EXTREME PREJUDICE:

THE TERRIFYING STORY OF

THE PATRIOT ACT & THE

COVER UPS OF 911 AND IRAQ

BY SUSAN LINDAUER

CHAPTER 5:

IRAQ’S

PEACE

OVERTURES

TO

EUROPE

AND THE

UNITED

STATES

“The first casualty, when

war comes, is Truth.”

U.S. Senator

Hiram

Warren Johnson, 1918

In such a radically

changing political climate,

the CIA could not stay

passive.

Simply put, the status

quo had to change. With

pressure building from the

international community to

force a change, the CIA recognized it would have to

adapt in order to retain

control of the outcome, and

secure the most favorable

benefits for Washington.

Warming relations

between Iraq, Europe,

Russia and Asia wasn’t the

only “bad news” for Pro War

Republicans in the

months before 9/11.

Woefully for the War

Camp, Baghdad was locked

in a highly successful, two prong

strategy to undercut

whatever international

support for sanctions

remained. The Iraqi Government aggressively

courted foreign corporations

to visit Baghdad, and

publicly rewarded trade

missions with highly

lucrative reconstruction

contracts in any post sanctions

period.

That created a

secondary concern with

regards to future oil rights

in Iraq. U.S. demand for

Iraqi oil, and its avaricious

desire for future exploration

and development contracts

continued unabated, despite

U.S. hostilities to Saddam’s

government. U.S. refineries proved to be Iraq’s best

customers from the late

1990's onward, importing

750,000 barrels per day, or 9

percent of total U.S.

imports.

113 Chevron,

Exxon-Mobil, Bayoil and

Koch Petroleum ran the

most Iraqi oil through their

refineries.

If the U.S. was Iraq’s

most loyal customer, for

obvious reasons it was not

Iraq’s favorite customer.

Iraq made a practice of

rewarding friendly nations

that opposed sanctions with

major oil exploration and development contracts that

would become active in any

post-sanctions period.

Among those allies, Russia

stood out. Baghdad gave

favored status to Russian

shipping and trading firms,

“taking large volumes of

crude…. away from

previous customers.”

114

Thus, as Russia

confronted its own critical

period of economic

upheaval, it emerged as

Iraq’s largest trading

partner, winning 40 percent

of all oil export contracts

under the “oil-for-food” program. The transfer of

contracts to Russian oil

traders was widely regarded

as payback for Moscow’s

refusal to allow Washington

and London to revise

sanctions in the Security

Council, as opposed to

ending them outright.

President Vladimir Putin

declared a strong desire for

close bilateral relations with

Baghdad.

Most significantly, Iraq

awarded a highly lucrative

contract to LUKoil, Russia’s

premiere oil corporation.

The 1997 LUKoil contract to develop the West Qurna

field, expected to produce

600,000 barrels per day, was

the largest deal signed by

any international oil

company under Saddam’s

government.

115 Oil rights

carried an estimated value

of $20 billion for LUKoil,

with 3 percent ownership by

the Russian government.

Mega U.S. Oil

Corporations shuddered in

dismay when the LUKoil

contract was announced.

Even promises that U.S.

corporations could compete

for second and third tier sub-contracts for

development of the West

Qurna field could not alter

the blow that Russia’s

priority status would cause

for U.S. shareholders. It

locked into place a structure

for oil rights in Iraq that

would seriously crimp the

long term earning potential

of politically connected

corporations like

Halliburton and Chevron

Texaco, which had been

eyeing Iraq’s oil potential

for a decade. LUKoil

agitated Washington.

Contrary to rhetoric in the European media,

however, France, Russia and

China weren’t the only

recipients of bountiful

reconstruction contracts. A

substantial offering was

made covertly to the United

States, as well.

And the CIA was

determined to drive a hard

bargain.

As early as October

2000, Iraq signaled a desire

to negotiate a

“comprehensive resolution

to its conflict with the

United States that would be

mutually beneficial to both parties,

”

116

according to

U.N. Ambassador Saeed

Hasan.

Central to those

discussions, before back

channel talks kicked off,

Iraq agreed in principle to

accept the return of U.N.

weapons inspectors, a

ground-breaking shift in

Baghdad’s policy, and a

major break in the deadlock

over Iraq’s disarmament.

The CIA accepted the talks

with that understanding

upfront. Notably, Baghdad’s

acquiescence occurred fully

18 months before the world community learned of Iraq’s

commitment to resume

inspections.

To be fair, as of

November and December

2000, Baghdad hoped to

structure the new agreement

in such a way as to prevent

the belligerent and insulting

behavior practiced by

Richard Butler’s inspection

teams before the 1998

pullout.

117 At the start of

talks, Iraq wanted a

statement of intent that U.N.

inspectors would behave

with a modicum of respect

for their host, without racial slurs against Arab culture or

mockery of the suffering of

Iraq’s people, which was

endemic to the previous

inspections.

There was legitimate

basis for Baghdad’s

concern. I myself overheard

derogatory remarks about

the Iraqi people in the

United Nations cafeteria in

New York, of all places.

One such conversation

between U.S. and British

diplomats scorned the

deaths of Iraqi children, and

ended with laughter. So I

know racial insults were fairly common. Baghdad

demanded that UN

bureaucrats should behave

like professionals.

Above all, Iraq wanted

to establish a mechanism

for lifting the sanctions as

compliance moved forward,

so that any new round of

weapons inspections could

not continue indefinitely, as

before, without

acknowledging substantial

proof of Baghdad’s

cooperation and verification

of disarmament.

Over and over, Iraqi

diplomats fretted how the U.S. would respond when

they found no weapons of

mass destruction. How

could Iraq compel the

United Nations to accept the

evidence that there was no

weapon stocks left to

destroy? What would

happen next? How could

Iraq make sure the U.N.

would follow through to end

the sanctions?

There was so much

despair over those

questions, and so much

distrust, that I knew in my

heart no illegal weapons

would be found in Iraq. To lighten up the conversation,

I would tease diplomats that

Baghdad should buy

weapons from Iran

(formerly Iraq’s mortal

enemy), and import them

through Syria (another

mortal enemy). When the

weapons got to the Iraqi

border, the Foreign Ministry

should call a press

conference and officially

unveil them, with the

announcement that Baghdad

was turning them over to the

United Nations, because

weapons inspectors refused

to go away empty handed.

The Iraqis could say to the

United Nations— “Now you

have your weapons! We

have bought them especially

for you. Go away! And

leave us in peace!”

But it was actually a

very serious problem in the

structuring of sanctions

policy. Sanctions presumed

that at all times Iraq would

have illegal weapons that

should be turned over to the

United Nations. Once Iraq

stopped possessing weapons

— and thus stopped turning

them over to U.N.

inspections teams—Baghdad fell into a state of

Non-Compliance.

In a perverse twist,

Iraq’s inability to hand over

W.M.D's amounted to a

violation of the Security

Council Resolutions.

Nothing in sanctions policy

established procedures for

what to do next. Because of

the rigidity of the policy

design, the U.N.

bureaucracy could not

adjust to that shift in reality.

Suspiciously too, the

oversight of Iraqi affairs

had become a full scale

bureaucracy at the United Nations, with high profile

jobs and six figure salaries

in New York and Geneva.

The bureaucracy had a

competing purpose— to

protect its own job security.

U.N. bureaucrats had every

incentive to perpetuate

sanctions indefinitely.

It’s unforgivably

obscene, if you consider the

humanitarian purpose and

ideology of the United

Nations. But that’s how it

was done.

There was a second

problem. Like all sanctions

regimens, the nature of its rigidity eliminated any

possibility of quid pro quo

in talks. It forced an all or

nothing solution, blocking

intermediary steps that

ordinarily would have been

implemented to move out of

deadlock. Thus, unhappily,

the goal of resuming

weapons inspections struck

many diplomats as

impossible to achieve. Iraq

would have to forsake its

national pride to comply.

Meanwhile, the U.S.

demanded exceedingly

tough standards for access

and transparency, which Iraq complained was

burdensome beyond the

scope dictated by the

Security Council. At the end

of the day, very few world class

diplomats wanted to

stake their reputations to

resolve this headache for the

international community.

Just like negotiations

for the Lockerbie Trial, that

meant the field was wide

open for a third party back

channel to kick start the

process— if someone could

be found who was not

intimidated by impossible

constraints and overwhelming odds against

success.

As it happened, this was

just my cup of tea. I had

already run this obstacle

course in back-channel

negotiations for the

Lockerbie Trial. Persuading

Libya to hand over its two

men for Trial was

considered impossible, too,

for all the same reasons. So

I understood the

expectations—and my

limitations and boundaries.

We would get this process

unstuck, and solidify

Baghdad’s commitment to resume the weapons

inspections. Then the

preliminary agreement

would get handed back to

the United Nations, so that

legal staff could ratify the

agreement in technical

language.

The U.N. would claim

victory. Congress would

pontificate. And we would

watch our success from the

sidelines, while others

strutted on CNN and the

FOX News Channel. All of

my glory would go to others

— most of them ignorant of

how our process of conflict resolution actually worked.

Straight off Lockerbie, I

was genuinely enthusiastic

and eager to help,

nevertheless. I saw this as a

unique and precious

opportunity to contribute to

my values. I grieved for the

suffering of the Iraqi

people. And I was willing to

assume the political risk. I

was fully committed to

seeing it through to the end,

with the greatest hope that

Baghdad’s humanitarian

crisis would come to an end

once and for all

And so I grabbed the opportunity with a full

heart. I rolled up my sleeves

and got to work. I swore to

my CIA handler, Dr. Fuisz

that anything Washington

wanted from Baghdad, I

would make sure it got.

In fact, I was very well positioned

to carry this

project forward. As a longtime

Asset, I had fairly

unique access to Iraq’s

senior diplomats in New

York. And I had all the right

contacts on the Security

Council to help me, as well.

Of all the diplomats at

the United Nations whom I was privileged to meet, Dr.

Saeed Hasan, Iraq’s

Ambassador to the U.N.,

stood out as the most

courageous and highly

moral individual that I

encountered. Dr. Hasan was

fully dedicated at all times

to decision making that

would protect the future of

Iraq’s children.

Most importantly, by

this time, Dr. Hasan had

been stationed in New York

for seven years as Iraq’s

Ambassador and former

Deputy Ambassador. As

such, Dr. Hasan recognized the scope of commitments

necessary for Baghdad to

get out from under

sanctions. Critically, he

accepted the personal risk of

delivering that message to

Saddam Hussein, at a time

when the proposal to resume

inspections was still highly

controversial in Baghdad.

118

Ambassador Hasan

understood the greater issue

of disarmament for the

West. Yet he was fiercely

protective of Iraq’s

sovereignty. This solution to

this quagmire was only

possible because of Dr. Hasan. He broke the

deadlock.

In October, 2000, when

Iraq indicated it was ready

to discuss a “comprehensive

settlement on all

outstanding issues,

” Dr.

Hasan communicated that

offering through my back

channel to Dr. Fuisz and

Hoven. From them, it

reached the upper echelons

of CIA and other concerned

parties in the Intelligence

Community.

All agreed that after the

November, 2000

Presidential Election, I could take up the weapons

inspections with

Ambassador Hasan. My role

would be to persuade Iraq to

accept the rigorous demands

for compliance and

transparency dictated by the

United States. According to

CIA conditions, I would

have no part in determining

what those technical

standards should be. I would

push Iraq to accept U.S.

demands in all areas. I

would not criticize U.S.

demands publicly or in

private conversations. My

remarks would be limited to demanding that Iraq satisfy

Washington before

sanctions could be lifted.

Most critically, it would

be a fixed price. There

would be no haggling. The

U.S. would define the terms.

Iraq would have to agree

“with no conditions,

” on all

matters.

The CIA was hot for a

public victory. Most

critically, U.S. Intelligence

wanted to show its European

allies that Washington had

stolen back control of the

endgame. That marked a

huge success for the Americans. By usurping

control of the agenda for

ending sanctions, the CIA

could play both sides. The

CIA could force Iraq to

submit to disarmament

verification, while

preventing Baghdad from

punishing Washington for

the deaths of one million

Iraqi children under the age

of 5.

Weapons inspections

remained paramount; but

Iraq’s sweetheart deals in

Europe and Asia created a

new imperative that U.S.

Intelligence was determined to re-balance.

The CIA would move heaven and earth to protect market access for U.S. corporations in any post sanctions period.

And so, in November, 2000, while votes in Florida were still getting counted, I sat down with Dr. Hasan at the Ambassador’s House in New York to hold preliminary talks on resuming the weapons inspections.

The meetings in November and December, 2000 culminated in a letter to Vice President Elect Richard Cheney, dated December 20, 2000.

At this stage, the Presidential Election continued to be a cliffhanger. No one had a clue whether the Democrats or Republicans would win the White House. The return of weapons inspectors to Iraq would be gift-wrapped for either of the two Presidential contenders, Vice President Al Gore or Texas Governor George W. Bush, with no party favoritism in the outcome.

By the Inauguration, the CIA expected to hand the new President the first foreign policy victory of his Administration, comparable to the release of the American hostages from the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, as President Ronald Reagan was sworn into office. The new White House could tout a major foreign policy achievement from a problem left over by the outgoing Administration. It would launch an image of muscular leadership on the world stage, for the new President. 119

All of my U.S. intelligence contacts expected gratitude from the new White House. With those expectations, we mapped out a framework for action required by Iraq.

First and foremost, Iraq would have to accept the return of weapons inspectors and maximum transparency to verify disarmament.

Secondly, Baghdad would be required to cooperate with U.S. counter terrorism goals on a number of ongoing projects.

Thirdly, Iraq would have to guarantee reconstruction contracts for U.S Corporations, post sanctions. All U.S. Corporations engaged in non-military production before the first Gulf War would have to be authorized to re-enter Baghdad, and perform at the same level of market share as they enjoyed prior to 1990. Iraq’s commitment to U.S. Corporations would have to be publicly declared and ratified to authenticate the understanding.

Does all that seem impossible?

In fact, my efforts proved far more successful than currently understood. The CIA had floated these conditions to Baghdad before agreeing to the talks. Iraq had already issued a general affirmative response before the meetings started. 120

Notably, Iraq’s Ambassador, Dr. Hasan swore that “the conversation would be short, because Baghdad was fully committed to complying with all current U.S. demands.” It would take “only a couple of weeks to hammer out the details, and no longer, ” he assured the U.S. in the December 20 letter to Vice President elect Richard Cheney. 121 Ambassador Hasan declared that he was authorized to say Baghdad would welcome “covert or non-covert talks with any U.S. official in New York or anywhere in the world.”

Infamously, newly appointed Secretary of State Colin Powell jumped on the Iraqi promise of a quick agreement on “all current U.S. demands, ” telling Congress that any talks on weapons inspections “would be a short conversation.” In doing so, Secretary Powell was paraphrasing the Iraqi Ambassador.

There was one great surprise for all of us. Newly elected President Bush appointed Andrew Card, my second cousin on my father’s side, to serve as White House Chief of Staff. That was unexpected. Critically, it must be understood that the decision to engage in covert, back channel talks was reached two months before Card’s appointment. Planning for the talks, and my first two meetings with Dr. Hasan occurred several weeks before Card’s appointment was announced. I cannot underscore enough that back channel talks never depended on my cousin’s promotion.

It was sheer fate that all of my correspondence detailing the progress of our talks to resume weapons inspections got addressed to Andy Card. In a practical sense, he filled the role of a “picture frame” for correspondence intended for the White House, CIA and national security apparatus. That satisfied one of Iraq’s chief concerns that communications should be addressed to policymakers —not the Intelligence Community. By January, 2003, that portfolio totaled 11 letters to Andrew Card, jointly received by the CIA.

The stage was set for victory. To the surprise of all, President Bush had other plans. Shortly after his Inauguration, on February 16, 2001 he ordered the bombing of Baghdad.

Instead of a “short conversation” and “fast resolution, ” preliminary talks on resuming weapons inspections dragged on another year. When the U.S. could pose no more hypothetical obstacles, FBI records show that in February, 2002, I delivered the agreement to the U.N Security Council.

In fairness, at the start of the Bush Presidency, the Administration’s war agenda remained hidden from the American public and significant parts of the Intelligence Community. Assets like me had no comprehension of the depths of President Bush’s determination to lead the world into War with Iraq.

And so, despite the February 2001 bombing, our back channel talks continued with senior Iraqi diplomats, albeit more slowly. Dr. Hasan ended his tenure as Ambassador to the United Nations and returned home to take up the post of Deputy Foreign Minister. No matter. Iraq’s new Foreign Minister, Naji Sabri, approved of the dialogue, and received communications about all meetings in Baghdad. My talks continued with other senior diplomats— Salih Mahmoud, Saad Abdul Rahmon and Abdul Rahmon Mudhian, whom Baghdad assigned to handle these dynamic communications. Our dialogue stayed highly productive.

At no time did Andy Card demand that I shut down my project, or cease functioning as an Asset or back channel to Baghdad. There was definite subterfuge by the Pro War cabal at the White House, regarding its intentions towards Iraq. They kept me in the dark, while I continued to perform faithfully.

One sees now the dilemma faced by the Intelligence Community, as it tried to serve this President. In retrospect, the world fully grasps how diplomacy posed a significant threat to the vanity of unilateralism in the Bush Administration. One sees too late that George W. Bush was a suspicious and impotent leader, who dissembled to disguise his personal weakness. He did not understand the strategic value of solving problems to maintain U.S. control of a situation. Solving problems was never his strength. So he kept everyone else off balance, in order to maintain control.

But in the opening months of his Administration, the Intelligence Community could be forgiven for the difficulties it faced trying to figure out this new master.

Campaign rhetoric throughout the 2000 Election emphasized Bush’s non-interventionist philosophy of foreign affairs. The Bush family had close relationships with the Arab-American community and received a king’s ransom of campaign funds from them. Indeed, the Bush family had longstanding ties to Saudi oil. Throughout the campaign, Bush Jr. emphasized fiscal moderation. Nobody expected George Bush to be a “buck burning” President.

For its part, the Intelligence Community saw with great clarity that the international community was ready to throw off U.N. sanctions on Iraq, and seize all those tantalizing reconstruction contracts for itself, worth tens of billions of dollars in revenues and jobs.

Over time, the Intelligence community would come to recognize President Bush’s leadership ineptitude, and experience real frustration over the burdens posed by his weakness. In the meantime, problems had to be solved.

If the United States stood down from a leadership role in problem solving, then other nations and coalitions would assert their own leadership and policy direction. That would have shut out Washington, which the CIA considered folly under any circumstance. Allowing American influence to collapse in a vacuum of White House leadership would have been a radical failure for U.S. policy in the Middle East.

In the first term of the Bush Administration, the CIA still functioned well enough to recognize that paradigm, and act on it. And so U.S. Intelligence made sure that my interaction with Iraq was heavily supervised. The CIA exercised fierce control over the agenda in all parts, and demanded that I must not challenge whatever extra demands Washington chose to impose on Baghdad. In exchange for my unquestioning obedience to the U.S. agenda, I could work towards suspending the U.N. sanctions.

For my part, my motivation was strictly humanitarian. I was horrified by the misery of Iraqi families and children.I saw the CIA as providing me with a unique and precious opportunity to contribute to the solution. So I rolled up my sleeves and got to work.

Again and again, Iraq agreed to all U.S. demands.

And very quickly I began to hunt for helpmates among my other diplomatic contacts at the United Nations—with some noteworthy success.

During the Lockerbie negotiations, I had struck up friendly relations with senior ranking diplomats from Malaysia, which served as a non-permanent member of the U.N. Security Council, under the leadership of Ambassador Hasmy Agam. 122

When back-channel talks got underway with Iraq, I approached Mr. Rani Ismail Hadi Ali, my contact at the Malaysian Embassy, for help. There’s no point in U.S. Intelligence denying it. My relationship with Mr. Rani Ali and Malaysia’s input on Iraq are substantiated by phone taps, letters and email communications.

Malaysia’s support for the peace process, and its advice throughout this back channel process, was quite precious.

Malaysia proved an outstanding partner, in fact. Malaysia 123 boasts a vibrant Islamic community and vast wealth as one of Asia’s financial capitals, with over 30 major international banks operating in Kuala Lumpur. A major exporter of electronics and telecommunications equipment, Malaysia has a fully diversified economy, with 89% literacy in a population of 24 million. More strikingly, Islam is the official religion of the country, and the government actively promotes relations with other Islamic nations, including those in the Middle East.

In its eagerness to advance its relationship with Washington, Malaysia’s Foreign Ministry offered to assume a formal role of intermediary between Iraq and the United States in any covert talks.

It was a valuable strategic offer that promised to yield results on a full range of Middle East and Islamic issues.

Most graciously of all, Ambassador Hasmy Agam, whose career encompassed thirty years of high profile diplomacy in the Non-Aligned Movement, offered to act as the designated contact between Baghdad and the United States. His participation offered a way to jump start talks on all matters of the conflict, since it was understood that Iraq and the United States could not sit down together, despite Baghdad’s oft expressed desire to do so. The outstanding leadership of Ambassador Agam provided a way forward. He assigned Rani Ali, an expert on U.N. sanctions policy who staffed him on the Security Council, to liaison with me for guidance, as talks moved forward. 124

Without explanation, Republican leaders took no action on Malaysia’s generous offer— and so squandered a powerful alliance, which could have interceded on a number of difficult Middle Eastern matters.

Though disappointing, in fairness, U.S. intelligence had already voiced a strong determination to retain control of any settlement with Iraq. They weren’t eager for international participation. However, it was also clear that Republican leaders failed to grasp how strategic alliances could be leveraged to strengthen U.S. influence in other parts of the world. The Bush White House was so myopic that it could not understand how partnerships would be reciprocated by advancing U.S. priorities in those regions, and moving other nations’ domestic policies closer to ours.

Diplomacy was too subtle for Republican leaders, even when it was designed to dictate outcomes controlled by the United States, and favorable to our agenda. In a global age, Republican leaders did not understand that proactive management would create strategic foundations that strengthen America. They did not understand why problems should be solved proactively at all.

Now that critical weakness in Republican foreign policy began to show.

For its part, the CIA faced the unhappy prospect of bucking the Bush Administration, while it experienced what appeared to be a steep learning curve.

All of us accepted the challenge. For its part, Malaysia’s commitment on behalf of the international community was truly exemplary. Ambassador Agam was like a teacher, sharing the wealth of his lifetime expertise with the rising generation of Malaysia’s diplomatic staff. It was an exciting embassy to visit, very active and dynamic. In that spirit of cooperation, Malaysia’s Embassy provided a sounding board and vital technical guidance for my preliminary talks on the weapons inspections. Ambassador Agam and Mr. Rani Ali guaranteed that back-channel talks would conform to U.N. standards of compliance once it got through U.S. gates.

For his efforts to rebuild peaceful relations with America and Iraq’s neighbors in the Middle East, Iraq’s Ambassador Dr. Hasan should have won the Nobel Peace Prize, along with Malaysia’s Ambassador Agam.

Dr Hasan showed true vision of what would be necessary to restore Iraq’s economy and infrastructure after sanctions, while Ambassador Agam and his diplomatic staff stood offstage, quietly contributing to a successful resolution. I have never known any individuals who deserved a Nobel Peace Prize more than those two.

Ambassador Agam’s prodigious diplomatic talent was fully recognized and rewarded by Malaysia’s appointment to chair the Non-Aligned Movement in 2003.

On account of all those contributing factors, by July 2001, a successful peace with Iraq was within the world’s grasp.

It looked so hopeful. On all matters, Iraq agreed to U.S. conditions again and again, in total contradiction to what Americans were told before the War. All matters large and small were resolved through back channel dialogue. 125 Diplomacy proved a great success.

Revealingly, Iraq’s enthusiasm to resume inspections quickly was only outdone by Washington’s extraordinary reluctance to get started. It began to appear the U.S. was dragging its feet out of awareness that Iraq had nothing left to disclose or destroy,. It looked like leaders on Capitol Hill recognized the wastefulness of the exercise, and were afraid of it. Meanwhile Baghdad hankered to get started. Iraqi officials saw the momentum for change coming from the international community and pushed forward to greet the new day. They were excited to provide verification that old weapons stocks had been destroyed long ago.

The behavior of Iraqi officials, and especially their eagerness to resolve the impasse, convinced me totally and without qualm that no weapons of mass destruction or illegal production facilities would be discovered inside the country.

I am convinced the Intelligence Community could read the tea leafs, too. It did not look good for U.S. propaganda on Saddam’s illicit weapons production.

My job was not to criticize, however. It was to secure maximum compliance, and to wrest as many concessions from Baghdad as possible, as part of a comprehensive solution. I kept going.

Over the next 18 months of back channel talks, Iraq’s offer to the United States came to encompass all of the following: 126

1. As of October, 2000, Baghdad agreed to resume U.N. weapons inspections. That was 18 months before the world community was told of Baghdad’s acquiescence.

2. As of October, 2000, Iraq promised to include U.S. Oil Companies in all future oil exploration and development concessions. Taking contracts from Russia or European countries would have been controversial, and politically impossible. However, Iraq had ways of cutting U.S. Oil into the mix of existing contracts.

Iraq also promised to invest in major purchases of U.S. oil equipment, which it freely declared to be the best in the world.

3. Baghdad offered to buy 1 million American made automobiles every year for 10 years to replace its citizens’ outdated fleet of automobiles. Because of purchase restrictions under U.N. sanctions, most automobiles in Iraq predated the mid 1980's. Iraq’s imports of U.S automobiles would have translated into thousands of high-paying Labor Union jobs in the Rust Belt of the United States— concentrating heavily in Michigan, Ohio, Indiana and Pennsylvania, which otherwise have been crippled by the loss of factory investment. It would have guaranteed a foundation of prosperity for America’s workers.

4. Iraq promised to give the U.S. priority contracts in telecommunications products and services.

5. Iraq agreed to grant priority contracts to U.S. health care, hospital equipment and pharmaceuticals, in any post-sanctions period.

6. Iraq promised to give priority to U.S. factory equipment, and allow U.S. Corporations to reenter the Iraqi Market at the level that they enjoyed prior to the 1990 Gulf War. Dual use military equipment and factory production was exempt from this promise.Dr. Fuisz gave critical testimony in the Congressional investigation of U.S. corporations that supplied weapons to Iraq before the first Gulf War. There was no danger he would have tolerated or mistakenly supported dual use contracts, in addressing opportunities for American corporations in post sanctions Iraq.

7. Iraq agreed to contribute as a major partner in U.S. anti-terrorism efforts.

Time and again, Baghdad made it crystal clear: Any special preference Washington demanded, the United States could have—anything at all.

Every offering was reported to Andy Card and my CIA handler, Dr. Fuisz. We followed the same strategy and reporting process that had worked so successfully during the Lockerbie talks.

There were no surprises at CIA Headquarters. The CIA fully understood my way of thinking— that both sides urgently needed to find new ways to address our problems. And for all the insults I suffered from the Justice Department after my indictment, I was very good at what I did. Throughout the 1990's, everybody was pleased on both sides. The Arabs loved me, and the CIA praised me, too.

Because of Iraq and Libya’s pariah status, other foreign Intelligence Agencies had a legitimate interest in my activities, as well. In fact, I suspect I was a primary source for most of the foreign intelligence networks tracking Iraq and Libya right up to the War— and particularly during the weapons inspections talks and the 9/11 investigation.

By example, British Intelligence would often shadow my dinners or lunches at restaurants in Manhattan, when I dined with senior diplomats on the Security Council, like Malaysia— or diplomats from Iraq or Libya to discuss the progress of back channel talks or anti-terrorism matters.

It had a comical side for sure. Several times an upper-crust British couple would arrive at the restaurant on the heels of my diplomatic host. They would take a table close by. I would watch as a dollar bill (presumably of high denomination) would slide across the table. In a crowded restaurant in New York City, bustling with activity, the British couple would order no food— only tea or coffee and water. They would not be interrupted by waiters for the next two to three hours, while my lunch or dinner conversation proceeded nearby. As my guest and I got up to leave the table, they would call the waiter— presumably to leave another large tip.

With all that surveillance, and scrutiny of my work by Dr. Fuisz and Hoven, could the Justice Department truly have been ignorant of our relationship all those years? Could they have seriously believed I was acting as an “Iraqi Agent?”

It seems impossible to me. I believe their motivation was very different. Because of my high level access to Iraq’s Embassy at the United Nations, I had vast knowledge of opportunities for a comprehensive peace with Baghdad, including promises of economic contracts for U.S. corporations and Iraq’s cooperation with the 9/11 investigation, that the U.S. and Britain urgently wanted to hide.

Given my passionate activism against war and sanctions, it was a good bet that I would talk.

And I would have a lot to say.

Shortly after September 11, retired General Wesley Clark spoke with Tim Russert of NBC News about a call he received after the strike. A member of a foreign think tank rang General Clark on his cell phone, urging him to claim 9/11 originated from Iraq at the direction of Saddam Hussein. Now, General Clark isn’t accustomed to taking orders from strangers. But he was curious about this call to his private cell phone. He asked the caller to provide evidence supporting this accusation. The conversation ended quickly, without the evidence. And that was that.

Apparently General Clark gave the motivation for War with Iraq a great deal of thought over the years. At a major speech in Texas in 2006, he said:

“Now why am I going back over ancient history? Because it’s not ancient history, because we went to war in Iraq to cover up the command negligence that led to 9/11. And it was a war we didn’t have to fight. That’s the truth—”

“I’ve been in war. I don’t believe in it. And you don’t do it unless there is absolutely, absolutely, absolutely no alternative.” 127

General Clark’s argument that War with Iraq was a diversionary strategy to distract angry Americans from the command failure before 9/11, stands out as unique and provocative among the upper echelons of the military. I agree wholeheartedly with his assessment. Only I take his conclusions one step farther. I believe that when his theory of “command negligence” gets factored in with my team’s advance warnings to the Office of Counter-Terrorism in August 2001, there is finally a “coherent” explanation for 9/11— if allowing an attack on sovereign territory of the United States could be described as a “rational” thought process.(Obviously, it’s not.)

Consider the military lexicon for command responsibility:

Command: (Department of Defense) 1. Command includes the authority and responsibility for effectively using available resources, and for planning the deployment of, organizing, directing, coordinating, and controlling military forces for the health, welfare, morale, and discipline of assigned personnel. 128

Negligence: Failure to exercise the care that a reasonably prudent person would exercise in like circumstances.”

How can we assess whether “command negligence” actually occurred?

The first level of proof examines the Commander in Chief’s use of available military resources to try to thwart the attack on U.S. soil, and whether or not those resources got deployed in an appropriate fashion.

Consider, first of all, that the North American Aerospace Command (NORAD) had practiced military responses to attacks on major buildings,including the World Trade Center, in the two year period before September 11. 129 In one exercise, fighter craft performed a mock shoot down over the Atlantic Ocean of a jet supposedly laden with chemical poisons headed toward a target inside the United States. In another scenario, the target was the Pentagon — That drill stopped after Defense officials declared the attack scenario unrealistic.

The point is that NORAD had trained to confront an attack on U.S. soil exactly like this one. Ironically, the Pentagon organized the military exercises after U.S. intelligence exposed a master plot to hijack commercial jetliners, and use them as aerial weapons to strike the World Trade Center. Sound familiar?

Called “Project Bojinka, ” the plot was hatched by Ramzi Yousef, chief mastermind of the 1993 World Trade Center attack, as a way to fulfill his dream of toppling the twin towers. Yousef was captured in the Philippines in 1995 and extradited to the United States. Convicted at trial in 1996, he was sentenced to life without parole. His co-conspirator, Sheikh Abdul Rahman, a famous, blind Egyptian Islamic radical, agitated for the violent overthrow of President Hosni Mubarak.

Yousef has emerged as a central character in the history of Al Qaeda and 9/11. A tactical mastermind with exceptional gifts for creating chaos and misery,Yousef spoke several languages fluently, and graduated with an electrical engineering degree from Swansea University in Wales. He joined Al Qaeda in 1988 as a bomb maker. Born near the Afghani/Pakistan border, Yousef’s family lived smack in the cultural milieu that produced the radical Muslims recruited, trained and funded by Washington to fight the Russians in Afghanistan.

It was Yousef who devised the tactical model for September 11 from his hide-out in Manila, capital of the Philippines, where he fled after the 1993 World Trade Center bombing.

The ambitious “Bojinka” project aspired to hijack eleven commercial jets on the same day, which would be used as missiles to strike the White House, the CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, and other national symbols of U.S. global pre-eminence, including the World Trade Center.

Philippine police struck gold when they broke up a meeting of Muslim terrorists in Manila during 1995. They suspected this visiting bomb maker had been involved in several local terrorist attacks, as well.

They arrested Yousef, confiscated his computer, then enlisted the help of a local computer expert to decode the hard drive. That’s how Filipino authorities discovered “Bojinka—” to their credit.

Yousef’s diabolical plot was no secret. The scheme was unveiled at his trial in New York in 1996, at the federal courthouse a few blocks from the World Trade Center.

Vince Cannistraro, former Director of the CIA’s Counter Terrorism Division called it “extraordinarily ambitious, very complicated to bring off, and probably unparalleled by other terrorist operations that we know of.” 130

For the next few years, “Bojinka” lay dormant.

Then, in the spring of 2001, U.S. Intelligence got wind that terrorists intended to carry out a strike remarkably similar to “Bojinka.” Concern reached such a heightened status that starting in April, 2001 and throughout the summer, I was ordered to tackle my Iraqi sources for any fragments of actionable intelligence, regarding its execution.

At the same time,

NORAD was planning war

games in Canada and Alaska

—thousands of miles from

the potential target, already identified as the World

Trade Center in New York

City. “Operation Northern

Vigilance”

131 was a major

military exercise

synchronized to coincide

with a Russian military

exercise near Alaska. As

part of that training, the US

Air Force was supposed to

simulate the protection of

North American air space,

as though Russia was

attacking the U.S

132

(i, ii,

iii)

At the same time,

NORAD was planning war

games in Canada and Alaska

—thousands of miles from

the potential target, already identified as the World

Trade Center in New York

City. “Operation Northern

Vigilance”

131 was a major

military exercise

synchronized to coincide

with a Russian military

exercise near Alaska. As

part of that training, the US

Air Force was supposed to

simulate the protection of

North American air space,

as though Russia was

attacking the U.S

132

(i, ii,

iii)

The U.S. Air Command scheduled the War Games in Canada and Alaska to run from September 10 – 14th.

Critically, the U.S. Air Force ordered personnel to operate on a state of heightened security throughout the Continental United States to defend against any intrusion on U.S. airspace on those days.

NORAD had trained for “Bojinka” for two years.

And yet, inexplicably, the full scope of rationale for the heightened security alert was never explained to the military.

Indeed, NORAD has acknowledged that U.S.forces were advised to go on alert only because of the Russian military exercises. The U.S. military was not warned “Bojinka” might be in play, though factions of U.S. intelligence were shouting from the rooftops about a possible attack, and pleading for multi-agency cooperation at that very moment.

Failure to adequately alert and deploy the Central Command of the U.S. Armed Forces, despite the heightened security risk against a known target definitely qualifies as “command negligence.”

Through no fault of its own, because of poor communications from the White House, the U.S. military was only half loaded for a massive strike against the United States, when it should have been fully braced to confront a major domestic assault.

Subsequently, Air Force commanders experienced confusion on September 11. The regional NORAD commander for New York and Washington reported that some commanders at NORAD thought 9/11 was part of the military exercises.

“In retrospect, the exercise should have proved to be a serendipitous enabler of a rapid military response to the terrorist attacks on September 11, ” 133 said Colonel Robert Marr, in charge of NEADS. “We had the fighters with a little more gas on board. A few more weapons on board.”

However, other NORAD officials were initially confused about whether the 9/11 attacks were real— or part of the exercise.” 134

As a result, at the exact moment that US and foreign intelligence around the world buzzed about a massive terrorist attack on New York City, citing the World Trade Center as the primary target, the US Air Force was locked and loaded— for war games off the coast of Russia. The U.S. Air Force was on high alert throughout the Continental United States from September 10 onward — yet received no effective communication regarding a high level threat inside New York City.

With better communications, there’s no question that the Air Force would have done much better than to dispatch a single fighter jet to Manhattan and another to Washington. They would have launched all available aircraft to bring down the hijackers pronto. 135

Options for preemptive military action were definitely available.

When a small aircraft buzzed the White House in the 1980’s, missiles got placed on the rooftop to shoot down future aircraft that came too close.

A couple of months before 9/11, world leaders gathered for a G-8 World Economic Summit in Genoa, Italy. Intelligence suggested terrorists might crash an airplane into the conference building hosting the world leaders. Overnight, Genoa became heavily fortified with anti aircraft missiles, along with significant NATO Air Force protection. The G-8 Global Summit progressed unscathed.

Didn’t all of this advance intelligence warrant the deployment of a single anti-aircraft or missile battery on top of the World Trade Towers, too?

It would have been shockingly simple and cost effective to implement. Instead, the most powerful Military Command on the planet was badly misused— cut out of the loop, denied knowledge of a significant threat against the sovereign United States.

That’s hard evidence of command failure about the military level.

The second level of “command negligence” relates to the failure to coordinate an appropriate, unified response to a known threat between U.S. intelligence and federal law enforcement. Heightened cooperation between the CIA and FBI required “command leadership” from the White House. Yet despite urgent requests in August, 2001, that inter-agency cooperation never materialized.

Bottom line: “9/11 was an organizational failure, not an intelligence failure, ” 136 as John Arquilla, of the Naval Postgraduate School put it succinctly:

Consider the time line of the warnings.

According to a Joint House-Senate Congressional inquiry, 137 in March 2001 an intelligence source claimed a group of Bin Ladin operatives was coordinating an unspecified attack on U.S. soil. One of the alleged operatives resided inside the United States.

In April 2001, U.S. Intelligence learned that terrorist operatives in California and New York were planning strikes in both of those states.

Between May and July of 2001, the National Security Agency reported at least 33 chatter communications, indicating a possible, imminent terrorist attack. These

individuals appeared to possess no actionable intelligence that would have identified who, how many, when or where the attack would start. 138

In May 2001, the Intelligence Community learned that Bin Ladin supporters planned to infiltrate the United States via Canada, in order to carry out a terrorist operation using high explosives. Further investigation by the Defense Department indicated that seven individuals associated with Bin Ladin had departed various locations for Canada, Britain and the United States. 139

By May, U.S. intelligence had gathered sufficient evidence to show that some Middle Eastern terrorist group was planning an imminent attack on key U.S. landmarks, including the World Trade Center. This coincides precisely with the timing of the portentous warning from Dr. Fuisz that I must confront Iraqi diplomats, and aggressively demand any fragment of intelligence regarding airplane hijackings.

In June 2001, the Director of Central Intelligence (D.C.I) acquired information that key operatives in Bin Ladin’s organization were going underground, while others were preparing for martyrdom. 140

In July 2001, the D.C.I gained access to an individual recently traveling in Afghanistan, who reported: “Everyone is talking about an impending attack.” The Intelligence Community was also aware that Bin Ladin had stepped up his propaganda efforts to promote Al Qaeda’s cause.

On August 6, Richard Clarke presented a Daily Briefing Memo to President Bush, outlining the gravity of Al Qaeda’s threat. Sometime on August 7 or 8, I telephoned Attorney General John Ashcroft’s private staff and the Office of Counter-Terrorism at the Justice Department, with a request for an “emergency broadcast alert throughout all agencies,” seeking “any fragment of intelligence regarding possible airplane hijackings and/or airplane bombings.” I described the threat as “imminent, ” with the “potential for mass casualties.” And I cited the World Trade Center as the expected target.

On August 16, 2001, U.S. Immigration detained Zacarias Moussaoui in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

On September 4, 2001, the FBI Office in Minneapolis sent urgent cables about the Moussaoui investigation to the Intelligence Community, the Federal Aviation Administration, the Secret Service, and several other federal agencies in Washington. Despite urgent warnings from the FBI in Minneapolis about Moussaoui’s likely involvement in some terrorist conspiracy, U.S. Attorney General John Ashcroft refused to get a search warrant from the secret intelligence court in Washington 141 so they could crack open Moussaoui’s computer.

Finally, on September 10, 2001, the National Security Agency (NSA) intercepted two communications between individuals overseas, suggesting imminent terrorist activity. These communications were not translated into English and disseminated until September 12, 2001. These intercepts gave no indication what activities might occur. It remains unclear whether they referred to the September 11 attacks. 142

By any measure, U.S. intelligence performed in an outstanding capacity, anticipating the threat posed by al Qaeda.

All of which raises serious questions as to how Central Command at the White House could have allowed such valuable raw intelligence to go unused between agencies?

Various factions of U.S. intelligence buzzed that a major terrorist attack was about to occur. There was an outpouring of pleas for aggressive coordination and preemptive planning. In its frustration, the Intelligence Community made a herculean effort to break through the gridlock and appeal directly to the Justice Department.

Unhappily, law enforcement at the Justice Department received no “command” support from the Attorney General’s Office. That sort of top level mandate would have been required for cooperation to occur between Intelligence and law enforcement, which perform two very different missions. With the crucial exception of the FBI office in Minneapolis, the response at the Justice Department was abysmal.

Intelligence sharing functioned properly. Outreach to law enforcement was made in a time effective manner. Yet nothing happened.

The command leadership dropped the ball, pure and simple. Command leaders failed to pull resources across agencies to implement the most basic precautionary safeguards. There’s no question but that qualifies as a major “command failure” and “command negligence, ” as defined by General Clark and the U.S. military establishment.

The third argument for “command negligence” involves the White House failure to accept full command responsibility after 9/11.

When there’s a tragedy or crisis, Americans expect our leaders to stand forward and embrace their responsibility for the welfare of the nation, invoking the full power of their authority. As Harry Truman put it so bluntly, “The buck stops here.”

President Bush’s performance as Commander in Chief at the start of the attack was awkward at best. At a town hall meeting in Orlando, Florida on September 12, a young audience member addressed President Bush.

Question: “One thing, Mr. President, you have no idea how much you’ve done for this country. And another thing is that – how did you feel when you heard about the terrorist attack?”

PRESIDENT BUSH: “Well – Well, Jordan, you’re not going to believe where – what state I was in, when I heard about the terrorist attack. I was in Florida. And my chief of staff, Andy Card – well, actually I was in a classroom, talking about a reading program that works. And it – I was sitting outside the – the classroom, waiting to go in, and I saw an airplane hit the tower of a – of a – you know. The TV was obviously on, and I – I used to fly myself, and I said, “Well, there’s one terrible pilot.” And I said it must have been a horrible accident.” 143

The President’s statement was largely incoherent. Somehow he translated the child’s question: “How did you feel when you heard about the terrorist attack?” to a more concrete “What state was I in when I heard about the terrorist attack?” “Oh Florida.” He interjected seemingly random comments about my cousin, Andy Card, and barely made it through the answer. This sort of disconnected rhetoric was typical and expected by those who followed President Bush closely.

[Crucially, in this statement, President Bush admitted knowing about the Mossad video of the first airplane crashing into the towers. That video becomes very important for identifying Israel’s advance knowledge about 9/11, on the morning of September 11. See Chapter 7]

More than that discredited the White House. After 9/11, Republican leaders pushed very hard, as long as possible, to avoid an investigation, hiding from criticism of their pre-9/11 inertia. When the 9/11 Commission was finally established, the White House designated a budget nowhere close to sufficient for a serious investigation.

Blue ribbon commissions are a trademark of the federal government. When a topic appears too hot for Congress to handle, a commission of distinguished officials gets appointed from the top ranks of both political parties to address it. But President Bush and Vice President Cheney wanted no part of a 9/11 investigation. Indeed, Cheney rang up Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle (Democrat-South Dakota) and asked him to limit the investigation to communication failures between agencies. 144

“The Vice President expressed concern that a review of what happened on September 11 would take resources and personnel away from the war on terrorism, ” Senator Daschle told CNN.

Unable to stop the 9/11 investigation, the White House tried to starve the Commission of funds, finally allocating an $11 million budget, a pittance of what Congress spends on far less important tasks.

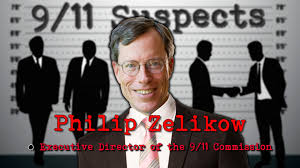

Once the 9/11 Commission was formed,

the White House saw to it

that a White House insider

was selected for the all

important job of Staff

Director. Phillip Zelikow

was a close professional

colleague of Condeleeza

Rice. They wrote a book

together on foreign policy,

and Rice brought Zelikow

onto the Bush 2000

transition team. An

academic of some

distinction, Zelikow

authored two notable

position papers for the Bush

transition team. The first studied how to manage

terrorist threats. The second

justified a preemptive

invasion of Iraq.

Once the 9/11 Commission was formed,

the White House saw to it

that a White House insider

was selected for the all

important job of Staff

Director. Phillip Zelikow

was a close professional

colleague of Condeleeza

Rice. They wrote a book

together on foreign policy,

and Rice brought Zelikow

onto the Bush 2000

transition team. An

academic of some

distinction, Zelikow

authored two notable

position papers for the Bush

transition team. The first studied how to manage

terrorist threats. The second

justified a preemptive

invasion of Iraq.

In other words, Zelikow was neck deep in the policies that produced the command negligence for 9/11 and the preemptive invasion of Iraq.

It’s hardly surprising that so much information in this book never got published in the 9/11 Commission report. General Clark stops short of declaring that President Bush engaged in “deliberate” command negligence, in order to justify going to War with Iraq. He leaves open the possibility that top White House officials showed gross incompetence in their organizational leadership, and may have used the Iraq War as a distraction from their own mediocrity.

That’s where I diverge from General Clark’s outstanding arguments. I take a stronger position. I agree that “command negligence” occurred, building up to 9/11. But I know for a fact that key leaders deliberately ignored multiple advance warnings presented by domestic and foreign intelligence sources, and willfully failed to enact the most basic cautionary measures to defend the World Trade Center—which was already identified as the primary target of the attack.

That raises the most controversial questions that have spun through the 9/11 Truth Community for years: Was 9/11 allowed to happen, or made to happen —in order to manipulate public rage into support for President Bush’s secret agenda of invading Iraq?

Put more succinctly: Did the White House practice “deliberate negligence” to create a Pearl Harbor Day that would push the U.S. into War with Iraq?

Unequivocally, I believe the answer is yes.

For its part, a faction of U.S. Intelligence had analyzed potential flash points for future tensions with Iraq, and moved to neutralize them. The peace framework addressed all major U.S. objectives in Iraq, including some not previously considered by the Bush Administration.

The White House was thoroughly apprised of all progress to implement those goals in Baghdad—and by corollary, our rapidly sinking sanctions policy That illustrates damnably why the Pro-War camp needed 9/11. Neoconservatives needed to set up Saddam’s government as a paper-tiger, an external enemy that would incite popular hatred, and overcome international resistance to War.

Neo-conservatives had lost all legitimate justifications for War. So they had to invent one.➽➽➽ Osama bin Laden saved the day, when he came along with a conspiracy to hijack airplanes and strike the Twin Towers. Right up to that point, the Bush Administration had lost every other excuse for War. It was flatly impossible.

Was the goal seizing Iraq’s oil after all? Vice President Cheney fought for years to protect the confidentiality of his pre-invasion meeting with U.S. oil executives. But there have been enough leaks to speculate that Cheney carved up Iraq’s oil reserves, and replaced the existing contracts held by foreign oil companies.

In testimony before Congress, U.S. oil executives denied that such a meeting with Vice President Cheney occurred. But in late 2005, a White House document confirmed that Cheney’s meeting took place. 145

There’s also the matter of the Caspian Sea Pipeline, which runs from Kazakhstan through Iran. A primary source of Russian oil, the Caspian Pipeline is geographically sensitive to hostilities between Iran and the West. It’s entirely possible that top officials wanted to concentrate U.S. military bases in Iraq, on the border of Iran, as a check on Tehran’s ambitions to dominate and manipulate oil supplies. Looking at the map of military bases surrounding Iran, it’s obvious they’ve done it.

Unhappily for Capitol Hill cronies of the oil industry, instead of securing vast wealth for its stockholders, war and sanctions accomplished their own worst ambitions.Sanctions fundamentally annihilated Iraq’s oil infrastructure and pipelines for the foreseeable future. Cost prohibitive damage was exacerbated by repeated acts of sabotage by Iraq’s nationalist insurgency. A large percentage of Iraqi people are convinced the United States invaded Iraq to seize its oil resources. A critical sub-group of that population chose to degrade their own oil infrastructure, rather than allow the U.S. to steal Iraq’s national wealth.

For me, that’s heart breaking to watch. I know from personal experience the ripples of advance warnings that ran like wildfire through the intelligence community before 9/11. I recall my own desperate efforts to reach the Justice Department, at the urgent command of my CIA handler. And I know the White House floated the idea of War in Baghdad for months before the attack, because I was commanded to issue those threats myself, if a 9/11 scenario occurred and Baghdad failed to share intelligence with the U.S.

On the morning of my arrest, one more thing threatened pro-War Republicans. I had full knowledge of Iraq’s efforts to cooperate with the 9/11 investigation, and how that effort had been snubbed.

I was always one to call a spade, a spade. Citing my direct contact with Iraq, I was ready to turn Washington on its ear, declaring the War on Terrorism a “fraud” and the White House rejection of peace an act of public deception.

Those in the intelligence community, who had watched me work for a decade, had no doubt that I would do it.

Finally you are told some facts. Surely they make a great deal more sense than the semantic games played in Washington all these years. Yes, the greatest Intelligence Community in the world expected a major terrorist strike according to a 9/11 style scenario. We lacked actionable intelligence to identify airport hubs or flight numbers, which would have been necessary to stop the attack. Yet far more tragically, the command leadership necessary to coordinate that preemptive inter-agency effort — or deploy anti-aircraft guns on top of the Trade Center, or activate NORAD during its pre-scheduled military exercises— failed to mobilize.

It was not for lack of trying by those of us at the mid-level, below the leadership. We raised the alarms. Alas, Republicans at the command level chose not to act.

Instead, throughout the summer of 2001, the U.S threatened Iraq with military retaliation “worse than anything they suffered before, ” if a 9/11 style attack occurred. Yes, U.S. Intelligence abhorred the concept of a 9/11 attack,including my own handlers. But a handful of puppeteers controlling the stage at the highest levels of government aggressively prepped some factions of U.S. Intelligence to accept War with Iraq as the inevitable outcome of the 9/11 strike. In which case, they made no effort to block 9/11, so they could fulfill their quest.

Adding to the confusion, most Americans have wrongly split between two stark choices: Either they think airplanes brought down the World Trade Center – or a controlled demolition using military grade weapons accomplished the evil deed. Until now, arguments on both sides have been framed to cancel the other out.

From where I sit it’s obvious that both the airplane hijackings and the controlled demolition were synchronized to play off each other.

9/11 was like a magician’s trick. All eyes were watching the airplanes on the left, while the real sleight of hand was happening on the right. In other words, the airplane hijackings provided a “cover” for the controlled demolition of the Twin Towers.

In spy circles, it’s known as a “cover and deception” operation.

It’s critical to understand that Intelligence is not a monolithic mega entity, but a community of factions, broken down into small teams. Once advance warnings about the World Trade Center attack get factored into the equation, it’s entirely conceivable that some different team, in a competing faction—called an “orphan, ” entered the World Trade Center in the midnight hours, and positioned explosives throughout the buildings, with the intention of maximizing the detonation impact on whatever day the hijacked airplanes struck the buildings.

All crimes require motive and opportunity. By my count, the “orphan team” had six months of warning time to acquire explosives and map out a detonation pattern. And that threat of War with Iraq provided the missing “motive” to do the unthinkable.

Regrettably, everything falls into place in the Terror Timeline once Washington’s advance threats against Iraq are factored in.

Does that truth satisfy you?

It has cost me a great deal to tell you. I have waited a long time and suffered through a frightening and horrific ordeal for my chance, spending a year in prison on a Texas military base without a trial or guilty plea, as you’re about to discover.

That ugliness was coming faster than I ever dreamed. However, have some patience, friends. First, some more truth. Because you see, just as I warned about the 9/11 attack, I was also a “first responder, ” covering Iraq’s cooperation with the 9/11 investigation.

I told you. I know everything. Those facts have been concealed from you, as well. And they are more devastating than you know.

First though, think back with me. Do you remember what you were doing when you first heard that an airplane had crashed into the World Trade Center? Did you hear it on the radio, driving to work? Were you taking the children to school? Can you recall your split second reaction to the news?

I was at the Post Office in Takoma Park, my tiny peacenik hamlet in the suburbs of Washington DC. Someone behind me groaned excitedly that a crazed, grief stricken pilot must have committed suicide.

I recall my split second reaction like a punch in the gut: We knew it! Richard and I told them this was coming. Oh God, why didn’t they listen to us?

I rushed home and got on the phone with Dr. Fuisz. Shouting over each other at the carnage playing on our televisions, we commanded office workers not to go back inside the damaged towers. I demanded that Richard stop them. In my grief, I endowed him with super human strength to right all wrongs, fly down amidst the chaos, and issue vital instructions for the preservation of the crowds.

To no avail. On September 11, 2001, 3,017 souls lost their lives, and 6,291 were seriously injured when the Twin Towers of black glass imploded and crashed to the concrete floor in a frightening cloud of thermatic dust.

Fire-fighters and rescue workers died with them.

Alas, 9/11 proved that none of us are super human. Not to diminish the irresponsibility of the government’s role, but I seriously doubt the inner circle of U.S officials comprehended the full power of the blow, or the scope of repercussions, when they made the fatal decision not to block that hideous attack. In all likelihood, they expected only minor damage, according to the scope of what had come before.

To put that in context, the 1993 World Trade Center attack killed just 5 people—and wounded 1,000. The bombing of the U.S.S. Cole in Yemen killed 17 people.

I mean, come on. Nobody imagined the Titanic would sink either. Right?

The Titanic did sink, though, didn’t it? And more government officials had been debriefed about this “imminent” terrorist threat in late August or September than Americans would like to imagine. Everybody we could think of had been warned.

Most intelligence teams would have concluded that airplanes alone could not bring down the Towers. If the goal was maximum destruction, it would require some help. And don’t forget there was six months of advance time to plan a “cover and deception” operation that would exploit the airplane hijackings, as a false flag to complete the job.

That’s how it happened.

Many times I’ve been questioned about Dr. Fuisz’s other sources, who fed him intelligence before the attack. Truthfully, he never revealed them to me.

But I have guessed. Shortly after the first tower collapsed—but before the second tower collapsed, Dr. Fuisz blurted something to me over the phone. It regarded the videotape of the first hijacked airplane flying over the Manhattan harbor moments before ramming full force into the World Trade Center. The video camera was held by steady hands in a controlled setting, not whipped around by an amateur bystander, responding hysterically to surprising, fast breaking events.

Dr. Fuisz demanded to know if I thought it was “an accident that a man and woman happened to be waiting on the sidewalk with a video camera, ready to record the attack?”

He was highly agitated.

“How often does a bystander have a camera cued up to record a car accident on the street? It never happens, Susan. It never happens.” He challenged me.

Then Dr. Fuisz said, “Those are Israeli agents. It’s not an accident that they were standing there. They knew this attack was coming. They were waiting for it all morning.”

In my grief, I was outraged and shocked by the images on television. I shot back something to the effect of—

“You mean to tell me, we’ve been looking for intelligence on this attack for months! And Israel knew the whole time? And they didn’t tell us?” I was madder than hell.

Immediately the phone line cut dead between us. I called him right back.

Very calmly, he said, “Susan, we must never talk about that again.”

We never did. But it prompts serious questions. Did the Israelis fail to warn us? Or did Israel provide a broad outline of the attack, but withhold crucial details that would have empowered the CIA to defeat it?

Or did White House officials ignore Israel’s warnings like they ignored everybody else? Dr. Fuisz gave no hint.

A couple of details are worth noting, however. Dr. Fuisz was knowledgeable about the team’s intelligence identities and the existence of the videotape about 24 hours before the corporate media started broadcasting footage of airplanes striking the Towers, on September 12.

Now, Dr. Fuisz enjoyed absolute superiority in his intelligence sources. But this video must have been distributed to the top echelons of U.S. Intelligence with lightning speed to become available so quickly—before the second Tower collapsed. That would signify the video was filmed by a friendly Intelligence Agency like the Mossad. Only somebody with top access inside the CIA could pull that off so rapidly.

That also explains the extraordinary remarks by President Bush— how he saw footage of the first airplane crashing into the Towers before he entered the classroom in Florida. Bush guffawed that he thought the pilot was lousy. The second plane crashed into the World Trade Center while President Bush was reading to the children. My own cousin, Andy Card, whispered in his ear, when the second crash happened.

Is that significant? I could be wrong. But I would say it’s huge.

Obviously President Bush saw video of the first airplane crashing into the Towers. And so did Dr. Fuisz. It was filmed by the Mossad— which enraged us both. I am convinced the White House spiked the video’s release, realizing that our reaction would be universal. At warp speed, Americans would know that our ally, Israel had advance knowledge about 9/11—Or worse.

So why the hell didn’t they speak up?

One more thing occurred that morning. Dr. Fuisz and I made a crucial decision in the first hours after the attack. Whether it proved correct or not, I leave history to judge.

We agreed to avoid recriminations in the first days after the attack. U.S. Intelligence did not need to hear ‘we told you so’s.’ Not from us. It was not a conspiracy of silence. We never agreed to bury the truth. We only agreed to delay confronting it. Everybody recognized a terrible mistake had been made. Everybody knew our team had warned about the threat. We’d been highly vocal. What they needed most urgently was Our Help — and the help of everyone with special access to high level sources close to Middle Eastern terrorism. They needed us. Beating up the Intelligence Community in those first days would have demoralized the very men and women who now had to mobilize all of their energies to launch an effective investigation.

We wanted to contribute. And so we decided to wait before calling attention to our team’s accurate predictions. I always expected a Congressional inquiry to bring our advance warnings to light. It was a question of a few weeks, I figured, while everyone focused on the criminal investigation.

There would be enormous repercussions from our decision. I myself would suffer appalling personal consequences. We had no way of knowing how serious or terrible.

As they say, the road to hell is paved with best intentions.

For me, it meant the abyss.

next

IRAQ’S COOPERATION

WITH 9/11 INVESTIGATION

The CIA would move heaven and earth to protect market access for U.S. corporations in any post sanctions period.

And so, in November, 2000, while votes in Florida were still getting counted, I sat down with Dr. Hasan at the Ambassador’s House in New York to hold preliminary talks on resuming the weapons inspections.

The meetings in November and December, 2000 culminated in a letter to Vice President Elect Richard Cheney, dated December 20, 2000.

At this stage, the Presidential Election continued to be a cliffhanger. No one had a clue whether the Democrats or Republicans would win the White House. The return of weapons inspectors to Iraq would be gift-wrapped for either of the two Presidential contenders, Vice President Al Gore or Texas Governor George W. Bush, with no party favoritism in the outcome.

By the Inauguration, the CIA expected to hand the new President the first foreign policy victory of his Administration, comparable to the release of the American hostages from the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, as President Ronald Reagan was sworn into office. The new White House could tout a major foreign policy achievement from a problem left over by the outgoing Administration. It would launch an image of muscular leadership on the world stage, for the new President. 119

All of my U.S. intelligence contacts expected gratitude from the new White House. With those expectations, we mapped out a framework for action required by Iraq.

First and foremost, Iraq would have to accept the return of weapons inspectors and maximum transparency to verify disarmament.

Secondly, Baghdad would be required to cooperate with U.S. counter terrorism goals on a number of ongoing projects.

Thirdly, Iraq would have to guarantee reconstruction contracts for U.S Corporations, post sanctions. All U.S. Corporations engaged in non-military production before the first Gulf War would have to be authorized to re-enter Baghdad, and perform at the same level of market share as they enjoyed prior to 1990. Iraq’s commitment to U.S. Corporations would have to be publicly declared and ratified to authenticate the understanding.

Does all that seem impossible?

In fact, my efforts proved far more successful than currently understood. The CIA had floated these conditions to Baghdad before agreeing to the talks. Iraq had already issued a general affirmative response before the meetings started. 120

Notably, Iraq’s Ambassador, Dr. Hasan swore that “the conversation would be short, because Baghdad was fully committed to complying with all current U.S. demands.” It would take “only a couple of weeks to hammer out the details, and no longer, ” he assured the U.S. in the December 20 letter to Vice President elect Richard Cheney. 121 Ambassador Hasan declared that he was authorized to say Baghdad would welcome “covert or non-covert talks with any U.S. official in New York or anywhere in the world.”

Infamously, newly appointed Secretary of State Colin Powell jumped on the Iraqi promise of a quick agreement on “all current U.S. demands, ” telling Congress that any talks on weapons inspections “would be a short conversation.” In doing so, Secretary Powell was paraphrasing the Iraqi Ambassador.

There was one great surprise for all of us. Newly elected President Bush appointed Andrew Card, my second cousin on my father’s side, to serve as White House Chief of Staff. That was unexpected. Critically, it must be understood that the decision to engage in covert, back channel talks was reached two months before Card’s appointment. Planning for the talks, and my first two meetings with Dr. Hasan occurred several weeks before Card’s appointment was announced. I cannot underscore enough that back channel talks never depended on my cousin’s promotion.

It was sheer fate that all of my correspondence detailing the progress of our talks to resume weapons inspections got addressed to Andy Card. In a practical sense, he filled the role of a “picture frame” for correspondence intended for the White House, CIA and national security apparatus. That satisfied one of Iraq’s chief concerns that communications should be addressed to policymakers —not the Intelligence Community. By January, 2003, that portfolio totaled 11 letters to Andrew Card, jointly received by the CIA.

The stage was set for victory. To the surprise of all, President Bush had other plans. Shortly after his Inauguration, on February 16, 2001 he ordered the bombing of Baghdad.