FOREWORDS

Once upon a time life was easy for the intelligence community.

Michael Joseph Savage made a mark in the sands of history with his

‘where Britain stands we stand’ declaration. It was only right that we saw

the world through British eyes and, when Britain retreated, only sensible

that we should go all the way with LBJ as an Australian Prime Minister (in

whose memory a swimming pool in Melbourne was named) once declared.

The Cold War kept us in line and on line.

In the mid-1980s we bucked the system. We may have been ahead of

our time on matters nuclear, but we were out of step with what was called

the ‘Western Alliance’. It took a break with the United States and Britain to

make the people of New Zealand aware that we were part of an international

intelligence organisation which had its roots in a different world order and

which could command compliance from us while withholding from us the

benefits of others’ intelligence.

Life at the time was full of unpleasant surprises. State-sponsored terrorism

was a crime against humanity as long as it wasn’t being practiced by the allies,

when it was studiously ignored. In the national interest it became necessary

to say ‘ouch’ and frown and bear certain reprisals of our intelligence partners.

We even went the length of building a satellite station at Waihopai. But it was

not until I read this book that I had any idea that we had been committed

to an international integrated electronic network.

It was with some apprehension that I learned that Nicky Hager was

researching the activity of our intelligence community. He has long been a

pain in the establishment’s neck. Unfortunately for the establishment, he is

engaging, thorough, unthreatening, with a dangerously ingenuous appearance, and an astonishing number of people have told him things that I, as

Prime Minister in charge of the intelligence services, was never told.

There are also many things with which I am familiar. I couldn’t tell him

which was which. Nor can I tell you. But it is an outrage that I and other

ministers were told so little, and this raises the question of to whom those

concerned saw themselves ultimately answerable.

It also raises the question as to why we persist with the old order of

things. New Zealand doesn’t have much in common with Major’s Britain

and probably less with Blair’s Britain. Are we philosophically in tune with Clinton’s USA? Is he?

Does all of that prejudice our new orientation to Asia?

There will be two responses to this book. One will be to take the easy

course of dumping on Hager. He is quite small and can easily be dumped

on. The other will be to challenge the existing assumptions and to have a

rational debate on security and intelligence. I have always enjoyed taking the

easier course but we may have been the poorer for it.

David Lange

Prime Minister

of New Zealand 1984–89

The world of signals intelligence is one that governments have traditionally tried to keep hidden from public view. The secrecy attached to it by

the United Kingdom and its allies in the Second World War, particularly

codebreaking operations, carried over into the Cold War. Whether their

adversaries were attacking them with weapons or diplomatic strategies, the

concern was the same—that revelations about methods and successes would

lead an adversary to change codes and ciphers and deny the codebreaker the

ability to read the foe’s secret communications.

Another aspect of the Second World War that carried over into the Cold

War era was the close co-operation between five countries—the United States,

the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zealand—formalised with

the UKUSA Security Agreement of 1948. Although the treaty has never been

made public, it has become clear that it provided not only for a division of

collection tasks and sharing of the product, but for common guidelines for

the classification and protection of the intelligence collected as well as for

personnel security.

But over the last 50 years, codebreaking has become far more difficult,

and often impossible—due to the use of computer-based encryption. At the

same time, the interception of unencrypted communications (for example,

air-to-ground communications) and other electronic signals—particularly radar emanations and missile telemetry—has grown dramatically in importance. This expanded role for signals intelligence was made evident in the

construction and operation of a vast network of ground stations spread across

the world, aircraft equipped with intercept antenna patrolling the skies (and

sometimes being shot down), and eventually the launch of eavesdropping

satellites. This activity did not escape the notice of the Soviet Union, which

also was busy establishing its own elaborate network. It also became very

evident to outsider observers that signals intelligence was an important and

very expensive part of the Cold War.

That signals intelligence became more noticeable did not, for many years,

alter the attitudes of the authorities about the necessity for strict secrecy. In

the United States the National Security Agency, established in 1952, was

officially acknowledged only in 1957. For years, what were well known to

be US operated signals intelligence stations have been officially described as

facilities engaged in the research of ‘electronic phenomena’ or the ‘rapid-relay

of communications.’ It took the US over 20 years after the Soviet Union

obtained detailed information on a US signals intelligence satellite even to

acknowledge the existence of such satellites. Other nations have been equally

reticent—the very existence of Canada’s Communications Security Establishment was first revealed by the media in 1975.

In recent years some of the UKUSA governments have been somewhat more forthcoming about signals intelligence sometimes with regard

to historical events, sometimes with respect to organisational structure, and

sometimes about some aspects of current operations. But secrecy is still

intense (although no more than in other countries). What the public does

know, it knows largely because of the efforts of industrious researchers who

have collected and analysed obscure documents and media accounts, and

interviewed present and former intelligence officers who can shed light on

signals intelligence operations. These researchers have included Desmond

Ball in Australia, James Bamford in the United States and Duncan Campbell

in the United Kingdom.

Nicky Hager’s Secret Power earns him a place in that select company. Indeed, he has produced the most detailed and up-to-date account in existence

of the work of any signals intelligence agency. His exposé of the organisation

and operations of New Zealand’s Government Communications Security

Bureau (GCSB) is a masterpiece of investigative reporting and provides a

wealth of information.

The reader of Mr Hager’s book will learn about not just New Zealand’s

signals intelligence activities, but those of its partners. Specifically, the reader will learn about the origins, the evolution, and internal structure of the GCSB;

the Tangimoana and Waihopai ground stations and their operations; New

Zealand’s role in the UKUSA alliance, and some of the signals intelligence

operations of the other UKUSA nations. Secret Power also serves as a fascinating case study of the role of a junior partner in an intelligence alliance.

Some, undoubtedly, will object to the unprecedented detail to be found

in the book, taking the traditional view that secrecy is far more important

than public understanding of how tax dollars are being spent on intelligence. Certainly, revelations that defeat the purpose of legitimate intelligence

activities are unfortunate and waste those tax dollars. But the UKUSA governments and their intelligence services have been far too slow in declassifying

information that no longer needs to be secret and far too willing to classify

information that need not be restricted. A Canadian newspaper made the

point rather dramatically a few years ago—after being denied access to a

Canadian signals intelligence facility, the paper promptly purchased on the

open market, and published, a satellite photograph of the facility, and its

antenna system, first obtained by a Soviet spy satellite.

There are many individuals within the services who would prefer greater

openness, but they frequently cannot overcome the intense opposition of

those preaching the need for tight secrecy. The internal bureaucratic battle to

get information declassified can be a long and intense one and those opposing disclosure have an advantage—often they are those in charge of security,

who have developed a mindset which views any revelation as damaging. In

the meantime, the public is kept in the dark. A free press, as manifested in

books such as Mr Hager’s, is a large step towards alleviating the problem.

Jeffrey T. Richelson

Alexandria, Virginia

May, 1996

Jeffrey Richelson is a leading authority on United States intelligence agencies and author

of America’s Secret Eyes in the Sky, and co-author of The Ties That Bind.

INTRODUCTION

The Government Communications Security Bureau (GCSB) is the most

secret organisation in New Zealand. It is also by far the country’s largest and

most significant intelligence organisation, yet not one in 100 New Zealanders would even know its name. This book, which focuses on the GCSB but

covers other New Zealand agencies involved in foreign intelligence work,

aims to change that. Every chapter contains important information that has

never before been published. Readers deserve some explanation of how the

information has come to be published—and of why I believe that they should

be not just curious or intrigued, but actively concerned about the activities

of intelligence organisations.

I began research on the GCSB almost accidentally in mid-1984 when I

went with friends to visit the recently discovered Tangimoana signals intelligence station, north of Wellington. (Signals intelligence, the work of the

GCSB, involves spying electronically on others’ communications. With so

much human activity revolving around the use of telephone, telex, fax and

e-mail, it is the most important type of spying in the world today.) When no

one appeared from the buildings to tell us to go away, we wandered around

noting down everything we could see: from the shapes of the aerials that

surrounded us to the number plates of the cars in the station car park.

Much later, a trip to the Post Office provided the names of the cars’

owners, and suddenly a window into the inner workings of the GCSB was

thrown open. I had some spare time between projects so I went to a library

and looked up the names in the index of the voluminous annual public

service staff lists. There they were, listed in an obscure Ministry of Defence occupational class, together with 80 of their colleagues who had also

been hidden there. By looking at the lists from earlier years I could see the

growth of New Zealand radio interception activities over 30 years, including

where they had been based before Tangimoana and their regular postings to Singapore, Australia and elsewhere.

Two years passed before I had time to investigate further. Then it occurred to me that the rest of the GCSB staff were probably also hidden within

the Defence lists. Although they were scattered anonymously through pages

of ordinary Defence personnel, there was a ridiculously simple way to sort

the military from the spies. Using the Ministry of Defence internal phone

directory, I crossed out all the names of true Defence staff—leaving me with

a virtually full list of the staff and their positions in the secret organisation.

It was these staff lists that allowed me to begin to understand what went

on inside the GCSB. None of the sources for the lists was secret and since then

I have pieced together information from a great many other sources. As with

all research, each step forward suggested new ones. Much of the information

in the book was obtained from interviews with more than 50 people who

are or have been involved in intelligence and related fields in New Zealand

and elsewhere. Because of the nature of their jobs, these interviews had to

proceed on the condition that the people involved would not be identified.

Some of the information arrived in unexpected ways. Other snippets turned

up simply because New Zealand is a small place.

Other sources of information have included the Official Information Act,

the National Archives, job advertisements, overseas researchers and publications and a lot of fieldwork. It has of course not been easy to research such

closed organisations. Often days or weeks of work have gone into compiling

the facts for one or two pages of final text. Rigid secrecy within intelligence

agencies has meant that, even where inside sources were used, many ‘insiders’ could only contribute fragments of the story, and even the most

informed sources still knew no more than 5–10% of the subjects covered. The

straightforward way I have recorded the information belies the difficulties

of gathering it.

The New Zealand intelligence organisations are so thoroughly a part of

the United States system that I have been able to uncover new information

about the workings of the entire international system. Chapters 2 and 3, for

instance, contain the first description ever published of the American–British–

Canadian–Australian–New Zealand system that targets most of the civilian

communications in the world, including where the interception occurs, how

it is done, its capabilities, how the staff operate the system and even the secret

codenames. This information has significance for many countries far from

New Zealand.

If this book contained only information that the intelligence authorities were prepared to make public, it would be very short and much of its

content would be misleading. There are, however, various pieces of sensitive

information about the GCSB that I have not included. For example, revealing

some intelligence targets (both of New Zealand and allied agencies) would

have damaged interests that most readers would agree are worth protecting,

without adding substantially to an understanding of the organisation. But

naming some of the targets in general terms will be no great surprise to the

targets themselves. In the case of some other small and vulnerable nations, if

they have not suspected that they are being intercepted, they should know.

Also, I have named senior staff, at the levels where such people in all

government organisations can expect publicity, but have mentioned other staff

only where it adds to an understanding of the organisations concerned. Detailed references to an individual do not mean that I obtained the information

concerned from that individual. I have not spoken to or received information

from any of the intelligence staff specifically described in this book.

In some places detailed information has been included primarily so that it

will be harder for the intelligence authorities to claim that the main content

of the book is unfounded. In other places a lot of detailed information has

been left out, either because it is not relevant to the book’s central themes

or so that individuals who provided information cannot be identified.

I have thought hard about the new information published in this book

and I am confident that it will help, not harm, the real defence and security

of New Zealand. I say this because the predictable response of secretive

institutions when they are exposed is to claim (as they will) that the security

of the country has been imperilled. I believe it is vital to uncover important

information that is being withheld from governments and the public and to

prompt some very necessary change.

There is a difference between defence and security and individual opinions about defence and security. Publishing this book will not fit with some

officials’ political opinions about what is best for the defence and security of

New Zealand, but that is quite a different matter from what actually matters

for the protection and security of New Zealanders.

I would appreciate being contacted by readers who have information

that adds to the information in the book or who have information on other

subjects that should be made public.

All writers write from a particular perspective. I believe that spying and

other intelligence activities are not, in themselves, necessarily good or bad.

Issues of right and wrong arise in relation to who is being spied upon, who is given access to the intelligence and what they do with it. Few New Zealanders would object, for example, to intelligence activities aimed at protecting

New Zealand from attacks such as the 1985 Rainbow Warrior bombing. But

I am appalled that New Zealand provides very detailed intelligence about its

small and vulnerable South Pacific neighbours to outside powers which are

aggressively pursuing their own interests in the region.

Intelligence is not just neutral information; it can be powerful and dangerous. Intelligence gathering and military force are two sides of the same

coin. Both are used by countries and groups within countries to advance their

interests, often at the expense of others. To influence or defeat an opponent,

knowledge can be more useful than military force.

The type of intelligence described in this book, signals intelligence, is the

largest, most secret and most expensive source of secret intelligence in the

world today. This eavesdropping on the communications of other countries

has implications for power relations between countries in every part of the

globe.

Too often, the signals intelligence alliance has involved New Zealand in

international military and political issues and disputes which, if they knew

about them, many New Zealanders would not support. The middle chapters

of the book document New Zealand involvement in electronic spying operations against countries and territories including Russia, China, Vietnam,

France, Japan, Argentina, Bougainville, East Timor, Vanuatu and all the other

South Pacific states, usually directly on behalf of one of the intelligence allies.

Some of these operations just appear pointless for New Zealand, others are

for very dubious purposes.

These are also the chapters that describe how the spying is done, who

does it and the common security regulations and technical systems which

bind the alliance together. As you read it will become clear that virtually

everything—the equipment, manuals, ways of operating, jargon, codes and

so on—has been imported in entirety from the overseas allies to be used in

New Zealand as part of the international system.

Although, superficially, the intelligence alliance provides New Zealand

with a great deal of information, it appears that very little of it is important.

Chapter 12 has precise details of the intelligence New Zealand receives from

its four closest allies; then the final chapter quotes a range of senior officials

and politicians who argue that this intelligence has served little or no useful

purpose for New Zealand. The publicly claimed benefits of intelligence cooperation, such as that New Zealand receives vital economic intelligence and information on terrorism, do not stand up to close examination. Examples

such as the Rainbow Warrior bombing show that agencies set up to serve

alliance priorities repeatedly fail when they are needed close to home.

I have found no significant evidence of the intelligence alliance defending New Zealanders or of the intelligence it produces having an important

influence on policy decisions. The implications of being a junior member of

the alliance—which means New Zealand interests coming second to those

of the larger allies—have probably had far more significance for government

policy than has the actual intelligence collected and exchanged.

But there is ample evidence that the intelligence alliance has contributed to the destruction rained upon innocent people in wars since 1945,

and that most often it has been assisting powerful interests at the expense

of the vulnerable. In any account of the activities of the powerful it is hard

to keep sight of what it all means for the ordinary people who, somewhere

far below, suffer as a result. I believe the challenge for the thoughtful is to

try keep these human results in mind. When nations compete, whether it be

politically, militarily or economically, it is not the Josef Stalin's, George Bush's

or Saddam Hussein's who are hurt or killed.

No criticism is intended of the majority of people who work for the

intelligence organisations described in this book. Most of them sincerely

believe they are acting in the best interests of their country; they are ordinary

people who just happened to end up with a job in intelligence. Many have

(or, if they knew what was going on, would have) the same concerns about

the organisations as other citizens. Good people can work in organisations

that do great harm.

Some senior officials, however, do deserve criticism, for an arrogance that

leads them to believe they know better than the politicians and public they

are supposed to serve. When this involves them in secretly pursuing policies

contrary to what the public would support and without even the permission

of the government, change is obviously overdue.

Numerous examples are given of officials withholding information from

governments and the public—and, at times, actively deceiving them. The

book shows, for example, that in the 1985–90 period, when the public and

government were led to believe New Zealand was moving to greater independence in intelligence matters, a process of rapid integration into the

alliance was actually occurring. Similarly, the much debated 1985 ‘cut’ of

United States intelligence to New Zealand did not occur. The government

and the public were hearing only what it suited the officials to tell them.

Inadequate New Zealand control over the GCSB, the reasons for which are described in Chapter 13, means that the alliance partners have considerably more influence over New Zealand intelligence priorities and operations

than do New Zealand governments. Chapter 13 also explains why new

intelligence oversight legislation passed in 1996 did little to improve this

situation—it actually shut the door on Parliament being able to find out for

itself what New Zealand’s spies are up to.

Researching and writing about intelligence activities has been a continuation of my work in helping to secure New Zealand’s nuclear-free status.

The vision behind the nuclear-free policy is that international politics must

change and that small countries have a role in helping to lead the way. This

applies equally to New Zealand’s membership of the intelligence alliance,

which stands in the way of New Zealand playing a positive role in world

affairs.

That role should be one of reducing international conflict, confronting injustice and protecting the environment. By leaving the alliance, New

Zealand would have more integrity in its international relations and could,

over time, set a much needed example for other nations. That is what the

nuclear-free policy has done, but for the last decade the intelligence alliance

has maintained its counter-influence over New Zealand politics because, to

date, it has been impregnably secret.

New Zealand’s intelligence ties also, I believe, work against participatory

democracy, by encouraging a culture of secrecy and by replacing democratic

processes with channels for foreign influence. The effect has been to increase

the power of a highly paid group of government officials, reduce the influence of the government and Parliament and often entirely exclude the public

from important issues.

During the time I have been involved with the nuclear-free issue I have

often found myself pushing against this invisible current, a current which

time and again leads governments to follow the wishes of the foreign allies

against the majority wishes of the New Zealand public. This, alone, is enough

justification for leaving the intelligence alliance. New Zealand policy cannot

help being affected by the fact that the main intelligence allies have a ‘big

power’ view of the world, quite different from that of most New Zealanders,

and often favour violent solutions to international disputes. Two of them

continue to be nuclear armed.

The research for this book was undertaken with the knowledge of the

GCSB, who were offered an opportunity to discuss it with me. I wrote to the

director, Ray Parker, three times offering to visit him to discuss my research.

The first two times he did not even acknowledge the offer. The third time,

when I asked why he was not replying, he replied tersely: ‘I acknowledge your offer to visit the Bureau for the purpose of explaining the purpose of

your research. I do not wish to avail myself of your offer.’

Over the last 10 years a lot has been heard in New Zealand about the

dangers of ‘bureaucratic capture’, about senior officials controlling their

ministers rather than the other way around. The area of government activity

described in this book is the ultimate example of bureaucratic capture. Politicians, whom the public has presumed will be monitoring the intelligence

organisations on their behalf, have been systematically denied the information

required to do that job.

If a democratic society wants to control its secret agencies, it is essential

that the public and politicians have the information and the will to do so.

Providing information on these most secret state activities is the purpose of

this book. Anyone who reads it will know a lot more about New Zealand

intelligence activities and the international system of which they are part than

all the members of Parliament, the Cabinet ministers and even the prime

ministers who have supposedly been in charge. Then it is up to those readers

to take this information and force long overdue restructuring and change.

1

1984

It was a grumpy Rob Muldoon who walked across from the Beehive building to the parliamentary chamber on Tuesday, 12 June 1984. After nine

years as an increasingly embattled prime minister, his rule was disintegrating.

That morning the Leader of the Opposition, David Lange, had announced

his party’s foreign policy: New Zealand would be made unconditionally

nuclear free and the ANZUS Treaty would have to be renegotiated. Later

that day two National Party MPs crossed the floor in Parliament to vote for

a Labour Party-sponsored Nuclear Free New Zealand Bill, almost defeating the government. Two days later, blaming these anti-nuclear defectors, a

visibly intoxicated Muldoon threw in the towel and called an early general

election.

That Tuesday afternoon Muldoon was on his way to the 2.30 pm session

of Parliament to read a prepared ministerial statement about a quite different

subject: an obscure agency called the Government Communications Security

Bureau (GCSB). The GCSB had been set up secretly under Muldoon seven

years earlier and had been quietly growing in size throughout his reign.

Until just two months before Muldoon’s statement the public had never

even heard of the GCSB. Then peace researcher Owen Wilkes publicised the

existence of a secret radio eavesdropping station run by the GCSB at Tangimoana Beach, 150 kilometres north of Wellington, revealing for the first

time that New Zealand was involved in this type of intelligence collection. Muldoon was delivering the government’s reply to the publicity.

The brief statement he read was, and remains, the most information

the government has ever been prepared to release about the GCSB and the

Tangimoana station. It acknowledged that the GCSB was involved in signals

intelligence—intercepting the communications of governments, organisations

and individuals in other countries—and said New Zealand had collected that

type of intelligence since the Second World War. It noted that the GCSB

liaised closely with Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom and the United

States—the closest the government has ever come to talking about the secret

five-nation signals intelligence alliance of which the GCSB is part. But much

of the statement was designed to mislead.

It said that the Tangimoana station did not monitor ‘New Zealand’s

friends in the South Pacific’. The big aerials at the station were right then

monitoring nuclear-free Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands, Fiji and all New

Zealand’s other South Pacific neighbours—everyone in the South Pacific,

in fact, except for the Western intelligence allies and their territories. Large

quantities of telexes and Morse code messages sent by long-distance radio

in the Pacific region were being recorded at Tangimoana and sent to the

GCSB in Wellington for distribution to select public servants and to the four

intelligence allies.

The statement also said that Tangimoana ‘does not come under the direction of any Government, or external agency, other than the New Zealand

Government’. In fact, the communications officers in a secure room within

the station were regularly receiving directions from the overseas allies and

sending them back intelligence collected on their behalf.

As soon as Muldoon sat down, the Leader of the Opposition stood up

to respond. Lange, who five weeks later would be Prime Minister, thanked

Muldoon for removing the cause of suspicion which had surrounded the

Tangimoana facility: ‘In particular, I am grateful that he has given an absolutely unqualified assurance, which I believe to be of paramount importance,

that the facility is under the full control of the New Zealand Government’.

On that same Tuesday one of the GCSB’s newest employees left for work from

his home in Khandallah, overlooking Wellington Harbour. He had recently

moved into a key position overseeing the GCSB’s policy and planning. After

the GCSB director, this would be the most influential position in determining

the GCSB’s direction through its most important period of growth.

Glen Singleton had already made an impression on his colleagues. He

was always polite and sociable, but kept his opinions to himself. Privately, he told work friends that he did not much

like the top people at the GCSB. The

other directors at the GCSB, mostly

ex-Air Force, had little in common

with his tastes for antiques, paintings

and good food.

Arriving at work, Singleton took

the lift to the 14th floor of the Freyberg Building headquarters. He held

his magnetic security pass up to the

right spot on the heavy wooden doors

and an unseen black box registered

that he had arrived and automatically

opened the door.

In 1984 this top floor contained

the GCSB’s communications centre,

its 24-hour link to its overseas allies,

the linguists who translated intercepted messages and some of the deputy

directors. Singleton’s office had been

positioned next to the director’s, with

wide views across the harbour. Staff

recall that ‘he wandered in and out

of the director’s office whenever he

wanted’ and that he ‘had the director’s ear’

One of the many things Lange did not know about the GCSB when he

spoke in Parliament that afternoon, and would never know, even as Prime

Minister, was that this new officer was not under the control of the New

Zealand government at all. Paid in American dollars and living in a house

rented for him by the local United States embassy, Singleton was an employee

of an organisation called the National Security Agency (NSA).

The NSA is the United States’ largest, most secret and probably most

expensive intelligence organisation. It rings the world with intelligence stations, ships, submarines, aircraft and satellites that act as the ‘platforms’ for

its global electronic spying operations. It has immense intelligence collecting

capabilities. As a remarkable exposé, The Puzzle Palace by James Bamford,

shows, the NSA is the big brother of all such intelligence organisations in the

Western world. Its intelligence links with four especially close allies—Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand—are formalised in a highly secret agreement called UKUSA (pronounced ‘you-koo-za’).

Glen Singleton, still in his early 30s, was on a three-year posting to the

GCSB. He had grown up and been educated in the city of Cleveland in Ohio.

After university study in international relations, he moved to Washington

DC to work for the NSA. In late 1984, after settling in as a foreign officer

inside the GCSB, he was formally appointed as the GCSB’s Deputy Director

of Policy and Plans. In this role he advised the GCSB director regularly, directed the work of other GCSB staff and showed overseas visitors around the

GCSB. He visited the United States embassy often, travelled to the Defence

Signals Directorate (DSD) in Melbourne for meetings and received special

private communications from his Washington bosses. Between 1984 and

1987 he would help to make the plans for a period of dramatic expansion of

the GCSB’s operations and capabilities. Later he would return to the GCSB,

having left the NSA, and move into another key role.

Having an American inside the GCSB serving as a foreign liaison officer

would be one thing; allowing an officer from another country to direct policy

and planning seems extraordinary.

During his first three years on the NSA posting Singleton hosted 50 or

more staff from the Wellington intelligence organisations to 4 July parties

at his home. But outside intelligence circles, not even the Prime Minister

knew of his role. As another former Prime Minister said about the GCSB:

‘You don’t know what you don’t know. The whole thing was a bit of an act

of faith.’

Nineteen eighty-four was a special year for the GCSB. The directors of the

five UKUSA agencies meet together once a year to plan and co-ordinate the

activities of the global intelligence alliance. The agencies take turns to host

the meeting; this year it was the GCSB.1

Throughout the early 1980s the GCSB had been expanding: more than

doubling its staff, opening the Tangimoana station and, most pleasing to

the director, establishing various new intelligence analysis sections that had

given the GCSB more to offer within the alliance.

Five years before, the organisation had been squeezed into a corner of

Defence headquarters. Now the flags of the five nations were out on display

to greet the UKUSA agency heads to the spacious new Freyberg Building

headquarters. After a special welcome for the overseas directors, they met

in the 14th floor conference room attached to the director’s office, looking

out over the pine-clad Wellington hills and, in the foreground, the Stars and Stripes fluttering outside the nearby American embassy.

The most important visitor was Lieutenant-General Lincoln D. Faurer,

head of the NSA. With him were Peter Marychurch, head of the British

Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), Peter Hunt, head

of the Canadian Communications Security Establishment (CSE), and Tim

James, head of the Australian DSD.

Although what was discussed at this meeting is not known, the issues

facing the intelligence alliance were clear. The agenda would have included

plans for new computer and communications systems, which would help to

integrate GCSB operations into the NSA-controlled network, and in particular preparations for a new, super-secret global intelligence system of which

New Zealand would be an integral part. It would have been made clear that,

as part of the new global system, the NSA required new signals intelligence

stations in the South Pacific by the end of the decade to intercept satellite

communications. Over the next three years, it would be the job of the GCSB

Director, Colin Hanson, and his Australian counterpart to manoeuvre their

governments towards approving such a project.

The meeting may also have discussed the nuclear-free issue, which was

simmering away as Lange’s new Labour government settled into office.

Only a few months later, on 27 February 1985, Lange met a United States

State Department official, William Brown, across the dining table of the

New Zealand consul general’s residence in Los Angeles. It was a short and

tense meeting.

The nuclear-free issue had come to head in New Zealand. Deciding to

follow public opinion rather than the advice of its officials, the Labour government had refused entry to the American nuclear-capable warship, USS

Buchanan, and now Lange was being read the list of retaliatory measures

that would be imposed by the United States government. These included

cutting many of the military ties between the two countries; in effect the

ANZUS Treaty died that day. And, as part of the reprisals, according to the

then Chief of Defence Staff, Sir Ewan Jamieson, ‘the flow of information

[from the United States], on which the New Zealand intelligence community

was heavily dependent, was terminated’.2

All the journalists, commentators and ‘well placed sources’ were repeating the same message. As far as the public knew, all intelligence ties between

New Zealand and the United States were severed.

This was completely untrue. While intelligence from military sources

was cut considerably, most of the intelligence flow from the United States continued uninterrupted. The

United States government wanted

other countries to see New Zealand

punished for its nuclear-free policies, but the UKUSA alliance was

too valuable to be interrupted by

politics.

A few days before Lange’s

meeting in Los Angeles, the GCSB

received a call from its liaison officer at the NSA’s headquarters in

Washington DC. Warren Tucker,

who had moved into the position

a few weeks before and would later become Director of Operations

back at the GCSB, told the senior GCSB staff that the announcement was

coming but reassured them that his position at the NSA was secure. While

other New Zealand diplomatic staff in Washington were frozen out by their

United States government contacts, Tucker was envied because his position

was largely unaffected.

The communications centre (the ‘commcen’) back in the GCSB’s Wellington headquarters was the first place where practical signs of the Los

Angeles reprisals were noticed. Here mostly ex-Navy communications staff

worked around the clock maintaining contact with the four sister agencies.

Every day, hundreds and hundreds of intelligence reports were spat out

of the large sound-proofed printers, more reports than the small Wellington

intelligence agencies even had time to read. In February 1985, the GCSB

was receiving reports about the minute details of the Iran–Iraq War, Soviets

in Afghanistan, a weekly list of all the Libyan students in Britain and a lot of

other marginally interesting top secret reports. But there was nothing, among

the screeds of reports on international terrorism, about the French DGSE

agents who were right then on their way to New Zealand to become the

first foreign terrorists in New Zealand’s history: blowing up the Greenpeace

ship Rainbow Warrior.

Most of the daily flood of overseas reports did not stop. But the communications staff noticed that the ‘routing indicators’, which show the origin

and destination of documents within the UKUSA system, had been removed

from incoming reports. While the public condemnation of New Zealand’s

nuclear-free policy by the United States government increased in pitch, it

February 1985 news of severed intelligence links

was simply untrue.

25

seems some strategist in Washington decided there should be no tangible

evidence that United States intelligence reports were still arriving in Wellington. They did not want to take the risk that one of these documents

might one day be held up in public as evidence that the New Zealand had

got away with its nuclear-free policy.

Later, when the public debate had cooled, the usual routing indicators

quietly reappeared on the overseas reports. While governments, journalists

and the public around the world were led to believe that United States-New

Zealand intelligence ties had been cut, inside the five-agency network it was

mostly business as usual.

The United States military was unsentimental about its decades of alliance

links with the New Zealand armed forces; military exercises, exchanges and

other visible links were completely cut. But New Zealand’s involvement in

the UKUSA intelligence alliance, first alluded to in public by Muldoon only

nine months before, was too useful to the overseas allies to be interrupted

by a quarrel over nuclear ships.

The 20 Intelsat (International Telecommunications Satellite Organisation) satellites that ring the world above the Equator carry most of the world’s satellite-relayed international phone calls and messages such as faxes, e-mail and telexes. The new satellite, Intelsat 701, replaced the 10-year-old Intelsat 510 in the same position. The changeover occurred at 10 pm New Zealand time that summer evening.

There have been various guesses and hints over the years about what the Waihopai station was set up to monitor—‘sources’ in one newspaper said foreign warship movements; a ‘senior Telecom executive’ told another newspaper it was most likely ‘other countries’ military communications’— but, outside a small group of intelligence staff, no one could do more than theorise. Waihopai was established specifically to target the international satellite traffic carried by Intelsat satellites in the Pacific region and its target in the mid-1990s is the Intelsat 701 that came into service in January 1994, and is the primary satellite for the Pacific region.

Intelsat satellites carry most of the satellite traffic of interest to intelligence organisations in the South Pacific: diplomatic communications between embassies and their home capitals, all manner of government and military communications, a wide range of business communications, communications of international organisations and political organisations and the personal communications of people living throughout the Pacific. The Intelsat 7 satellites can carry an immense number of communications simultaneously. Where the previous Intelsat 5s could carry 12,000 individual phone or fax circuits at once, the Intelsat 7s can carry 90,000. All ‘written’ messages are currently exploited by the GCSB. The other UKUSA agencies monitor phone calls as well.

The key to interception of satellite communications is powerful computers that search through these masses of messages for ones of interest. The intercept stations take in millions of messages intended for the legitimate earth stations served by the satellite and then use computers to search for pre-programmed addresses and keywords. In this way they select out manageable numbers (hundreds or thousands) of messages to be searched through and read by intelligence analysis staff.

Until the Intelsat 701 satellite replaced the older 5 series, all the communications intercepted at Waihopai could already be got from two existing UKUSA stations covering the Pacific. But, unlike their predecessors, this new generation of Intelsat 7s had more precise beams transmitting communications down to the southern hemisphere. The existing northern hemisphere-based stations were no longer able to pick up all the southern communications, which is why new stations were required.

Eleven months later, on 3 December 1994, the other old Intelsat satellite above the Pacific was replaced by Intelsat 703. Since then Waihopai and its sister station in Australia constructed at the same time have been the main source of southern hemisphere Pacific satellite communications for the UKUSA network.

Many people are vaguely aware that a lot of spying occurs, maybe even on them, but how do we judge if it is ubiquitous or not a worry at all? Is someone listening every time we pick up the telephone? Are all our Internet or fax messages being pored over continuously by shadowy figures somewhere in a windowless building? There is almost never any solid information with which to judge what is realistic concern and what is silly paranoia.

What follows explains as precisely as possible—and for the first time in public—how the worldwide system works, just how immense and powerful it is, and what it can and cannot do. The electronic spies are not ubiquitous, but the paranoia is not unfounded.

The global system has a highly secret codename—ECHELON. It is by far the most significant system of which the GCSB is a part, and many of the GCSB’s daily operations are based around it. The intelligence agencies will be shocked to see it named and described for the first time in print. Each station in the ECHELON network has computers that automatically search through the millions of intercepted messages for ones containing pre-programmed keywords or fax, telex and e-mail addresses. For the frequencies and channels selected at a station, every word of every message is automatically searched (they do not need your specific telephone number or Internet address on the list).

All the different computers in the network are known, within the UKUSA agencies, as the ECHELON Dictionaries. Computers that can search for keywords have existed since at least the 1970s, but the ECHELON system has been designed to interconnect all these computers and allow the stations to function as components of an integrated whole. Before this, the UKUSA allies did intelligence collection operations for each other, but each agency usually processed and analysed the intercept from its own stations. Mostly, finished reports rather than raw intercept were exchanged.

Under the ECHELON system, a particular station’s Dictionary computer contains not only its parent agency’s chosen keywords, but also a list for each of the other four agencies. For example, the Waihopai computer has separate search lists for the NSA, GCHQ, DSD and CSE in addition to its own. So each station collects all the telephone calls, faxes, telexes, Internet messages and other electronic communications that its computers have been pre-programmed to select for all the allies and automatically sends this intelligence to them. This means that the New Zealand stations are used by the overseas agencies for their automatic collecting—while New Zealand does not even know what is being intercepted from the New Zealand sites for the allies. In return, New Zealand gets tightly controlled access to a few parts of the system.

When analysts at the agency headquarters in Washington, Ottawa, Cheltenham and Canberra look through the mass of intercepted satellite communications produced by this system, it is only in the technical data recorded at the top of each intercept that they can see whether it was intercepted at Waihopai or at one of the other stations in the network. Likewise, GCSB staff talk of the other agencies’ stations merely as the various ‘satellite links’ into the integrated system. The GCSB computers, the stations, the headquarters operations and, indeed, the GCSB itself function almost entirely as components of this integrated system.

In addition to satellite communications, the ECHELON system covers a range of other interception activities, described later. All these operations involve collection of communications intelligence, 1 as opposed to other types of signals intelligence such as electronic intelligence, which is about the technical characteristics of other countries’ radar and weapon systems.

Throughout the 1970s only two stations were required to monitor all the Intelsat communications in the world: a GCHQ station in the southwest of England had two dishes, one each for the Atlantic and Indian Ocean Intelsats, and an NSA station in the western United States had a single dish covering the Pacific Intelsat.

The English station is at Morwenstow, at the edge of high cliffs above the sea at Sharpnose Point in Cornwall. Opened in 1972–73, shortly after the introduction of new Intelsat 4 satellites, the Morwenstow station was a joint British-American venture, set up using United States-supplied computers and communications equipment, and was located only 110 kilometres from the legitimate British Telecom satellite station at Goonhilly to the south. In the 1970s the Goonhilly dishes were inclined identically towards the same Atlantic and Indian Ocean satellites.2

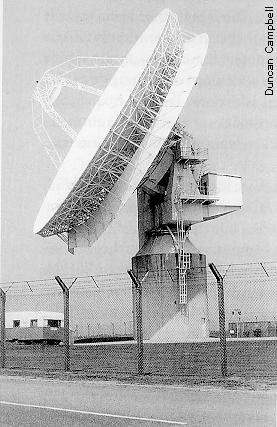

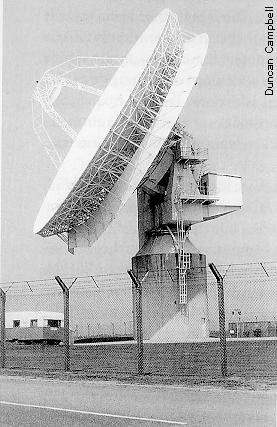

The Pacific Intelsat satellite was targeted by an NSA station built on a high One of two dishes at a British spy station in Cornwall that between them intercepted all Atlantic and Indian Ocean satellite phone and telex until the early 1980s. Duncan Campbell 31 basalt tableland inside the 100,000-hectare United States Army Yakima Firing Centre, in Washington State in the north-west United States, 200 kilometres south-west of Seattle. Also established in the early 1970s, the Yakima Research Station initially consisted of a long operations building and the single large dish. In 1982, a visiting journalist noted that the dish was pointing west, out above the Pacific to the third of the three Intelsat positions.3

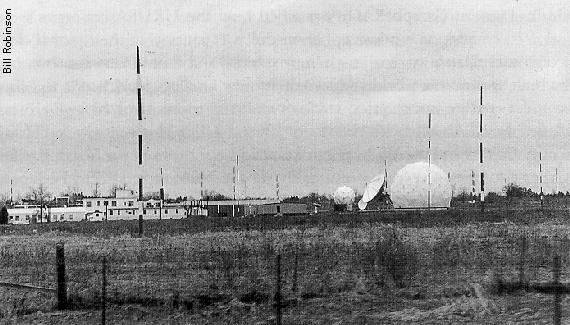

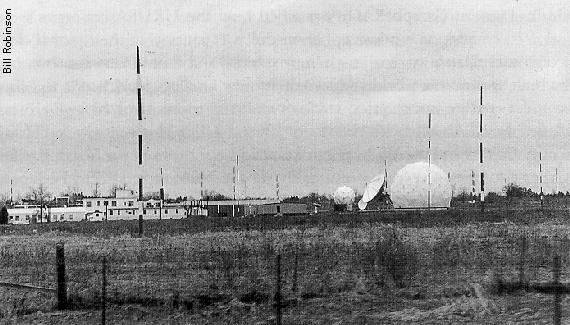

Yakima is located between the Saddle Mountains and Rattlesnake Hills, in a desert of canyons, dunes and sheer rock cliffs, where the only vegetation is grass. The Army leases the land to ranchers who herd their cattle in the shadow of the dishes. When visited in mid-1995 the Yakima station had five dish antennae, three facing westwards over the Pacific Ocean and two, including the original large 1970s dish, facing eastwards. Besides the original operations building there were several newer buildings, the largest of them two-storey, concrete and windowless.

Two of the west-facing dishes are targeted on the main Pacific Intelsat satellites; the Yakima station has been monitoring Pacific Intelsat communications for the NSA ever since it opened. The orientation of the two east-facing dishes suggests that they may be targeted on the Atlantic Intelsats, intercepting communications relayed towards North and South America. One or both may provide the link between the station and the NSA headquarters in Washington. The fifth dish at the station is smaller than the rest and faces to the west. Given its size and orientation, it appears to be the UKUSA site for monitoring the Inmarsat-2 satellite that provides mobile satellite communications in the Pacific Ocean area. If so, this is the station that would, for example, have been monitoring Greenpeace communications during the nuclear testing protests in the waters around Moruroa Atoll in 1995.

The GCSB has had important links with the Yakima station since 1981, when the GCSB took over a special, highly secret area of intelligence analysis for the UKUSA network (see Chapter 6). Telexes intercepted using Yakima’s single dish were first sorted by the Yakima computers, and then subjects allocated to New Zealand were sent to the GCSB for analysis. The Yakima station had been using Dictionary-type computers for this searching work for many years before the full ECHELON system was operating.

Between them, the Morwenstow and Yakima stations covered all Intelsat interception during the 1970s. But a new generation of Intelsat satellites launched from the late 1970s required a new configuration of spy stations. The Intelsat 4A and 5 series satellites differed from earlier ones in that they did not transmit only to the whole of the side of the world within their view; they now also had ‘east and west hemispheric’ beams that transmitted separately.4 For example, Intelsat 510, which operated above the Pacific until its replacement in December 1994, had one ‘global’ beam covering the whole region, but all the other transmissions went either to the east or to the west Pacific. Yakima was not within the ‘footprint’ of any hemispheric beams covering Australasia, South East Asia and East Asia, making interception of these signals difficult or impossible.

These changes to Intelsat design meant that the UKUSA alliance required at least two new stations to maintain its global coverage. Again the GCHQ provided one and the NSA one. A new NSA station on the east coast of the United States would cover Atlantic Intelsat traffic beamed down towards North and South America (Morwenstow covered the eastern Atlantic), and a GCHQ station in Hong Kong would cover both the western hemisphere of the Pacific Intelsats and the eastern hemisphere of the Indian Ocean Intelsats.[I do not imagine that Five Eyes wants to give up Hong Kong,and adds perspective to current affairs there for sure D.C 9/4/19]

The site chosen for the new NSA station was hidden in the forested South Fork Valley in the mountains of West Virginia, about 250 kilometres southwest from Washington DC, on the edge of the George Washington National Forest, near the small settlement of Sugar Grove. The site had been used in the 1950s and early 1960s for a failed attempt to spy on Russian radio communications and radars by means of reflections from the moon. The current satellite interception station was developed during the late 1970s, when a collection of new satellite dishes (from 10 to 45 metres in diameter) and the new windowless Raymond E. Linn Operations Building were constructed. It also incorporated a two-storey underground operations building already at the site. It started full operations about 1980.5

Like Morwenstow and Yakima, Sugar Grove is only 100 kilometres from an international satellite communications earth station, making it easy to intercept any ‘spot’ beams directed down to the legitimate stations. In this case it is the Etam earth station, the main link in the United States with the Intelsat satellites above the Atlantic Ocean.

The other new station, in Hong Kong, was constructed by the GCHQ also in the late 1970s. The station, which has since been dismantled, was perched above the sea on the south side of Hong Kong Island, across Stanley Bay from the British Stanley Fort military base and right next to high-rise apartments and luxury housing. In crowded Hong Kong the station’s anonymity was assured simply because there are so many satellite dishes scattered over the island. What helped to give away this one was the sign, on the entrance to an exclusive housing enclave across the bay, saying that taking photographs is strictly forbidden. When one of the Indian guards on the gate was asked why it was forbidden to take photos of a housing area, he pointed across the bay and said in serious tones, ‘Communications facility—very, very secret’.

The Hong Kong station had several satellite dishes and buildings, including a large windowless concrete building (similar to the ones at Yakima and Sugar Grove) and a collection of administration and operations buildings running down the hill into the base from the gates. Intelsat communications intercepted at the station were seen regularly by GCSB operations staff in Wellington.6

When visited in August 1994, the station fitted the requirements of the Intelsat monitoring network. It had one dish pointing up east towards the Pacific Intelsats, another towards the Indian Ocean Intelsat's and a third, for the station’s own communications, pointing up to a United States Defence Satellite Communications System satellite above the Pacific. Other dishes had perhaps already been removed. Dismantling of the station began in 1994—to ensure it was removed well before the 1997 changeover to Chinese control of Hong Kong—and the station’s staff left in November that year. News reports said that the antennae and equipment were being shipped to the DSD-run Shoal Bay station in Northern Australia, where they would be used for intercepting Chinese communications.

It is not known how the Hong Kong station has been replaced in the global network. One of the Australian DSD stations—either Geraldton or Shoal Bay—may have taken over some of its work, or it is possible that another north-east Asian UKUSA station moved into the role. For example, there were developments at the NSA’s Misawa station in northern Japan in the 1980s that would fit well with the need for expanded Intelsat monitoring.7

Throughout the 1980s a series of new dishes was also installed at the Morwenstow station, to keep up with expansion of the Intelsat network. In 1980 it still required only the two original dishes, but by the early 1990s it had nine satellite dishes: two inclined towards the two main Indian Ocean Intelsats, three towards Atlantic Ocean Intelsat's, three towards positions above Europe or the Middle East and one dish covered by a radome.

The Morwenstow, Yakima, Sugar Grove and Hong Kong stations were able to provide worldwide interception of the international communications carried by Intelsat throughout the 1980s. The arrangement within the UKUSA alliance was that, while the NSA and GCHQ ran the four stations, each of the five allies (including the GCSB) had responsibility for analysing some particular types of the traffic intercepted at these stations.

Then, in the late 1980s, another phase of development occurred. It may have been prompted by approaching closure of the Hong Kong station, but a more likely explanation is that, as we have seen, technological advances in the target Intelsat satellites again required expansion of the network.

Two UKUSA countries were available to provide southern hemisphere coverage: Australia and New Zealand. One of the new southern hemisphere stations would be the GCSB’s Waihopai station and the other would be at Geraldton in West Australia. (Both stations are described in detail later.) The new stations were operating by 1994 when the new Intelsat 7s began to be introduced. Waihopai had opened in 1989, with a single dish, initially covering one of the older generation of Intelsat satellites.

The positioning of the Geraldton station on Australia’s extreme west coast was clearly to allow it to cover the Indian Ocean Intelsats (they all lie within 60 degrees of the station, which allows good reception). Geraldton opened in 1993, with four dishes, covering the two main Indian Ocean Intelsats (at 60 degrees and 63 degrees) and possibly a new Asia-Pacific Intelsat introduced in 1992. It also covers the second of the two Pacific Intelsats, Intelsat 703.

New GCSB operations staff attend training sessions that cover the ECHELON system, showing how the GCSB fits into the system and including maps showing the network of UKUSA stations around the world. The sessions include briefings on the Intelsat and the maritime Inmarsat satellites — their locations, how they work, what kinds of communications they carry and the technical aspects of their vulnerability to spying. This is because these are primary targets for the UKUSA alliance in the Pacific.

But the interception of communications relayed by Intelsat and Inmarsat is only one component of the global spying network co-ordinated by the ECHELON system. Other elements include: radio listening posts, including the GCSB’s Tangimoana station; interception stations targeted on other types of communications satellites; overhead signals intelligence collectors (spy satellites) like those controlled from the Pine Gap facility in Australia; and secret facilities that tap directly into land-based telecommunications networks.

What Waihopai, Morwenstow and the other stations do for satellite communications, another whole network of intercept stations like Tangimoana, developed since the 1940s, does for radio.

There are several dozen radio interception stations run by the UKUSA allies and located throughout the world. Many developed in the early years of the Cold War and, before satellite communications became widespread in the 1980s, were the main ground signals intelligence stations targeting Soviet communications. Some stations were also used against regional targets. In the Pacific, for example, ones with New Zealand staff were used to target groups and governments opposed by Britain and the United States through a series of conflicts and wars in South East Asia.

A recent new radio interception station is the Australian DSD station near Bamaga in northern Queensland, at the tip of Cape York. It was set up in 1988 particularly to monitor radio communications associated with

UKUSA network of stations Waihopai Geraldton (Hong Kong) Sugar Grove Yakima Morwenstow the conflict between Papua New Guinea and the secessionist movement in Bougainville.9 GCSB staff are also aware of Australian intercept staff posted in the early 1990s to the recently opened Tindal Air Force base in northern Australia, suggesting that an even newer—as yet undisclosed—DSD intercept station may have been established there.

There is a wide variety of these radio interception operations. Some are very large, with hundreds of staff; others are small—a few staff hidden inside a foreign embassy bristling with radio aerials on the roof; others (like the Bamaga station) are unstaffed, with the signals automatically relayed to other stations. Because of the peculiarities of radio waves, sometimes stations far from the target can pick up communications that closer ones cannot.

Each station in this network—including the GCSB’s Tangimoana station—has a Dictionary computer like those in the satellite intercept stations. These search and select from the communications intercepted, in particular radio telexes, which are still widely used, and make these available to the UKUSA allies through the ECHELON system.

The UKUSA network of HF stations in the Pacific includes the GCSB’s Tangimoana station (and before it one at Waiouru), five or more DSD stations in Australia, a CSE station in British Columbia, and NSA stations in Hawaii, Alaska, California, Japan, Guam, Kwajalein and the Philippines. The NSA is currently contracting its network of overseas HF stations as part of post-Cold War rationalisation. This contraction process includes, in Britain, the closure of the major Chicksands and Edzell stations.

The next component of the ECHELON system covers interception of a range of satellite communications not carried by Intelsat. In addition to the six or so UKUSA stations targeting Intelsat satellites, there are another five or more stations targeting Russian and other regional communications satellites. These stations are located in Britain, Australia, Canada, Germany and Japan. All of these stations are part of the ECHELON Dictionary system. It appears that the GCHQ’s Morwenstow station, as well as monitoring Intelsat, also targets some regional communications satellites.

United States spy satellites, designed to intercept communications from orbit above the earth, are also likely to be connected into the ECHELON system. These satellites either move in orbits that criss-cross the earth or, like the Intelsats, sit above the Equator in geostationary orbit. They have antennae that can scoop up very large quantities of radio communications from the areas below.

The main ground stations for these satellites, where they feed back the information they have gathered into the global network, are Pine Gap, run by the CIA near Alice Springs in central Australia, and the NSA-directed Menwith Hill and Bad Aibling stations, in England and Germany respectively.10 These satellites can intercept microwave trunk lines and short-range communications such as military radios and walkie-talkies. Both of these transmit only line of sight and so, unlike HF radio, cannot be intercepted from faraway ground stations.

The final element of the ECHELON system are facilities that tap directly into land-based telecommunications systems, completing a near total coverage of the world’s communications. Besides satellite and radio, the other main method of transmitting large quantities of public, business and government communications is a combination of undersea cables across the oceans and microwave networks over land. Heavy cables, laid across the seabed between countries, account for a large proportion of the world’s international communications. After they emerge from the water and join land-based microwave networks, they are very vulnerable to interception.

The microwave networks are made up of chains of microwave towers relaying messages from hilltop to hilltop (always in line of sight) across the countryside. These networks shunt large quantities of communications across a country. Intercepting them gives access to international undersea communications (once they surface) and to international communication trunk lines across continents. They are also an obvious target for large-scale interception of domestic communications.

Because the facilities required to intercept radio and satellite communications—large aerials and dishes—are difficult to hide for too long, that network is reasonably well documented. But all that is required to intercept land-based communication networks is a building situated along the microwave route or a hidden cable running underground from the legitimate network. For this reason the worldwide network of facilities to intercept these communications is still mostly undocumented.

Microwave communications are intercepted in two ways: by ground stations, located near to and tapping into the microwave routes, and by satellites. Because of the curvature of the earth, a signals intelligence satellite out in space can even be directly in the line of a microwave transmission. Although it sounds technically very difficult, microwave interception from space by United States spy satellites does occur.11

A 1994 exposé of the Canadian UKUSA agency called Spyworld,12 coauthored by a previous staff member, Mike Frost, gave the first insights into how much microwave interception is done. It described UKUSA ‘embassy collection’ operations, where sophisticated receivers and processors are secretly transported to their countries’ overseas embassies in diplomatic bags and used to monitor all manner of communications in the foreign capitals.

Since most countries’ microwave networks converge on the capital city, embassy buildings are an ideal site for microwave interception. Protected by diplomatic privilege, embassies allow the interception to occur from right within the target country.13 Frost said the operations particularly target microwave communications, but also other communications including car telephones and short-range radio transmissions.

According to Frost, Canadian embassy collection began in 1971 following pressure from the NSA. The NSA provided the equipment (on indefinite loan), trained the staff, told them what types of transmissions to look for on particular frequencies and at particular times of day and gave them a search list of NSA keywords. All the intelligence collected was sent to the NSA for analysis. The Canadian embassy collection was requested by the NSA to fill gaps in the United States and British embassy collection operations, which were still occurring in many capitals around the world when Frost left the CSE in 1990.

Separate sources in Australia have revealed that the DSD also engages in embassy collection. Leaks in the 1980s described installation of ‘extraordinar- 39 ily sophisticated intercept equipment, known as Reprieve’ in Australia’s High Commission in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea and in the embassies in Indonesia and Thailand. The operations are said to take a whole room of the embassy buildings and to be able to listen to local telephone calls at will.14 There is good reason to assume that these operations, too, were prompted by and supported with equipment and technical advice from the NSA and GCHQ.

Of course, when the microwave route is across one of the UKUSA countries’ territory it is much easier to arrange interception. For example, it is likely that there is a GCHQ operation intercepting, and feeding through Dictionary computers, all the trans-Atlantic undersea cable communications that come ashore in Cornwall.

Menwith Hill, sitting in northern England, several thousand kilometres from the Persian Gulf, was awarded the NSA’s Station of the Year prize for 1991 following its role in the Gulf War. It is a station which affects people throughout the world.

In the early 1980s James Bamford uncovered some information about a worldwide NSA computer system codenamed Platform which, he wrote, ‘will tie together fifty-two separate computer systems used throughout the world. Focal point, or “host environment”, for the massive network will be the NSA headquarters at Fort Meade. Among those included in Platform will be the British SIGINT organisation, GCHQ.’17

There is little doubt that Platform is the system that links all the major UKUSA station computers in the ECHELON system. Because it involves computer-to-computer communications, the GCSB and perhaps DSD were only able to be integrated into the system in the 1990s when the intelligence and military organisations in the two countries changed over to new computer-based communications systems.

The worldwide developments, of which construction of the Waihopai station was part, were coordinated by the NSA as Project P415. Although most of the details remained hidden, the existence of this highly secret project targeting civilian communications was publicised in August 1988 in an article by Duncan Campbell. He described how the UKUSA countries were ‘soon to embark on a massive, billion-dollar expansion of their global electronic surveillance system’, with ‘new stations and monitoring centres ... to be built around the world and a chain of new satellites launched’.

The satellite interception stations reported to be involved in P415 included the NSA’s Menwith Hill station, the GCHQ’s Morwenstow and Hong Kong stations and the Waihopai and Geraldton stations in the South Pacific. Other countries involved, presumably via the NSA, were said to be Japan, West Germany and, surprisingly, the People’s Republic of China.

‘Both new and existing surveillance systems are highly computerised,’ Campbell explained. ‘They rely on near total interception of international commercial and satellite communications in order to locate the telephone and other target messages of target individuals....’18

There were two components to the P415 development, the first being the new stations required to maintain worldwide interception. More striking, though, was the expansion of the NSA’s ECHELON system, which now links all the Dictionary computers of all the participating countries.

The ECHELON system has created an awesome spying capacity for the United States, allowing it to monitor continuously most of the world’s communications. It is an important component of its power and influence in the post-Cold War world order, and advances in computer processing technology continue to increase this capacity.

The NSA pushed for the creation of the system and has the supreme position within it. It has subsidised the allies by providing the sophisticated computer programmes used in the system, it undertakes the bulk of the interception operations and, in return, it can be assumed to have full access to all the allies’ capabilities.

Since the ECHELON system was extended to cover New Zealand in the late 1980s, the GCSB’s Waihopai and Tangimoana stations—and indeed all the British, Canadian and Australian stations too—can be seen as elements of a United States system and as serving that system. The GCSB stations provide some information for New Zealand government agencies, but the primary logic of these stations is as parts of the global network.

On 2 December 1987, when Prime Minister David Lange announced plans to build the Waihopai station, he issued a press statement explaining that the station would provide greater independence in intelligence matters: ‘For years there has been concern about our dependence on others for intelligence—being hooked up to the network of others and all that implies. This government is committed to standing on its own two feet.’

Lange believed the statement. Even as Prime Minister, no one had told him about the ECHELON Dictionary system and the way that the Waihopai station would fit into it. The government was not being told the truth by officials about New Zealand’s most important intelligence facility and was not being told at all about ECHELON, New Zealand’s most important tie into the United States intelligence system. The Waihopai station could hardly have been more ‘hooked up to the network of others’, and to all that is implied by that connection.

next

THE POWER OF THE DICTIONARY INSIDE ECHELON

2

HOOKED UP TO THE

NETWORK

THE UKUSA SYSTEM

Ten years later, on Saturday, 15 January 1994, technicians in satellite earth

stations around the Pacific were busy tuning their equipment to a new satellite. The first of the new generation of Intelsat 7 series satellites, it had been

launched several weeks before, from the European Kourou air base in French

Guyana, and then manoeuvred into position far out in space above the Equator at 174 degrees east, due north of New Zealand above Kiribati. The 20 Intelsat (International Telecommunications Satellite Organisation) satellites that ring the world above the Equator carry most of the world’s satellite-relayed international phone calls and messages such as faxes, e-mail and telexes. The new satellite, Intelsat 701, replaced the 10-year-old Intelsat 510 in the same position. The changeover occurred at 10 pm New Zealand time that summer evening.

The Waihopai station — part of a super-secret global system called ECHELON

—

automatically intercepts satellite communications for the foreign allies.

The Labour

government that approved the station was not told about these links.

At the GCSB’s station at Waihopai, near Blenheim in the north of the

South Island, the radio officer staff were just as busy that evening, setting

their special equipment to intercept the communications which the technicians in legitimate satellite earth stations would send and receive via the new

satellite. These specially trained radio officers, who learned their skills at the Tangimoana station, usually work day shifts, but on 15 January 1994 they

worked around the clock, tuning the station’s receivers to the frequency

bands the GCSB wanted to intercept, selecting the specific channels within

each band that would yield the types of messages sought within the UKUSA

network and then testing that the high-tech intelligence collection system

was working smoothly. That satellite changeover was a very significant event

for the Waihopai station and the GCSB. Although it would always be only

a small component of the global network, this was the moment when the

station came into its own. There have been various guesses and hints over the years about what the Waihopai station was set up to monitor—‘sources’ in one newspaper said foreign warship movements; a ‘senior Telecom executive’ told another newspaper it was most likely ‘other countries’ military communications’— but, outside a small group of intelligence staff, no one could do more than theorise. Waihopai was established specifically to target the international satellite traffic carried by Intelsat satellites in the Pacific region and its target in the mid-1990s is the Intelsat 701 that came into service in January 1994, and is the primary satellite for the Pacific region.

Intelsat satellites carry most of the satellite traffic of interest to intelligence organisations in the South Pacific: diplomatic communications between embassies and their home capitals, all manner of government and military communications, a wide range of business communications, communications of international organisations and political organisations and the personal communications of people living throughout the Pacific. The Intelsat 7 satellites can carry an immense number of communications simultaneously. Where the previous Intelsat 5s could carry 12,000 individual phone or fax circuits at once, the Intelsat 7s can carry 90,000. All ‘written’ messages are currently exploited by the GCSB. The other UKUSA agencies monitor phone calls as well.