The Atlantis Encyclopedia

by Frank Joseph

Atara

Among the Guanche, the original inhabitants of the Canary Islands, the word

for “mountain,” apparently derived from and related to the Atlantean mythic

concept of the sacred mountain of Atlas.

Atarantes

“Of Atlantis.” A people residing on the Atlantic shores of Morocco and

described by various classical writers (Herodotus, Diodorus Siculus, etc.).

Atas

Natives inhabiting the mountainous central region of Mindanao, a large

southern island in the Philippines. They tell how the Great Flood “covered the

whole Earth, and all the Atas were drowned except for two men and a woman.

The waters carried them far away.” An eagle offered to save them, but one of

the men refused, so the bird took up the other man and woman, carrying them

to safety on the island of Mapula. Here the Atas were reborn and eventually

multiplied sufficiently to conquer the entire Philippines. The Atas still claim

descent from these light-skinned invaders who, over time, intermarried with

the Negritos and aboriginal peoples.

Atauro

A small island near East Timor, memorializing in native tradition a larger

landmass, long ago swallowed by the sea.

Atcha

In ancient Egyptian, a distant, splendid, vanished city, suggestive of Atlantis.

The prefix “At” recurs among ancient Egyptian mythic figures associated with

overtly Atlantean themes (Atum, Atfih, At-hothes, etc.).

Atchafalaya

Known as the “Long River” to the Choctaw Indians of Louisiana. Its resemblance to the shorter Egyptian name Atcha is suggestive, especially in view of the

Choctaws’ own deluge myth. Here, too, “At” is used to identify water, one of the

three Atlantean themes (city, mountain, and/or water) associated with this prefix

by numerous cultures around the world.

Atea

The Marquesans regarded Atea as their ancestral progenitor who, like the

Atlanto-Egyptian Atum, claimed for himself the creation of the world. Fornander

wrote, “In the Marquesan legends the people claim their descent from Atea and

Tani, the two eldest of Toho’s twelve sons, whose descendants, after long periods

of alternant migrations and rest in the far western lands, finally arrived at the

Marquesas Islands.”

Like Atlas, Atea was his father’s first son and a twin. With his story begins

the long migration of some Atlanteans, the descendants of Atea, throughout

the Pacific. Fornander saw Atea as “the god which corresponds to Kane in the

Hawaiian group” and goes on to explain that “the ideas of solar worship embodied in

the Polynesian Kane as the sun, the sun-god, the shining one, are thus synonymous

with the Marquesan Atea, the bright one, the light.” Atum, too, was a solar deity.

Atemet

The dwelling place and/or name of the goddess Hat-menit, who was depicted in

Egyptian temple art as a woman wearing headgear fashioned in the likeness of a

fish. Worshiped at Mendes, where her title was “Mother,” she was somehow connected to the Lands of Punt often associated with the islands of Atlantis. Budge

believed Atemet was a form of Hathor, the goddess responsible for the world flood.

Atemet’s Atlantean name, fish-crown (queen of the sea), and connections to both

Punt and Hathor identify her with some of the leading features of the Atlantis story.

Atemoztli

Literally “the Descent of Waters,” or the Great Flood, as it was known to the

Aztecs. A worldwide cataclysm accompanied by volcanic eruptions, its few survivors arrived from over the Sunrise Sea (the Atlantic Ocean) to establish the first

Mesoamerican civilization. “Atemoztli” was also the name of a festival day commemorating the Deluge, held each November 16—the same period associated

with the final destruction of Atlantis (late October to mid-November). Atemoztli philological resemblance to Atemet, the Egyptian deluge figure, is clear.

Atennu

Egyptian sun-god, as he appears over the sea in the west. Another example of

the “At” recurring throughout various cultures to define a sacred place or personage with the Atlantic Ocean.

Atep

The name of the calumet or “peace pipe” in the Siouan language. The

Atep was and is the single most sacred object among all Native American tribes,

and smoked only ritually. It was given to them by the Great Spirit (Manitou)

immediately after a catastrophic conflagration and flood destroyed a former world

or age, which was ruled over from a “big lodge” on an island in the Atlantic Ocean.

The survivors, who came from the east, were commanded by the Great Spirit

to fashion the ceremonial pipes from a mineral (Catlinite) found only in the southwest corner of present-day Minnesota (Pipestone National Monument) and

Barron County (Pipestone Mountain), in northwestern Wisconsin. In these two

places alone the bodies of the drowned sinners had come to rest, their red flesh

transformed into easily worked stone. The bowl represented the female principle, while the stem stood for the male; both signified the men and women who

perished in the flood. Uniting these two symbols and smoking tobacco in the

pipe was understood as a commemoration of the cataclysm and admonition to

subsequent generations against defying the will of God.

The Atep was a covenant between the Indians and the Great Spirit, who

received their prayers on the smoke that drifted toward heaven. It meant a reconciliation between God and man, a sacred peace that had to be honored by all

tribes. The deluge story behind the pipe, the apparent philological relationship

of its name to “Atlas” or things Atlantean—even the description of the Indians’

drowned ancestors as red-skinned (various accounts portray the Atlanteans as

ruddy complected)—confirm the Atep as a living relic of lost Atlantis.

Ater

The Guanche Atlas, also worshiped in the pre-Conquest Canary Islands as

Ataman (“the upholder,” precisely the same meaning for the Greek Titan), and

Atara (“mountain,” Mount Atlas).

Ateste

The Bronze Age capital, in northern Italy, of the Veneti, direct descendants

of Atlantis.

Atfih

More of an Egyptian symbol than an actual deity, he supported the serpent,

Mehen, that protectively surrounded the palace in which Ra, the sun-god, resided.

Here, Atlantis is suggested in the serpent, symbolizing the Great Water Circle

(the ocean) and in Ra’s palace, center of a solar cult, while Atfih, whose name

means “bearer,” was Atlas, who bore the great circle of the heavens.

At-hothes

The earliest known name of Thaut, (Thoth to the Greeks, who equated him

with Hermes), the patron god of wisdom, medicine, literature, and hieroglyphic

writing, who arrived in Egypt after a deluge destroyed his home in the Distant

West. These western origins, together with the “At” beginning his name, define

him as an Atlantean deity. Arab tradition identifies him as the architect of Egypt’s

Great Pyramid on the Giza Plateau. Edgar Cayce, who certainly knew nothing of

these Arab accounts, likewise mentioned Thoth as the Atlantean authority responsible for raising the Great Pyramid.

(See Cayce)

At-ia-Mu-ri

Site of impressive megalithic ruins in New Zealand, believed by John Macmillan

Brown, a leading academic authority of Pacific archaeology in the1920s, to be

evidence of builders from a sunken civilization. The name of the site is particularly

interesting for its combining of At[lantis] and Mu, at this midpoint between the

two sunken kingdoms.

(See Mu)

Atinach

The name by which the natives of Tenerife referred to themselves, it means

“People of the Sky-God.” Antinach derived from Atuaman, the Canary Island Atlas.

Atitlan

A lake in the Solola Department in the central highlands of southwestern

Guatemala, where Quiche-Maya Civilization reached its florescence. Atitlan was named after its volcano surrounded by lofty mountains, a setting that could

pass for a scene from Plato’s description of the island of Atlantis in Kritias.

Blackett describes Atitlan as “the large and rich capital, court of the native

kings of Quiche and the most sumptuous found by the Spaniards.” The lake’s

name was apparently chosen to match its appropriately Atlantean environment;

this, together with its obvious derivation from “Atlantis,” and the extraordinary

splendor of its culture, identify Atitlan foundation by Atlantean colonizers.

Atiu

An extinct volcano forming an atoll among the southern Cook Islands in the

southwest Pacific. “At,” associated with volcanic islands, occurs throughout the

Pacific Ocean.

Atius

Among the Pawnee Indians of North America, the sky-god, who controlled

and understood the movements of the sun, moon, and stars. The similarity of his

name and function to Atlas are affirmed by the Pawnee flood story.

Atjeh

A mountainous area of Indonesian Sumatra bordering a sloping plain reminiscent of Plato’s description of Atlantis. Even in this remote corner of the world,

“At” was anciently applied to sacred mountains.

Atl

“Water” in Nahuatl, the Aztecs’ spoken language. The ancient Mexican Atl

is likewise found in Atlantis, a water-born civilization. Atl also occurs on the

other side of the Atlantic Ocean among Morocco’s Taureg peoples, for whom it

also represents “water.” Atlantis’ former location between Mexico and Morocco

suggests a kindred implication between the Nahuatl and Taureg words.

In the Aztec calendar, “4-Atl” signifies the global deluge that destroyed a former

“Sun” or age, immediately after which the Feathered Serpent arrived with his

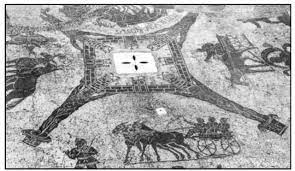

followers to found Mesoamerican civilization. The date 4-Atl is depicted on the

Aztec Calendar Stone as a celestial bucket of water inundating a half-sunken

stone pyramid, a self-evident reference to the final destruction of Atlantis.

(See Quetzalcoatl)

Atla

As described in the Hyndluljod Saga, she was a giantess, the mother of

Heimdall, an important Norse god. Atlantean elements evident in the mythic

relationship between Heimdall and Atla begin in the obvious derivation of her

name. She was also a “daughter of the ocean,” who gave birth to her divine son

“at the edge of the world, where land and sea meet.” So too, in Greek tradition,

the Pleiades were daughters of Atlas—“Atlantises”—whose sons founded new

civilizations. According to MacCullow (111), Atla personified at once the waves

of the deep and the “Heavenly Mountain,” Himinbjorg, from which Heimdall

derived his name, just as Atlantis was known after the sacred Mount Atlas. Even

in modern Norwegian, himinbjorg refers to a mountain sloping down to the sea.

Like the Mayas’ fair-skinned Itzamna, who brought civilization to Yucatan after a

great flood in the Atlantic Ocean, Heimdall was “the White God,” the father of

mankind.

Another Atla is a town in Mexico’s central plateau region, inhabited by the

Otomi Indians who preserve the mythic heritage of their Aztec ancestors beneath a

Christian gloss. Some Otomi tribes are among the most culturally conservative

peoples in Middle America, refusing to wear modern dress and still preserving

ritual kinship institutions handed down from pre-Spanish times. Because of this

maintenance of prehistoric traditions, anthropologists regard the Otomi as reliable

guides to Mesoamerica’s past.

Pertinent to our study is the Otomi acatlaxqui, the Dance of the Reed Throwers. Every November 25, 10 dancers assemble in Atla’s main square, dressed

in red and white cotton costumes, and wear conical headgear. From the points of

these paper hats stream red ribbons. Each dancer carries a 3-foot long reed staff

decorated with feathers and additional reeds attached. The performers form a

circle, at the center of which one of their number, dressed as a girl, rattles a gourd

containing the wooden image of a snake. The acatlaxqui climaxes when the surrounding dancers use their reeds to create a dome over the central character,

taken as a sign to begin a fireworks display.

The dance is not only deeply ancient, but a dramatic recreation of Otomi

origins. The 10 dancers symbolize the 10 kings of Atlantis, portrayed in their

conical hats streaming red ribbons, suggesting erupting volcanos. The reed was

synonymous for learning, because it was a writing instrument. The Aztecs claimed

their ancestors came to America from Aztlan, “the Isle of Reeds.” The boy “girl”

dancer at the center may signify the Sacred Androgyne, a god-concept featured

in an Atlantean mystery-cult. More likely, the female impersonator is meant to

represent Atlantis itself, which was feminine: “Daughter of Atlas.” His gourd

with the wooden snake inside for a rattle is a remnant of the same Atlantean

mystery-cult, in which serpent symbolism described the powers of regeneration

and the serpentine energy of the soul.

Forming a dome over the central performer may signify the central position

of Atlantis, to which all the allied kingdoms paid tribute, or it could represent the sinking of Atlantis-Aztlan beneath the sea, an interpretation underscored by the

fireworks timed to go off as the dome is created. The Otomi acatlaxqui-Atlantean

identity is lent special emphasis by the name of the town in which it is annually

danced, Atla. Moreover, November is generally accepted as the month in which

Atlantis was destroyed. The name, Otomi, likewise implies Atlantean origins: Atomi,

or Atoni, from the monotheistic solar god, Aton.

Atlahua

Aztec sea-god with apparent Atlantean provenance.

Atlaintika

In Euskara, the sunken island, sometimes referred to as “the Green Isle,”

from which Basque ancestors arrived in the Bay of Biscay. Atlaintika’s resemblance to Plato’s Atlantis is unmistakable.

(See Belesb-At)

Atlakvith

A 13th-century Scandinavian saga preserving and perpetuating oral traditions

going back 1,500 years before, to the late Bronze Age. Atlakvith (literally, “The

Punishment of Atla[ntis]”) poetically describes the Atlantean cataclysm in terms

of Norse myth, with special emphasis on the celestial role played by “warring comets”

in the catastrophe.

Atlamal

Like Atlakvith, this most appropriately titled Norse saga tells of the “Twilight

of the Gods,” or Ragnarok, the final destruction of the world order through

celestial conflagrations, war, and flood. Atlamal means, literally, “The Story of

Atla[ntis].”

Atlan

Today’s Alca, on the Gulf of Uraba, it was known as Atlan before the Spanish

Conquest. Another Venezuelan “Atlan” is a village in the virgin forests between

Orinoco and Apure. Its nearly extinct residents, the Paria Indians, preserve

traditions of a catastrophe that overwhelmed their home country, a prosperous

island in the Atlantic Ocean inhabited by a race of wealthy seafarers. Survivors

arrived on the shores of Venezuela, where they lived apart from the indigenous

natives. In Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs, “Atlan” meant, literally, “In

the Midst of the Sea.” Atlan’s philological derivation from Atlantis, kindred meaning, and common account of the lost island comprise valid evidence for

Atlanteans in Middle and South America, just where investigators would expect

to find important cultural clues.

Atland

The Northern European memory of Atlantis, as preserved in the medieval

account of a Frisian manuscript, the Oera Linda Bok, or “The Book of How Things

Were in the Old Days.”

(See Oera Linda Bok)

Atlanersa

King of Nubia in the fifth century B.C. The name means “Prince or Royal

Descendant (ersa) of Atlan,” presumably the Atlantis coincidentally described by

Plato in Athens at the same time this monarch ruled Egypt’s southern neighbor.

Unfortunately, nothing else is known about Atlanersa beyond his provocative

name, nor have any Atlantean traditions been associated with the little that is

known about Nubian beliefs.

Atlantean

As a pronoun, an inhabitant of the island of Atlas or its capital, Atlantis. As an

adjective, it defines anything belonging to the culture and society of the civilization

of Atlantis. In art and architecture, Atlantean describes an anthropomorphic

figure, usually a male statue, supporting a lintel often representing the sky. Until

the early 20th century, “Atlantean” was used to characterize the outstanding

monumentality of a particular structure, an echo of the splendid public building

projects associated with Atlantis.

Atlantean War

The Egyptian priest quoted in Plato’s Dialogue, Timaeus, reported that the

Atlanteans, at the zenith of their imperial power, inaugurated far-reaching military

campaigns throughout the Mediterranean World. They invaded western Italy and

North Africa to threaten Egypt, but were turned back by the Greeks, who stood

alone after the defeat of their allies. Successful counter offensives liberated all

occupied territories up to the Strait of Gibraltar, when a major seismic event

simultaneously destroyed the island of Atlantis and the pursuing Greek armies.

The reasons or causes for the war are not described.

The Egyptian priest implies that the Greeks perished in an earthquake on the

shores of North Africa (northern Morocco) fronting the enemy’s island capital. He

spoke of “the city which now is Athens” (author’s italics), meaning that the Greeks he described belonged to another city that preceded Athens at the same location

during pre-classical times. This represents an internal dating of the war to the late

Bronze Age (15th to 12th centuries B.C.) and the heyday of Mycenaean Greece.

There is abundant archaeological evidence for the Atlanteans’ far-ranging

aggression described by the Egyptian priest. Beginning in the mid-13th century

B.C., the Balearic Isles, Sardinia, Corsica, and western Italy were suddenly overrun

by helmeted warriors proficient in the use of superior bronze weapons technology.

At the same time, Libya was hit by legions of the same invaders described by the

Greek historian Herodotus (circa 500 B.C.) as the “Garamantes.” Meanwhile,

Pharaoh Merenptah was defending the Nile Delta against the Hanebu, or “Sea

Peoples.” His campaigns coincided with the Trojan War, in which the Achaeans

(Mycenaean Greeks) defeated the Anatolian kingdom of Ilios and all its allies.

Among them were 10,000 troops from Atlantis, led by General Memnon. These

widespread military events from the western Mediterranean to Egypt and Asia Minor

comprised the Atlantean War described in Timaeus.

It is possible, however, that Atlantean aggression was not entirely military but

more commercial in origin. Troy, while not a colony of Atlantis, was a blood related kingdom, and the Trojans dominated the economically strategic

Dardanelles, gateway to the Bosphorus and rich trading centers of the Black

Sea. It was their monopoly of this vital position that won them fabulous wealth. In

fact, it appears that the Atlanteans founded an important harbor city in western

coastal Anatolia just prior to the Trojan War (see Attaleia). But the change of

fortunes in Asia Minor also won them the animosity of the Greeks, who were

effectively cut off from the Dardanelles. This was the tense economic situation

that many scholars believe actually led to the Achaean invasion of Troy.

The abduction of Helen by Paris, if such an event were not merely a poetic

metaphor for the “piracy” of which the Trojans were accused, was the dramatic

incident that escalated international tensions into war—the last straw, as it were,

after years of growing animosity. Thus, the victorious Greeks portrayed the defeated Atlanteans as having embarked upon an unprovoked military conquest, when,

in reality, both opposing sides were engaged in economic rivalry, through Troy, for

control of the Bosphorus and its rich markets. These commercial causes appear

more credible than the otherwise unexplained military adventure supposedly

launched by the Atlanteans in a selfish conquest of the Mediterranean World, as

depicted in Timaeus. On the other hand, our pro-Atlantean example of historical

revision is at least partially undermined by the Atlanteans’ unquestionable aggression

against Egypt immediately after their defeat at Troy and again, 42 years later.

(See Memnon)

Atlanteotl

An Aztec (Zapotec) water-god who “was condemned to stand forever on the

edge of the world, bearing upon his shoulders the vault of the heavens” (Miller

and Rivera, 4). This deity is practically a mirror image in both name and function of Atlas-Atlantis, powerful evidence supporting a profound Atlantean influence

in Mesoamerica.

Atlantes

Described by many classical writers (Herodotus, Diodorus Siculus, etc.), a

people who resided on the northwestern shores of present-day Morocco. They

preserved a tradition of their ancestral origins in Atlantis, and appear to have

been absorbed by the eighth-century invasion of their land by the forces of Islam.

Notwithstanding their disappearance, their Atlantean legacy has been preserved

by the Tuaregs and Berbers, who pride themselves on their partial descent from

the Atlantes.

Atlanthropis mauritanicus

A genus name assigned by the French anthropologist, Camille Arambourg, to

Homo erectus finds at Ternifine, Algeria. It represented a slight development,

considered “superfluous” by some scholars, of a type along the Atlantic shores of

North Africa and may indicate that early man followed migrating animal herds across

former land bridges onto the island of Atlantis. There the abundance of game and

temperate climate fostered further evolutionary steps toward becoming Cro-Magnon.

The Atlanthropis mauritanicus hypothesis is bolstered by Cro-Magnon finds made

in some of the Canaries, the nearest islands to the suspected location of Atlantis.

Atlanthropis mauritanicus is also referred to as Homo erectus mauritanicus.

Atlantiades

Atlantises, Daughters of Atlas.

Atlantic Ocean

The sea that took its name from the land that once dominated it, Atlantis, just

as the Indian Ocean derived its name from India, the Irish Sea from Ireland, the

South China Sea from China, and so on.

Atlantica

A four-volume magnum opus by Swedish polymath Olaus Rudbeck. Published

in the year of his death, 1702, Atlantica was eagerly sought out by Sir Isaac Newton

and other leading 18th-century scientists. It describes “Fennoscandia,” roughly

equivalent to modern Sweden, as the post-deluge home of Atlantean survivors in

the mid-third millennium B.C.

(See Rudbeck)

La Atlantida

Literally “Atlantis”; an opera (sometimes performed in concert form) by Spain’s

foremost composer, Manuel de Falla (1876 to 1946). When a youth, de Falla heard

local folktales of Atlantis, and learned that some Andalusian nobility traced their

line of descent to Atlantean forebears. De Falla’s birthplace was Cadiz, site of the

Spanish realm of Gadeiros, the twin brother of Atlas and king mentioned in Plato’s

account (Kritias) of Atlantis.

La Atlantida describes the destruction of Atlantis from which Alcides (Hercules)

arrives in Iberia to found a new lineage through subsequent generations of Spanish

aristocracy. One of the opera’s most effective moments occurs immediately after

the sinking of Atlantis, when de Falla’s music eerily portrays a dark sea floating

with debris moving back and forth upon the waves, as a ghostly chorus intones,

“El Mort! El Mort! El Mort!” (“Death! Death! Death!”).

Atlantida is also the title of a Basque epic poem describing ancestral origins at

“the Green Isle” which sank into the sea.

Atlantika

In their thorough examination of the so-called “Aztec Calendar Stone,”

Jimenez and Graeber state that Atlantika means “we live by the sea,” in Nahuatl,

the Aztec language (67)

Atlantikos

Ancient Greek for “Atlantis,” the title of Solon’s unfinished epic, begun circa

470 B.C.

Atlantioi

“Of Atlantis.” The name appears in the writings of various classical writers

(Herodotus, Diodorus Siculus, etc.) to describe the contemporary inhabitants of

Atlantic coastal northwestern Africa.

Atlantis

Literally “Daughter of Atlas,” the chief city of the island of Atlas, and capital

of the Atlantean Empire. From the welter of accumulating evidence, a reasonable picture of the lost civilization is beginning to emerge: As Pangea, the original

supercontinent, was breaking apart about 200 million years ago, a continental mass

trailing dry-land territories to what is now Portugal and Morocco was left mid-ocean,

between the American and Eur-African continents pulled in opposite directions.

This action was caused by seafloor spreading, a process that moves the continents apart by the operation of convection currents in the mantle of our planet. The

resultant tear in the ocean bottom is the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, a seismic zone of

volcanic and magmatic activity extending like a narrow scar from the Arctic Circle

to the Antarctic. The geologic violence of the Ridge combined with rising sea

levels to eventually reduce the Atlantic island’s dry-land area.

About 1.5 million years ago, early man (Homo erectus mauritanicus, or

Atlanthropis mauritanicus) pursued animal herds across slim land bridges leading

from the western shores of North Africa onto the Atlantic island. These earliest

inhabitants found a natural environment of abundant game, extraordinarily fertile

volcanic soil with numerous freshwater springs, rich fishing, and a year-round

temperate climate. Such uniquely superior conditions combined to stimulate

human evolutionary growth toward the appearance of modern or Cro-Magnon man.

With increases in population fostered by the nurturing Atlantean environment,

social cooperation gradually developed to produce the earliest communities—

small alliances of families for mutual assistance. These communities continued to

expand, and in their growth, they became complex. The greater the number of

individuals involved, the greater the number and variety of needs became, as well

as technological innovations created by those needs, until a populous society of

arts, letters, sciences, and religious and political hierarchies eventually emerged.

The island of Atlas was, therefore, the birthplace of modern man and home of his

first civilization.

Time frames are very controversial among Atlantologists, and this issue is

addressed in the text that follows. Conservative investigators tend to regard

Atlantean civilization as having come into its own sometime after 4000 B.C. By the

end of that millennium, the Atlanteans were mining copper in the Upper Peninsula

of North America; establishing a sacred calendar in Middle America; building

megalithic structures such as New Grange in Ireland, Stonehenge in Britain, and

Hal Tarxian at Malta; as well as founding the first dynasties in Egypt and

Mesopotamia’s earliest city-states.

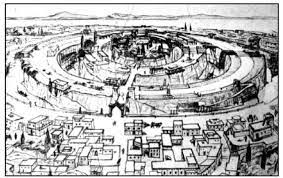

The island of Atlas was named after its chief mountain, a dormant volcano.

The chief city and imperial capital was Atlantis, arranged in alternating rings of

land and water interconnected by canals. High walls decorated with gleaming

sheets of polished copper alloys and precious stones, featuring regularly spaced

watchtowers, encircled the outer perimeter, which was separated from Mt. Atlas

on the north by a broad, fair plain. The inner rings were occupied by a spacious

racetrack, for popular events of all kinds; military headquarters and training

fields; a bureaucracy; the aristocracy; and the royal family, who resided in a

palace near the Temple of Poseidon, at the very center of the city. This temple

was the most sacred site in Atlantis—the place where holy tradition claimed

that the sea-god Poseidon mated with a mortal woman, Kleito, one of the native

inhabitants, to produce five sets of male twins. These sons became the first

Atlantean kings, from whom the various colonies of the Empire derived their

names. The first of these was Atlas, earliest ruler of the island in the new order

established by Poseidon.

By the 13th century B.C., the Atlantean Empire stretched from the Americas

to the western shores of North Africa, the British Isles, Iberia, and Italy, with

royal family and commercial ties as far as the Aegean coasts of Asia Minor. The

Atlanteans were responsible for and dominated the Bronze Age, during which

they rose to the zenith of their material and imperial success to become the

leading power of late pre-classical times. However, their expanding trade network eventually clashed with powerful Greek interests in the Aegean, resulting

in a long war that began at Troy and spread to Syria, the Nile Delta, and Libya,

climaxing at the western shores of North Africa.

Initially successful, the Atlantean invaders suffered defeats at the hands of

the Greeks, who had just pushed them out of the Mediterranean World when a

natural catastrophe destroyed the island of Atlantis, along with most of its population, after a day and night of geologic upheaval. The same event simultaneously

set off a major earthquake in present-day Morocco, where the pursuing Greek

armies had gathered, and engulfed them, as well. Atlantean survivors of the destruction arrived as culture-bearers in different parts of the world, founding new

civilizations in the Americas, and left related flood legends as part of the folk

traditions of peoples around the globe.

Atlantis: The Antediluvian World

The first modern, scientific examination of Atlantis begun in 1880 by

Ignatius Donnelly and published two years later by Harper Brothers (New York).

Certainly the most influential book on the subject, it triggered a popular and

controversial revival of interest in Atlantis that continues to the present day.

Donnelly’s use of comparative mythologies to argue on behalf of Atlantis-as-fact is encyclopedic, persuasive, and still represents a veritable gold mine of

information for researchers. His geology and oceanography were far ahead of his

time, while his conclusions were largely borne out by advances made during the

second half of the 20th century in the general acceptance of seafloor spreading

and plate tectonics. Atlantis: The Antediluvian World has been unfairly condemned

for its relatively few failings, mostly by Establishment dogmatists and cultural

isolationists to whom any serious suggestion of Atlantis is the worst heresy. But no

scholarly position has been able to remain unscathed after 100 years of scientific

progress, and, for the most part, Donnelly’s work has stood the test of time. In the

first 10 years after its publication, the book went through 24 editions, making it an

extraordinary best-seller, even by modern standards. It has since been translated

into dozens of languages, has sold millions of copies around the world, and is still

in print—all of which qualifies the book as a classic, just as vigorously condemned

and championed today as it was more than a century ago.

Atlantis: The Antediluvian World poses 13 fundamental positions, which formed

the basis of Atlantology. These predicate that:

1) Atlantis was a large island that lay just outside the Strait of Gibraltar in the

Atlantic Ocean.

2) Plato’s account of Atlantis is factual.

3) Atlantis was the site where mankind arose from barbarism to civilization.

Donnelly was the first to state this view, which, although not mentioned in Plato’s

Dialogues, is suggested by the weight of supportive evidence found in the traditions

of peoples residing within the former Atlantean sphere of influence.

4) The power of Atlantis stretched from Pacific coastal Peru and Yucatan in

the west to Africa, Europe, and Asia Minor in the east.

5) Atlantis represented “a universal memory of a great land, where early

mankind dwelt for ages in peace and happiness”—the original Garden of Eden.

6) The Greek, Phoenician, Hindu, and Scandinavian deities represented a

confused recollection in myth of the kings, queens, and heroes of Atlantis.

Although important Atlantean themes interpenetrate both Western and

Eastern mythologies, as he successfully demonstrated, Donnelly overstated that

relationship by reducing all the ancient divinities to merely mythic shadows of

mundane mortals.

7) The solar cults of ancient Egypt and Peru derived from the original

religion of Atlantis.

8) Egypt, whose civilization was a reproduction of Atlantis, was also the oldest

Atlantean colony.

Early Dynastic Egypt was a synthesis of indigenous Nilotic cultures and

Atlantean culture-bearers who arrived at the Nile Delta during the close of the

fourth millennium B.C. The hybrid civilization that emerged was never a “colony”

of Atlantis, although Donnelly was right in detecting numerous aspects of Atlantean

culture among the Egyptians.

9) The Atlanteans, responsible for the European Bronze Age, were the first

manufacturers of iron, as well.

While persuasive evidence for this last argument is scant, Donnelly’s identification of the Atlanteans with the bronze-barons of the Ancient World is among

his most valid and important positions.

10) The Phoenician and Mayan written languages derived from Atlantis.

Phoenician letters evolved from trade contacts with the Egyptians, whose

demotic script was simplified by merchants in Lebanon. If Egyptian and Mayan

hieroglyphs are both Atlantean, they should be at least partially intertranslatable,

which they are not. Even so, they may have evolved into separate systems over the

millennia from a shared parent source in Atlantis, because at least a few genuine

comparisons, known as cognates, between the two have been made.

11) Atlantis was the original homeland of both the Aryan and the Semitic peoples.

What later became known as the so-called “Indo-Europeans” may have first

arisen on the Atlantic island, and the Atlanteans were unquestionably Caucasoid.

But such origins are deeply prehistoric, and any real proof is very difficult to

ascertain. More likely, the Atlanteans were direct descendants of Cro-Magnon

types, whose genetic legacy has been traced to the original inhabitants of the

Canary Islands, the native Guanches, direct descendants of Atlantis. Donnelly

mistakenly accepted the Genesis story of the Great Flood and related references

in Old Testament and Talmudic literature as evidence for Aryan (Japhethic), as

well as Semitic origins in Atlantis. In truth, the Hebrews incorporated some

ancient Gentile traditions, such as the Deluge, into their own mosaic culture. Even

so, the Phoenicians were in part descended from the invading “Sea Peoples” of

lost Atlantis in the early 12th century B.C.

It was the depredations of these Atlantean survivors-turned-privateers that

ravaged the shores of Canaan, thereby making possible a takeover of the Promised

Land by the Hebrews. They intermarried with the piratical Gentiles to produce

the mercantile Phoenicians. Their concentric capital at Carthage and prodigious seafaring achievements were evidence of an Atlantean inheritance. These

influences, however, are after the fact (the destruction of Atlantis). Even so,

Edgar Cayce spoke of a “principle island at the time of the final destruction” he

called “Aryan.” Later, he described “the Aryan land” as Yucatan, where a yet to-be discovered Hall of Records contains original documents pertaining to

Atlantis.

12) Atlantis perished in a natural catastrophe that sank the entire island and

killed most of its inhabitants.

13) The relatively few survivors arrived in various parts of the world, where

their reports of the cataclysm grew to become the flood traditions of many

nations.

The late 19th-century publication of Atlantis: The Antediluvian World marked

the beginning of renewed interest in Atlantis, and is still among the best of its kind

on the subject.

(See Cayce)

Atlantis, the Lost Continent

A 1961 feature film by George Pal based less on Plato than the wildest statements of Edgar Cayce. Its bromidic screenplay, vapid dialogue, wooden acting,

and bargain-basement “special effects” have made Atlantis, the Lost Continent

into something of a cult classic for Atlantologists with a sense of humor.

Atlantis, the Lost Empire

Presented in a flat, dimensionless animation characteristic of the Disney

Studio since the death of its founder, this 2001 production has far less in common

with Plato than even George Pal’s unintentionally comic version. A sequel to

Atlantis, the Lost Empire, released two years later, was even more miserable, but

demonstrated that popular interest in the subject is still strong 24 centuries after

Plato’s account appeared for the first time.

Atlantology

The study of all aspects related to the civilization of Atlantis; also refers to a

large body of literature (an estimated 2,500 books and published papers) describing

Atlantis. It calls upon many related disciplines, including archaeology, archaeoastronomy, comparative mythology, genetics, anthropology, geology, volcanology,

oceanography, linguistics, nautical construction, navigation, and more.

Atlas

The central figure in the story of Atlantis, he was the chief monarch of the

Atlantean Empire, ruling from its island capital. Atlas was the founder of astrology-astronomy (there being made no original distinction between the two disciplines),

depicted as a bearded Titan or giant supporting the sphere of the heavens on his

shoulders, as he crouches on one knee. He thus became a symbol and national

emblem for the Atlanteans and their devotion to the celestial sciences. In Sanskrit,

atl means “to support or uphold.”

Parallel mythic descriptions of Atlas are revealing. His father, in the non Platonic version, was Iapatus, also a Titan, who was regarded as the father of

mankind. After his defeat by the Olympians, Iapatus was buried under a mountainous island to prevent his escape, suggesting the sunken island and punishment

meted out to Atlantis by the gods, as described in Plato’s account. Clymene was

the mother of Atlas. She was a sea-nymph who personified Asia Minor. Interestingly,

“Atlas” is the name of a mountain in Asia Minor (modern Turkey) near Catal Huyuk, which, at 9,000 years old, is among the most ancient cities on earth. Thus,

in Atlas’s parentage are represented the Far West of the Atlantic islands (Iapatus)

and the eastern extent of Atlantean influence (Anatolia) in Clymene. Her parents

were Tythys, “the Lovely Queen of the Sea,” and Oceanus, the oldest Titan, known

as the “Outer Sea,” or the Atlantic Ocean itself—all of which underscore Atlas’s oceanic identity, contrary to some scholars who confine him to Morocco and the

Atlas Mountains.

Plato’s version of Atlas’s descent makes Poseidon, the sea-god, his father,

and Kleito, the native girl of the ocean isle, his mother. These discrepancies are

unimportant, because the significance of myth does not lie in its consistency, but

in its power to describe. The Titan’s transformation into a mountain took place

after he fetched the Golden Apples for Heracles, who temporarily took Atlas’s

place in supporting the sky. He had been condemned to this singular position as

punishment for his leading role in the Titanomachy, an antediluvian struggle

between gods and giants for mastery of the world. But Perseus, Heracles’ companion, took pity on Atlas and turned him into a mountain of stone by showing

him the Gorgon Medusa’s severed head.

This largely Hellenistic myth from early classic or late pre-classic times

added peculiarly Greek elements, which clouded a far older tradition. Even so,

certain details of the original survive in the Titanomachy, the Atlanteans’ bid for

world conquest, of which the depredations of the so-called “Sea Peoples” against

Pharaoh Ramses III’s Egypt, Homer’s Iliad, and Plato’s Atlanto-Athenian War

were but various campaigns of the same conflict.

According to Sumerian scholar Neil Zimmerer, Atlas was indigenously known

in West Africa, where he was remembered as “the king of Atlantis, and fled when

the island sank into the sea. He established a new kingdom in Mauritania.”

Atlatonan

The “Daughter of Tlaloc,” a blue-robed virgin ritually drowned as a sacrifice

to the Aztec rain-god. Her fate and philological resemblance to Atlantis, literally,

“Daughter of Atlas,” are too remarkable for coincidence.

(See Tlaloc)

Atlcaulcaco

“The Waste of Waters,” a month in the Aztec calendar commemorating the

Great Flood, the first month calculated by the Aztec Calendar Stone, during which

a blue-robed virgin was ritually drowned to honor the rain-god. Plato described

the royalty of Atlantis as favoring blue robes during ceremonial events.

Atlixco

An Aztec outpost in south-central Mexico near a sacred volcano, Iztaccihuatl,

associated with the earlier Mayas’ version of Atlas, Itzamna, “the Lord of Heaven,”

and “the White Man.” Iztaccihuatl means “Great in the Water,” a clear reference

to Mt. Atlas, the great peak on the island of Atlantis.

Aton

Among the oldest deities worshiped in Egypt, he was the sun-god who alone

ruled the universe, suggesting an archaic form of monotheism, which may have

been the “Law of One” Edgar Cayce said functioned as a mystery cult in Atlantis

up until the final destruction. His “life-readings” described the Atlantean Followers

of the Law of One arriving in Egypt to reestablish themselves. Egyptian tradition

itself spoke of the Smsu-Hr, the Followers of Horus (the sun-god), highly civilized

seafarers, who landed at the Nile Delta to found the first dynasties. Shortly thereafter, Aton dwindled to insignificance, as polytheism rapidly spread throughout

the Nile Valley.

It was not until 1379 B.C., with the ascent of Amenhotep IV, who changed his

name to Akhenaton, that the old solar divinity was given primacy. All other deities

were banned, allowing Aton to have no other gods before him. The religious experiment was a disastrous failure and did not survive the heretical Pharaoh’s death

in 1362 B.C., when all the old gods were restored, except Aton. His possible worship

by Cayce’s Followers of the Law of One, along with the “At” perfix, suggest the

god was imported by late fourth-millennium B.C. Atlanteans arriving in Egypt. Aton’s

name appears to have meant “Mountain Sun City” (“On” being the Egyptian name

for the Greek Heliopolis, or City of the Sun-God), and may have originally referred

to a religious location (that is, Atlantis) rather than a god. Indeed, he was often

addressed as “The Aton,” the sun disc—a thing, more than a divine personality.

(See Cayce)

Aton-at-i-uh

The supreme sun-god of the Aztecs depicted at the center of their famous

“Calendar Stone,” actually an astrological device. His supremacy, astrological

function, and philological resemblance to the Egyptian Aton imply a credible connection through Atlantis. Additionally, young Egyptian initiates of the Aton cult were required to have their skulls artificially deformed after the example of their highpriest, Pharaoh Akhenaton, a practice that would identify them for the rest of their

lives as important worshippers of the Sun Disk. Surviving temple art from his city,

Akhetaton (current-day Tell el-Amarna), show the King’s own children with deformed

heads. On the other side of the world, the sun-worshipping elite among the Mayas

in Middle America and the pre-Inca peoples of South America all practiced skull

elongation. At both Akhetaton and Yucatan, the newborn infant of a royal family had

its head placed between cloth-covered boards, which were gently drawn together by

knotted cords. For about two years, the malleable skull was forced to develop into an

oblong shape that was considered the height of aristocratic fashion.

According to chronologer Neil Zimmerer, Aton-at-i-uh was originally a cruel

Atlantean despot who crushed a rebellion of miners by feeding them to wild beasts.

He was supposedly responsible for the destruction of Atlantis when he blew up

its mine shafts during his frustrated bid to assume absolute power. Aton-at-i-uh’s

reputation lived on long after his life, eventually transforming into the Aztec God

of Time, which destroys everything. As the sun was associated with the passage of

time, so Aton-at-i-uh personified both the supreme solar and temporal deity.

At-o-sis

A monstrous serpent that long ago encircled a water-girt palace of the gods

located across the Sunrise Sea, according to the Algonquian Passamaquoddy

Indians. Their concept is identical to the Egyptian Mehen, with its mythic portrayal

of Atlantis. Many tales of At-o-sis describe him as lying at the bottom of “the

Great Lake” (the Atlantic Ocean), with the remains of the gods’ sunken “lodge.”

Interestingly, the Passamaquoddy “Sunrise Sea” is in keeping with the Egyptian

sun-god, Ra, encircled by the Mehen serpent.

(See Atfih, Ataentsik)

At-otarho

Among the North American Iroquois, a mythic figure with a head of snakes

for hair, similar to the Greek Medusa, who was herself associated with Atlantis.

Atrakhasis

“Unsurpassed in Wisdom,” the title of Utnapishtim, survivor of the Great

Flood portrayed in the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh. Scholars believe the story

predates by 1,000 years its earliest written version, recorded around 2000 B.C. in

cuneiform script on 12 clay tablets. The prefix “At” combines with the epic’s early

third-millennium B.C. origins to indicate that Utnapishtim belonged to the First

Atlantean Deluge, in 3100 B.C.

Atri

In Hindu myth, one of 10 Prajapatis, beings intermediate between gods and

mortals, known as the progenitors of mankind, and assigned by Manu to create

civilization throughout the world. Atri may be an Indus Valley version of Atlas,

who likewise had nine brothers, Titans, who similarly occupied a position between

the Olympians and men. The Prajapatis were sometimes associated with the

Aditayas, the “upholders” of the heavens (sustainers of the cosmic order), just

like Atlas, who supported the sky. Atri’s prominent position as a world-civilizer

echoes the far-flung Atlantis Empire.

Atsilagigai

Literally, the “Red Fire Men” in Cherokee tradition. The name more broadly

interpreted means the “Men from the Place of Red Fire,” Cherokee ancestors.

Some of them escaped the judgement of heaven, when the Great Flood drowned

almost all living things. Atsilagigai refers to culture-bearers from a volcanic island,

and is a Native American rendering of the word “Atlantean.”

Atso, or Gyatso

Tibetan for “ocean,” associated with the most important spiritual position in

Boen-Buddhism, the Dalai Lama. The Mongolian word for ocean is dalai, a derivative of the Sanskrit atl for “upholder,” and is found throughout every Indo-European

language for “sea” or “valley in the water,” as though created by high waves: the

Sumerian Thallath, the Greek thalassa, the German Tal, the English dale, and so on.

Dalai, according to Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet, stems from the

Tibetan word for “ocean” that forms his name. Although Dalai Lama has sometimes

been translated as “Ocean of Wisdom,” it really means “Wise Man (Guru) of (or

from) the Ocean,” a title that appears to have originated with the pre-Buddhist Boen

religion somewhat absorbed by the creed introduced from India in the eighth century.

Atlantologists have speculated since the late 1800s that the history and religious

tenets of Atlantis are still preserved in some of Tibet’s secret libraries or even

encoded in the very ritual fabric of Tibetan religion itself. Some investigators

discern traces of the Atlantean mystery cults in Boen-Buddhism, particularly the

central importance placed on the doctrine of reincarnation and the sand mandalas

designed to portray the celestial city, with its concentric layout of alternating rings

of land and water powerfully reminiscent of Plato’s sunken capital, even to the

sacred numerals and elephants of Atlantis recurring through the sand-paintings.

These considerations seem stressed by Atlantean influences in the high-holy

terminology of Tibetan just discussed: Gyatso, Dalai, and so forth.

Edgar Cayce spoke of an unnamed person from the land now known as Tibet,

who visited Atlantis at a time when Atlantean teachings were being disseminated.

Perhaps this refers to the early spread of spiritual concepts to Tibet from Atlantis and accounts for the Tibetan “Wise Man from the Ocean.” In other “life-readings,”

Cayce mentions a “correlating” of Atlantean thought with Mongolian theology.

(Cayce, 957-1 M.53 3/12/30; 938-1 F.29 6/21/35; 1159-1 F.80 5/5/36)

Att

A word in the language of the ancient Egyptians signifying a large pool or

lake, a body of water. As elsewhere in Egyptian and the tongues of other peoples

impacted by the Atlantis experience, “Att” has an aquatic reference.

Attaleia

Modern Antalya, in western coastal Turkey, chief port of ancient Anatolian

Lycia, founded (actually refounded in classical times) by Attalos II of Pergamon,

circa 150 B.C. Recent excavations unearthed material evidence demonstrating

civilized habitation at Attaleia in the form of stone bulwarks and harbor facilities

dated to the late or early post-Bronze Age (circa 1300 to 900 B.C.) Attalus II

rebuilt the site, following closely the original walls, which were laid out in concentric

circles interspaced with watchtowers. Its architectural resemblance to Atlantis;

early date, during which Atlantis was at the zenith of its military influence, which

stretched as far as the eastern Mediterranean; identity as an Atlantis-like harbor

capital; and the Atlantean character of its name all suggest that Attaleia was

originally founded by Atlanteans in Asia Minor, perhaps to assist their Dardanian

allies in the Trojan War (1250 to 1240 B.C.)

Attawaugen

Known to native Algonquian speakers in Connecticut as a sacred hill associated

with the arrival of their forefathers on the eastern shores of North America

following a catastrophic flood that engulfed an ancestral homeland.

(See Atum)

Attewandeton

An extinct aboriginal tribe cited in the oral traditions of Upper Michigan’s

Menomonie Indians as responsible for having committed genocide against the

“Marine Men,” identified with Plato’s miners from Atlantis.

(See Bronze Age)

At-tit

In pre-Columbian Guatemala, an ancestral goddess who preached “worship

of the true God,” suggesting she was a practitioner (probably high priestess) of

the Followers of the Law of One, which Edgar Cayce claimed was the second most influential cult in Atlantis at the time of its final destruction. At-tit’s name

and character identify her as an important Atlantean visitor to Middle America.

(See Cayce)

Atu

In Sumerian myth, a sacred mountain in the Western Sea, from whence the

sky-goddess, Inanna, carried the Tablets of Civilization to Mesopotamia after Atu

was engulfed by the sea.

Atua

In Maori, “Altar of the God,” found among various Polynesian islanders. They

regard its memory as a sacred heirloom from their ancestors and a symbol of the

holy mountain, the original homeland of their ancestors who largely perished when

it sank beneath the surface of the ocean. Atua is also the name of a district in

Western Samoa, whose inhabitants speak the oldest language in Polynesia. The

cult of Atua, the chief god worshiped by the Easter Islanders, arrived after he

caused a great people to perish in some oceanic cataclysm.

Atuaman

Similar to the Polynesian Atua and the Egyptian Atum, Atuaman was the

most important deity worshiped by the Guanches, the original inhabitants of the

Canary Islands. His name means, literally, “Supporter of the Sky,” precisely

the same description accorded to Atlas. Atuaman is represented in pictographs,

especially at Gran Canaria, as a man supporting the heavens on his shoulders, the

identical characterization of Atlas in Western art. Among archaeological evidence

in the Canaries, the appearance of this unquestionably Atlantean figure—the

leading mythic personality of Atlantis—affirms the former existence of Atlantis

in its next-nearest neighboring islands.

Atuf

According to the Tanimbar Austronesian people of southeast Maluku, he

separated the Lesser Sundras from Borneo by wielding his spear, while traveling

eastward with his royal family from a huge natural cataclysm that annihilated their

distant homeland. It supposedly took place at a time when the whole Earth was

unstable. The chief cultural focus of the Tanimbar is concentrated on the story of

Atuf and his heroism in saving their ancestors from disaster. “Thereafter they had

to migrate ever eastward from island refuge to island refuge,” writes Oppenheimer,

and “as if to emphasize this, visitors will find huge symbolic stone boats as ritual

centres of the villages” (278). North of Maluku, a similar account is known to the

islanders of Ceram and Banda. In their version, their ancestors are led to safety by

Boi Ratan, a princess from the sunken kingdom.

Atum

Among the most ancient of Egyptian deities associated with a Sacred Mountain,

the origin of the first gods, Atum was the first divinity of creation. He created the

Celestial Waters from which arose the Primal Mound. Shu, the Egyptian Atlas,

declares in the Coffin Texts, “I am the son of Atum. Let him place me on his neck.”

In Hittite mythology, Kumarbi, a giant arising from the Western Ocean, placed

Upelluri on his mountainous neck, where he supported the sky, and is today regarded

by mythologists as the Anatolian version of Atlas.

Atum says elsewhere in the same Texts, “Let my son, Shu, be put beneath

my daughter, Nut [the starry night sky], to keep guard for me over the Heavenly

Supports, which exist in the twilight [the far west].” His position beneath Nut

indicates Shu’s identification with Atlas as the patron of astronomy. “The Heavenly

Supports” were known to Plato and his fellow Greeks as “the Pillars of Heracles,”

beyond which lay Atlantis-Atum.

The 60th Utterance of the Pyramid Texts reads, “Oh, Atum! When you came

into being you rose up as a high hill. You rose up in this your name of High Hill.”

As Clark explains:

When the deceased, impersonated by his statue, was crowned during the final ceremony inside the pyramid, he was invested with

the Red Crown of Lower Egypt. A heap of sand was put on the

floor and the statue placed upon it while a long prayer was recited, beginning, ‘Rise upon it, this land which came forth at Atum.

Rise high upon it, that your father may see you, that Ra may see

you.’ The sand represents the Primal Mound. The instruction to

the king is to ascend the mound and be greeted by the sun. This

implies that the mound can become the world mountain whereon

the king ascends to meet in his present form, the sun.

This, then, is the concept of kingship descended from the supreme sun-god,

Ra, on his holy mountain of Atum, the gods’ birthplace. It was this sacred ancestral

location, reported Egyptian tradition, that sank beneath the sea of the Distant

West, causing the migration of divinities and royalty to the Nile Delta. Atum’s

philological and mythic resemblance to Mount Atlas, wherein the Egyptian deity

is likewise synonymous for the sacred mountain and the god, defines him as a

religious representation of the original Atlantean homeland.

Atur

A unit of nautical measurement used by the ancient Egyptians that meant,

literally, “river” (more probably, an archaic term for “water”) and corresponded

to one hour of navigation covering 7,862.2 meters, equal to a constant speed of

about 4.5 miles per hour. The term was a legacy from the Egyptians’ seafaring

Atlantean forefathers, as is apparent in the prefix “at” and its definition as a

nautical term.

Atziluth

The Cabala, literally “the received tradition,” is a mystical interpretation of

Hebrew scriptures relying on their most ancient and original meanings. The

cabalistic term Atziluth refers to the first of four “worlds” or spiritual powers that

dominated the Earth. It signified the “World of Emanations” or “Will of God,”

the beginning of human spiritual consciousness. Philological and mythological

comparisons with Atlantis, where modern man and his first formalized religion

came into existence, appears preserved in the earliest traditions of the Cabala.

Autlan

Located in the foothills of the Sierra Madre Occidental Mountains, Autlan

was the home of the highly civilized Tarascans of Michoacan. The only

Mesoamericans known to have established regular trade with the civilizations of

coastal Peru, because of their seafaring abilities, the Tarascans’ superior bronze

weapons enabled them to fight off the Aztecs. Their chief ceremonial center was

at Tzintzuntzan, renowned for its outstanding Atlantean architectural features,

including circular pyramidal platforms profuse with the sacred numerals of Atlantis,

5 and 6, mentioned by Plato (in Kritias). Autlan’s philological resemblance to

“Atlantis” and the Atlantean features of the Bronze Age-like Tarascans define

both the site and its people as inheritors from the drowned island civilization.

Autochthon

Literally, “Sprung from the Land,” he was the sixth king of Atlantis listed in

Plato’s Kritias. Autochthon was also mentioned in Phoenician (Canaanite) myth—

the Sanchuniathon—as one of the Rephaim, or Titans, just as Plato described him.

The first-century B.C. Greek geographer Diodorus Siculus wrote of a native people

dwelling in coastal Mauretania (modern Morocco), facing the direction of Atlantis,

who called themselves the Autochthones. They were descendants of Atlantean

colonizers who established an allied kingdom on the Atlantic shores of North Africa.

According to the thorough Atlantologist Jalandris, “Autochthon” was a term by

which the Greeks knew the Pelasgians, or “Sea Peoples” associated with Atlantis.

Avalon

From the Old Welsh Ynys Avallach, or Avallenau, “The Isle of Apple Trees.”

The lost Druidic Books of Pheryllt and Writings of Pridian, both described as “more

ancient than the Flood,” celebrated the return of King Arthur from Ynys Avallach,

“where all the rest of mankind had been overwhelmed.” Avalon is clearly the

British version of Atlantis, with its grove of sacred apple trees tended by the

Hesperides, Daughters of Atlas (that is, Atlantises). Avallenau was also the name

of a Celtic goddess of orchards, reaffirming the Hesperides’ connection with Atlantis. Avalon was additionally referred to as Ynys-vitrius, the “Island of Glass

Towers,” an isle of the dead, formerly the site of a great kingdom in the Atlantic

Ocean. Avalon has since been associated with Glastonbury Tor—roughly, “Hill

of the Glass Tower”—a high hill in Somerset, England. During the Bronze Age,

the site was an island intersected by watercourses, resembling the concentric layout of the island of Atlantis. Underscoring this allusion is the spiral pathway that

spreads outward from the Tor, because Plato described Atlantis as having been

originally laid out in the pattern of a sacred spiral.

In Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Vita Merlini, Avalon is called “the Fortunate Isle,”

the same title Classical Greek and Roman writers assigned to Atlantic islands

generally and to Atlantis specifically. The Welsh Ynys Avallach and English

Ynys-vitrius were known along the Normandy coast as the Isle of Ys, which

disappeared beneath the waves. Avalon is also a town in Burgundy named after

the sunken island city, because some of its survivors reached Brittany.

(See Ablach, Ys)

Awun

One of the divine twins in the Chinese version of Atlantis.

(See Infoniwa)

Ayar-aucca

The third and last wave of foreign immigration into prehistoric South America

comprised refugees from a natural catastrophe—the sudden obliteration of their

once mighty kingdom in fire and flood. Appropriately remembered as the “War-like

People,” they were undoubtedly veterans of failed Atlantean wars in the eastern

Mediterranean and survivors from the final destruction of Atlantis, in 1198 B.C.

Their Atlantean identity is confirmed by the Incas themselves. They described the

Ayar-aucca as four twin giants who held up the sky. But they eventually grew tired

of their exertions on behalf of an ungrateful humanity, and let it fall into the sea,

creating a worldwide deluge that destroyed most of mankind.

One of the Ayar-aucca arrived in Cuzco, where he transformed himself into a

huaca, or sacred stone, but not before mating with a local woman to sire the first

Inca. Henceforward, Cuzco, known as “the Navel of the World,” was the capital of

the Inca Empire. The Ayar-aucca is the self-evident Peruvian rendering of the Bronze

Age Atlantis catastrophe, incorporated into the Incas’ imperial foundation myth.

(See Ahson-nutl, Navel of the World)

Ayar-chaki

This second wave of foreigners in South America suddenly appeared as

“Wanderers” or immigrants from earthquakes and floods that made continued residency at their distant homeland impossible. Their leader was Manco Capac

and his wife, Mama Ocllo. They established the “Flowering Age,” when the

“Master Craftsmen” built Tiahuanaco about 3,500 years ago. Indeed, radiocarbon testing at the ceremonial center yielded an early construction date of

+/-1600 B.C. (Childress, 139). Their sinful homeland was destroyed in a flood sent

as punishment from the gods, who spared Manco Capac and his large, virtuous

family. The Ayar-chaki were refugees from geologic violence that beset much

of the world with the return of a killer comet between 1600 and 1500 B.C., the

same celestial phenomenon that forced the earlier Ayar-manco-topa and the

later Ayar-aucca to flee their seismically unstable oceanic homelands for higher

ground.

Ayar-manco-topa

Bands of men and women who arrived along the northern coasts of Peru,

where they built the earliest cities, raised the first pyramids and other monumental structures, understood applied mathematics, cured illnesses with medicines

and surgery, and instituted all the cultural features for which Andean civilization

came to be known. In the Chimu version, they were led by King Naymlap, who

landed with his followers in “a fleet of big canoes.” The Ayar-manco-topa correspond to the Salavarry Period in Andean archaeology, when the first South

American pyramidal platforms with rectangular courts appeared in Peru. The

Ayar-manco-topa were probably Lemurian culture-bearers fleeing the worldwide

geologic upheavals that particularly afflicted, but did not yet destroy, their Pacific

Ocean homeland at the close of the fourth millennium B.C.

(See Lemuria)

Azaes

The ninth king of Atlantis listed in Plato’s Kritias. On the Atlantic shores of

Middle America, he was known as Itzamna, leader of the ancestral Mesoamericans’

“Greater Arrival,” that first wave of Atlantean culture-bearers from across the

Sunrise Sea, recorded by the Mayas. Portrayed as a fair-skinned, bearded figure

among the beardless natives, his title was “The First One.” He holds up the sky in

the temple art of Yucatan’s foremost Maya ceremonial center, Chichen Itza, which

was named after him and his descendants, the Itzas. Chichen Itza is particularly

noted for its Atlantean statuary and sculpted relief.

Azaes-Itzamna was probably a real colonizer from Atlantis, who established

his allied kingdom, which eventually took his name. In Yucatan, Azaes means “the

Parched or Thirsty One,” appropriate to the arid conditions of Middle America,

where sufficient drinking water was always a question of paramount importance

and the Atlantean Tlaloc was a rain-god of highest significance. Another title for

Itzamna was “Lizard,” the Mayas’ symbol for a bringer or harbinger of rain and,

hence, abundance.

Azores

Ten major islands in the North Atlantic comprising 902 square miles, lying

740 miles west of Portugal’s Cape Roca from the island of San Miguel. The Azores

are volcanic; their tallest mountain, Pico, at 7,713 feet, is dormant. Captain Diego

de Sevilha discovered the islands in 1427. Portugal’s possession ever since,

they are still collectively and officially recognized by Portuguese authorities

as “os vestigios dos Atlantida,” or “the remains of Atlantis.” The name “Azores”

supposedly derives from Portuguese for “hawks,” or Acores. The Hungarian

specialist in comparative linguistics, Dr. Vamos-Toth Bator, believes instead that

“Azores” is a corruption of “Azaes,” the monarch of an Atlantean kingdom, as

described in Plato’s account (Kritias).

None of the islands were inhabited at the time of their discovery, but a few

important artifacts were found on Santa Maria, where a cave concealed a stone

altar decorated with serpentine designs, and at Corvo, famous for a small cask of

Phoenician coins dated to the fifth century B.C.

The most dramatic find was an equestrian statue atop a mountain at San Miguel.

The 15-foot tall bronze masterpiece comprised a block pedestal bearing a badly

weathered inscription and surmounted by a magnificent horse, its rider stretching

forth a right arm and pointing out across the sea, toward the west. King John V

ordered the statue removed to Portugal, but his governor’s men botched the job,

when they accidentally dropped the colossus down the mountainside. Only the rider’s

head and one arm, together with the horse’s head and flank and an impression of

the pedestal’s inscription, were salvaged and sent on to the King.

These items were preserved in his royal palace, but scholars were unable to

effect a translation of the “archaic Latin,” as they thought the inscription might

have read. They were reasonably sure of deciphering a single word—“cates”—

although they could not determine its significance. If correctly transcribed, it might

be related to cati, which means, appropriately enough, “go that way,” in the language spoken by the Incas, Quechua. Cattigara is the name of a Peruvian city, as

indicated on a second-century A.D. Roman map, so a South American connection

with the mysterious San Miguel statue seems likely (Thompson 167–169). Cattigara

was probably Peru’s Cajamarca, a deeply ancient, pre-Inca site. Indeed, the two city

names are not even that dissimilar.

In 1755, however, all the artifacts taken from San Miguel were lost during a

great earthquake that destroyed 85 percent of Lisbon. While neither Santa

Maria’s altar in the cave nor San Miguel’s equestrian statue were certifiably

Atlantean, they unquestionably evidenced an ancient world occupation of the

Azores, and the bronze rider’s pointed gesture toward the west suggests more

distant voyages to the Americas. Roman accounts of islands nine days’ sail from

Lusitania (Portugal) describe contemporary sailing time to the Azores. The first century B.C. Greek geographer Diodorus Siculus reported that the Phoenicians

and Etruscans contested each other for control of Atlantic islands, which were

almost certainly the Azores. We recall Corvo’s Phoenician coins, while the

Etruscans were extraordinary bronze sculptors, who favored equestrian themes, such as the example at San Miguel. Both the Phoenicians and Etruscans were

outstanding seafarers.

Atlantologists speculate the Etruscans did not discover the islands, but learned

of them from their Atlantean fathers and grandfathers. The Azores’ lack of

human habitation at the time of their Portuguese discovery and their paucity of

civilized remains may be explained in terms of the Atlantis catastrophe itself, which

forced their evacuation and, over the subsequent course of centuries of geologic

activity, buried most of what survived under lava flows, which are common in the

islands. The oldest known reference to the Azores appears in Homer’s Odyssey,

where he refers (probably) to San Miguel as umbilicus maris, or “the Navel of the

Ocean,” the name of an Atlantean mystery cult.

(See Ampheres)

Aztecs

A Nahuatl-speaking people who established their capital, Tenochtitlan, at the

present location of Mexico City, in 1325 A.D. Over the next two centuries, they

rose through military aggression to become the dominant power in pre-Conquest

Middle America. Although their civilization was an inheritance from other

Mesoamerican cultures that preceded them, the Aztecs preserved abundant and

obvious references to Atlantis in their mythic traditions. Despite the millennia that

separated them from that mother civilization, their royal ancestry, though not

entirely unmixed with native blood, could still trace itself back to the arrival of

Quetzalcoatl, the “Feathered Serpent,” an Atlantean culture-bearer.

Aztecatl

The Aztecs themselves drew their national identity from this term, which

means, “Man of Watery (that is, sunken) Aztlan,” the Aztec name for Atlantis.

Aztlan

An island civilization in the Atlantic Ocean from which the ancestors of the

Aztecs arrived in America following a destructive flood. A clear reference to Atlantis,

Aztlan was remembered by the Aztecs as “the Field of Reeds,” “Land of Cranes”

(denoting its island character), and “the White Island.” On the other side of the

world, the ancient Egyptians referred to an island in the Atlantic Ocean from

which the first gods and men arrived at the Nile Delta as Sekhet-aaru, or “the

Field of Reeds.” To both the Aztecs and the Egyptians, reeds were symbolic for

wisdom, because they were used as writing utensils. Atlantis was likewise known

as “the White Island” to North African Berbers, ancient Britons, and Hindus of

the Indian subcontinent.

(See Albion, Atala)

B

Bacab

A Mayan name given to anthropomorphic figures usually carved in relief

on sacred buildings. They simultaneously represent a single god and his own

manifestation as twin pairs signifying the four cardinal directions. The Bacabs

are portrayed as men with long beards, distinctly un-Indian facial features, and

wearing conch shells, while supporting the sky with upraised hands. Their most

famous appearance occurs at a shrine atop Chichen Itza’s Pyramid of the Kukulcan,

the Feathered Serpent, in Yucatan. Placement in the holy-of-holies at this structure

is most appropriate, because the Mayas venerated Kukulcan as their founding

father—a white-skinned, yellow-bearded man who arrived from over the Atlantic

Ocean on the shores of prehistoric Mexico with all the arts of civilization. Bacab is

synonymous with Kukulcan and undoubtedly a representation of Atlas in Yucatan.

Indeed, the conch shell worn by the Chichen Itza Bacabs was the Feathered

Serpent’s personal emblem, symbolic of his oceanic origins.

Plato tells us that sets of royal twins ruled the Atlantean Empire, which was

at the center of the world. So too, the Bacabs are twins personifying the sacred

center. Among the many gifts they brought to the natives of Middle America was

the science of honey production, and even today they are revered as the divine

patrons of beekeeping. In ancient Hindu tradition, the first apiarists in India were

sacred twins called the Acvins, redoubtable sailors from across the sea. Each brother

Bacab presided over one year in a four-year cycle, because Bacab was the deity of astrological time. In Greek myth, Atlas, too, was the inventor and deity of

astrology-astronomy.

Mexican archaeologists have associated the post-Deluge arrival of the Bacabs

in Guatemala with the foundation date of the Mayas and the start of their calendar:

August 10, 3113 B.C. This date finds remarkable correspondence in Egypt, where

the First Dynasty suddenly began around 3100 B.C. after gods and men were said

to have sailed to the Nile Delta when their sacred mound in the Distant West

began to sink beneath the sea. The Babylonian version of the Great Flood that

produced Oannes, the culture-bearer of Mesopotamian civilization, was believed

to have taken place in 3116 B.C. Clearly, these common dates commemorated by

disparate peoples define a shared, seminal experience that can only belong to

Atlantis.

Bahr Atala

Literally, the “Sea of Atlas,” a south Tunisian archaeological site known as

Shott el Jerid. With concentric walls enclosing what appears to be a centralized

palace, it resembles the citadel of Atlantis, as described by Plato. Nearby hills are

locally referred to as the Mountains of Talae, or “the Great Atlantean Water.”

Bahr Atala was probably an Atlantean outpost in Tunis during the Late Bronze

Age, from the 16th to 13th centuries B.C.

NEXT 66S

Balam-Qitze

FAIR USE NOTICE

This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a journalist, I am making such material available in my efforts to advance understanding of artistic, cultural, historic, religious and political issues. I believe this constitutes a 'fair use' of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law.

In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. Copyrighted material can be removed on the request of the owner.

No comments:

Post a Comment