The Heart of Everything That is,The Untold Story of Red Cloud,

An American Legend

By Bob Drury & Tom Clavin

18

THE

GREAT

ESCAPE

More than any other incident

in the long and bloody history

of red-white relations,

Colonel Chivington’s

merciless attack at Sand

Creek did more to unite the

Plains tribes against the

United States. While the hills

were still echoing with the

wails of mourning mothers,

wives, and daughters,

Cheyenne runners with war

pipes were sent out to Lakota

camped on the Solomon Fork

and to Arapaho on the

Republican. War councils

were convened, and in

preparation for an

unprecedented winter

campaign the Head Men of

the three tribes selected

nearly 1,000 braves to move

on the closest Army barracks,

a contingent of infantry at

Fort Rankin on the South

Platte in the northeast corner

of Colorado. The Indians rode

in formal battle columns, the

Sioux warriors in the van. A

place of honor was reserved

for the once-pacifist Spotted

Tail.

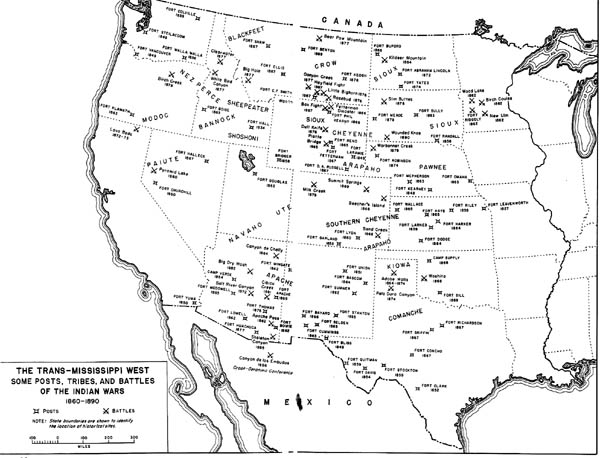

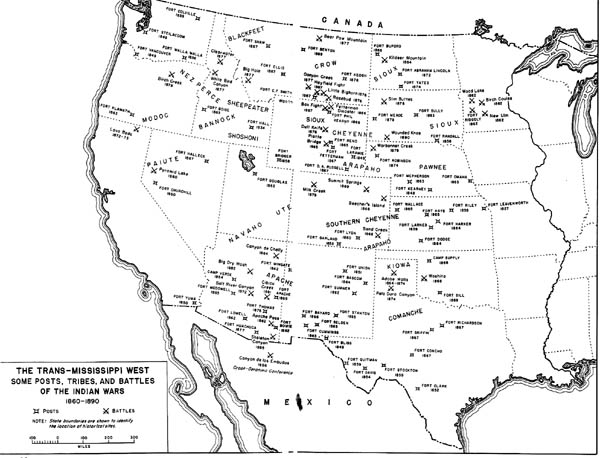

At dawn on January 7, while the main body of warriors hid behind a row of rolling sand hills south of the Army stockade, seven painted decoys descended from the snow-covered heights and paraded before the post. Predictably, a column of about fifty volunteer cavalry, strengthened by a nearly equal number of civilians from the nearby hamlet of Julesburg, poured out in pursuit. But before they could ride into the trap, some overanxious braves broke from concealment and charged. The whites recognized the ambush, turned, and fled as cannons from the fort bombarded their pursuers. They reached the post, but not before losing fourteen cavalrymen and four civilians. The enraged Head Men ordered the offending braves quirted by the akicita, the ultimate humiliation, and led the war party one mile east to plunder the now abandoned stage station and warehouses at Julesburg.

Over the next month the southern Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho cut a bloody swath through Kansas, Nebraska, and Colorado, finally circling back to again sack Julesburg, this time with the assistance of a party of northern Strong Hearts led by Crazy Horse. Again the garrison at Fort Rankin could do nothing but watch the rebuilt stock station burn. But now the Indians recognized that time was running out. Although Colonel Chivington had resigned his commission in the face of a pending court martial, Army troops from Denver, Nebraska’s Fort Kearney, and Wyoming’s Fort Laramie were already mobilizing. With certain retaliation awaiting them on three compass points, there was no other direction for the southern tribes to ride but north into the Powder River Country. No soldiers would dare follow them into the great warrior chief Red Cloud’s territory.

As they headed north the Indians looted and burned farms, ranches, and stagecoach relay stations. Precious telegraph poles, hauled to the treeless prairie and pounded into the ground four years earlier, were hacked down; their annealed wires were spooled and stolen. Supply wagons carrying food to Denver were stopped and destroyed, and the few late-starting emigrant wagon trains hoping to winter over at Fort Laramie were plundered and torched. That year the frozen carcasses of white men and women littered the “Glory Road” from eastern Nebraska to central Colorado, providing rare winter sustenance for wolves and coyotes while the citizens of Denver faced severe food shortages.

The Indian columns,

swollen with herds of

captured cattle as well as

pack horses and mules piled

with plunder, stuck to wellworn trails and buffalo fords.

Yet Major General Grenville

Dodge, the new Army

commander of the region,

was bewildered as to their

whereabouts. Dodge had

assumed responsibility for the

Oregon Trail when the War

Department, pressured by

overland stage and railroad

executives, finally recognized

that local volunteers and

militias were as much of a

hindrance to progress as the

hostiles. Dodge was a railroad

engineer by profession and a

booster of the Union Pacific,

and his primary assignment

was to clear and hold the

North Platte corridor for the

future laying of tracks toward

the Rockies. In the wake of

the attack at Julesburg, Dodge

ordered his field commander

to ride south to the

Republican to punish the

Indians. How the two forces

moving in opposite directions

across the snow-blanketed

Plains managed to miss each

other remains a puzzle. But

the cavalry’s circuitous wildgoose chase across 300 miles

of empty country left the

entire Platte River Valley

open.

The Indian columns,

swollen with herds of

captured cattle as well as

pack horses and mules piled

with plunder, stuck to wellworn trails and buffalo fords.

Yet Major General Grenville

Dodge, the new Army

commander of the region,

was bewildered as to their

whereabouts. Dodge had

assumed responsibility for the

Oregon Trail when the War

Department, pressured by

overland stage and railroad

executives, finally recognized

that local volunteers and

militias were as much of a

hindrance to progress as the

hostiles. Dodge was a railroad

engineer by profession and a

booster of the Union Pacific,

and his primary assignment

was to clear and hold the

North Platte corridor for the

future laying of tracks toward

the Rockies. In the wake of

the attack at Julesburg, Dodge

ordered his field commander

to ride south to the

Republican to punish the

Indians. How the two forces

moving in opposite directions

across the snow-blanketed

Plains managed to miss each

other remains a puzzle. But

the cavalry’s circuitous wildgoose chase across 300 miles

of empty country left the

entire Platte River Valley

open.

When a disgusted General

Dodge finally received word

that the Indians were fleeing

north, he summoned to

Wyoming an ambitious

Indian fighter, General

Patrick Connor, to finish the

job. Connor was a veteran of

the Indian wars in Texas and

California, and had secured

his reputation two years

earlier when he fell on a

Shoshone camp on the Bear

River in Utah and slaughtered

278 men, women, and

children. He would find

fighting Lakota Bad Faces

and Cheyenne Dog Soldiers

quite another matter.

When a disgusted General

Dodge finally received word

that the Indians were fleeing

north, he summoned to

Wyoming an ambitious

Indian fighter, General

Patrick Connor, to finish the

job. Connor was a veteran of

the Indian wars in Texas and

California, and had secured

his reputation two years

earlier when he fell on a

Shoshone camp on the Bear

River in Utah and slaughtered

278 men, women, and

children. He would find

fighting Lakota Bad Faces

and Cheyenne Dog Soldiers

quite another matter.

In the meantime the southern tribes crossed the frozen North Platte above Mud Springs, Nebraska, strewing shelled corn from the looted Julesburg warehouses to steady their ponies’ footing on the ice. Mud Springs was the site of a telegraph station set in a bowl-shaped dell, and the Indians robbed the lightly defended outpost of its horses and a large herd of beef cattle. Before they could cut the telegraph lines, however, an operator managed to tap out a call for help. And despite the tribes’ overwhelming numbers, the dozen or so whites firing from loopholes bored into the station’s thick adobe walls managed to hold out. Over the next twenty-four hours 170 men from the 11th Ohio Cavalry arrived from forts on either side of the boggy swale. Many were clad in their finest “Bridger buckskins” and mounted on Indian ponies.

This suited the Indians fine; they wanted a fight, anticipating even more scalps, guns, and horses to add to their growing collection. But the officer in command of the rescue party prudently sized up their strength and instead had his troopers dig rifle pits in which to wait them out. He was a frontier veteran, and had apparently learned that this was never a bad strategy with the impatient Plains tribes. Despite a hide and seek skirmish that lasted for the better part of two days and nights, the braves soon grew bored. On the second night, under cover of darkness, the caravan slipped away into Nebraska’s Sand Hills and resumed its trek north toward Red Cloud’s country.

When the Indian columns reached the Black Hills the Arapaho broke off toward the southwest while the majority of Cheyenne and Lakota circled north of the range and rode for the Powder. The exceptions were Spotted Tail and his band. The mercurial Brule, having undergone yet another change of heart, vowed never again to fight the Americans, and took his people east to the White River, beneath the Badlands, where, aside from occasional treks to Fort Laramie, he would remain for the rest of his life. The three columns had traversed more than 400 miles of bitter winter landscape, with the United States government having little idea of their whereabouts for most of the journey. They had also killed more soldiers, emigrants, teamsters, and ranchers than the number of Cheyenne murdered at Sand Creek.

The enraged General Dodge responded by ordering all-out war on any Indians, with no consideration given to the geographic boundaries offered by the Indian agent Thomas Twiss ten years earlier. Any red man was fair game, and a deep hole dug beneath hastily erected gallows just beyond Fort Laramie’s walls began to fill with corpses. In his journal the young Second Lieutenant James Regan described watching three Lakota hanged from the crude wooden structure, “in a most barbarous manner by means of coarse chains around their necks, and heavy chains and iron balls attached to the lower part of the naked limbs to keep them down. There was no drop. They were allowed to writhe and strangle to death. . . . Their lifeless bodies, swayed by every passing breeze, were permitted to dangle from the cross-piece until they rotted and dropped to the ground. We could see their bones protruding from the common grave under the gallows.”

Among those hanged and

left to decompose were a

luckless group of Laramie

Loafers who were accused of

riding on Fort Rankin with

the southern hostiles but

whose true crime may have

been skinning and barbecuing

a number of the post’s feral

cats that the quartermaster

valued as mousers and ratters.

Not long afterward two

Lakota Head Men arrived

with a white female prisoner

they had purchased from a

band of wild Cheyenne. Their

intention was to curry favor

with the whites by returning

her to her people, and they

assumed that this show of

good faith would stand them

in good stead with the

soldiers. Instead the

hysterical white woman

accused them of rape. They

were led to the scaffold by

the fort’s temporary

commander, Colonel Thomas

Moonlight, and after their

execution they hung in

artillery trace chains and leg

irons until the putrid flesh

peeled from their skeletons.

Among those hanged and

left to decompose were a

luckless group of Laramie

Loafers who were accused of

riding on Fort Rankin with

the southern hostiles but

whose true crime may have

been skinning and barbecuing

a number of the post’s feral

cats that the quartermaster

valued as mousers and ratters.

Not long afterward two

Lakota Head Men arrived

with a white female prisoner

they had purchased from a

band of wild Cheyenne. Their

intention was to curry favor

with the whites by returning

her to her people, and they

assumed that this show of

good faith would stand them

in good stead with the

soldiers. Instead the

hysterical white woman

accused them of rape. They

were led to the scaffold by

the fort’s temporary

commander, Colonel Thomas

Moonlight, and after their

execution they hung in

artillery trace chains and leg

irons until the putrid flesh

peeled from their skeletons.

The great group of southern hostiles finally reached the Upper Powder in March 1865. Prior to their arrival the Bad Faces had passed an uneventful season; the highlight, as recorded by the Winter Count, was the capture and killing of four Crows attempting to steal horses. Now came this great group of fugitives trailing large herds of stolen cattle and pack horses and travois piled high with looted sacks of flour, cornmeal, rice, sugar, and more. The northerners gathered goggle eyed around strange bolts of multicolored cloth, and more than a few became nauseated after feasting on a mixture of tinned oysters, ketchup, and candied fruit. But most alluring were the repeating rifles and ammunition taken from the torched ranches and mail stations. Red Cloud’s warriors and most other fighters and hunters on the Upper Powder still relied primarily on bows and arrows, and the rush to trade for these new, prized weapons was loud and raucous.

It was initially a hesitant reunion, however, despite the air of excitement. There were many northern Oglalas, not least among them Red Cloud, who remembered well the insults that had fired the decades-long feud between the Smoke People and the Bear People. And though the Cheyenne had no such divisions, the years apart had exacerbated cultural differences between the northern and southern branches. The Northern Cheyenne, clad in rough buffalo robes and with red painted buckskin strips plaited through crow feathers entwined in their hair, barely recognized their southern cousins, who wore cloth leggings and wool serapes. The two branches even had some trouble communicating, as the Northern Cheyenne had adopted many words from the Sioux dialect. In the end, however, turning away the ragged widows and bewildered orphans of Sand Creek would have been unthinkable. Soon enough their dramatic stories set the Bad Faces’ blood boiling. The southerners described the outrage at Sand Creek in all its wretched detail, and told of the persecution of the docile Loafers as well as the hanging of the Lakota Head Men. Crazy Horse in particular was reported to have reacted to these tales of betrayal and brutality with an unconcealed rage for blood vengeance.

The more circumspect Red Cloud also recognized that the white man’s war had finally arrived on his doorstep, first from the east following the troubles in Minnesota, and now from the south. There was nowhere to run. Nor, he reasoned, should his people have to run. It was time, once and for all, to fight the mighty United States and expel the Americans from the High Plains. He had long planned how to do this. The only question had been when. Sand Creek had answered that: Now.

In the early spring of 1865, not long after the southern tribes reached the Powder River Country, the leaders of the Sioux and Cheyenne soldier societies convened a war council on the Tongue. With over 2,000 braves at their disposal, Lakota war chiefs such as Red Cloud, Hump, and Young-Man Afraid-Of-His-Horses plotted strategy with an assortment of Cheyenne counterparts including the regal Dull Knife 1 and the ferocious Roman Nose, who had lost kinsmen at Sand Creek. Although each tribe kept its own laws and customs, all were gradually coming to think of themselves as “The People.” They had the Americans to thank for that.

1. It is a measure of the integration between the Northern Cheyenne and the northern Lakota that this Cheyenne chief, named Morning Star in his own language, was by now almost universally known by his Sioux name, Dull Knife.

Red Cloud was the first to address the gathering. “The Great Spirit raised both the white man and the Indian, ” he told his fellow fighters. “I think he raised the Indian first. He raised me in this land and it belongs to me. The white man was raised over the great waters, and his land is over there. Since they crossed the sea, I have given them room. There are now white people all about me. I have but a small spot of land left. The Great Spirit told me to keep it.”

No more eloquent statement of purpose was required. For once the squabbling bands and tribes were in agreement, and it was decided that after the early summer buffalo hunt—which would prove a particularly cumbersome affair, given the number of mouths to feed— the main force of the coalition would strike the whites at the last crossing of the North Platte on the trails west. This was the Bridge Station outpost, about 130 miles upstream from Fort Laramie. In the meantime, smaller groups of raiders who could be spared from the hunt were sent west, south, and east to keep the soldiers protecting the “Glory Road” and the South Pass of the Rockies off balance, while also gathering intelligence regarding the Army’s movements.

It was a sound plan that leaped to a rousing start in April when a war party of Dog Soldiers burned out a key stage relay station west of Fort Laramie on the Wind River. The Indians killed all five of the station’s defenders and staked their mutilated corpses on trees. A large detachment of cavalry under Fort Laramie’s gallows happy temporary commander, Colonel Moonlight, rode out to hunt the Indians down. But as in the Army’s ineffectual response to Julesburg, Moonlight’s patrol wandered in circles over 450 miles of Wind River country without seeing a hostile. Meanwhile the offending Dog Soldiers had moved east and were raiding the outpost at Deer Creek along the North Platte in conjunction with Lakota riding with Young-Man-Afraid-Of-His-Horses. Through May and June they attacked Wyoming stage stations, emigrant wagon trains, and small Army patrols, scalping and burning from Dry Creek to Sage Creek. On one humiliating occasion a platoon dispatched to chase down raiders returned to Fort Laramie at dusk and reported no Indians within twenty-five miles of the post. They had no sooner unsaddled their horses on the parade ground than a band of about thirty Lakota galloped into the fort, shooting, yelling, and waving buffalo robes. They stampeded the Army mounts through the open gates. They were never caught.

The brazen raids led General Dodge back in Omaha to again vent his spleen on the Laramie Loafers. There were at least 1,500 and probably closer to 2,000 docile Indians living within ten miles of the fort, and in June the general ordered his new field commander, the California General Patrick Connor, to wipe them out. Connor quite sensibly replied that these people were “friendlies, ” and reminded Dodge that if they had not risen after the atrocities on the gallows, he doubted they ever would. Further, he said, if the United States was intent on turning every Indian on the Plains against the whites, a massacre of the Loafers would be a fine start. Dodge blinked. After consulting with the War Department he telegraphed Connor to instead round up the Loafers and transport them southeast to Fort Kearney, where they would ostensibly be taught to farm. Fort Kearney was on the Lower Platte, deep in southern Nebraska: Pawnee country. The Loafers were indeed manageable, but they were not eager to be shipped into the heart of their ancient enemy’s territory.

Nonetheless the Loafers were escorted under armed guard from Fort Laramie in early June, and as they passed the site of the Brule village where Lieutenant Grattan had met his end eleven years earlier, the ghosts seemed to stir them. A few nights later Crazy Horse slipped into their camp and discovered that they were already plotting an escape. He buoyed their spirits when he informed them that a war party of Strong Hearts was lurking just behind the low hills across the North Platte. The next morning, under the pretense of letting their herd graze, the Loafers lured their Army escort into an ambush. Five soldiers, including the officer in charge of the detail, were killed on the very spot where, fourteen years earlier, the Horse Creek Treaty to end all red-white hostilities had been signed. Seven more were wounded. The only Indian casualty was a Sioux prisoner, executed while still in chains.

The newly militant Indians then swam the river with their ponies as the Strong Hearts formed a defensive shield. They rode north. The next day they were pursued by Colonel Moonlight leading a contingent of 235 Ohio, Kansas, and California cavalrymen from Fort Laramie. By the time the hard-riding American force reached Dead Man’s Fork, a small creek flowing into the White River near the Nebraska–South Dakota border, more than a third of the troopers had been forced to turn back after their big American steeds gave out crossing the waterless, hardscrabble tract. The fugitive Loafers and the Strong Hearts had counted on this. They hid themselves amid the thick sage and chokecherries that lined the stream’s steep banks. When what was left of the troop dismounted to water the herd, the Indians sprang. They stampeded and captured the entire remuda, leaving Moonlight and his company to walk back to Fort Laramie over 120 miles of trackless prairie. Moonlight vowed never again to enter hostile territory without proper pickets and hobbles for his mounts, even if it meant disobeying orders. He needn’t have worried. On reaching Fort Laramie, the colonel was relieved of command by General Connor, who cited his incompetence, and shortly thereafter Moonlight was mustered out of the service by General Dodge.

The Army had no idea when, where, or how the hostiles would strike next. But old frontier hands like Jim Bridger assured the officers that it was a long held Indian custom to celebrate even the most minor victories with weeks of feasts and scalp dances. There was time, he said, to amass and mount a large enough force to ride out and surprise them. With this, a degree of complacency settled over the forts and camps along the Oregon Trail. But for once the mountain man was mistaken because Red Cloud was yet again one step ahead of his enemies.

For most of that summer the station had been manned by a feuding mix of Kansas and Ohio men, among them twenty-year-old Lieutenant Caspar Collins of the 11th Ohio Cavalry. As a child Collins had dreamed of fighting Indians, and when he came west in 1862 he was impatient for the opportunity. But after three years on the prairie his natural curiosity had tempered his bloodlust, and he had been known to ride off by himself along the Upper Powder, camping with friendly Oglalas and Brules. There were even reports that in less troubled times Crazy Horse himself had taught Collins bits of the Lakota language as well as how to fashion a bow and arrows. By all accounts Collins was an affable and capable junior officer, with a sterling reputation among the enlisted men. In July, when a large company of Kansas cavalry arrived at Bridge Station, he was bemused more than anything else. “I never saw so many men so anxious in my life to have a fight with the Indians, ” Collins wrote in a letter home. “But ponies are faster than American horses, and I think they will be disappointed.”

Collins’s reflections aside, there was bad blood between his Ohioans and the rough Jayhawkers, and not long after Collins was dispatched to Fort Laramie to secure fresh mounts, the commander of the new Kansas contingent banished most of the Ohio troops to a more isolated post farther west on the Sweetwater. Collins knew nothing of this development as he waited at Fort Laramie to join a patrol riding back to Bridge Station, and it was his bad luck to have still been there when General Dodge’s new field commander General Connor arrived. Connor was yet another of the Army’s hot-tempered Irishmen—he had been born in County Kerry—and in addition to his temper he possessed a constitution as hardy as a Connemara pony’s. He was soon to acquire the Indian nickname “Red Beard” for the ornate copper sideburns that set off his lupine eyes set deep in a face as pinched as a hatchet blade. Connor spotted Collins apparently idling on the parade ground one day, and he tore into the young lieutenant before several witnesses.

“Why have you not returned to your post?”

Collins attempted to explain. The general cut him off.

“Are you a coward?”

Collins was shaken. “No, sir.”

“Then report to your command without further delay.”

Collins rode out the next day. Connor’s rebuke may have been ringing in his ears when Collins reached Bridge Station on the afternoon of July 25 to find only a skeleton squad of his Ohio company still remaining. It was the very day Red Cloud had chosen to attack. The war chief’s tactics were the same as the plan that had nearly worked for the southern tribes at Fort Rankin, near Julesburg. Earlier that morning, before Collins’s arrival, the main body of Cheyenne and Lakota— which included Oglala, Brule, Miniconjou, Sans Arcs, and Blackfoot Sioux warriors— had concealed themselves behind the red sandstone buttes on the north side of the river. But, taking a lesson from the botched ambush at Fort Rankin, Red Cloud had raised a police force from Crazy Horse’s Strong Hearts as insurance in case his excitable braves tried to break cover too early. The Cheyenne recruited members of their own Crazy Dog Society to do the same. Red Cloud then sent a dozen or so riders in full battle regalia out into the little valley fronting the station, hoping to draw out most of its 119 defenders.

At first a howitzer battery seemed to have taken the bait, but after crossing the bridge the cannoneers moved no farther, opting to dig in on the north bank of the river and merely lob shells into the hills. Red Cloud was restless but waited until the tangerine twilight turned to charcoal dusk before signaling for the decoys to return. That night he altered his plan and selected a small party of Bad Faces to creep into the culvert beneath the north side of the bridge and hide themselves amid the brush and thick willows. At dawn he again deployed his baiting riders, who this morning cantered even closer to the fort and taunted the soldiers by shouting obscenities, in English, that they had learned from traders.

Again the ploy looked to have worked. The gates opened and at the head of a column of cavalry rode Lieutenant Collins. Red Cloud had no idea that the horsemen were coming out not to fight the decoys, but to escort into Bridge Station five Army freight wagons returning from delivering supplies to the Ohioans on the Sweetwater. By this time even the rawest recruit on the frontier was aware of the Indians’ repeated use of a handful of braves to lay a trap. Collins had also been warned. Earlier that morning, as he donned the new dress uniform that he had purchased at Fort Laramie, several of his remaining Ohioans had tried to dissuade him from riding out with only twenty-eight men. When he persisted they implored him to at least request from the Kansan commander a larger detail. Again Collins said no, and at this a fellow officer from his regiment handed him his own weapons, a brace of Navy Colts. Collins stuck one into each boot, selected a high-strung gray from the stable, and mounted up at 7:30. Before departing he handed his cap to his Ohio friend “to remember him by.”

The decoys scattered as Collins and his troop crossed the bridge, followed on foot by the Ohio men and a few Kansans with Spencer carbines, eleven soldiers in all, acting as a volunteer rear guard. They watched from the riverbank as the riders moved half a mile into the North Platte Valley. The hills then erupted with painted warhorses, pinging arrows, and glinting steel. The Lakota swept down from the northern buttes, and the Cheyenne rode in from the west. On Collins’s orders the little column wheeled into two ranks and discharged a volley from their carbines. A bitter-tasting fog of smoke rolled toward the river. Then Collins flinched and nearly toppled from his horse. He had been shot in the hip, and a scarlet stain seeped through his pants leg. By the time he regained his balance there were so many Indians swarming his column that lookouts on the Bridge Station parapets lost sight of the Bluecoats in the swirling dust. Except for one. Lieutenant Caspar Collins, an arrow buried deep in his forehead, was clearly visible for a moment before he and his horse disappeared into a scrum of charging braves.

Indian and American horseflesh continued to collide at close quarters, the Indians slashing with knives and spears and swinging tomahawks and war clubs to avoid firing into their own lines. The unwieldy carbines were now useless, and cavalrymen fought back with revolvers. A galloping horse broke out of the smoky haze with a wounded trooper hunched over its neck, making for the bridge. Another followed. Then another. The rear guard opened up with the Spencers, firing wildly into the melee. As if by magic the Bad Faces hidden beneath the span appeared. They threw their bodies in front of the retreating horsemen. The rear guard charged them, desperate to keep the escape route open. Riderless horses and single riders with arrows protruding from all parts of their bodies galloped back through the pandemonium. A cannon boomed from the Bridge Station bastions, and soldiers on the catwalks watched an Indian drive his spear through the heart of a dismounted cavalryman, yank it out, turn, and lunge at another, piercing his chest. But the second soldier was not dead. He fell forward, pressed his revolver against his assailant’s head, and with his last cartridge blew out the Indian’s brains.

Thirty minutes into the fight Red Cloud signaled the Cheyenne chief Roman Nose to break off his Dog Soldiers. They thundered up the valley toward the approaching freight wagon train. The train’s five lead scouts, cresting a rise in the road that put them in sight of the fort, saw a horde of 500 Indians bearing down on them. The scouts galloped for the river and splashed their mounts into the current. Three made it across. The men at the bridge who had formed the rear guard, including the lieutenant who had given Collins his revolvers, retreated to the stockade. The lieutenant volunteered to lead a rescue detachment, reminding the post commander that the twenty wagoneers were also men from the 11th Ohio Cavalry. The Kansan refused, insisting that he needed every available body to defend the fort. The lieutenant punched him in the face, was subdued, and was taken to the guardhouse at about the time Roman Nose descended on the freighters, just reaching the same ridgeline as the scouts.

Americans dropped one by one over the succeeding four hours; but the Indians’ arrows and muskets were no match for the soldiers’ breech-fed, seven-shot Spencer carbines, and the survivors managed to hold off their circling attackers. By mid-afternoon the Indians decided to take a new tack, slithering closer on all sides through shallow trenches they scraped out of the sandy soil with knives and tomahawks, rolling logs and large boulders before them. The besieged troop, holed up below the road, could not see them. But the men on the fourteen-foot walls of Bridge Station did. They fired howitzer shells as a warning, but the meaning of the signal was lost on the teamsters. By four o’clock the Indians had crawled to within yards of the makeshift stockade. All went quiet; then came a shrill shriek. The Indians rose by the hundreds, “seeming to spring from the very ground, ” according to one historian. A fire broke out and soldiers on the Bridge Station walls could hear screams but could see nothing through the thick black smoke. The Indians were burning both men and wagons.

Night fell and the Lakota and Cheyenne returned to the hills while the post commander at Bridge Station counted twenty-eight men missing and presumed dead, twice as many wounded, and perhaps half left to fight. The telegraph lines east of the fort had been cut, and at ten o’clock a half-blood scout mounted a captured Indian pony and slipped through a side gate with instructions to ride for Deer Creek Station twenty-eight miles to the east. From there word could be transmitted to General Connor at Fort Laramie. The scout made it through.

On the far side of the red bluffs the day ended just as inconclusively for Red Cloud. There is no record of his losses, but the Army estimated that sixty Indians had fallen. Though this number was probably inflated, it was still a significant toll. Moreover, not only had the Native force failed to take the outpost, but a good number of Collins’s cavalry had managed to make their way back through the Bad Faces and across the bridge to safety. The Cheyenne Dog Soldiers blamed the Lakota, a few even insinuating that the Lakota were cowards. The Lakota moved for their weapons but were held back at the last moment by the frustrated Red Cloud’s authority.

Red Cloud and Roman Nose spent the night repairing the damaged alliance, and the next morning the great war party paraded before Bridge Station just beyond cannon range, then swung back into the hills and vanished. Red Cloud recognized that despite his superior numbers, most of his fighters, his Oglalas and Brules in particular, were far too inexperienced, ill disciplined, and uncomprehending of tactics to lay siege to the Army outpost. Even more disturbing was the way the tribes had nearly turned on each other. The best he could hope for was that as the war progressed his followers would learn. He was probably asking too much.

General Ulysses S. Grant, the Army’s commander in chief, had long planned such a moment. The previous November, the day after the Sand Creek massacre, Grant summoned Major General John Pope to his Virginia headquarters to put such plans in motion. Despite his relative youth, the forty three-year-old Pope was an old-school West Pointer and a topographical engineer surveyor whose star had risen with several early successes on western fronts in the Civil War. It had dimmed just as rapidly when Lincoln placed him in command of the eastern forces; Pope was thoroughly outfoxed by Stonewall Jackson and James Longstreet at the Second Battle of Bull Run. Pope had been effectively exiled to St. Paul, Minnesota, until Grant recalled him to consolidate under one command a confusing array of bureaucratic Army “departments” and “districts” west of St. Louis. Grant named Pope the commanding general of a new Division of the Missouri, into which he enfolded three fractious geographic departments: Northwest, Missouri, and Kansas. This new division was also enlarged to include Utah and parts of the Dakotas. Pope’s mandate was to execute an offensive in the summer of 1865 that would, among its prime objectives, make safe the trail stamped out by John Bozeman.

The new route went by many names: the Bozeman Trail, the Montana Road, the Bozeman Cutoff. But whatever it was called, it was the road to gold in Montana. It broke north from the great Oregon Trail and shortened the journey to the new gold fields in the rugged mountains of western Montana by some 400 weary, plodding miles. Pope had appointed General Dodge as his chief subordinate, and together the two decided on a campaign plan to crush the High Plains tribes with a large-scale pincer movement. General Connor’s forces would march north out of Fort Laramie to face Red Cloud, while General Sully would lead a column northwest from Sioux City to finally finish off Sitting Bull, with whom his cavalry had been skirmishing for the better part of two years.

The optimum time for such an assault was early spring, before the lush summer prairie grasses allowed the Indian ponies to regain their speed and stamina. But even with the cessation of fighting in the East, troop movements remained a cumbersome operation, and as a result through much of the spring of 1865 General Connor commanded less than 1,000 soldiers to protect the Platte corridor. This had reduced him to dispatching what were in essence rapid reaction teams up and down the “Glory Road.” Their rapidity, however, was somewhat in question. As Red Cloud had predicted, Connor’s soldiers spent the first half of 1865 chasing ghosts.

The reports of these futile and frustrating excursions before and after the debacle at Bridge Station still festered within the Army high command when additional troops were finally assigned to the new Division of the Missouri in midsummer. General Connor’s gratitude was short-lived. The majority of the volunteers ordered into Indian Country from Civil War battlefields felt as if they had fulfilled their duty to the Union, and marched west with something less than zealous fervor in hopes that their discharge papers would outpace them. Many of those hopes were realized, and nearly half of the 4,500 reinforcements never crossed the Missouri. Connor may have wished the same for the rest. One regiment of 600 Kansas cavalry rode into Fort Laramie and promptly mutinied, refusing to ride any farther. Connor was forced to train his artillery on their camp to bring them under control. Still, he was confident that the 2,500 additional men he had received—including the Kansas mutineers—were more than enough to merge with Sully and defeat Red Cloud, Sitting Bull, and whatever allies had been foolish enough to join them. In June 1865, he issued his infamous order to subordinate officers: find the hostile tribes and kill all the males over the age of twelve.

The strategy faltered from the start. Rivers and streams still swollen from heavy spring rains delayed Sully’s Missouri crossing for weeks, and when he finally managed to ferry his 1,200 troopers across the river they rode futilely up and down its banks and tributaries for nearly a month without finding Sitting Bull. Not finding Indians was becoming habitual for the Army across the frontier. Sully’s force of eighteen cavalry companies and four infantry companies was finally pulled back to Minnesota when the War Department overreacted to a raid by a small party of Dakota Sioux near Mankato. By the time Sully arrived to wipe out the “hive of hostile Sioux, ” the Dakotas had slipped across the border into Canada. But he and his men were ordered to remain in the state in case the Indians returned. At faraway Fort Laramie, Connor was forced to readjust on the run. He decided that three prongs would replace the pincers.

To that end, in early July he ordered a column of nearly 1,400 Michigan volunteers under the command of Colonel Nelson Cole to ride north out of Omaha, skirt the east face of the Black Hills until they reached the Tongue, and wipe out a contingent of the fugitive Laramie Loafers reported to be congregating near Bear Butte. Cole was then to follow the river southwest until he met and united with the regiment of Kansas cavalry dispatched from Fort Laramie. This combined troop would then provide a flanking screen against Red Cloud’s multi tribal forces, which Connor was confident he would locate near their favorite hunting grounds on the Upper Powder. Connor himself, meanwhile, would ride at the head of 1,000 men up John Bozeman’s trail, and all three American columns were to converge on Rosebud Creek, the heart of Red Cloud’s territory.

It was as fine a tactical advance as was ever drawn up in a West Point classroom. Needless to say, it failed utterly. The sulky Kansans’ movement proved so desultory as to be almost worthless, and once again the grain-fed Army mounts in Cole’s command withered and broke down on the desiccated South Dakota prairie. As von Clausewitz had noted, “Everything in war is very simple, but the simplest thing is difficult.” Somewhere Colonel Moonlight must have felt vindicated.

Connor, freighting supplies for all three columns, remained oblivious of the difficulties his two flanking forces were experiencing when, several weeks into his own march, his Pawnee and Winnebago scouts discovered fresh tracks made by a large party of Indians moving northeast. He should have trusted his instincts; the main body of Sioux and Cheyenne were in fact still camped on the Upper Powder, hunting buffalo and celebrating the victory at Bridge Station. Instead he heeded his guides and turned his column. But the trail the Pawnee had cut belonged to a band of peaceful northern Arapaho led by a Head Man named Black Bear. Connor fell on them in north-central Wyoming near the Montana border. He raked Black Bear’s camp with his howitzers before charging, killing over sixty. The Arapaho, however, surprised him by putting up a spirited defense—their women fighting as hard as their men —before vanishing into a honeycomb of red rock canyons. A few warriors, attempting to divert the Americans, led them in the opposite direction up a shallow stream called Wolf Creek. Among the pursuing soldiers was a scout clad in buckskins whom several of the Indians recognized. They had once trapped and traded with him, and they considered him a friend. “Blanket” was his Arapaho nickname —“Blanket Jim Bridger.”

Although Connor captured a third of the large Arapaho remuda and set torches to the Arapaho camp—elk-skin lodges, buffalo robes, blankets, and an entire winter food supply of thirty tons of pemmican were devoured in the huge bonfire—it is difficult to call the “Battle of Tongue River” a victory. Black Bear’s son was killed in the artillery bombardment, and his death hardened the tribe’s enmity toward the whites. First Left Hand at Sand Creek; now Black Bear. The Army was increasing Red Cloud’s coalition for him.

Although three columns of infantry and cavalry were snaking to and fro across the High Plains searching for him —albeit reluctantly in some cases—Red Cloud appeared to have no idea that he was the object of such lusty attention. He spent his days at leisure, and whiled away long nights attending formal medicine ceremonies, feasts, and scalp dances where he, Young-Man-Afraid-Of-His-Horses, and Roman Nose were accorded places of honor. In an attempt to consolidate a popular tribal front he sent Bad Face emissaries down the Powder to take part in Sitting Bull’s large Sun Dance on the Little Missouri. But the Hunkpapa chief failed to reciprocate, and this rather stunning insult was the beginning of a lifelong rift between Red Cloud and Sitting Bull.

Toward mid-August a Lakota hunting party spotted a civilian train of about twenty wagons escorted by two companies of infantry traveling west near the Badlands. Red Cloud and Dull Knife roused 500 warriors to ride out against the party. Some of the braves wore bloodied blue uniform tunics taken during the fight at Bridge Station, and at least one carried an Army bugle captured from Caspar Collins’s command. On reaching the Bluecoats they cut off and killed one of the train’s scouts, and at first sight of the Indians the wagons were rolled into an interlocking circle, destined to become a classic Hollywood trope. The Indians spread out on two flanking mesas, taking potshots, blowing their bugle, whooping, and taunting. The enclosed soldiers responded with howitzer fire that fell harmlessly, only gouging chunks from the surrounding hills.

Soon a white flag went up; the whites wanted to parley. Red Cloud and Dull Knife personally rode out to meet with the expedition’s two leaders. The civilian wagon master—an Iowa merchant who was surreptitiously surveying a trail into Montana—was joined by an Army captain commanding the infantry companies of “galvanized Yankees”— former Confederate prisoners of war who had sworn an oath of allegiance to the Union in exchange for their release. These southerners had not expected to be pressed into frontier service, and the Union officer was probably not certain whom he could trust less, the Lakota or his own troops.

Incredibly, after much palaver the two chiefs promised the train safe passage on the condition that it strike north of the Powder River buffalo grounds as well as cede a wagonload of sugar, coffee, flour, and tobacco as a toll. If this seems a curious decision for warriors who only weeks earlier had vowed to drive all whites from their territory, the explanation lay in the fact that the red man and white man did not adhere to the same concept of warfare, much less the same rules. The Sioux and Cheyenne viewed the Americans as merely a more numerous, better-armed version of the Crows, Shoshones, or Pawnee. To the Indians there was a time for battle, and a time to celebrate or mourn the results. Unlike invading soldiers, a trespassing emigrant train, even one escorted by cavalry, was more of a nuisance than a provocation.

This mind-set would eventually change, not least under Red Cloud’s leadership. But that was yet to come. To the Indians the skirmish at Bridge Station had been a flawed victory, but a victory nonetheless, and Sand Creek had been avenged. Now it was natural to fall back, plan for the autumn buffalo hunt, and settle into winter camps to await next year’s fighting season. There was even a notion that the lesson of Bridge Station might induce the whites to abandon the Powder River Country altogether.

As far-fetched as this seems in hindsight, war as an all-encompassing endeavor, was as alien to the Indians as a naval blockade or a siege of Washington would have been. Although a few Lakota in closer contact with the whites were dimly aware of how much carnage the Americans had inflicted on each other at Chancellorsville, at Chickamauga, at Gettysburg, most had no grasp of the white man’s concept of battle as a year-round industry or as what is now called a zero sum contest. That they had not learned from Chivington’s winter ride on Sand Creek demonstrated just how ingrained was Indian custom.

As it happened, though Connor may have possessed Chivington’s ardor, he had little of the Fighting Parson’s luck. After multiple delays his two flanking columns finally met, nearly by accident, northwest of the Black Hills on the Belle Fourche, almost 100 miles away from their planned juncture on the Tongue. Unknowingly, Cole proceeded to march his 2,000 men directly between Sitting Bull’s Hunkpapa village on the Little Missouri and the Lakota-Cheyenne contingent camped on the Powder. Days of similar peregrinations followed. Cole sent out riders to find Connor’s column. They returned exhausted and bewildered. Connor dispatched his scouts to find Cole. They could not. The Americans were, in effect, lost in the wilderness; they were running low on supplies; and a grumbling Kansas contingent was ready to desert at any moment. This is how Sitting Bull and his braves found them.

next

BURN THE BODIES; EAT THE HORSES

At dawn on January 7, while the main body of warriors hid behind a row of rolling sand hills south of the Army stockade, seven painted decoys descended from the snow-covered heights and paraded before the post. Predictably, a column of about fifty volunteer cavalry, strengthened by a nearly equal number of civilians from the nearby hamlet of Julesburg, poured out in pursuit. But before they could ride into the trap, some overanxious braves broke from concealment and charged. The whites recognized the ambush, turned, and fled as cannons from the fort bombarded their pursuers. They reached the post, but not before losing fourteen cavalrymen and four civilians. The enraged Head Men ordered the offending braves quirted by the akicita, the ultimate humiliation, and led the war party one mile east to plunder the now abandoned stage station and warehouses at Julesburg.

Over the next month the southern Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho cut a bloody swath through Kansas, Nebraska, and Colorado, finally circling back to again sack Julesburg, this time with the assistance of a party of northern Strong Hearts led by Crazy Horse. Again the garrison at Fort Rankin could do nothing but watch the rebuilt stock station burn. But now the Indians recognized that time was running out. Although Colonel Chivington had resigned his commission in the face of a pending court martial, Army troops from Denver, Nebraska’s Fort Kearney, and Wyoming’s Fort Laramie were already mobilizing. With certain retaliation awaiting them on three compass points, there was no other direction for the southern tribes to ride but north into the Powder River Country. No soldiers would dare follow them into the great warrior chief Red Cloud’s territory.

⏳ ⏳ ⏳

One would expect that a

plodding diaspora of nearly

4,000 Indian men, women,

and children freighted with

nearly 900 lodges and hauling

tons of provisions and

equipment through a Plains

winter would be easy to

locate. Amazingly, no. In

moving through the densely

patrolled Platte River Valley,

the combined tribal force—

riding in three loose parallel

columns, with scouts fanned

out to the front and on either

side—crossed the South

Platte above Julesburg

without incident. A few

travelers reported spotting

thousands of distant

campfires, or hearing the beat

of war drums for miles. Yet

the Army could not find

them.As they headed north the Indians looted and burned farms, ranches, and stagecoach relay stations. Precious telegraph poles, hauled to the treeless prairie and pounded into the ground four years earlier, were hacked down; their annealed wires were spooled and stolen. Supply wagons carrying food to Denver were stopped and destroyed, and the few late-starting emigrant wagon trains hoping to winter over at Fort Laramie were plundered and torched. That year the frozen carcasses of white men and women littered the “Glory Road” from eastern Nebraska to central Colorado, providing rare winter sustenance for wolves and coyotes while the citizens of Denver faced severe food shortages.

In the meantime the southern tribes crossed the frozen North Platte above Mud Springs, Nebraska, strewing shelled corn from the looted Julesburg warehouses to steady their ponies’ footing on the ice. Mud Springs was the site of a telegraph station set in a bowl-shaped dell, and the Indians robbed the lightly defended outpost of its horses and a large herd of beef cattle. Before they could cut the telegraph lines, however, an operator managed to tap out a call for help. And despite the tribes’ overwhelming numbers, the dozen or so whites firing from loopholes bored into the station’s thick adobe walls managed to hold out. Over the next twenty-four hours 170 men from the 11th Ohio Cavalry arrived from forts on either side of the boggy swale. Many were clad in their finest “Bridger buckskins” and mounted on Indian ponies.

This suited the Indians fine; they wanted a fight, anticipating even more scalps, guns, and horses to add to their growing collection. But the officer in command of the rescue party prudently sized up their strength and instead had his troopers dig rifle pits in which to wait them out. He was a frontier veteran, and had apparently learned that this was never a bad strategy with the impatient Plains tribes. Despite a hide and seek skirmish that lasted for the better part of two days and nights, the braves soon grew bored. On the second night, under cover of darkness, the caravan slipped away into Nebraska’s Sand Hills and resumed its trek north toward Red Cloud’s country.

When the Indian columns reached the Black Hills the Arapaho broke off toward the southwest while the majority of Cheyenne and Lakota circled north of the range and rode for the Powder. The exceptions were Spotted Tail and his band. The mercurial Brule, having undergone yet another change of heart, vowed never again to fight the Americans, and took his people east to the White River, beneath the Badlands, where, aside from occasional treks to Fort Laramie, he would remain for the rest of his life. The three columns had traversed more than 400 miles of bitter winter landscape, with the United States government having little idea of their whereabouts for most of the journey. They had also killed more soldiers, emigrants, teamsters, and ranchers than the number of Cheyenne murdered at Sand Creek.

The enraged General Dodge responded by ordering all-out war on any Indians, with no consideration given to the geographic boundaries offered by the Indian agent Thomas Twiss ten years earlier. Any red man was fair game, and a deep hole dug beneath hastily erected gallows just beyond Fort Laramie’s walls began to fill with corpses. In his journal the young Second Lieutenant James Regan described watching three Lakota hanged from the crude wooden structure, “in a most barbarous manner by means of coarse chains around their necks, and heavy chains and iron balls attached to the lower part of the naked limbs to keep them down. There was no drop. They were allowed to writhe and strangle to death. . . . Their lifeless bodies, swayed by every passing breeze, were permitted to dangle from the cross-piece until they rotted and dropped to the ground. We could see their bones protruding from the common grave under the gallows.”

The great group of southern hostiles finally reached the Upper Powder in March 1865. Prior to their arrival the Bad Faces had passed an uneventful season; the highlight, as recorded by the Winter Count, was the capture and killing of four Crows attempting to steal horses. Now came this great group of fugitives trailing large herds of stolen cattle and pack horses and travois piled high with looted sacks of flour, cornmeal, rice, sugar, and more. The northerners gathered goggle eyed around strange bolts of multicolored cloth, and more than a few became nauseated after feasting on a mixture of tinned oysters, ketchup, and candied fruit. But most alluring were the repeating rifles and ammunition taken from the torched ranches and mail stations. Red Cloud’s warriors and most other fighters and hunters on the Upper Powder still relied primarily on bows and arrows, and the rush to trade for these new, prized weapons was loud and raucous.

It was initially a hesitant reunion, however, despite the air of excitement. There were many northern Oglalas, not least among them Red Cloud, who remembered well the insults that had fired the decades-long feud between the Smoke People and the Bear People. And though the Cheyenne had no such divisions, the years apart had exacerbated cultural differences between the northern and southern branches. The Northern Cheyenne, clad in rough buffalo robes and with red painted buckskin strips plaited through crow feathers entwined in their hair, barely recognized their southern cousins, who wore cloth leggings and wool serapes. The two branches even had some trouble communicating, as the Northern Cheyenne had adopted many words from the Sioux dialect. In the end, however, turning away the ragged widows and bewildered orphans of Sand Creek would have been unthinkable. Soon enough their dramatic stories set the Bad Faces’ blood boiling. The southerners described the outrage at Sand Creek in all its wretched detail, and told of the persecution of the docile Loafers as well as the hanging of the Lakota Head Men. Crazy Horse in particular was reported to have reacted to these tales of betrayal and brutality with an unconcealed rage for blood vengeance.

The more circumspect Red Cloud also recognized that the white man’s war had finally arrived on his doorstep, first from the east following the troubles in Minnesota, and now from the south. There was nowhere to run. Nor, he reasoned, should his people have to run. It was time, once and for all, to fight the mighty United States and expel the Americans from the High Plains. He had long planned how to do this. The only question had been when. Sand Creek had answered that: Now.

In the early spring of 1865, not long after the southern tribes reached the Powder River Country, the leaders of the Sioux and Cheyenne soldier societies convened a war council on the Tongue. With over 2,000 braves at their disposal, Lakota war chiefs such as Red Cloud, Hump, and Young-Man Afraid-Of-His-Horses plotted strategy with an assortment of Cheyenne counterparts including the regal Dull Knife 1 and the ferocious Roman Nose, who had lost kinsmen at Sand Creek. Although each tribe kept its own laws and customs, all were gradually coming to think of themselves as “The People.” They had the Americans to thank for that.

1. It is a measure of the integration between the Northern Cheyenne and the northern Lakota that this Cheyenne chief, named Morning Star in his own language, was by now almost universally known by his Sioux name, Dull Knife.

Red Cloud was the first to address the gathering. “The Great Spirit raised both the white man and the Indian, ” he told his fellow fighters. “I think he raised the Indian first. He raised me in this land and it belongs to me. The white man was raised over the great waters, and his land is over there. Since they crossed the sea, I have given them room. There are now white people all about me. I have but a small spot of land left. The Great Spirit told me to keep it.”

No more eloquent statement of purpose was required. For once the squabbling bands and tribes were in agreement, and it was decided that after the early summer buffalo hunt—which would prove a particularly cumbersome affair, given the number of mouths to feed— the main force of the coalition would strike the whites at the last crossing of the North Platte on the trails west. This was the Bridge Station outpost, about 130 miles upstream from Fort Laramie. In the meantime, smaller groups of raiders who could be spared from the hunt were sent west, south, and east to keep the soldiers protecting the “Glory Road” and the South Pass of the Rockies off balance, while also gathering intelligence regarding the Army’s movements.

It was a sound plan that leaped to a rousing start in April when a war party of Dog Soldiers burned out a key stage relay station west of Fort Laramie on the Wind River. The Indians killed all five of the station’s defenders and staked their mutilated corpses on trees. A large detachment of cavalry under Fort Laramie’s gallows happy temporary commander, Colonel Moonlight, rode out to hunt the Indians down. But as in the Army’s ineffectual response to Julesburg, Moonlight’s patrol wandered in circles over 450 miles of Wind River country without seeing a hostile. Meanwhile the offending Dog Soldiers had moved east and were raiding the outpost at Deer Creek along the North Platte in conjunction with Lakota riding with Young-Man-Afraid-Of-His-Horses. Through May and June they attacked Wyoming stage stations, emigrant wagon trains, and small Army patrols, scalping and burning from Dry Creek to Sage Creek. On one humiliating occasion a platoon dispatched to chase down raiders returned to Fort Laramie at dusk and reported no Indians within twenty-five miles of the post. They had no sooner unsaddled their horses on the parade ground than a band of about thirty Lakota galloped into the fort, shooting, yelling, and waving buffalo robes. They stampeded the Army mounts through the open gates. They were never caught.

The brazen raids led General Dodge back in Omaha to again vent his spleen on the Laramie Loafers. There were at least 1,500 and probably closer to 2,000 docile Indians living within ten miles of the fort, and in June the general ordered his new field commander, the California General Patrick Connor, to wipe them out. Connor quite sensibly replied that these people were “friendlies, ” and reminded Dodge that if they had not risen after the atrocities on the gallows, he doubted they ever would. Further, he said, if the United States was intent on turning every Indian on the Plains against the whites, a massacre of the Loafers would be a fine start. Dodge blinked. After consulting with the War Department he telegraphed Connor to instead round up the Loafers and transport them southeast to Fort Kearney, where they would ostensibly be taught to farm. Fort Kearney was on the Lower Platte, deep in southern Nebraska: Pawnee country. The Loafers were indeed manageable, but they were not eager to be shipped into the heart of their ancient enemy’s territory.

Nonetheless the Loafers were escorted under armed guard from Fort Laramie in early June, and as they passed the site of the Brule village where Lieutenant Grattan had met his end eleven years earlier, the ghosts seemed to stir them. A few nights later Crazy Horse slipped into their camp and discovered that they were already plotting an escape. He buoyed their spirits when he informed them that a war party of Strong Hearts was lurking just behind the low hills across the North Platte. The next morning, under the pretense of letting their herd graze, the Loafers lured their Army escort into an ambush. Five soldiers, including the officer in charge of the detail, were killed on the very spot where, fourteen years earlier, the Horse Creek Treaty to end all red-white hostilities had been signed. Seven more were wounded. The only Indian casualty was a Sioux prisoner, executed while still in chains.

The newly militant Indians then swam the river with their ponies as the Strong Hearts formed a defensive shield. They rode north. The next day they were pursued by Colonel Moonlight leading a contingent of 235 Ohio, Kansas, and California cavalrymen from Fort Laramie. By the time the hard-riding American force reached Dead Man’s Fork, a small creek flowing into the White River near the Nebraska–South Dakota border, more than a third of the troopers had been forced to turn back after their big American steeds gave out crossing the waterless, hardscrabble tract. The fugitive Loafers and the Strong Hearts had counted on this. They hid themselves amid the thick sage and chokecherries that lined the stream’s steep banks. When what was left of the troop dismounted to water the herd, the Indians sprang. They stampeded and captured the entire remuda, leaving Moonlight and his company to walk back to Fort Laramie over 120 miles of trackless prairie. Moonlight vowed never again to enter hostile territory without proper pickets and hobbles for his mounts, even if it meant disobeying orders. He needn’t have worried. On reaching Fort Laramie, the colonel was relieved of command by General Connor, who cited his incompetence, and shortly thereafter Moonlight was mustered out of the service by General Dodge.

The Army had no idea when, where, or how the hostiles would strike next. But old frontier hands like Jim Bridger assured the officers that it was a long held Indian custom to celebrate even the most minor victories with weeks of feasts and scalp dances. There was time, he said, to amass and mount a large enough force to ride out and surprise them. With this, a degree of complacency settled over the forts and camps along the Oregon Trail. But for once the mountain man was mistaken because Red Cloud was yet again one step ahead of his enemies.

19

BLOODY

BRIDGE

STATION

Buffalo and Indians had

forded the North Platte at the

site of Bridge Station for

centuries. Sometime in the

early 1840's former mountain

men had begun operating

crude ferries to accommodate

the first emigrants crossing

the river en route to Fort

Laramie. And in 1859 the

Missouri Frenchman Louis

Guinard had opened a trading

post on an oxbow near the

ford. Guinard constructed a

1,000-foot bridge spanning

the flow, and soon thereafter

the government expanded his

adobe trading post into a

sturdy redoubt constructed of

lodgepole pine on the river’s

south bank. Telegraph poles

were erected, and a company

of cavalry was deployed to

protect the new line. It was

Red Cloud’s idea to attack

Bridge Station. He knew that

defeating its garrison and

burning the fort and bridge

would halt overland emigrant

traffic for months. Victory at

Bridge Station would also

provide the Indians with an

opening for further incursions

against the smaller Army

camps that had sprouted

along the Oregon Trail. For most of that summer the station had been manned by a feuding mix of Kansas and Ohio men, among them twenty-year-old Lieutenant Caspar Collins of the 11th Ohio Cavalry. As a child Collins had dreamed of fighting Indians, and when he came west in 1862 he was impatient for the opportunity. But after three years on the prairie his natural curiosity had tempered his bloodlust, and he had been known to ride off by himself along the Upper Powder, camping with friendly Oglalas and Brules. There were even reports that in less troubled times Crazy Horse himself had taught Collins bits of the Lakota language as well as how to fashion a bow and arrows. By all accounts Collins was an affable and capable junior officer, with a sterling reputation among the enlisted men. In July, when a large company of Kansas cavalry arrived at Bridge Station, he was bemused more than anything else. “I never saw so many men so anxious in my life to have a fight with the Indians, ” Collins wrote in a letter home. “But ponies are faster than American horses, and I think they will be disappointed.”

Collins’s reflections aside, there was bad blood between his Ohioans and the rough Jayhawkers, and not long after Collins was dispatched to Fort Laramie to secure fresh mounts, the commander of the new Kansas contingent banished most of the Ohio troops to a more isolated post farther west on the Sweetwater. Collins knew nothing of this development as he waited at Fort Laramie to join a patrol riding back to Bridge Station, and it was his bad luck to have still been there when General Dodge’s new field commander General Connor arrived. Connor was yet another of the Army’s hot-tempered Irishmen—he had been born in County Kerry—and in addition to his temper he possessed a constitution as hardy as a Connemara pony’s. He was soon to acquire the Indian nickname “Red Beard” for the ornate copper sideburns that set off his lupine eyes set deep in a face as pinched as a hatchet blade. Connor spotted Collins apparently idling on the parade ground one day, and he tore into the young lieutenant before several witnesses.

“Why have you not returned to your post?”

Collins attempted to explain. The general cut him off.

“Are you a coward?”

Collins was shaken. “No, sir.”

“Then report to your command without further delay.”

Collins rode out the next day. Connor’s rebuke may have been ringing in his ears when Collins reached Bridge Station on the afternoon of July 25 to find only a skeleton squad of his Ohio company still remaining. It was the very day Red Cloud had chosen to attack. The war chief’s tactics were the same as the plan that had nearly worked for the southern tribes at Fort Rankin, near Julesburg. Earlier that morning, before Collins’s arrival, the main body of Cheyenne and Lakota— which included Oglala, Brule, Miniconjou, Sans Arcs, and Blackfoot Sioux warriors— had concealed themselves behind the red sandstone buttes on the north side of the river. But, taking a lesson from the botched ambush at Fort Rankin, Red Cloud had raised a police force from Crazy Horse’s Strong Hearts as insurance in case his excitable braves tried to break cover too early. The Cheyenne recruited members of their own Crazy Dog Society to do the same. Red Cloud then sent a dozen or so riders in full battle regalia out into the little valley fronting the station, hoping to draw out most of its 119 defenders.

At first a howitzer battery seemed to have taken the bait, but after crossing the bridge the cannoneers moved no farther, opting to dig in on the north bank of the river and merely lob shells into the hills. Red Cloud was restless but waited until the tangerine twilight turned to charcoal dusk before signaling for the decoys to return. That night he altered his plan and selected a small party of Bad Faces to creep into the culvert beneath the north side of the bridge and hide themselves amid the brush and thick willows. At dawn he again deployed his baiting riders, who this morning cantered even closer to the fort and taunted the soldiers by shouting obscenities, in English, that they had learned from traders.

Again the ploy looked to have worked. The gates opened and at the head of a column of cavalry rode Lieutenant Collins. Red Cloud had no idea that the horsemen were coming out not to fight the decoys, but to escort into Bridge Station five Army freight wagons returning from delivering supplies to the Ohioans on the Sweetwater. By this time even the rawest recruit on the frontier was aware of the Indians’ repeated use of a handful of braves to lay a trap. Collins had also been warned. Earlier that morning, as he donned the new dress uniform that he had purchased at Fort Laramie, several of his remaining Ohioans had tried to dissuade him from riding out with only twenty-eight men. When he persisted they implored him to at least request from the Kansan commander a larger detail. Again Collins said no, and at this a fellow officer from his regiment handed him his own weapons, a brace of Navy Colts. Collins stuck one into each boot, selected a high-strung gray from the stable, and mounted up at 7:30. Before departing he handed his cap to his Ohio friend “to remember him by.”

The decoys scattered as Collins and his troop crossed the bridge, followed on foot by the Ohio men and a few Kansans with Spencer carbines, eleven soldiers in all, acting as a volunteer rear guard. They watched from the riverbank as the riders moved half a mile into the North Platte Valley. The hills then erupted with painted warhorses, pinging arrows, and glinting steel. The Lakota swept down from the northern buttes, and the Cheyenne rode in from the west. On Collins’s orders the little column wheeled into two ranks and discharged a volley from their carbines. A bitter-tasting fog of smoke rolled toward the river. Then Collins flinched and nearly toppled from his horse. He had been shot in the hip, and a scarlet stain seeped through his pants leg. By the time he regained his balance there were so many Indians swarming his column that lookouts on the Bridge Station parapets lost sight of the Bluecoats in the swirling dust. Except for one. Lieutenant Caspar Collins, an arrow buried deep in his forehead, was clearly visible for a moment before he and his horse disappeared into a scrum of charging braves.

Indian and American horseflesh continued to collide at close quarters, the Indians slashing with knives and spears and swinging tomahawks and war clubs to avoid firing into their own lines. The unwieldy carbines were now useless, and cavalrymen fought back with revolvers. A galloping horse broke out of the smoky haze with a wounded trooper hunched over its neck, making for the bridge. Another followed. Then another. The rear guard opened up with the Spencers, firing wildly into the melee. As if by magic the Bad Faces hidden beneath the span appeared. They threw their bodies in front of the retreating horsemen. The rear guard charged them, desperate to keep the escape route open. Riderless horses and single riders with arrows protruding from all parts of their bodies galloped back through the pandemonium. A cannon boomed from the Bridge Station bastions, and soldiers on the catwalks watched an Indian drive his spear through the heart of a dismounted cavalryman, yank it out, turn, and lunge at another, piercing his chest. But the second soldier was not dead. He fell forward, pressed his revolver against his assailant’s head, and with his last cartridge blew out the Indian’s brains.

Thirty minutes into the fight Red Cloud signaled the Cheyenne chief Roman Nose to break off his Dog Soldiers. They thundered up the valley toward the approaching freight wagon train. The train’s five lead scouts, cresting a rise in the road that put them in sight of the fort, saw a horde of 500 Indians bearing down on them. The scouts galloped for the river and splashed their mounts into the current. Three made it across. The men at the bridge who had formed the rear guard, including the lieutenant who had given Collins his revolvers, retreated to the stockade. The lieutenant volunteered to lead a rescue detachment, reminding the post commander that the twenty wagoneers were also men from the 11th Ohio Cavalry. The Kansan refused, insisting that he needed every available body to defend the fort. The lieutenant punched him in the face, was subdued, and was taken to the guardhouse at about the time Roman Nose descended on the freighters, just reaching the same ridgeline as the scouts.

💀 💀 💀

The Ohio teamsters

recognized that it was suicide

to try to burst through so

many hostiles. They made for

a shallow hollow between the

road and the North Platte.

They formed the best corral

possible with their five

wagons and a few empty

wooden mess chests, and

attempted to hobble their

thirty mules. But an Indian

captured the bell mare and led

her off, the rest of the animals

following. With her went

their last chance of escape.Americans dropped one by one over the succeeding four hours; but the Indians’ arrows and muskets were no match for the soldiers’ breech-fed, seven-shot Spencer carbines, and the survivors managed to hold off their circling attackers. By mid-afternoon the Indians decided to take a new tack, slithering closer on all sides through shallow trenches they scraped out of the sandy soil with knives and tomahawks, rolling logs and large boulders before them. The besieged troop, holed up below the road, could not see them. But the men on the fourteen-foot walls of Bridge Station did. They fired howitzer shells as a warning, but the meaning of the signal was lost on the teamsters. By four o’clock the Indians had crawled to within yards of the makeshift stockade. All went quiet; then came a shrill shriek. The Indians rose by the hundreds, “seeming to spring from the very ground, ” according to one historian. A fire broke out and soldiers on the Bridge Station walls could hear screams but could see nothing through the thick black smoke. The Indians were burning both men and wagons.

Night fell and the Lakota and Cheyenne returned to the hills while the post commander at Bridge Station counted twenty-eight men missing and presumed dead, twice as many wounded, and perhaps half left to fight. The telegraph lines east of the fort had been cut, and at ten o’clock a half-blood scout mounted a captured Indian pony and slipped through a side gate with instructions to ride for Deer Creek Station twenty-eight miles to the east. From there word could be transmitted to General Connor at Fort Laramie. The scout made it through.

On the far side of the red bluffs the day ended just as inconclusively for Red Cloud. There is no record of his losses, but the Army estimated that sixty Indians had fallen. Though this number was probably inflated, it was still a significant toll. Moreover, not only had the Native force failed to take the outpost, but a good number of Collins’s cavalry had managed to make their way back through the Bad Faces and across the bridge to safety. The Cheyenne Dog Soldiers blamed the Lakota, a few even insinuating that the Lakota were cowards. The Lakota moved for their weapons but were held back at the last moment by the frustrated Red Cloud’s authority.

Red Cloud and Roman Nose spent the night repairing the damaged alliance, and the next morning the great war party paraded before Bridge Station just beyond cannon range, then swung back into the hills and vanished. Red Cloud recognized that despite his superior numbers, most of his fighters, his Oglalas and Brules in particular, were far too inexperienced, ill disciplined, and uncomprehending of tactics to lay siege to the Army outpost. Even more disturbing was the way the tribes had nearly turned on each other. The best he could hope for was that as the war progressed his followers would learn. He was probably asking too much.

20

THE HUNT

FOR RED

CLOUD

It is not recorded if, on

learning of Caspar Collins’s

death, General Connor

expressed any remorse over

his verbal lashing of the

young lieutenant. But it is

known that when news

reached Connor of the fight at

Bridge Station—soon to be

renamed Fort Caspar and

eventually the site of

Wyoming’s state capital—he

chafed to ride against the

hostiles. The conclusion of

the Civil War had finally

made this possible. Though

not technically a peace treaty,

the surrender of Robert E.

Lee’s Army of Northern

Virginia at Appomattox

Courthouse in April 1865

marked the de facto end of

hostilities, and thus of the

Confederacy. It also meant

that the battered Army of the

Republic was able to replace

the raw state militias

patrolling the west with

seasoned troops better

capable of confronting the

Indians of the Great Plains.

South of the Arkansas, this

meant eradicating the Kiowa

and the Comanche, who were

blocking movement along the

Santa Fe Trail into New

Mexico. North of the Platte, it

meant killing Red Cloud and

Sitting Bull.General Ulysses S. Grant, the Army’s commander in chief, had long planned such a moment. The previous November, the day after the Sand Creek massacre, Grant summoned Major General John Pope to his Virginia headquarters to put such plans in motion. Despite his relative youth, the forty three-year-old Pope was an old-school West Pointer and a topographical engineer surveyor whose star had risen with several early successes on western fronts in the Civil War. It had dimmed just as rapidly when Lincoln placed him in command of the eastern forces; Pope was thoroughly outfoxed by Stonewall Jackson and James Longstreet at the Second Battle of Bull Run. Pope had been effectively exiled to St. Paul, Minnesota, until Grant recalled him to consolidate under one command a confusing array of bureaucratic Army “departments” and “districts” west of St. Louis. Grant named Pope the commanding general of a new Division of the Missouri, into which he enfolded three fractious geographic departments: Northwest, Missouri, and Kansas. This new division was also enlarged to include Utah and parts of the Dakotas. Pope’s mandate was to execute an offensive in the summer of 1865 that would, among its prime objectives, make safe the trail stamped out by John Bozeman.