WEDGE

FROM PEARL HARBOR TO 9/11

HOW THE SECRET WAR

BETWEEN THE FBI AND CIA

HAS ENDANGERED NATIONAL SECURITY

MARK RIEBLING

CHAPTER SEVEN

THE GRAY GHOST

IAN FLEMING’S FAVORITE NOVELIST, John Buchan, created in

The Thirty-nine Steps a character for whom one whole

chapter was named: “The Dry-Fly Fisherman.” Richard

Hannay, the hero of Buchan’s stories, met him at a

waterfall. The fisherman nodded to Hannay, leaned his

delicate ten-foot split-cane rod against a nearby bridge,

and stared at the surface of the waters. His kind blue eyes

seemed to go very deep. He had a square, cleft jaw and a

broad, lined brow; Hannay had never seen a shrewder

face. But his hair was prematurely gray and thin about the

temples, and there were lines of overwork below the eyes;

his big frame seemed built for a much heavier man, his

shoulders were stooped, and his skin was drained of color,

like that of someone who got too little fresh air. He made

a few cryptic remarks, then invited Hannay into his adjacent country home; they drank good champagne,

dined, and smoked. Hannay’s host swung his long legs

over the side of a chair and identified himself as Sir

Walter Bullivant, the country’s counterintelligence chief.

He would become Hannay’s mentor and boss, and the

prototype for master spy-catchers in fiction and in fact.

If Fleming himself never really made a Bullivant type

the focus of his fictions—“the white-collar boys” could

“catch spies,

” while Agent 007 would attack SMERSH,

“the threat that made them spy”—that was one reason the

Bond books would be dismissed by Dulles and others as

“unrealistic.” Dulles did not think that professional

intelligence officers, as a rule, went on “perilous or

glamorous missions” or became involved with “luscious

dames.” He would, however, say: “A useful analogy is to

the art of angling. The fisherman’s preparation for the

catch, his consideration of the weather, the light, the

currents, the depth of the water, the right bait or fly to use,

the time of day to fish, the spot he chooses and the

patience he shows are all a part of the art and essential to

success. In fact, I have found that good fishermen tend to

make good intelligence officers.”

So it was with the man whom Dulles thought CIA’s best intelligence officer of all, a dry-fly fisherman who much resembled Buchan’s Bullivant. For the twenty years following December 20, 1954, he would be the FBI’s main point of liaison. His separate peace with Papich would help break a network of Soviet agents in New York, lead the two agencies into a joint project to open the mail of U.S. citizens, and limit fallout when the FBI’s prize spy prisoner was swapped for a CIA pilot downed in Russia. Yet he would also bring to the Agency a way of thinking that crystallized FBI-CIA differences, and which would ultimately rip relations apart.

BY SUMMER 1954, a whole slew of traumas and setbacks had demonstrated the need for a revamped national counterintelligence effort. The Bentley, Hiss, Fuchs, and Rosenberg cases had destroyed the country’s early naivete. The Burgess-Maclean affair alerted the intelligence establishment that its secrets could go, even if its own operations weren’t penetrated. The McCarthyism period brought home the need to prevent such morale sapping episodes by prophylactic measures. That need was felt particularly acutely by Houston, Edwards, and others concerned with personnel security at CIA, who had tangled with the FBI over Offie and Meyer and various loyalty cases, and who didn’t feel the Agency was getting proper investigative help from the Bureau. It was not so much a lack of help, as the wrong kind. CIA was all for getting tips from Hoover, but wanted to handle its own security problems internally, without the Bureau or HUAC or anyone else sneezing into the soup.

A start at reform had been made in June, when Dulles and Hoover worked out, via Houston and Attorney General William P. Rogers, a procedure for FBI investigation of “irregularities” involving CIA employees. Misconduct of any kind was to be the province of CIA’s Office of Security, which had to jump into a situation immediately—not only to preserve CIA’s public reputation, but to protect secrets which might be compromised by the curiosity of the FBI. Every so often, some CIA officer would fall afoul of the administrative charter, or, on rare occasions, flee an automobile accident, or leave a satchel full of classified documents in a taxicab, and Papich would turn the case over to Sheffield Edwards. One CIA officer had to resign after the FBI discovered that his house was stacked to the ceiling with secret government papers; he wasn’t passing them out to the enemy, just building up a library for himself, for writing books, and apparently it helped him, because he later became a top expert in foreign policy. The Bureau could have recommended that the man be prosecuted for unlawful possession of government documents, but CIA’s policy was to handle and resolve everything internally, fearing that secrets would be lost through the “discovery” process in a trial, and the FBI went along.

But DCI Dulles knew that counterintelligence involved more than just letting the Agency take care of its own; it mattered what kind of care was taken. There was a demonstrable need to be more cautious, more concerned with the principles of compartmentalization and “need to know.” If Dulles’ people were going to succeed, the security of sources, operations, and personnel was everything. That was the lesson taught by Wisner’s OPC, at least in the view of William Harvey’s counterintelligence people. If Cord Meyer was trying to suborn the editor of a newspaper, or Wisner to work with a guerrilla leader in the mountains, it was crucial to know whether one’s agent might be an informant for the security service. But OPC wanted only action. As one of Harvey’s colleagues was admonished, “Goddamn it, we don’t want counterintelligence, we want guerrillas!” Because of progress in radio detection, and because the adversary controlled Trust-style opposition groups, the task of infiltrating commandos was more difficult than it had been even ten years earlier—yet there didn’t seem to be any shift in tactics from world war to Cold War. Wisner’s men were still fighting the Nazis, still dropping people behind the lines, and it took the spectacular failures of OPC’s covert actions, in Poland, Albania, and the Ukraine, to teach the wisdom of Harvey’s more cautious approach.

Additional pressures came from outside the Agency. The White House was getting mail urging that Hoover be made director of CIA, or that the Agency be folded into the FBI; J. Edgar would kick out the commies as he had chased down Dillinger, and only then would the nation’s secrets be safe. One concerned citizen complained that CIA had been puffed into existence by Donovan’s press campaign, and that Hoover’s more efficient SIS had been taken over by the Agency because Hoover refused to publicize the FBI’s successes; “the public and even Congress never even heard of [SIS], nor did it get any publicity, nor did J. Edgar Hoover or the men in charge get pictures in the paper entitled ‘Superspy.’ ” Eisenhower responded to the pressure as any politician would, by appointing a committee to look into it. The inquiry was headed by Lieutenant General James Doolittle, and the sixty-nine-page Doolittle Report, presented to Eisenhower in September 1954, proposed some radical reforms.

Most signally, the report urged CIA to assume the country’s leading counterintelligence role. The National Security Council had given the job of collating counterintelligence to CIA in December 1947, but there was a consensus, Harvey’s Staff C notwithstanding, that countering enemy intelligence was the FBI’s job. That would have to change. The United States needed to abandon the law-enforcement route for a “more ruthless” approach, the Doolittle Report stressed, and that new ruthlessness must be applied to “intensification of CIA’s counterintelligence efforts to prevent or detect and eliminate penetrations.” The situation required a new strategy, a new concept for American life, one which would spill across normally restricted areas, legal channels, and departmental lines.

It also required a new chief of counterintelligence, for in mid-1953 Harvey had been made Chief of Base in Berlin. The outgoing Bedell Smith had told Papich early that year that Harvey was probably going to be posted abroad. “As you know, ” Hoover was reminded in a summary of that conversation, “[Harvey] has been the center of many controversies.” But there was more to the decision than a desire to keep Harvey out of Hoover’s way. Harvey himself had wanted to leave Staff C, because he hoped to rise in the Agency and, compared with other disciplines, counterintelligence was considered career ending. Harvey didn’t have much of a chance to manage people, the way he would if he were running agents in even the smallest foreign station, and thus wasn’t as easily marked for promotion; already, while he was stalled in Staff C, two less knowledgeable men with overseas experience had overtaken him. He added an extra martini at lunch, and when the chief ship of Berlin Base came free, he asked for the job and got it. Divided into Russian, British, French, and American zones, isolated in the heartland of communist Germany, Berlin was the hotbed of the Cold War. It was, too, a welcome reprieve from the hassles and obstructionism of the FBI. It would be almost nine years before Harvey worked again in Washington, though, as he would find, that was not long enough to outrun Hoover’s memory.

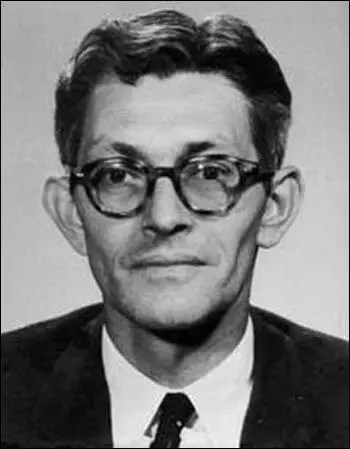

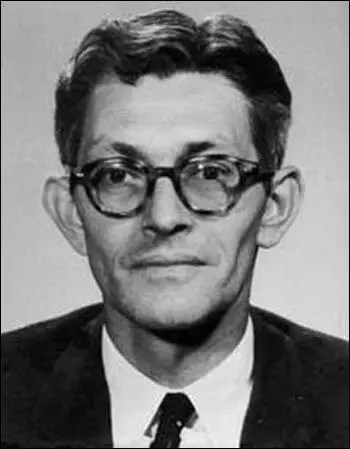

SAM PAPICH MET CIA’s new counterintelligence chief in a large corner office of L Building, where a row of windows looked out on the Lincoln Memorial—or would have, if Venetian blinds had not been shut against the light. Six secretaries in the anteroom testified to the new appointee’s power, as did the long row of black safes in his inner sanctum, and the piles of documents. Red priority stickers were everywhere in the mass of papers, like poppies pushing through a field of snow. In all other respects, the office lacked distinctiveness, typical CIA; there wasn’t much on the walls. But in a high leather-backed chair behind the desk was as singular a man as Papich had ever seen.

His black hair was slicked back from a pale forehead, a

bony blade of nose, sunken cheeks, and elegantly pointed

chin—a chiseled, cadaverous face that had been proposed,

only half facetiously, as a logo for CIA. His deep-set eyes

were emphasized by arched brows, framed by horn rimmed bifocals, and lit with a kind of controlled fire. He

was thirty-seven years old, and well over six feet tall, but

his gaunt frame was stooped and slightly twisted, making

him seem, as one colleague said, half his height and twice

his age. Clasped to his shirt pocket was a plastic picture ID, required wearing for anyone inside headquarters, and

around its edges were twenty-four boxes filled with red

letters, signifying the security clearances that gave him

access to more restricted areas, and more secrets, than any

man except the Agency’s director.

His black hair was slicked back from a pale forehead, a

bony blade of nose, sunken cheeks, and elegantly pointed

chin—a chiseled, cadaverous face that had been proposed,

only half facetiously, as a logo for CIA. His deep-set eyes

were emphasized by arched brows, framed by horn rimmed bifocals, and lit with a kind of controlled fire. He

was thirty-seven years old, and well over six feet tall, but

his gaunt frame was stooped and slightly twisted, making

him seem, as one colleague said, half his height and twice

his age. Clasped to his shirt pocket was a plastic picture ID, required wearing for anyone inside headquarters, and

around its edges were twenty-four boxes filled with red

letters, signifying the security clearances that gave him

access to more restricted areas, and more secrets, than any

man except the Agency’s director.

James Jesus Angleton was one of only a handful of people—Harvey was another—who would ever become truly legendary within the faceless bureaucracy of knowledge that was CIA. A chain-smoking poetry enthusiast, ace fly-fisherman, and grower of rare orchids, Angleton had been recruited into OSS after graduating from Yale. He had served under Norman Pearson in X-2 and had been particularly adept at burning and turning Nazi stay-behinds in Italy. After the war, he had been put in charge of a so-called Special Desk to handle such tasks as liaison with the Israelis and the British. That latter experience had stamped him with a general auspiciousness, for he had lunched regularly with Kim Philby and detected nothing until it was too late. Some of his Special Desk duties had also caused Angleton to clash with DeLoach the few times they met, so Papich was not entirely surprised that when he first encountered Angleton, in that corner office of L Building, they got into “a real fight.”

After preliminary greetings, the new counterintelligence chief lit a cigarette, leaned across his desk, and, in his gravelly burr, brought up a case that had allegedly been mishandled by the Bureau. It had been damaging to CIA, and Angleton made a big deal about it —maybe with good reason, but Papich disagreed with him. It got to a bitter stage; they were shouting insults. Finally, Papich just walked out. Maybe Angleton was testing him, to make clear that he was going to dominate liaison. Well, thought Papich, he’s not going to.

They saw each other again the next day, and managed to act cordially. Before too long, small talk brought out that they were from neighboring big-sky states, and they both liked fly-fishing. They went off one weekend to do a little angling for brown trout in the freestone streams of West Virginia, and after that they were friends. Papich was impressed by the fact that Angleton would never just cast a fly; he would always spend a half-hour or so just stalking along the riverbank, examining the insect life, and then craft lures to imitate the species along that particular stretch of shore—brown ants, inchworms, soldier beetles, whatever he saw. Angleton had mastered the esoteric lore and literature of the discipline, which dated back to fifteenth-century Scotland; he could loop his line through the air and splash it onto the waters just so, in imitation of a hatching fly, and his vest and hat were decorated with traditional fly designs, in all their exotic colors and types and names: Flamingo Zonker, Yellow Goofus Bug, Egg-Sucking Leach. Angleton knew them all, but his standby was the Gray Ghost, a classic American freestone-river design—ocher floss-silk body ribbed with flat silver tinsel, black silk nose, white buck tail, and gray cock hackles sweeping sleekly back, like wings. Given Angleton’s own spookish demeanor and suspicious outlook, “Gray Ghost” became one of his nicknames, and colleagues thought it the one that fit him best.

The fishing trips sealed what would become a close working relationship, and Papich became a serious student of Angleton’s counterintelligence philosophy. To Angleton, catching spies was much like landing trout. It was all about patience, research, deception. Yet CI was not merely a body of knowledge; it was also a way of seeing things. It meant transcending the details of a case, putting tactical problems in a strategic perspective, gaining a larger view. Angleton felt that too much of the country’s conception of CI, as promoted by detective entertainments and the FBI’s own actions, was “spy versus spy.” That was like fighting soldier-to-soldier using bayonets, as opposed to understanding why the soldiers were being put face to face. That was counterespionage, not counterintelligence. What CI really required, most of all, was a good dollop of focused historical research—not the random digestion of massive mounds of fact, but purposeful, teleological analysis, looking for patterns over a long period of time. His work against the Nazis had taught him that patient accumulation of fact allowed one to decipher the enemy’s thinking, and thus anticipate his moves. If one could not read the enemy’s files, one could at least read his mind.

Trying to read the Soviet mind on CIA-FBI relations, Angleton considered it logical that the KGB would try to split America’s CI community along its pre-existent fault line. “When the enemy is united, divide him”—so the ancient Chinese strategist Sun Tzu had counseled in The Art of War—a work which, through the Mongol-Tartars, had greatly influenced Russian strategy, and which, in English translation, Angleton had read more than once. “Drive a wedge … Separate the enemy’s allies from him. Make them mutually suspicious so that they drift apart. Then you can plot against them.” The West itself was trying to split Romania and Hungary from Moscow, and to play Soviet military intelligence (the GRU) against the KGB. Just so, Angleton reasoned, the Soviets wanted to sow schisms between the Americans and the British, and between CIA and FBI. “That was part and parcel of Jim’s basic philosophy—he didn’t want that to happen, ” Papich would later say. “It was one of the worst things that could happen, because once you destroy a relationship between services, you’ve destroyed the effectiveness of both services.”

Though the CI chief was not yet sure exactly how the Soviets would make inter-agency trouble, he guessed they would try to capitalize on a “dissociation of sensibility.” (The phrase came from a famous essay by Angleton’s favorite poet, T. S. Eliot, who used it to describe thematic dualism's in literature; Angleton used it to describe the tension between Hoover’s law-enforcement mentality and CIA’s double-agent approach.) Angleton also supposed the KGB would try to slip between jurisdictional cracks. Just as a fly-fisherman, spotting a brown trout nibbling near the surface of the shallows, would cast from beyond its field of vision, so would the Soviets profit from inter-agency blind spots. If such schemes were not thwarted by close liaison, American CI would be essentially at war with itself, and the game could be lost. “Counter-intelligence, ” Angleton liked to say, “is only as good as relations between the CIA and FBI.”

AN EARLY TEST of the new cooperation came when Papich tried to broker a joint FBI-CIA operation to kidnap a Soviet spy in the Middle East. Elizabeth Bentley had told Harvey back in 1946 that her controller, an American known to her only as “Jack, ” had been operating a big net of agents; by 1953, FBI counterintelligence man Robert Lamphere was sure that “Jack” was an American man named Joseph Katz. Subpoenaed by HUAC, Katz had fled to Israel, where, being of the Jewish faith, he was automatically eligible for citizenship. The U.S. did not have an extradition treaty with Israel, but Angleton’s close ties to Israeli intelligence offered certain possibilities. Lamphere had met Angleton back when he was running Special Desk, and though they had little direct contact, Lamphere had always got excellent results whenever he asked, via liaison, for Angleton to do something overseas. Now the three formulated a joint FBI-CIA operation to return Katz to the United States. The key to the operation would be luring Katz onto a U.S.-registered boat, outside Israel’s territorial waters, where Lamphere could make a legal arrest. It was going to be risky, but Lamphere outlined the plan in a memo to Hoover, who gave preliminary approval. “He didn’t like the idea of the joint CIA-FBI operation, ” Lamphere said, “but had been made to understand that the FBI did not have the resources or contacts in Israel to pull off this one, whereas the CIA did.”

Papich and Lamphere got all their shots, and were ready to fly to Israel, when Hoover took a last-hour look at the whole operation and scotched it. The FBI director told them that he’d talked to a deputy attorney general, and had got the distinct impression that Angleton had informed Justice of the plan. Feeling that this was supposed to be an FBI expedition, and that CIA had overstepped its jurisdiction by going to Justice, Hoover called the whole thing off. Angleton insisted that he’d never had any such conversation with Justice, and Lamphere told Hoover that Justice probably knew about it because he, Lamphere, had cut them a copy of the planning memo, but there was no moving the director.

Of course, the team was extremely disappointed. “I was chagrined on two counts, ” Lamphere remembered. “One, both Sam Papich and I had wanted this joint operation to improve relations between the FBI and the CIA—and the result had been just the opposite, a further rupture between the agencies. Two, I was disappointed that my one best hope to reopen the Bentley case and prosecute some of the key figures was now gone.” Lamphere was so disgusted with Hoover’s bullheadedness that he soon resigned from the Bureau.

Angleton also was peeved. He went to Papich and said, “Why the hell did the boss turn this one down?” Papich thought the director was probably concerned that another agency—and another foreign service, the Mossad—had too much operational control. He recounted how some botched operations with local police in the hunt for Dillinger had taught Hoover to participate in joint projects only if he could control the show. That didn’t wash too well with Angleton. It sickened him that, despite the best laid plans of FBI and CIA men, Soviet spies like Katz still could count on the “dissociation” of American counterintelligence.

RUNNING OPERATIONS SILENTLY, without Hoover’s direct knowledge, produced much better results. In one case, Angleton got the Bureau access to a New York mob lawyer. The man was a rascal, but there was no counting the cases the FBI prosecuted on the basis of his cooperation, all involving corruption within unions and city government—and all for free, just given over by Angleton. Papich also worked with CIA people on projects spearheaded by Angleton in the cryptographic field, while the Agency, for its part, serviced countless FBI requests for coverage of American communist leaders traveling abroad. Since the great majority of Soviet and Eastern-bloc operations against the U.S. were originated overseas, CIA was naturally able to supply more leads for the FBI than conversely, but the Agency got its share of dividends. Angleton would ask the Bureau to undertake “black bag” jobs against certain domestic targets, and the Bureau would sometimes do so.

But good relations at the working level were always constrained by tensions at the top. Angleton’s own relations with Hoover were cordial the few times they met, but looking back a quarter-century later, the CI chief would realize that during all those years, from the 1950s through the mid-1970s, “there weren’t more than three or four meetings” between Hoover and the directors of CIA, except where they bumped into one another at a national security conference. There was no question in Angleton’s mind but that this adversely affected CI. On the other hand, Angleton had to admit that Hoover had some good reasons to be wary of CIA. In October 1955, for instance, Papich carried over a letter from Hoover suggesting that Donald Maclean might have compromised CIA employees. Maclean had been “a frequent visitor” at CIA, according to a Bureau source, and was alleged to have “dated two of your stenographers.” An FBI search of logs kept by the door guards at CIA’s “O” Building, in front of the Lincoln Pool, showed that Maclean often entered that particular building after hours. While there was no firm proof that he had dated any CIA women, such episodes did not increase Hoover’s trust of CIA.

Hoover’s sometimes petty power plays were none too helpful, either. FBI man William Sullivan later alleged that the FBI planted stories critical of the CIA, and it appears that, in September 1955, the FBI director went public with the accusations against Philby in a way that embarrassed the Agency. Columnist Walter Winchell, a Hoover friend, reported on his popular Sunday-night radio show that Burgess and Maclean had escaped to Moscow after being tipped off by “another top British intelligence agent” who had been in Washington; Winchell said that “the FBI refused to give this man any information for over three years, ” which was false, but that “other American intelligence departments opened up their very secret files for him, ” which of course was true. Hoover also tried to sour the opinion of Joseph Kennedy about CIA in February 1956, when the Boston power-broker was named a member of the president’s Board of Consultants on Foreign Intelligence Activities. “I discussed with Mr. Kennedy generally some of the weaknesses which we have observed in the operations of CIA, ” Hoover told his top deputies after a private meeting in his headquarters office, “particularly as to the organizational-set-up and the compartmentalization that exists within that agency.” Nor would Hoover keep out of the Washington paper-mill Attorney General Rogers’July 28, 1958, statement that “he [Rogers] just wished the FBI was doing the intelligence work abroad instead of CIA.”

WITH THAT KIND OF SENTIMENT radiating down, it was unsurprising that the two agencies were unable to agree in some important areas, including the storage and retrieval of secrets. The issue arose because Angleton, shortly after becoming Chief/CI, started computerizing document on the huge vacuum-tube punch-card monsters then being made by IBM. With IBM’s help, he developed an innovative computerized microfilm file-index known as Walnut; the project began with Abwehr documents captured in World War II and spread from there. In 1955, Angleton persuaded Dulles to create a U.S. Intelligence Board Committee on Documentation (CODIB) to promote community-wide computerization, but the FBI was not interested in applying computers to its name-trace or identification work. “We’ve got three warehouses, full of papers, and files, and thousands of people, who can run around and work the files, ” Hoover’s CODIB man insisted. Nor did CODIB ever achieve inter-agency standards to ease the exchange of data; CIA and FBI couldn’t even agree on the order of “header” items in a biographic record. “Do you want last name first, then first name and middle initial, followed by date of birth, followed by place of birth?” That question was debated for eight years, and it was not surprising to those within bureaucratic Washington, let alone familiar with FBI-CIA difficulties, that during the entire existence of CODIB, from 1955 to 1963, so simple a problem was never resolved.

While CODIB stalled over minutiae, a deeper problem for centralized analysis stemmed from the FBI’s anti analytical bias. Rocca built an extensive research section, but the FBI’s, headed by Bill Sullivan, was comparatively small, and was directed mostly at the CPUSA, not the KGB. That always rankled Papich. “If, over a period of five years, X number of Soviets had visited New Mexico near Los Alamos, and had been seen driving around—well, who were they, what were their backgrounds? Could the Bureau draw any conclusion as to what the target was? What the hell did it all mean? We’d zero in on an individual, primarily to develop evidence for prosecution, but we did very little big-picture thinking. That all goes back to our law-enforcement nature.”

But if the Bureau was little interested in CIA’s historical research, Angleton’s CI shop, for its part, benefited greatly from FBI tips on the way the Soviets worked. For the first two years of Angleton’s tenure, the Bureau couldn’t tell CIA much it didn’t know already, but that began to change in 1957, when the Yale choir made its maiden trip to Moscow, and the Soviets began opening up, a little bit, to the world. After that, CIA had a lot to learn from the Bureau’s debriefings of returning American tourists. The real epiphany was to come that same year, when Angleton’s cooperation gave the Bureau its biggest break so far in the secret war against Soviet spies. Even so, it was a cooperation that would have to be hidden from Hoover—and the FBI would repay it by risking the safety of CIA’s only mole in Moscow.

Hayhannen claimed to belong to a network of spies in the New York City area, and identified himself as a Soviet “illegal.” In CI jargon, an illegal was any foreign intelligence officer dispatched to the United States under a false identity, in violation of immigration law. Although technically no spy openly declared his profession and all spying was against the law, most intelligence personnel were “legal” in the sense that they were affiliated with their home nation’s embassy and performed some nominal diplomatic functions to justify their presence in country. Illegals, by contrast, might enter the U.S. under totally fictitious identities, often taken from tombstones. They would never make open contact with their sponsors’ embassy, and could live relatively undetected, especially in a polyglot place like New York. Once past the customs barriers of his unwitting hosts, the saying went, a Soviet illegal disappeared like a diamond into an inkwell. It was assumed that illegals aimed to get employment that would permit easy access to scientific and technical information, and that they hoped to penetrate the intelligence community and perhaps even enter political life. Beyond that little was known, because the FBI had never caught a Soviet illegal, or had the chance to debrief one.

“I’m on my way into East Germany, for a meeting with my controllers, ” he told the CIA officer at Paris Station, “and I don’t want to go. I want to cooperate with the United States government.” Hayhannen’s bizarre behavior soon instilled doubts about whether that might be such a good idea, however. “I live in Peekskill, New York, ” he said, “and to prove I’m in Peekskill, I’m going to send a message to my wife.” Picking up his left hand, he began to beat out a message in Morse code on his chest. Christ, thought the CIA officer, this man is insane. But then Hayhannen showed an American passport obtained by using a false birth certificate, and started reeling off information—about his training, meetings he’d had in Vienna, identities of KGB officers, secret caches of funds. He even promised to lead the FBI to his Soviet controller, a mysterious Brooklyn resident known to him only as “Mark.”

This information was immediately cabled Blue-Bottle (highest security) from Paris Station to CIA headquarters in Washington. In essence the station chief said to Frank Wisner, who by then was deputy director for plans: We can’t hold him, we can’t detain him. We don’t want to get involved with the French. We want an immediate reply.

Wisner deferred to Angleton, who consulted Papich, who assessed the situation in Angleton’s basement at three in the morning. Papich thought he could get the cooperation of General Joseph Swing, head of the Immigration Service, to put Hayhannen in quarantine. If it was determined Hayhannen was a phony, they could always deport him. Certainly Hayhannen was an unstable character, and Hoover wasn’t about to bring him to the United States on his own, but a lot of Bureau cases could develop if they played it right. There was nothing really in it for CIA, except the risk of bringing in a “crazy” or a false defector, but finally Angleton just said, “Let’s get the character over here, and see what happens.”

Hayhannen was put on a plane from Paris. His CIA bodyguards almost ended up shooting him during the night flight across the Atlantic, because he was drunk and irrational and tried to kick some windows out of the plane. In fact, he was bombed most of the time, and it did not take long to grasp that he was an alcoholic. Once in America, he put down about a fifth of vodka every day, until the Bureau got him into quarantine. They then debriefed him about his boyhood in Finland and Leningrad, how he joined Soviet intelligence to “get ahead, ” his extensive training before coming to the U.S. in October 1952, and his work for the Soviets since then, mostly servicing dead-drops of other agents. His house in Peekskill was found to contain a codebook and secret writing materials. There was no question about it, the man was a Soviet spy.

But Hoover read the writeups and said, “This guy’s an alcoholic—let’s drop him.”

At that point, Angleton moved in. CIA took formal custody of Hayhannen, put him in one of its own safe houses in Manhattan, a better layout in a more secure location, and kept him available for debriefing by the lead FBI agent on the case, Larry McWilliams.

“Mac, ” as everyone called him, was stout, sharp-eyed, and streetwise, his nasal Queens dialect rich in profanity and in words like “discombooberated” or “psychophants, ” which he made up as he went along. For all his tough exterior, Mac was a thoughtful man, educated at the University of Idaho, and he was fascinated by CI; he wasn’t out talking to some tenth-grade hood, but was dealing with abstractions. He couldn’t ask, How am I going to handle a Soviet? without wondering, Now, what’s this organization behind him? How do they plan? Those were the questions that made McWilliams lay up nights, thinking. He kept a pad and pencil next to the bed, in case he had an idea about a case. And since May 12, when he had drawn the straw to go get Hayhannen at Idlewild Airport, he had been doing a lot of scribbling. He sensed they were on to something really big, and eventually Hoover did, too. After seeing the “take” from Hayhannen’s weeks of interrogation in the CIA safehouse, the FBI director happily reclaimed the case as it turned into a hunt for Hayhannen’s American controller, the mysterious Mark.

As a “cutout” between Mark and the presumably large ring of agents he controlled, Hayhannen’s basic task had been to pick up and deliver packages containing money or microfilm. One drop was the Symphony Theater, a movie house at Broadway and 95th Street, on the right side of the balcony, second row from the rear. Mark liked this location, Hayhannen told McWilliams, because two people meeting there could leave by different exits. Another spot was in Riverside Park at 96th Street, where a hole in the railroad fence could hide magnetic containers. Hayhannen had seldom seen Mark himself, but Mark had once taken him to an art studio he kept in Brooklyn. The Finn couldn’t remember where it was, exactly, but he was able to give basic directions and a good description.

After a frantic few days, Mac’s crew was sure that Mark’s place could only be in the Ovington Building, on Fulton Street in Brooklyn Heights, which rented out studios to writers and artists. It was determined that Mark had occupied number 505, directly under the author Norman Mailer. FBI agents were dispersed at sentinel points all around the Ovington—on benches in a park across from the building entrances, in an adjacent post office, and some just walking around like locals. A command post was set up on the roof and upper floors of the highest building in the neighborhood, the Hotel Touraine, two blocks down Fulton, where agents watched through binoculars. The watch went on for weeks, without result, until, at 10:45 P.m. on May 23, someone returned to Studio 505.

He was middle-aged, bald, with glasses and a fringe of gray hair. He diddled around, then put on a dark straw summer hat with a bright-white band, and came out the front entrance with a coat over his arm. A pack of surveillance pursued him to the subway stop at Borough Hall. Special agent Joseph C. MacDonald followed him into an elevator down to the tracks, and into a subway car. Both men got off at the City Hall station, in Manhattan. MacDonald tailed the man in the straw hat to 28th Street and Fifth Avenue, where he vanished.

But the watch was kept at the Brooklyn studio, where, three weeks later, on June 13, the man again appeared. Again he was tracked into Manhattan, and this time a number of agents were already waiting around 28th and Fifth; they saw him enter the Hotel Latham. A check at the front desk revealed that he was registered as Martin Collins.

Though McWilliams was convinced that the man was an illegal, the Bureau still had no admissible evidence that he was an espionage agent. But if they held off from arresting him, there was the chance he might slip away. Mac consulted Papich, who got Immigration to approve the man’s arrest on suspicion of being in the country illegally. At seven o’clock on the morning of June 21, the occupant of Room 839 at the Hotel Latham heard a knock on the door and someone saying, “FBI.”

He opened the door a crack. The G-men pushed it open and entered as a naked, groggy man stood there, blinking. They let him put in his false teeth and pull on yesterday’s clothes, and then he was handcuffed. They tried to ask him questions, but he would not talk. He gave his name as “Rudolf Ivanovich Abel, ” but would say no more.

Mac’s boys searched the room, but didn’t find much except, in the wastepaper basket, a piece of two-by-four. Just a block of wood. No one could figure out what it was, but it had to have some significance; you didn’t just find pieces of two-by-four in Manhattan hotels. Finally, one of the agents got disgusted and threw it against the wall. It split open. Inside was a cavity containing microfilm.

Developed at the FBI’s laboratory, the film was found to contain a brief message in code. The message itself was not particularly illuminating, because it referred to purported spies only by first names, but this and other clues among Abel’s effects—cipher books, locations of dead drops—corroborated the essence of Hayhannen’s story. Rudolf Abel, the FBI was sure, was an illegal who handled not just Hayhannen, but a whole ring of Soviet spies. Of course, there was still much they didn’t know about all the agents Abel had handled, especially since Abel himself refused to talk. Aside from Hayhannen, all McWilliams knew was that Abel had a lot of contact with certain Upper West Siders named Silverman, Levine, Dinnerstein, Schwartz, Fink, Feifer, Ginzburg, etc., who all seemed to be of the same background and outlook: young, well-educated, Jewish, ambitious participants in the intellectual life around Columbia University, politically involved, signers of petitions to ban the bomb, active in the Democratic Party. Later, the Bureau was able to identify a couple who were Soviet agents, Helen and Peter Kroger, whose drops Abel had serviced. But for the moment, Hayhannen’s word and the evidence in Abel’s apartment were enough to have Abel indicted for conspiring to betray secrets on “the disposition of this country’s armed forces and its atomic energy program.” After a trial that received considerable publicity, at which Hayhannen was the chief witness against him, Abel was convicted on all counts. He was sentenced to life imprisonment, and passed time in an Atlanta jail by doing calculus problems on the walls. Hayhannen was returned to his home in Peekskill, where, after a few years of freedom, he drank himself to death.

McWilliams and the FBI came out of it somewhat better. Mac got to meet Hoover, and was marked as someone who might rise. As a result of national headlines about FBI capture of the “Top Red Spy in America, ” more people started to hear about the Bureau’s work in counterintelligence, and young G-men started to gravitate toward it. And the new body of knowledge about Soviet illegal networks became the basis of a two-week FBI counterespionage course at Quantico. The course was nothing like what Papich and McWilliams and others in the FBI’s “CI Club” believed it should be, but it was a start, and there was no question but that the Abel case had enlarged their knowledge of what was going on. “The Abel case was the watershed for all of us, ” McWilliams said, “because up until then, I don’t think anybody, including CIA, really knew the deep, penetrating M.O. of the Soviet intelligence. We started to wake up and find out what the hell was really going on. And when that thing broke, my God, we were inundated with interest from the Canadians, the Australians, the French— everybody wanted to know what we knew. There was just a convulsion of activity.”

Papich always credited Angleton. “The Rudolf Abel case was a great example of cooperation, ” Papich said. “And it was one of Jim’s great accomplishments. If not for him, the whole thing would have gone down the drain. It was his influence that led to the decision to bring Hayhannen from France to the U.S.A. If Angleton hadn’t taken that position—well, I think maybe Hayhannen might have defected to the French. I don’t know what he would have done. He was a nut! Maybe nobody would have accepted him.”

But even if born of teamwork, the Abel-Hayhannen case would also lead to infighting. Having learned from Hayhannen that when illegal agents wished to meet their principals they wrote to a particular address in the Soviet Union, the Bureau’s CI men reasoned that if they could intercept communications directed to that particular address, they might net a good number of spies. In January 1958, Hoover therefore gave permission “to institute confidential inquiries with appropriate Post Office officials to determine the feasibility of covering outgoing correspondence from the U.S. to the U.S.S.R., looking toward picking up a communication dispatched to the aforementioned address.” But when the FBI’s New York SAC inquired about the possibility, Chief Postal Inspector David Stephens told him he could not authorize Post Office cooperation because “something had happened in Washington on a similar matter.” Hoover was on the verge of discovering that CIA was already opening mail in New York, but had been hiding that fact from the FBI.

LIKE WIRETAPPING and surreptitious entry, mail-opening had been practiced by Allied intelligence during World War II, and like those activities it was carried over into the Cold War. The operation had been run jointly by Harvey’s Staff C (under the cryptonym “HT/LINGUAL”) and Edwards’ Office of Security until it was officially transferred to Angleton’s reorganized CI Staff for “rations and quarters” in 1955. Angleton thought HT/LINGUAL “probably the most important overview that counterintelligence had.” Precisely because the enemy regarded America’s mails as inviolate, mail coverage was likely to provide clues to the identities of Soviet agents.

Angleton understood that the mail-opening operation was illegal, and that if it were ever exposed, “serious public reaction in the United States would probably occur.” The Fourth Amendment to the Constitution stated pretty clearly that “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, and papers and effects against unreasonable searches and seizures shall not be violated, and no warrant shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched and the persons or things to be seized.” But Angleton could rationalize mailopening on several counts. The Fourth Amendment applied only to unreasonable searches and seizures, which left it open as to whether reading suspected Soviet spies’ mail to Moscow was reasonable. Since 1947, every president and every attorney general had agreed that warrantless wiretaps could sometimes be reasonable, and if there was an exception to the Fourth Amendment for trespass via electronic surveillance, it did not take much imagination to extend that to trespass via surreptitious entry, or mail-opening. Every law had its exceptions; the laws of God and man clearly said it was wrong to kill or steal, and those laws did not say “except in the time of war, ” but everyone knew that a wartime exception was read into them. Angleton believed that any restrictions on government mail-opening must similarly have read into them an exception that would allow CIA to cover mail in time of secret war. Abraham Lincoln had authorized the Pinkerton Detective Service to open mail to catch Confederate spies; why could the country not do the same to identify Nazi or communist agents? As no less a founding father than Thomas Jefferson had once observed: “A strict observance of the written law is doubtless one of the highest duties of a good citizen, but it is not the highest. The laws of necessity, of self-preservation, are of higher obligation. To lose our country by a scrupulous adherence to the written law, would be to lose law itself, with life, liberty, and property, and all those who are enjoying them with us; thus sacrificing the end to the means.”[he is on to something there DC]

Besides, it was not as if CIA were going into every person’s mailbox. The program was carefully controlled, the targeting highly selective, the watch-listing terms tighter than those Attorney General Tom Clark had used when getting authorization for telephone taps from President Truman. The entire intent and motivation of the program involved the question of foreign entanglements, counterintelligence objects. A real effort was made to avoid harming the innocent, and there was a consensus among those who knew of the operation that nobody except Soviet spies was disadvantaged by having the CIA read his mail.

Of course, nobody ever knew his mail was being opened, either, because it was carefully done by trained personnel of the Technical Services Division within CIA. The envelopes were collected within a restricted secure area of Federal Building No. 111 (Jamaica Airmail Facility), adjoining Idlewild Airport, and couriered to CIA’s New York City office. Each evening, a six-man team of CIA technicians, fluent in Russian and proficient in holographs and flaps, would photograph envelope exteriors with a Diebold camera, and select some for opening. Perhaps two-thirds were chosen at random; the others were culled from a “watch list” which included, at various times, people like Linus Pauling, Bella Abzug, Senator Hubert Humphrey, John Steinbeck, Edward Albee, Thomas Merton, Jay Rockefeller, Martin Luther King, and Richard Nixon. The method of opening which had been taught to the CIA officers during their one-week Technical Services Division “flaps-and-seals” course was to hold the envelope over a steaming teakettle to soften the sealant, then slip a narrow stick under the flap. When you got good at it, it could be done in as little as five seconds. After the letters were photographed, they were replaced in the envelopes, were resealed and returned to the mails the following morning. CIA’s inspector general, Lyman Kirkpatrick, came by to see the new operation after it was set up and wrote approvingly: “This is a highly efficient way to get the job done and the investigators enjoy the work and appreciate the opportunity to earn overtime pay.”

It was understood by all at the Agency who knew about the program, however, that J. Edgar Hoover would be somewhat less happy about its existence. In early 1952, when the operation began, there had been some bad blood between Hoover and the chief of the Postal Inspection Service; also, CIA and FBI had been barely talking to each other. The habit of secrecy persisted even as relations improved under Papich, partly because any “confession” would have to account for why the Agency had failed to consult the Bureau in the first place. Angleton well knew that, in addition to foreign intelligence, the program would produce “information affecting Internal Security, ” and when he proposed to Dulles that his new CI Staff disseminate HT/LINGUAL information “to other Agency components, ” security chief Sheffield Edwards had therefore added by hand on Angleton’s proposal:“and to the FBI.” But Edwards’ writing it did not make it so. Angleton later explained that he held back because no matter how well he got on personally with Papich, “relations with the FBI were pretty spotty.”

In January 1958, Postal Inspector Stephens informed Angleton that the Bureau desired to begin its own mail coverage in New York. Angleton consulted Dulles, and they agreed that there was no choice but to disclose the program to Hoover before the FBI uncovered it anyway. On January 21, Angleton met with Sam Papich “on a personal basis”—late that night, among the orchids in his greenhouse, after they had been doing some drinking— and told him that CIA was opening mail. The project was one of the largest and most sensitive of all CIA covert operations, Angleton said, and its sole purpose was a foreign one—to identify persons behind the Iron Curtain who had family relations in the U.S. That was hardly the only objective of HT/LINGUAL, however, and when Hoover heard about it, he made it clear he considered the project a serious violation of turf. Papich anticipated, as he later said, that “all hell was going to break loose.”

But Hoover’s blood went from boiling to merely simmering when Papich convinced him, via assistant director Al Belmont, that CIA had some jurisdictional right to conduct mail coverage—and that the situation was actually a potential windfall for the FBI. Instead of having to start its own coverage from scratch, it could enjoy the benefits of CIA’s operation, without any of the expenses or responsibilities. “The question immediately arises as to whether CIA in effecting this coverage in New York has invaded our jurisdiction, ” Belmont wrote Hoover. “In this regard, it is believed that they have a legitimate right in the objectives for which the coverage was set up, namely, the development of contacts and sources of information behind the Iron Curtain…. At the same time, there is an internal security objective here in which, because of our responsibilities, we have a definite interest, namely, the identification of illegal agents who may be in the United States. While recognizing this interest, it is not believed that the Bureau should assume this coverage because of the inherent dangers in the sensitive nature of it, its complexity, size, and expense. It is believed that we can capitalize on this coverage by pointing out to CIA our internal security objectives and holding them responsible to share their coverage with us.”

Hoover marked the memo: “O.K.” Two days later, on January 24, Papich was sent to CIA headquarters to “point out” Hoover’s position to Angleton, Edwards, and John Maury, head of the Agency’s Soviet Russia Division.

Without mentioning Angleton’s “personal” admission to him, Papich announced that he had reason to believe CIA was opening mail in New York. CIA’s representatives acknowledged it, gave Papich a briefing, and offered to “handle leads” for the Bureau. The FBI would be the only other agency to receive raw copies of the material. In return, the FBI must restrict HT/LINGUAL materials to special-agent supervisors, who regularly handled sensitive information. FBI field offices would receive the product only after it had been sanitized. Films must never be placed in case files, though files could contain coded cross-references to allow retrieval.

Hoover agreed to CIA’s terms, and the FBI was made part of the operation, which became known in the Bureau as Hunter Project. As the joint enterprise became part of Papich’s liaison routine, he would pick up a batch of Hunter reports at the Agency each week and take them to a special desk in the Soviet Section at the FBI’s Domestic Intelligence Division. Over the following fifteen years, Papich would personally carry in his briefcase over fifty seven thousand Hunter reports from CIA to FBI headquarters. An internal Agency study would eventually acknowledge that since the Bureau received more dissemination's than any single branch of the Agency, “the FBI is receiving the major benefit from this project.” The Hunter reports included such items as indications that someone might be serving as a Soviet courier, news about Russian social and art clubs in the U.S., and contacts between American citizens and Soviet agents. The Bureau found CIA’s Hunter reports helpful in evaluating what they already had on some suspects, and closed a few cases as a result of that supportive information.

So it was with the man whom Dulles thought CIA’s best intelligence officer of all, a dry-fly fisherman who much resembled Buchan’s Bullivant. For the twenty years following December 20, 1954, he would be the FBI’s main point of liaison. His separate peace with Papich would help break a network of Soviet agents in New York, lead the two agencies into a joint project to open the mail of U.S. citizens, and limit fallout when the FBI’s prize spy prisoner was swapped for a CIA pilot downed in Russia. Yet he would also bring to the Agency a way of thinking that crystallized FBI-CIA differences, and which would ultimately rip relations apart.

BY SUMMER 1954, a whole slew of traumas and setbacks had demonstrated the need for a revamped national counterintelligence effort. The Bentley, Hiss, Fuchs, and Rosenberg cases had destroyed the country’s early naivete. The Burgess-Maclean affair alerted the intelligence establishment that its secrets could go, even if its own operations weren’t penetrated. The McCarthyism period brought home the need to prevent such morale sapping episodes by prophylactic measures. That need was felt particularly acutely by Houston, Edwards, and others concerned with personnel security at CIA, who had tangled with the FBI over Offie and Meyer and various loyalty cases, and who didn’t feel the Agency was getting proper investigative help from the Bureau. It was not so much a lack of help, as the wrong kind. CIA was all for getting tips from Hoover, but wanted to handle its own security problems internally, without the Bureau or HUAC or anyone else sneezing into the soup.

A start at reform had been made in June, when Dulles and Hoover worked out, via Houston and Attorney General William P. Rogers, a procedure for FBI investigation of “irregularities” involving CIA employees. Misconduct of any kind was to be the province of CIA’s Office of Security, which had to jump into a situation immediately—not only to preserve CIA’s public reputation, but to protect secrets which might be compromised by the curiosity of the FBI. Every so often, some CIA officer would fall afoul of the administrative charter, or, on rare occasions, flee an automobile accident, or leave a satchel full of classified documents in a taxicab, and Papich would turn the case over to Sheffield Edwards. One CIA officer had to resign after the FBI discovered that his house was stacked to the ceiling with secret government papers; he wasn’t passing them out to the enemy, just building up a library for himself, for writing books, and apparently it helped him, because he later became a top expert in foreign policy. The Bureau could have recommended that the man be prosecuted for unlawful possession of government documents, but CIA’s policy was to handle and resolve everything internally, fearing that secrets would be lost through the “discovery” process in a trial, and the FBI went along.

But DCI Dulles knew that counterintelligence involved more than just letting the Agency take care of its own; it mattered what kind of care was taken. There was a demonstrable need to be more cautious, more concerned with the principles of compartmentalization and “need to know.” If Dulles’ people were going to succeed, the security of sources, operations, and personnel was everything. That was the lesson taught by Wisner’s OPC, at least in the view of William Harvey’s counterintelligence people. If Cord Meyer was trying to suborn the editor of a newspaper, or Wisner to work with a guerrilla leader in the mountains, it was crucial to know whether one’s agent might be an informant for the security service. But OPC wanted only action. As one of Harvey’s colleagues was admonished, “Goddamn it, we don’t want counterintelligence, we want guerrillas!” Because of progress in radio detection, and because the adversary controlled Trust-style opposition groups, the task of infiltrating commandos was more difficult than it had been even ten years earlier—yet there didn’t seem to be any shift in tactics from world war to Cold War. Wisner’s men were still fighting the Nazis, still dropping people behind the lines, and it took the spectacular failures of OPC’s covert actions, in Poland, Albania, and the Ukraine, to teach the wisdom of Harvey’s more cautious approach.

Additional pressures came from outside the Agency. The White House was getting mail urging that Hoover be made director of CIA, or that the Agency be folded into the FBI; J. Edgar would kick out the commies as he had chased down Dillinger, and only then would the nation’s secrets be safe. One concerned citizen complained that CIA had been puffed into existence by Donovan’s press campaign, and that Hoover’s more efficient SIS had been taken over by the Agency because Hoover refused to publicize the FBI’s successes; “the public and even Congress never even heard of [SIS], nor did it get any publicity, nor did J. Edgar Hoover or the men in charge get pictures in the paper entitled ‘Superspy.’ ” Eisenhower responded to the pressure as any politician would, by appointing a committee to look into it. The inquiry was headed by Lieutenant General James Doolittle, and the sixty-nine-page Doolittle Report, presented to Eisenhower in September 1954, proposed some radical reforms.

Most signally, the report urged CIA to assume the country’s leading counterintelligence role. The National Security Council had given the job of collating counterintelligence to CIA in December 1947, but there was a consensus, Harvey’s Staff C notwithstanding, that countering enemy intelligence was the FBI’s job. That would have to change. The United States needed to abandon the law-enforcement route for a “more ruthless” approach, the Doolittle Report stressed, and that new ruthlessness must be applied to “intensification of CIA’s counterintelligence efforts to prevent or detect and eliminate penetrations.” The situation required a new strategy, a new concept for American life, one which would spill across normally restricted areas, legal channels, and departmental lines.

It also required a new chief of counterintelligence, for in mid-1953 Harvey had been made Chief of Base in Berlin. The outgoing Bedell Smith had told Papich early that year that Harvey was probably going to be posted abroad. “As you know, ” Hoover was reminded in a summary of that conversation, “[Harvey] has been the center of many controversies.” But there was more to the decision than a desire to keep Harvey out of Hoover’s way. Harvey himself had wanted to leave Staff C, because he hoped to rise in the Agency and, compared with other disciplines, counterintelligence was considered career ending. Harvey didn’t have much of a chance to manage people, the way he would if he were running agents in even the smallest foreign station, and thus wasn’t as easily marked for promotion; already, while he was stalled in Staff C, two less knowledgeable men with overseas experience had overtaken him. He added an extra martini at lunch, and when the chief ship of Berlin Base came free, he asked for the job and got it. Divided into Russian, British, French, and American zones, isolated in the heartland of communist Germany, Berlin was the hotbed of the Cold War. It was, too, a welcome reprieve from the hassles and obstructionism of the FBI. It would be almost nine years before Harvey worked again in Washington, though, as he would find, that was not long enough to outrun Hoover’s memory.

SAM PAPICH MET CIA’s new counterintelligence chief in a large corner office of L Building, where a row of windows looked out on the Lincoln Memorial—or would have, if Venetian blinds had not been shut against the light. Six secretaries in the anteroom testified to the new appointee’s power, as did the long row of black safes in his inner sanctum, and the piles of documents. Red priority stickers were everywhere in the mass of papers, like poppies pushing through a field of snow. In all other respects, the office lacked distinctiveness, typical CIA; there wasn’t much on the walls. But in a high leather-backed chair behind the desk was as singular a man as Papich had ever seen.

James Jesus Angleton was one of only a handful of people—Harvey was another—who would ever become truly legendary within the faceless bureaucracy of knowledge that was CIA. A chain-smoking poetry enthusiast, ace fly-fisherman, and grower of rare orchids, Angleton had been recruited into OSS after graduating from Yale. He had served under Norman Pearson in X-2 and had been particularly adept at burning and turning Nazi stay-behinds in Italy. After the war, he had been put in charge of a so-called Special Desk to handle such tasks as liaison with the Israelis and the British. That latter experience had stamped him with a general auspiciousness, for he had lunched regularly with Kim Philby and detected nothing until it was too late. Some of his Special Desk duties had also caused Angleton to clash with DeLoach the few times they met, so Papich was not entirely surprised that when he first encountered Angleton, in that corner office of L Building, they got into “a real fight.”

After preliminary greetings, the new counterintelligence chief lit a cigarette, leaned across his desk, and, in his gravelly burr, brought up a case that had allegedly been mishandled by the Bureau. It had been damaging to CIA, and Angleton made a big deal about it —maybe with good reason, but Papich disagreed with him. It got to a bitter stage; they were shouting insults. Finally, Papich just walked out. Maybe Angleton was testing him, to make clear that he was going to dominate liaison. Well, thought Papich, he’s not going to.

They saw each other again the next day, and managed to act cordially. Before too long, small talk brought out that they were from neighboring big-sky states, and they both liked fly-fishing. They went off one weekend to do a little angling for brown trout in the freestone streams of West Virginia, and after that they were friends. Papich was impressed by the fact that Angleton would never just cast a fly; he would always spend a half-hour or so just stalking along the riverbank, examining the insect life, and then craft lures to imitate the species along that particular stretch of shore—brown ants, inchworms, soldier beetles, whatever he saw. Angleton had mastered the esoteric lore and literature of the discipline, which dated back to fifteenth-century Scotland; he could loop his line through the air and splash it onto the waters just so, in imitation of a hatching fly, and his vest and hat were decorated with traditional fly designs, in all their exotic colors and types and names: Flamingo Zonker, Yellow Goofus Bug, Egg-Sucking Leach. Angleton knew them all, but his standby was the Gray Ghost, a classic American freestone-river design—ocher floss-silk body ribbed with flat silver tinsel, black silk nose, white buck tail, and gray cock hackles sweeping sleekly back, like wings. Given Angleton’s own spookish demeanor and suspicious outlook, “Gray Ghost” became one of his nicknames, and colleagues thought it the one that fit him best.

The fishing trips sealed what would become a close working relationship, and Papich became a serious student of Angleton’s counterintelligence philosophy. To Angleton, catching spies was much like landing trout. It was all about patience, research, deception. Yet CI was not merely a body of knowledge; it was also a way of seeing things. It meant transcending the details of a case, putting tactical problems in a strategic perspective, gaining a larger view. Angleton felt that too much of the country’s conception of CI, as promoted by detective entertainments and the FBI’s own actions, was “spy versus spy.” That was like fighting soldier-to-soldier using bayonets, as opposed to understanding why the soldiers were being put face to face. That was counterespionage, not counterintelligence. What CI really required, most of all, was a good dollop of focused historical research—not the random digestion of massive mounds of fact, but purposeful, teleological analysis, looking for patterns over a long period of time. His work against the Nazis had taught him that patient accumulation of fact allowed one to decipher the enemy’s thinking, and thus anticipate his moves. If one could not read the enemy’s files, one could at least read his mind.

Trying to read the Soviet mind on CIA-FBI relations, Angleton considered it logical that the KGB would try to split America’s CI community along its pre-existent fault line. “When the enemy is united, divide him”—so the ancient Chinese strategist Sun Tzu had counseled in The Art of War—a work which, through the Mongol-Tartars, had greatly influenced Russian strategy, and which, in English translation, Angleton had read more than once. “Drive a wedge … Separate the enemy’s allies from him. Make them mutually suspicious so that they drift apart. Then you can plot against them.” The West itself was trying to split Romania and Hungary from Moscow, and to play Soviet military intelligence (the GRU) against the KGB. Just so, Angleton reasoned, the Soviets wanted to sow schisms between the Americans and the British, and between CIA and FBI. “That was part and parcel of Jim’s basic philosophy—he didn’t want that to happen, ” Papich would later say. “It was one of the worst things that could happen, because once you destroy a relationship between services, you’ve destroyed the effectiveness of both services.”

Though the CI chief was not yet sure exactly how the Soviets would make inter-agency trouble, he guessed they would try to capitalize on a “dissociation of sensibility.” (The phrase came from a famous essay by Angleton’s favorite poet, T. S. Eliot, who used it to describe thematic dualism's in literature; Angleton used it to describe the tension between Hoover’s law-enforcement mentality and CIA’s double-agent approach.) Angleton also supposed the KGB would try to slip between jurisdictional cracks. Just as a fly-fisherman, spotting a brown trout nibbling near the surface of the shallows, would cast from beyond its field of vision, so would the Soviets profit from inter-agency blind spots. If such schemes were not thwarted by close liaison, American CI would be essentially at war with itself, and the game could be lost. “Counter-intelligence, ” Angleton liked to say, “is only as good as relations between the CIA and FBI.”

AN EARLY TEST of the new cooperation came when Papich tried to broker a joint FBI-CIA operation to kidnap a Soviet spy in the Middle East. Elizabeth Bentley had told Harvey back in 1946 that her controller, an American known to her only as “Jack, ” had been operating a big net of agents; by 1953, FBI counterintelligence man Robert Lamphere was sure that “Jack” was an American man named Joseph Katz. Subpoenaed by HUAC, Katz had fled to Israel, where, being of the Jewish faith, he was automatically eligible for citizenship. The U.S. did not have an extradition treaty with Israel, but Angleton’s close ties to Israeli intelligence offered certain possibilities. Lamphere had met Angleton back when he was running Special Desk, and though they had little direct contact, Lamphere had always got excellent results whenever he asked, via liaison, for Angleton to do something overseas. Now the three formulated a joint FBI-CIA operation to return Katz to the United States. The key to the operation would be luring Katz onto a U.S.-registered boat, outside Israel’s territorial waters, where Lamphere could make a legal arrest. It was going to be risky, but Lamphere outlined the plan in a memo to Hoover, who gave preliminary approval. “He didn’t like the idea of the joint CIA-FBI operation, ” Lamphere said, “but had been made to understand that the FBI did not have the resources or contacts in Israel to pull off this one, whereas the CIA did.”

Papich and Lamphere got all their shots, and were ready to fly to Israel, when Hoover took a last-hour look at the whole operation and scotched it. The FBI director told them that he’d talked to a deputy attorney general, and had got the distinct impression that Angleton had informed Justice of the plan. Feeling that this was supposed to be an FBI expedition, and that CIA had overstepped its jurisdiction by going to Justice, Hoover called the whole thing off. Angleton insisted that he’d never had any such conversation with Justice, and Lamphere told Hoover that Justice probably knew about it because he, Lamphere, had cut them a copy of the planning memo, but there was no moving the director.

Of course, the team was extremely disappointed. “I was chagrined on two counts, ” Lamphere remembered. “One, both Sam Papich and I had wanted this joint operation to improve relations between the FBI and the CIA—and the result had been just the opposite, a further rupture between the agencies. Two, I was disappointed that my one best hope to reopen the Bentley case and prosecute some of the key figures was now gone.” Lamphere was so disgusted with Hoover’s bullheadedness that he soon resigned from the Bureau.

Angleton also was peeved. He went to Papich and said, “Why the hell did the boss turn this one down?” Papich thought the director was probably concerned that another agency—and another foreign service, the Mossad—had too much operational control. He recounted how some botched operations with local police in the hunt for Dillinger had taught Hoover to participate in joint projects only if he could control the show. That didn’t wash too well with Angleton. It sickened him that, despite the best laid plans of FBI and CIA men, Soviet spies like Katz still could count on the “dissociation” of American counterintelligence.

RUNNING OPERATIONS SILENTLY, without Hoover’s direct knowledge, produced much better results. In one case, Angleton got the Bureau access to a New York mob lawyer. The man was a rascal, but there was no counting the cases the FBI prosecuted on the basis of his cooperation, all involving corruption within unions and city government—and all for free, just given over by Angleton. Papich also worked with CIA people on projects spearheaded by Angleton in the cryptographic field, while the Agency, for its part, serviced countless FBI requests for coverage of American communist leaders traveling abroad. Since the great majority of Soviet and Eastern-bloc operations against the U.S. were originated overseas, CIA was naturally able to supply more leads for the FBI than conversely, but the Agency got its share of dividends. Angleton would ask the Bureau to undertake “black bag” jobs against certain domestic targets, and the Bureau would sometimes do so.

But good relations at the working level were always constrained by tensions at the top. Angleton’s own relations with Hoover were cordial the few times they met, but looking back a quarter-century later, the CI chief would realize that during all those years, from the 1950s through the mid-1970s, “there weren’t more than three or four meetings” between Hoover and the directors of CIA, except where they bumped into one another at a national security conference. There was no question in Angleton’s mind but that this adversely affected CI. On the other hand, Angleton had to admit that Hoover had some good reasons to be wary of CIA. In October 1955, for instance, Papich carried over a letter from Hoover suggesting that Donald Maclean might have compromised CIA employees. Maclean had been “a frequent visitor” at CIA, according to a Bureau source, and was alleged to have “dated two of your stenographers.” An FBI search of logs kept by the door guards at CIA’s “O” Building, in front of the Lincoln Pool, showed that Maclean often entered that particular building after hours. While there was no firm proof that he had dated any CIA women, such episodes did not increase Hoover’s trust of CIA.

Hoover’s sometimes petty power plays were none too helpful, either. FBI man William Sullivan later alleged that the FBI planted stories critical of the CIA, and it appears that, in September 1955, the FBI director went public with the accusations against Philby in a way that embarrassed the Agency. Columnist Walter Winchell, a Hoover friend, reported on his popular Sunday-night radio show that Burgess and Maclean had escaped to Moscow after being tipped off by “another top British intelligence agent” who had been in Washington; Winchell said that “the FBI refused to give this man any information for over three years, ” which was false, but that “other American intelligence departments opened up their very secret files for him, ” which of course was true. Hoover also tried to sour the opinion of Joseph Kennedy about CIA in February 1956, when the Boston power-broker was named a member of the president’s Board of Consultants on Foreign Intelligence Activities. “I discussed with Mr. Kennedy generally some of the weaknesses which we have observed in the operations of CIA, ” Hoover told his top deputies after a private meeting in his headquarters office, “particularly as to the organizational-set-up and the compartmentalization that exists within that agency.” Nor would Hoover keep out of the Washington paper-mill Attorney General Rogers’July 28, 1958, statement that “he [Rogers] just wished the FBI was doing the intelligence work abroad instead of CIA.”

WITH THAT KIND OF SENTIMENT radiating down, it was unsurprising that the two agencies were unable to agree in some important areas, including the storage and retrieval of secrets. The issue arose because Angleton, shortly after becoming Chief/CI, started computerizing document on the huge vacuum-tube punch-card monsters then being made by IBM. With IBM’s help, he developed an innovative computerized microfilm file-index known as Walnut; the project began with Abwehr documents captured in World War II and spread from there. In 1955, Angleton persuaded Dulles to create a U.S. Intelligence Board Committee on Documentation (CODIB) to promote community-wide computerization, but the FBI was not interested in applying computers to its name-trace or identification work. “We’ve got three warehouses, full of papers, and files, and thousands of people, who can run around and work the files, ” Hoover’s CODIB man insisted. Nor did CODIB ever achieve inter-agency standards to ease the exchange of data; CIA and FBI couldn’t even agree on the order of “header” items in a biographic record. “Do you want last name first, then first name and middle initial, followed by date of birth, followed by place of birth?” That question was debated for eight years, and it was not surprising to those within bureaucratic Washington, let alone familiar with FBI-CIA difficulties, that during the entire existence of CODIB, from 1955 to 1963, so simple a problem was never resolved.

While CODIB stalled over minutiae, a deeper problem for centralized analysis stemmed from the FBI’s anti analytical bias. Rocca built an extensive research section, but the FBI’s, headed by Bill Sullivan, was comparatively small, and was directed mostly at the CPUSA, not the KGB. That always rankled Papich. “If, over a period of five years, X number of Soviets had visited New Mexico near Los Alamos, and had been seen driving around—well, who were they, what were their backgrounds? Could the Bureau draw any conclusion as to what the target was? What the hell did it all mean? We’d zero in on an individual, primarily to develop evidence for prosecution, but we did very little big-picture thinking. That all goes back to our law-enforcement nature.”

But if the Bureau was little interested in CIA’s historical research, Angleton’s CI shop, for its part, benefited greatly from FBI tips on the way the Soviets worked. For the first two years of Angleton’s tenure, the Bureau couldn’t tell CIA much it didn’t know already, but that began to change in 1957, when the Yale choir made its maiden trip to Moscow, and the Soviets began opening up, a little bit, to the world. After that, CIA had a lot to learn from the Bureau’s debriefings of returning American tourists. The real epiphany was to come that same year, when Angleton’s cooperation gave the Bureau its biggest break so far in the secret war against Soviet spies. Even so, it was a cooperation that would have to be hidden from Hoover—and the FBI would repay it by risking the safety of CIA’s only mole in Moscow.

• • •

ON MAY 4, 1957, a rumpled, mustachioed, dark-haired

man entered the U.S. Embassy in Paris with liquor on his

breath. Through a thick Finnish accent, Reino Hayhannen

told the State Department’s duty officer that he had

important national security information to share with the

United States. The duty officer turned him over to the

FBI’s resident legal attache, who considered him “a

weirdo,

” took him outside and put him into a taxicab with

instructions on how to get to the CIA’s offices, telling

him,

“It’s clearly a case for the CIA.” But as soon as one

of CIA’s officers heard Hayhannen’s story, he got on the

phone to the legal attache and insisted: “This guy doesn’t

belong to us, he belongs to the FBI.” The walk-in was

passed back and forth two or three times until finally

someone in the CIA offices listened to him.Hayhannen claimed to belong to a network of spies in the New York City area, and identified himself as a Soviet “illegal.” In CI jargon, an illegal was any foreign intelligence officer dispatched to the United States under a false identity, in violation of immigration law. Although technically no spy openly declared his profession and all spying was against the law, most intelligence personnel were “legal” in the sense that they were affiliated with their home nation’s embassy and performed some nominal diplomatic functions to justify their presence in country. Illegals, by contrast, might enter the U.S. under totally fictitious identities, often taken from tombstones. They would never make open contact with their sponsors’ embassy, and could live relatively undetected, especially in a polyglot place like New York. Once past the customs barriers of his unwitting hosts, the saying went, a Soviet illegal disappeared like a diamond into an inkwell. It was assumed that illegals aimed to get employment that would permit easy access to scientific and technical information, and that they hoped to penetrate the intelligence community and perhaps even enter political life. Beyond that little was known, because the FBI had never caught a Soviet illegal, or had the chance to debrief one.