Dillon Read & Co. Inc.

And the

Aristocracy of Prison Profits

by Catherine Austin Fitts

Why I Wrote This Article

I made the decision to write Dillon, Read & Co. Inc. and the Aristocracy of Prison Profits while

gardening at a community farm in Montana during the summer of 2005. I had come to

Montana to prototype Solari Investor Circles, private investment partnerships that practice

financial intimacy – investing in people and products that we or our network know and

trust. If we want clean water, fresh food, sustainable infrastructure, sound banks, lawful

companies and healthy communities, we are going to have to finance and govern these

resources ourselves. We cannot invest in the stocks and bonds of large corporations and

governments that are harming our food, water, environment and all living things and then

expect these resources to be available when we need them. Nor can we deposit and do

business with the banks that are bankrupting our government and economy.

Surviving and thriving as a free people depends on creating and transacting with currencies

and investments other than those printed and manipulated by Wall Street and Washington

to the eventual end of our rights and assets.

What I found in Montana, however, was what I have found in communities all across

America. We are so financially entangled in the federal government and large corporations

that we cannot see our complicity in everything we say we abhor. Our social networks are

so interwoven with the institutional leadership – government officials, bankers, lawyers,

professors, foundation heads, corporate executives, investors, fellow alumni – that we dare

not hold our own families, friends, colleagues and neighbors accountable for our very real

financial and operational complicity. While we hate "the system," we keep honoring and

supporting the people and institutions that are implementing the system when we interact

and transact with them in our day-to-day lives. Enjoying the financial benefits and other

perks that come from that intimate support ensures our continued complicity and

contribution to fueling that which we say we hate.

Sitting in the rich dirt among the beautiful vegetables and flowers, I was facing the futility

of trying to craft solutions without some basic consensus about the economic tapeworm

that is killing us and all living things – while we blindly feed the worm. In a world of

economic warfare, we have to see the strategy behind each play in the game. We have to

see the economic tapeworm and how it works parasitically in our lives. A tapeworm injects

chemicals into a host that causes the host to crave what is good for the tapeworm. In

America, we despair over our deterioration, but we crave the next injection of chemicals

from the tapeworm.

With this in mind, I decided to write “Dillon, Read & Co. Inc. and the Aristocracy of

Prison Profits” as a case study designed to help illuminate the deeper system. It details the

story of two teams with two competing visions for America. The first was a vision shared by my old firm on Wall Street – Dillon Read – and the Clinton Administration with the

full support of a bipartisan Congress. In this vision, America's aristocracy makes money by

ensnaring our youth in a pincer movement of drugs and prisons and wins middle class

support for these policies through a steady and growing stream of government funding,

contracts for War on Drugs activities at federal, state and local levels and related stock

profits. This consensus is made all the more powerful by the gush of growing debt used to

bubble the housing and mortgage markets and manipulate the stock, gold and precious

metals markets in the largest pump and dump in history – the pump and dump of the

entire American economy. This is more than a process designed to wipe out the middle

class. This is genocide – a much more subtle and lethal version than ever before

perpetrated by the scoundrels of our history texts.

The second vision was shared by my investment bank in Washington – The Hamilton

Securities Group – and a small group of excellent government employees and leaders who

believed in the power of education, hard work and a new partnership between people, land

and technology. This vision would allow us to pay down public and private debt and create

new business, infrastructure and equity. We believed that new times and new technologies

called for a revival that would permit decentralized efforts to go to work on the hard

challenges upon us – population, environment, resource management and the rapidly

growing cultural gap between the most technologically proficient and the majority of

people.

My hope is that “Dillon, Read & the Aristocracy of Prison Profits” will help you to see the

game sufficiently to recognize the dividing line between two visions. One centralizes

power and knowledge in a manner that tears down communities and infrastructure as it

dominates wealth and shrinks freedom. The other diversifies power and knowledge to

create new wealth through rebuilding infrastructure and communities and nourishing our

natural resources in a way that reaffirms our ancient and deepest dream of freedom.

My hope is that as your powers grow to see the financial game and the true dividing lines,

you will be better able to build networks of authentic people inventing authentic solutions

to the real challenges we face. My hope is that you will no longer invite into your lives and

work the people and organizations that sabotage real change. If enough of us come clean

and hold true to the intention to transform the game, we invite in the magic that comes in

dangerous times.

Yes, there is a better way and, yes, we can create it.

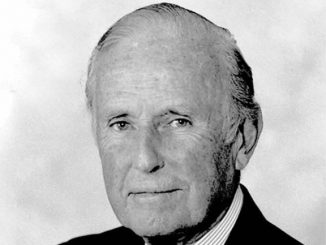

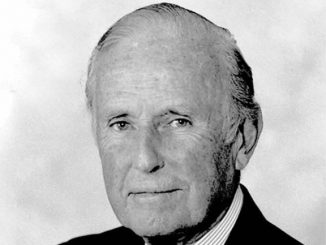

This was a time of transition. Dillon’s Chairman, Nicholas F. Brady, was considered one of George H. W. Bush’s most intimate friends and advisors. Both attended Yale, both were children of privilege. Bush had left his home in Greenwich Connecticut and with the help at his father’s networks at Brown Brothers Harriman had gone into oil and gas in Texas. Brady had gone to Harvard Business School and then returned to the aristocratic hunt country of New Jersey, where the Bradys and the Dillons had estates, to work at Dillon Read.

Bush climbed through Republican politics to become Director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) during the Ford Administration. After spending four years displaced by the Carter Administration, Bush was now Reagan’s Vice President with Executive Order authority for the National Security Council (NSC) and U.S. intelligence and enforcement agencies. Bush’s new authority was married with expanded powers to outsource sensitive work to private contractors. Such work could be funded through the non-transparent financial mechanisms available through the National Security Act of 1947, and the CIA Act of 1949.

This was a secret source of money for funding powerful new weaponry and surveillance technology and operations owned, operated or controlled by private corporations.[3] Carter’s massive layoffs at the CIA had created plenty of private contractor capacity looking for work.[4] An assassination attempt on President Reagan’s life two months after the inauguration meant that Vice President Bush and his team were called on to play an expanded role. Meantime, Nicholas Brady continued as an intimate friend and collaborator from his position as Chairman of Dillon Read.[5]

In April of 1981, Bechtel, working through the Bechtel private venture arm Sequoia, bought the controlling interest in Dillon Read from the Dillon family, led by C. Douglas Dillon, former U.S. Treasury Secretary[6] and son of the firm’s namesake, Clarence Dillon. This was a time when Bechtel was facing increased competition globally while experiencing a decline in the nuclear power business that they had pioneered.[7]

We found ourselves with new owners whose operations were an integral part of the military and intelligence communities and who had demonstrated a rapacious thirst for drinking from the federal money spigot.[8] George Schultz, former Secretary of the Treasury during the Nixon Administration, and now Bechtel executive, joined our board.

Unusual things started to happen that were very “un-Dillon-Ready-like.” First came a new bluntness. I will never forget the day that one of the partners brought around a very charming retired senior Steve Bechtel to tour the firm. Upon introduction, he peered up at me through thick glasses and said “Far out, a chick investment banker.” Then came strategic planning with SRI International, the think tank offshoot of Stanford University that had long standing relationships with the Bechtel family and Schultz. The head of the Energy Group that I worked for at the time was part of the planning group. His mood changed during this period and he later left the firm, retiring from the industry. Before going he warned me that I should do the same. He never said why… leaving a chill that I have felt many times since as ominous changes continue that have no name or a face.

The planning group recommended that we expand our business into merchant banking. This means managing money in venture investment by starting and growing new companies or taking controlling interests in existing companies, including “leveraged buyouts.”[9] Rather than serving companies who needed to raise money by issuing securities, or make markets in existing securities, we were going to start raising money so we could create, buy and trade companies. A company was no longer a customer. They were now a target. Wall Street was its own customer who would raise money to buy companies who would work for us. This required new people with new skills.

A Time Magazine story from December 1981, “The Rothschilds Are Roving” describes a decision by the French Rothschilds in response to the nationalization of Banque Rothschild by President Mitterrand to move significant operations and focus to the U.S. Time reports that they are changing the name of their aggressive venture capital firm, New Court Securities to Rothschild, Inc. and are taking over from the current CEO, John Birkelund.[12]

Birkelund was tall and energetic. He had piercing blue eyes, a driving and hard working ambition and intelligence. He seemed frustrated by the process of organizing and invigorating Dillon’s club-like culture. There was much about his willingness to try that endeared him to me – a point of view that was not reciprocated. Whatever the reason, I was not Birkelund’s cup of tea. I will never forget one of his early addresses to the banking group. He was full of energy and launched a section of his pep talk, “When you get up in the morning and look into the mirror to shave...” He suddenly froze, looking at me (one of few or possibly the only woman in the room) with fear that his reference to a masculine practice would offend. In the hopes of putting him at ease, I said with merriment, “Don’t worry, John, girls shave too.” The whole room burst out laughing and John turned red.

Birkelund had his hands full after arriving at Dillon Read. In 1982, Nick Brady left temporarily to serve in the U.S. Senate, appointed by Governor Tom Kean of New Jersey to serve out Harrison Williams term. George Schultz left Bechtel to serve as Secretary of State under Reagan. With Brady and Schultz in Washington D.C., the Bechtel relationship stalled. With Brady returning in 1983, Birkelund engineered the repurchase of the firm from Sequoia by the partners and the creation of meaningful venture and leveraged buyout efforts. In 1986, Brady and Birkelund lead the sale of Dillon Read to Travelers, the large Connecticut insurance company that later became part of Citigroup. The relationship with Travelers expanded our capital resources to participate in the venture capital and leveraged buyout businesses. In no small part thanks to Birkelund’s hard work and dictatorial cajoling, Dillon Read would not be left behind in the 1980s boom time.

One of my favorite Dillon Read officers was the son of a former Dillon chairman and, thus, remarkably wise about the ways of the firm. I sought him out after a Birkelund temper tantrum and said that Birkelund was not at all like a “Brady Man” and that I was surprised at Nick’s choice. My colleague looked at me with surprise and said something to the effect of “Brady did not choose Birkelund. Birkelund is a 'Rothschild Man'.” I then said something about Dillon being owned by the Dillon partners, so what did the Rothschild’s have to do with us? My colleague rolled his eyes and walked away as if I was an interloper out of my league among the moneyed classes – clueless as to who and what was really in charge at Dillon Read and in the world.

After all, even Time Magazine had declared that the Rothschild invasion of America was underway.[13]

“With Dillon’s assistance Reynolds expanded out of its tobacco base into a wide variety of industries – foodstuffs, marine transportation, petroleum, packaging, liquor, and soft drinks, among others. In the process the R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. of 1963, which had revenues of $117 million, became the R. J. Reynolds Industries of 1983, a $14 billion behemoth.”

Throughout the 1980s, RJR’s huge cash flow fueled the buying and selling of companies that generated significant fees for Dillon Read’s bank accounts and investor connections for our Rolodexes.

In 1984 and 1985, Dillon Read helped RJR merge with Nabisco Brands, making the combined RJR Nabisco one of the world's largest food processors and consumer products corporations. Nabisco’s Ross Johnson emerged as the President of the combined entity. Johnson preferred the bankers he had used at Nabisco – Lehman Brothers. Johnson was on the board of Shearson Lehman Hutton.

To help RJR Nabisco digest the Nabisco acquisition, Dillon and Lehman helped to sell off eleven of RJR Nabisco’s businesses. In the process, numerous Lehman Brothers partners joined Dillon Read. Among them was Steve Fenster, who had been an advisor to the leadership of Chase Manhattan Bank and was on the board of American Management Systems (AMS), a company that figures in our story in the 1990s.

After tours of duty in Dillon’s Corporate Finance and Energy Groups, I spent four years recapitalizing the New York City subway and bus systems on the way to becoming a managing director and member of the board of directors in 1986. I did not work on the RJR account. Odd bits of news would float back. They were always about the huge cash flows generated by the tobacco business and the necessity of finding ways to reinvest the gushing profits of this financial powerhouse.

One of the young associates working for me teamed up with another young associate who worked on the RJR account to buy a sailboat in Europe. The second associate arranged to have the sailboat shipped to the U.S. through Sea-Land, an RJR subsidiary that provided container-shipping services globally. I was told RJR tore up the shipping bill as a courtesy. What kind of cash flows did a company have that could just tear up the shipping bill for an entire boat as a courtesy to a junior Dillon Read associate?

I was to get a better sense of these cash flows many years later when I read the European Union’s explanation. The European Union has a pending lawsuit against RJR Nabisco on behalf of eleven sovereign nations of Europe who in combination have the formidable array of military and intelligence resources to collect and organize the evidence for such a lawsuit. The lawsuit alleges that RJR Nabisco was engaged in multiple long-lived criminal conspiracies.

1. For more than a decade, the DEFENDANTS (hereinafter also referred to as the “RJR DEFENDANTS” or “RJR”) have directed, managed, and controlled money-laundering operations that extended within and/or directly damaged the Plaintiffs. The RJR DEFENDANTS have engaged in and facilitated organized crime by laundering the proceeds of narcotics trafficking and other crimes. As financial institutions worldwide have largely shunned the banking business of organized crime, narcotics traffickers and others, eager to conceal their crimes and use the fruits of their crimes, have turned away from traditional banks and relied upon companies, in particular the DEFENDANTS herein, to launder the proceeds of unlawful activity.

2. The DEFENDANTS knowingly sell their products to organized crime, arrange for secret payments from organized crime, and launder such proceeds in the United States or offshore venues known for bank secrecy. DEFENDANTS have laundered the illegal proceeds of members of Italian, Russian, and Colombian organized crime through financial institutions in New York City, including The Bank of New York, Citibank N.A., and Chase Manhattan Bank. DEFENDANTS have even chosen to do business in Iraq, in violation of U.S. sanctions, in transactions that financed both the Iraqi regime and terrorist groups.

3. The RJR DEFENDANTS have, at the highest corporate level, determined that it will be a part of their operating business plan to sell cigarettes to and through criminal organizations and to accept criminal proceeds in payment for cigarettes by secret and surreptitious means, which under United States law constitutes money laundering. The officers and directors of the RJR DEFENDANTS facilitated this overarching money-laundering scheme by restructuring the corporate structure of the RJR DEFENDANTS, for example, by establishing subsidiaries in locations known for bank secrecy such as Switzerland to direct and implement their money-laundering schemes and to avoid detection by U.S. and European law enforcement.

This overarching scheme to establish a corporate structure and business plan to sell cigarettes to criminals and to launder criminal proceeds was implemented through many subsidiary schemes across THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY. Examples of these subsidiary schemes are described in this Complaint and include: (a.) Laundering criminal proceeds received from the Alfred Bossert money-laundering organization; (b.) Money laundering for Italian organized crime; (c.) Money laundering for Russian organized crime through The Bank of New York; (d.) The Walt money-laundering conspiracy; (e.) Money laundering through cut outs in Ireland and Belgium; (f.) Laundering of the proceeds of narcotics sales throughout THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY by way of cigarette sales to criminals in Spain; (g.) Laundering criminal proceeds in the United Kingdom; (h.) Laundering criminal proceeds through cigarette sales via Cyprus; and (i.) Illegal cigarette sales into Iraq.[13a]

The European Union goes on to explain the role of cigarettes in laundering illicit monies:

Chapter 1

Brady, Bush, Bechtel

and "the Boys"

[1]

I remember when John Birkelund first came to Dillon Read in 1981 to serve as President

and Chief Operating Officer.[2] Dillon was a small private investment bank on Wall Street

with a proud history and a shrinking market share as technology and globalization fueled

new growth. I had joined the firm three years before and, after a period in corporate

finance, had migrated to the Energy Group – helping to arrange financing for oil and gas

companies who were clients of Birkelund’s predecessor, Bud Treman. Bud was a member

of the old school – an ethical man increasingly frustrated with the corrupting influence of

hot money and easy debt.

This was a time of transition. Dillon’s Chairman, Nicholas F. Brady, was considered one of George H. W. Bush’s most intimate friends and advisors. Both attended Yale, both were children of privilege. Bush had left his home in Greenwich Connecticut and with the help at his father’s networks at Brown Brothers Harriman had gone into oil and gas in Texas. Brady had gone to Harvard Business School and then returned to the aristocratic hunt country of New Jersey, where the Bradys and the Dillons had estates, to work at Dillon Read.

Bush climbed through Republican politics to become Director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) during the Ford Administration. After spending four years displaced by the Carter Administration, Bush was now Reagan’s Vice President with Executive Order authority for the National Security Council (NSC) and U.S. intelligence and enforcement agencies. Bush’s new authority was married with expanded powers to outsource sensitive work to private contractors. Such work could be funded through the non-transparent financial mechanisms available through the National Security Act of 1947, and the CIA Act of 1949.

This was a secret source of money for funding powerful new weaponry and surveillance technology and operations owned, operated or controlled by private corporations.[3] Carter’s massive layoffs at the CIA had created plenty of private contractor capacity looking for work.[4] An assassination attempt on President Reagan’s life two months after the inauguration meant that Vice President Bush and his team were called on to play an expanded role. Meantime, Nicholas Brady continued as an intimate friend and collaborator from his position as Chairman of Dillon Read.[5]

In April of 1981, Bechtel, working through the Bechtel private venture arm Sequoia, bought the controlling interest in Dillon Read from the Dillon family, led by C. Douglas Dillon, former U.S. Treasury Secretary[6] and son of the firm’s namesake, Clarence Dillon. This was a time when Bechtel was facing increased competition globally while experiencing a decline in the nuclear power business that they had pioneered.[7]

We found ourselves with new owners whose operations were an integral part of the military and intelligence communities and who had demonstrated a rapacious thirst for drinking from the federal money spigot.[8] George Schultz, former Secretary of the Treasury during the Nixon Administration, and now Bechtel executive, joined our board.

Unusual things started to happen that were very “un-Dillon-Ready-like.” First came a new bluntness. I will never forget the day that one of the partners brought around a very charming retired senior Steve Bechtel to tour the firm. Upon introduction, he peered up at me through thick glasses and said “Far out, a chick investment banker.” Then came strategic planning with SRI International, the think tank offshoot of Stanford University that had long standing relationships with the Bechtel family and Schultz. The head of the Energy Group that I worked for at the time was part of the planning group. His mood changed during this period and he later left the firm, retiring from the industry. Before going he warned me that I should do the same. He never said why… leaving a chill that I have felt many times since as ominous changes continue that have no name or a face.

The planning group recommended that we expand our business into merchant banking. This means managing money in venture investment by starting and growing new companies or taking controlling interests in existing companies, including “leveraged buyouts.”[9] Rather than serving companies who needed to raise money by issuing securities, or make markets in existing securities, we were going to start raising money so we could create, buy and trade companies. A company was no longer a customer. They were now a target. Wall Street was its own customer who would raise money to buy companies who would work for us. This required new people with new skills.

Chapter 2

A Rothschild Man

John Birkelund arrived at Dillon Read in September 1981. Born in Glencoe, Illinois, he

had graduated from Princeton and then had joined the Navy where he served with the

Office of Naval Intelligence in Berlin. While in Europe he became friends with Edward

Stinnes, who recruited him after a short career with Booz Allen in Chicago to work in

New York for the Rothschild family, considered to be one of if not the wealthiest family

in the world.[10] He started at Amsterdam Overseas Corporation, which then moved its

venture capital business into New Court Securities with Birkelund as co-founder. New

Court was owned by the Rothschild banks in Paris and London, Pierson Heldring Pierson

in Amsterdam and the management. Their venture successes included Cray Research,

inventor of the high-powered computers by that name, and Federal Express, the courier

company based in Memphis, Tennessee.[11]

A Time Magazine story from December 1981, “The Rothschilds Are Roving” describes a decision by the French Rothschilds in response to the nationalization of Banque Rothschild by President Mitterrand to move significant operations and focus to the U.S. Time reports that they are changing the name of their aggressive venture capital firm, New Court Securities to Rothschild, Inc. and are taking over from the current CEO, John Birkelund.[12]

Birkelund was tall and energetic. He had piercing blue eyes, a driving and hard working ambition and intelligence. He seemed frustrated by the process of organizing and invigorating Dillon’s club-like culture. There was much about his willingness to try that endeared him to me – a point of view that was not reciprocated. Whatever the reason, I was not Birkelund’s cup of tea. I will never forget one of his early addresses to the banking group. He was full of energy and launched a section of his pep talk, “When you get up in the morning and look into the mirror to shave...” He suddenly froze, looking at me (one of few or possibly the only woman in the room) with fear that his reference to a masculine practice would offend. In the hopes of putting him at ease, I said with merriment, “Don’t worry, John, girls shave too.” The whole room burst out laughing and John turned red.

Birkelund had his hands full after arriving at Dillon Read. In 1982, Nick Brady left temporarily to serve in the U.S. Senate, appointed by Governor Tom Kean of New Jersey to serve out Harrison Williams term. George Schultz left Bechtel to serve as Secretary of State under Reagan. With Brady and Schultz in Washington D.C., the Bechtel relationship stalled. With Brady returning in 1983, Birkelund engineered the repurchase of the firm from Sequoia by the partners and the creation of meaningful venture and leveraged buyout efforts. In 1986, Brady and Birkelund lead the sale of Dillon Read to Travelers, the large Connecticut insurance company that later became part of Citigroup. The relationship with Travelers expanded our capital resources to participate in the venture capital and leveraged buyout businesses. In no small part thanks to Birkelund’s hard work and dictatorial cajoling, Dillon Read would not be left behind in the 1980s boom time.

One of my favorite Dillon Read officers was the son of a former Dillon chairman and, thus, remarkably wise about the ways of the firm. I sought him out after a Birkelund temper tantrum and said that Birkelund was not at all like a “Brady Man” and that I was surprised at Nick’s choice. My colleague looked at me with surprise and said something to the effect of “Brady did not choose Birkelund. Birkelund is a 'Rothschild Man'.” I then said something about Dillon being owned by the Dillon partners, so what did the Rothschild’s have to do with us? My colleague rolled his eyes and walked away as if I was an interloper out of my league among the moneyed classes – clueless as to who and what was really in charge at Dillon Read and in the world.

After all, even Time Magazine had declared that the Rothschild invasion of America was underway.[13]

Chapter 3

RJR Nabisco

If you want to understand Dillon Read in the 1980s, you must understand R.J. Reynolds

(RJR), a tobacco company based in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. According to the

official Dillon history, The Life and Times of Dillon Read by Robert Sobel (Truman Talley

Books/Dutton, 1991) at pages 345-346, RJR had been Dillon client for many years:

“With Dillon’s assistance Reynolds expanded out of its tobacco base into a wide variety of industries – foodstuffs, marine transportation, petroleum, packaging, liquor, and soft drinks, among others. In the process the R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. of 1963, which had revenues of $117 million, became the R. J. Reynolds Industries of 1983, a $14 billion behemoth.”

Throughout the 1980s, RJR’s huge cash flow fueled the buying and selling of companies that generated significant fees for Dillon Read’s bank accounts and investor connections for our Rolodexes.

In 1984 and 1985, Dillon Read helped RJR merge with Nabisco Brands, making the combined RJR Nabisco one of the world's largest food processors and consumer products corporations. Nabisco’s Ross Johnson emerged as the President of the combined entity. Johnson preferred the bankers he had used at Nabisco – Lehman Brothers. Johnson was on the board of Shearson Lehman Hutton.

To help RJR Nabisco digest the Nabisco acquisition, Dillon and Lehman helped to sell off eleven of RJR Nabisco’s businesses. In the process, numerous Lehman Brothers partners joined Dillon Read. Among them was Steve Fenster, who had been an advisor to the leadership of Chase Manhattan Bank and was on the board of American Management Systems (AMS), a company that figures in our story in the 1990s.

After tours of duty in Dillon’s Corporate Finance and Energy Groups, I spent four years recapitalizing the New York City subway and bus systems on the way to becoming a managing director and member of the board of directors in 1986. I did not work on the RJR account. Odd bits of news would float back. They were always about the huge cash flows generated by the tobacco business and the necessity of finding ways to reinvest the gushing profits of this financial powerhouse.

One of the young associates working for me teamed up with another young associate who worked on the RJR account to buy a sailboat in Europe. The second associate arranged to have the sailboat shipped to the U.S. through Sea-Land, an RJR subsidiary that provided container-shipping services globally. I was told RJR tore up the shipping bill as a courtesy. What kind of cash flows did a company have that could just tear up the shipping bill for an entire boat as a courtesy to a junior Dillon Read associate?

I was to get a better sense of these cash flows many years later when I read the European Union’s explanation. The European Union has a pending lawsuit against RJR Nabisco on behalf of eleven sovereign nations of Europe who in combination have the formidable array of military and intelligence resources to collect and organize the evidence for such a lawsuit. The lawsuit alleges that RJR Nabisco was engaged in multiple long-lived criminal conspiracies.

Excerpt From European Lawsuit

Against

RJR Nabisco

If you like spy novels, you will find that the European Union’s presentation of fact to be

far more fascinating than fiction. One of the complaints filed in the case describes a rich

RJR history of business with Latin American drug cartels, Italian and Russian mafia, and

Saddam Hussein’s family to name a few. The Introduction reads as follows: 1. For more than a decade, the DEFENDANTS (hereinafter also referred to as the “RJR DEFENDANTS” or “RJR”) have directed, managed, and controlled money-laundering operations that extended within and/or directly damaged the Plaintiffs. The RJR DEFENDANTS have engaged in and facilitated organized crime by laundering the proceeds of narcotics trafficking and other crimes. As financial institutions worldwide have largely shunned the banking business of organized crime, narcotics traffickers and others, eager to conceal their crimes and use the fruits of their crimes, have turned away from traditional banks and relied upon companies, in particular the DEFENDANTS herein, to launder the proceeds of unlawful activity.

2. The DEFENDANTS knowingly sell their products to organized crime, arrange for secret payments from organized crime, and launder such proceeds in the United States or offshore venues known for bank secrecy. DEFENDANTS have laundered the illegal proceeds of members of Italian, Russian, and Colombian organized crime through financial institutions in New York City, including The Bank of New York, Citibank N.A., and Chase Manhattan Bank. DEFENDANTS have even chosen to do business in Iraq, in violation of U.S. sanctions, in transactions that financed both the Iraqi regime and terrorist groups.

3. The RJR DEFENDANTS have, at the highest corporate level, determined that it will be a part of their operating business plan to sell cigarettes to and through criminal organizations and to accept criminal proceeds in payment for cigarettes by secret and surreptitious means, which under United States law constitutes money laundering. The officers and directors of the RJR DEFENDANTS facilitated this overarching money-laundering scheme by restructuring the corporate structure of the RJR DEFENDANTS, for example, by establishing subsidiaries in locations known for bank secrecy such as Switzerland to direct and implement their money-laundering schemes and to avoid detection by U.S. and European law enforcement.

This overarching scheme to establish a corporate structure and business plan to sell cigarettes to criminals and to launder criminal proceeds was implemented through many subsidiary schemes across THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY. Examples of these subsidiary schemes are described in this Complaint and include: (a.) Laundering criminal proceeds received from the Alfred Bossert money-laundering organization; (b.) Money laundering for Italian organized crime; (c.) Money laundering for Russian organized crime through The Bank of New York; (d.) The Walt money-laundering conspiracy; (e.) Money laundering through cut outs in Ireland and Belgium; (f.) Laundering of the proceeds of narcotics sales throughout THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY by way of cigarette sales to criminals in Spain; (g.) Laundering criminal proceeds in the United Kingdom; (h.) Laundering criminal proceeds through cigarette sales via Cyprus; and (i.) Illegal cigarette sales into Iraq.[13a]

The European Union goes on to explain the role of cigarettes in laundering illicit monies:

V. THE LINK BETWEEN RJR’S CIGARETTE SALES, MONEY

LAUNDERING, AND ORGANIZED CRIME

Money-Laundering Links Between Europe, The United States, Russia,

and Colombia

20. Cigarette sales, money laundering, and organized crime are linked and

interact on a global basis. According to Jimmy Gurule, Undersecretary for

Treasury Enforcement: “Money laundering takes place on a global scale

and the Black Market Peso Exchange System, though based in the

Western Hemisphere, affects business around the world. U.S. law

enforcement has detected BMPE-related transactions occurring

throughout the United States, Europe, and Asia.”

21. The primary source of cocaine within THE EUROPEAN

COMMUNITY is Colombia. Large volumes of cocaine are transported

from Colombia into THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY and then sold

illegally within THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY and the MEMBER

STATES. The proceeds of these illegal sales must be laundered in order

to be useable by narcotics traffickers. Throughout the 1990s and

continuing to the present day, a primary means by which these cocaine

proceeds are laundered is through the purchase and sale of cigarettes,

including those manufactured by the RJR DEFENDANTS. Cocaine sales

in THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY are facilitated through money laundering operations in Colombia, Panama, Switzerland, and elsewhere

which utilize RJR cigarettes as the money-laundering vehicle.

22. In a similar way, the primary source of heroin within THE

EUROPEAN COMMUNITY is the Middle East and, in particular,

Afghanistan, with the majority of said heroin being sold by Russian

organized crime, Middle Eastern criminal organizations, and terrorist

groups based in the Middle East. Heroin sales in THE EUROPEAN

COMMUNITY and the MEMBER STATES are facilitated and expedited

by the purchase and sale of the DEFENDANTS’ cigarettes in money laundering operations that begin in THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY

and the MEMBER STATES, Eastern Europe, and/or Russia, but which

ultimately result in the proceeds of those money-laundering activities

being deposited into the coffers of the RJR DEFENDANTS in the

United States.

Background on the Convergence of Narcotics Trafficking and

Money Laundering

23. This complaint is about Trade and Commerce or, more correctly,

illegal Trade and illegal Commerce, and how money laundering facilitates

the financing and movement of goods internationally. Merchants

engaging in global trade often turn to the more stable global currencies

for payments of goods and services purchased abroad. In many markets,

the United States dollar is the currency of choice and, in some cases, the

United States dollar is the only accepted form of payment. Merchants

seeking dollars usually obtain them in a variety of ways, including the following three methods. Traditional merchants go to a local financial

institution that can underwrite credit. Private financing is usually available

for those with collateral. A third and least desirable source of dollar

financing can be found in the “black markets” of the world. Black

Markets are the underground or parallel financial economies that exist in

every country. Criminals and their organizations control these

underground economies, which generally operate through “money

brokers.” These “money brokers” often fulfill a variety of roles not the

least of which is an important intermediate step in the laundering process,

one that we will refer to throughout this complaint as the “cut out.”

24. The criminal activity that provides the dollars for these black market

money laundering operations is often drug trafficking and related violent

crimes. South America is the world leader in the production of cocaine,

and the United States and the European Union are the world’s largest

cocaine markets. Likewise, Colombia and countries in the Middle East

produce heroin. Cocaine and heroin are smuggled to the United States

and Europe, and are sold for United States dollars as well as in local

European currencies (and now the Euro). Russian drug smugglers obtain

heroin from the Middle East and cocaine from South America, and sell

both drugs in large quantities in the United States and in Europe. Retail

street sales of cocaine and heroin have risen dramatically over the past

two decades throughout the United States and Europe. Consequently,

drug traffickers routinely accumulate vast amounts of illegally obtained

cash in the form of United States dollars in the United States and Euros

in Europe. The U.S. Customs Service estimates that illegal drug sales in

the United States alone generate an estimated fifty-seven billion dollars in

annual revenues, most of it in cash.

25. A drug trafficker must be able to access his profits, to pay expenses

for the ongoing operation, and to share in the profits; and he must be

able to do this in a manner that seemingly legitimizes the origins of his

wealth, so as to ward off oversight and investigation that could result in

his arrest and imprisonment and the seizure of his monies. The process

of achieving these goals is the money-laundering cycle.

26. The purpose of the money-laundering cycle is to establish total

anonymity for the participants, by passing the cash drug proceeds

through the financial markets in a way that conceals or disguises the

illegal nature, source, ownership, and/or control of the money.

Background on Black

Market Money Exchanges

27. Within Europe, the United States, South America, and elsewhere, a

community of illegal currency exchange brokers, known to law enforcement officials as “money brokers,” operates outside the

established banking system and facilitates the exchange of narcotics sale

proceeds for local cash or negotiable instruments. Many of these money

brokers have developed methods to bypass the banking systems and

thereby avoid the scrutiny of regulatory authorities. These money

exchanges have different names depending on where they are located, but

they all operate in a similar fashion.

28. A typical “money-broker” system works this way: In a sale of

Colombian cocaine in THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY, the drug

cartel exports narcotics to the MEMBER STATES where they are sold

for Euros. In Colombia, the cartel contacts the money broker and

negotiates a contract, in which the money broker agrees to exchange

pesos he controls in Colombia for Euros that the cartel controls in

Europe. The money broker pays the cartel the agreed-upon sum in pesos.

The cartel contacts its cell (group) in the European Union and instructs

the cell to deliver the agreed-upon amount of Euros to the money

broker’s European agent. The money broker must now launder the Euros

he has accumulated in the European Union. He may also need to convert

the Euros into U.S. dollars because his customers may need U.S. dollars

to pay companies such as RJR for their products.

29. The money broker uses his European contacts to place the monies he

purchased from the cartel into the European banking system or into a

business willing to accept these proceeds (a process described in more

detail below). The money broker now has a pool of narcotics-derived

funds in Europe to sell to importers and others. In many instances, the

narcotics trafficker who sold the drugs in THE EUROPEAN

COMMUNITY is also the importer who purchased the cigarettes.

Importers buy these monies from the money brokers at a substantial

discount off the “official” exchange rates and use these monies to pay for

shipments of items (such as cigarettes), which the importers have ordered

from United States companies and/or their authorized European

representatives, or “cut outs.” The money broker uses his European

contacts to send the monies to whomever the importer has specified.

Often these customers utilize such monies to purchase the

DEFENDANTS’ cigarettes in bulk and, in many instances, the money

brokers have been directed to pay the RJR DEFENDANTS directly for

the cigarettes purchased. The money broker makes such payments using a

variety of methods, including his accounts in European financial

institutions. The purchased goods are shipped to their destinations. The

importer takes possession of his goods. The money broker uses the funds

derived from the importer to continue the laundering cycle.

30. In that fashion, the drug trafficker has converted his drug proceeds

(which he could not previously use because they were in Euros) to local

currency that he can use in his homeland as profit and to fund his operations; the European importer has obtained the necessary funds

from the black market money broker to purchase products that he might

not otherwise have been able to finance (due to lack of credit, collateral,

or U.S. dollars, and/or a desire for secrecy); the company selling

cigarettes to the importer has received payment on delivered product in

its currency of choice regardless of the source of the funds; and the

money broker has made a profit charging both the cartel and the

importer for his services. This cycle continues until the criminals involved

are arrested and a new cycle begins. Money laundering is a series of such

events, all connected and never stopping until at least one link in the

chain of events is broken.

31. Many narcotics traffickers who sell drugs in THE EUROPEAN

COMMUNITY now also purchase and import cigarettes. In particular, as

the trade in cigarettes becomes more profitable and carries lesser criminal

penalties compared to narcotics trafficking, the “business end” of selling

the cigarettes has become at least as attractive and important to the

criminal as the narcotics trafficking. Finally, it makes no difference

whatsoever to the money laundering system whether the goods are

imported and distributed legally or illegally.

Regardless of whether he sells his cigarettes legally or illegally, the narcotics trafficker has

achieved his goal in that he has been able to disguise the nature, location, true source,

ownership, and/or control of his narcotics proceeds. At the same time, the cigarette

manufacturer (in this case RJR) has achieved its goal because it has successfully sold its

product in a highly profitable way.[13b]

Particularly endearing, the European Union alludes to one of the most important secrets

of money laundering – that the attorney-client privilege of lawyers and law firms,

particularly the most prestigious Washington and Wall Street law firms, are a preferred

method for the communication of corporate crimes:

“RJR has been aware of organized crime’s involvement in the distribution of its

products since at least the 1970s. On January 4, 1978, the Tobacco Institute’s

Committee of Counsel met at the offices of Phillip Morris in New York City. The

Committee of Counsel was the high tribunal that set the tobacco industry’s legal,

political, and public relations strategy for more than three decades. The January 4,

1978 meeting was called to discuss, among other things, published reports concerning

organized crime’s involvement in the tobacco trade and the tobacco industry’s complicity

therein. The published reports detailed the role of organized crime in the tobacco trade

(including the Colombo crime family in New York) and the illegal trade at the

Canadian border and elsewhere. RJR’s general counsel, Max Crohn, attended and

participated in the meeting. All of the large cigarette manufacturers were present at the

meeting and represented by counsel, such as Phillip Morris (Arnold & Porter, Abe

Krash) [Author's note: Arnold & Porter is a firm that will come up several times

later in our story] and Brown & Williamson (Paul Weiss Rifkind Wharton &

Garrison, Martin London). The Committee of Counsel took no action to address,

investigate, or end the role of organized crime in the tobacco business. Instead, the

Committee agreed to formulate a joint plan of action to protect the industry from

scrutiny of the U.S. Congress.”[13c]

See a list of articles on the RJR Case and other tobacco company lawsuits in Footnotes,

this site.[13d]

You will find an update in the litigation section in the SEC annual report for 2004 for

RJR’s successor corporation, Reynolds American, as well as other updates on litigation

cases involving smuggling and slavery reparations.[14]

According to Dillon Read, the firm’s average return on equity for the years 1982-1989 was

29%. This is a strong performance, and compares to First Boston, Solomon, Shearson and

Morgan Stanley’s average returns of 26%, 15%, 18% and 31% respectively.[15] Given

what we now know from the European Union’s lawsuit and other legal actions against

RJR Nabisco and its executives, this begs the question of what Dillon’s profits would have

been if the firm had not made a small fortune reinvesting the proceeds of – if we are to

believe the European Union – cigarette sales to organized crime including the profits

generated by narcotics flowing into the communities of America through the Latin

American drug cartels.

To understand the flow of drug money into and through Wall Street and corporate stocks

like RJR Nabisco during the 1980s, it is useful to look more closely at the flow of drugs

from Latin America during the period – and the implied cash flows of narco dollars that

they suggest. Two documented situations involve Mena, Arkansas and South Central Los

Angeles, California.

Chapter 4

Narco Dollars in the

1980s — Mena, Arkansas

During the 1980s, a sometime government agent named Barry Seal led a smuggling

operation that delivered a significant amount of narcotics estimated to be as much as $5

billion from Latin America through an airport in Mena, Arkansas.[16] According to

investigative reporters and researchers knowledgeable about Mena, the operation had

protection from the highest levels of the National Security Council then under the

leadership of George H.W. Bush and staffed by Oliver North. According to investigative

reporter and author Daniel Hopsicker, when Seal was assassinated in February 1986, Vice

President George H.W. Bush’s personal phone number was found in his wallet. Through

Hopsicker's efforts, Barry Seal’s records also divulged a little known piece of smuggling

trivia – RJR executives in Central America had helped Seal smuggle contraband into the

U.S. in the 1970s.[17]

The arms and drug running operation in Mena continued after Seal's assassination. Eight

months later, Seal’s plane, the “Fat Lady,” was shot down in Nicaragua. The plane was

carrying arms for the Contras. The only survivor, Eugene Hasenfus admitted to the

illegal operation to arm the Contra forces staged out of the Mena airport. Hasenfuss’

capture inspired Oliver North and his secretary at the National Security Council to embark

on several days of shredding. The files that survived North’s shredding that were

eventually provided to Congress contain hundreds of references to drugs.

An independent counsel was appointed to investigate the concerns raised by Hasenfuss’

capture. As described in my article, "The Myth of the Rule of Law," the founders note

written by Chris Sanders, head of Sanders Research states:[18]

“The investigation resulted in no fewer than 14 individuals being indicted or convicted of

crimes. These included senior members of the National Security Council, the Secretary of

Defense, the head of covert operations of the CIA and others. After George Bush was

elected President in 1988, he pardoned six of these men. The independent counsel’s

investigation concluded that a systematic cover up had been orchestrated to protect the

President and the Vice President… During the course of the independent counsel’s

investigation, persistent rumors arose that the administration had sanctioned drug

trafficking as well as a source of operational funding. These charges were successfully

deflected with respect to the independent counsel’s investigation, but did not go away.

They were examined separately by a Congressional committee chaired by Senator John

Kerry, which established that the Contras had indeed been involved in drug trafficking and

that elements of the U.S. government had been aware of it.”

There is a standard line you hear when you try to talk to people in Washington, D.C. about

the flood of narcotics operations and money laundering in Arkansas during the 1980s.

“Oh, those allegations were entirely discredited,” they say. This is not so. Thanks to

numerous journalists and members of the enforcement community, the documentation on

Mena drug running and the related money laundering is quite serious and makes the case

that the government was engaged or complicit in significant narcotics trafficking. This

includes the various relationships to employees of the National Security Council, the

Department of Justice and the CIA under Vice President Bush’s leadership and to then

Governor of Arkansas, Bill Clinton and a state agency, the Arkansas Development and

Finance Agency (ADFA). ADFA was a local distributor of U.S. Department of Housing

and Urban Development (HUD) subsidy and finance programs and an active issuer of

municipal housing bonds. One of its law firms included Hillary Clinton and several

members of Bill Clinton’s administration as partners, including Deputy White House

Counsel Vince Foster and Associate Attorney General Webster Hubbell.

Those convicted and pardoned by President Bush included former Bechtel General

Counsel, Harvard trained lawyer Cap Weinberger who as Secretary of Defense had

presided over one of the most crime-ridden government contracting operations in U.S.

history.[19] Forbes editor James Norman left Forbes in 1995 as a result of Forbes refusal

to publish his story “Fostergate”, about the death of Vince Foster and it’s relationship to

the sophisticated software, PROMIS, allegedly used to launder money, including funds for

the arms and drugs transactions working through Arkansas. Norman’s story allegedly

implicated Weinberger in taking kickbacks through a Swiss account from Seal’s smuggling

operation. In other stories, the software was considered to be an adaptation of PROMIS

software stolen from a company named Inslaw and turned over to an Arkansas company

controlled by Jackson Stephens. An historical footnote to our story is that a later study of

the prison industry shows that Jackson Stephens’ investment bank, Stephens, Inc., was one

of the largest issuer of municipal bonds for prisons.

Some of the most compelling documentation on Seal’s Mena operation and related money

laundering was provided by William Duncan, the former Special Operations Coordinator

for the Southeast Region of the Criminal Investigation Division, Internal Revenue Service

at the U.S. Treasury. The U.S. Treasury fired Duncan in June of 1989 when he refused to

dilute or cover up the facts in Congressional testimony.[20] [21]Since it is illegal to lie to Congress, this is the equivalent of being fired for refusing to break the law, and in the

process, protecting a criminal enterprise.

The Secretary of the Treasury when Duncan was fired was Nicholas F. Brady, former

Chairman of Dillon Read. Brady left Dillon in September 1988 to join the Reagan

Administration in anticipation of Bush’s victory in the November elections. Duncan was

fired within months of two important events detailed later in the story:

(i.) the RJR Nabisco takeover made famous by the book, Barbarians at the Gate: The Fall

of RJR Nabisco by Brian Burrough and John Helyer (Harper & Row, 1990) as well as a

later movie by the same name, and

(ii.) Lou Gerstner, now chairman of the Carlyle Group, joining RJR Nabisco to make sure

that the aggressive management was in place to pay back billions of new debt issued in the

takeover.

As we will see later in our story, the inability to stop Duncan from documenting the

corruption at Mena and the U.S. Treasury, emphasized the importance of placing control

of the IRS and its rich databases and information systems which illuminated flows of

money in friendlier hands.

Narco Dollars in the 1980s

South Central, Los Angeles

Gary Webb’s "Dark Alliance" story documenting the explosion of cocaine coming from

Latin America into South Central Los Angeles during the 1980s was originally published

by the San Jose Mercury News in the summer of 1996 and then published in book form in

1998. The story and its supporting documentation were persuasive that the U.S.

government and their allies in the Contras were involved in narcotics trafficking targeted at

American children and communities.

All the usual suspects did their best to destroy Webb’s credibility and suppress his story.

This included the Washington Post, which had pulled Sally Denton and Rodger Morris’

story on Mena at the last minute in 1995 – leaving it to run later in the summer in

Penthouse Magazine. Luckily, Webb had arranged to have significant amounts of legal

documentation substantiating his story posted on the San Jose Mercury News website. By

the time that the News was pressured to take the story down, thousands of interested

people all over the world had downloaded overwhelming evidence. Thanks to the Internet,

the crack cocaine Humpty Dumpty could not be put back together again.

In response to citizen concern inspired by Webb's story, then Director of the CIA, John

Deutsch, agreed to attend a town hall meeting in South Central Los Angeles with local

Congressional representatives in November 1996. Confronted by allegations in support of

Webb's story, Deutsch promised that the CIA Inspector General would investigate the

“Dark Alliance” allegations.

This resulted in a two volume report published by the CIA in March and October of 1998

that included disclosure of one of the most important legal documents of the 1980s – a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between the Department of Justice (DOJ) and

the CIA dated February 11, 1982 in effect until August 1995.[22] At the time it was

created, William French Smith was the U.S. Attorney General and William Casey, former

Wall Street law partner and Chairman of the SEC was Director of the CIA. Casey, like

Douglas Dillon, had worked for Office of Strategic Services (OSS) founder Bill Donovan

and was a former head of the Export-Import Bank. Casey was also a friend of George

Schultz. Bechtel looked to the Export-Import Bank to provide the government guarantees

that financed billions of big construction contracts worldwide. Casey recruited Stanley

Sporkin, former head of SEC Enforcement, to serve as general counsel of the CIA. When

Schultz joined the Reagan Administration as Secretary of State, such linkages helped to

create some of the personal intimacy between money worlds and national security that

make events such as those that occurred during the Iran Contra period possible.

No history of the 1980s is complete without an understanding of the lawyers and legal

mechanisms used to legitimize drug dealing and money laundering under the protection of

National Security law. Through the MOU, the DOJ relieved the CIA of any legal

obligation to report information of drug trafficking and drug law violations with respect to

CIA agents, assets, non-staff employees and contractors.[23] Presumably, this included the

corporate contractors who, by executive order, were now allowed to handle sensitive

intelligence and national security outsourcing.

With the DOJ-CIA Memorandum of Understanding, in effect from 1982 until rescinded

in August 1995, a crack cocaine epidemic ravaged the poorer communities of America and

disenfranchised hundreds of thousands of poor people into prison who, now classified as

felons, were safely off of the voting roles. Meantime, the U.S. financial system gorged on

what had grown to an estimated $500 billion-$1 trillion a year of money laundering by the

end of the 1990s. Not surprisingly, the rich got richer as corporate power and the

concentration of investment capital skyrocketed on the rich margins of state sanctioned

criminal enterprise.

Yale Law School trained Stanley Sporkin was appointed by Reagan in 1985-86 to serve as a

judge in Federal District court, leaving the CIA with a legal license to team up with drug

dealing allies and contractors. From the bench many years later, he helped engineer the

destruction of my company Hamilton Securities while preaching to the District of

Columbia bar about good government and ethics. He retired from the bench in 2000 to

become a partner at Weil, Gotshal & Manges, Enron’s bankruptcy counsel.

Gary Webb died in 2004, another casualty of an intelligence, enforcement and media effort

that keeps global narcotics trafficking and the War on Drugs humming along by reducing

to poverty and making life miserable for those who tell the truth. At the heart of this

machinery are thousands of socially prestigious professionals like Sporkin who engineer

the system within a labyrinth of law firms, courts and government depositories and

contractors operating behind the closely guarded secrets of attorney client privilege and

National Security law and the rich cash flows of the U.S. federal credit.[24]

Chapter 5

Leveraged Buyouts

Leveraged buyouts were a phenomenon that got going in the 1980s. A leveraged buyout

(LBO) is a transaction in which a financial sponsor buys a company primarily with debt –

effectively buying the target company with the target's own cash and financial ability to

service the debt. As described in Barbarians at the Gate: The Fall of RJR Nabisco at pages

140-141:

“In 1982 an investment group headed by William Simon, a former treasury secretary, took private a Cincinnati company, Gibson Greetings, for $80 million, using only a million dollars of its own money. When Simon took Gibson public 18 months later, it sold for $290 million. Simon’s $330,000 investment was suddenly worth $66 million in cash and securities… By 1985, just two years after Gibson Greetings, there were 18 separate LBOs valued at $1 billion or more. In the five years before Ross Johnson [RJR Nabisco Chairman and CEO] decided to pursue his buyout, LBO activity totaled $181.9 billion, compared to $11 billion in the six years before that.

“A number of factors combined to fan the frenzy. The Internal Revenue Code, by making interest but not dividends deductible from taxable income, in effect subsidized the trend. That got LBOs off the ground. What made them soar were junk bonds.

“Of the money raised for any LBO, about 60 percent, the secured debt, comes in the form of loans from commercial banks. Only about 10 percent comes from the buyer itself. For years, the remaining 30 percent – the meat in the sandwich – came from a handful of major insurance companies whose commitments sometimes took months to obtain. Then, in the mid-eighties, Drexel Burnham began using high-risk “junk” bonds to replace the insurance company funds. The firm’s bond czar, Michael Milken, had proven his ability to raise enormous amounts of these securities on a moment’s notice for hostile takeovers. Pumped into buyouts, Milken’s junk bonds became a high-octane fuel that transformed the LBO industry from a Volkswagen Beetle into a monstrous drag racer belching smoke and fire.

“Thanks to junk bonds, LBO buyers, once thought too slow to compete in a takeover battle, were able to mount split-second tender offers of their own for the first time.”

In a highly leveraged company, the equity owner does not really have control. It’s the bondholder or creditor who can put the company in default. With the dirty tricks available from covert "economic hit" teams combined with a creditor's ability to throw a company in default, who needs to be a visible owner? Unmentioned was the ease and elegance with which junk bonds made it possible to take over companies with narco dollars and other forms of hot money financed by powerful partners hidden behind mountains of debt.

There emerged a growing number of attractive business savvy investment firms vying to be the owners of record for a growing number of companies taken private in leveraged buyouts. This included Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. (KKR), the LBO firm that took over RJR Nabisco in 1989 in one of the most visible takeovers of the decade, documented by Barbarians at the Gate. Dillon Read represented the RJR Nabisco board on the transaction. While the bidding war between KKR and the management group led by Ross Johnson teamed with Shearson Lehman escalated, I remember being dumbfounded as to why anyone thought that RJR Nabisco could service the proposed amounts of debt. In later years as I read reports that the debt was being serviced, I wondered what magic tricks KKR had that we mere mortals were missing. In reading Barbarians at the Gate, it turns out they managed to win despite not having the highest bid on all bidding rounds. One wonders the extent to which the bidding process was reengineered to ensure a KKR win and the media manipulated to make it look like the board had reasons to favor KKR over management other than the real reasons.

Years later, reading between the lines of the European Union lawsuit, it struck me that perhaps KKR had simply sheltered one of the worlds premier money laundering networks and, behind the veil of a private company, taken this network to a whole new level. In that same period, they recruited Lou Gerstner from American Express to run the more aggressive, more leveraged RJR. The lawsuits filed by the European Union against RJR allege that top management, including during the time Gerstner led the company as CEO, directed RJR’s illegal activities. When the European Union said “highest corporate level” and “officers and directors,” that meant Lou Gerstner – and through Gerstner and the board, the controlling shareholder, KKR.

Successful at RJR, Gerstner left to revitalize IBM and was then knighted by Queen Elizabeth. After retiring from IBM, Gerstner was chosen to chair the Carlyle Group in Washington in late 2002. The European Union’s lawsuit highlights Gerstner’s deeper qualifications to revitalize IBM, one of the most powerful military and intelligence contractors, and to lead an LBO firm like Carlyle that built its business on military and intelligence contractors and the intelligence to which such contractors are privy.[25]

Henry Kravis and George Roberts were two of the founders of KKR. Kravis’ father – successful in the Oklahoma oil and gas business – was reported to be a friend of the Bush family and had many close ties with Wall Street. Henry Kravis and his San Francisco cousin and partner, George Roberts were said to be generous supporters of the Bush campaign.

It was inconceivable to me that KKR could have won the RJR Nabisco bidding war despite lower bids without Vice President George H. W. Bush in the White House (having just won the election) and/or Nick Brady at Treasury exercising their invisible hand. Bush’s White House counsel, Harvard educated C. Boyden Gray (now partner at Wilmer Cutler) was heir to one of the many North Carolina RJR fortunes. When the bidding team led by Ross Johnson, then CEO of RJR Nabisco lost to KKR, I wondered, did Nick finally get Ross Johnson back for diluting Dillon Read’s RJR lead underwriting business after the merger with Nabisco in 1985?

When Nick Brady first got to Treasury, he was apparently slow to staff and organize his public affairs office. Before leaving Wall Street in April of 1989 to join the Bush Administration, I used to get calls from reporters looking for basic background, including his bio. One reporter asked me if I thought Brady was tough enough to survive in Washington’s treacherous waters. I responded that, “Yes, Brady did have a genteel manner. However, the world was littered with the bodies of the men and women who had underestimated Nick Brady.”

Chapter 6

A Parting of the Ways

There was an invisible spirit that crept through our lives on Wall Street in the 1980s. LBOs

were a part of it. I could never quite put my finger on what was wrong. It was as if there

was too much dirty money and, as it grew more and more powerful in invisible ways, the

way companies were financed, bought and sold grew progressively more out of control.

The common sense and humanity seemed to drain out, and as personal wealth of the

insiders grew, so did the lies.

Part of what was happening within Dillon Read was the difference in styles between Nick Brady and John Birkelund. When Nick wanted me to do something, he would come and say something like: “Look, I need you to do this and stop doing that and I can’t tell you why. I just need you to be a good soldier and do it.” And his candor had a certain charm to it and so in the spirit of being a good soldier you would give up on some deal or idea you thought was going to be a moneymaker. For some reason, Birkelund did not feel comfortable taking this straightforward approach and so situations would get caught up in complex pretzels of office politics.

For example, when the Dillon Read partners sold the firm in 1986 to Travelers, three years after buying our stock back from Bechtel, Birkelund came to my office to ask me what I thought of the deal. I told Birkelund that it was a done deal and that my opinion as one of the newest partners was irrelevant. Birkelund insisted – he really wanted to know. I told him that I was disappointed that we were no longer owners and that I thought a large insurance company would not prove to be a good business fit. He exploded with rage and stomped out of the office. Minutes later, my husband Geoffrey – a successful Wall Street attorney – called to tell me that he had just had a call from Fritz Hobbs, one of the senior Dillon partners, saying that Birkelund told him that I had resigned from the firm and that he, Geoffrey, needed to exercise some control of his wife. I explained that I had not resigned. I then advised Geoffrey to call Fritz and persuade him that he had managed to get me under control, to assure him that I had not and had no intention of resigning and that he, Geoffrey, could be counted on to make sure that I supported the sale and the changes contemplated. Hence, my partners could look to my husband to manage me. I then spent several weeks collaborating with Geoffrey on the manipulation of me – which turned out to be a remarkably effective, though unorthodox, communication vehicle.

My back channel[26] was compromised several weeks later when Ken Schmidt, the head of Dillon’s municipal department who Birkelund had also assigned to “manage” me while I managed a large and profitable client and deal flow, broke down one night after several drinks and confessed that he and my other partners were using my husband to manipulate me. Perhaps he would not have felt as guilty if he realized where Geoffrey was accessing his strategies.

After the sale of Dillon to Travelers, we put together significant Travelers financial support for our LBO business. Birkelund called me to his office to ask me if I would take the lead on marketing our LBOs to bond buyers. This request caught me off guard, as I was confident that this was a role in which I would not be successful. I asked why he thought I was appropriate. He described my success at designing and marketing $4 billion of New York City transportation systems bonds. This was a deal that nine firms had said could not be done but that had gotten done quite successfully with Dillon Read’s leadership, making the first page of the New York Times and the financial press. I explained to John that I could sell deals that I had personally structured and which I believed to be sound credits because they were based on some fundamental wealth creating purpose that would ensure the bond buyers were paid back. However, a lot of the LBOs flowing through Wall Street were not based on sound financial engineering and involved companies that were of dubious value. I was terrific with Dillon’s investment clients when I believed in a credit. Unless I was personally confident in the investments long-term viability, I was not effective at selling it.

John thought I was being difficult and I was amazed that he could not understand that just as fish don’t fly, I did not have the ability to do a good job for the firm at this task. It was as if two parallel universes were trying to communicate and failed. One was looking to go with the flow of more and more government and corporate debt without thought for how future generations would pay back all this debt – what some of us called the debt bubble – because that was the way to win at the game of hot money profits. The other thought that money served a strategic purpose and that flipping people and companies like pancakes for quick profits was risky business.

Things came to a head when I arrived at the weekly banking meeting of the Dillon Read partners one morning in 1988 and listened to Steve Fenster, one of the partners who had joined us in 1987 from Lehman Brothers with an interim stint at Chase, make his presentation on why Dillon’s LBO group should take the second position behind First Boston in the Campeau hostile takeover of the Federated Department Stores.[27] During his presentation, Fenster, later a professor at the Harvard Business School, presented a “sources and uses of funds” statement. This is a statement that estimates where the money is coming from to buy the company and how it will be spent and in what amounts. Steve described a significant source of funds would come from “productivity improvements” – a portion of what was needed to fund the cost of hundreds of millions for golden parachutes for senior management and fees for lawyers and investment bankers.

The “productivity improvements” were the increased profits to be generated by middle management over many years – all without partaking of the hundreds of millions pork fest enjoyed up front by senior management and Wall Street. We would get rich and get out up front. The guys in the trenches would work like dogs for years for scraps if the deal were to work. I was stunned. I asked Steve why in the world middle management would stick around and spend years working to generate increased profits without adequate incentives. After all, these financials would be disclosed in SEC filings. The companies’ middle managers would read the proxy and could “walk with their feet.” This meant the company would fail.

If the company failed before we sold new bonds, the Travelers bridge line that we were using would lose millions. If it failed after we sold the bonds, our customers who bought the bonds would get left holding the bag. Fenster looked at me in disgust and said something to the effect of “we will be out in December,” meaning if the deal tanks it will be someone else’s problem. I responded “Steve, our bond buyers won’t be,” meaning that Dillon would be selling the securities to pension and mutual funds and other bond buyers who would then take what could be millions in losses. By this time, Brady had left for Washington and Birkelund was now in command of the firm. Birkelund was trying to build a fortune. Nick had one to protect. It struck me that the balance that the Brady Birkelund partnership had somehow managed to strike between playing to win in the hot money game and not putting Brady’s personal reputation at risk was gone. Dillon anticipated significant fees and Fenster and the partners around the table were hungry for the quick bucks of big year-end bonuses.

That was when I decided that we might be losing sight of the line between financial engineering and financial fraud. I left the boardroom and headed downstairs to make a call to Washington, D.C. There was nothing else to learn at Dillon Read. It was time to go – I was too much a member of the old school. Other firms had indicated an interest in recruiting me. However, I had promised Nick I would institutionalize my clients and not strip the business from the firm. The way to continue to do that was to join the incoming Bush Administration in Washington, D.C. The corruption was bad, a crash was coming and Washington would lead the clean up. Besides, the corruption was being engineered in part through Washington. I wanted to understand how the economy and markets really worked. It was long my dream to find ways that investors could profit from activities that increased human and environmental safety and wealth. I needed to understand how the federal government and credit worked.

When the Federated Department Stores declared bankruptcy on January 15, 1990 as a result of their takeover by Campeau using an unsound financial structure, Dillon Read, Travelers and Dillon’s bond buyers were left holding millions of badly discounted securities. By that time, I was Assistant Secretary of Housing-FHA Commissioner at HUD managing billions of defaulted mortgages and coordinating with the group at the Resolution Trust Corporation who were managing billions of defaulted savings and loan (S&L) mortgages. While Birkelund and Fenster were explaining the Campeau-Federated defaults to Travelers, I was learning why Oliver North allegedly referred to HUD as “the candy store of covert revenues.”[28] It took years of cleaning up the mortgage mess to understand that this homebuilding and mortgage fraud was an integral part of the National Security Council’s shenanigans during Iran-Contra and a U.S. federal debt that was growing at alarming rates.

Chapter 7

“HUD is a Sewer”

As Assistant Secretary for Housing-Federal Housing Commissioner, I was responsible for

the operations of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which was the largest

mortgage insurance fund in the world. FHA at that time had annual originations of $50-

100 billion of mortgage insurance and an outstanding portfolio of $320 billion of mortgage

insurance, mortgages and properties. Leading the FHA necessitated significant

understanding of how homes are built, how mortgages finance thousands of communities

throughout America and how investors finance the process by buying securities in pools

of mortgages. My responsibilities included the production and management of assisted

private housing; management of an organization of 7,000 employees in 80 offices

nationwide; and development of network information systems and tools. In addition, I

served as advisor to the Secretary of HUD on financial markets regulatory responsibilities,

including the RTC Oversight Board, Federal Housing Finance Board and Home Loan

Bank Board System, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.