Surprise,Kill, Vanish

By Annie Jacobson

Part 1

Chapter 1

An Office for

Ungentlemanly Warfare

It was the first Sunday in December 1941, and the boy selling popcorn behind

the concession stand at the Strand Theatre in Bastrop, Texas, had just turned

twelve. His name was William Dawson Waugh, but everyone called him Billy.

Shortly after 2:00 p.m., Sheriff Ed Cartwright walked into the theater with a

terrible look on his face. He told Billy Waugh to run upstairs, have the

projectionist shut off the film, and turn on the lights. Taking the stairs two at a

time, Waugh did as instructed. From high above in the projectionist’s booth he

watched as the room full of moviegoers squinted and complained about the

movie being interrupted. Then Sheriff Cartwright walked onto the stage and

everyone fell silent.

“Listen up,” the sheriff said. “The Japanese just attacked Pearl Harbor.” The

U.S. Pacific Fleet was destroyed and thousands of Americans were dead. What

would happen next was anyone’s guess, the sheriff said, but it would be

foolhardy to rule out the possibility of another attack. Sheriff Cartwright told

everyone to go home and cover their windows with blackout material. Listen to

the radio and stay informed.

Billy Waugh stayed behind, watching the moviegoers file out. After he

finished cleaning up, he went home to the house where he lived with his mother,

Lillian, a part-time schoolteacher, and his older sister Nancy. The next day,

Congress declared war on Japan. Three days after that, Adolf Hitler declared war

on the United States, and Congress then declared war on Germany and Italy.

With America at war around the world, Billy Waugh made a vow to himself: one

day I’ll go to war, too.

The day Pearl Harbor was bombed in a surprise attack remained imprinted on

his mind. By that time, 1941, Billy Waugh knew more about war than most

twelve-year-old boys. He’d been absorbing information from the newsreels that

played before Strand Theatre films. Hitler’s campaign, Blitzkrieg, or lightning

war, astounded him. This idea of total war, of all-out victory at any human cost,

was mind-boggling and frightening.

“It is not right that matters, but victory,” Hitler told his generals. “Act

brutally!… Be harsh and remorseless… the success of the best is by means of

force…”

Of all the tactics and techniques being used by the Nazis in the invasion of

western Europe, it was the boldness of the paratrooper unit (Fallschirmjäger) that

left Billy Waugh thunderstruck. Newsreel films showed Nazi commandos

leaping out of airplanes and parachuting into the war theater to launch deadly

surprise attacks. Then there was the paraglider attack at the Belgian fortress

Eben Emael, once considered the most impenetrable fortress in the world.

Seventy-eight Nazi paratroopers, piloting gliders and armed with flamethrowers,

landed on the rooftop of the fortress, and overtook 650 Belgian defenders—a

victory from which the Belgian Army never recovered. One month after the

Nazis captured Eben Emael, the U.S. Army created its own paratrooper division

in Fort Benning, Georgia, the first in American history.

Every spare moment Billy Waugh had, in between school and the three part time jobs he worked—as a paperboy, stock boy, and popcorn popper—he

gathered information about these U.S. paratroopers. The most important items

for a successful parachute jump, he learned, were the boots. They were tall, to

mid-shin, with rawhide laces and stitching across the toe. Billy Waugh became

focused on owning a pair of his own. His alcoholic father had died of cirrhosis of

the liver when Billy was ten. The money he earned from his after-school jobs

went to his mother, to help pay for the family’s living expenses. Now, with a

clear goal in mind, he began skimming nickels and dimes off his earnings. When

he finally saved up seven dollars, he hitchhiked thirty miles to Austin and bought

himself a pair of paratrooper boots. Elated, he felt a step closer to one day

becoming a U.S. paratrooper. The world was all right.

Across the Atlantic, war raged in Europe. It was May 27, 1942, and in the Czech

town of Holešovice the Nazi general riding in an armor-plated Mercedes-Benz

had been targeted for assassination. SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich

was a Janus-like creature: blond, blue-eyed, and beautiful, his skin smooth and

pale like that of a porcelain doll, but he was also a monster, cruel and sadistic

beyond measure. His own boss, Adolf Hitler, described Heydrich as a man with

an iron heart. A secret unit inside British intelligence sought to kill him. The

assassination plot was called Operation Anthropoid.

Concealed on a hillside not far from where Heydrich was driving his

Mercedes, two British-trained assassins lay in wait. Jan Kubiš and Josef Gabčík,

both Czech nationals in their mid-twenties, were members of a classified British

commando unit that existed inside the British Secret Intelligence Services,

Section 6—MI6. Only an elite few were aware that these commando units were

part of an underground paramilitary army working under the bland-sounding

cover name Special Operations Executive. Kubiš and Gabčík had been assigned

to SOE’s Division D, for destruction, and their work was based on

unconventional-warfare tactics, also called guerrilla warfare.

The existence of SOE was a source of great controversy within the British

military establishment. Most British generals believed war was first and

foremost about chivalry and honor. That it must be fought in adherence to the

laws of war. While no single document can be identified as the ancient source

from which the laws of war have evolved, modern-day codes of conduct stem

from the Lieber Code, a set of 157 rules written by lawyer and university

professor Francis Lieber during the American Civil War. Issued on April 24,

1863, by President Abraham Lincoln as General Orders No. 100, these rules

were to serve as a uniform code of conduct governing the behavior of the Union

Army, the Confederate Army, and the armies of Europe. They were later

expanded upon in Hague Convention resolutions of 1899 and 1907. Rule 148 of

the Lieber Code explicitly prohibited assassination. “Civilized nations look with

horror upon offers of rewards for the assassination of enemies as relapses into

barbarism,” Lieber wrote. Guerrilla fighters were labeled “insidious” enemies

and therefore not entitled to the protections of the Laws of War.

War, like sport, was to be a gentleman’s game. Guerrilla warfare was most

ungentlemanly, based as it was on treacherous principles like sabotage and

subversion. Sabotage during World War II meant blowing up trains, bridges, and

production plants behind enemy lines—situations in which civilians would likely

be killed. Subversion, or undermining the authority of an occupying force,

required a host of dirty tricks and deceptive acts, including assassination. But

Prime Minister Winston Churchill believed that SOE Division D was necessary,

and he personally approved of every mission it undertook. Because guerrilla

warfare in general, and SOE operations in particular, were considered

ungentlemanly, the SOE became known as Churchill’s Ministry of

Ungentlemanly Warfare.

Commandos like Kubiš and Gabčík were trained to infiltrate enemy-occupied

territory, perform hit-and-run operations, and then disappear. The short-term goal

of their efforts was to create paranoia among Nazi officials and embolden

underground resistance movements. The long-term goal of the SOE was to

prepare the battlefield for an upcoming Allied invasion.

In Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia, Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich

was in charge. He was also one of the most influential and powerful generals in

the vast Nazi war machine. Heydrich reported directly to Heinrich Himmler, the

ambitious, sadistic Reichsführer whose evil knew no bounds. Heydrich created

and supervised the Einsatzgruppen, extermination squads whose 3,000 members

shot and killed more than one million men, women, and children during the war.

He served as one of the main architects of the Final Solution and personally

initiated the deportation and mass murder of European Jews. In 1942, he was at

the top of SOE’s kill list.

At SOE, the Heydrich assassination operation was handled jointly by two

men, Major General Sir Colin McVean Gubbins, a decorated World War I hero

and SOE’s director of operations, and František Moravec, the former chief of

Czech military intelligence, then living in England in exile. As with most SOE

commandos, Jan Kubiš and Josef Gabčík had been handpicked for bravery,

cunning, and a willingness to ruthlessly kill. “The whole art of guerilla [sic]

warfare lies in striking the enemy where he least expects it, and yet where he is

most vulnerable,” Gubbins instructed his men. “Inflict the maximum amount of

damage in a short time and get away.”

The SOE considered assassination a necessary dark art, a way to weaken the

Nazis’ impenetrable hold on power. A successful operation required months of

planning by Gubbins and Moravec, followed by months of intense training and

rehearsing by Kubiš and Gabčík. Much of the work took place in a classified

SOE facility in Scotland code-named Training Center STS 25. Here, the

assassins trained in guerrilla warfare tactics including hand-to-hand combat,

sharpshooting, cover and concealment, and the manufacture of homemade

bombs. They learned map reading and code deciphering. How to slit the throat

of a sentry or guard without making a sound. Finally given the green light, Kubiš

and Gabčík were flown in under cover of darkness by a British pilot and a crew

of five. They jumped out of the aircraft over a village just east of Prague and

parachuted in behind enemy lines. Safely on the ground, the two commandos

met up with resistance fighters who hid them from discovery until they were

ready to strike. On May 27, 1942, the moment arrived.

There, in Nazi-occupied Holešovice, Kubiš and Gabčík lay camouflaged in

the grass. They’d arrived to the target area on bicycles, now stashed in a nearby

grove of trees. Each man had a pistol in his pocket. Gabčík carried a Sten

submachine gun. Kubiš held the assassination weapon: an antitank grenade that

had been specially modified by British explosives expert Cecil Clarke. The small

bomb needed to be powerful enough to shatter the armored plating on

Heydrich’s Mercedes, so as to kill him, but light enough to be accurately thrown

by Jan Kubiš.

High on the hill above the assassins, a signal mirror flashed. Heydrich’s

Mercedes had been spotted by a local Czech accomplice, Josef Valčik. Soon the

car would round the corner and approach where Kubiš and Gabčík were

concealed. The planning had been meticulously mapped out. The geography of

the land was such that at mid-hill, the road twisted in a hairpin turn, meaning

Heydrich’s chauffeur would be forced to brake and slow down. Kubiš and

Gabčík would have a five-second window to kill Reinhard Heydrich and flee.

As the car made its way down the hill, the assassins could see that the top of

Heydrich’s Mercedes 320 Convertible B was open wide. Opportunity at hand,

Gabčík stood up, released the catch on his Sten submachine gun, and rushed

toward the sharpest point in the road’s curve. As the Mercedes braked and

decelerated, Gabčík took aim and fired, bracing himself for a powerful explosion

of gunfire. Instead, a catastrophic misfire. Nothing but the impotent click of the

weapon as it failed to fire. Gabčík, now standing there in the road, was mortally

exposed.

Heydrich’s driver screeched to a full stop. SS-Oberscharführer Johannes

Klein was an imposing Nazi chauffeur and bodyguard. Six foot three, he was

trained in the art of tactical military driving. Had he followed Third Reich

protocol, Klein would have accelerated and sped away. But Heydrich apparently

ordered Klein to stop the car. With Gabčík still standing next to the Mercedes,

Heydrich pulled his Luger from its holster, stood up in the convertible, and

began shooting at Gabčík. What Reinhard Heydrich failed to realize was that a

second SOE-trained assassin was nearby.

Jan Kubiš moved into action. Following protocols learned over months of

SOE commando training, he stepped forward and hurled the incendiary device

into Heydrich’s Mercedes. In the chaos of the moment, he missed. Instead, the

bomb exploded against the car’s right rear fender, sending glass and metal shards

flying through the air. Reinhard Heydrich was hit by debris. Not realizing he’d

been wounded, Heydrich got out of the car and continued firing. Ditching his

faulty submachine gun, Gabčík returned fire with his pistol. Enraged, Heydrich

lumbered toward his assassin as Gabčík sought cover behind a telephone pole.

As the smoke from the car bomb cleared, Kubiš emerged bleeding from a head

wound. One witness described blood pouring down his forehead into his eyes.

Klein exited the car and began firing at Kubiš. Improbably, the bodyguard’s gun

also jammed, affording Kubiš time to flee.

Gabčík remained pinned down behind the telephone pole, engaged in a lethal

exchange of gunfire with Heydrich. But as Heydrich charged, still firing at

Gabčík, he suddenly and dramatically collapsed in the road. The debris from the

bomb had penetrated his skin and lodged in his organs. Adolf Hitler’s powerful

deputy lay stricken on the pavement, unable to move.

“Get that bastard!” Heydrich shouted at Klein, pointing in the direction of

Gabčík as he fled. The chauffeur chased the assassins across a field, leaving

Heydrich writhing in pain on the road. Kubiš and Gabčík escaped.

Heydrich was rushed to nearby Bulovka Hospital, where three of the Nazis’

most senior doctors came to his aid. Theodor Morrell, Hitler’s personal

physician, Karl Brandt, Nazi health commissioner, and Karl Gebhardt, chief

surgeon of the Waffen-SS, concluded that Heydrich’s diaphragm was torn and

that grenade fragments were embedded in his spine—not necessarily life threatening injuries. But the three physicians overlooked the fact that tiny bits of

horsehair from the upholstered seats of the Mercedes had lodged into Heydrich’s

spleen. Just a few days later, on June 4, 1942, the man with the iron heart died

from septicemia, or blood poisoning.

When Hitler learned of Heydrich’s assassination, he became enraged.

Privately, he blamed Reinhard Heydrich for his own careless death. “Since it is

opportunity which makes not only the thief but also the assassin, such heroic

gestures as driving in an open, unarmored vehicle or walking about the streets

unguarded are just damned stupidity, which serves the Fatherland not one whit,”

Hitler said on the day Heydrich died. “That a man as irreplaceable as Heydrich

should expose himself to unnecessary danger, I can only condemn as stupid and

idiotic.” Publicly, Hitler demanded revenge. That the assassins had been able to

escape and go into hiding was an outrageous insult to the Third Reich. At

Heydrich’s funeral in Berlin, Hitler ordered his ministers in Prague to find the

assassins, or else.

The reprisals were brutal, indiscriminate, and far-reaching. “The barbaric

idea was to terrify the Czech people by completely destroying a village at

random,” said František Moravec, former chief of Czech military intelligence

and the man who’d trained the assassins. Northeast of Prague, the Gestapo

cordoned off Lidice, rounded up all 173 male inhabitants, and executed them in

the village square. Three hundred women and children were sent to Ravensbrück

concentration camp for extermination. The houses in the village were set on fire,

then bulldozed over so no trace remained. “The operation was executed with

such thoroughness that even the persons who happened to be absent from the

village on the night of the destruction were gradually located and executed,” said

Moravec.

A reward of one million reichsmarks was offered for information on the

assassins’ whereabouts. A local Nazi collaborator named Alois Kral revealed that

Jan Kubiš and Josef Gabčík were hiding in the basement of a Russian Orthodox

church in Prague. Nazi commandos stormed the church, and when they

determined that Kubiš and Gabčík were located in the tunnels below, they

flooded the basement with water. Kubiš tried to fight his way out but was

mortally wounded. Gabčík, knowing he would soon be killed or captured,

swallowed a cyanide pill given to him by the SOE. Both men’s bodies were

recovered and buried in a mass grave.

The reprisals did not end in Lidice. Five days later, Nazis razed Ležáky after

a shortwave radio transmission was found to have been sent from the village to

the British. All thirty-three residents and their children were killed. The

following week, 115 people accused of being members of the Czech resistance

were executed. Heydrich’s successor, SS General Kurt Daluege, boasted that in

retaliation for killing Reinhard Heydrich, 1,331 Czech citizens were executed

and another 3,000 Jews exterminated. Was it worth it? Five thousand Czechs

“paid with their lives for the death of a single Nazi maniac,” Moravec lamented

after the war.

In 1945, after the Germans surrendered, Moravec returned to Prague to speak

with Alois Kral, imprisoned and awaiting trial for Nazi collaboration.

“Greetings, brother,” Kral said sarcastically to Moravec when the two men

met.

“Brother?” asked Moravec, astonished.

“I killed two Czechs. You killed five thousand. Which of us hangs?” Kral

asked.

It was Kral who was hanged; General Moravec watched the execution. By

then, Czechoslovakia had become part of the Communist Soviet bloc. After the

execution, as Moravec walked away, he stopped to ask a question of a

communist functionary—a Czech national—a man familiar with the Heydrich

case.

“Will you please tell me where Kubiš and Gabčík are buried?” Moravec

asked.

“Nowhere,” came the abrupt answer. “There are no graves. You foot-kissers

of the British are not going to have that excuse to build a statue and hang

wreaths. Czech heroes are Communists now.”

And so it goes. Wars are fought. One side wins, the other side loses. Some go

home. Others become casualties. Freed from Nazi rule, the Czechs lived under a

communist-led government that answered to another tyrant, Josef Stalin.

For the second time in a decade, František Moravec fled his country, this time

for America. There, the former head of Czech military intelligence took a job as

an advisor to the U.S. Department of Defense, where he worked until suffering a

heart attack in 1966. He died in the parking lot of the Pentagon, seated in the

front seat of his car.

To the SOE, the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich was necessary and

justified. The spectacle killing of a top Nazi general poked holes in the armor of

the Nazi war machine. To the general Czech population, it made the strong

appear weak. Inside the Third Reich, the meticulously planned and executed

assassination operation gave rise to fear and paranoia among other Nazi officials.

When Winston Churchill was briefed on Operation Anthropoid, he expressed

approval. When U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt asked whether the British had

a hand in Heydrich’s assassination, Churchill is said to have winked.

In Washington, DC, a retired World War I general and recipient of the Medal

of Honor named William J. Donovan had been trying for years to get President

Roosevelt to authorize an unconventional-warfare organization modeled after

SOE. Two weeks after Reinhard Heydrich’s assassination, Donovan got his wish.

As per Executive Order 9182, the Office of Strategic Services was born, a

closely held secret at the time but now famously known as the wartime

predecessor of the CIA. Under the authority of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, OSS

would work in partnership with SOE. William J. Donovan was made director,

and within days of its creation, recruiting for OSS was in full swing.

At Fort Polk in Louisiana, U.S. Army officer Aaron Bank, 40, was restless and

bored. It had been seventeen months since the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor and

the same amount of time since Bank had requested troop assignment. He was

burning to see combat, but in the eyes of the U.S. Army, Aaron Bank was too

old. And so instead, he’d been assigned to a railroad battalion, overseeing

soldiers lay tracks connecting Fort Polk to Camp Claiborne, fifty miles away.

“My spirits were low with such unrewarding duties,” he told a friend.

One day in the spring of 1943, passing the adjutant’s tent, Bank spotted a

notice on a bulletin board. The army was looking for volunteers. The notice

read: “Likelihood of a dangerous mission guaranteed.” Knowledge of French or

another European language was the only requirement, but volunteers would need

to qualify as paratroopers.

“My pulse quickened,” Bank later recalled, “a ray of hope appeared.” Fluent

in French and eager to jump out of airplanes, Bank signed up. A few days later,

he received orders. He was to report to the Q Building in Washington, DC,

wearing civilian clothes. Aaron Bank did not yet know it, but he’d been assigned

to the OSS, to its Special Operations Branch, the American equivalent of SOE’s

Division D. The mandate of the Special Operations Branch was to “effect

physical subversion of the enemy,” in three distinct phases: infiltrate, prepare the

battlefield, and conduct sabotage and subversion. Bank was assigned to the

French Operational Group for Operation Jedburgh.

Initial training took place at a secret facility in Prince William Forest Park, in

Virginia, that went by the code name Area B. Volunteers learned right away the

kinds of commando operations they were being prepared for. “Either you kill or

capture, or you will be killed or captured,” the Jedburghs were told, an

instruction that was emphasized by the Fairbairn-Sykes OSS stiletto knife issued

to members. This double-edged weapon, designed exclusively for surprise attack

and killing, resembled a dagger. Its foil grip and slender blade made for easy

penetration into a man’s rib cage. How best to use the now legendary Fairbairn-Sykes stiletto in hand-to-hand combat was taught to the Jedburghs by Lt. Col.

William E. Fairbairn, one of the knife’s designers. “In close-quarters fighting

there is no more deadly weapon than the knife. An entirely unarmed man has no

certain defense against it,” Fairbairn explained. Of Fairbairn’s training, a young

recruit named Richard Helms had this to say: “Within fifteen seconds, I came to

realize that my private parts were in constant jeopardy.” Helms would one day

serve as the eighth director of Central Intelligence.

In addition to the art of knife fighting, Jedburghs learned pistol shooting and

grenade throwing. How to kill a man with a pencil to the throat, how to garrote

an enemy with piano wire. In evade-and-escape training they practiced rope

climbing and map reading, how to cross a raging river and scale a cliff. To

master the art of sabotage, the Jedburghs learned to construct bombs powerful

enough to blow up bridges, canal locks, and industrial plants. To infiltrate

territory laced with land mines, they practiced on an obstacle course laced with

small explosive charges and called Demolition Trail. Trainees were told to keep

their heads down and stay low. The only injury recorded was sustained by a

young officer who broke his jaw and lost several teeth in a small explosion. The

injured commando, William J. Casey, would one day serve as the sixteenth

director of Central Intelligence, under President Ronald Reagan.

The OSS trained its agents to work from a mind-set that was diametrically

opposed to U.S. Army doctrine at the time. Conventional warfare was based

upon frontal assault against an enemy’s main line of resistance. On colossal tank

battles, combined with air power, and army ground force assault. Guerrilla

warfare—also called unconventional warfare and irregular warfare—was the

opposite. Close-quarters combat and throat slitting were par for the course.

Whereas infantry soldiers followed strict orders within a chain of command,

Jedburghs were trained in the art of self-reliance. They were volunteering for

mysterious, often solo assignments involving improvisation on the ground. OSS

chief William Donovan believed in the necessity of guerrilla warfare, a

sentiment he conveyed to President Roosevelt, in a letter housed at the National

Archives. “My observation is that the more the battle machines are perfected, the

greater the need in modern warfare of men calculatingly reckless with

disciplined daring, who are trained for aggressive action,” Donovan said. “It will

mean a return to our old tradition of the scouts, the raiders, and the rangers,” he

insisted in a reference to the unconventional-warfare tactics used during the

American Revolution.

To understand and embrace OSS-style guerrilla warfare was to reject

preconceived notions of honor, chivalry, and fair play as the gentleman’s way of

war. “What I want you to do is get the dirtiest, bloodiest, ideas in your head that

you can think of for destroying a human being,” SOE’s founder, General

Gubbins, educated the Jedburghs. “The fighting I’m going to show you is not a

sport. It’s every time, and always, fight to the death.”

After six weeks, Aaron Bank and fifty-five American Jedburghs were sent to

England for more advanced training, this time with their British, French, and

Belgian counterparts. On the Scottish shores of Loch nan Ceall, at a Victorian

lodge called Arisaig House, the Jedburghs learned how to operate under extreme

duress, how to stay awake for days on end, hike one hundred miles, raid a

building, seize a small town. Finally, in a last phase of training, the multinational

Jedburgh teams were sent to a manor house in Cambridgeshire called Milton

Hall. One of the largest private homes in England, the manor had been donated

to the cause by Lord and Lady Fitzwilliam. Oil portraits of Fitzwilliam family

ancestors dating back to 1594 hung on the walls. In the massive sunken gardens,

the Jedburghs practiced martial arts. In the converted dairy barns they learned to

decode cipher, feign deafness, use sign language, and transmit Morse code. In

the manor’s grand library they watched Nazi propaganda films, a way to become

familiar with how the enemy moved, spoke, and dressed. Milton Hall served as a

kind of finishing school for commandos, one of the last stops before embarking

on dangerous missions that many would not survive. Jan Kubiš and Josef Gabčík

trained at Milton Hall shortly before leaving on their mission to kill Heydrich.

The final phase of Jedburgh training involved parachuting infiltration

techniques, taught in Altrincham, Manchester, at a facility code-named STS-51.

This three-day educational course included three live parachute jumps. The first,

in daylight, was out of a balloon flying 700 feet off the ground. The second was

out of an airplane flying at an altitude of roughly 500 feet. The third served as a

dry run for insertion behind enemy lines; in the dead of night, commandos

jumped out of a plane flying at roughly 1,500 feet.

On June 5, 1944, the eve of the Normandy invasion, the first Jedburgh team,

code-named Team Hugh, parachuted into Nazi-occupied France with instructions

from Prime Minister Winston Churchill to “set Europe ablaze.” Ninety-two

Jedburgh teams would follow, including one led by Aaron Bank, now advanced

to chief of guerrilla operations in France. The mission of these Jedburgh teams

was to blow up infrastructure, kill Nazis, and disappear without a trace. In this

way the official motto of the Jedburghs became “Surprise, Kill, Vanish.”

In Texas, Billy Waugh learned about the Normandy invasion from the radio at

his grandmother’s house. Winnie Waugh lived directly across the street, and

whenever Billy had the chance, he listened to programs like GI Live and This Is

Our Enemy. On the afternoon of June 6, 1944, NBC Radio announced the D-Day

invasion of Nazi-occupied France. Then came the newsreels of the Normandy

invasion. The most amazing footage was of fifteen hundred airplanes dropping

thousands of American paratroopers into France, their silk canopies filling the

skies like balloons. To Billy, these operations were mythic, and when he heard

that recruiting stations in Los Angeles, California, allowed boys of fifteen to

pass for older and join the war, he decided to run away and become a combat

soldier.

Billy Waugh packed a bag and hit the road, hitchhiking west out of Bastrop.

He made it 650 miles, to Las Cruces, New Mexico, where he was stopped along

Highway 80 by a police officer. When he failed to produce identification, he was

arrested for truancy and put in jail. The police said they’d release him only if he

could produce enough money to buy a bus ticket back home. With no choice but

to call his mother, Billy Waugh picked up the phone. His mother agreed to wire

him bus fare if he promised to finish high school. Billy kept his word. This war

would end without him, but he was now determined to become a U.S. Army

paratrooper first thing after high school.

In Europe, as part of a plan called Operation Foxley, the British Special

Operations Executive conceived of ways to assassinate Adolf Hitler. One plot

called for a sniper to shoot Hitler during his morning walk around the Berghof,

his residence in the Bavarian Alps, using a Mauser Kar 98k with a telescopic

sight. Another plan involved sending a single commando into Nazi Germany to

poison Hitler’s food with an unidentified toxin, code-named “I.” In a third plot,

commandos would attach a suitcase full of explosives under the Führer’s train

car. But the laws of war forbade assassination, and many British generals

worried that such a high-profile assassination could open the door to a war

crimes trial.

Not everyone agreed. On the pro-assassination side was Air Vice Marshal A.

P. Ritchie, who told colleagues that the German people viewed Hitler as

“something more than human.” To Ritchie, it was “this mystical hold which

[Hitler] exercises over the German people that is largely responsible for keeping

the country together at the present time.” In a bid for assassination, he argued,

“Remove Hitler and there is nothing left.” But Vice Marshal Ritchie was a

minority voice. Decades earlier, in 1907, forty-four nations had met at The

Hague to formalize the laws of war as had been originally written in the Lieber

Code. In Laws and Customs of War on Land (Hague, IV), assassination was

further defined to include any form of “treacherous killing.” Wartime killing had

sharp distinctions, the authors wrote, citing by example two contradictory ways

to kill a general or king—one considered a treacherous war crime, the other a

lawful killing. A soldier is forbidden to sneak into the tent of a general or king

disguised as, say, a peddler. But if that soldier is in uniform, and is part of a

small attacking force, then he is allowed and encouraged to kill the general or

the king. One soldier is a “vile assassin,” the other “a brave and devoted soldier,”

according to the Hague Convention. The reason for the distinction, the authors

wrote, was to diminish the “evils of war.”

And so—despite how arbitrary this and other prohibitions seemed to some—

the British SOE’s plans to assassinate Hitler were scrapped. There was no way

an SOE commando could operate inside Nazi Germany wearing a uniform of the

British Army, it was argued. But over at the Office of Strategic Services, the

boldness of Operation Foxley inspired the OSS chief of secret intelligence for

operations in Europe to devise a Hitler assassination plot of his own. The chief

was a young American lawyer turned commando named William J. Casey, the

same young man who’d broken his jaw and lost several teeth on the Demolition

Trail while training for OSS Special Operations at Area B.

To Casey’s eye, if OSS was going to defy the Laws and Customs of War on

Land in order to assassinate Hitler, why stumble over a rule regarding uniforms?

His audaciously deceptive plan, called Operation Iron Cross, was to insert an

OSS commando team disguised as enemy soldiers wearing Nazi uniforms. To

lead this five-man OSS team, which would be populated out by a battalion of

turncoat Nazis, Bill Casey chose Aaron Bank. The two men had trained together

back at Prince William Park in Virginia, at Area B.

After the war, Aaron Bank recalled Bill Casey describing Operation Iron

Cross to him as the most important assassination operation of the war. The OSS

had recently captured, turned, and trained 175 German POWs. These men,

formerly avowed Nazis, were now willing to work for the OSS. In the winter of

1945 the plan was to have Aaron Bank, a four-man OSS team, and the captured

Nazis parachute in behind enemy lines, posing as Wehrmacht soldiers. The team,

called the OSS Iron Cross Mountain Infantry, would hike through the

mountainous terrain, locate Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest hideaway, ambush the Nazi

leader, and kill him. But to command such a unit deep in enemy territory

involved extreme risk. The drop zone chosen would be deep within the Inn

Valley, in Austria. There would be no backup air support, no infantry army to

call. All it would take was one double-crosser, one Nazi POW still secretly loyal

to Hitler, and the mission would unravel. In all likelihood, the OSS team led by

Aaron Bank would be executed on the spot.

Setting aside worry over the Hague resolution against treacherous killing,

Bill Casey was concerned about a certain rule of engagement (ROE) issued by

Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower, to whom he was

fiercely loyal. General Eisenhower had forbidden the U.S. Army and the OSS

from recruiting and hiring Nazi POWs for any kind of mission. Casey, skilled

lawyer that he was, appreciated loopholes. By encouraging the captured Nazis to

“volunteer” for the Iron Cross Mountain Infantry mission, he created a legal go-

around that allowed him to proceed.

As chief of OSS Special Operations in Europe, Bill Casey had authorized

dozens of teams air-dropped into this area. But he remained cautious about

inserting the Iron Cross Mountain Infantry, because he knew the area around

Eagle’s Nest to be heavily guarded by elite Nazi commandos. Still, Casey

authorized Bank to begin preparing the team and await further instructions.

At an undisclosed European location, Bank led commando training, teaching

Nazi turncoats new infiltration techniques, including how to extract individuals

from armored cars and how to storm a mock-up of the target. The plot advanced

to the point where Bank was given a large sum of cash with which to pay bribes,

and a small gold ring to barter for his freedom in the event he was separated and

captured. Each OSS operator was given a cyanide capsule, as Jan Kubiš and

Josef Gabčík had been.

The prospect of killing Adolf Hitler caused Aaron Bank to lie awake at night

thinking “wild thoughts, world shattering in scope,” he later wrote. If Bank’s

OSS team succeeded in killing Adolf Hitler it would be the end of the war,

because the German General Staff would surely surrender. With no one left to

command the army, wrote Bank, “This would be the only time in [history] that

five guys would be responsible for ending a major war.”

Bank continued to train the Iron Cross Mountain Infantry. He and his men

conducted a dangerous dry run over the drop zone, practicing reconnaissance

and exfiltration techniques. Then he waited. And waited. The anticipation was

excruciating. Storms hung over the Alps, first for days, then weeks. It was April

1945. Finally, Aaron Bank was flown to Supreme Headquarters Allied

Expeditionary Force, in Paris, for a classified briefing with General Eisenhower.

The U.S. Army had moved infantry soldiers into the Inn Valley. There were

boots on the ground now, closing in around Eagle’s Nest. Operation Iron Cross

was canceled. Bank was devastated. To kill or capture Hitler was the opportunity

of a lifetime. In a flash, it was gone.

On May 7, 1945, the Nazis surrendered at a brief ceremony inside a

schoolhouse in Reims, France. General Walter Bedell Smith, Eisenhower’s chief

of staff, officiated the historic end of the Third Reich. Three months later, after

the United States dropped two atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki,

Imperial Japan surrendered unconditionally to the Allies, ending World War II.

Six weeks later, on October 1, 1945, President Truman signed an order

abolishing the OSS. Truman disliked William Donovan and his band of

ungentlemanly warriors. In a curt memorandum, the president thanked Donovan

for his service and wished him well. To President Truman’s eye, America was

the new standard-bearer of democratic ideals. The U.S. military was the

mightiest in the world. Soldiers of a democracy do not fight guerrilla wars.

Gentlemen do not slit throats.

In Bastrop, Texas, Billy Waugh took part in every victory parade. He’d stand on

the corner when the parade began, waving his flag at the war heroes. Then he’d

duck away from the crowds, race through an alleyway, and get back to the street,

in advance of the marching men. He’d repeat this action all morning or afternoon

until the parade ended. Two local marines wounded in the war were especially

interesting to him. One had a wound to the head and the other wore a cast on his

leg.

“Whenever I was near them,” remembers Waugh, “in a street or a store, I felt

awed to be in their presence. I admired their strength and nobility.”

One month after graduating from high school, Billy Waugh joined the U.S.

Army as a paratrooper. He was off to Fort Benning, in Georgia, to learn how to

jump out of airplanes. His whole life was in front of him and it felt great.

2

Tertia Optio

Six months passed. One night in April 1946, America’s ambassador to the

Soviet Union, General Walter Bedell Smith, was riding in his chauffeur-driven

limousine headed to the Kremlin, where he was set to meet with Josef Stalin.

Tempered yet tenacious, the former general was a man well versed in military

operations. During the war, Bedell Smith served as Eisenhower’s chief of staff.

Wartime colleagues called him “Ike’s hatchet man.” General Eisenhower called

him “the greatest general manager of the war.” An all-around intimidating

figure, Bedell Smith was rarely one to express unease, and yet here he was,

feeling apprehensive about what lay ahead. He served as President Truman’s top

diplomat now, and the issue at hand was how not to go to war with the Soviet

Union.

“I believed myself more or less immune to excitement, but I must confess I

experienced a feeling of tension as the hour for the interview approached,”

Bedell Smith later recalled. “I thought the meeting might be a stormy one.”

World War II had been over for less than a year, and already Stalin was the new

nemesis of the Western world.

Stalin was paranoid and power-mad. As premier of the Soviet Union, he

ruled by terror. Since his rise to power in the early 1920s, he’d starved and killed

millions of his own people and personally oversaw the assassination of rivals

who threatened him, including Leon Trotsky, an early architect of the Soviet

state, whom he had ordered to be killed in Coyoacán, Mexico, in 1940. Stalin

assassinated writers and philosophers unwilling to peddle propaganda, and

scientists and engineers who failed to solve his technology problems. In 1937, he

had eight of his top army generals executed in the Great Purge. During World

War II, he had been one of America’s most powerful allies, which made it

necessary to look beyond his crimes and win the war. Now, from the perspective

of the State Department officials to whom Walter Bedell Smith reported, Josef

Stalin was no longer behaving as a friend.

The U.S. embassy car moved quickly down Arbat Street through the sootstained snow, the American flags attached to its antennae whipping in the night

air. This route to the Kremlin was along one of the most heavily policed streets

in the world, but because the car’s occupants enjoyed diplomatic privileges, it

never had to stop; all the traffic lights remained green as Bedell Smith’s driver

hurtled along.

Sitting alone in the backseat, the ambassador read and reread pages of notes prepared for him by the State Department. “Possible Points to Be Stressed in Conversation with Stalin,” its header read. Just a few days prior, Bedell Smith’s chargé d’affaires at the embassy in Moscow, a career diplomat named George Kennan, had advised President Truman on the threat posed by Stalin, in what would become known as the Long Telegram. Stalin knew only the “logic of force,” Kennan said. The Soviets were on the move, devouring territory around the globe. The United States had only one option. Stalin had to be stopped.

Bedell Smith’s mission was to find out how much more land Stalin intended to grab. To look at a map made the problem self-evident. Russia’s human losses in World War II had been colossal, with some twenty million dead. But more troubling for the West were its territorial gains. During the war, Stalin’s Red Army took possession of almost half of Europe, then kept much of it after the Nazis capitulated. In 1946, power came in numbers; military strength was still about a nation’s potential army size. The U.S. population was around 140 million. Stalin ruled over 200 million Russians and another 100 million people living beyond the country’s traditional borders in the land that had been grabbed. To make matters even more threatening, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was getting bigger by the season. The question Bedell Smith needed answered was simple but uncomfortable: How much further was Stalin going to go?

The embassy car deposited Bedell Smith at the Kremlin’s main gate, and the ambassador was taken inside to Stalin’s personal office building. Bedell Smith was escorted up to the third floor, down a long, austere corridor, and into a high ceilinged, wood-paneled conference room. There sat Stalin, his back to the wall, facing Bedell Smith as he entered. Behind the dictator hung massive oil portraits depicting the great Russian marshals, most of them on horseback. Bedell Smith spotted Suvorov and Kutuzov, “two military strategists noted for their expansionist views.”

Once seated, Bedell Smith spoke first, through an interpreter. He discussed the most pressing issues from his State Department notes, watching Stalin as he took exaggerated draws on a long, thin cigarette. By the time Bedell Smith finished talking, Stalin had picked up a red pencil and begun writing—points to later debate, Bedell Smith first assumed. But upon closer inspection, it was clear that Josef Stalin was doodling. The ambassador was stunned. “His drawings, repeated many times, looked to me like lopsided hearts done in red, with a small question mark in the middle.” Stalin entered the conversation by making a point about oil. Iranian oil.

“You don’t understand our situation with regards to oil and Iran,” Stalin said, suggesting that he could answer the ambassador’s questions with a singularly cryptic point. “The Baku oil fields are our major source of supply. We are not going to risk our oil supply.” The Soviet Union needed a greater share in the exploitation of the world’s oil, Stalin said, and the competition for these resources was a significant point of contention between Russia and the United States. As Bedell Smith considered his response, Stalin took the opportunity to bring up a more personal matter. Lately, Great Britain and the United States had been “teaming up against Russia and placing obstacles in her path,” Stalin said.

Bedell Smith was caught off guard. Did Stalin “really believe that the United States and Great Britain are united in an alliance to thwart Russia?” he asked.

“Da,” Stalin replied in a long, slow breath. Yes.

“I must affirm in the strongest possible terms, that is not the case,” the U.S. ambassador insisted.

Except it was true. British prime minister Churchill had stated as much just one month before, during a speech at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri. “An iron curtain has descended across the European Continent,” Churchill famously declared. “From Warsaw to Berlin… all these famous cities, and the populations around them, lie in what I must call the Soviet sphere, and all are subject in one form or another not only to Soviet influence but to a very high and, in many cases, increasing measure of control from Moscow.” Churchill had compared Stalin to a puppet master. This infuriated Stalin. Like most tyrants, he resented any person who suggested that his popularity was based not on adoration but fear.

Stalin had hated Churchill for decades. “In 1919… Churchill tried to instigate war against Russia, and persuaded the United States to join him in an armed occupation against parts of our territory,” Stalin reminded Ambassador Bedell Smith, adding, “Lately he’s been at it again.” Stalin called the Westminster speech “an unfriendly act,” and said that it was “an unwarranted attack upon the U.S.S.R.” He pointed out that the United States would never stand by passively if such an insult was hurled in its direction. “But Russia, as the events of the past few years have proved, is not stupid,” Stalin forewarned. “We can recognize our friends from our potential enemies.”

Ambassador Bedell Smith was in a bind. He needed an answer for President Truman, so he asked Stalin directly, “How far is Russia going to go?”

Stalin paused. Stopped doodling the red hearts and the question marks. Looking directly at Walter Bedell Smith, he replied in a monotone, “We’re not going to go much further.”

But what, exactly, did “much further” mean? That was the enigma of 1946. Stalin ended the interview and the ambassador was shown the door.

Eleven months later the United States drew a line in the sand, declaring communism the enemy of democracy. On March 12, 1947, in a dramatic speech to a joint session of Congress, President Truman warned the American people that Moscow had to be stopped. “It must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation,” Truman said. Without American help, darkness and cataclysm would descend in the world, and “disorder might well spread throughout the entire Middle East.” In a display of near-unanimous support, the members of Congress took to their feet. For two minutes President Truman enjoyed his first standing ovation since the end of the war. The speech marked the beginning of the Truman Doctrine, American foreign policy designed to confront and counter Soviet geopolitical expansion.

Congress passed the National Security Act of 1947, restructuring the U.S. military and intelligence agencies and creating a national-security apparatus for the modern era. The act officially established the Central Intelligence Agency and the White House National Security Council (NSC). And it gave way to an unconventional-warfare division for the president to command, on his authority and his alone. This unit was designed to be covert. George Kennan called it a guerrilla warfare corps for the commander in chief. Covert action would become the president’s hidden hand, visible only to those in his inner circle.

The National Security Council directed the CIA to take control of these hidden-hand operations, officially called covert-action operations, under Title 50 authority of the U.S. Code. The Department of Defense would work under a separate authority called Title 10, which outlines the role of the armed forces. This distinction remains in effect today.

During a National Security Council meeting in December of 1947, the president’s advisors clarified that the CIA’s covert-action authority would include “preventative direct action through paramilitary activities” as a means of countering “the vicious covert activities of the USSR.” “Direct action” would become a key phrase at the CIA, one that allowed its officers and operators Title 50 authority not available to anyone else in the United States unless expressly directed by the president.

The CIA’s general counsel, Lawrence Houston, requested clarification. How much autonomy would the CIA have in conducting these covert-action operations? “Lack of such specific direction may be considered a weakness in the National Security Act of 1947 that deserves further consideration by the Congress,” Houston wrote. The following month, National Security Council Directive 10/2 (NSC 10/2) provided the clarification Houston had sought. A new office was to be created inside the CIA, called the Office of Special Projects, where covert actions would be planned and executed in peacetime. In times of war, the CIA was to coordinate its covert operations with the Defense Department and the Joint Chiefs of Staff. “‘Covert operations’ are understood to be all activities… which are conducted or sponsored by this Government against hostile foreign states or groups,” according to the directive, “… but which are so planned and executed that if uncovered, the U.S. Government can plausibly disclaim any responsibility for them.” While the concept of willful ignorance has insulated countless commanders and kings from embarrassment and scandal, it was in this moment that the president’s National Security Council made the concept of plausible deniability an official construct. Plausible deniability would hereafter allow U.S. presidents to say they didn’t know.

For the first time in American history, the president had at his disposal a secret paramilitary organization, authorized by Congress, to carry out hidden hand operations to protect U.S. national-security interests around the world. Before NSC 10/2, there were two ways in which U.S. foreign policy and national security were pursued. The first option was diplomacy; the second, war. Covert action was now the president’s third option, or Tertia Optio, after diplomacy failed and a Title 10 military operation was deemed unwise. On September 1, 1948, the Office of Special Projects changed its name to the more innocuous sounding Office of Policy Coordination (OPC) and got to work. “The new organization’s activities might well enhance possibilities for achieving American objectives by means short of war,” said George Kennan, co-architect of NSC 10/2 along with James Forrestal, the nation’s first secretary of defense. According to a report written by the National Security Council, kept classified for fifty-five years, the CIA’s Office of Policy Coordination would now be responsible for covert-action paramilitary operations including “guerrilla movements… underground armies… sabotage and assassination.”

In its first two years of existence, the CIA’s covert operations concentrated on anticommunist partisan groups in Europe and the Eastern bloc. Then, on June 25, 1950, the unthinkable happened. The army of North Korea, backed by Soviet tanks and Chinese intelligence, invaded South Korea, with the goal of reuniting the divided country under communist rule.

The entire Western world was caught off guard. The CIA had failed to foresee an attack that the U.S. national-security apparatus feared could be the opening salvo of World War III. The United Nations called upon the invading communist troops to cease fighting and withdraw to the 38th parallel. When the invaders refused, the UN Security Council looked to its members for help. “I have ordered United States Air and Sea forces to give the Korean government troops cover and support,” President Truman announced from the White House press room. After just five years of peace, the country was at war again. Behind-the lines paramilitary operations were needed to augment conventional forces. The CIA surged ahead with plans to take the lead.

With a formidable figure now at the helm, the CIA’s credibility and access to resources dramatically expanded. According to CIA documents kept classified for nearly fifty years, “Korea became a testing ground for the support of conventional warfare with unconventional efforts,” or black operations behind enemy lines. Walter Bedell Smith had no experience in covert operations, so he looked to outside experts. He chose them unwisely, he later learned.

With black operations now at the fore, the CIA called upon the experience and talents of the Office of Strategic Services, dismantled by Truman in October 1945. Its members had hardly disappeared from public service. At the start of the Korean War, one-third of the CIA’s total personnel had previously served in the OSS. “I know nothing about this business,” Bedell Smith confided to Admiral Sidney Souers, the CIA’s first director. “I need a Deputy who does.” For the job of deputy director of plans, a euphemism for director of covert operations, he chose veteran OSS officer and future CIA director Allen Dulles. In turn, Dulles filled the positions below him with veterans of the OSS.

Frank Wisner, formerly the OSS station chief in Romania, assumed responsibility for Office of Policy Coordination operations and staff. Wisner, or “Wiz,” as he was known among colleagues, was a complex individual, obsessed with rolling back Soviet gains. A former Olympic runner, he was now overweight and out of shape from years of heavy drinking and womanizing. He was under pressure from the FBI for having had a wartime affair with a Romanian princess suspected of being a Soviet spy. His mercurial behavior was written off by colleagues and family alike as part of his personality. “He seemed to be only half with us, always pondering some insoluble riddle,” said his son Graham. “Nevertheless, he dominated every conversation with an extraordinary mixture of wit, charm, humor, and southern power.” What no one knew at the time was that Frank Wisner was in the early stages of mental illness and would eventually end his own life with a shotgun blast in the mouth. For now, he was in charge of planning and overseeing paramilitary action in Korea, sending hundreds, perhaps thousands, of good men to their deaths. The black mark he left on the Agency still haunts the CIA today.

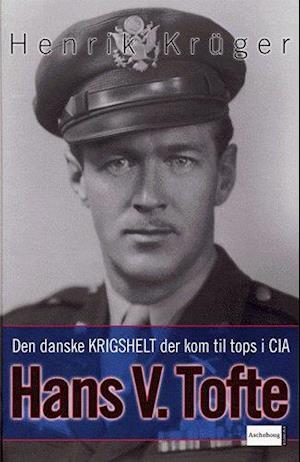

Walter Bedell Smith mistrusted Frank Wisner, but he was stuck with him. In Korea, Wisner and his team began planning covert-action operations. One of the first was an operation to infiltrate an agent into Pyongyang to assassinate North Korea’s communist dictator, Kim Il Sung. The operation was so sensitive it was personally handled by Wisner’s deputy chief of CIA covert operations, a former OSS officer named Hans V. Tofte.

The enigmatic Hans Tofte was an American citizen born in Denmark. At first

glance, he appeared highly qualified for the job. Fluent in Japanese, Russian, and

Chinese, he had lived overseas in his twenties and been recruited by the British

Secret Intelligence Services in the early years of the war. When the OSS was

created, Tofte was assigned to its Special Operations division. He had trained

Jedburgh candidates Bill Casey and Aaron Bank in guerrilla warfare at Area B.

Inserted into the war theater by parachute, he fought the Nazis behind enemy

lines, in Italy and Yugoslavia, with valor. The king of Denmark knighted him.

But like Frank Wisner, something had happened to Hans Tofte in the five years

since the end of World War II. His character transformed. By 1950, Tofte was a

liar and a thief. Was it post-traumatic stress? Hubris? Too much booze? The

danger of covert-action operations, and the plausible deniability construct in

which they exist, was that it made it possible for ignoble actions to be easily

concealed.

The enigmatic Hans Tofte was an American citizen born in Denmark. At first

glance, he appeared highly qualified for the job. Fluent in Japanese, Russian, and

Chinese, he had lived overseas in his twenties and been recruited by the British

Secret Intelligence Services in the early years of the war. When the OSS was

created, Tofte was assigned to its Special Operations division. He had trained

Jedburgh candidates Bill Casey and Aaron Bank in guerrilla warfare at Area B.

Inserted into the war theater by parachute, he fought the Nazis behind enemy

lines, in Italy and Yugoslavia, with valor. The king of Denmark knighted him.

But like Frank Wisner, something had happened to Hans Tofte in the five years

since the end of World War II. His character transformed. By 1950, Tofte was a

liar and a thief. Was it post-traumatic stress? Hubris? Too much booze? The

danger of covert-action operations, and the plausible deniability construct in

which they exist, was that it made it possible for ignoble actions to be easily

concealed.

Like Frank Wisner, Tofte would ultimately experience a tragic downfall. Fired from the CIA for stealing classified information, he would die impoverished, his reputation in ruins. But for now, as deputy chief of CIA covert operations in Korea, Tofte was in charge of running the assassination plot to kill Korean president Kim Il Sung. To do this, he oversaw six CIA operators who worked out of a hotel room in Tokyo.

There were classified reasons why the CIA feared Kim Il Sung. To the intelligence community, he was the most dangerous kind of despot, a Soviet puppet. The CIA believed Kim Il Sung to be a “top-ranking traitor who isn’t even who he said he [is],” according to a dossier entitled “The Identity of Kim Il Sung.” The man’s real name was Kim Sung-ju, analysts concluded. Orphaned as a child, he was said to have “killed a fellow student” while in high school. The circumstances of the murder were chronicled in his CIA file: “Needing money, he stole it from [a] classmate, was caught, [and] fearing possible disclosure, killed his classmate,” the dossier read. It was around this time that the orphan Kim Sung-ju was identified by communist intelligence agents as someone the party could blackmail into use.

The real Kim Il Sung had been a genuine war hero, a courageous guerrilla fighter who’d battled Japanese invaders in the Paektu Mountain region of Korea during World War II. According to information in the CIA dossier, Stalin’s assassins killed the war hero and “disappeared him.” This enabled Stalin’s minions to steal the war hero’s identity and give it to the orphan boy, with a caveat. The impostor? Kim Il Sung would now act as Moscow’s puppet.

In the fall of 1945, when Stalin appointed a man named Kim Il Sung to be secretary general of the North Korea Communist Party, the identity theft was complete. “Specific instructions [were] given to the leaders of that regime that there should be no questions raised about Kim Il Sung’s identity,” the CIA learned. If the story were indeed true, North Korea’s new leader was an exceptionally dangerous kind of tyrant, fundamentally beholden to the Kremlin. If Kim Il Sung did not do exactly as instructed by the Politburo, his background as a murderous orphan, not a war hero, could be revealed.

North Korea was one of the poorest countries in the world, and Kim Il Sung was dependent upon Russian patronage for his country’s most basic needs. Everything he did was now in service to his communist masters, including the siege and subsequent land grab of South Korea. The CIA’s Office of Policy Coordination put North Korean president Kim Il Sung at the top of one of its earliest known targeted kill lists.

Hans Tofte received a cable from Washington. An assassin had been chosen for the job. Tofte was to receive the CIA covert-action operator in Tokyo, then oversee his infiltration into Pyongyang. “The man [was] a Cherokee Indian code-named Buffalo,” Tofte told historian Joseph Goulden after the war. As had Reinhard Heydrich’s assassins, Jan Kubiš and Josef Gabčík, Buffalo had volunteered for the job. “He’d been asked in Washington, ‘How would you like to kill Kim Il Sung?’ And he had accepted the mission with great pride,” Tofte recalled.

Tofte received instructions to meet the assassin “near the wall of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo, at sunset” at a designated time, on a specific day. Carrying a briefcase full of cash from his office’s unvouchered funding authority, Tofte handed over “a considerable amount of money” to Buffalo, he later recalled. The mission failed, he says, and Buffalo was never heard from again.

The idea that a Native American Indian, an assassin for the CIA, could simply make his way to Pyongyang in the middle of a war and blend in among the locals there was ambitious and foolhardy. It also set a precedent for what would eventually become known as lethal direct action—targeted killing— directed against a specific person either in peacetime or war. While the Hague resolution prohibited assassination, Title 50 covert-action authority made targeted killing legal, intended to counter “the vicious covert activities of the USSR.” The fabricated identity of Kim Il Sung was a case in point, a Soviet covert act of deception directed against the United States. Through North Korea’s supreme commander, Stalin could entangle the United States in a war on the Korean Peninsula.

The Office of Policy Coordination began inserting CIA paramilitary teams deep inside Korea, behind enemy lines. The teams, led by Americans and made up of anticommunist Korean and Chinese nationals, were air-dropped into hostile territory to conduct sabotage and subversion, including hit-and-run assassinations, similar to what the OSS had done during World War II. The results were disastrous, as explained by the man assigned to lead the CIA’s parachute infiltration efforts, a former OSS Jedburgh named John “Jack” Singlaub. In 2016, Singlaub, ninety-six, recalled these wartime tragedies with clarity and stoicism.

“One of the impossible imperatives of war in Asia was that Westerners could never simply disappear behind enemy lines into the civilian populations as we had done in Nazi-occupied Europe,” Singlaub said. “This was a tremendous challenge in Korea and an equally difficult problem in Vietnam.” He was referring to the future war in which he would also play a significant role, running covert-action operations for the CIA. Singlaub would rise to the position of U.S. Army major general.

In 1951, Jack Singlaub served as CIA deputy chief of station in Seoul. He and his colleagues worked out of the newly renovated Traymore Hotel downtown. Their cover was that they were with an advisory organization called the Special Operations Group (SOG), Joint Advisory Commission, Korea (JACK), 8132nd Army Unit. The cover name paid homage to the OSS Special Operations Branch, and the unit became known simply as JACK. JACK’s first commander, Singlaub’s boss, was the CIA’s chief of station in Seoul, Ben Vandervoort, a legendary paratroop commander who’d lost one eye fighting Nazis in Holland. A month after Singlaub arrived, Vandervoort was called back to Washington, much to Singlaub’s dismay. His replacement was a former CIA operative and army colonel named Albert R. Haney, a man whose integrity would also come under fire, as had Wisner’s and Tofte’s.

Following a blueprint created by the OSS, the CIA’s Office of Policy Coordination sought to organize an anticommunist guerrilla force it could train and equip for partisan warfare behind enemy lines in Korea. OPC officers combed through refugee camps in South Korea looking for local fighters qualified for paramilitary service, including North Korean and Chinese nationals. Back in America, dozens of college graduates were being recruited by the CIA to lead these covert-action operations in the Far East. One of the young recruits was Donald P. Gregg, who was studying cryptanalysis—the study of hidden information systems—at a liberal arts college in Massachusetts. Gregg would eventually work for the CIA for thirty-one years.

Gregg and dozens of other new officers-in-training were sent to a clandestine irregular-warfare facility run by the CIA on the island of Saipan, a tiny dot in the Pacific Ocean 2,000 miles southeast of Seoul. There, hundreds of young male Korean and Chinese refugees recruited from war camps underwent weeks of training in guerrilla warfare tactics. “We were following in the footsteps of the OSS,” says Gregg, who later became U.S. ambassador to South Korea.

But unlike veteran covert-action officer Jack Singlaub, Don Gregg had no experience fighting wars, let alone using unconventional-warfare tactics behind enemy lines. He’d only recently graduated from Williams College and barely knew where Korea was on the map. “We didn’t know what we were doing,” he says of his experiences on Saipan. “I asked my superiors what the mission was but they wouldn’t tell me. They didn’t know. We were training Koreans and Chinese and a lot of strange people,” Gregg recalled. The problem facing the CIA in Korea was twofold: Who exactly were the indigenous forces the Agency was training, and could it be assumed that they, too, were in pursuit of American goals? A great majority spoke no English. An equal number were illiterate. How could the CIA identify a traitor under such circumstances? How would anyone know if a recruit or volunteer was in fact a spy sent by the North Korean People’s Army or the Internal Security Forces?

Jack Singlaub had his own set of worries, more practical than theoretical. His OPC colleagues Frank Wisner and Hans Tofte were anxious to begin airdropping teams of CIA operators and their local forces into North Korea, behind enemy lines. As the man overseeing air-insertion tactics, Singlaub felt this pressure. He also worried about getting the men safely into the war zone. “The Chinese were well aware of our airdrop operations and had learned to recognize [the sound] of low-flying transport planes that had an open door,” he recalls. Singlaub felt it would be safer to air-drop the operators into enemy territory from higher up. This would give them a greater chance of successful clandestine insertion, he believed.

CIA covert-action operations were being run out of a forward operating base (FOB) on Yong-do Island in southwestern Korea, and it was there that Singlaub began testing his new idea. “Parachuting was my specialty from the OSS Jedburgh days,” he recalls. He borrowed a B-26 light bomber aircraft from the air force, rerigged the bomb bay as a jump platform, and went out for a test. “I told the pilot to keep his airspeed close to normal for level flight, then jumped assuming the same position I’d used to jump into Nazi-occupied France.” Once he was out of the aircraft, he pulled his parachute and floated down to the ground. “The test demonstrated we could use bombers for agent drops,” he says. The success sparked another idea, a way to get a team in even more secretly. What if, he thought, instead of pulling his rip cord right away, he instead allowed his body to fall through the air, reaching terminal velocity—roughly 122 mph or 54 meters per second—and then pull? This was long before the days of skydiving, back when “the military had very clear protocols about how its paratroopers jumped,” Singlaub clarifies. What he wanted to do now was freefall, then pull his rip cord, say, one thousand feet above the ground. While inherently more dangerous than a static line jump, free-falling meant the enemy was less likely to see an agent’s parachute as he floated to earth.

To test this idea, Singlaub borrowed an L-19 Bird Dog from the air force. Accompanied by airborne specialist Captain John “Skip” Sadler, he made a series of test jumps, leaping out of the aircraft and having Sadler record the time before his parachute blossomed. After each test, Singlaub waited longer on the next jump, thereby getting closer to the ground each successive time. “Objects on the ground came into sharp focus within a thousand or so feet. I watched an object on the road below change from a blurred dot to what looked like a child’s toy, to an actual U.S. Army jeep with a white star stenciled on its hood. I pulled the rip cord.” Singlaub’s parachute opened and his feet hit the sand. “Neither of us realized at the time that we’d invented the concept of high-altitude low opening (HALO) parachute drops, right there over the Han River in Korea.” The HALO jump has since become the most effective means of inserting covertaction operators into denied territory and behind enemy lines. In 2019, it is still the method of choice.

In Washington, DC, a battle over covert-action operations was under way between the CIA and the U.S. Army. When war broke out on the Korean Peninsula, there was no special operations forces (SOF) capability at the Defense Department. “The military response was hesitant, skeptical, indifferent, and even antagonistic” with regard to all aspects of unconventional, or irregular, warfare, says retired colonel and U.S. Army historian Alfred H. Paddock Jr. Most military leaders at the Pentagon wanted no part of these ungentlemanly black operations. “Guerrilla warfare was frowned upon,” says Singlaub.

There were two notable exceptions. Leading a small group of guerrilla warfare pioneers inside the military establishment in 1951 were General Robert A. McClure, former director of the Psychological Warfare Division during World War II, and Colonel Russell W. Volckmann, a former U.S. Army captain who’d led the only non-OSS guerrilla operations during the war, in the Philippines. What gave General McClure and Colonel Volckmann momentum in their efforts was that both men had the ear of their former boss, General Eisenhower, now serving as the U.S. Army chief of staff.

As per National Security Council Directive 10/2, covert action was to be the sole responsibility of the CIA during peacetime. Korea was different. This was war, McClure and Volckmann agreed. “To me, the military has the inherent responsibility [in] time of war to organize and conduct special forces operations,” Volckmann told his commanding general. “I feel that it is unsound, dangerous, and unworkable to delegate these responsibilities to a civil agency”—that is, the CIA. General McClure took a similar position. “I believe the Army should be the Executive Agent for guerrilla activities,” he told the army chief of staff. “I am not going to fight with CIA as to their responsibilities in those fields.”

In an attempt to alleviate the conflict, the Joint Chiefs of Staff created an army organization to work with JACK, called CCRAK (pronounced “seacrack”). In CCRAK documents located in the National Archives, the organization’s original acronym is revealed: Covert, Clandestine and Related Activities in Korea, an on-the-nose description of the U.S. Army’s secret guerrilla warfare unit in Korea. As happened at the CIA, the name was quickly changed to something more innocuous. CCRAK became Combined Command Reconnaissance Activities, Korea. An operations base was set up on Baengnyeong Island, off the coast of South Korea, near the Northern Limit Line. The unit assigned to work with the CIA’s JACK was originally called the Guerrilla Section, 8th Army Miscellaneous, but this name was also deemed too revealing; it was changed to the United Nations Partisan Infantry Korea (UNPIK).

That the army was vying for power over covert operations infuriated the CIA’s Frank Wisner. The CIA informed the Department of Defense of its displeasure. “Mr. Wisner, as head of OPC, would like it to be clearly understood that this understanding is reached on the assumption that the Army is creating a Special Forces Training Command for its own purposes and not at the request of CIA,” Agency officials wrote, in a now declassified memo. Theirs was a temporary wartime gesture of cooperation. “The CIA [is] not going to place itself in the position of giving the Army an excuse to justify the creation of its own unconventional warfare capability.” Once the war was over, Agency officials demanded that covert-action authority be returned to the CIA.

The aversion to risk was perhaps the single greatest discrepancy between the CIA and the Pentagon. The CIA was about taking chances. Its officers and operators were trained to act as the president’s hidden hand. Covert-action operations are meant to remain forever hidden from public scrutiny. In the event one becomes known, plausible deniability becomes the goal. At the opposite end of the spectrum is the U.S. military, an organization that follows strict procedures and protocols. Its classified and clandestine operations might be kept secret for a period of time, but eventually they are meant to be revealed. “One of the biggest obstacles I faced in Korea,” says Singlaub, “was the Pentagon’s worry that these [paramilitary] units might be captured, broken by physical and psychological torture, and turned against us for propaganda purposes.” Unlike CIA officers, the Pentagon’s soldiers are not explicitly trained how to lie.

JACK and CCRAK’s guiding principals were, however, ultimately the same. Each organization was born of the OSS, with foundations in guerrilla warfare. A manual entitled “Psy War 040 CIA” was given to both sets of operators to study and learn from. “Hit and run; these are the guerilla’s [sic] tactics,” its authors explained. “Primary objective; the killing and capture of personnel… sniping and demolitions. Initiative and aggressiveness tempered by calm judgement will be encouraged. Avoid trying to win the war by yourself.”

Colonel Douglas C. Dillard, a twenty-six-year-old infantry officer from Georgia, was put in charge of delivery and resupply of these joint CIA-army airborne operations, code-named AVIARY. The missions were kept classified until 2009. Although some took place early in the Korean War, the scale of operations rose dramatically starting in February of 1952. “One of AVIARY’s first missions ended in disaster,” Colonel Dillard recalled in 2009.

It was the winter of 1952, a period of time known as the Second Korean Winter, now twenty months into the war. A dismal lull had settled over the battlefield, with fighting diminished to violent, small-unit clashes and struggles over key outpost positions along the front lines of Korea’s hilly landscape. Hundreds of Americans had been captured and were being kept under brutal conditions inside POW camps. The joint CIA-army mission on the night of February 18, 1952, was designed to air-drop paramilitary operators who would gather reconnaissance on a POW camp and then exfiltrate by ground.

The missions were dangerous. Territory above the 38th parallel was notoriously inhospitable. Unlike with the OSS Jedburgh airdrops into France, there’d be a very limited greeting party on the ground, maybe one or two anticommunist partisan agents. Radio communication did not exist in the outer reaches of this landscape, so agents were dropped in with homing pigeons strapped to their legs. This was often their only means of communicating with their CIA and U.S. Army handlers in the south: a single homing pigeon to let the handler know they’d made it safely in. “The rate of return was incredibly low,” recalls CIA historian John P. Finnegan.

New tradecraft techniques were constantly being developed and tested. On this mission the covert-action operators wore enemy uniforms and carried Chinese-made weapons. “They could impersonate enemy patrols and, if necessary, shoot their way back to UN lines,” Dillard explained. But there was a much bigger problem facing the unit. “One everyone knew about and few wanted to discuss,” says Singlaub. “How do you trust that the indigenous agents you are paying will not try and kill you?” A traitor in the ranks almost certainly meant death.

It was the early morning hours of February 19, 1952, and air force captain Lawrence E. Burger was piloting a C-47, south of Wonsan, North Korea. There were two missions on deck, both covert-action operations, both parachute infiltrations of American, Korean, and Chinese national paramilitary teams behind enemy lines. Given the limits on usable aircraft, it was common to run more than one mission per flight. Master Sergeant Davis T. Harrison stood in the door with the four anticommunist Chinese agents he was running, preparing them for a static line jump. The partisans had been culled from a refugee camp down south and trained for action by CIA paramilitary officers. They all stood in the doorway ready to jump.