THE ULTIMATE EVIL

An Investigation into a

Dangerous Satanic Cult

By Maury Terry

An Investigation into a

Dangerous Satanic Cult

By Maury Terry

V

Countdown:

The Final Week

Stacy Moskowitz and Robert Violante were rushed by ambulance

to Coney Island Hospital and then promptly transferred

to Kings County Hospital because doctors believed their severe

head wounds could be better treated by the team of neurological

specialists there.

As word of the attack filtered rapidly through the media

grapevine, a host of television, radio and print journalists converged

on Kings County while others hastened to the Shore

Parkway shooting site. The scene at the hospital was one of

pandemonium. The News's Jimmy Breslin and later Steve

Dunleavy of the Post, both of whom were prominent in Son of

Sam reportage, joined the crush of reporters jamming the corridors

outside the emergency room.

The three television networks and their New York flagships

sent crews to Kings County, as did local TV outlets WOR,

WPIX and WNEW. The Associated Press and United Press

International dispatched representatives, who melded with reporters

from Time and Newsweek. Both national newsweeklies

had already devoted substantial space to the .44 killings, and

would do so again.

Radio reporters from more than a dozen stations also arrived,

along with staffers from the New York Times, Long

Island's Newsday, New Jersey's Bergen Record and other

newspapers. Even the European press was represented by

members of several publications' New York bureaus. [All those people reporting and not one of them investigated the case DC]

On the fringes stood the victims' families. Overwhelmed by

fear for Stacy and Robert and stunned by the sudden media

explosion, the Moskowitz's and Violante's were on the precipice

of shock and collapse. Hospital administrators recognized the precarious situation and directed the couples to a more

private area. Still, bedlam reigned.

Behind a curtain in the nearby emergency room, Stacy remained conscious, frequently calling out in pain for her

mother. Neysa ran to her daughter's side, but aides gently

escorted her from the room. "Baby, baby, you'll be O.K.," the

anguished Neysa called back over her shoulder. Stacy's right

eye was swollen shut and the lid was a morbid black and blue.

Before the doctors could operate, they first had to control

her bleeding. Dr. William Shucart, chairman of the neurosurgery department, was reached at his Westchester home by

Dr. Ahmet Oygar, chief neurosurgical resident, after he and

Dr. James Shahid conducted a preliminary examination of

Stacy. Shucart consulted briefly with his colleagues, then

dressed and drove to Kings County to direct the operating

team.

Meanwhile, Violante was wheeled into surgery. His left eye

was completely shattered, but specialist Dr. Jeffrey Freedman

hoped to save his life and, if possible, also preserve a degree of

sight in the right eye.

An agonizing deathwatch, which through the media presence would be observed by an entire nation, had now begun.

At the same time, the NYPD was engaged in a mad scramble. The Omega task force members, who could by now count

every jagged sidewalk crack in Queens and the Bronx, were

preparing to shut down for the evening when news of the

shooting arrived at the operation's headquarters at the 109th

Precinct in Queens at about 2:50 A.M.

At first Omega commander Timothy Dowd discounted the

attack as being Son of Sam's. He simply refused to believe the

murderer would thwart the dragnet and strike in Brooklyn, even though the parked-car setting was indicative of the .44- Caliber Killer's modus operandi.

But Dowd was persuaded when detectives on the scene

radioed that the bullet hole in the Skylark's steering column

was large—consistent with that of a .44 slug. Only then did

Dowd react. In total, nearly an hour elapsed before a decision

to set up roadblocks at the bridge and tunnel exits from Brooklyn was communicated to the field. An advisory regarding the

yellow Volkswagen also was transmitted, as at least two neighbors who lived near the shooting site told detectives of the

VW's flight from the top of the park.

Grim faced cops, revolvers at the ready, halted cars for

more than two hours at various bridges and tunnels: scanning

drivers' faces; trying to spot a gun on a floor or back seat;

looking for something—anything—that might indicate the

man behind the wheel was the murderer. It was all in vain.

Other detective teams had a dozen of the department's top

suspects under surveillance. And as the night wore on, the

depressing news became apparent: all were accounted for;

none were near the shooting scene. And frustration exploded.

Two detectives, parked outside a high-priority suspect's

home, heard the "shots fired" report over the Omega force's

special radio band. They'd been investigating the man for

weeks, sticking closer to him than did his wife's mother. He'd

eluded them the night of the shooting at Elephas, and they'd

caught fifty pounds of hell for it. Now they were positive he

was in his house—but they had to make sure. What if he'd

evaded them again and gone out a back window?

The cops rang the bell. No answer. Maybe he had slipped

away, gone to Brooklyn and done the shooting. The detectives

knew they'd be pounding the pavement in Staten Island. They

rang the bell again. Now there were sounds of movement inside.

Revolver drawn, one of the detectives stepped away from

the doorway. Then the door opened and the sleepy, somewhat

inebriated "suspect" stood in front of them—and the other

detective promptly punched him in the mouth. Anger and

frustration. It was the worst of all nights for Operation

Omega.

The Omega detectives were good, professional cops—among

the city's best. Many worked long, grueling hours and volunteered

even more time than that. Some suffered family and

personal crises because the case was so demanding, time-consuming

and obsessive. Personalities changed. Resentment simmered

until anger boiled over—sometimes at home, sometimes

on the job, sometimes in the smoky, beer-charged atmosphere

of a neighborhood bar in Queens.

As dawn broke on July 31, 1977, it was a sour summer

Sunday. The police were back at square one, no closer to snaring

the killer than they'd been in July 1976.

At Fire Island, we awoke at nine in the morning on July 31

and heard the news of the shooting on the radio.

"Brooklyn," I exclaimed to George over breakfast. "God- damnit, the bastard went into Brooklyn!"

"This guy is one smart son of a bitch," he replied. "You've

got to wonder if they'll ever get him now. What's that—thirteen victims? It's unreal. How much can they take over there?

The city must be going nuts."

Eyeing the kitchen clock, I hurried to meet the 10 A.M. ferry, which carried the morning newspapers.

The trip was hardly worth it. Since the attack occurred after

the newspapers' deadlines, recap stories and updates on the

task force were all that appeared. The Times, its foot firmly in

its mouth, reported that the killer's warning of an anniversary

attack had gone "unfulfilled." "PROBE FIX RING IN N.Y. COURT" was the Daily News's page one banner. The murderer had rendered the papers obsolete before they were delivered. So radio and TV became the main news sources of the

day at the beach.

Robert Violante survived his surgery; his life had been

saved. But the doctors, who knew going in that his left eye was

gone, were guarded in their prognosis for the right one, through which he could only distinguish a gray haze of light. The surgeons hoped that the faint glimmer indicated he might

regain at least a semblance of vision in the right eye; but they

weren't optimistic.

The operation Shucart and his team performed on Stacy had

at best a remote chance of success. One slug had grazed her

scalp, causing minimal damage. But a second bullet entered

the left side of her head and traversed downward through her

brain before embedding in the base of her neck. The damaged

brain portion, which influenced motor functions, was removed

in the course of an heroic, eight-hour operation. Her condition

was stabilized, but the surgeons knew the outlook was bleak. Later that night, it was reported that Stacy was returned to the

operating table.

There were no deadline problems for the newspapers on

Monday, August 1. "44-CAL KILLER SHOOTS 2 MORE, WOUNDS BKLYN COUPLE IN CAR DESPITE HEAVY

COP DRAGNET. 12TH AND 13TH VICTIMS OF SAM,"

the Daily News proclaimed. The Post, seizing on comments

from Dowd and Commissioner Michael Codd, truthfully but

sensationally shouted across page one: "NO ONE IS SAFE FROM SON OF SAM." The Times also displayed the story

prominently on its front page and continued with extensive

coverage inside.

The News picked up on the yellow VW, but only vaguely— saying merely that two witnesses reported the killer fled in

such a car.

The paper did have a gem inside, the story about Michelle

Michaels (whose real name was withheld) being followed by

the man in the yellow car as she rode her bike shortly before

the shooting. The News seemed confused, mentioning again, as

it had in its lead article, that other witnesses saw a VW flee. The first inklings of a second car were there, but the paper

didn't know what to do about them. And the police, normally

very cooperative with the press on the .44 case, weren't about

to help. Not this time. The VW chase and other important

information would be kept from the public.

The Post included a scene map in its layout, correctly showing the escape route through the park to a car waiting on the

opposite side. They'd drawn the killer's auto one block too far

to the north, but were in the right area. These points are mentioned because, when the arrest occurred ten days later, no one

carefully studied the scene or investigated inconsistencies in

the announced police version of the events of that night.

Three words can sum up the police investigation in the wake

of the Brooklyn attack: Volkswagen, Volkswagen and Volkswagen.

Out of the public eye, this was the entire focus of the probe

—along with interviews of Alan Masters, Violante, Tommy

Zaino, the Vignotti's and later Cacilia Davis in an effort to

arrive at an accurate composite sketch of the killer. It would

be a hectic and confusing week for the police, who themselves

would be shocked by the arrest of David Berkowitz on August

10.

The attack had occurred in the 10th Homicide Zone. Normally, the detectives from the 10th would have been absorbed

by the Omega force; and indirectly they were. But for the most

part, Dowd and his assistant, Captain Joseph Borrelli—with

the concurrence of the PD's top brass—allowed the 10th a free

hand while the Queens detectives began investigating new suspects from the deluge of tips that were now flooding the .44

hot-line number at the rate of a thousand busy signals per

hour.

In the aftermath of a major crime, it is routine to check

traffic tickets in the event the perpetrator happened to receive

one and because a witness might be located among those cited

at the approximate time of a given incident.

A police supervisor claims that sometime during the morning of July 31 the two sector officers, Cataneo and Logan, were

asked if they'd handed out any tickets in the vicinity of the

assault. Both had responded to the scene and to the hospital. They were drained. Allegedly, they replied they hadn't written

any summonses—when of course they had done so. The two

officers later acknowledged they had no recollection of writing

any, but have been unclear as to whether or not they were

asked if they had.

The tickets wouldn't be found until August 8. It is possible

that no one checked for summonses. It is also possible that

Cataneo forgot to submit them until later in the week. Or it

may have happened that he inadvertently left the ticket book

in the patrol car, where it was later discovered and turned in

by another officer. Whatever, it would be Mrs. Cacilia Davis

who would alert the police to the fact that summonses indeed

were written on her block shortly before the shooting.

David Berkowitz certainly knew tickets were issued—he

had one. Back in Yonkers the same day, July 31, Berkowitz calmly sat down, opened his checkbook and in a clear, steady

hand wrote check #154 from his account at the Dollar Savings Bank in the Bronx. The draft was made out in the amount

of $35, payable to "Parking Violations Bureau N.Y.C." to satisfy the hydrant infraction noted on summons #74 9069532. Berkowitz inscribed the number of the citation and that of his

license plate, 561-XLB, across the top of the check.

Berkowitz's action would seem to be an uncharacteristic one

for a so-called "mad, salivating, demon-possessed monster"— as the police would have liked the public to believe—to take

just hours after allegedly gunning down two young victims

with the clamor of infernal deities pounding in his brain.

Berkowitz mailed the summons and the check, which was

cashed on August 4 by the city of New York.

But, still on July 31, police officers and detectives from the

62nd Precinct canvassed the Bensonhurst neighborhood, jotting down the license plate numbers of some two hundred cars

in the immediate vicinity of the shooting. This was done on the

chance the killer fled on foot, leaving a car behind; or had arrived in one auto and left in another already waiting for him, with the intention of returning for the second car. The canvassing also was a way of locating potential witnesses.

In addition to logging licenses, the detectives knocked on

doors in the area. In doing so, they met several key witnesses

—including the Vignottis, Donna Brogan, Mr. and Mrs. Raymond, Mary Lyons, Paula and Robert Barnes and others. Gradually, a picture began to develop.

Also on July 31, an interesting discovery was made a few

miles east of the shooting site. A map was found in a phone

booth at a Mobil gas station at Flatbush Avenue and Avenue

U. According to a confidential police report: "The major access routes in Bensonhurst, Sheepshead Bay, Flatlands, Canarsie and Greenwood Cemetery sections of Brooklyn were

outlined in heavy, colored ink. The Bensonhurst section, which is outlined in red, has a number '1' pointing to the spot

near where the commission of this crime took place."

The other neighborhoods mentioned surrounded Bensonhurst, and the number "1" coincided with the time the

yellow VW arrived there with its two passengers.

The map's presence in a phone booth implied a telephone

call to someone; perhaps a conspirator, perhaps not. But the

police weren't looking at a conspiracy angle. And with the

avalanche of reports coming in, it is likely the potential relevance of the map was overlooked. Berkowitz, incidentally, would later admit to being within two blocks of that gas station the night of the attack.

The next day, August 1, Alan Masters came forward to

Detective Roland Cadieux and Sergeant Gerard Wilson and

told of the VW chase. He was questioned a second time by

three members of 10th Homicide—Detective Ed Zigo, Detective John Falotico and Sergeant William Gardella.

Armed with Masters' information, other detectives traced

the escape route. At Independence Avenue, the narrow, one- way block through which the cars sped in the wrong direction, they rang bells up and down the street, seeking witnesses who

might have spied the VW or its plate number. No luck.

Continuing on, they arrived at nearby Fort Hamilton, situated off the Belt Parkway on the route Masters said the VW

traveled. There, they obtained data on all VW owners with

access to the base, as well as to Fort Totten in Queens and Fort

Tilde.

The U.S. Coast Guard was then contacted as police at- tempted to learn shipping schedules along the Brooklyn and

New Jersey waterfronts on the theory the VW driver—Son of

Sam to the police—might have been a merchant seaman. If he

was a crewman, coming and going with his ship, it could have

explained the irregular lapses between .44 attacks, the authorities reasoned. Plus, the VW had indeed escaped along the waterfront.

Other reports on yellow Volkswagens were filed throughout the day, and neighborhood residents continued to advise the police as to what they had, or hadn't, seen. Tommy Zaino, who gave his first statement to Detective John Falotico on Shore Parkway forty minutes after the shots were fired, was questioned again at one-thirty that afternoon.

His description of the gunman was consistent, concise, and his recollections were vivid. He was one of the best witnesses the detectives had to work with in the .44 case. Zaino's existence, but not his last name, was leaked to the Daily News by Brooklyn police. The paper referred to him as "Tommy Z.," adding that he was parked directly in front of Violante and Stacy.

Why the police, in whispering Zaino's name to the News, didn't call him "Tommy X" is a matter to be questioned. Zaino was known in the area, and the police had no way of being sure that Son of Sam didn't write down the Corvette's license number, which, although the car was borrowed, could have led back to Zaino. In fact, on the night of August 1, only hours after "Tommy Z." appeared in the newspaper, Zaino had a close brush with death. As he closed up his auto body shop Zaino was shot at by three men who drove past the front of the building in a car he couldn't identify. Zaino was promptly placed under police protection and housed in a motel across the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge in Staten Island. And although he was now under an official umbrella, the protection wouldn't last indefinitely. After a few weeks he'd be on his own again, a potential target once more.

That wouldn't be the only time the 10th Homicide detectives played roulette with a witness. Cacilia Davis would endure the same experience a week later.

The blinded Robert Violante was himself questioned in the intensive care unit at Kings County Hospital on August 1. He described the grubby man in the park, but told police he didn't see the gunman as he pulled the trigger.

It was a busy, eventful day for the NYPD. But the police and the entire metropolitan area ground to a halt late that afternoon when the announcement came that Son of Sam's double assault in Brooklyn had now become a single assault— and a homicide. At 5:22 P.M. on August 1, some thirty-nine hours after the shooting, Stacy's heart stopped beating.

The "Deathday" anniversary may have arrived late, but it was observed.

The toll now stood at six young people dead, seven wounded.

With the announcement of Stacy's death, the lid blew off New York's already boiling pressure cooker. Several incidents of mob violence erupted, with crowds attempting to attack suspicious young men in yellow cars or bar patrons who spoke eerily or offensively to teenage girls.

In Brooklyn's Sheepshead Bay section, a group of vengeful tavern customers rushed into a street as police arrested a man who sat with two revolvers in a yellow car. Screaming and shouting, "Kill him! Kill him!" the crowd surged at the police and the suspect, whom they believed was Son of Sam. The cops quickly handcuffed the man, flung him to the floor of their patrol car, and squealed from the block.

In suburban Mt. Vernon, the cemetery incident occurred in which two young men dragged an innocent third to his father's grave and attempted to beat a confession out of him. In the Bronx and Queens, fearful residents phoned police to report sighting men dancing around the graves of two .44 victims.

Throughout the city, the situation was explosive.

It was also a time of questionable taste. Vendors began hawking T-shirts which read: "Son of Sam—Get Him Before He Gets You." Another entry, stained with splotches of red dye, contained a facsimile of several paragraphs of the Breslin letter. And a rock group released a recording called "The Ballad of the .44-Caliber Killer." Cynics said it was "number 44 with a bullet" on the charts.

Now, too, the reward money was posted. Donations from the Daily News, WABC-TV and a number of corporations and fraternal organizations rapidly reached $24,000. The total would rise steadily to $40,000 by the day of the arrest.

The case was now daily front-page news, and the nightly TV broadcasts also hammered hard at the story. In City Hall, Mayor Abe Beame was feeling intense heat. The Democratic 102 On Terror's Trail primary was barely a month away, and the city was blowing up around him and was at the core of a national media storm. He was already trailing Ed Koch in the polls, and this .44 madness, which made both him and his Police Department appear incompetent, was now out of control. Rather than wearing heroes' laurels, Beame and the police brass were accumulating funeral wreaths. Something had to be done.

Trying to grasp a greased rope, Beame announced that he was authorizing the immediate rehiring of 175 of the cops who'd been laid off in the fiscal crisis. He also ordered the strengthening of the Omega task force, and the group's ranks were increased to 300 overnight. Son of Sam had to be caught.

For a number of reasons, Tuesday, August 2, would prove to be the most pivotal day in the police investigation. As detectives continued to interview Bensonhurst residents, handle telephone tips and search for the yellow Volkswagen, Cacilia Davis met with her friends Steve and Tina Baretta* and discussed what she'd seen early Sunday morning. She explained that the previous police sketches didn't resemble the man who passed by her just before the attack. By then, Mrs. Davis realized the "long boom" and horn she'd heard were the sounds of the shots and Violante's reaction to them.

*name changed

She was frightened. She was upset. Her dog, Snowball—or Snow, as she called him—was a distinctive white spitz; the only one in the area. If the killer decided to eliminate a key witness, he'd have little trouble locating Cacilia Davis. She wanted to help, but she didn't know how to go about it and needed to talk it through with Tina and Steve.

The Barettas convinced her she'd be safer speaking to the police than remaining in a fearful silence. Mrs. Davis agreed, and Tina called 10th Homicide during the evening of August 2. She was remotely acquainted with Detective John Falotico and asked if he was in.

Falotico had been engrossed with witness Tommy Zaino and police artist William McCormack, trying to arrive at a concise sketch of Son of Sam that would join the drawings compiled from the other attacks. With interviews of Violante, Alan Masters and the Vignottis—who saw the short-haired man approach the yellow VW—already in hand, the detectives were considering it likely that the killer wore a wig.

Detective Joseph Strano, thirty-six, a strapping police vet- eran of fifteen years, advised Tina that Falotico wasn't avail- Countdown: The Final Week 103 able. Tina thought about hanging up, but decided to tell the story to Strano. Strano liked what he heard. Accompanied by Detective Jim Smith, he immediately drove to the Barettas' apartment. There, a nervous Cacilia Davis sat waiting.

After some small talk designed to allay the widow's fears, Strano began his questioning. A review of his detective division report (DD-5) reveals that Mrs. Davis told him about the ticketed Galaxie and said that she barely reached her front door before the shots were fired. The fact that she observed the Ford leave Bay 17th Street before the shooting was inconsequential to Strano, who, like the rest of the NYPD, was looking for a yellow VW.

He was much more concerned with the physical description of the man who passed Mrs. Davis on foot at 2:33 and what he appeared to be hiding up his jacket sleeve.

After writing down Mrs. Davis' detailed description of what the man on Bay 17th Street was wearing, Strano zeroed in on the object he was carrying up his sleeve. Mrs. Davis, as Stra- no's report reveals, thought it was a portable radio, but "perhaps a gun."

However, Strano then put his own .38 service revolver up his sleeve—barrel first, with the butt, or handle, facing back- ward—and Mrs. Davis remarked that yes, it did look like that. And Strano wrote the word "gun" in his report.

But was that a positive identification? Hardly. And why a weapon was supposedly carried in such a bizarre manner by an experienced shooter has never been explained. At other Son of Sam shootings, and in Brooklyn as well, the killer pulled the .44 from beneath a shirt or coat, or carried it in a bag. That was the modus operandi—why would this time be different?

It is also difficult to believe that Berkowitz would have called attention to himself by blowing his horn and following a police car if he had the infamous Bulldog in his possession.

And if the gun was under his shirt—as seen by Zaino two minutes later when the killer approached the Violante car— why would he have so brazenly, and awkwardly, displayed it two blocks away?

Because he was thinking of shooting Mrs. Davis? No. Even in his own muddled confession, Berkowitz, in becoming the man in the park, would recount spying on Stacy and Robert as they rode the swings—an action that occurred twelve minutes before Berkowitz's encounter with Mrs. Davis on the street. Berkowitz wouldn't, couldn't, confess to his presence on Bay 17th just prior to the shooting. He had to become the man in the park—the killer—in order for his confession to have the slightest chance of being accepted. He would say he was sitting in the park, watching Stacy and Robert with the gun in his jacket pocket.

So if he wasn't carrying a gun on Bay 17th, what was the object hidden in his rolled-down sleeve? It might have been the flashlight that would be found in his car the next week. A flashlight could have been used to blink an "all clear" signal to the man in the park. Or it might have been the hand-held police scanner which would be found in his apartment. Or it might have been a portable walkie-talkie, although none would be found. In any case, it is highly doubtful he was carrying a gun. And it appears reasonable to suggest that Mrs. Davis, who originally thought the object was a radio, was swayed by Strano's demonstration.

Back at 10th Homicide, Strano filed his report. The detectives in Falotico's camp, who were familiar with Zaino's description of the actual killer, his clothing and that of the VW driver, thought Strano's witness was off the wall. And when Mrs. Davis' comments about the tickets were discussed, several police were further convinced she was in error. There weren't any tickets.

Strano spoke to his witness again. She remained adamant: tickets were indeed written. The police didn't believe her. Mrs. Davis threatened to contact the media anonymously and tell reporters the police refused to search for the summonses.

She was frightened, and angry. She'd come forward, and now most at 10th Homicide were ridiculing her. But not Strano. This was his witness, his big break. With the approval of his supervisor, Sergeant James Shea, the detective returned to Cacilia's apartment the next day—Wednesday, August 3— with police artist Bill McCormack. There they began to work on a profile sketch.

Later, Strano and Mrs. Davis took the first of several shop- ping trips in Brooklyn, trying to locate a denim jacket identical to the one the man wore. It was fruitless, except that they ultimately learned the coat was similar to those worn by Alexander's security guards. (Berkowitz had been employed as a guard by IBI Security.) The day ended with the completion of the profile sketch and a promise from Strano that the hunt for the parking tickets would continue.

It is important to remember that at no time were the summonses connected to Son of Sam himself. Son of Sam was in the yellow Volkswagen at the top of the park, the police believed; not in a Ford two blocks away on Bay 17th Street. Yes, a Ford was ticketed at the hydrant. And yes, Mrs. Davis said that car later moved. But that revelation meant nothing because she didn't connect the Galaxy driver with the man who later passed her on foot, although they appeared similar to her. Moreover, she knew the police believed the killer drove a yellow VW, knowledge which further disassociated the Galaxy and the man on the street in her mind.

The tickets were of interest to the police for two reasons. First, a potential witness might be found. And even more importantly, the discovery of the summonses would confirm Mrs. Davis' story. Their existence would guarantee she was on the block at the right time on the right night. Without the citations, her entire story was suspect. And so, the search continued.

The press knew nothing of Mrs. Davis and nothing about the massive, all-out hunt underway for the yellow Volkswagen. At a press conference on August 1, Chief of Detectives John Keenan calculatingly said the reports of a yellow VW appeared to be of little significance.

Deputy Commissioner Frank McLoughlin added: "We have nothing more substantial than a general description [of the killer] and possibly a yellow Volkswagen." McLoughlin also stated: "Some neighbors thought they saw more than one car." There it was, a heady comment. But it wasn't pursued.

Instead, the media extensively covered Stacy's death and funeral arrangements. The News, however, by virtue of another leak from Brooklyn, reported that Violante and Stacy had encountered a "weird onlooker" in the park shortly before the attack and that police believed the man was the killer.

The paper, quoting the police allegedly quoting Violante, said: "He kept staring at us, almost scowling, and just stood leaning against a tree or something." This was a false kernel of corn purposely planted by the police. The man wasn't leaning against a tree; he was lounging against the brick rest-room building. The real killer would know that, and if and when he was arrested, the police could use that fact as a "key" in determining if a confession was legitimate.

Berkowitz would say he was sitting on a bench, and he'd be allowed to get away with it.

On August 3, Howard Blum of the New York Times wrote an article encapsulating the police investigation. Deputy Inspector Dowd was quoted, but he carefully avoided mentioning the VW chase or any of the numerous solid leads the police were working on.

Although through no fault of Blum, who was only reporting what the police were thinking, the article actually said eyewitnesses to the various shootings provided descriptions that "have resulted in four different drawings by police artists of the killer. In these composite sketches, the suspect is a white male between 20 and 35 years old, whose height ranges from 5 feet 7 inches to 6 feet 2 inches and who weighs anywhere from 150 to 220 pounds. The descriptions are so varied that the police are now considering the possibility that the killer wears various disguises, including wigs and mustaches, and has gained weight to complicate further his identification."

Didn't anyone think it was possible that the descriptions were so contrasting because more than one, solitary gunman was responsible for the shootings?

On August 4, police artist Bill McCormack and Cacilia Davis completed a facial view of the man on Bay 17th Street. Now the police had two sketches, front and profile, based on Tommy Zaino's description of the killer, another drawing from the recollections of VW chaser Alan Masters and the two Da- vis composites. The detectives sought out the Vignotti's for the second time to ask again about the man who approached the yellow VW on Shore Parkway an hour before the shooting.

The young couple, the report says, "picked out Sketch #301 as being the description of the Son of Sam." This clearly demonstrated that the police believed the man who walked to the VW was the killer.

The sketch chosen by the Vignotti's was the profile sketch drawn from Mrs. Davis' description—showing a clean-cut, youngish man with short, dark, wavy hair. The difference between the man the Vignotti's saw and the one spotted by Mrs. Davis—Berkowitz—was that Berkowitz was noticeably taller and wore a denim jacket with rolled-down sleeves while the Vignotti suspect was clothed in a light-colored shirt with the sleeves rolled up. Significantly, the Vignottis added that the nose of the man they saw was "flatter" than that of the original Davis composite.

The media were clamoring for the release of a new sketch, and police officials wanted to accommodate them. But not yet, not without the tickets and not with the controversy raging over who saw what, and whom.

On August 5, reporters Carl Pelleck and Richard Gooding of the Post wrote a page one story under the banner headline "SAM: COPS GET HOPEFUL." The article said that officials had arrived at a "new, more exact composite drawing of the most-wanted man, which police expect to circulate publicly today. . . . Sources who have seen the new sketch say it bears a close resemblance to an earlier one based on a description by Joanne Lomino after she and her friend Donna DeMasi were gunned down Nov. 27 .. . in Floral Park."

That was a long-haired sketch; and the Post's source was noting its similarity to the Zaino description from Brooklyn. But the source was premature. Zaino's composite would be held back and a combination VW driver-Davis sketch would be released four days later. But the article is illustrative of the confusion in police circles at the time—a confusion born of trying to turn two distinct people into one person.

In the end, the police decided to believe all the witnesses. But first, they had to develop the proper scenario and have it fit only one man—Son of Sam—not "Sons of Sam."

Mrs. Davis wasn't pleased with the flat nose the adjusted composite showed, maintaining it was actually sharper and "hooked, like an Israeli's or an Indian's." But Zaino, Masters and the Vignottis all said the nose was flat—and that feature would survive and remain on the composite. (Berkowitz's nose is pointed, as Mrs. Davis said.)

Then there was the issue of the killer's hair. The Vignottis and Mrs. Davis each portrayed a man with short, dark, curly hair. Zaino and Masters both totally disagreed. Violante's description of the "grubby hippie" in the park was similar to theirs.

On August 6, the beautician called the task force in Queens to report the man she'd spotted fleeing the park wearing "a light-colored, cheap nylon wig." That phone interview helped settle the matter, although the police already were leaning toward the wig theory.

Now, with the beautician's statement, the police thought they had a complete picture: The Vignotti's saw the man shortly after he arrived. He was scouting the area and was about to enter the VW when he spotted them and decided he'd better get away from his car. He was not wearing the wig at that time. Later, with the wig on, he was seen in the park by Stacy and Robert. A third police interview with Violante produced the following comment: "It could have been a wig."

Then, for some reason, the man wandered over to Bay 17th Street and, with the wig in his shirt, walked past Mrs. Davis. Returning to the park, he put on the wig, shot the young couple and fled. The beautician saw him running from the park, still wearing the wig, and it was still in place when he nearly collided with Masters at the red light up the block.

Zaino's sketches were withheld, as was that of Alan Masters. Police believed those witnesses, and Violante, saw the gunman with his wig on, and thus prepared to release the short-haired composites instead. But the face would remain that of the VW driver, primarily, and the nose would stay flat.

After the arrest, many observers would remark that, with the exception of the hair, the final sketch—purportedly Mrs. Davis'—didn't resemble Berkowitz. It didn't because the po- lice unknowingly took two men and turned them into one composite. But the fact that they did is yet another example of how certain authorities were that the VW driver was the killer. And that drawing would be released August 9, only one day before Berkowitz's capture.

Still to be resolved was the issue of the killer's clothing. Zaino, Masters and the Vignotti's all said the man was wearing a long-sleeved, light-colored shirt with rolled-up sleeves. Violante agreed on the sleeves but, in the darkened park, was uncertain as to whether the gunman was wearing a shirt or a denim jacket.

Mrs. Davis insisted that her suspect was wearing a dark blue denim jacket with rolled-down sleeves—an observation police didn't challenge since the sleeve, which hid the supposed gun, was an obvious and critical element of her story.

Apparently, the police didn't consider the implications of the scenario they were creating: The killer had worn a shirt with rolled up sleeves at 1:30 A.M. on the street, and was in the park with the sleeves still rolled up at 2:20. But now, two blocks away at 2:33, they were down—and he was now wearing a denim jacket. Then, two minutes later, the jacket had disappeared and the sleeves were rolled up again on the light colored shirt as he pulled the trigger.

It is stretching credibility to believe that one man was accomplishing all these wardrobe adjustments. But the fact is, the police missed the significance of the sleeves. Strano had written in his report that Mrs. Davis' suspect was carrying a gun. Some detectives didn't believe that, but the brass did, so that made Mrs. Davis' man the killer. And it also made him the VW driver.

Beyond that, the Police Department had concocted a single murderer months before, and that's the way it would remain. To justify their position, Strano told Mrs. Davis the man she saw had a large stomach "because he stuffed the wig in his shirt." And after the arrest, when Berkowitz, claiming to be the killer, said no wig was worn—ever—the police suggested to Zaino that Berkowitz might have "doused his hair with water to make it look long and straight.'

At no time were the witnesses in contact with one another. None knew the others existed. Zaino later said to me: "How could that Mrs. Davis say he was wearing a jacket? He was definitely not wearing a jacket."

Likewise, Violante was astounded: "How could she say he looked so neat? The guy I saw looked like a bum."

But after the police combined the descriptions into one sketch, they still waited, pending the discovery of the elusive parking tickets which would substantiate Mrs. Davis' story— and her suspect.

Meanwhile, the search for the yellow VW was building to mammoth proportions.

The Vignotti's didn't know the model year of the yellow Beetle they saw by the park when "Son of Sam" approached it. Neither did Robert or Paula Barnes, who noticed two people climb from the car at about 1:10 A.M. How the police were dealing with the "two people" is unknown. Maybe they decided the couple were mistaken about its multiple passengers. Or perhaps the police didn't know what to think.

In any event, Dominick Spagnola, who was parked on the service road at about 1:25 A.M., was a tow-truck driver by trade. The police interviewed him on two occasions, and Spagnola decided the car was of either 1972 or 1973 vintage with New York plates and a black stripe above the running board area. Alan Masters also described the VW he chased as a Beetle-type car.

But then something happened. It is unclear exactly what it was, but the police, on about August 5, decided the vehicle probably wasn't a VW bug at all—but was likely a 1973 yellow VW Fastback. At night, and from the rear, the cars were similar in appearance. And a rear view is what most witnesses had. Moreover, with its taillights extinguished, as the VW's were, the Fastback—which is a few inches longer than the Beetle and has a somewhat different trunk configuration—was even more easily confused with the more familiar bug.

However, my investigation later determined the car apparently was a bug—a 1971 model—faded yellow in color and with a front bumper that hung low on one side. But if a Fastback was on the scene, it may have been the auto flashing its lights on Bay 14th Street, or the car that followed cyclist Michelle Michaels.

But what appears to have happened is that the police, in an attempt to learn the VW's plate number, put chaser Alan Masters under hypnosis (apparently he came up with the numbers 684) and out of that session arrived at the Fastback conclusion.

An August 7 police report sums up details about the car, which also contained a CB radio and a long antenna, that were uncovered in that apparent hypnotic experiment. The following functions were performed utilizing . . . printouts, available information and resources:

A. Search NJ Printouts 198 combos 4-GUR, VW 4-GVR, no VW fastback

B. Search NJ Printouts 72 combos 684- VW GUR-GVR, no VW fastback

C. Search NY Plates 12 combos 684- Computer GUR-GVR, negative results

D. Search NY Plates 684 GUR-GVR, 2 Computer hits, registered owners

E. Inquiry NCIC [a 99 combos 4-GUR, 2 federal crime data plates stolen bank]

F. Hand Search NJ Printouts, all 1973 VW fastbacks, BG [beige], TN [tan], YW [yellow]. 300 of 200,000 [300 of the described autos out of a total of 200,000 VWs]

The following items are in the process of being completed as of this date:

a. request printouts 1973 fastbacks NY DMV (possible 600-4.00,000 autos)

b. Personal observation of each 1973 VW fastback from NJ & NY printouts (possible 900 autos)

This was a remarkable document. The police were planning to "personally observe" 900 VW Fastbacks from New York and New Jersey—an awesome task—in a massive, all-out effort to locate the car and the killer. How serious was the NYPD about the yellow VW? That strategy adequately answers the question.

The other license plate combinations available were 463, which was observed by the nurse who saw the VW fleeing on 17th Avenue; and 364. The 364 was a number the police apparently ignored because its significance was missed.

The 364 was written on the back of an anonymous postcard, postmarked in Brooklyn, that was mailed to the Moskowitz home on August 4. It was turned over to the police. The numbers were scrawled in the center of the card; below them were the words "Son of Sam." It was the exact reverse of the nurse's 463 and a common visual interpretation of the "possible 684" the police already had. Somewhere in these combinations was the key to the actual plate number.

But it was already August 7. The arrest of David Berkowitz was only three days away and would occur before the police got very far with the leads on the license plate numbers. And after the arrest, the investigation was immediately halted.

In the interim, teams of detectives began to scour the metropolitan area, checking VWs and other small yellow cars whose plate numbers were similar to those reported by the witnesses.

Other detectives drove to the NYPD's photo bureau, where, under job #2361, they obtained several thousand photographs of a yellow VW for possible mass distribution in the event the department decided to reveal the entire focus of its case. But the arrest would occur before the pictures were released.

It was now August 9, and the wayward tickets were finally discovered in the 62nd Precinct. Officers Cataneo and Logan 112 On Terror's Trail had written four in the Bay 17th Street vicinity shortly before the shooting. One of those had been slapped on the windshield of a 1970 four-door Ford Galaxie, cream-colored, black vinyl roof, New York registration 561-XLB. At 2:05 A.M. on July 31, a half hour before the attack, the car was tagged for parking too close to a fire hydrant in front of 290 Bay 17th Street, a brick garden apartment building in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn.

With the tickets at long last located—nearly a week after Mrs. Davis told Strano of their existence—the widow's story was substantiated and the police quickly released the final composite sketches. When the drawings, a frontal view and a profile, flashed across television screens, about 200,000 young Hispanic males dove for cover, as the full-face sketch bore a resemblance to any number of young men of Spanish origin. And as many observers also noted cynically, the picture looked strikingly like Herman Badillo, a U.S. congressman from New York City.

The sketches were at such variance with composites released after earlier .44 attacks that Chief of Detectives John Keenan held a press conference to disclose the thinking of the NYPD's top officials. Keenan explained the drawings were primarily the result of the recollections of a single witness which were corroborated by several others. Keenan stated that the NYPD believed the killer had been wearing wigs all along.

Son of Sam's new face was spread across the front pages of the city's newspapers. The News incorrectly reported that "Tommy Z." had provided the latest description and "was so close to the attack that he was able to describe tiny, kidney shaped designs spaced three inches apart on the killer's bluish gray Qiana shirt."

Interestingly enough, this shiny Qiana shirt, which Mrs. Davis said Berkowitz had worn under his shirt, in no way resembled the coarser, uniform-type gray shirt observed by Zaino, Masters and Violante. This contradiction was beyond the jacket-off, jacket-on, sleeves-up-down-up discrepancy noted earlier.

The Post, getting closer to the truth through its own police sources, responded with a banner front-page story which was headlined "NEW WITNESS SAW SAM CHANGE WIG." Written by the able Carl Pelleck, the article said a new "secret witness . . . has been able to describe him without the wig or wigs cops now believe he's been using all along as a dis- guise. . . .

"Police would not say whether the witness saw the killer without his wig before he attacked or after the shootings.

"There were other witnesses to the Moskowitz killing who saw different stages of the attack. . . . The others saw him as a man with long, disheveled hair which police now believe was a cheap, light brown wig."

Thirty-six hours later, the Police Department would deeply regret that proclamation when Berkowitz, claiming to be the killer, would assert that he never wore a wig. And he was right: he never did. But he wasn't the man who pulled the trigger either.

But on August 9, the pressured hunt for the killer's yellow VW continued in earnest. The media knew nothing about it, and in fact knew none of the details which led to the NYPD's conclusion about the wig. If the press had been aware of some of these facets, the arrest of Galaxie driver David Berkowitz might not have been so readily accepted as the total solution of the case.

But the media and public were misled. With the secret aspects of the investigation now revealed, this much can be said about David Berkowitz as the "lone" .44 killer:

For Berkowitz to have been the slayer of Stacy Moskowitz, the entire hierarchy of the NYPD—and the total thrust of the monumental investigation—had to have been 100 percent wrong.

Keenan's press conference was over, the sketches were on the street and tomorrow was coming. And to Detective James Justus, the night of August 9 was shaping up in routine fashion in the offices of 10th Homicide in Brooklyn's Coney Island section. Justus was a veteran detective who was normally as- signed to Brooklyn Robbery. But he was temporarily pitching in at the 10th during the Sam investigation.

Working the evening shift, Justus was looking at a computer printout which listed the owners of the cars ticketed on Bay 17th Street the night of the shooting. It was Justus' job to contact the car owners to ask if they'd seen anything of value while in the neighborhood.

Dialing the phone, Justus eliminated two of the owners, and at about 7 P.M. he typed up DD-5 #271. A great deal of false information would later be released about the events of this night, and some would exaggerate and distort them for obvi- ous, but insidious reasons. But here is what actually happened:

At the typewriter, Justus wrote:

Subject: INVESTIGATION AS TO POSSIBLE WITNESSES TO THIS CASE:

1. Check of summonses served in the area of this crime disclosed there were four (4) served thereat as follows:

A. 0210 hrs. . . . F/O 262 Bay 17 St. reg #XXX-XXX. Registered to Robert E. Donaldson* of 20 First St.,* Staten Island. Phone EL-0-0000.

B. 0210 hrs. .. . F/O 262 Bay 17 St. reg #XXX-XXX. New reg not in computer as of this date.

C. 0205 hrs. .. . F/O 290 Bay 17 St. reg #561-XLB. Registered to David Berkowitz of 35 Pine St., Yonkers NY. Phone (914) 000-0000.

2. Check re Donaldson disclosed that owner is deceased and the auto was being used by the son of Mrs. Donaldson. Son was alleged to be at a party in Brooklyn on the night of this crime. Son's name is James, DOB 1/3/53. A message was left thereat for the son to contact this command regarding this case.

3. Check with Berkowitz disclosed that there is no answer on phone.

The thought of what Justus might have been told had he reached "potential witness" Berkowitz is, despite the seriousness of the subject, amusing to ponder. But that didn't happen. Instead, about ninety minutes later, at 8:25, Justus called Berkowitz again. Still no answer. Justus was tired of dialing the phone, so he decided to let the Yonkers Police Department give him some assistance.

Justus called the information operator and obtained the listing for the Yonkers Police Department's main switchboard. The phone was answered by a female dispatcher:

"Police Headquarters, 63."

"Hello, this is Detective Justus, Brooklyn Police Department."

"Yes?"

"We would like to get a notification made up there in Yonkers."

"Yes, all right. Hold on."

In a moment, operator 82 would come on the line, replacing 63.

David Berkowitz was now just twenty-four hours from his appointment with destiny.

Detective James Justus had absolutely no idea that anything of

interest was about to come his way as he waited for the Yonkers

police operator to return. To him, this call was strictly

routine. He'd tried four times to reach Berkowitz without

success. For all he knew, the man was out of town. The supervisors

wanted this witness thing cleared up, so he'd ask the

Yonkers cops to notify Berkowitz and have him call the 10th.

Then Justus could get on with more pressing matters in the

investigation; specifically the matter of the yellow VW. In a

moment, a new Yonkers operator was on the line.

Detective James Justus had absolutely no idea that anything of

interest was about to come his way as he waited for the Yonkers

police operator to return. To him, this call was strictly

routine. He'd tried four times to reach Berkowitz without

success. For all he knew, the man was out of town. The supervisors

wanted this witness thing cleared up, so he'd ask the

Yonkers cops to notify Berkowitz and have him call the 10th.

Then Justus could get on with more pressing matters in the

investigation; specifically the matter of the yellow VW. In a

moment, a new Yonkers operator was on the line.

82. Police Headquarters, 82.

JJ. Yes, this is Detective Justus from the Brooklyn Robbery Squad, New York City Police Department.

82. Yes . . .

JJ. I'm working in the 10th Homicide Zone now, on the .44- Caliber Killer.

82. Yeah . . .

JJ. And I'm trying to contact a party that lives up in Yonkers who is possibly a witness to the crime down here. That's a Mr. David Berkowitz . . .

82. Oh no .. . oh no . . .

JJ. Do you know him?

82. Could I .. . I was very involved. This is the guy that I think is responsible . . .

JJ. David Berkowitz? [Justus must have thought he'd wandered into the Twilight Zone. Berkowitz drove a Ford, not a VW.]

82 .. . is responsible. My father was down there yest—Saturday.

JJ. Yeah . . .

82 .. . and you also got information regar . . . Is he at 35 Pine Street?

JJ. Yes, dear.

82. David Berkowitz. I don't know how you, or what, but my father went down to the 109th and you also . . . someone received information through our police officers and that's because of some incidents involving shooting where we have reason to believe this person is responsible. He also has written similar-type threatening letters to the sheriff's investigator who recently moved into his apartment. So, I don't . . .

JJ. Do you know David Berkowitz yourself?

82. I don't know him. I, really, because of a shooting incident at my home and a firebombing and threatening letters . . .

JJ. At your home . . .

82. .. . and through investigation found out that this is probably the person.

JJ. Did you notify the Police Department on it?

82. Oh, yeah, there are numerous reports on it, and information regarding this guy was given to your department on Saturday.

JJ. Yeah, well, I am doing it another way. He got a summons down here that night, right in the vicinity . . .

82. Oh my God .. . he .. . he .. . you know, because we have seen him and he fits the description. This is why my father went down there with his whole file of copies of letters we have received from him. And I believe the Westchester County Sheriff's Department is now investigating him because he threatened a sheriff's investigator . . . My dog was shot with a .44-caliber bullet.

JJ. Oh, really?

82. At least that's what it was supposed to have been. The people who have seen it claim it was a .44 . . .

JJ. Ah . . .

82. [Laughing] . . . He, he just scared me to death . . . now you are telling me he's a witness.

JJ Well, we don't know. A possible witness. And from what you're telling me, a possible perpetrator.

82. .. . And he owns a yellow car.

JJ. He has a yellow . . . yeah, I'd say a yellow Ford, I believe it is . . .

82. Yeah . . . yeah .. . do you—the 109th, is that Brooklyn?

JJ. No, that's Queens. We're working on it out of the 10th Homicide Zone in Brooklyn.

82. O.K. . . . well, he went .. . my father went to the 109th on Saturday. Last week someone was up here at our intelligence unit and at that time spoke with officers Intervallo and Chamberlain and they gave him information . . . just on a long shot, now, because he does resemble the picture. I don't know him personally.

JJ. All right, so you know of Berkowitz . . .

82. Right.

JJ. Through . . . ?

82. Incidents that have occurred that I have reason to believe that you could prove in court that he's responsible for a shooting incident at my home . . .

JJ. Yonkers had at home and believes Berkowitz responsible . . .

82. He happens to be .. . He either was or is now employed as a rent-a-cop, like a security guard.

JJ. Rent-a-cop . . . you use the same terms we use down here, huh?

82. Yeah.

JJ. Your dog shot . . .

82. With a large-caliber bullet. It's never been confirmed because you know how it happens, right? Seventeen people have seventeen different jobs and nobody gets together and it's only in the last week that these two cops and I got together and put all the reports together and got the DD [detective division] reports where he is doing everything . .

JJ. Let me ask you something, honey. With his name, do you have a pistol license bureau up there that would . . . ?

82 O.K., supposedly he has a permit to shoot by New York City or has an application now being processed in relation to this . . .

JJ. .. . in New York City . . .

82. He holds no permit in the city of Yonkers at this time.

JJ. But possibly here in New York City . . .

82. Possibly, because he was employed as a security guard. Well, you know who you should get in touch with? And if you will hold on a minute, I will find out when he's working .. . all right .. . it is either police officers Chamberlain or Intervallo who for their own reasons put this all together, just because it happens to be their sector where I live.

JJ. Chamberlain or Intervallo?

82. Yes.

JJ. Would you be able to do me the honors, please?

82. Well, I'll find out where they are. They are not working right now. I know that. Can you hold on a minute?

JJ All right. [Justus, on hold, speaks to people in his office.]

JJ I have something beautiful here. I wanted to talk to this guy about a summons . . . lives up in Yonkers. I was talking to Yonkers to get a notification made and she says, "Oh, not him, he shot my dog with a .44 about a month ago. He's crazy! He's sending threatening letters to the deputy sheriff's office . . ."

82. Could I get your name and have someone call you back?

JJ. All right. My name is Justus. Uh, I'm thinking about what the hell number to give you. I'll give you this one, 946-3336, and that's a 212 exchange ... . Can I ask you a favor, honey? Operator 82, can I get your name, please?

82. Sure. My name is Carr. C-a-r-r.

JJ. First name, honey?

82. Wheat . . . W-h-e-a-t. Now, my father, my father is Samuel Carr. He went down there with all the information the other day.

JJ. Where do you live, Miss Carr?

82. 316 Warburton Avenue, and that is immediately behind— the back of his house and the back of mine . . . face each other. There is also a Westchester County Sheriff's Department investigator because he wrote letters to this investigator who has the apartment beneath him saying that my father planted him there and he is going to get us instead. But I'll have Pete or Tommy call you back . . . I'll call them at home . . .

JJ. Do you know how to spell the last guy's name? Not Chamberlain . . .

82. I-n-t-e-r-v-a-l-l-o. Just like it sounds.

JJ. Okeydoke, honey.

82. Thank you a lot.

JJ. Thank you very much, dear.

82. Bye-bye.

This transcript of the actual conversation between Wheat Carr and Justus hasn't been made public before. It vividly shows what role the NYPD believed Berkowitz played in the Son of Sam saga and invalidates numerous police proclamations which followed the arrest, when authorities claimed they initially were highly suspicious of Berkowitz.

Wheat Carr was a police and gun buff—owning a .357 Magnum, a .25-caliber revolver and a .22-caliber pistol. She had a mother named Frances and a black Labrador retriever named Harvey. She also had a brother named Michael, twenty-four, a freelance advertising stylist, photographer and designer who was a ranking member of the Church of Scientology.

At that minute, her other brother, thirty-year-old John Carr, was on the road. New York was far behind him as he crossed the midwestern United States, angling north. John Carr had his reasons for vacating the metropolitan area. And his reasons involved David Berkowitz.

After hanging up from her conversation with Justus, Wheat called her family home at 316 Warburton Avenue—a rambling, old three-story frame house where her father, Sam, operated an answering service.

Warburton Avenue, once a thriving middle-class thoroughfare of private homes, apartment buildings and small businesses, had gone downhill since the early 1960s. Its southern portion, in which the Carrs lived, was somewhat seedy. High above, at Pine Street, the neighborhood changed for the better. David Berkowitz's building was newly renovated and well maintained and commanded a majestic view of the Hudson. The apartment house, contrary to Wheat Carr's implication, was not situated very close to the Carr home. The impression given was that the two dwellings were practically back to back. Not so. About two hundred hilly yards consisting of trees, the Croton Aqueduct path and Grove Street separated Berkowitz's apartment from the Carr home far below.

Sam Carr, sixty-four, a thin, gray-haired, chain-smoking retired Yonkers Public Works employee, who himself owned several guns—including revolvers—listened as his daughter repeated the essence of her exchange with Justus.

Carr hung up and called Justus in Brooklyn. About two hours later, at 10:30 P.M., Wheat Carr reached Yonkers police officer Tom Chamberlain at his home and Chamberlain, too, called Justus. Bit by bit, the NYPD was learning about potential witness David Berkowitz, and the story Justus was hearing was a fascinating one.

The Cassaras' other children were grown and living their own lives in the Westchester area. Jack Cassara, still short of retirement age, worked at the Neptune Moving Company in New Rochelle.

Berkowitz, a model tenant, had complained about the barking of the Cassaras' German shepherd dog, but otherwise was friendly and no bother to the family. He paid his $200 monthly rent on time. However, he abruptly moved from the Cassara residence in April 1976, leaving his $200 security deposit behind. He'd been there only two months.

Berkowitz left New Rochelle for apartment 7-E on the top floor of 35 Pine Street in northwest Yonkers. Nobody seemed to know how he'd found the Cassara home or the Pine Street address. His Yonkers rent was $237 a month, which he paid punctually.

On May 13, 1976, a Molotov cocktail firebomb was tossed at a second-floor bedroom window in the home of Joachim Neto, 18 Wicker Street, Yonkers, a two-family, wood-frame house located down the hill from 35 Pine and no more than fifty yards south of the Carr home. Neto, his wife, Maria, her mother, and their daughter, Sylvia, thirteen, lived on the first two floors, and a construction worker occupied the top floor by himself. The Netos received a number of abusive telephone calls and at least one threatening letter, which Mrs. Neto's mother destroyed.

On October 4, 1976, at about 4:40 A.M., someone threw a Molotov cocktail through a window in the Carr home. Sam Carr, awake at the time, extinguished the flames before the firefighters arrived.

Eleven weeks later, on Christmas Eve, the Netos were entertaining a large gathering of family and friends when several shots, fired from a car through a chain link fence fronting the house, slammed into the dwelling, barely missing a window behind which young Sylvia Neto was playing the piano. But on the front stoop, the family German shepherd, Rocket, lay dead. A bullet from a small-caliber weapon had sliced through its neck.

On April 10, 1977—Easter Sunday—a handwritten letter was mailed to Sam Carr asking him to silence the barking of Harvey, the black Labrador retriever. On April 19, another letter—written by the same hand—was sent to the Carr residence. This missive was more threatening in tone than the previous one.

On April 27, at about 9:30 A.M., somebody made good on the threat. Harvey was wounded by one of the several shots pegged into the Carr backyard from the aqueduct path some twenty yards behind the house. Carr got a glimpse of a man in blue jeans and a yellow shirt running north on the aqueduct. The shooting was not done with a .44, as Wheat Carr implied it was.

Next, on June 7, Craig Glassman, a nursing student and volunteer deputy with the Westchester County Sheriff's Department, received the first of four threatening letters mailed to his apartment at 35 Pine Street, where he'd moved in March from around the corner on Glenwood Avenue to apartment 6E, directly below David Berkowitz.

Two days later, on June 9, the Cassara family in New Rochelle—Berkowitz's former landlords—received a get-well card in the mail. The card, which was decorated with a drawing of a puppy, told Jack Cassara: "Sorry to hear about the fall you took from the roof of your house ... " Cassara had taken no such fall. The card was signed: "Sam and Francis" (sic), and the envelope was embellished with the return address of the Carrs, whom the Cassaras didn't know. Both annoyed and curious, Mrs. Cassara located the listing for Sam Carr and phoned him to discover why the card was sent. The Carrs said they knew nothing about it; but Sam Carr told Nann Cassara about the letters he'd received and the subsequent wounding of Harvey, who still had a large-caliber bullet in his body. It was deemed too risky to remove it, Carr said.

The two couples agreed to meet, and on June 9, at the Carr home in Yonkers, they compared the handwriting on the Carr letters with that on the Cassaras' get-well card. The samples matched. Something was happening in Yonkers. Something strange. The Carrs and Cassaras had something or someone in common. But they couldn't decide who, or what, it was.

Back at home that evening, Nann Cassara talked about the Yonkers visit with her son, Steve. Hearing about the attack on the Carrs' dog, Steve suggested: "Remember that tenant we had who didn't like our dog barking? Maybe it's got something to do with him."

Recalling the incident but not the tenant's name, Nann Cassara checked her records. David Berkowitz. She next looked in the Westchester telephone directory and noticed a listing for a David Berkowitz at 35 Pine Street in Yonkers. She phoned Sam Carr.

"Is Pine Street anywhere near you?" she asked. Bingo.

The next day, June 10, Carr went to the Yonkers Police Department detective division with the information he'd received. To say the Yonkers detectives mishandled the case would be to understate the matter. But, in short, nothing happened. This was on June 10, sixteen days before the Elephas shooting and seven weeks before Son of Sam attacked Stacy Moskowitz and Robert Violante.

Volunteer sheriff's deputy Craig Glassman, meanwhile, had carried his June 7 threatening letter to his superiors in White Plains. Nothing happened there either. Glassman received another mailed threat, postmarked July 13. He again showed the letter to his superiors. If someone had bothered to check with Yonkers police, they would have learned the handwriting on Glassman's letters matched that on the Cassara get-well card and on the Carr letters about Harvey. But no one bothered.

But on Saturday August 6, a week after the Moskowitz-Violante shooting,everyone began answering reveille's bugle. At seven-thirty that morning, someone started a garbage fire in front of Glassman's door at 35 Pine Street and flung about two dozen live rounds of .22-caliber bullets into the flames for good measure. Luckily, no one was injured.

One of the Yonkers police officers who responded to the blaze was Tom Chamberlain, who was familiar with the Carr and Cassara correspondence. He asked Glassman if he'd received any mailed threats. Glassman showed him the two letters he'd received as of that morning and Chamberlain immediately recognized the handwriting. This was not a monumental feat: Berkowitz's writing is distinctive and easily identifiable.

And more than that, Glassman's June letter contained the return address of the Cassaras and the July 13 note actually had Sam Carr's last name in it.

Glassman's notes also were spiced with references to blood, killing and Satan. Suddenly, everybody wanted a piece of David Berkowitz.

The stories related by Chamberlain and Sam Carr to the NYPD's James Justus were of interest in the waning hours of August 9. But despite the violence, gore and bizarre conduct loose in Yonkers, the Brooklyn supervisors weren't overly impressed—although they'd later claim they were. There were, they knew, thousands of borderline psychotics in New York, and Berkowitz—if he was indeed guilty of the war being waged in Yonkers—might only be another in a long list of erratic citizens whose names were being forwarded to the Omega task force every day. Moreover, this blatant, wild activity didn't at all jibe with numerous psychiatric portraits of a low-keyed killer who "would melt into the crowd." On the surface—Joe Ordinary. And that was, and is, an important point.

The NYPD did not storm into Yonkers that night; nor would they unleash a battalion of detectives the next day. They'd send two—only two—detectives to conduct a routine check of "potential witness" Berkowitz, who was of interest because of the ticket and the allegation that he was now suspected of violent behavior involving a weapon as well. He didn't drive a yellow VW—the killer's car—and he didn't borrow it: his own Ford was at the scene that night. But it was remotely possible he somehow switched vehicles. Anything was possible.

It is interesting to note that on Wednesday, August 10, Police Commissioner Michael Codd was out of town. Not in Europe or China; just out of town. John J. Santucci, district attorney of Queens, site of five of the eight Son of Sam attacks, would later offer this observation: "If you knew beforehand that you had identified your suspect, you just would not make the biggest arrest in the history of the Police Department without the commissioner available. It's simply not done. They didn't know until the very end it was Berkowitz they were after." At around noon on the tenth, Detective Sergeant James Shea of the 10th Homicide Zone asked veteran detectives Ed Zigo and John Longo to drive to Yonkers to look into the Berkowitz situation. Strano and Justus, who'd carried the issue to this point, were excluded from the excursion—another indication that Berkowitz wasn't believed to be the killer. If an arrest was thought possible, the two cops who built the case probably would have been on the scene.

Arriving in Westchester, Zigo and Longo used a street map for reference and cruised along North Broadway in Yonkers, turned left on Glenwood and proceeded down the hill to Pine Street. They stopped, walked around the area and spotted Berkowitz's Galaxie parked on the west side of the narrow road about twenty-five yards north of the entrance to No. 35. Zigo gazed through the car window and spied a duffel bag in the back seat. A rifle butt was protruding from the bag.

There is no law in New York that prohibits possession of a rifle. Rifles aren't considered concealed weapons, and it isn't even necessary to obtain a license before owning one. Zigo, peering through the window, knew that. He also knew he could see only a butt, or stock, and nothing more. In other words, he had no reason to think any illegal material was in the vehicle.

Regardless, he entered the car. Opening the duffel bag, he saw the rifle was a semiautomatic Commando Mark III capable of firing thirty bullets from any of the assortment of clips that were also stashed in the duffel bag. The gun, although not of the type normally owned by hunters or "average citizens," was not illegal.

Popping the glove compartment, Zigo came across an envelope addressed to Omega commander Timothy Dowd and the Suffolk County, Long Island, police. Reading the enclosed note, Zigo knew what he'd found. The text, in longhand, promised an attack in Southampton, the exclusive summer re- sort on Long Island's south shore, not far from Fire Island.

Zigo and Longo were thunderstruck. They'd located the Son of Sam. Or had they?

David Berkowitz had spent an eventful, busy week. Plans were formulated and enacted. Wheels were set spinning. An elaborate mystique had to be created. It had been difficult to accomplish, but it was done.

While Zigo poked through the Ford, Berkowitz—whose apartment didn't face the street—paced the living area. Earlier that morning, he'd gone downstairs and put the duffel bag into the car and jammed the hastily scrawled note into the glove compartment. The letter was written in longhand. There hadn't been time to copy the stylized, slanted, block-letter printing of Son of Sam. He'd also plagiarized a poem—apparently inspired by another individual—adapted it to Craig Glassman, wrote it on a manila folder and drawn the Son of Sam graphic symbol beneath it. He sketched the symbol incorrectly, reversing the Mars and Venus sign positions from the original used in the Breslin letter and adding arrows to the ends of the "X." (A Yonkers police official would later find pieces of paper on which Berkowitz practiced drawing the symbol.)

Berkowitz's printing also faltered in his attempt to mimic

the Son of Sam method. Unlike the letter to Breslin, which

contained only capital letters, the ode to Glassman was sprinkled with several lowercase letters done in the normal Berkowitz style of printing. One would have thought "Son of Sam"

knew his own techniques.

Berkowitz's printing also faltered in his attempt to mimic

the Son of Sam method. Unlike the letter to Breslin, which

contained only capital letters, the ode to Glassman was sprinkled with several lowercase letters done in the normal Berkowitz style of printing. One would have thought "Son of Sam"

knew his own techniques.

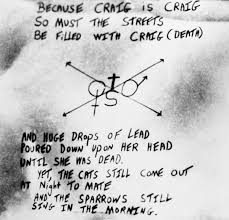

The poem said: "Because Craig is Craig, so must the streets be filled with Craig (death). And huge drops of lead poured down upon her head until she was dead. Yet the cats still come out at night to mate, and the sparrows still sing in the morning."

But why all the haste and hurry with the poem and letter?

David Berkowitz, sources close to him say, knew that the police were coming to Yonkers that day. He'd been tipped off. The implications of this revelation are staggering. Was Berkowitz really alerted? At this point, it is perhaps better to answer that question with several other questions: Did a means exist through which Berkowitz could have been alerted? Is it logical to believe that the infamous, ingenious Son of Sam—who'd eluded the biggest manhunt in New York history for so long— would leave a valuable, potentially incriminating weapon ex- posed in his own car which was parked in front of his own home in broad daylight? And with that weapon so displayed— inviting a break-in such as Zigo's—would that killer then leave a Son of Sam letter within easy grasp in his glove compartment? And would he do so in light of a parking ticket he knew would eventually lead the police in his direction—knowledge that should have led him to be doubly cautious?

In actuality, the initial preparations had been in the making since the day after the Moskowitz-Violante shooting. The parking ticket, the sources close to him state, had assured Berkowitz of the nomination, and the VW chase had cemented his election. He couldn't claim an innocent reason for his presence in Bensonhurst because doing so would have kept the police investigation centered on the yellow VW driver, who, it would be learned, was deemed more important in the conspiratorial hierarchy than David Richard Berkowitz. The police were after only one killer. Berkowitz could be tossed to the wolves, as the result of his own mistake. And the truth could remain a secret.

Berkowitz, the sources say, wasn't at all happy with the situation. But he had no choice. At first, it was hoped there was a remote chance the police wouldn't investigate the ticket at all—and he had paid it immediately. But it was far more likely they would pursue the matter routinely, so Berkowitz had to be ready.

On about August 4, less than a week after the Brooklyn attack, Berkowitz—with some assistance from his accomplices —removed his possessions from the Pine Street apartment in the dead of night. They included a bed, a couch, a bureau, a dinette set and assorted clothing. An expensive Japanese-made stereo system he'd purchased while stationed with the Army in Korea was disposed of by other means.

The clothing and furniture was loaded into a van rented from a Bronx gas station and carted to the Salvation Army warehouse in Mount Vernon, Westchester County, about five miles from Pine Street. The contents were piled in front of the building where they could be discovered when the facility opened the next morning.

Then, a series of "insane" notes had to be written and strewn about the apartment to enhance the illusion of a lone, demented Son of Sam. These letters railed against the Cassaras, the Pine Street neighborhood, Sam Carr and others.

Next, a number of weird ramblings and obscenities about Sam Carr, demons and Craig Glassman were slapped onto the apartment walls with Magic Marker. A hole was punched into one of the walls and surrounded by other bizarre writing.

The intent was plain: he was to feign insanity; and the "demonic possession" angle provided in May by the NYPD itself would serve as the motive for the slayings.

There were some mistakes made, but they would be missed or ignored by the police, who didn't concern themselves with any kind of follow-up investigation

It was, all in all, a brilliant hoax to pull on the naive NYPD. But as Berkowitz would later write to me in a modest vein: "It wasn't all my idea, and I'm certain you know this."

The police, under intense pressure, were so desperate for an arrest they'd believe almost anything, Berkowitz was told. Accurately. Nobody would challenge the story because nobody would want to do so. Accurate again. Politics was involved. The city was in shambles. You can tell them anything and they'll go for it just to bring this to an end. Berkowitz listened to the milk and honey, and he thought hard. There wasn't much he could do. So he bought the arguments about politics and the desperation of the police. And he agreed that he could get off on a "not guilty by reason of insanity" plea and be put into a mental institution. There, he was told, he'd either be released as a "cured" man in five to seven years' time—or else his friends would break him out. He knew that part was bullshit.

But it is not known what he thought fifteen months later when, unknown to the public, a loaded .38-caliber revolver was mailed to him at the Central New York Psychiatric Center in Marcy. The package, postmarked in Bayside, Queens, was intercepted by Center officials before it reached Berkowitz's hands. But he knew it had arrived for him.