The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia

By Alfred W. McCoy with

Cathleen B. Read

and Leonard P.Adams II

In late November General Phourni's army began its drive for Vientiane, Laos's administrative capital. Advancing steadily up the Mekong River valley, rightist forces reached the outskirts of the city on December 14 and evicted Capt. Kong Le's paratroopers after three days of destructive street fighting. While Kong Le's Paratroopers beat a disciplined retreat up Route 13 toward the royal capital of Luang Prabang, General Phoumi was a bit lax in pursuit, convinced that Kong Le would eventually be crushed by the rightist garrisons guarding the royal capital.

About a hundred miles north of Vientiane there is a fork in the road: Route 13 continues

its zigzag course northward to Luang Prabang, while Route 7 branches off in an easterly

direction toward the Plain of Jars. Rather than advancing on Luang Prabang as expected,

Kong Le entered the CIA-controlled Plain of Jars on December 31, 1960. While his

troops captured Muong Soui and attacked the airfield at Phong Savan, Pathet Lao

guerrillas launched coordinated diversionary attacks along the plain's northeastern rim.

Rightist defenses crumbled, and Phourni's troops threw away their guns and ran. (99) As

mortar fire came crashing in at the end of the runway, the last Air America C-47 took off

from the Plain of Jars with Edgar Buell and a contingent of U.S. military advisers. (100)

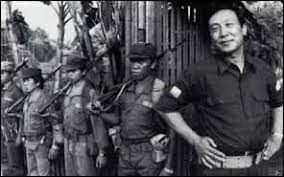

Lt. Col. Vang Pao was one of the few commanders who did not panic at the Kong Le and

Pathet Lao coordinated offensive. While Phourni's regular army troops ran for the

Mekong, Vang Pao led several thousand Meo soldiers and refugees out of the plain on an

orderly march to Padoung, a four-thousand-foot mountain, twelve miles due south. Vang

Pao was appointed commander of Military Region II and established his headquarters at

Padoung. (101)

With General Phourni once more in control of Vientiane and a joint Pathet Laoneutralist

force occupying the strategic Plain of Jars, the center of CIA activity shifted from

Savannakhet to Padoung. In January 1961 the CIA began sending Green Berets, CIA financed

Thai police commandos, and a handful of its own agents into MR 11 to build up

an effective Meo guerrilla army under Vang Pao. William Young was one of the CIA

operatives sent to Padoung in January, and because of his linguistic skills, he played a

key role in the formation of the Secret Army. As he recollected ten years later, the basic CIA strategy was to keep the Pathet Lao bottled up on the plain by recruiting all of the

eligible young Meo in the surrounding mountains as commandos.

To build up his army, Vang Pao's officers and the CIA operatives, including William

Young, flew to scattered Meo villages in helicopters and light Heliocourier aircraft.

Offering guns, rice, and money in exchange for recruits, they leapfrogged from village to

village around the western and northern perimeter of the Plain of Jars. Under their

supervision, dozens of crude landing strips for Air America were hacked out of the

mountain forests, thus linking these scattered villages with CIA headquarters at Padoung.

Within a few months Vang Pao's influence extended from Padoung north to Phou Fa and

east as far as Bouam Long. (102) However, one local Meo leader in the Long Pot region

west of the Plain of Jars says that the Meo recruiting officers who visited his village used

threats as well as inducements to win a declaration of loyalty. "Vang Pao sent us guns,"

he recalled. "If we did not accept his guns he would call us Pathet Lao. We had no

choice. Vang Pao's officers came to the village and warned that if we did not join him he

would regard us as Pathet Lao and his soldiers would attack our village." (103)

Meo guerrilla operations on the plain itself had begun almost immediately; Meo sappers

blew up bridges and supply dumps while snipers shot at neutralist and Pathet Lao

soldiers. After four months of this kind of harassment, Capt. Kong Le decided to retaliate.

(104) In early May 1961, Pathet Lao and neutralist troops assaulted the northern flank of

Padoung mountain and began shelling the CIA base camp. After enduring an intense

enemy mortar barrage for over two weeks, the CIA decided to abandon the base, and

Vang Pao led his troops to a new headquarters at Pha Kbao, eight miles to the southwest.

(105) Following close behind came Edgar Buell, leading some nine thousand Meo

civilians. While Vang Pao's hardy troops made the transfer without incident, hundreds of

civilians, mainly children and elderly, died in a forced march through the jungle. (106)

The only official report we have on Meo operations was written by Gen. Edward G.

Lansdale of the CIA in July 1961 for foreign policy officials in the Kennedy

administration. In it he discusses the Agency's clandestine warfare potential in Indochina.

"Command control of Meo operations is exercised by the Chief CIA Vientiane with the

advice of Chief MAAG Laos [U.S. army advisers]," reported Lansdale. Although there

were only nine CIA operations officers and nine Green Berets in the field, "CIA control

in the Meo operations has been reported as excellent." In addition, there were ninety-nine

Thai police commandos working with the Meo under CIA control. So far nine thousand

Meo had been "equipped for guerrilla operations," but Lansdale felt that at least four

thousand more of these "splendid fighting men" could be recruited. However, there was

one major problem:

"As Meo villages are over-run by Communist forces and as men leave food raising duties

to serve as guerrillas, a problem is growing over the care and feeding of non-combat

Meos. CIA has given some rice and clothing to relieve this problem. Consideration needs

to be given to organized relief, a mission of an I.C.A ["humanitarian" foreign aid] nature,

to the handling of Meo refugees and their rehabilitation." (107)

To solve this critical problem, the CIA turned to Edgar Buell, who set out on a fifty eight-day

trek around the perimeter of the plain to arrange for delivery of "refugee"

supplies. (108)

In July 1962 the United States and the Soviet Union signed the Geneva Agreements on

Laos, and thus theoretically terminated their military operations in that chaotic kingdom.

Although American Green Berets and military advisers were withdrawn by October as

specified, the CIA devised a number of clever deceptions to continue its clandestine

activities. All of the CIA operatives moved to adjacent areas of Thailand, but returned

almost every day by helicopter or plane to direct guerrilla operations. Civilian personnel

(not covered by the Geneva Agreements) were recruited for clandestine work. In

December 1962, for example, Buell trained Meo guerrillas in demolition techniques and

directed the dynamiting of six bridges and twelve mountain passes along Route 7 near

Ban Ban. (109) The U.S. Embassy declared that Air America flights to Meo villages,

which carried munitions as well as refugee supplies, were "humanitarian" aid and as such

were exempted from the Geneva Agreements. (110)

After a relatively quiet year in 1962, the CIA went on the offensive throughout northern

Laos in 1963-1964. In the northwest, William Young, assisted by I.V.S volunteer Joseph

Flipse, led Yao commandos in an attack on Pathet Lao villages east of Ban Houei Sai.

One American who took part in the offensive recalls that Pathet Lao troops had been

inactive since the Geneva Agreements were signed and feels that the CIA offensive

shattered the cease-fire in the northwest. In the northeast the CIA took the war to the

enemy by expanding Meo commando operations into Sam Neua Province, a Pathet Lao

stronghold for nearly fifteen years. (111)

Anthony Poe became the new CIA man at Long Tieng, Vang Pao's headquarters since

mid 1962, and organized the offensive into Sam Neua Province. Rather than attacking

towns and villages in the valleys where the Pathet Lao were well entrenched, the CIA

concentrated on the mountain ridges populated by Meo tribesmen. Using Air America's

fleet of helicopters and light aircraft, Anthony Poe led hundreds of Meo guerrillas in a

lightning advance that leaped from mountain to mountain into the heart of Sam Neua

Province. As soon as a village was captured and Pathet Lao cadres eliminated, the

inhabitants were put to work building a crude landing strip, usually five hundred to eight

hundred feet long, to receive the airplanes that followed in the conqueror's wake carrying

Edgar Buell's "refugee" supplies. These goods were distributed in an attempt to buy the

hearts and minds of the Meo.

Within a matter of months a fifty-mile-long strip of territory-stretching from the

northeastern rim of the Plain of Jars to Phou Pha Thi mountain, only fifteen miles from

the North Vietnamese border-had been added to Vang Pao's domain. Over twenty new

aircraft landing strips dotted the conquered corridor, linking Meo villages with CIA

headquarters at Long Tieng. Most of these Meo villages were perched on steep mountain

ridges overlooking valleys and towns controlled by the Pathet Lao. The Air America

landing strip at Hong Non, for example, was only twelve miles from the limestone caverns near Sam Neua City where the Pathet Lao later housed their national

headquarters, a munitions factory, and a cadre training school. (112)

As might be expected, the fighting on the Plain of Jars and the opening of these landing strips produced changes in northeastern Laos's opium traffic. For over sixty years the Plain of Jars had been the hub of the opium trade in northeastern Laos. When Kong Le captured the plain in December 1960, the Corsican charter airlines abandoned Phong Savan Airport for Vientiane's Wattay Airport. The old Corsican hangout at Phong Savan, the Snow Leopard Inn, was renamed "Friendship Hotel." It became headquarters for a dozen Russian technicians sent to service the aging Ilyushin transports ferrying supplies from Hanoi for the neutralists and Pathet Lao. (113)

No longer able to land on the Plain of Jars, the Corsican airlines began using Air America's mountain landing strips to pick up raw opium. (114) As Vang Pao circled around the Plain of Jars and advanced into Sam Neua Province, leaving a trail of landing strips behind him, the Corsican's were right behind in their Beechcraft's and Cessna's, paying Meo farmers and Chinese traders a top price for raw opium. Since Kong Le did not interfere with commercial activity on the plain, the Chinese caravans were still able to make their annual journey into areas controlled by Vang Pao. Now, instead of delivering their opium to trading centers on the plain, most traders brought it to Air America landing strips serviced by the Corsican charter airlines. (115) Chinese caravans continued to use the Plain of Jars as a base until mid 1964, when the Pathet Lao drove Kong Le off the plain and forced them into retirement.

When the Laotian government in the person of Ouane Rattikone jealously forced the Corsican's out of business in 1965, a serious economic crisis loomed in the Meo highlands. The war had in no way reduced Meo dependence on opium as a cash crop, and may have actually increased production. Although thousands of Meo men recruited for commando operations were forced to leave home for months at a time, the impact of this loss of manpower on opium production was minimal. Opium farming is women's work. While men clear the fields by slashing and burning the forest, the tedious work of weeding and harvesting is traditionally the responsibility of wives and daughters. Since most poppy fields last up to five or ten years, periodic absences of the men had little impact on poppy production. Furthermore, the CIA's regular rice drops removed any incentive to grow rice, and freed their considerable energies for full-time poppy cultivation. To make defense of the civilian population easier, many smaller refugee villages had been evacuated, and their populations concentrated in large refugee centers. Good agricultural land was at a premium in these areas, and most of the farmers devoted their labors to opium production simply because it required much less land than rice or other food crops. (116)

Meo villages on the southern and western edges of the plain were little affected by the transportation problem caused by the end of the Corsican flights. Following the demise of the Chinese merchant caravans in mid 1964, Vang Pao's commandos dispatched Meo military caravans from Long Tieng into these areas to buy up the opium harvest. Since there were daily flights from both Sam Thong and Long Tieng to Vientiane, it was relatively easy to get the opium to market. However, the distances and security problems involved in sending caravans into the northern perimeter of the plain and in the Sam Neua area were insuperable, and air transport became an absolute necessity. With the Corsican's gone, Air America was the only form of air transport available. (117) And according to Gen. Ouane Rattikone, then commander in chief of the Laotian army, and Gen. Thao Ma, then Laotian air force commander, Air America began flying Meo opium to markets in Long Tieng and Vientiane. (118)

Air logistics for the opium trade were further improved in 1967 when the CIA and U.S.A.I.D (United States Agency for International Development) gave Vang Pao financial assistance in forming his own private airline, Xieng Khouang Air Transport. The company's president, Mr. Lo Kham Thy, says the airline was formed in late 1967 when two C-47's were acquired from Air America and Continental Air Services. The company's schedule is limited to shuttle flights between Long Tieng and Vientiane that carry relief supplies and an occasional handful of passengers. Financial control is shared by Vang Pao, his brother, his cousin, and his father-in-law. (119) According to one former U.S.A.I.D employee, U.S.A.I.D supported the project because officials hoped it would make Long Tieng the commercial center of the northeast and thereby reinforce Vang Pao's political position. The U.S.A.I.D officials involved apparently realized that any commercial activity at Long Tieng would involve opium, but decided to support the project anyway. (120) Reliable Meo sources report that Xieng Khouang Air Transport is the airline used to carry opium and heroin between Long Tieng and Vientiane. (121)

Despite repeated dry season offensives by the Pathet Lao, the CIA's military position in the northeast remained strong, and Vang Pao's army consolidated and expanded upon gains it had made during the early years of the war. However, in January 1968 Pathet Lao and North Vietnamese forces mounted a general offensive that swept Vang Pao's mercenaries out of Sam Neua Province. The key to the Pathet Lao victory was the capture of the CIA's eagle-nest bastion, Phou Pha Thi, on March 11. The U.S. air force had built a radar guidance center on top of this 5,680-foot mountain in 1966 "to provide more accurate guidance for all-weather bombing operations" over North Vietnam. (122) Only seventeen miles from the North Vietnamese border, Pha Thi had become the eyes and ears of the U.S. bombing campaign over Hanoi and the Red River Delta. (123) (Interestingly, President Johnson announced a partial bombing halt over North Vietnam less than three weeks after the radar installation at Pha Thi was destroyed.) Vang Pao attempted to recapture the strategic base late in 1968, but after suffering heavy losses he abandoned it to the North Vietnamese and Pathet Lao in January 1969. (124)

The loss of Sam Neua in 1968 signaled the first of the massive Meo migrations that eventually made much of northeastern Laos a depopulated free fire zone and drastically reduced hill tribe opium production. Before the CIA-initiated Meo guerrilla operations in 1960, MR 11 had a hill tribe population of about 250,000, most of them Meo opium farmers evenly scattered across the rugged highlands between the Vientiane Plain and the North Vietnamese border. (125) The steady expansion of Vang Pao's influence from 1961 to 1967 caused some local concentration of population as small Meo villages clustered together for self defense. However, Meo farmers were still within walking distance of their poppy fields, and opium production continued undiminished.

When Vang Pao began to lose control of Sam Neua in early 1968, the CIA decided to deny the population to the Pathet Lao by evacuating all the Meo tribesmen under his control. By 1967 U.S. air force bombing in northeastern Laos was already heavy, and Meo tribesmen were willing to leave their villages rather than face the daily horror of life under the bombs. Recalling Mao Tse-tung's axiom on guerrilla warfare, Edgar Buell declared, "If the people are the sea, then let's hurry the tide south." (126) Air America evacuated over nine thousand people from Sam Neua in less than two weeks. They were flown to Buell's headquarters at Sam Thong, five miles north of Long Tieng, housed temporarily, and then flown to refugee villages in an adjacent area west of the Plain of Jars. (127)

During the next three years repeated Pathet Lao winter-spring offensives continued to drive Vang Pao's Meo army further and further back, forcing tens of thousands of Meo villagers to become refugees. As the Pathet Lao's 1970 offensive gained momentum, the Meo living north and west of the plain fled south, and eventually more than 100,000 were relocated in a crescent-shaped forty-mile-wide strip of territory between Long Tieng and the Vientiane Plain. When the Pathet Lao and the North Vietnamese attacked Long Tieng during the 1971 dry season, the CIA was forced to evacuate some fifty thousand mercenary dependents from Long Tieng valley into the overcrowded Ban Son resettlement area south of Long Tieng. By mid 1971 U.S.A.I.D estimated that almost 150,000 hill tribe refugees, of which 60 percent were Meo, had been resettled in the Ban Son area. (128)

After three years of constant retreat, Vang Pao's Meo followers are at the end of the line. Once a prosperous people living in small villages surrounded by miles of fertile, uninhabited mountains, now almost a third of all the Meo in Laos, over ninety thousand of them, are now packed into a forty-mile-long dead end perched above the sweltering Vientiane Plain. The Meo are used to living on mountain ridges more than three thousand feet in elevation where the temperate climate is conducive to poppy cultivation, the air is free of malarial mosquitoes, and the water is pure. In the refugee villages, most of which are only twenty-five hundred feet in elevation, many Meo have been stricken with malaria, and lacking normal immunities, have become seriously ill. The low elevation and crowded conditions make opium cultivation almost impossible, and the Meo are totally dependent on Air America's rice drops. If the North Vietnamese and Pathet Lao capture Long Tieng and advance on Vientiane, the Meo will probably be forced down onto the Vientiane Plain, where their extreme vulnerability to tropical disease might result in a major medical disaster.

The Ban Son resettlement area serves as a buffer zone, blocking any Pathet Lao and North Vietnamese enemy advance on Vientiane. If they choose to move on Vientiane they will have no choice but to fight their way through the resettlement area. Meo leaders are well aware of this, and have pleaded with U.S.A.I.D to either begin resettling the Meo on the Vientiane Plain on a gradual, controlled basis or shift the resettlement area to the east or west, out of the probable line of an enemy advance. (129)

Knowing that the Meo fight better when their families are threatened, U.S.A.I.D has refused to accept either alternative and seems intent on keeping them in the present area for a final, bloody stand against the North Vietnamese and Pathet Lao. Most of the Meo have no desire to continue fighting for Gen. Vang Pao. They bitterly resent his more flamboyant excesses person ally executing his own soldiers, massive grafting from the military payroll, and his willingness to take excessive casualties -and regard him as a corrupt warlord who has grown rich on their suffering. (130) But since U.S.A.I.D decides where the rice is dropped, the Meo have no choice but to stand and fight.

Meo losses have already been enormous. The sudden, mass migrations forced by enemy offensives have frequently exceeded Air America's logistic capacity. Instead of being flown out, many Meo have had to endure long forced marches, which produce 10 percent fatalities under the best of conditions and 30 percent or more if the fleeing refugees become lost in the mountain forests. Most of the mercenary dependents have moved at least five times and some villages originally from Sam Neua Province have moved fifteen or sixteen times since 1968. (131) Vang Pao's military casualties have been just as serious: with only thirty thousand to forty thousand men under arms, his army suffered 3,272 men killed and 5,426 wounded from 1967 to 1971. Meo casualties have been so heavy that Vang Pao was forced to turn to other tribes for recruits, and by April 1971 Lao Theung, the second largest hill tribe in northern Laos, comprised 40 percent of his troops. (132) Many of the remaining Meo recruits are boy soldiers. In 1968 Edgar Buell told a New Yorker correspondent that:

"A short time ago we rounded up three hundred fresh recruits. Thirty per cent were fourteen years old or less, and ten of them were only ten years old. Another 30 per cent were fifteen or sixteen. The remaining 40 per cent were forty-five or over. Where were the ones in between? I'll tell you-they're all dead." (133)

Despite the drop in Meo opium production after 1968, General Vang Pao was able to continue his role in Laos's narcotics trade by opening a heroin laboratory at Long Tieng. According to reliable Laotian sources, his laboratory began operations in 1970.When a foreign Chinese master chemist arrived at Long Tieng to supervise production. It has been so profitable that in mid 1971 Chinese merchants in Vientiane reported that Vang Pao's agents were buying opium in Vientiane and flying it to Long Tieng for processing.(134)

Although American officials in Laos vigorously deny that either Vang Pao or Air America are in any way involved, overwhelming evidence to the contrary challenges these pious assertions. Perhaps the best way of understanding the importance of their role is to examine the dynamics of the opium trade in a single opium-growing district.

Long Pot Village:

Rendezvous with Air America

Long Pot District, thirty miles northwest of Long Tieng, was one of the last remaining areas in northeastern Laos where the recent history of the opium traffic could be investigated. Located forty miles due west of the Plain of Jars, it was close enough to Long Tieng to be a part of Gen. Vang Pao's domain but far enough away from the heavy fighting to have survived and tell its story. Viewed from Highway 13, which forms its western boundary, Long Pot District seems a rugged, distant world. Phou Phachau mountain, casting its shadow over the entire district, juts more than sixty-two hundred feet into the clouds that perennially hover about its peak during the misty rainy season from May to October. Steep ridges radiate outward from Phou Phachau and lesser peaks, four thousand and five thousand feet high, form hollows and valleys that gouge the district's hundred square miles of territory. The landscape was once verdant with virgin hardwood forests, but generations of slash-and-burn agriculture by hill tribe residents have left many of the ridges and valleys covered with tough, chest-high savanna grass. (135)

The district's twelve villages, seven Meo and five Lao Theung, cling to ridges and mountain crests, where they command a watchful view of the surrounding countryside. The political center of the district is the village of Long Pot, a Meo community of fortyseven wooden, dirtfloored houses and some three hundred residents. It is not its size, but its longevity which makes Long Pot village important. Founded in the latter half of the nineteenth century, it is one of the oldest Meo villages in northeastern Laos. Its leaders have a tradition of political power, and the highest-ranking local official, District Officer Ger Su Yang, resides in Long Pot village. While most Meo are forced to abandon their villages every ten or twenty years in search of new opium fields, Long Pot village is surrounded by a surplus of fertile, limestone-laden slopes that have allowed its inhabitants to remain in continuous residence for three generations. Moreover, Long Pot village's high altitude is ideal for poppy cultivation; the village itself is forty-two hundred feet high and is surrounded by ridges ranging up to fifty-four hundred feet. The Yunnan variety of the opium poppy found in Southeast Asia requires a temperate climate; it can survive at three thousand feet, but thrives as the altitude climbs upward to five thousand feet.

Despite all the damage done by over ten years of constant warfare, opium production in Long Pot village had not declined. In an August 1971 interview, the district officer of Long Pot, Ger Su Yang, said that most of the households in the village had been producing about fifteen kilos of opium apiece before the fighting began, and had maintained this level of production for the last ten years. However, rice production had declined drastically.(136)During a time of war, when the Meo of Long Pot might have been expected to concentrate their dwindling labor resources on essential food production, they had chosen instead to continue cash-crop opium farming. Guaranteed an adequate food supply by Air America's regular rice drops, the villagers were free to devote all their energies to opium production. And since Vang Pao's officers have paid them a high price for their opium and assured them a reliable market, the farmers of Long Pot village have consistently tried to produce as much opium as possible.

In the past rice has always been the Meo's most important subsistence crop and opium their traditional cash crop. However, opium and rice have conflicting crop cycles and prosper in different kinds of fields. Because the average Meo village has a limited amount of manpower, it is only capable of clearing a few new fields every year, and therefore must opt for either opium or rice. When the opium price is high Meo farmers concentrate their efforts on the opium crop and use their cash profits to buy rice, but if the price drops they gradually reduce poppy cultivation and increase subsistence rice production. With rice from Air America and good opium prices from Vang Pao's officers, the farmers of Long Pot had chosen to emphasize opium production. (137)

Every spring, as the time for cutting new fields approaches, each household sends out a scouting party to scour the countryside for suitable field locations. Since Long Pot Meo want to plant opium, they look for highly alkaline soil near the ridge line or in mountain hollows where the opium poppies prosper, rather than mid-slope fields more suitable for rice. The sweeter "taste" of limestone soil can actually be recognized by a discriminating palate, and as they hike around the nearby mountains Meo scouts periodically chew on a bit of soil to make sure that the prospective site is alkaline enough. (138)

Meo farmers begin clearing their new fields in March or April. Using iron-bitted axes, the men begin chopping away at timber stands covering the chosen site. Rather than cutting through the thick roots or immense trunks of the larger trees, the Meo scale the first twenty feet of the trunk, balance themselves on a slender notched pole, and cut away only the top of the tree. A skilled woodsman can often fell three or four smaller trees with a single blow if be topples a large tree so that it knocks down the others as it crashes to the ground. The trees are left on the ground to dry until April or early May, when the Meo are ready for one of the most awesome spectacles in the mountains the burn-off. (139)

When the timber has become tinderbox dry, the villagers of Long Pot form fire brigades and gather near the fields on the chosen day. While the younger men of the village race down the slope igniting the timber as they come, others circle the perimeter, lighting stacked timber and brush on the edge of the field. The burn-off not only serves the purpose of removing fallen timber from the field, but it also leaves a valuable layer of ash, which contains phosphate, calcium, and potassium, scattered evenly across the field. (140)

Even though the fields are ready for planting as soon as the burn-off is completed, the poppy's annual cycle dictates that its planting be delayed until September. If the land is left unplanted, however, it loses valuable minerals through erosion and becomes covered with a thick crop of weeds. Here it might seem logical to plant dry upland rice, but since rice is not harvested until November, two months after the poppies should have been planted, the Meo instead plant a hardy variety of mountain corn that is harvested in August and early September. The corn keeps the ground clear of weeds during the summer, and provides fodder for the menagerie of hogs, mountain ponies, chickens, and cows whose wanderings turn Long Pot village into a sea of mud every rainy season. (141)

Once the corn has been picked in August and early September, Meo women begin chopping and turning the soil with a heavy, triangular hoe. Just before the poppy seeds are sown broadcast across the surface of the ground in September, the soil must be chopped fine and raked smooth with a bamboo broom. In November women thin out the poppies, leaving the healthier plants standing about six inches apart. At the same time tobacco, beans, spinach, and other vegetables are planted among the poppies; they add minerals to the soil and supplement the Meo diet. (142)

The poppies are thinned again in late December and several weeks later the vegetables are picked, clearing the ground and allowing the poppy to make its final push. By January the bright red and white poppy flowers will start to appear and the harvest will begin, as the petals drop away exposing an egg shaped bulb containing the resinous opium. Since most farmers stagger their plantings to minimize demands on their time during the busy harvest season and reduce the threat of weather damage, the harvest usually continues until late February or early March. (143)

To harvest the opium, Meo farmers tap the poppy's resin much like a Vermont maple sugar farmer or a Malaysian rubber farmer harvest their crops. An opium farmer holds the flower's egg-sized bulb with the fingers of one hand while he uses a three-bladed knife to incise shallow, longitudinal slits on its surface. The cuttings are made in the cool of the late afternoon. During the night the opium resin oozes out of the bulb and collects on its surface. Early the next morning, before the sun drys the moist sap, a Meo woman scrapes the surface of the bulb with a flexible rectangular blade and deposits the residue in a cup hanging around her neck. When she has finished harvesting a kilo of the dark, sticky sap she wraps it in banana leaves and ties the bundle with string.

By the time the harvest is finished, the forty-seven households in Long Pot village have collected more than seven hundred kilos of raw opium. (144) Since Golden Triangle opium is usually 10 percent morphine by weight, the Long Pot harvest will yield roughly seventy kilos of pure morphine base after it has been boiled, processed, and pressed into bricks. Once the morphine has been chemically bonded with acetic anhydride in one of the region's many heroin laboratories, Long Pot's innocent opium harvest becomes seventy kilos of high grade no. 4 heroin.

While international criminal syndicates reap enormous profits from the narcotics traffic, the Meo farmers are paid relatively little for their efforts. Although opium is their sole cash crop and they devote most of their effort to it, Meo farmers only receive $400 to $600 for ten kilos of raw opium. After the opium leaves the village, however, the value of those ten kilos begins to spiral upward, Ten kilos of raw opium yield one kilo of morphine base worth $500' in the Golden Triangle. After being processed into heroin, one kilo of morphine base becomes one kilo of no. 4 heroin worth $2,000 to $2,500 in Bangkok. In San Francisco, Miami, or New York, the courier delivering a kilo of heroin to a wholesaler receives anywhere from $18,000 to $27,000. Diluted with quinine or milk sugar, packaged in forty-five thousand tiny gelatin capsules and sold on the streets for $5 a shot, a kilo of heroin that began as $500 worth of opium back in Long Pot is worth $225 '000. (145)

In the 1950's Long Pot's farmers had sold their opium to Chinese caravans from the Plain of Jars that passed through the area several times during every harvest season. Despite the occupation of the plain by neutralist and Pathet Lao forces in 1960 and 1961, Chinese caravans kept coming and opium growers in Long Pot District continued to deal with them.

According to Long Pot's district officer, Ger Su Yang, the Chinese merchant caravans disappeared after the 1964-1965 harvest, when heavy fighting broke out on the plain's western perimeter, But they were replaced by Meo army caravans from Long Tieng. Commanded by lieutenants and captains in Vang Pao's army, the caravans usually consisted of half a dozen mounted Meo soldiers and a string of shaggy mountain ponies loaded with trade goods. When the caravans arrived from Long Tieng they usually stayed at the district officer's house in Long Pot village and used it as a headquarters while trading for opium in the area. Lao Theung and Meo opium farmers from nearby villages, such as Gier Goot and Thong Oui, carried their opium to Long Pot and haggled over the price with the Meo officers in the guest corner of Ger Su Yang's house. (146) While the soldiers weighed the opium on a set of balance scales and burned a small glob to test its morphine content (a good burn indicates a high morphine content), the farmer inquired about the price and examined the trade goods spread out on the nearby sleeping platform (medicines, salt, iron, silver, flashlights, cloth, thread, etc.). After a few minutes of carefully considered offers and counteroffers, a bargain was struck. At one time the Meo would accept nothing but silver or commodities. However, for the last decade Air America has made commodities so readily available that most opium farmers now prefer Laotian government currency. (Vang Pao's Meo subjects are unique in this regard. Hill tribesmen in Burma and Thailand still prefer trade goods or silver in the form of British India rupees, French Indochina piasters, or rectangular bars.) (147)

To buy up opium from the outlying areas, the Meo soldiers would leave Long Pot village on short excursions, hiking along the narrow mountain trails to Meo and Lao Theung villages four or five miles to the north and south. For example, the headman of Nam Suk, a Lao Theung village about four miles north of Long Pot, recalls that his people began selling their opium harvest to Meo soldiers in 1967 or 1968. Several times during every harvest season, five to eight of them arrived at his village, paid for the opium in paper currency, and then left with their purchases loaded in backpacks. Previously this village had sold its opium to Lao and Chinese merchants from Vang Vieng, a market town on the northern edge of the Vientiane Plain. But the Meo soldiers were paying 20 percent more, and Lao Theung farmers were only too happy to deal with them. (148)

Since Meo soldiers paid almost sixty dollars a kilo, while merchants from Vang Vieng or Luang Prabang only paid forty or fifty dollars, Vang Pao's officers were usually able to buy up all of the available opium in the district after only a few days of trading. Once the weight of their purchases matched the endurance limits of their rugged mountain ponies, the Meo officers packed it into giant bamboo containers, loaded it on the ponies and headed back for Long Tieng, where the raw opium was refined into morphine base. Meo army caravans had to return to Long Pot and repeat this procedure two or three times during every season before they had purchased the district's entire opium harvest.

However, during the 1969-1970 opium harvest the procedure changed. Long Pot's district officer, Ger Su Yang, described this important development in an August 19, 1971, interview:

"Meo officers with three or four stripes [captain or major] came from Long Tieng to buy our opium. They came in American helicopters, perhaps two or three men at one time. The helicopter leaves them here for a few days and they walk to villages over there [swinging his arm in a semicircle in the direction of Gier Goot, Long Makkhay and Nam Pac], then come back here and radioed Long Tieng to send another helicopter for them. They take the opium back to Long Tieng.

Ger Su Yang went on to explain that the helicopter pilots were always Americans, but it was the Meo officers who stayed behind to buy up the opium. The headman of Nam Ou, a Lao Theung village five miles north of Long Pot, confirmed the district officer's account; he recalled that in 1969-1970 Meo officers who had been flown into Tam Son village by helicopter hiked into his village and purchased the opium harvest. Since the thirty households in his village only produced two or three kilos of opium apiece, the Meo soldiers continued on to Nam Suk and Long Pot." (149)

Although Long Pot's reluctant alliance with Vang Pao and the CIA at first brought prosperity to the village, by 1971 it was weakening the local economy and threatening Long Pot's very survival. The alliance began in 1961 when Meo officers visited the village, offering money and arms if they joined with Vang Pao and threatening reprisals if they remained neutral. Ger Su Yang resented Vang Pao's usurpation of Touby Lyfoung's rightful position as leader of the Meo, but there seemed no alternative to the village declaring its support for Vang Pao. (150) During the 1960's Long Pot had become one of Vang Pao's most loyal villages. Edgar Buell devoted a good deal of his personal attention to winning the area over, and USAID even built a school in the village. (151) In exchange for sending less than twenty soldiers to Long Tieng, most of whom were killed in action, Long Pot village received regular rice drops, money, and an excellent price for its opium.

But in 1970 the war finally came to Long Pot. With enemy troops threatening Long Tieng and his manpower pool virtually exhausted, Vang Pao ordered his villages to send every available man, including even the fifteen-year-old's. Ger Su Yang complied, and the village built a training camp for its sixty recruits on a nearby hill. Assisted by Meo officers from Long Tieng, Ger Su Yang personally supervised the training, which consisted mainly of running up and down the hillside. After weeks of target practice and conditioning, Air America helicopters began arriving late in the year and flew the young men off to battle.

Village leaders apparently harbored strong doubts about the wisdom of sending off so many of their young men, and as early rumors of heavy casualties among the recruits filtered back, opposition to Va g Pao's war stiffened. When Long Tieng officials demanded more recruits in January 1971 the village refused. Seven months later Ger Su Yang expressed his determination not to sacrifice any more of Long Pot's youth:

"Last year I sent sixty [young men] out of this village. But this year it's finished. I can't send any more away to fight.... The Americans in Long Tieng said I must send all the rest of our men. But I refused. So they stopped dropping rice to us. The last rice drop was in February this year." (152)

In January Long Tieng officials warned the village that unless recruits were forthcoming Air America's rice drops would stop. Although Long Pot was almost totally dependent on the Americans for its rice supply, hatred for Vang Pao was now so strong that the village was willing to accept the price of refusal. "Vang Pao keeps sending the Meo to be killed," said Ger Su Yang. "Too many Meo have been killed already, and he keeps sending more. Soon all will be killed. but Vang Pao doesn't care." But before stopping the shipments Long Tieng officials made a final offer. "If we move our village to Ban Son or Tin Bong [another resettlement area] the Americans will give us rice again," explained Ger Su Yang. "But at Ban Son there are too many Meo, and there are not enough rice fields. We must stay here, this is our home."153

When the annual Pathet Lao-North Vietnamese offensive began in January 1971, strong Pathet Lao patrols appeared in the Long Pot region for the first time in several years and began making contact with the local population. Afraid that the Meo and Lao Theung might go over to the Pathet Lao, the Americans ordered the area's residents to move south and proceeded to cut off rice support for those who refused to obey. (154) A far more powerful inducement was added when the air war bombing heated up to the east of Long Pot District and residents became afraid that it would spread to their villages. To escape from the threat of being bombed, the entire populations of Phou Miang and Muong Chim, Meo villages five miles east of Long Pot, moved south to the Tin Bong resettlement area in early 1971. At about the same time, many of the Meo residents of Tam Son and eight families from Long Pot also migrated to Tin Bong. Afraid that Pathet Lao patrols operating along Route 13 might draw air strikes on their villages, the Meo of Sam Poo Kok joined the rush to Tin Bong, while three Lao Theung villages in the same general area-Nam Suk, Nam Ou and San Pakau-moved to a ridge opposite Long Pot village. Their decision to stay in Long Pot District rather than move south was largely due to the influence of Ger Su Yang. Determined to remain in the area, he used all his considerable prestige to stem the tide of refugees and retain enough population to preserve some semblance of local autonomy. Thus rather than moving south when faced with the dual threat of American air attacks and gradual starvation, most of the villagers abandoned their houses in January and hid in the nearby forest until March.

While U.S. officials in Laos claim that hill tribes move to escape slaughter at the hands of the enemy, most of the people in Long Pot District say that it is fear of indiscriminate American and Laotian bombing that has driven their neighbors south to Tin Bong. These fears cannot be dismissed as ignorance on the part of "primitive" tribes; they have watched the air war at work and they know what it can do. From sunrise to sunset the mountain silence is shattered every twenty or thirty minutes by the distant roar of paired Phantom fighters enroute to targets around the Plain of Jars. Throughout the night the monotonous buzz of prowling AC-47 gunships is broken only when their infrared sensors sniff warm mammal flesh and their miniguns clatter, spitting out six thousand rounds a minute. Every few days a handful of survivors fleeing the holocaust pass through Long Pot relating their stories of bombing and strafing. On August 21, 1971, twenty exhausted refugees from a Lao Theung village in the Muong Soui area reached Long Pot village. Their story was typical. In June Laotian air force T-28's bombed their village while they fled into the forest. Every night for two months AC-47 gunships raked the ground around their trenches and shallow caves. Because of the daylight bombing and nighttime strafing, they were only able to work their fields in the predawn hours. Finally, faced with certain starvation, they fled the Pathet Lao zone and walked through the forest for eleven days before reaching Long Pot. Twice during their march the gunships found them and opened fire. (155)

When Ger Su Yang was asked which he feared most, the bombing or the Pathet Lao, his authoritative confidence disappeared and he replied in an emotional, quavering voice, The bombs! The bombs! Every Meo village north of here [pointing to the northeast] has been bombed. Every village! Everything! There are big holes [extending his arms] in every village. Every house is destroyed. If bombs didn't hit some houses they were burned. Everything is gone. Everything from this village, all the way to Muong Soui and all of Xieng Khouang [Plain of Jars] is destroyed. In Xieng Khouang there are bomb craters like this [stretching out his arm, stabbing into the air to indicate a long line of craters] all over the plain. Every village in Meng Khouang has been bombed, and many, many people died. From here . . all the mountains north have small bombs in the grass. They were dropped from the airplanes.(156)

Although opium production in Long Pot village had not yet declined, by August 1971 there was concern that disruption caused by the escalating conflict might reduce the size of the harvest. Even though the village spent the 1970-1971 harvest season hiding in the forest, most families somehow managed to attain their normal output of fifteen kilos. Heavy fighting at Long Tieng delayed the arrival of Air America helicopters by several months, but in May 1971 they finally began landing at Long Pot carrying Meo army traders, who paid the expected sixty dollars for every kilo of raw opium. (157)

However, prospects for the 1971-1972 opium harvest were looking quite dismal as planting time approached in late August. There were plenty of women to plant, weed, and harvest, but a shortage of male workers and the necessity of hiding in the forest during the past winter had made it difficult for households to clear new fields. As a result, many farmers were planting their poppies in exhausted soil, and they only expected to harvest half as much opium as the year before.

However, as the war mounted in intensity through 1971 and early 1972, Long Pot District's opium harvest was drastically reduced and eventually destroyed. U.S.A.I.D officials reported that about forty-six hundred hill tribesmen had left the district in January and February 1971 and moved to the Tin Bong refugee area to the south, where there was a shortage of land. (158) Some of the villages that remained, such as the three Lao Theung villages near Long Pot village, were producing no opium at all. Even Long Pot village had lost eight of its households during the early months of 1971. Finally, on January 4, 1972, Allied fighter aircraft attacked Long Pot District. In an apparent attempt to slow the pace of a Pathet Lao offensive in the district, the fighters napalmed the district's remaining villages, destroying Long Pot village and the three nearby Lao Theung villages. (159)

Gen. Ouane Rattikone could not have foreseen the enormous logistical problem that

would be created by his ill-timed eviction of the Corsican charter airlines in 1965. While

use of Air America aircraft solved the problem for Gen. Vang Pao by flying Meo opium

out of northeastern Laos, in the northwest Ouane had to rely on his own resources. Eager

to establish an absolute monopoly over Laos's drug traffic, he had been confident of

being able to expropriate two or three C-47's from the Laotian air force to do the job. But

because of the intensification of the fighting in 1964-1965, Ouane found himself denied

access to his own military aircraft. Although he still had control over enough civilian air

transport to carry the local harvest and some additional Burmese imports, he could hardly

hope to tap a major portion of Burma's exports unless he gained control over two or three

air force C-47 transports. General Ouane says that in 1964 he purchased large quantities

of Burmese opium from the caravans that entered Laos through the Ban Houei Sai region

in the extreme northwest, but claims that because of his transportation problem no large

Shan or Nationalist Chinese opium caravans entered northwestern Laos in 1965. (160)

Gen. Ouane Rattikone could not have foreseen the enormous logistical problem that

would be created by his ill-timed eviction of the Corsican charter airlines in 1965. While

use of Air America aircraft solved the problem for Gen. Vang Pao by flying Meo opium

out of northeastern Laos, in the northwest Ouane had to rely on his own resources. Eager

to establish an absolute monopoly over Laos's drug traffic, he had been confident of

being able to expropriate two or three C-47's from the Laotian air force to do the job. But

because of the intensification of the fighting in 1964-1965, Ouane found himself denied

access to his own military aircraft. Although he still had control over enough civilian air

transport to carry the local harvest and some additional Burmese imports, he could hardly

hope to tap a major portion of Burma's exports unless he gained control over two or three

air force C-47 transports. General Ouane says that in 1964 he purchased large quantities

of Burmese opium from the caravans that entered Laos through the Ban Houei Sai region

in the extreme northwest, but claims that because of his transportation problem no large

Shan or Nationalist Chinese opium caravans entered northwestern Laos in 1965. (160)

Shortly after Gen. Phoumi Nosavan fled to Thailand in February 1965, General Ouane's

political ally, General Kouprasith, invited the commander of the Laotian air force, Gen.

Thao Ma, to Vientiane for a friendly chat. Gen. Thao Ma recalls that he did not learn the

purpose of the meeting until he found himself seated at lunch with General Ouane,

General Kouprasith, and Gen. Oudone Sananikone. Gen. Kouprasith leaned forward and,

with his friendliest smile, asked the diminutive air force general, "Would you like to be

rich?" Thao Ma replied, "Yes. Of course." Encouraged by this positive response, General

Kouprasith proposed that he and General Ouane pay Thao Ma I million kip ($2,000) a

week and the air force allocate two C-47 transports for their opium-smuggling ventures.

To their astonishment, Thao Ma refused; moreover, he warned Kouprasith and Ouane that if they tried to bribe any of his transport pilots he would personally intervene and put

a stop to it. (161)

Shortly after Gen. Phoumi Nosavan fled to Thailand in February 1965, General Ouane's

political ally, General Kouprasith, invited the commander of the Laotian air force, Gen.

Thao Ma, to Vientiane for a friendly chat. Gen. Thao Ma recalls that he did not learn the

purpose of the meeting until he found himself seated at lunch with General Ouane,

General Kouprasith, and Gen. Oudone Sananikone. Gen. Kouprasith leaned forward and,

with his friendliest smile, asked the diminutive air force general, "Would you like to be

rich?" Thao Ma replied, "Yes. Of course." Encouraged by this positive response, General

Kouprasith proposed that he and General Ouane pay Thao Ma I million kip ($2,000) a

week and the air force allocate two C-47 transports for their opium-smuggling ventures.

To their astonishment, Thao Ma refused; moreover, he warned Kouprasith and Ouane that if they tried to bribe any of his transport pilots he would personally intervene and put

a stop to it. (161)

Very few Laotian generals would have turned down such a profitable offer, but Gen. Thao Ma was one of those rare generals who placed military considerations ahead of his political career or financial reward. As the war in South Vietnam and Laos heated up during 1964, Laotian air force T-28's became the key to clandestine air operations along the North Vietnamese border and the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Gen. Thao Ma took personal command of the squadrons bombing the Ho Chi Minh Trail and providing close air support for Secret Army operations in the northeast. (162) But his proudest accomplishment was the invention of an early version of what later became the AC-47 gunship. Aware that the Pathet Lao often attacked at night when his T-28 fighters were grounded, Thao Ma began looking for a way to provide nighttime air support for government forces and came up with the idea of arming his C-47 transports with .50 caliber machine guns. In 1964 he reduced the air force's logistic capacity by converting a number of his transports into gunships. Thus, when Kouprasith and Ouane demanded two C-47's in early 1965, Thao Ma felt there were none to spare and refused. (163)

Despite further offers and heavy political pressure, Thao Ma's intransigence continued. In 1966 Ouane was still without access to air transport and again no major Shan or Nationalist Chinese opium caravans entered northwestern Laos. Evidently the economic loss of two successive Burmese opium harvests, and the dire prospect of continued losses, convinced Ouane and Kouprasith that the Laotian air force badly needed a new commander.

In May 1966 Gen. Thao Ma was summoned to Vientiane from his headquarters in Savannakhet for a harsh dressing down by the high command. The transport section of the air force was severed from his command and he was ordered to move his headquarters to Vientiane. (164) Fearing assassination at the hands of General Kouprasith if he moved to Vientiane, Thao Ma appealed for a six-month delay and began spending most of his time at the air base in Luang Prabang. (165) As the transfer date approached, Thao Ma sought desperately for an alternative. He begged the Americans, Capt. Kong Le, and the king to intercede on his behalf, but to no avail. (166) Friend and foe alike report that he was in a state of near panic by October, and Thao Ma himself remembers that he was functioning in a dazed stupor. (167) Thus, a coup seemed his only way out.

At 7:00 A.M. on October 22, six T-28 fighters took off from Savannakliet and headed north for Vientiane. At 8:20 A.M. the squadron reached the Laotian capital and the first bomb scored a direct hit on General Kouprasith's office at general staff headquarters. The T-28's strafed and bombed the headquarters compound extensively. Two munitions dumps at Wattay Airport on the outskirts of Vientiane were destroyed. The squadron also rocketed General Kouprasith's home at Chinaimo army camp, but all the missiles were wide of the mark and the general was unharmed. (168) Over thirty people were killed and dozens more were wounded. (169)

The squadron flew back to Savarmakhet, and Vientiane waited nervously for a second round of attacks. After receiving numerous appeals from both Lao and American officials to end his revolt and go into exile, Gen. Thao Ma and ten of his best pilots took off from Savannakhet at 1:45 A.M. October 23, and flew to Thailand, where they were granted political asylum. (170)

Although his coup was primarily an act of revenge, Thao Ma had apparently expected

that his friend Kong Le, the neutralist army general, would seize Vientiane and oust the

generals once Kouprasith was dead. (171) However, Kong Le was having his own

problems with Kouprasith and, unknown to Thao Ma, had left for Bangkok five days

before to meet with CIA officials. Shortly after the T-28's struck Vientiane, Thai officials

placed Kong Le under house arrest in Bangkok and Kouprasith ordered Laotian border

guards to arrest him if he tried to return. Kong Le became a political exile in Paris, and

his neutralist army fell under rightist control. (172) Soon after Thao Ma flew into exile, a

pliant, right-wing general was appointed air force commander.

Although his coup was primarily an act of revenge, Thao Ma had apparently expected

that his friend Kong Le, the neutralist army general, would seize Vientiane and oust the

generals once Kouprasith was dead. (171) However, Kong Le was having his own

problems with Kouprasith and, unknown to Thao Ma, had left for Bangkok five days

before to meet with CIA officials. Shortly after the T-28's struck Vientiane, Thai officials

placed Kong Le under house arrest in Bangkok and Kouprasith ordered Laotian border

guards to arrest him if he tried to return. Kong Le became a political exile in Paris, and

his neutralist army fell under rightist control. (172) Soon after Thao Ma flew into exile, a

pliant, right-wing general was appointed air force commander.

With an ample supply of C-47 transports and helicopters now assured, General Ouane

proceeded to contact Chinese and Shan opium brokers in the tri-border area, and placed a

particularly large order with a fast rising young Shan warlord named Chan Shee-fu. (173)

As the Lahu and Wa hill tribes of northeastern Burma finished harvesting opium in the

early months of 1967, Chan Shee-fu's traders and brokers began buying up all the opium

they could find. By June he had assembled one of the largest single shipments on

record sixteen tons of raw opium. When the caravan set out across the rugged Shan

highlands for its destination near Ban Houei Sai, Laos, about two hundred miles away, its

three hundred pack horses and five hundred armed guards marched single file in a

column that extended over a mile along the narrow mountain trails.

With an ample supply of C-47 transports and helicopters now assured, General Ouane

proceeded to contact Chinese and Shan opium brokers in the tri-border area, and placed a

particularly large order with a fast rising young Shan warlord named Chan Shee-fu. (173)

As the Lahu and Wa hill tribes of northeastern Burma finished harvesting opium in the

early months of 1967, Chan Shee-fu's traders and brokers began buying up all the opium

they could find. By June he had assembled one of the largest single shipments on

record sixteen tons of raw opium. When the caravan set out across the rugged Shan

highlands for its destination near Ban Houei Sai, Laos, about two hundred miles away, its

three hundred pack horses and five hundred armed guards marched single file in a

column that extended over a mile along the narrow mountain trails.

But this monumental caravan was to spark off a bloody confrontation that made headlines all over the world as the " 1967 Opium War." While the war in the papers struck most readers as a colorful anachronism, the war in reality was a struggle for control of Burma's opium exports, which at that time amounted to about five hundred tons of raw opium annually-more than one-third of the world's total illicit supply. Consequently, each group's share of Burma's opium exports and its role in the Golden Triangle's heroin trade were largely determined by the war and its aftermath. All of the combatants were well aware of what was at stake, and threw everything they could muster into the battle.

The confrontation started off with the K.M.T (Nationalist Chinese army units) based in northern Thailand deciding to send more than a thousand soldiers into Burma to head off Chan Shee-fu's caravan. The K.M.T had been worried for some time that the rising young Shan warlord might threaten their fifteen-year domination of the opium trade, and this mammoth caravan was a serious threat. But the Shan caravan eluded Nationalist Chinese forces, fled across the Mekong into Laos, and dug in for a fight at Ban Khwan, a lumber town twenty miles northwest of Ban Houei Sai. After several days of indecisive fighting between he Chinese and Shans, Gen. Ouane Rattikone entered the lists. Displaying an aggressiveness rare among Laotian army commanders, General Ouane bombed both sides with a squadron of T-28's and swept the field of battle with the Second Paratroop Battalion. While his friends and enemies fled in disorder, General Ouane's troops scooped up the sixteen tons of raw opium and delivered it to the victorious general, presumably free of charge. Almost two hundred people, mainly Shans and Chinese, died in the fighting.

As a result of General Ouane's victory, the K.M.T lost many of it's profitable prerogatives to the general. They had nevertheless crushed Chan Shee-fu's bid for supremacy, even though they had not completely destroyed him. After the battle General Ouane emerged as one of the most, important heroin manufacturers in the Golden Triangle, since his share of the Burmese opium trade increased considerably.

Although it was a relatively minor military action compared to the battles raging elsewhere in Indochina, the 1967 Opium War captured the imagination of the American press. However, all of the accounts studiously avoided any serious discussion of the Golden Triangle opium trade, and emphasized the sensational. Using a cliche-studded prose usually reserved for the sports page or travel section, the media rambled on about wild animals, primitive tribes, desperadoes of every description, and the mysterious ways of the Orient. But despite its seductively exotic aspects, the 1967 Opium War remains the most revealing episode in the recent history of the Golden Triangle opium trade.

After the abolition of government opium monopolies in the 1940's and 1950's, the Golden Triangle's drug trade disappeared behind the velvet curtain of government secrecy and it became increasingly difficult to verify official involvement or the extent of the traffic. Suddenly the curtain was snatched back, and there were eighteen hundred of the distinguished General Ouane's best troops battling fourteen hundred well-armed Nationalist Chinese soldiers (supposedly evacuated to Taiwan six years before) for sixteen tons of opium. But an appreciation of the subtler aspects of this sensational battle requires some background on the economic activities of the K.M.T units based in Thailand, the Shan rebels in Burma, and in particular, the long history of CIA operations in the Golden Triangle area.

Afraid that the Communists were about to overrun all of Nam Tha Province, the CIA

assigned William Young to the area in mid 1962. Young was instructed to build up a hill

tribe commando force for operations in the tri-border area since regular Laotian army

troops were ill-suited for military operations in the rugged mountains. Nam Tha's ethnic complexity and the scope of clandestine operations made paramilitary work in this

province far more demanding than Meo operations in the northeast. (175)

Afraid that the Communists were about to overrun all of Nam Tha Province, the CIA

assigned William Young to the area in mid 1962. Young was instructed to build up a hill

tribe commando force for operations in the tri-border area since regular Laotian army

troops were ill-suited for military operations in the rugged mountains. Nam Tha's ethnic complexity and the scope of clandestine operations made paramilitary work in this

province far more demanding than Meo operations in the northeast. (175)

Nam Tha Province probably has more different ethnic minorities per square mile than any other place on earth, having been a migration crossroads for centuries for tribes from southern China and Tibet. Successive waves of Meo and Yao tribesmen began migrating down the Red River valley into North Vietnam in the late 1700's, reaching Nam Tha in the mid nineteenth century. (176) Nam Tha also marks the extreme southeastern frontier for advancing Tibeto-Burman tribes, mainly Akha and Lahu, who have been moving south, with glacierlike speed, through the China-Burma borderlands for centuries. Laotian officials believe that there may be as many as thirty different ethnic minorities living in the province.

Nam Tha Province itself was tacked onto Laos in the late nineteenth century when Europe's imperial real estate brokers decided that the Mekong River was the most convenient dividing line between British Burma and French Indochina. Jutting awkwardly into Thailand, Burma, and China, it actually looks on maps as if it had been pasted onto Laos. There are very few Lao in Nam Tha, and most of the lowland valleys are inhabited by Lu, a Tai peaking people who were once part of a feudal kingdom centered in southern Yunnan.

With thirty tribal dialects and languages, most of them mutually unintelligible, and virtually no Lao population, Nam Tha Province had been a source of endless frustration for both French and American counterinsurgency specialists.

With his knowledge of local languages and his remarkable rapport with the mountain minorities, William Young was uniquely qualified to overcome these difficulties. Speaking four of the most important languages-Lu, Lao, Meo, and Lahu,Young could deal directly with most of the tribesmen in Nam Tha. And since Young had grown up in Lahu and Shan villages in Burma, he actually enjoyed the long months of solitary work among the hill tribes, which might have strained the nerves of less acculturated agents. Rather than trying to create a tribal warlord on the Vang Pao Young decided to build a pan-tribal army under the command of a joint council composed of one or two leaders from every tribe. Theoretically the council was supposed to have final authority on all matters, but in reality Young controlled all the money and made all the decisions. However, council meetings did give various tribal leaders a sense of participation and greatly increased the efficiency of paramilitary operations. Most importantly, Young managed to develop his pan-tribal council and weaken the would-be Yao warlord, Chao Mai, without alienating him from the program. In fact, Chao Mai remained one of Young's strongest supporters, and his Yao tribesmen comprised the great majority of the CIA mercenary force in Nam Tha. (177)

Although his relationships with hill tribe leaders were quite extraordinary, William Young still used standard CIA procedures for "opening up" an area to paramilitary operations. But to organize the building of runways, select base sites, and perform all the other essential tasks connected with forging a counter guerrilla infrastructure, Young recruited a remarkable team of sixteen Shan and Lahu operatives he called "the Sixteen Musketeers," whose leader was a middle-aged Shan nationalist leader, "General" U Ba Thein. (178)

With the team's assistance, Young began "opening up" the province in mid 1962. By late

1963 he had built up a network of some twenty dirt landing strips and a guerrilla force of

six hundred Yao commandos and several hundred additional troops from the other tribes.

But the war in northwestern Laos had intensified and large-scale refugee relocation's had

begun in late 1962 when Chao Mai and several thousand of his Yao followers abandoned

their villages in the mountains between Nam Tha City and Muong Sing, both of Which

were under Pathet Lao control, and moved south to Ban Na Woua and Nam Thouei,

refugee centers established by the Sixteen Musketeers. (179) (See Map 9, page 303, for

locations of

these towns.)

The outbreak of

fighting several

months later

gradually

forced tribal

mercenaries

and their

families,

particularly the

Yao, out of the

Pathet Lao

zone and into

refugee camps.

(180)

With the team's assistance, Young began "opening up" the province in mid 1962. By late

1963 he had built up a network of some twenty dirt landing strips and a guerrilla force of

six hundred Yao commandos and several hundred additional troops from the other tribes.

But the war in northwestern Laos had intensified and large-scale refugee relocation's had

begun in late 1962 when Chao Mai and several thousand of his Yao followers abandoned

their villages in the mountains between Nam Tha City and Muong Sing, both of Which

were under Pathet Lao control, and moved south to Ban Na Woua and Nam Thouei,

refugee centers established by the Sixteen Musketeers. (179) (See Map 9, page 303, for

locations of

these towns.)

The outbreak of

fighting several

months later

gradually

forced tribal

mercenaries

and their

families,

particularly the

Yao, out of the

Pathet Lao

zone and into

refugee camps.

(180)

Instead of directing rice drops and refugee operations personally, Young delegated the responsibility to a pistol packing community development worker named Joseph Flipse (who, like Edgar Buell, was an IVS volunteer). While Flipse maintained a humanitarian showplace at Nam Thouei complete with a hospital, school, and supply warehouse, William Young and the Sixteen Musketeers opened a secret base at Nam Yu, only three miles away, which served as CIA headquarters for cross-border intelligence forays deep into southern China. (181)

The Dr. Jekyll-Mr. Hyde relationship between Nam Thouei and Nam Yu in northwestern Laos was very similar to the arrangement at Sam Thong and Long Tieng in northeastern Laos: for almost a decade reporters and visiting Congressmen were taken to Sam Thong to see all the wonderful things Edgar Buell was doing to save the poor Meo from Communist genocide, but were flatly denied access to CIA headquarters at Long Tieng. (182) However, just as the operations were getting under way, CIA policy decisions and local opium politics combined to kill this enthusiasm and weaken the overall effectiveness of bill tribe operations. A series of CIA personnel transfers in 1964 and 1965 probably did more damage than anything else. When Young became involved in a heated jurisdictional dispute with Thai intelligence officers in October 1964, the CIA pulled him out of Nam Tha and sent him to Washington, D.C., for a special training course. High-ranking CIA bureaucrats in Washington and Vientiane had long been dissatisfied with the paucity of "Intel-Coms" (intelligence communications) and in-depth reports they were getting from Young, and apparently used his squabble with the Thais as a pretext for placing a more senior agent in charge of operations in Nam Tha. After Young's first replacement, an operative named Objibway, died in a helicopter crash in the summer of 1965, Anthony Poe drew the assignment. (183)

Where William Young had used his skill as a negotiator and his knowledge of minority

cultures to win compliance from hill tribe leaders, Anthony Poe preferred to use bribes,

intimidation, and threats. The hill tribe leaders, particularly Chao Mai, were alienated by

Poe's tactics and became less aggressive. Poe tried to rekindle their enthusiasm for

combat by raising salaries and offering cash bonuses for Pathet Lao ears. (184) But as a

former U.S.A.I.D official put it, "The pay was constantly going up, and the troops kept

moving slower." (185)

Where William Young had used his skill as a negotiator and his knowledge of minority

cultures to win compliance from hill tribe leaders, Anthony Poe preferred to use bribes,

intimidation, and threats. The hill tribe leaders, particularly Chao Mai, were alienated by

Poe's tactics and became less aggressive. Poe tried to rekindle their enthusiasm for

combat by raising salaries and offering cash bonuses for Pathet Lao ears. (184) But as a

former U.S.A.I.D official put it, "The pay was constantly going up, and the troops kept

moving slower." (185)

Gen. Ouane Rattikone's monopolization of the opium trade in Military Region 1, northwestern Laos, dealt another major blow to Chao Mai's enthusiasm for the war effort. Chao Mai had inherited control over the Yao opium trade from his father, and during the early 1960's he was probably the most important opium merchant in Nam Tha Province. Every year Chao Mai sold the harvest to the Chinese merchants in Muong Sing and Ban Houei Sai who acted as brokers for the Corsican charter airlines. With his share of the profits, Chao Mai financed a wide variety of social welfare projects among the Yao,. from which he derived his power and prestige. However, when General Ouane took over the Laotian opium trade in 1965, he forced all of his competitors, big and little, out of business. One U.S.A.I.D official who worked in the area remembers that all the hotels and shops in Ban Houci Sai were crowded with opium buyers from Vientiane and Luang Prabang following the 1963 and 1964 harvest seasons. But in 1965 the hotels and shops were empty and local merchants explained that, "there was a big move on by Ouane to consolidate the opium business." General Ouane's strategy for forcing his most important competitor out of business was rather simple-, after Chao Mai had finished delivering most of the Yao opium to General Ouane's broker in Ban Houei Sai, who had promised to arrange air transport to Vientiane, the Lao army officer simply refused to pay for the opium. There was absolutely nothing Chao Mai could do, and he was forced to accept the loss. Needless to say, this humiliating incident further weakened his control over the Yao, and by the time he died in April 1967 most of his followers had moved to Nam Keung where his brother Chao La was sitting out the war on the banks of the Mekong. (186)

After Chao Mai's death, Anthony Poe tried in vain to revitalize tribal commando operations by appointing his brother, Chao La, commander of Yao paramilitary forces. Although Chao La accepted the position and participated in the more spectacular raids, such as the recapture of Nam Tha city in October 1967, he has little interest in the tedium of day-to-day operations which are the essence of counter-guerrilla warfare. Unlike Chao Mai, who was a politician and a soldier, Chao La is a businessman whose main interests are his lumber mill, gunrunning and the narcotics traffic. In fact, there are some American officials who believe that Chao La only works with the CIA to get guns (which he uses to buy opium from Burmese smugglers) and political protection for his opium refineries. (187)

Although William Young was removed from command of paramilitary operations in 1964, the CIA had ordered him back to Nam Tha in August 1965 to continue supervising the Yao and Lahu intelligence teams, which were being sent deep into Yunnan Province, China. Wedged between China and Burma, Nam Tha Province is an ideal staging ground for cross-border intelligence patrols operating in southern China. The arbitrary boundaries between Burma, China, and Laos have absolutely no meaning for the hill tribes, who have been moving back and forth across the frontiers for centuries in search of new mountains and virgin forests, As a result of these constant migrations, many of the hill tribes that populate the Burma-China borderlands are also found in Nam Tha Province. (188) Some of the elderly Lahu and Yao living in Nam Tha were actually born in Yunnan, and many of the younger generation have relatives there. Most importantly, both of these tribes have a strong sense of ethnic identity, and individual tribesmen view themselves as members of larger Yao and Lahu communities that transcend national boundaries. (189) Because of the ethnic overlap between all three countries, CIA-trained Lahu and Yao agents from Nam Tha could cross the Chinese border and wander around the mountains of Yunnan tapping telephone lines and monitoring road traffic without being detected.

After a year of recruiting and training agents, William Young had begun sending the first Lahu and Yao teams into China in 1963. Since the CIA and the Pentagon were quite concerned about the possibility of Chinese military intervention in Indochina, any intelligence on military activity in southern China was valued and the cross-border operations were steadily expanded. By the time Young quit the CIA in 1967, he had opened three major radio posts within Burma's Shan States, built a special training camp that was graduating thirty-five agents every two months, and sent hundreds of teams deep into Yunnan. While Young's linguistic abilities and his understanding of hill tribe culture had made him a capable paramilitary organizer, it was his family's special relationship with the Lahu that enabled him to organize the cross-border operations. The Sixteen Musketeers who recruited most of the first agents were Lahu, the majority of the tribesmen who volunteered for these dangerous missions were Labu, and all the radio posts inside the Shan States were manned by Lahu tribesmen. (190)

This special relationship with the Lahu tribe dates back to the turn of the century, when the Rev. William M. Young opened an American Baptist Mission in the Shan States at Kengtung City and began preaching the gospel in the marketplace. While the Buddhist townspeople ignored Reverend Young, crowds of curious Lahu tribesmen, who had come down from the surrounding hills to trade in the market, gathered to listen. None of the Lahu were particularly interested in the God named Jesus Christ of which he spoke, but were quite intrigued by the possibility that Reverend Young himself might be God. A popular Lahu prophet had once told his followers:

"We may not see God, no matter how we search for him now. But, when the time is fulfilled, God will search for us and will enter our homes. There is a sign and when it appears, we will know that God is coming. The sign is that white people on white horses will bring us the Scriptures of God." (191)

Reverend Young was a white American, wore a white tropical suit, and like many Baptist missionaries, carried his Bible wherever he went. As word of the White God spread through the hills, thousands of Lahu flocked to Kengtung, where Reverend Young baptized them on the spot. When Reverend Young reported 4,419 baptisms for the year 1905-1906 (an all-time conversion record for the Burma Baptist Mission), mission officials became suspicious and a delegation was sent to investigate. Although the investigators concluded that Reverend Young was pandering to pagan myths, Baptist congregations in the United States were impressed by his statistical success and had already started sending large contributions to "gather in the harvest." Bowing to financial imperatives, the Burma Baptist Mission left the White God free to wander the hills. (192)