and terrorism, (20) and Systematic duplicity in international dealings as an integral part of national defense policy. (21) While at first glance it may seem incredible that the French military could have become involved in the Indochina narcotics traffic, in retrospect it can be understood as just another consequence of allowing men to do whatever seems expedient.

Trinquier had developed three important counter guerrilla maquis for M.A.C.G in northeast

Laos and Tonkin during 1950-1953: the Meo maquis in Laos under the command of

Touby Lyfoung; the Tai maquis under Deo Van Long in northwestern Tonkin; and the

Meo maquis east of the Red River in north central Tonkin. Since opium was the only

significant economic resource in each of these three regions, M.A.C.G's opium purchasing

policy was just as important as its military tactics in determining the effectiveness of

highland counterinsurgency programs. Where M.A.C.G purchased the opium directly from

the Meo and paid them a good price, they remained loyal to the French. But when the

French used non-Meo highland minorities as brokers and did nothing to prevent the Meo

from being cheated, the Meo tribesmen joined the Viet Minh-with disastrous

consequences for the French.

Trinquier had developed three important counter guerrilla maquis for M.A.C.G in northeast

Laos and Tonkin during 1950-1953: the Meo maquis in Laos under the command of

Touby Lyfoung; the Tai maquis under Deo Van Long in northwestern Tonkin; and the

Meo maquis east of the Red River in north central Tonkin. Since opium was the only

significant economic resource in each of these three regions, M.A.C.G's opium purchasing

policy was just as important as its military tactics in determining the effectiveness of

highland counterinsurgency programs. Where M.A.C.G purchased the opium directly from

the Meo and paid them a good price, they remained loyal to the French. But when the

French used non-Meo highland minorities as brokers and did nothing to prevent the Meo

from being cheated, the Meo tribesmen joined the Viet Minh-with disastrous

consequences for the French.

Unquestionably, the most successful M.A.C.G operation was the Meo maquis in Xieng Khouang Province, Laos, led by the French-educated Meo Touby Lyfoung. When the Expeditionary Corps assumed responsibility for the opium traffic on the Plain of Jars in 1949-1950, they appointed Touby their opium broker, as had the Opium Monopoly before them. (22) Major Trinquier did not need to use his four-stage plan when dealing with the Xieng Khoung Province Meo; soon after he took command in 1951, Touby came to Hanoi to offer to help initiate M.A.C.G commando operations among his Meo followers. Because there had been little Viet Minh activity near the Plain of Jars since 1946, both agreed to start slowly by sending a handful of recruits to the Action School for radio instruction. (23) Until the Geneva truce in 1954 the French military continued to pay Touby an excellent price for the Xieng Khouang opium harvest, thus assuring his followers' loyalty and providing him with sufficient funds to influence the course of Meo politics. This arrangement also made Touby extremely wealthy by Meo standards, In exchange for these favors, Touby remained the most loyal and active of the hill tribe commanders in Indochina.

Touby proved his worth during the 1953-1954 Viet Minh offensive. In December 1952 the Viet Minh launched an offensive into the Tai country in northwestern Tonkin (North Vietnam), and were moving quickly toward the Laos-Vietnam border when they ran short of supplies and withdrew before crossing into Laos. (24) But since rumors persisted that the Viet Minh were going to drive for the Mekong the following spring, an emergency training camp was set up on the Plain of Jars and the first of some five hundred young Meo were flown to Cap Saint Jacques for a crash training program. Just as the program was getting underway, the Viet Minh and Pathet Lao (the Lao national liberation movement) launched a combined offensive across the border into Laos, capturing Sam Neua City on April 12, 1953. The Vietnam 316th People's Army Division, Pathet Lao irregulars, and local Meo partisans organized by Lo Faydang drove westward, capturing Xieng Khouang City two weeks later. But with Touby's Meo irregulars providing intelligence and covering their mountain flanks, French and Lao colonial troops used their tanks and artillery to good advantage on the flat Plain of Jars and held off the Pathet Lao-Viet Minh units. (25)

In May the French Expeditionary Corps built a steel mat airfield on the plain and began airlifting in twelve thousand troops, some small tanks, and heavy engineering equipment. Under the supervision of Gen. Albert Sore, who arrived in June, the plain was soon transformed into a virtual fortress guarded by forty to fifty reinforced bunkers and blockhouses. Having used mountain minorities to crush rebellions in Morocco, Sore appreciated their importance and met with Touby soon after his arrival. After an aerial tour of the region with Touby and his M.A.C.G adviser, Sore sent out four columns escorted by Touby's partisans to sweep Xieng Khouang Province clean of any remaining enemy units. After this, Sore arranged with Touby and M.A.C.G that the Meo would provide intelligence and guard the mountain approaches while his regular units garrisoned the plain itself. The arrangement worked well, and Sore remembers meeting amicably on a regular basis with Touby and Lieut. Vang Pao, then company commander of a Meo irregular unit (and now commander of CIA mercenaries in Laos), to exchange intelligence and discuss paramilitary operations. He also recalls that Touby delivered substantial quantities of raw opium to M.A.C.G advisers for the regular DC-3 flights to Cap Saint Jacques, and feels that the French support of the Meo opium trade was a major factor in their military aggressiveness. As Sore put it, "The Meo were defending their own region, and of course by defending their region they were defending their opium." (26)

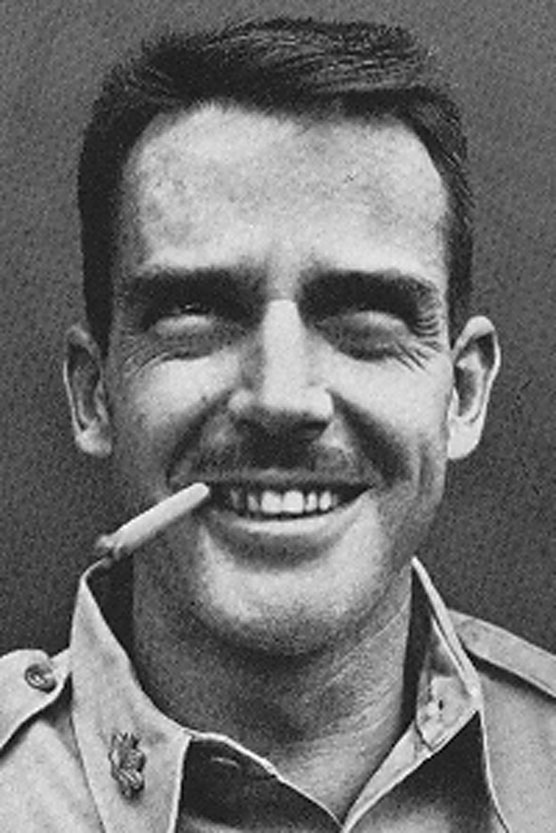

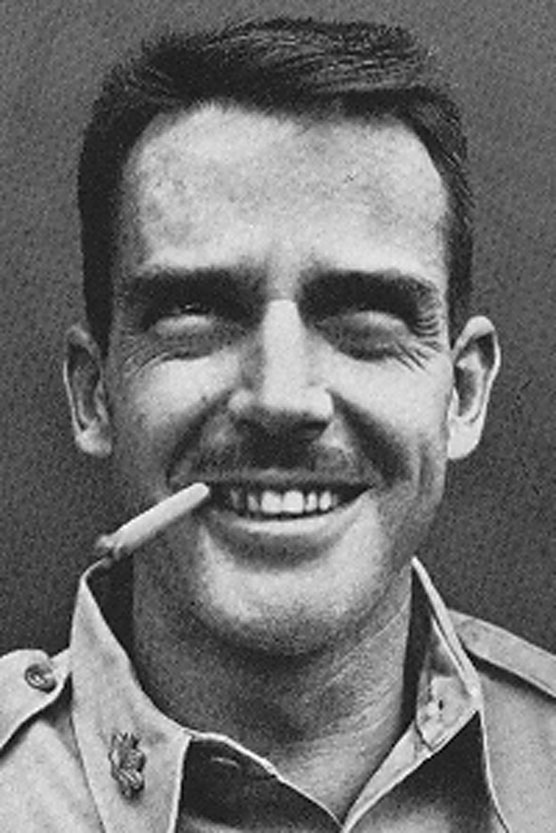

Another outsider also witnessed the machinations of the covert Operation X. During a

six-week investigative tour of Indochina during June/July 1953, Col. Edward 0. Lansdale

of the American CIA discovered the existence of Operation X. Trying to put together a

firsthand report of the Viet Minh invasion of Laos, Lansdale flew up to the Plain of Jars,

where he learned that French officers had bought up the 1953 opium harvest, acting on

orders from General Salan, commander in chief of the Expeditionary Corps. When

Lansdale later found out that the opium had been flown to Saigon for sale and export, he

complained to Washington that the French military was involved in the narcotics traffic

and suggested that an investigation was in order. General Lansdale recalls that the

response ran something like this:

Another outsider also witnessed the machinations of the covert Operation X. During a

six-week investigative tour of Indochina during June/July 1953, Col. Edward 0. Lansdale

of the American CIA discovered the existence of Operation X. Trying to put together a

firsthand report of the Viet Minh invasion of Laos, Lansdale flew up to the Plain of Jars,

where he learned that French officers had bought up the 1953 opium harvest, acting on

orders from General Salan, commander in chief of the Expeditionary Corps. When

Lansdale later found out that the opium had been flown to Saigon for sale and export, he

complained to Washington that the French military was involved in the narcotics traffic

and suggested that an investigation was in order. General Lansdale recalls that the

response ran something like this:

"Don't you have anything else to do? We don't want you to open up this keg of worms since it will be a major embarrassment to a friendly government. So drop your investigation." (27)

By mid 1953, repeated Viet Minh offensives into northern Laos, like the spring assault on the Plain of Jars, had convinced the French high command that they were in imminent danger of losing all of northern Laos. To block future Viet Minh offensives, they proceeded to establish a fortified base, or "hedgehog," in a wide upland valley called Dien Bien Phu near the Laos-North Vietnam border. (28) In November the French air force and C.A.T (Civil Air Transport, later Air America) began airlifting sixteen thousand men into the valley, and French generals confidently predicted they would soon be able to seal the border.

By March 1954, however, the Viet Minh had ringed Dien Bien Phu with well entrenched heavy artillery; within a month they had silenced the French counter batteries. Large-scale air evacuation was impossible, and the garrison was living on borrowed time. Realizing that an overland escape was their only solution, the French high command launched a number of relief columns from northern Laos to crack through the lines of entrapment and enable the defenders to break out. (29) Delayed by confusion in high command headquarters, the main relief column of 3,000 men did not set out until April 14. (30) As the relief column got underway, Colonel Trinquier, by now M.A.C.G commander, proposed a supplementary plan for setting up a large maquis, manned by Touby's irregulars, halfway between Dien Bien Phu and the Plain of Jars to aid any of the garrison who might break out. After overcoming the high command's doubts, Trinquier flew to the Plain of Jars with a large supply of silver bars. Half of Touby's 6,000 irregulars were given eight days of intensive training and dispatched for Muong Son, sixty miles to the north, on May 1. But although Trinquier managed to recruit yet another 1,500 Meo mercenaries elsewhere, his efforts proved futile. (31) Dien Bien Phu fell on May 8, and only a small number of the seventy-eight colonial troops who escaped were netted by Touby's maquis. (32)

Unlike the Meo in Laos, the Meo in northwestern Tonkin, where Dien Bien Phu was located, had good cause to hate the French, and were instrumental in their defeat. Although in Laos Operation X had purchased raw opium directly from the Meo leaders, in northwestern Tonkin political considerations forced M.A.C.G officials to continue the earlier Opium Monopoly policy of using Tai leaders, particularly Deo Van Long, as their intermediaries with the Meo opium cultivators. By allowing the Tai feudal lords to force the Meo to sell their opium to Tai leaders at extremely low prices, they embittered the Meo toward the French even more and made them enthusiastic supporters of the Viet Minh.

When the Vietnamese revolution began in 1945 and the French position weakened throughout Indochina, the French decided to work through Deo Van Long, one of the few local leaders who had remained loyal, to restore their control over the strategically important Tai highlands in northwestern Tonkin. (33) In 1946 three highland provinces were separated from the rest of Tonkin and designated an autonomous Tai Federation, with Deo Van Long, who had only been the White Tai leader of Lai Chau Province, as president. Ruling by fiat, he proceeded to appoint his friends and relatives to every possible position of authority. (34) However, since there were only 25,000 White Tai in the federation as opposed to 100,000 Black Tai and 50,000 Meo, (35) his actions aroused bitter opposition.

When political manipulations failed, Deo Van Long tried to put down the dissidence by military force, using two 850-man Tai battalions that had been armed and trained by the French. Although he drove many of the dissidents to take refuge in the forests, this was hardly a solution, since they made contact with the Viet Minh and thus became an even greater problem. (36)

Moreover, French support for Deo Van Long's fiscal politics was a disaster for France's entire Indochina empire. The French set up the Tai Federation's first autonomous budget in 1947, based on the only marketable commodity-Meo opium. As one French colonel put it:

"The Tai budgetary receipts are furnished exclusively by the Meo who pay half with their raw opium, and the other half, indirectly, through the Chinese who lose their opium smuggling profits in the [state] gaming halls."(37)

Opium remained an important part of the Tai Federation budget until 1951, when a young adviser to the federation, Jean Jerusalemy, ordered it eliminated. Since official regulations prohibited opium smoking, Jerusalemy, a strict bureaucrat, did not understand how the Tai Federation could be selling opium to the government.

So in 1951 opium disappeared from the official budget. Instead of selling it to the customs service, Deo Van Long sold it to M.A.C.G officers for Operation X. In the same year French military aircraft began making regular flights to Lai Chau to purchase raw opium from Deo Van Long and local Chinese merchants for shipment to Hanoi and Saigon.(38)

With the exception of insignificant quantities produced by a few Tai villages, almost all of the opium purchased was grown by the fifty thousand Meo in the federation. During the Second World War and the immediate postwar years, they sold about 4.5 to 5.0 tons of raw opium annually to Deo Van Long's agents for the Opium Monopoly. Since the Monopoly paid only one-tenth of the Hanoi black market price, the Meo preferred to sell the greater part of their harvest to the higher-paying local Chinese smugglers. (39) During this time, Deo Van Long had no way to force the Meo to sell to his agents at the low official price. However, in 1949, now with three Tai guerrilla battalions, and with his retainers in government posts in all of the lowland trading centers, he was in a position to force the Meo to sell most of their crop to him, at gun point, if necessary. (40) Many of the Meo who had refused to sell at his low price became more cooperative when confronted with a squad of well-armed Tai guerrillas. And when he stopped dealing with the Opium Monopoly after 1950, there was no longer any official price guideline, and he was free to increase his own profits by reducing the already miserable price paid the Meo.

While these methods may have made Deo Van Long a rich man by the end of the Indochina War (after the Geneva cease-fire he retired to a comfortable villa in France), they seriously damaged his relations with the Meo. When they observed his rise in 1945- 1946 as the autocrat of the Tai Federation, many joined the Viet Minh. (41) As Deo Van Long acquired more arms and power in the late 1940's and early 1950's, his rule became even more oppressive, and the Meo became even more willing to aid the Viet Minh.

This account of the Tai Federation opium trade would be little more than an interesting footnote to the history of the Indochina Opium Monopoly were it not for the battle of Dien Bien Phu. Although an ideal base from a strategic viewpoint, the French command could not have chosen a more unfavorable battlefield. It was the first Black Tai area Deo Van Long had taken control of after World War II. His interest in it was understandable: Dien Bien Phu was the largest valley in the Tai Federation and in 1953 produced four thousand tons of rice, about 30 (42) percent of the Federation's production. Moreover, the Meo opium cultivators in the surrounding hills produced three-fifths of a ton of raw opium for the monopoly, or about 13 percent of the federation's legitimate sale. (43) But soon after tile first units were parachuted into Dien Bien Phu, experienced French officials in the Tai country began urging the high command to withdraw from the area. The young French adviser, Jean Jerusalemy, sent a long report to the high command warning them that if they remained at Dien Bien Phu defeat was only a matter of time. The Meo in the mountain area were extremely bitter toward Deo Van Long and the French for their handling of the opium crop, explained Jerusalemy, and the Black Tai living on the valley floor still resented the imposition of White Tai administrators.(44)

Confident that the Viet Minh could not possibly transport sufficient heavy artillery through the rough mountain terrain, the French generals ignored these warnings. French and American artillery specialists filed reassuring firsthand reports that the "hedgehog" was impenetrable. When the artillery duel began in March 1954, French generals were shocked to find themselves outgunned; the Viet Minh had two hundred heavy artillery pieces with abundant ammunition, against the French garrison's twenty-eight heavy guns and insufficient ammunition. (45) An estimated eighty thousand Viet Minh porters had hauled this incredible firepower across the mountains, guided and assisted by enthusiastic Black Tai and Meo. Gen. Vo Nguyen Giap, the Viet Minh commander, recalls that "convoys of pack horses from the Meo highlands" were among the most determined of the porters who assisted this effort. (46)

Meo hostility prevented French intelligence gathering and counterintelligence operations. It is doubtful that the Viet Minh would have chosen to attack Dien Bien Phu had they been convinced that the local population was firmly against them, since trained Meo commandos could easily have disrupted their supply lines, sabotaged their artillery, and perhaps given the French garrison accurate intelligence on their activities. As it was, Colonel Trinquier tried to infiltrate five MACG commando teams from Laos into the Dien Bien Phu area, but the effort was almost a complete failure. (47)Unfamiliar with the terrain and lacking contacts with the local population, the Laotian Meo were easily brushed aside by Viet Minh troops with local Meo guides. The pro-Viet Minh Meo enveloped a wide area surrounding the fortress, and all of Trinquier's teams were discovered before they even got close to the encircled garrison. The Viet Minh divisions overwhelmed the garrison on May 7-8, 1954.

Less than twenty-four hours later, on May 8, 1954, Vietnamese, French, Russian, Chinese, British, and American delegates sat down together for the first time at Geneva, Switzerland, to discuss a peace settlement. The news from Dien Bien Phu had arrived that morning, and it was reflected in the grim faces of the Western delegates and the electric confidence of the Vietnamese. (48) The diplomats finally compromised on a peace agreement almost three months later: on July 20 an armistice was declared and the war was over.

But to Col. Roger Trinquier a multilateral agreement signed by a host of great and small powers meant nothing-his war went on. Trinquier had forty thousand hill tribe mercenaries operating under the command of four hundred French officers by the end of July and was planning to take the war to the enemy by organizing a huge new maquis of up to ten thousand tribesmen in the Viet Minh heartland east of the Red River. (49) Now he was faced with a delicate problem: his mercenaries had no commissions, no official status, and were not covered by the cease-fire. The Geneva agreement prohibited overflights by the light aircraft Trinquier used to supply his mercenery units behind Viet Minh lines and thus created insurmountable logistics and liaison problems. (50) Although he was able to use some of the Red Cross flights to the prisoner-of-war camps in the Viet Minh-controlled highlands as a cover for arms and ammunition drops, this was only a stopgap measure. (51) In August, when Trinquier radioed his remaining MACG units in the Tai Federation to fight their way out into Laos, several thousand Tai retreated into Sam Neua and Xieng Khouang provinces, where they were picked up by Touby Lyfoung's Meo irregulars. But the vast majority stayed behind, and although some kept broadcasting appeals for arms, money, and food, by late August their radio batteries went dead, and they were never heard from again.

There was an ironic footnote to this last M.A.C.G operation. Soon after several thousand of the Tai Federation commandos arrived in Laos, Touby realized that it would take a good deal of money to resettle them permanently. Since the M.A.C.G secret account had netted almost $150,000 from the last winter's opium harvest, Touby went to the Saigon paramilitary office to make a personal appeal for resettlement funds. But the French officer on duty was embarrassed to report that an unknown M.A.C.G or S.D.E.C.E officer had stolen the money, and M.A.C.G's portion of Operation X was broke. "Trinquier told us to put the five million piasters in the account where it would be safe," Touby recalls with great amusement, "and then one of his officers stole it. What irony! What irony!". (52)

When the French Expeditionary Corps began its rapid withdrawal from Indochina in 1955, M.A.C.G officers approached American military personnel and offered to turn over their entire paramilitary apparatus. CIA agent Lucien Conein was one of those contacted, and he passed the word along to Washington. But, "D.O.D [Department of Defense] responded that they wanted nothing to do with any French program" and the offer was refused. (53) But many in the Agency regretted the decision when the CIA sent Green Berets into Laos and Vietnam to organize hill tribe guerrillas several years later, and in 1962 American representatives visited Trinquier in Paris and offered him a high position as an adviser on mountain warfare in Indochina. But, fearing that the Americans would never give a French officer sufficient authority to accomplish anything, Trinquier refused. (54)

Looking back on the machinations of Operation X from the vantage point of almost two decades, it seems remarkable that its secret was so well kept. Almost every news dispatch from Saigon that discussed the Binh Xuyen alluded to their involvement in the opium trade, but there was no mention of the French support for hill tribe opium dealings, and certainly no comprehension of the full scope of Operation X. Spared the screaming headlines, or even muted whispers, about their involvement in the narcotics traffic, neither S.D.E.C.E nor the French military were pressured into repudiating the narcotics traffic as a source of funding for covert operations. Apparently there was but one internal investigation of this secret opium trade, which only handed out a few reprimands, more for indiscretion than anything else, and Operation X continued undisturbed until the French withdrew from Indochina.

The investigation began in 1952, when Vietnamese police seized almost a ton of raw opium from a M.A.C.G warehouse in Cap Saint Jacques. Colonel Belleux had initiated the seizure when three M.A.C.G officers filed an official report claiming that opium was being stored in the M.A.C.G warehouses for eventual sale. After the seizure confirmed their story, Belleux turned the matter over to Jean Letourneau, high commissioner for Indochina, who started a formal inquiry through the comptroller general for Overseas France. Although the inquiry uncovered a good deal of Operation X's organization, nothing was done. The inquiry did damage the reputation of M.A.C.G's commander, Colonel Grall, and Commander in Chief Salan. Grall was ousted from M.A.C.G and Trinquier was appointed as his successor in March 1953. (55)

Following the investigation, Colonel Belleux suggested to his Paris headquarters that S.D.E.C.E and M.A.C.G should reduce the scope of their narcotics trafficking. If they continued to control the trade at all levels, the secret might get out, damaging France's international relations and providing the Viet Minh with excellent propaganda. Since the French had to continue buying opium from the Meo to retain their loyalty, Belleux suggested that it be diverted to Bangkok instead of being flown directly to Saigon and Hanoi. In Bangkok the opium would become, indistinguishable from much larger quantities being shipped out of Burma by the Nationalist Chinese Army, and thus the French involvement would be concealed. S.D.E.C.E Paris, however, told Belleux that he was a "troublemaker" and urged him to give up such ideas. The matter was dropped. (56)

Apparently S.D.E.C.E and French military emerged from the Indochina War with narcotics trafficking as an accepted gambit in the espionage game. In November 1971, the U.S. Attorney for New Jersey caused an enormous controversy in both France and the United States when he indicted a high-ranking S.D.E.C.E officer, Col. Paul Fournier, for conspiracy to smuggle narcotics into the United States. Given the long history of S.D.E.C.E's official and unofficial involvement in the narcotics trade, shock and surprise seem to be unwarranted. Colonel Fournier had served with S.D.E.C.E in Vietnam during the First Indochina War at a time when the clandestine service was managing the narcotics traffic as a matter of policy. The current involvement of some S.D.E.C.E agents in Corsican heroin smuggling (see Chapter 2) would seem to indicate that S.D.E.C.E's acquaintance with the narcotics traffic has not ended.

While the history of S.D.E.C.E and M.A.C.G's direct involvement in the tribal opium trade

provides an exotic chapter in the history of the narcotics traffic, the involvement of

Saigon's Binh Xuyen river pirates was the product of a type of political relationship that

has been repeated with alarming frequency over the last half-century-the alliance between

governments and gangsters. Just as the relationship between the O.S.S and the Italian

Mafia during World War II and the CIA-Corsican alliance in the early years of the cold

war affected the resurrection of the European heroin trade, so the French 2eme Bureau's

alliance with the Binh Xuyen allowed Saigon's opium commerce to survive and prosper

during the First Indochina War. The 2eme Bureau was not an integral cog in the

mechanics of the traffic as M.A.C.G had been in the mountains; it remained in the

background providing overall political support, allowing the Binh Xuyen to take over the

opium dens and establish their own opium references. By 1954 the Binh Xuyen

controlled virtually all of Saigon's opium dens and dominated the distribution of prepared

opium throughout Cochin China (the southern part of Vietnam). Since Cochin China had

usually consumed over half of the monopoly's opium, and Saigon with its Chinese twin

city, Cholon-had the highest density of smokers in the entire colony, (57) the 2eme Bureau's

decision to turn the traffic over to the Binh Xuyen guaranteed the failure of the

government's anti opium campaign and ensured the survival of mass opium addiction in

Vietnam.

The 2eme Bureau's pact with the Binh Xuyen was part of a larger French policy of using

ethnic, religious, and political factions to deny territory to the Viet Minh. By supplying

these splinter groups with arms and money, the French hoped to make them strong

enough to make their localities into private fiefs, thereby neutralizing the region and

freeing regular combat troops from garrison duty. But Saigon was not just another clump

of rice paddies, it was France's "Pearl of the Orient," the richest, most important city in

Indochina. In giving Saigon to the Binh Xuyen, block by block, over a six-year period,

the French were not just building up another fiefdom, they were making these bandits the

key to their hold on all of Cochin China. Hunted through the swamps as river pirates in

the 1940's, by 1954 their military commander was director-general of the National Police

and their great chief, the illiterate Bay Vien, was nominated as prime minister of

Vietnam. The robbers had become the cops, the gangsters the government.

The 2eme Bureau's pact with the Binh Xuyen was part of a larger French policy of using

ethnic, religious, and political factions to deny territory to the Viet Minh. By supplying

these splinter groups with arms and money, the French hoped to make them strong

enough to make their localities into private fiefs, thereby neutralizing the region and

freeing regular combat troops from garrison duty. But Saigon was not just another clump

of rice paddies, it was France's "Pearl of the Orient," the richest, most important city in

Indochina. In giving Saigon to the Binh Xuyen, block by block, over a six-year period,

the French were not just building up another fiefdom, they were making these bandits the

key to their hold on all of Cochin China. Hunted through the swamps as river pirates in

the 1940's, by 1954 their military commander was director-general of the National Police

and their great chief, the illiterate Bay Vien, was nominated as prime minister of

Vietnam. The robbers had become the cops, the gangsters the government.

The Binh Xuyen river pirates first emerged in the early 1920's in the marshes and canals along the southern fringes of Saigon-Cholon. They were a loosely organized coalition of pirate gangs, about two hundred to three hundred strong. Armed with old rifles, clubs, and knives, and schooled in Sino-Vietnamese boxing, they extorted protection money from the sampans and junks that traveled the canals on their way to the Cholon docks. Occasionally they sortied into Cholon to kidnap, rob, or shake down a wealthy Chinese merchant. If too sorely pressed by the police or the colonial militia, they could retreat through the streams and canals south of Saigon deep into the impenetrable Rung Sat Swamp at the mouth of the Saigon River, where their reputations as popular heroes among the inhabitants, as well as the maze of mangrove swamps, rendered them invulnerable to capture. (58) If the Binh Xuyen pirates were the Robin Hoods of Vietnam, then the Rung Sat ("Forest of the Assassins") was their Sherwood Forest.

Their popular image was not entirely undeserved, for there is evidence that many of the early outlaws were ordinary contract laborers who had fled from the rubber plantations that sprang up on the northern edge of the Rung Sat during the rubber boom of the 1920's. Insufficient food and brutal work schedules with beatings and torture made most of the plantations little better than slave labor camps; many had an annual death rate higher than 20 percent. (59)

But the majority of those who joined the Binh Xuyen were just ordinary Cholon street

toughs, and the career of Le Van Vien ("Bay" Vien) was rather more typical. Born in

1904 on the outskirts of Cholon, Bay Vien found himself alone, uneducated and in need

of a job after an inheritance dispute cost him his birthright at age seventeen. He soon fell

under the influence of a small-time gangster who found him employment as a chauffeur

and introduced him to the leaders of the Cholon underworld. (60) As he established his

underworld reputation, Bay Vien was invited to meetings at the house of the underworld

kingpin, Duong Van Duong ("Ba" Duong), in the hamlet of Binh Xuyen (which later lent

its name to the group), just south of Cholon.

But the majority of those who joined the Binh Xuyen were just ordinary Cholon street

toughs, and the career of Le Van Vien ("Bay" Vien) was rather more typical. Born in

1904 on the outskirts of Cholon, Bay Vien found himself alone, uneducated and in need

of a job after an inheritance dispute cost him his birthright at age seventeen. He soon fell

under the influence of a small-time gangster who found him employment as a chauffeur

and introduced him to the leaders of the Cholon underworld. (60) As he established his

underworld reputation, Bay Vien was invited to meetings at the house of the underworld

kingpin, Duong Van Duong ("Ba" Duong), in the hamlet of Binh Xuyen (which later lent

its name to the group), just south of Cholon.

The early history of the Binh Xuyen was an interminable cycle of kidnapping, piracy, pursuit, and occasionally imprisonment until late in World War II, when Japanese military intelligence, the Kempeitai, began dabbling in Vietnamese politics. During 1943-1944 many individual gang leaders managed to ingratiate themselves with the Japanese army, then administering Saigon jointly with the Vichy French. Thanks to Japanese protection, many gangsters were able to come out of hiding and find legitimate employment; Ba Duong, for example, became a labor broker for the Japanese, and under their protection carried out some of Saigon's most spectacular wartime robberies. Other leaders joined Japanese-sponsored political groups, where they became involved in politics for the first time. (61) Many of the Binh Xuyen bandits had already taken a crash course in Vietnamese nationalist politics while imprisoned on Con Son (Puolo Condore) island. Finding themselves sharing cells with embittered political prisoners, they participated, out of boredom if nothing else, in their heated political debates. Bay Vien himself escaped from Con Son in early 1945, and returned to Saigon politicized and embittered toward French colonialism. (62)

On March 9, 1945, the fortunes of the Binh Xuyen improved further when the Japanese army became wary of growing anti-Fascist sentiments among their French military and civilian collaborators and launched a lightning preemptive coup. Within a few hours all French police, soldiers, and civil servants were behind bars, leaving those Vietnamese political groups favored by the Japanese free to organize openly for the first time. Some Binh Xuyen gangsters were given amnesty; others, like Bay Vien, were hired by the newly established Vietnamese government as police agents. Eager for the intelligence, money, and men the Binh Xuyen could provide, almost every political faction courted the organization vigorously. Rejecting overtures by conservatives and Trotskyites, the Binh Xuyen made a decision of considerable importance -they chose the Viet Minh as their allies.

While this decision would have been of little consequence in Tonkin or central Vietnam,

where the Communist-dominated Viet Minh was strong enough to stand alone, in Cochin

China the Binh Xuyen support was crucial. After launching an abortive revolt in 1940,

the Cochin division of the Indochina Communist party had been weakened by mass

arrests and executions.(63) When the party began rebuilding at the end of World War II it was already outstripped by more conservative nationalist groups, particularly

politico religious groups such as the Hoa Hao and Cao Dai. In August 1945 the head of

the Viet Minh in Cochin China, Tran Van Giau, convinced Bay Vien to persuade Ba

Duong and the other chiefs to align with the Viet Minh. (64) When the Viet Minh called a

mass demonstration on August 25 to celebrate their installation as the new nationalist

government, fifteen well-armed, bare-chested bandits carrying a large banner declaring

"Binh Xuyen Assassination Committee" joined the tens of thousands of demonstrators

who marched jubilantly through downtown Saigon for over nine hours. (65) For almost a

month the Viet Minh ran the city, managing its public utilities and patrolling the streets,

until late September, when arriving British and French troops took charge.

While this decision would have been of little consequence in Tonkin or central Vietnam,

where the Communist-dominated Viet Minh was strong enough to stand alone, in Cochin

China the Binh Xuyen support was crucial. After launching an abortive revolt in 1940,

the Cochin division of the Indochina Communist party had been weakened by mass

arrests and executions.(63) When the party began rebuilding at the end of World War II it was already outstripped by more conservative nationalist groups, particularly

politico religious groups such as the Hoa Hao and Cao Dai. In August 1945 the head of

the Viet Minh in Cochin China, Tran Van Giau, convinced Bay Vien to persuade Ba

Duong and the other chiefs to align with the Viet Minh. (64) When the Viet Minh called a

mass demonstration on August 25 to celebrate their installation as the new nationalist

government, fifteen well-armed, bare-chested bandits carrying a large banner declaring

"Binh Xuyen Assassination Committee" joined the tens of thousands of demonstrators

who marched jubilantly through downtown Saigon for over nine hours. (65) For almost a

month the Viet Minh ran the city, managing its public utilities and patrolling the streets,

until late September, when arriving British and French troops took charge.

World War II had come to an abrupt end on August 15, when the Japanese surrendered

to the Allies in the wake of atomic attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Allied

commanders had been preparing for a long, bloody invasion of the Japanese home

islands, and were suddenly faced with the enormous problems of disarming thousands of

Japanese troops scattered across East and Southeast Asia. On September 12 some 1,400 Indian Gurkhas and a company of French infantry under the command of British General

Douglas D. Gracey were airlifted to Saigon from Burma. Although he was under strict

orders to stay out of politics, General Gracey, an arch colonialist, intervened decisively on

the side of the French. When a Viet Minh welcoming committee paid a courtesy call he

made no effort to conceal his prejudices. "They came to see me and said 'welcome' and

all that sort of thing," he later reported. "It was an unpleasant situation and I promptly

kicked them out." (66) Ten days later the British secretly rearmed some fifteen hundred

French troops, who promptly executed a coup, reoccupying the city's main public

buildings. Backed by Japanese and Indian troops, the French cleared the Viet Minh out of

downtown Saigon and began a house-to house search for nationalist leaders. And with the

arrival of French troop ships from Marseilles several weeks later, France's reconquest of

Indochina began in earnest. (67)

World War II had come to an abrupt end on August 15, when the Japanese surrendered

to the Allies in the wake of atomic attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Allied

commanders had been preparing for a long, bloody invasion of the Japanese home

islands, and were suddenly faced with the enormous problems of disarming thousands of

Japanese troops scattered across East and Southeast Asia. On September 12 some 1,400 Indian Gurkhas and a company of French infantry under the command of British General

Douglas D. Gracey were airlifted to Saigon from Burma. Although he was under strict

orders to stay out of politics, General Gracey, an arch colonialist, intervened decisively on

the side of the French. When a Viet Minh welcoming committee paid a courtesy call he

made no effort to conceal his prejudices. "They came to see me and said 'welcome' and

all that sort of thing," he later reported. "It was an unpleasant situation and I promptly

kicked them out." (66) Ten days later the British secretly rearmed some fifteen hundred

French troops, who promptly executed a coup, reoccupying the city's main public

buildings. Backed by Japanese and Indian troops, the French cleared the Viet Minh out of

downtown Saigon and began a house-to house search for nationalist leaders. And with the

arrival of French troop ships from Marseilles several weeks later, France's reconquest of

Indochina began in earnest. (67)

Fearing further reprisals, the Viet Minh withdrew to the west of Saigon, leaving Bay Vien as military commander of Saigon-Cholon.(68) Since at that time the Binh Xuyen consisted of less than a hundred men, the Viet Minh suggested that they merge forces with the citywide nationalist youth movement, the Avant-Garde Youth. (69) After meeting with Bay Vien, one of the Avant-Garde's Saigon leaders, the future police chief Lai Van Sang, agreed that the merger made sense: his two thousand men lacked arms and money, while the wealthy Binh Xuyen lacked rank and file. (70) It was a peculiar alliance; Saigon's toughest criminals were now commanding idealistic young students and intelligentsia. As British and French troops reoccupied downtown Saigon, the Binh XuYen took up defensive positions along the southern and western edges of the city. Beginning on October 25, French thrusts into the suburbs smashed through their lines and began driving them back into the Rung Sat Swamp. (71) Ba Duong led the amphibious retreat of thousands of Binh Xuyen troops, Avant-Garde Youth, and Japanese deserters deep into the Rung Sat's watery maze. However, they left behind a network of clandestine cells known as "action committees" (formerly "assassination committees") totaling some 250 men.

While Binh Xuyen waterborne guerrillas harassed the canals, the action committees effectively provided intelligence, extorted money, and unleashed political terror. Merchants paid the action committees regular fees for a guarantee of their personal safety, while the famous casino, the Grand Monde, paid $2,600 a day as insurance that Binh Xuyen terrorists would not toss a grenade into its gaming halls. (72) These contributions, along with arms supplies, enabled the Binh Xuyen to expand their forces to seven full regiments totaling ten thousand men, the largest Viet Minh force in Cochin China. (73) In 1947, when the Viet Minh decided to launch a wave of terror against French colonists, the Binh Xuyen action committees played a major role in the bombings, knifings, and assaults that punctuated the daily life of Saigon-Cholon . (74)

But despite their important contributions to the revolutionary movement, the Binh Xuyen marriage to the Viet Minh was doomed from the very start. It was not sophisticated ideological disputes that divided them, but rather more mundane squabbling over behavior, discipline, and territory. Relations between Binh Xuyen gangs had always been managed on the principle of mutual respect for each chief's autonomous territory. In contrast, the Viet Minh were attempting to build a mass revolution based on popular participation. Confidence in the movement was a must, and the excesses of any unit commander had to be quickly punished before they could alienate the people and destroy the revolution. On the one hand the brash, impulsive bandit, on the other the disciplined party cadre-a clash was inevitable.

A confrontation came in early 1946 when accusations of murder, extortion and wanton violence against a minor Binh Xuyen chieftain forced the Viet Minh commander, Nguyen Binh, to convene a military tribunal. In the midst of the heated argument between the Binh Xuyen leader Ba Duong and Nguyen Binh, the accused grabbed the Viet Minh commander's pistol and shot himself in the head. Blaming the Viet Minh for his friend's suicide, Ba Duong began building a movement to oust Nguyen Binh, but was strafed and killed by a French aircraft a few weeks later, well before his plans had matured. (75)

Shortly after Ba Duong's death in February 1946, the Binh Xuyen held a mass rally in the heart of the Rung Sat to mourn their fallen leader and elect Bay Vien as his successor. Although Bay Vien had worked closely with the Viet Minh, he was now much more ambitious than patriotic. Bored with being king of the mangrove swamps, Bay Vien and his advisers devised three stratagems for catapulting him to greater heights: they ordered assassination committees to fix their sights on Nguyen Binh; (76) they began working with the Hoa Hao religious group to forge an anti-French, anti-Viet Minh coalition; (77) and they initiated negotiations with the French 2eme Bureau for some territory in Saigon.

The Viet Minh remained relatively tolerant of Bay Vien's machinations until March 1948, when he sent his top advisers to Saigon to negotiate a secret alliance with Captain Savani of the 2eme Bureau. (78) Concealing their knowledge of Bay Vien's betrayal, the Viet Minh invited him to attend a special convocation at their camp in the Plain of Reeds on May 19, Ho Chi Minh's birthday. Realizing that this was a trap, Bay Vien strutted into the meeting surrounded by two hundred of his toughest gangsters. But while he allowed himself the luxury of denouncing Nguyen Binh to his face, the Viet Minh were stealing the Rung Sat. Viet Minh cadres who had infiltrated the Binh Xuyen months before called a mass meeting and exposed Bay Vien's negotiations with the French. The shocked nationalistic students and youths launched a coup on May 28; Bay Vien's supporters were arrested, unreliable units were disarmed and the Rung Sat refuge was turned over to the Viet Minh. Back on the Plain of Reeds, Bay Vien sensed an ugly change of temper in the convocations, massed his bodyguards, and fled toward the Rung Sat pursued by Viet Minh troops. (79) En route he learned that his refuge was lost and changed direction, arriving on the outskirts of Saigon on June 10. Hounded by pursuing VietMinh columns, and aware that return to the Rung Sat was impossible, Bay Vien found himself on the road to Saigon.

Unwilling to join with the French openly and be labeled a collaborator, Bay Vien hid in the marshes south of Saigon for several days until 2eme Bureau agents finally located him. Bay Vien may have lost the Rung Sat, but his covert action committees remained a potent force in Saigon-Cholon and made him invaluable to the French. Captain Savani (who had been nicknamed "the Corsican bandit" by French officers) visited the Binh Xuyen leader in his hideout and argued, "Bay Vien, there's no other way out. You have only a few hours of life left if you don't sign With us." (80) The captain's logic was irrefutable; on June 16 a French staff car drove Bay Vien to Saigon, where he signed a prepared declaration denouncing the Communists as traitors and avowing his loyalty to the present emperor, Bao Dai. (81) Shortly afterward, the French government announced that it "had decided to confide the police and maintenance of order to the Binh Xuyen troops in a zone where they are used to operating" and assigned them a small piece of territory along the southern edge of Cholon (82)

In exchange for this concession, eight hundred gangsters who had rallied to Bay Vien from the Rung Sat, together with the covert action committees, assisted the French in a massive and enormously successful sweep through the twin cities in search of Viet Minh cadres, cells, and agents. As Bay Vien's chief political adviser, Lai Huu Tai, explained, "Since we had spent time in the maquis and fought there, we also knew how to organize the counter maquis. "(83)

But once the operation was finished, Bay Vien, afraid of being damned as a collaborator,

retired to his slender turf and refused to budge. The Binh Xuyen refused to set foot on

any territory not ceded to them and labeled an independent "nationalist zone." In order to

avail themselves of the Binh Xuyen's unique abilities as an urban counterintelligence and

security force, the French were obliged to turn over Saigon-Cholon block by block. By

April 1954 the Binh Xuyen military commander, Lai Van Sang, was director-general of

police, and the Binh Xuyen controlled the capital region and the sixty-mile strip between

Saigon and Cap Saint Jacques. Since the Binh Xuyen's pacification technique required

vast amounts of money to bribe thousands of informers, the French allowed them carte

blanche to plunder the city. In giving the Binh Xuyen this economic and political control

over Saigon, the French were not only eradicating the Viet Minh, but creating a political

counterweight to Vietnamese nationalist parties gaining power as a result of growing

American pressure for political and military Vietnamization. (84) By 1954 the illiterate,

bull necked Bay Vien had become the richest man in Saigon and the key to the French

presence in Cochin China. Through the Binh Xuyen, the French 2eme Bureau countered the

growing power of the nationalist parties, kept Viet Minh terrorists off the streets, and

battled the American CIA for control of South Vietnam. Since the key to the Binh

Xuyen's power was money, and quite a lot of it, their economic evolution bears

examination.

But once the operation was finished, Bay Vien, afraid of being damned as a collaborator,

retired to his slender turf and refused to budge. The Binh Xuyen refused to set foot on

any territory not ceded to them and labeled an independent "nationalist zone." In order to

avail themselves of the Binh Xuyen's unique abilities as an urban counterintelligence and

security force, the French were obliged to turn over Saigon-Cholon block by block. By

April 1954 the Binh Xuyen military commander, Lai Van Sang, was director-general of

police, and the Binh Xuyen controlled the capital region and the sixty-mile strip between

Saigon and Cap Saint Jacques. Since the Binh Xuyen's pacification technique required

vast amounts of money to bribe thousands of informers, the French allowed them carte

blanche to plunder the city. In giving the Binh Xuyen this economic and political control

over Saigon, the French were not only eradicating the Viet Minh, but creating a political

counterweight to Vietnamese nationalist parties gaining power as a result of growing

American pressure for political and military Vietnamization. (84) By 1954 the illiterate,

bull necked Bay Vien had become the richest man in Saigon and the key to the French

presence in Cochin China. Through the Binh Xuyen, the French 2eme Bureau countered the

growing power of the nationalist parties, kept Viet Minh terrorists off the streets, and

battled the American CIA for control of South Vietnam. Since the key to the Binh

Xuyen's power was money, and quite a lot of it, their economic evolution bears

examination.

The Binh Xuyen's financial hold over Saigon was similar in many respects to that of American organized crime in New York City. The Saigon gangsters used their power over the streets to collect protection money and to control the transportation industry, gambling, prostitution, and narcotics. But while American gangsters prefer to maintain a low profile, the Binh Xuyen flaunted their power: their green-bereted soldiers strutted down the streets, opium dens and gambling casinos operated openly, and a government minister actually presided at the dedication of the Hall of Mirrors, the largest brothel in Asia.

Probably the most important Binh Xuyen economic asset was the gambling and lottery

concession controlled through two sprawling casinos -the Grand Monde in Cholon and

the Cloche d'Or in Saigon-which were operated by the highest bidder for the annually

awarded franchise. the Grand Monde had been opened in 1946 at the insistence of the

governor-general of Indochina, Adm. Thierry d'Argenlieu, in order to finance the colonial

government of Cochin China. (85) The franchise was initially leased to a Macao Chinese

gambling syndicate, which made payoffs to all of Saigon's competing political forces-the

Binh Xuyen, Emperor Bao Dai, prominent cabinet ministers, and even the Viet Minh. In

early 1950 Bay Vien suggested to Capt. Antoine Savani that payments to the Viet Minh

could be ended if he were awarded the franchise. (86) The French agreed, and Bay Vien's

political adviser, Lai Huu Tai (Lai Van Sang's brother), met with Emperor Bao Dai and

promised him strong economic and political support if he agreed to support the measure.

But when Bao Dai made the proposal to President Huu and the governor of Cochin, they

refused their consent, since both of them received stipends from the Macao Chinese.

However, the Binh Xuyen broke the deadlock in their own inimitable fashion: they

advised the Chinese franchise holders that the Binh Xuyen police would no longer protect

the casinos from Viet Minh terrorists (87) kidnapped the head of the Macao syndicate,

(88) and, finally, pledged to continue everybody's stipends. After agreeing to pay the

government a $200,000 deposit and $20,000 a day, the Binh Xuyen were awarded the

franchise on December 31, 1950. (89) Despite these heavy expenses, the award of the

franchise was an enormous economic coup; shortly before the Grand Monde was shut

down by a new regime in 1955, knowledgeable French observers estimated that it was the

most profitable casino in Asia, and perhaps in the world. (90)

Probably the most important Binh Xuyen economic asset was the gambling and lottery

concession controlled through two sprawling casinos -the Grand Monde in Cholon and

the Cloche d'Or in Saigon-which were operated by the highest bidder for the annually

awarded franchise. the Grand Monde had been opened in 1946 at the insistence of the

governor-general of Indochina, Adm. Thierry d'Argenlieu, in order to finance the colonial

government of Cochin China. (85) The franchise was initially leased to a Macao Chinese

gambling syndicate, which made payoffs to all of Saigon's competing political forces-the

Binh Xuyen, Emperor Bao Dai, prominent cabinet ministers, and even the Viet Minh. In

early 1950 Bay Vien suggested to Capt. Antoine Savani that payments to the Viet Minh

could be ended if he were awarded the franchise. (86) The French agreed, and Bay Vien's

political adviser, Lai Huu Tai (Lai Van Sang's brother), met with Emperor Bao Dai and

promised him strong economic and political support if he agreed to support the measure.

But when Bao Dai made the proposal to President Huu and the governor of Cochin, they

refused their consent, since both of them received stipends from the Macao Chinese.

However, the Binh Xuyen broke the deadlock in their own inimitable fashion: they

advised the Chinese franchise holders that the Binh Xuyen police would no longer protect

the casinos from Viet Minh terrorists (87) kidnapped the head of the Macao syndicate,

(88) and, finally, pledged to continue everybody's stipends. After agreeing to pay the

government a $200,000 deposit and $20,000 a day, the Binh Xuyen were awarded the

franchise on December 31, 1950. (89) Despite these heavy expenses, the award of the

franchise was an enormous economic coup; shortly before the Grand Monde was shut

down by a new regime in 1955, knowledgeable French observers estimated that it was the

most profitable casino in Asia, and perhaps in the world. (90)