The Saturn Myth

A reinterpretation of rites and symbols illuminating

some of the dark corners of primordial society

By David Talbott III:

V:

The Holy Land

Ancient ritual the world over conceived the terrestrial ruler as the incarnation of the Universal

Monarch. By the same principle each local city or kingdom became a transcript of the god-king’s

primeval domain. The sanctified territory on earth was laid out according to a cosmic plan, revealed

in remote times.

On this priority of the cosmic dwelling all major traditions concur. A celestial Sumer and Akkad

preceded the organization of the actual Mesopotamian kingdoms. And such settlements as Eridu,

Erech, Babylon, and Lagash took their names from a heavenly city occupied by the central sun.

Every Egyptian town—Heliopolis, Herakleopolis, Memphis, Abydos, Thebes, Hermopolis—mirrored a prototype, a “city in which the sun shone forth in the beginning.” So did Egypt as a whole,

according to the ritual, reproduce the dwelling gathered together and unified by the creator.

Hebrew tradition knew a heavenly Jerusalem which gave its name to the terrestrial city; and what the

Hebrews claimed of their city, the Muslims claimed of Mecca. The Chinese declared their kingdom to

be a copy of the celestial empire, and each capital city imitated the same plan.

In unison, diverse traditions of the Near East, Europe, Asia, and the Americas recall a Holy Land par

excellence, founded and ruled by the creator himself. From this Saturnian kingdom every nation took

instruction in the ideals of kingship and in the proper organization of the sacred domain.

The Mother Land

In the creation myth the great god raised a circular plot of “earth” from the cosmic waters. The

enclosure was Saturn’s paradise—the kingdom of heaven—appearing as a vast wheel or throne

turning about the stationary god.

Saturn’s Earth[417]

In seeming reference to the fertile soil around us, the Latin poet Virgil celebrates the “mother of

harvests” and “the mighty mother of men.” But he gives the great goddess of fertility an intriguing

title: “Saturn’s Earth.”

Why Saturn’s Earth? The curiosity increases when one notices that the Sumerian An, Enki, and

Ninurta—all identified as Saturn—rule “in the Ekur.” The translators render Ekur as “earth.”[418]

So also did Chinese astronomy deem Saturn the planet of the “earth,”[419] while the Phoenician

Saturn is said to have dwelt “in the centre of the earth.”

The Egyptian “earth god” is Seb (or Geb). That is, writes Budge, “the earth formed his body and was

called the ‘house of Seb.’”[420] But if Seb’s body was the earth, why did the Greek historian

Plutarch translate Seb as Kronos (Saturn)?[421]

What connection of the planet Saturn and the “earth” might have justified this identity? Of course the

common English translation, “earth,” naturally suggests to the modern mind our planet suspended in

space. But to the ancients no such detached view was possible. They knew only a terrestrial region,

however large or small. In archaic ritual, the terms which experts translate as “earth” mean literally

“land,” “place,” “province”; and the only region which the ancients considered worthy of

sanctification as the “land” was their own unified state or nation—all else belonging to the

“barbarians.”

But every sacred “land” organized around a religious-political centre proclaimed itself a copy of the

primeval dwelling in heaven. Thus the Egyptian ta, often rendered as “earth,” refers first and

foremost to the heavenly province of the creator—the ta ab (“pure land”), ta nefer (“beautiful land”),

ta sheta (“mysterious land”), ta ankhtet (“land of life”), or ta ur (“great land”). Such terms are

synonymous with ta Tuat, the “land of the Tuat,” the cosmic dwelling of Osiris or Re. In naming

terrestrial Egypt ta, the Egyptians gave their homeland the name of the cosmic “place” par

excellence.

Ta signifies the cosmic dwelling “gathered together” by the creator. That the Egyptians conceived the

ta as the “body of Seb” corresponds with everything we have learned of the primeval enclosure. Of

equal significance is Seb’s hieroglyphic symbol, the egg . The myths say that the egg of Seb is

that from which the sun first shone forth (i.e., it is the same as the revolving egg of Atum, the egg of

the Cosmos). This so-called “world egg” has no connection with our planet.

Nor did the Sumerian Ekur, “earth,” denote our planet. As observed by Jensen, Langdon, and others,

the Ekur appears as the celestial home of the creator.[422] Åke Sjöberg and E. Bergmann state the

identity bluntly.[423] The Sumerians knew this celestial domain as the ki—“the place” or “the

land”—invoked as ki-sikil-la, the “pure land” or “pure place,” and ki-gal, “great land.”[424]

The Sumerian ki was the Assyrian Esara, the supreme “place.” Rather than familiar geography, the

term refers to the created land of cosmic beginnings. Thus Esara, according to Jensen, was used with

special reference to “the earth as it appeared at the creation.”[425] Equivalent is the “celestial land”

of Hindu myth,[426] or the “pure land” of the Buddhists.[427] No greater mistake could be made than

to seek a geographical location of this lost land.

Ancient cosmology locates the primordial “place,” not “down here,” but at the celestial pole, the

centre and summit. In Egyptian thought, states Clark, the celestial pole is “that place” or “the great

city.” Here dwells the “Master of the Primeval Place.”[428] When the god in the Coffin Texts

proclaims, “I am the creator who sits in the supreme place,” the reference is to the polar abode, Clark

tells us.[429] Iranian astronomy drew on the same tradition when it designated the celestial pole as

Gah, which means simply “the place,” the dwelling of “the Great One in the Middle of the Sky.”[430]

In Iranian cosmology it is Saturn who occupies the polar Gah, “place”—just as it is Saturn who, in

the form of the polar An, rules the Sumerian “pure place.” Hence, one could properly call this domain

“Saturn’s Land,” or “Saturn’s Province.” And this simple relationship enables us to understand why

the ancients, who regarded their own sacred territory as a duplication of the celestial dwelling,

extolled the fertile soil as “Saturn’s Earth.”

The Egyptian Paradise

A clarification of the Egyptian concept will help to illuminate the general tradition. One of the

features of the Egyptian ta, “land,” which has encouraged its identification with our earth is its

mythical character as a garden or field of abundance. To reside in the ta is to live in the Garden of

Hetep. Many descriptions of this primeval domain do indeed sound very much like a terrestrial

paradise. The land is filled with wheat or barley, and the inhabitants drink of beer and cool waters. In

the Book of the Dead, the deceased king announces, “I know the names of the domains, the districts

and the streams within the Garden of Hetep . . . there is given to me the abundance . . .”[431] The

Pyramid Texts depict the deceased king drinking oil and wine and living off “the bread of eternity”

and “the beer of everlastingness.”[432]

The Egyptians deemed the meadow of peace and plenty at once the ancestral land and the future

home of those yet to pass beyond. Many writers, of course, recognize the Garden of Hetep as an early

—perhaps the earliest—mythical expression of the lost paradise. Its underlying nature, however, has

yet to be penetrated by the conventional schools.

To anyone willing to consider the entire context of Egyptian evidence, it should be clear that the

primeval land produced by the creator and imbued with overflowing abundance was celestial. Those

who attain the Garden of Hetep reach the heaven of the creator. The deceased king in the Pyramid

Texts goes “to see his father Osiris.” He announces: “I have gone to the great island in the midst of the

Sekhtet Hetepet [Garden of Hetepet] on which the swallow-gods alight; the swallows are the

Imperishable Stars . . . I will eat of what you eat. I will drink of what you drink, and you will give

satiety to me at the pole . . . You shall set me to be a magistrate among the Khu, the Imperishable Stars

in the north of the sky, who rule over offerings and protect the reaped corn, who cause this to go down

to the chiefest of the food-spirits who are in the sky.”[433]

Let us analyze this important text, which combines several Egyptian interpretations of the celestial

garden. As used above, the term Hetepet signifies “abundance” or “food offerings.” so that the

Garden of Hetepet is the Garden of Abundance or Garden of Food Offerings in heaven. Hetepet

possesses a root sense of “gathering together” or “uniting” (much like temt, “collecting,” “gathering

together”), a meaning which is vital to the symbolism as a whole.

Hetepet is, of course, inseparable from hetep, “rest,” “standing in one place.” The Garden of Hetepet

is the Garden of Hetep. One can reasonably speak of the Garden as the dwelling of rest and

abundance (i.e., “peace and plenty”), gathered together by the creator. The symbolism is, as I shall

attempt to show, much deeper than standard interpretations would suggest.

In the midst of the celestial garden is the “great island,” whose inhabitants—the swallow-gods—are

the Akhemu-Seku (“never-corrupting” ones), here translated as “the Imperishable Stars.” The

Egyptians also called these divinities Akhemu-Urtu (“never-resting” ones), conventionally identified

as circumpolar stars who, revolving around the polar axis, never sink beneath the horizon. But the

foregoing text identifies these gods as more than “stars” (in the modern sense of the word). They are

the Khu (“words of power” or “light spirits”), which erupted directly from the creator. There is a

vast body of evidence to show that these secondary light gods were themselves the abundant

“food” or “offerings” of the celestial garden and that this is what the above hymn means when it

speaks of the “food-spirits.”

The flowing beer (or wine) and the field of grain (wheat, barley, corn) are, in fact, indistinguishable

from the primeval sea of words (secondary gods) which sprang from the creator and which the great

god gathered together to form the enclosure of the primeval island—his own “body.” On the “great

island in the midst of the Garden of Hetepet” the fiery particles (Khu, Akhemu-Urtu) “alighted,”

collectively forming the enclosure. If, in one myth, the god’s shining “words” congealed into the

island, in another, the isle was produced from the luminous “grain of heaven.” The “words of power,”

the “grain,” and the “company of the gods” represented interrelated mythical interpretations of the

primeval matter ejected by the creator. In the imagination of the Egyptians the creator collected the

grain from the celestial field (sometimes called the Sekhet-Sasa or “Field of Fire”), and produced the

enclosure as the “granary of the gods”—the house of abundance which every king hoped to attain

upon death. The grain served as the “dough” from which the creator fashioned his dwelling; and it is

this crucial relationship which explains the interconnected meanings of the Egyptian term paut or

pautti—signifying at once the “primeval matter” (company of gods) and “dough” or “bread.” The

creator organized the company of gods (the grain) into the revolving Cosmos, conceived as a celestial

land of abundance.

Primeval matter=creative “words”

=secondary gods=grain of heaven (dough, bread).

In their ceremonies the Egyptians reenacted the creation on a microcosmic scale by fashioning ritual

dough cakes used in offerings to the dead. These cakes of paut symbolized the created “land” or

“earth,” produced from the overflowing grain of heaven. Thus, while the Egyptian ta means “land,” ta

also means “bread” or “cakes.” Such interrelated terminology pervades the Egyptian language. A

review of this usage reveals two consistent principles:

1. The lesser gods (children, servants, assistants) coincide with the “dough”—the beer and grain

which erupted from the creator. (Prior to unification as the “land,” or Cosmos, the fiery particles

compose the sea of Chaos and thus may be termed “fiends” or “demons” of darkness.)

2. The organized dwelling (“land,” “city,” “place,” “domain”) coincides with the “granary” and the

molded “cake” or “bread” of heaven.

Here are a few of the many examples:

The “children” of the great god are the pert, “things which appear”; but pert also means “grain.” The

texts describe the beer and grain (the children) as pert er kheru, “appearing at [or as] the words” of

the creator. Thus, while akhib means “to speak,” akhabu signifies “grain,” and the inhabitants of the

heavenly dwelling are the Akhabiu.

Similarly, seru means at once “grain” and “princes” or “chiefs”; both uses are inseparable from ser,

“to command,” and serui, “flame.” Properly understood the “grain” and the “princes” refer to the

same fiery material mythically perceived as the creator’s flaming “commands.”

Though heq signifies the “ale” or “beer” spit out by the creator, it also means “to command.”

If aut is “radiance” or “glory” (compare khu), the same word signifies “abundance.” But aut derives

from au, “children.” The abundant wheat and barley—i.e., the light spirits who glorify the creator—are brought forth as the god’s own offspring.

Henu means the “servants” of the great god, who “go round about” (hennui); but henu also denotes

“abundance.” The lush growth of the celestial abode is the hen, but the same word signifies the

“glory” or “majesty” of the ruling divinity. From the notion that the celestial lights “glorify” the

creator, it is a very short step to the idea that they “praise” him or “sing prayers” to him. Thus hen

means also “to praise.”

Accordingly, the word tebhu means “abundance” but also “prayers.” (One should not attempt to

distinguish the “prayers” from the praying gods; those who glorify the great god are the glory.)

So also does senem mean, at once, “abundance” and “to pray,” “adore.”

While “grain” is shert, the related term sherriu signifies the “little gods.”

Fenkhu means “abundance,” but the same word denotes the inhabitants of the celestial land.

Ahau means “food” but also the dwellers in the “land.”

Hetepet means “abundance,” while the hetepetiu are the secondary gods. Khefa is “food,” but the

Kheftiu are the “fiends” of Chaos (eventually organized into the unified dwelling).

Betu means the “grain” or “barley” of heaven, but also the “demons.”

Just as the secondary gods compose the “limbs” or “members” of the central sun, so does the grain.

An Egyptian term for “grain” is atpet, manifestly derived from at, “limb,” and pet, “heaven.” The

grain becomes the “limbs of heaven” (or of the Heaven Man).

Thus nepu signifies “limb” or “flesh,” while neper means “grain.” The primeval abode is Nepert,

i.e., the land formed from the grain.

Gathered together by the creator, the grain becomes the enclosure of the primeval land—the

“granary” or the “bread” of the gods (symbolized by the dough cakes employed in the rites of the

dead). Thus, while shen ( , ) denotes the “bond” or “cord” in which the great god dwells, shena

means at once “granary” and “body” (the god’s body encompasses the grain). Shenti also means

“granary,” but the same word signifies “garment.” (The garment—belt, girdle, collar—is the

organized band of grain.) Symbolizing this celestial enclosure are the shens, or sacrificial cakes.

Peq is a name of the celestial land; and the great god’s garment (=land) is peqt. But peqt also means

the “cake” of the gods.

Similarly, sesher is the god’s garment, while seshert denotes the cake or bread of heaven.

Qefenu is a name of the god’s dwelling, while qefen signifies the sacred “cake.”

Nes means both “grain” and “fire.” (The field of grain is the field of fire.) In the rites the grain is

fashioned into the nest or sacrificial cake. But nest also denotes the “throne” of the creator.

(Creator’s throne=primeval land.)

The benet are light-spirits who accompany the creator. Helping to explain the term is the related

word bennut, signifying the “matter” or “fluid” which erupted from the solitary god. This primeval

matter forms the sacred cake, for “cake” or “bread” is bennu. Bener, a name of the created land,

derives from the same root.

The “food-spirits” gathered together to form the primeval enclosure are the “builders” of the god’s

home. Thus, the “beer” which flows from the creator is aqet, but aqet also denotes a “builder” or

“mason”—i.e., one of the aqetu who fashion the celestial dwelling.

The language repeats the same connections again and again:

1. Secondary light gods=celestial abundance (grain, beer, etc.)

2. Unified dwelling of god=celestial abundance (grain, land, body, garment, beer, etc.) gathered into

organized form, i.e., as “cake” or “bread.”

It is clear that, in Egyptian ritual, the sacred cakes meant much more than mere “bread.” The cakes

were symbols of the great god and his creation—the Garden of Abundance. The celestial prototype of

the cake was the island of beginnings, which the creator organized from a previously chaotic sea of

“beer and grain.” That the Egyptians conceived the unified “land” or celestial “bread” as the body of

the creator is crucial to the symbolism; in eating the cake, or in drinking the sanctified beer, the

initiates symbolically enjoyed the abundance of the primeval age, or, what is the same thing, they

consumed the body of the creator. (I shall not distract from the present discussion by elaborating

parallels in later religious symbolism.)

The interrelated terminology identifies the primeval ta, “land,” with the enclosure of the central sun

. The Egyptians knew that the primeval garden lay within the circle of the Aten. (“Thou makest thy

creations in thy great Aten,” reads the Litany of Re.)[434] Thus the Egyptians denoted the garden of

Re by combining the Aten glyph with the glyph for “garden”: .

The significance of such imagery seems to have escaped mythologists: the lost “homeland” of global

lore was the original dwelling of the sun-god. Of the Egyptian han or “homeland,” Reymond writes:

“The Sun-God was believed to operate from his birthplace . . . In its essential nature the primeval

sacred domain was the very place from which the Radiance issued first.”[435] This “sacred domain”

was the island of ta, the celestial earth.

Egyptian sources term the created domain Neter-ta—the “Holy Land” or “God’s Earth.” Here

occurred the primordial dawn. That is, it was from Neter-ta that the stationary sun shone forth. A

hymn to Amen-Re, for example, invokes the sun-god as the “Beautiful Face, who comest [shines]

from Neter-ta.”[436] No wonder that Egyptologists confuse this Holy Land with the terrestrial east—the place of the solar sunrise!

The exact counterpart of the Egyptian Neter-ta is the Sumerian Dilmun, the “clear and radiant”

dwelling of the gods, ruled by the Universal Monarch Enki. Dilmun, according to Sumerian hymns, is

“the place where the sun rises.”[437] And many thousands of miles from Mesopotamia the natives of

Hawaii recall an ancestral land, Tahiti Na, “our peaceful motherland: the tranquil land of

Dawn.”[438] So also did the Hindus, Persians, Chinese, and many American Indian tribes conceive

the lost paradise as the place of the “sunrise.”[439]

The World Wheel

That Saturn, the primeval sun, first shed its light from the circle of the created “earth” will explain

why the celestial land often appears as a great wheel revolving around the stationary sun. It may be

called alternately the “world wheel,” “world mill,” or “chariot.” And this turning wheel of the Holy

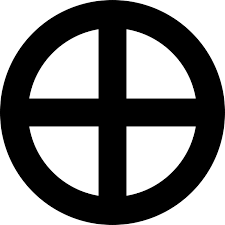

Land is consistently represented by the signs and

Hindu descriptions of the cosmic wheel affirm that the ancient sun stands at the centre, as the

Chakravartin or “wheel-turner.” From the stationary pivot of the wheel, the Universal Monarch

“directs the movement without participating in it himself,” states Guenon.[440]

On the Buddhist iconography of the world wheel, Coomaraswamy writes: “He whose seat is on the

lotiform nave or navel of the wheel, and himself unmoving sets and keeps it spinning, is the ruler of

the world, of all that is natured and extended in the middle region, between the essential nave and the

natural felly.”[441] The organized “world” lies within the ever-turning rim . The Buddhists

regard this sacred domain as both an ancestral paradise and “the situation of the Goal,”[442] the

heaven reached by the deceased.

Buddhist myths say that a plot of “land” congealed out of the cosmic waters to form a band around the

great father, becoming the “golden wheel”: “The surface of these waters, just as in the Brahmanical

cosmology and in Genesis, is stirred by the dawn wind of creation. The foam of the waters solidifies

to form the golden circle (Kancana-mandala) or ‘Land of Gold’ (Kancana-bhumi), the same as

Hsuan-tsang’s ‘golden wheel’ and representing ‘the foundations of the earth’ . . . The surface of the

Land of Gold is the Round of the World.”[443]

That the world wheel stood at the stationary pole is confirmed by the Buddhist account of the

primeval “wheel king”—owner of a “wheel whose steadfastness was the measure of his fitness to

rule.” He was “a universal king,” “a righteous king ruling in righteousness, lord of the four quarters

of the earth.” (The four quarters were the four divisions of the wheel .) The myth states not only

that the revolving wheel remained in a stationary position, but that a fall from its fixed place would

mean the death of the ruler. “If the Celestial Wheel of a Wheel-turning king shall sink down, shall slip

down from its place, that king has not much time to live . . .”[444] That is, of course, exactly what

happened: the wheel fell, the Universal Monarch died, and the world was thrown into confusion.

One is reminded of the Zoroastrian world wheel called the Spihr. This ever-turning wheel was the

“body” of Zurvan, or Time, the planet Saturn. Throughout the primordial epoch, the wheel of the Spihr

remained in one spot; and its fall coincided with the collapse of the prosperous age.[445]

In many myths Saturn’s earth-wheel acquires the poetic form of an enormous mill churning out

abundance. An old Icelandic tradition, for example, knew the mill as the fabulous possession of

Amlodhior Frodhi under whose rule mankind enjoyed peace and prosperity. Recruited by Frodhi to

work the mill were two giant maidens, who day and night turned the massive wheel, grinding out gold

and happiness. But like all fabled wheels, Frodhi’s mill eventually broke down, causing the death of

the great monarch.

As shown by de Santillana and von Dechend, Frodhi was the planet Saturn.[446] The authors (whose

work is titled Hamlet’s Mill) review widespread traditions of the cosmic mill—from Iceland to

Finland to India to Greece—finding many unexpected connections with the same remote planet. (Not

once, however, do the two writers wonder whether the tradition of the Saturnian wheel may have

originated in the actual observation of a band around the planet.)

As the possession of the Universal Monarch, the mill lies in the farthest north and is regularly

identified with the “pole” or “axis” of the world. The Finnish Kalevala locates the mill (here called

the Sampo) on a great rock in “North Farm,” the polar garden of plenty. The hero Ilmarinen:

. . .

forged the Sampo skillfully: on one side a grain mill, on the second side a salt mill, in the third

a money [i.e., gold] mill.

Then the Sampo ground away, the lid of many colours went round and round.[447]

This cosmic mill, too, broke down, bringing wholesale disorder. And if the Finnish Sampo is a late

and fanciful version of the mill, the linguists now recognize the Sampo’s connection with the older

skambha of Hindu ritual.[448] In the Atharva Veda the Skambha (meaning “pole”) appears as the

“golden embryo” and the “frame of creation,” a mill-like edifice “which poured forth the gold within

the world.” The Vedic hymn equates the mill (Skambha) with the whole creation. The body of the

Skambha houses the life elements and the gods; it is the “ancient one” or “great monster,” whose

veins are the four quarters of the world (i.e., ). That the cosmic mill is at once the Universal

Monarch’s body and the created paradise will immediately explain why, in the general tradition, the

collapse of the great wheel coincides with the death of the god-king and the sinking of the lost land

into the waters of the Abyss.

Nothing so confuses the underlying theme as the habit, begun long ago, of conceiving the primordial

wheel, or island of “earth,” in terrestrial terms. Could the landscape familiar to the ancients have

produced the many interrelated images of the turning wheel?

The One-Wheeled Chariot

The great god sits enthroned within the celestial earth as in a one-wheeled chariot. Thus, in

Scandinavian rock carvings the symbol —the universal sign of the world wheel—may either

appear alone or as the wheel of a celestial wagon. All ancient sun-gods seem to own such a wheel or

chariot. The one-wheeled chariot of the Hindu Surya clearly answers to the same cosmic form as “the

high-wheeled chariot” of the Iranian Mithra.[449] An early form was the famous sun wheel of the

Babylonian Shamash.

Figure 15. The wheel of Shamash, held in place by a cord.

Figure 16. Triptolemus riding on a single wheel.

Figure 17. The wheel of Ixion.

Figure 18. Hebrew Yahweh on a single wheel.

Greek art depicts the great father Dionysus seated upon a one-wheeled chariot, much like that of the

old god Triptolemos. In the Astronomica of Hyginus one finds Triptolemos remembered as “the first

of all to use a single wheel.”[450] Argive tradition held that the father of Triptolemos was Trochilos,

“he of the wheel,” whom some identified as the inventor of the first chariot. The Greeks of Chios

knew the primeval god Gyrapsios, “he of the round wheel.”[451] Obviously, none of these wheels or

wheel gods can be separated from the famous wheel of Ixion, set loose in a celestial conflagration.

The Hebrew Yahweh similarly sits upon a single wheel.

While modern commentators offer competing interpretations of the cosmic wheel—the chariot of the

gods—few stop to notice the link with Saturn. Cook, for example, after a prolonged study of ancient

wheel symbolism, acknowledges Kronos (Saturn) as the old wheel or “disk” bearer, but is not

inclined to draw any conclusions from this.[452] The “inventor” of the wheel, or “chariot,” was the

now-distant planet. This is what the Chinese tell us when they report that the god-king Huang-ti, who

is identified with the planet Saturn, was the first to use the wheeled chariot. In more than one of the

illustrations presented here the cosmic wheel serves as the throne of the ruling god. L’Orange calls

this “the throne chariot,” noting many examples in the ancient Near East.[453] One of the divinities to

sit upon such a chariot (or wheel-throne) is the Hebrew Yahweh, whose seat is “the wheel of the

throne of his glory.”[454] (The god’s revolving throne is the circle of “glory”—that is, his own

“halo.”)

If later art showed the god on the wheeled seat, the original motif has the god in it, for the throne

revolves around the god. Here, for example, is a verse from the Egyptian Book of the Dead,

revealing a little-noticed aspect of the cosmic throne: “O my Seat, O my Throne, come ye to me, and

go ye round about me, O ye gods. I am a sah [luminous body], therefore let me rise up [shine] among

those who follow [go around] the great god.”[455] When the deceased king attains the celestial throne

he stands within the revolving circle of the gods, the “followers” of the central sun. The Edfu texts

call this the “throne-of-gods,” for the divine assembly itself forms the wheel of the throne.[456]

Figure 19. The Celtic god of the wheel.

Figure 20. Anglo-Saxon Seater, with wheel.

Denoted by the throne or wheel-throne is the plot of ta, “land,” which first emerged from the cosmic

sea. The creator brought forth the revolving circle of earth as his “primeval seat.” Reymond writes:

“The Earth was caused to emerge from Nun by virtue of the radiance of the Sun-God who was

believed to dry up the water around his primeval seat.”[457] This plot of created “earth” was the han

or “homeland,” which the texts call neset, the “throne.”[458]

The implications reach far beyond Egypt and bear directly on the wide-ranging myths of cosmic

chariots and primeval mills noted above. What one usually regards as two separate themes—the

“chariot of the sun” and the “world wheel”—converge in a single image: the wheel of Saturn, the

primeval sun. That the ancients denoted the “sun wheel” and the created “earth” by one and the same

sign was no coincidence.

The City Of Heaven

The Saturn myth tells us not only that the planet-god ruled the Holy Land as the first king but that he

founded the first city. Saturn’s “city” means “Saturn’s Earth.”

The great god lives

fixed in the middle of the sky . . .

dweller in the city.[459]

This is the pronouncement of the Egyptian Coffin Texts. The cosmic city is the Primeval Place: “I

have come to this city, the region of the ‘First Time’ to be . . . a dweller in ‘this land.’”[460] Thus the

Egyptians invoke a celestial Memphis, “the divine emerging primeval island”; a celestial Thebes,

“the island emerging in Nun which first came into being”; a celestial Hermonthes, “the high ground

which grew out of Nun,” or “the egg which originated in the beginning”;[461] a celestial Elephantine,

the “city in the midst of the waters,” or the “throne of Re”;[462] and a celestial Abydos, the ta-ur or

“Great (Primeval) Land.”[463]

The integrated symbolism—though at times complex—never departs from the underlying idea of an

enclosure around the central sun. The imagery concerns “the original state of the world,” rather than a

terrestrial city, states Clark.[464] Depicted is the city of the “dawn” or of the “sun’s coming forth.”

The tradition is universal. Mention Erech and historians naturally think of the ancient city in southern

Mesopotamia. But the Erech invoked in the ritual is no terrestrial habitation. It is:

Erech, the handiwork of the gods,

The great wall touching the sky,

The lofty dwelling place established by Anu.[465]

The creator An (Anu)—who is the planet Saturn—dwelt in the uru-ul-la, “the city of former times”—not a city on earth but the embryo of the Cosmos, according to Van Dijk.[466] Ruling from the “midst

of heaven,” An shines as “the hero of the sacred city on high.”[467] This is the “city founded by An . .

. Place where the great gods dine, filled with radiance and awe . . .”[468] The hymns call it “the great

city,” and “the place where the sun rises.”[469]

All Mesopotamian traditions describe the celestial city as the original garden of abundance—“the

dais of plenty . . . the pure place . . . Its heart like a distant shrine . . . Its feasts flow with fat and milk,

are rich with abundance.”[470]

Thus did the Sumerians recall the lost land of Dilmun as “the primeval city”:

Dilmun, the city thou hast founded . . .

Lo, thy city drinks water in abundance.

Lo, Dilmun drinks water in abundance.[471]

Egyptian and Mesopotamian descriptions of the cosmic city make clear that this habitation was the

same enclosure as the lost paradise, and the identity persists in Hebrew and Muslim thought, which

continually associates Adam’s paradise with a cosmic Jerusalem. The light of the Jerusalem above

was provided by God himself. “And the building of the wall of it was of jasper: and the city was pure

fold, like unto glass.”[472] One of the Psalms glorifies the celestial Jerusalem as “Sublime in

elevation in the uttermost north . . . the City of the King.”[473] The heavenly city lay at the cosmic

centre; it was the first thing created by God; and it was surrounded by the primeval sea. The image,

observes Faber, is “plainly borrowed from the garden of Eden.”

The Hebrews also preserved the tradition of a primordial city of Tyre, similarly identified with Eden.

[474] In Ezekiel we read:

“O Tyre, you have said,

‘I am perfect in beauty.’

Your borders are in the heart of the seas . . .

You were in Eden, the garden of God;

every precious stone was your covering.”[475]

This equation of the cosmic city and the original paradise finds numerous parallels in other traditions.

The Persian vara fashioned by Ahura Mazda is at once the first city and the lost paradise.[476] The

“all-containing city of Brahma” at the pole merges into the paradisal plain of Ila;[477] the Imperial

City of the Chinese Shang-ti coincides with the mythical paradise of Kwen-lun;[478] while the

Mexican lost city of Aztlan (“surrounded by waters”) and the Mayan lost city of Tula (the “enclosure”

in the sea) both appear as gardens of abundance.[479]

A coherent pattern unifies what are often assumed to be unrelated myths and symbols: the created

“earth,” the lost paradise, the wheel of the sun, the revolving throne, and the cosmic city. While the

mythical formulations vary, all point to the same band housing the central sun.

Surely it is of significance that, while these images are often dissociated in later myths, they

constantly overlap in the earliest versions. The Aztecs may have forgotten that the lost city was the

throne of the creator; and perhaps many Greek cults no longer remembered that the Island of the

Blessed was the turning wheel of the sun, but such connections are central to the world’s oldest

cosmologies.

The interrelationships are clearly evident in the image of the mother goddess, who unites in a single

personality the varied aspects of the celestial earth: paradise, wheel, throne, and city.

The Egyptian great mother—whether called Isis, Nut, Hathor, Mut, or Neith—is nebt en neter ta,

“the Lady of the Holy Land” or “the Lady of God’s Earth.” The “island of earth,” according to the

Pyramid Texts, lies “between the thighs of Nut.”[480] If one permits the Egyptian concept to

illuminate later symbolism of the “mother earth” one sees that the supposed distinction between earth

goddesses and sky goddesses lacks foundation. “God’s Earth” means Saturn’s Earth, and this mother

land, circumscribed by the womb of the goddess, is the enclosure of the central sun.

Nor can one fail to notice that the hieroglyph for the goddess Nut —“the holy abode”—is the form of a wheel and an obvious prototype of the “world wheels” so common to Eastern symbolism. Isis, in

the classical age, was also symbolized by a wheel.[481]

Mesopotamian cults represented the goddess Ishtar, “the womb,” by a wheel. The Hindu goddess Rta

is the “wheel of law” controlling the cosmic cycle, while the goddess Ila personifies the chakra or

world wheel. The name of the Celtic goddess Arianrhod means “silver wheel.” One is reminded also

of the iynx wheel of Aphrodite and the wheels of Tyche, Nemesis, and Fortuna, all of which appear to

reflect a common idea. As the stable, ever-turning circle of the Cosmos, the goddess eventually

became the abstract “wheel of Mother Nature.”[482]

And when one realizes that the wheel served as the great father’s revolving throne it can come as no

surprise to discover that, in the archaic terminology, “throne” and “goddess” are synonymous. “The

seated great mother,” states Neumann, “is the original form of the‘enthroned goddess,’ and also of the

throne itself. As mother and earth woman the Great Mother is the ‘throne’ pure and simple . . . The

king comes to power by ‘mounting the throne’ and so takes his place on the lap of the Great Goddess,

the earth—he becomes her son.”[483]

Figure 21. The goddess Nemesis, with wheel of fate.

In the Hindu kingship rites reviewed by Hocart, “the king is made to sit on a throne which represents

the womb.”[484] But the identity of the throne and womb is as old as human language: the Egyptian

hieroglyph for Isis, the womb of heaven, is a simple throne .

But the same mother goddess encloses the cosmic city. The determinative of “city” in the Egyptian

hieroglyphs is simply the sign of the “holy abode” , the goddess Nut. The Pyramid Texts invoke the

goddess, “in this your name of ‘settlements,’ . . . in this your name of ‘City.’”[485] while the Book of

the Dead extols the great mother as “Lady of terrors, lofty of walls.”[486]

The Egyptian city-goddess finds a close parallel in the Babylonian goddess Ura-azaga, whose name

means “brilliant town.”[487] Tyro, the mother goddess of the Tyrians, gave the Greeks their word

tyrsis, “walled city.”[488] To enter the celestial city is to find shelter in the primeval womb. Thus the

refuge of Delphi is “the womb” and Jerusalem “the city of the heavenly womb.”[489]

In the New Testament (Book of Revelation) one finds a fascinating equation of primeval goddess and

primeval city. In his vision, John beholds “the great whore that sitteth upon many waters: With whomthe kings of the earth have committed fornication . . . and upon her forehead was a name written,

‘MYSTERY, BABYLON THE GREAT, THE MOTHER OF HARLOTS AND ABOMINATIONS OF

THE EARTH.” Who was this “mother of harlots”? The angel explains: “And the woman which thou

sawest is that great city, which reigneth over the kings of the earth.”[490] The language points to the

ancient rites of kingship, in which every local ruler took as his consort the city (womb) on the cosmic

waters.

In ranging over the myths and symbols of the created earth, paradise, wheel, throne, and city, one thus

remains in the shadow of a single mother goddess, who contains within her womb the first organized

domain in heaven, the island of Saturn’s Cosmos .

The Enclosure As Prototype

In dealing with the myths and symbols of the Holy Land one must reckon with the distinction—not

always spelled out in ancient literature—between the celestial prototype and the terrestrial copy.

Every sacred kingdom or city derives its character from the primeval dwelling, so that whatever was

said of the enclosure above was also said of the imitative form constructed by men.

“From the concordant testimony of all the traditions,” writes Guenon, “a conclusion emerges very

clearly: the affirmation that there exists a ‘Holy Land’ par excellence, prototype of all other ‘Holy

Lands,’ the spiritual centre to which all other centres are subordinated.”[491]

Through identification, the sacred history of the race or nation merges with the history of the gods, for

each organized community viewed itself as a duplication of the celestial “race.” Each line of

historical kings leads back to a first king who is not a man, but Saturn, the supreme power of heaven;

in the same way, the race as a whole traces its ancestry to a generation of gods or semi-divine beings

who inhabited the “earth” raised in the creation. By this universal tendency, Saturn’s paradise

becomes the ancestral land, the place where history began. Does not every nation claim that its

ancestors descended from a race of gods, who occupied a happy garden at the centre and summit?

It was with the utmost seriousness that the ancients laid out their first political settlements, taking the

cosmic habitation as the prescribed plan. The purpose was to establish Saturn’s kingdom on earth,

repeating the creator’s defeat of Chaos and founding a central authority whose power extended to a

protective “border” separating the kingdom of light from the powers of darkness and disorganization

(the “barbarians”).

Accordingly, the first sacred cities were organized as circular enclosures around the ruling lord.

Ritual requirements superseded practical considerations, and even when geography and growth

prevented or distorted the purely circular form, the sacred city was still conceived as a revolving

enclosure. Symbolically, every Egyptian city lay within the shield or protective border of Nut (the

“Great Protectoress”). The Babylonian map shows the land as a circle around a centre. “Here,”

concludes Eliade, “the earthly abode is the counterpart (mehret) of the heavenly abode.”[492]

Hebrew thought repeatedly insists that the terrestrial Jerusalem was but a likeness of the city first

constructed by God. “A celestial Jerusalem was created by God before the city was built by the hand

of man . . . The heavenly Jerusalem kindled the inspiration of all the Hebrew prophets,” observes

Eliade.[493] The distinction between the local and the primordial city receives emphatic statement in

the Syriac Apocalypse of Baruch, when God asks, “Dost thou think that this is that city of which I

said: ‘On the palms of my hands have I graven thee’? This building now built in your midst is not that

which is revealed with me, that which was prepared beforehand here from the time when I took

counsel to make Paradise . . .”[494] (Again, note the equation of the city—Jerusalem and paradise.)

Equally clear is the primacy of the archetypal city in Hinduism, according to Eliade. “All the Indian

royal cities, even the modern ones, are built after the mythical model of the celestial city, where, in

the age of gold (in illo tempore), the Universal Sovereign dwelt . . . Thus, for example, the palace

fortress of Sigiriya, in Ceylon, is built after the model of the celestial city Alakamanda and is ‘hard of

ascent for human beings’”[495]

Symbolically, each Hindu settlement stood within the mandala or “circle,” delineating a consecrated

space magically protected from the invading forces of disintegration.[496] The sanctified area,

observes Tucci, “by the line of defense which circumscribes it, represents protection from the

mysterious forces that menace the sacred purity of the spot . . .” This protective circle is “above all, a

map of the cosmos.”[497]

As documented by L’Orange, the circle around a centre was the ideal form of sacred cities in the Near

East, as typified by the residential cities of Darabjerd and Firuzabad, whose circular form served as a

precedent for the “Round City” of Baghdad. The ideal pattern derived from the ancient conception of

the Cosmos, states L’Orange.[498]

The same symbolism attaches to the Roman mundusa trench dug around the spot on which a new city

was to be built. The enclosure served as a protective bond, ordaining the city as a renewal of the

primeval homeland.[499] In the old documents the Roman cities were the urbes, from orbis,

“round.”[500]

The consistent pattern of the sacred territory shows the influence of a universal prototype. Yet few

researchers take the prototype seriously. When the creation myths speak of a primordial Heliopolis,

Erech, or Jerusalem, the analysts think only of the terrestrial city. One can, with far greater assurance,

insist that the local habitation never produces, on its own, a cosmic myth of any kind.

In Egypt, it is the primeval sun who rules the original Heliopolis, Memphis, Thebes, Herakleopolis,

just as it is the primeval sun who governs as the first king of Egypt as a whole. The city and kingdom repeat, on different scales, the same history and this fact alone is sufficient to show that the “history”

is not local but universal. If the myths say that Egypt was “gathered together” from the primeval

matter, forming an island around the sun, they say the same of the sacred city, whatever its name.[501]

That the ancients often forgot the distinction between their own city or kingdom and the celestial

prototype was a natural result of the inseparable bond between the two. The local habitation inherited

the mythical character of the celestial, so that the divergent actual histories of ancient nations lead

back to one universal history.

It is in this sense that one must understand the legends of the first kings and primeval generations.

Many Egyptian texts, for example, refer to a remote time in which the land was ruled by the

“followers of Horus.” An inscription of a King Ranofer (just prior to the Middle Kingdom) recalls

“the time of your forefathers, the kings, Followers of Horus.” A text of Thutmose I speaks of great

fame the like of which was not “seen in the annals of the ancestors since the Followers of Horus.”

The Turin Papyrus places this primeval generation prior to the first historical king, Menes.[502]

Did these mythical “ancestors” actually rule terrestrial Egypt? In truth the “Followers of Horus”

means, not a generation of mortals, but the assembly of the gods. The “ancestors” were the light spirits of the celestial city, encircling and protecting the central sun. Just as the myths translate the

Universal Monarch into the first king of Egypt, so also do they express the god-king’s companions as

a primeval race from which all Egyptian nobility might claim descent. Every Holy Land on our earth

was assimilated to the same celestial kingdom and every race to the same generation of gods.

The World Navel

Through identification with Saturn’s dwelling, each terrestrial kingdom or city of antiquity

distinguished itself as the Middle Place, the centre from which history took its start. Symbolically

each local Holy Land became the omphalos or “navel of the world.”

Thus, the mythic navel constitutes a global motif of archaic symbolism. As documented in the separate

studies of Roscher and Muller,[503] the ancient cities of Babylon and Nineveh (as well as Baghdad),

Jerusalem, Hebron Bethel, Shechem, and the entire land of Palestine; numerous Greek cities

(including Athens); the Muslim city of Mecca; and countless other cities of Asia and Europe were

styled “the navel” or “the centre of the earth.”

Just as the Egyptians conceived their land as the “middle-earth” (Aguipte), the Chinese proclaimed

their empire to be the “Kingdom of the Middle.”[504] Early Japanese sources call Japan the centre of

the earth—or the “middle kingdom of the reed plain,” while the Mongolians regard their home as “the

Middle Place.”[505] Peoples of northern Siberia know the Yenisei as “the centre of the world,”[506]

Ireland was once the kingdom of the Mide or “Middle.”[507]

In faraway Easter Island the natives speak of their land as the “navel.”[508] And in the Americas, the

Zuni call (or once called) their town “the Middle Place”; the Inca city of Cuzco signified “the navel

of the earth”;[509] so also did the Chickasaw of Mississippi regard their territory as “the centre of

the earth.”[510]

The reader may respond: isn’t it perfectly natural that a people, seeing other lands and nations

distributed around them, would come to regard their own as the “centre”? This is, of course, a

common explanation of the universal habit. On closer examination, however, it becomes clear that the

concept of the world navel reflects something more than narrow vision or tribal arrogance.

The acknowledged religious centre of the Greeks was Delphi, on the steep slopes of Mount

Parnassus. Here was located the omphalos (“navel”), revered as the Seat of Apollo and “the centre of

the earth.” But among the Greeks, Delphi was not alone in claiming distinction as the omphalos.

Similar claims were made for world navels in the Peloponnesus, at Elis, at Thessaly, and at Crete.

Both the Aetolians and Epirotes were called omphalians or “people of the navel.”[511]

Many competing seats of Apollo appear as the omphalos, according to Roscher.[512] Rather than

suggest narrow-mindedness, such repeated claims confirm a consistent memory: from high antiquity

the idea must have been passed down that Apollo’s throne occupied the “centre.” All local shrines

certainly shared this tradition. But one must not mistake the imitation for the original. Just as one

might say of Apollo’s statue, “This is the god Apollo,” without intending a literal identification, so

could the cult worshippers say of the local shrine, “This is the throne of Apollo at the earth navel.”

That the statement comes from more than one locality only reinforces the general tradition. The truth

was observed by W. T. Warren long ago when he declared Delphi to be “a memorial shrine, an

attempted copy of the great original.”[513]

Clearly, the “great original”—the god’s primeval home—was not of our earth. Apollo, the polar sun,

was not the only god to occupy this centre. In Mexico, a Nahuatl hymn extols the god Ometeotl as:

Mother of the Gods, Father of the Gods,

the old God

distended

in the navel of the earth,

engaged in the enclosure of turquoise

He who dwells in waters the colour of the bluebird.[514]

A Babylonian hymn located the god Ea at the “centre of the earth”:

The path of Ea was in Eridu, teeming with fertility.

His seat (there) is the centre of the earth;

his couch is the bed of the primeval

mother.[515]

Similarly, the Egyptian Osiris “sits in judgement on the Primeval Mound, which is in the middle of the

world,” states Clark.[516] In the ancient account of Sanchuniathon, the great god El (Kronos/Saturn)

acquires supremacy “in a certain place in the center of the earth.”[517]

The earth navel, in the original tradition, is the inaccessible dwelling at the cosmic summit which

is why the Hindus could say of the fire god Agni,[518] “He is the head and summit of the sky, the

centre [Nabhi, navel] of the earth.” Hebrew and Muslim thought constantly identifies the throne of

Yahweh and Allah with the “navel of the earth,” but this navel is above, for the Muslim text states of

the Ka’ba, or earth navel: “Know that the centre of the earth, according to a tradition on the authority

of the Prophet, is the Ka’ba: it has the significance of the navel of the earth, because of its rising

above the level of the earth.”[519]

Another source relates, “Tradition says: the polestar proves the Ka’ba is the highest situated

territory; for it lies over against the centre of heaven.”[520] Both Jerusalem and Mecca, as earth

navels, lie at the cosmic summit. “The centre of the earth and the pole of heaven, both are intimately

connected with the throne,” observes Wensinck.[521]

Similarly, Gnostic traditions surveyed by Jung consider the polar region both “the seat of the highest

gods” and “the navel of the world.”[522] That the Greek omphalos received the appellation “axis”

indicates an obvious connection with the pole.[523]

In all of these traditions, of course, one has to contend with the confusion between the celestial earth

and what we call “earth” today. It can hardly be doubted that ancient races eventually came to use the

phrase “world navel” in connection with the terrestrial landscape. The original concept of the navel,

however, is not complicated by ambiguous meanings of the “earth.” In the original tradition, the

created earth is the navel, pure and simple; Saturn’s Cosmos appeared as a central enclosure or

“navel” of dry ground rising from the primordial waters. So it is not surprising to find that the symbol

of the navel was the enclosed sun , the sign of the world wheel. “The concentric circles or the

dot-in-circle denoted, in the Mediterranean area, the omphalos, the navel of the earth,” states

Butterworth.[524] (Thus, in organizing their sacred cities in the form of a wheel the ancients

expressed the cities’ character as “navel.”)

The enclosed sun , according to Neumann, served as “the life symbol of the womb-navel centre.”[525] It would be difficult to improve upon this definition. To reside within the life containing navel is to dwell in the womb of the mother goddess, for the omphalos, as discerned by

Uno Holmberg, is “the representative of the Great Mother” not only in classical symbolism but in

Hindu and Altaic ritual also.[526]

Hence Delphi, the Greek omphalos, signifies “the womb.”[527] The spouse of Hercules is Omphale,

the female personification of the omphalos.[528] In the same way, Hindu ritual constantly identifies

the mystic yoni or “womb” with the navel: Agni is “born from the yoni or navel of the earth,”[529]

while Brahma is the “navel-born.”[530]

Such symbolism connects the famous navel with the primeval enclosure. Saturn’s band, marking out

the stable, revolving island which appeared in the cosmic waters, came to be remembered as the

cosmic centre—where mythical history began.

The Ocean

Many ancient traditions describe a circular ocean or river girdling the “earth.”

The gods, according to the Norse creation legend, “made the vast ocean, in the midst of which they

fixed the earth, the ocean encircling it as a ring.”[531] By the Greek Okeanos, “the whole earth is

bound.”[532] The Babylonians said of the nether river, “all earth it encloses.”[533] Hebrew and

Arabic cosmologies, according to Wensinck, hold that “the whole of the earth is round and the ocean

surrounds it like a collar.”[534]

In spite of the widespread belief, certain classical writers grew skeptical. Of the famous ocean stream the historian Herodotus announced: “For my part, I cannot but laugh when I see numbers of

persons drawing maps of the world without reason to guide them; making, as they do, the Ocean stream to run all round the earth.”[535]

Or again: “The boundaries of Europe are quite unknown, and there is not a man who can say whether

any sea girds it round either on the north or on the east.”[536] Such was the inevitable conclusion of

historians and philosophers, once the “world” or “earth” lost its original cosmic meaning and passed

into a figure of geography. Even today conventional treatments of the mythical ocean perpetuate the

misunderstanding.

The cynics overlooked a most significant point: originally, the ocean encircled the creator as a

girdle: Okeanos was no terrestrial river, but the “belt” around the cosmic deity.[537] The “land”

which the ocean enclosed was the dwelling of the gods. Hesiod, for example, in his description of the

shield of Hercules (an acknowledged figure of the Cosmos) identifies the ocean as the rim of the

shield, enclosing a celestial paradise.

The shield was a wonder to see, “for its whole orb was a-shimmer with enamel and white ivory and

electrum, and it glowed with shining gold.” Within the shield’s protective enclosure dwelt the great

god and the lesser divinities: “There also was the abode of the gods, pure Olympus, and their

assembly, and infinite riches were spread around in the gathering of the deathless gods.” The

inhabitants of this circular land above celebrated a continual festival, for here grew grapes and corn

in abundance. “And around the rim,” writes Hesiod, “Ocean was flowing, with a full stream as it

seemed, and enclosed all the cunning work of the shield.”[538]

As in the case of the world navel, the imagery makes sense only when one understands the created

“earth” as the dwelling of the great god himself.

Egyptian sources remove all possible doubt as to the celestial character of the encircling stream. The

Coffin Texts say of the Father of the Gods: “the river around him is ablaze with light.”[539] The same

circular river is called a lake of fire. Re appears as ami-mer-nesert, “he who is in his fiery lake”;

while the throne of Horus is the “Lake of Double Fire.”[540]

Actually, the Egyptian ocean or lake is simply the Tuat, the dwelling of Osiris or Re:[541] “This is

the lake which is in the Tuat . . . This lake is filled with barley [i.e., grain, abundance]. The water of

the lake is fire.”[542]

Containing the fiery waters of the Abyss, the celestial river or lake encircled the “world.” The

Pyramid Texts invoke:

The Great Circle, in your name of

“Great Surround,”

an enveloping ring, in the

“Ring that encircles the

Outermost Lands”,

A Great Circle in the Great Round of

the

Surrounding Ocean.[543]

In the Egyptian symbolism this watery circle is the band of the enclosed sun , the band which

circumscribed the outermost limit of the cosmic dwelling. The “ocean” in the above text is the Shenur, or “the great Shen.” In the Egyptian language the shen bond or cord ( , ) signifies at once the

band of the Aten and “ocean” or “river.” One can properly term this circle of water “the river of the

cosmic bond” or “the ocean of the cord.”

Pointing to the same interrelationships is the Egyptian word nut. Nut, the goddess, is the female

personification of the Cosmos or shen bond; but nut also denotes “stream,” “river,” “sea.” The

encircling river, as the border of the “Holy abode” (nut), thus gives rise to the phrase “the ocean, the

border of Nut.”[544] That nut further means “cord” and “city” only confirms the integrated

symbolism.

In none of this symbolism is there any suggestion of a terrestrial ocean. As detailed by Reymond, the

primeval waters form an enclosure around the resting place of the great god “perhaps resembling the

channel which was made around sacred places later on.”[545] Encircled by the celestial river, the

province of beginning becomes the “island in the stream,”[546] or the “pool.” (See, for example, the

“pool of Hermopolis”; the celestial Abydos was the “pool of Maati.”)[547]

The mythical “waters” are inseparable from the primeval matter or company of gods which exploded

from the creator, subsequently to be gathered into the circle of glory (khut). The radiant gods—or

“Primeval Ones”—revolved around the border of the cosmic ocean or lake, for the Egyptians,

according to Reymond, “imagined that, after the phases of the primary creation were completed, these

Primeval Ones lived in the vicinity of the pool . . . Their resting place, however, is portrayed as of

the most primitive appearance: the bare edges of the pool.”[548] The gods occupy the border and

revolve around it, as confirmed by the Book of the Dead: “‘Hail,’ say these gods who dwell in their

companies and who go round about the Turquoise Pool.”[549]

Nor in Egypt alone does the cosmic ocean form the band of the enclosed sun . Here is a Sumerian

description of the Engur or “river” around the motionless lord Enki:

Thou River, creatress of all things,

When the great gods dug thee, on thy bank they placed mercy.

Within thee Ea, King of the Apsu, built his abode.

They gave thee the Flood, the unequalled.

Fire, rage, splendour, and terror . . .

O great River, far-famed River . . .[550]

These are the waters of the cosmic sea Apsu—“the waters which are forever collected together in

the deep,”[551] corresponding to the Egyptian dwelling gathered together by the creator. The oldest

image of this encircling river or ocean is the ancient Sumerian sign for Kis (the all, the complete

land, the Cosmos): . The band in this sign, according to Jeremias, represents the encircling ocean,

the same river that is depicted encircling the “earth” (Cosmos) in the Babylonian world map.[552]

Like the Egyptian ocean the revolving stream forms the border of the celestial land.

As the womb of primeval birth, the Sumerian Engur, “River,” provides a close parallel to the

Egyptian goddess Nut. Indeed, like Nut, the Sumero-Babylonian river goddess was conceived as the

unifying cord. The waters of Engur (Apsu) compose the tarkullu, “rope,” or the markasu, “band,”

bond,” holding together the created Cosmos.[553] Like the Egyptians, the Sumero-Babylonians

recalled the enclosure of the cosmic ocean as that which gave birth to the primeval sun. The god who

“illuminates the interior of the Apsu” is Ninurta, the planet Saturn.[554]

VI.

The Enclosed Sun-Cross

The Four Rivers Of Paradise

“And a river went out of Eden to water the garden; and from thence it was parted, and became into

four heads.”[555] So reads the Book of Genesis. The four rivers of Adam’s paradise, according to

many Hebrew and early Christian accounts, flowed in opposite directions, spreading to the four

corners of the world.[556]

The tradition is apparently universal. The Navajo Indian narration of the “Age of Beginnings” speaks

of an ancestral land from which the inhabitants were driven by a great catastrophe. Among the

occupants of this remote home, some say, were “First Man” and “First Woman.” Most interesting is

the means by which the land was watered: “In its centre was a spring from which four streams

flowed, one to each of the cardinal points . . .”[557]

The Chinese paradise of Kwen-lun, adorned with pearls, jade, and precious stones, lay at the centre

and zenith of the world.[558] In this happy abode stood a central fountain from which flowed “in

opposite directions the four great rivers of the world.”[559]

Four rivers appear also in the Hindu Rig Veda: “the noblest, the most wonderful work of this

magnificent one [Indra], is that of having filled the bed of the four rivers with water as sweet as

honey.”[560] The Vishnu Purana identifies the four streams with the paradise of Brahma at the world

summit. They, too, flow in four directions.[561]

Iranian myth recalls four streams issuing from the central fount Ardvi Sura and radiating in the four

directions. Similarly, the Kalmucks of Siberia describe a primordial sea of life and fertility, with four

rivers flowing “toward the four different points of the compass.”[562]

The tradition is repeated by many other nations. The Mandaeans of Iraq enumerate four great rivers

flowing from the north.[563] Just as the Babylonians recalled “the land of the four rivers,”[564] the

Egyptians knew “Four Niles,” flowing to the four quarters.[565] The home of the Greek goddess

Calypso, in the “navel of the sea,” possessed a central fountain sending forth “four streams, flowing

each in opposite directions.”[566]

In the Scandinavian Edda, the world’s waters originate in the four streams flowing from the spring

Hvergelmir in the land of the gods,[567] while Slavic tradition recalls four streams issuing from under the magic stone Alaturi in the island paradise of Bonyan.[568] Brinton finds the four mystic

rivers among the Sioux, Aztecs, and Maya, just as Fornander discovers them in Polynesian myth.[569]

The lost land of the four rivers presents a particularly enigmatic theme for conventional mythology

because few, if any, of the nations possessing the memory can point to any convincing geographical

source of the imagery. When the Babylonians invoke Ishtar as “Lady, Queen of the land of the Four

Rivers of Erech,”[570] or when an Egyptian text at Dendera celebrates the Four Niles at Elephantine,

one might expect the familiar landscape to explain the usage. But wherever the mythical four rivers

appear, they possess the character of an “ideal” land, in contrast to actual geography.

The reason for this disparity between the mythical and terrestrial landscapes is that the four rivers

flowed, not on our earth, but through the four quarters of the polar “homeland.” To what aspect of

Saturn’s kingdom might the mythical rivers refer?

For every dominant mythical theme there are corresponding signs (though this truth is still to be

acknowledged by most authorities). The signs of the four rivers are the sun-cross and the

enclosed sun-cross , the latter sign illuminating the former by showing that the four streams belong

to the primeval enclosure. Issuing from the polar centre (i.e., the central sun), the four rivers flow to

the four corners of Saturn’s Earth.

The sign of the enclosed sun-cross , observes Cirlot, “expresses the original Oneness (symbolized

by the centre),” and “the four radii . . . are the same as the four rivers which well up from the fons

vitae . . .”[571]

But if one myth identifies the arms of the sun-cross as four paradisal rivers, there are other

interpretations of the cross as well, for this primal image produced a wide-ranging and coherent

symbolism, as I shall now attempt to show.

The Crossroads

From Saturn, the central sun, flowed four primary paths of light. In the myths these appear as

four rivers, four winds, four streams of arrows, or four children, assistants, or light-spirits bearing

the Saturnian seed (the life elements) through the four quarters of the celestial kingdom.

The sun-cross and enclosed sun-cross , depicting the four life-bearing streams, thus serve

as universal signs of the Holy Land.

The modern world is accustomed to think of “the four quarters” in terrestrial terms. Today we

conceive north, east, west, and south only in relationship to our own position or to a fixed

geographical reference point. Chicago is “west” of New York and “east” of Omaha, and to the

modern mind the “four corners of the world” only serves as a vague metaphor for “the entire globe.”

To the ancients, however, “the Four Corners of the World” possessed explicit meaning; originally, the

phrase referred not to geography but to cosmography, the “map” of the celestial kingdom, laid out in

the polar heaven. One of the few scholars to recognize this quality of the mythical “four corners” was

O’Neill: “It results from any full study of the myths, symbolism, and nomenclature of the Four

Quarters that these directions were viewed in the strict orthodoxy of heavens-mythology, not as the

NSEW of every spot whatever, but four heavens-divisions spread out around the pole.”[572]

The sun-cross , as the symbol of the four quarters, belongs to the central sun. In sacred

cosmography the central position of the sun-god becomes the “fifth” direction. To understand such

language, it is convenient to think of the mythical “directions” (or arms of the cross) as motions or

flows of energy. From the great god the elements of life flow in four directions. The god himself, who

embodies all the elements, is “firm,” “steadfast,” or “resting”; his fifth motion is that of rotation

while standing in one place.

The directions can also be conceived as regions: the central (fifth) region and the four quarters

spaced around it.

This is why the Pythagoreans regarded the number five as a representative of the fixed world axis.

[573] The Pythagorean idea clearly corresponds with the older Hindu symbolism of the directions. In

addition to the standard four directions, Hindu doctrine knows a fifth, called the “fixed direction,” the

polar centre.[574]

In China, too, the pole is the immovable fifth direction, the “central palace” around which the

cardinal points are spaced.[575] And in Mexico, Nahuatl symbolism asserts that “five is the number

of the centre.”[576]

In the “ideal” kingdom of heaven the Universal Monarch stands at the centre, and all the elements of

life—fire, water, air, and seed—flow from the god-king in four brilliant streams. Often interpreted as

four sons of the creator, the streams mark out the four quarters of the cosmic isle, or “earth.”

Let us consider first the Egyptian symbolism of the directional streams. According to the Egyptian

creation texts, the great god, standing alone, brought forth as his own “speech” the primeval matter—or sea of “words”—which congealed into an enclosure. The Egyptians associate this pouring out of

the seed or life elements with four luminous streams flowing from the central sun. The four

emanations are the four “sons” of Atum or the Four Sons of Horus, each identified with a quarter of

the heavenly kingdom.[577] Importantly, the Egyptians term these paths of light the “Four Khu”: they

are the “words of power”—streams of creative “speech” coursing through the four divisions of

organized space.

The Pyramid Texts call these “the four blustering winds which are about you.”[578] The Four Sons of

Horus “send the four winds.” In one source the four winds issue from the mouth of Amen.[579] In the

Book of the Dead they are “the four blazing flames which are made for [or as] the Khu [words of

power],”[580] while the Cof in Texts invoke them as the “four gods who are powerful and strong,

who bring the water.”[581]

The Egyptians also interpreted the four paths of light as “arrows” launched by the creator toward the

four quarters. (In hieroglyphs, the arrow means “shaft of light.”) It was an ancient practice of the

Egyptian king, on assuming the throne, to release an arrow, in each of the four directions,[582] thus

reenacting the creation, or organization of the celestial kingdom. The arrow is sat, which means “to

shoot,” but also “to pour out”; for the four arrows launched by the king signified the waters of life

originally “poured out” by the creator, whom the king personified. Sat also means “to sow” or “to

scatter seed abroad”; which is to say, the four streams carried to the four corners the creative seed of

abundance.[583] By launching the four arrows the local king proclaimed himself the Universal

Monarch and sanctified his kingdom as a duplication of the primeval abode.

In Egypt the cross—as the symbol of the four directional streams—possesses two important

meanings. The form , un, signifies “coming to life,” for the directional streams shone forth with

the daily birth of the central sun (i.e., with the setting of the solar orb). In the form (or ), ami,

the cross means “to be in” or “to be enclosed by”—in reference to the unified space enclosed within

the womb of the mother goddess .

When certain Egyptologists first encountered the symbol of the goddess Nut , they saw in it “a

pictorial symbol of primitive Eden divided by the four-fold river.”[584] That conclusion would gain

little credence among modern Egyptologists, yet it is much closer to the truth than the bland

explanations currently in fashion. The four streams of life, emanating from the creator, coursed

through the womb of Nut, the Holy Land. Thus the deceased implores the goddess, “Give me the

water and the wind which are in thee.”[585]

Another symbol of the “holy abode” is the sign [586] showing a cross of arrows superimposed

upon a shield. The glyph is precisely equivalent to the symbol of Nut , for Nut, the Great

Protectoress, was the cosmic shield, and the four streams of life, enclosed within the womb of Nut,

were the same as the shafts or arrows of light launched toward the four corners.

The land of the four rivers was that which the creator gathered together from the sea of words, his

own emanation. The hieroglyphic symbol for “to collect, gather together” and for “the unified land”

is , depicting the primeval enclosure (shen) divided into quarters by a cross of two flails. That

the flail sign , in the Egyptian language, is read Khu, equates the flail-cross with the four streams

of life (khu, “words of power”) radiating from the central sun.

There is, in other words, a level of Egyptian symbolism that the specialists have yet to penetrate.

Standard treatments of the Egyptian Holy Land say little or nothing of the directional streams, though

these powers are vital to the symbolism as a whole. And one can be certain that the paths of light and

life have nothing to do with an ill-defined “four quarters” of our earth, where they are conventionally

located. The four winds, or four rivers, or four pathways, or four shafts of light (arrows) belonged to

the lost land in heaven, and only through symbolic assimilation to this cosmic dwelling did the

terrestrial habitation share in the imagery.

A comparison of Egyptian cross symbolism with that of other lands reveals numerous parallels. The

oldest Mesopotamian image of divinity was the sun-cross , symbol of the creator An, the planet

Saturn. An, like his counterparts around the world, “brought forth and begat the fourfold wind” within

the womb of Tiamat, the cosmic sea.[587]

The cult worshippers of Ninurta (Saturn) also represented their god by the cross. Hence, the

cuneiform ideograms for the fourfold saru, “wind,” and for mehu, “storm wind”—both of which

belong to Saturn—take the form of a cross (figs. 22 and 23). The Babylonian Saturn inaugurates the

day, “coming forth in splendour,” and this coming forth of Saturn means the coming forth of the four

winds (as in Egypt), for the Akkadian umum denotes both “day” and “wind,” just as the Sumerian

signs UD and UG, both used for “day,” occur also in the sense of “wind.”[588] (The ancient Hebrew

expression “until the day blows” conveys the same identity.)

Figure 22. Babylonian saru, “wind.”

Figure 23. Ideogram for mehu, or “storm wind.”

Saturn’s four winds mark out the quarters or directions of the Cosmos, Saturn’s kingdom.

Cosmological texts speak of the “furious wind . . . commanding the directions”:[589] the Sumerian im

and Akkadian saru, “wind,” also signify “region (or quarter) of heaven.”[590]

As in Egypt, the Mesopotamian four winds coincide with the four rivers of life. Instead of the simple

sign , some images show four streams of water radiating from the central sun (fig. 24).[591] The

best-known Mesopotamian figure of these streams is the famous “sun wheel” of Shamash (a god also

identified as Saturn). Portrayed are four rays of light and four rivers flowing from the central god to

the border of the wheel (fig. 15).

Hrozny tentatively suggests that Shamash’s cross was a sign for “settlement.”[592] With this

suggestion one is compelled to agree, for the first settlements, organized for a ritual purpose, imitated

the heavenly abode. Each sacred territory became “the land of the four rivers” and each ruler “the

king of the four quarters.”

Geographical limitations did not prevent the Assyro-Babylonian priests from assimilating the map of

their land to the quartered circle of the primeval kingdom. Thus a text reproduced by Virolleaud

locates the land of Akkad, Elam, Subartu, and Amurru within the fourfold enclosure of the sun .

[593] “Every land,” states Jeremias, “has its ‘paradise,’ which corresponds with the cosmic

paradise.”[594]

The land of the sun-cross lay within the primeval circle, and this fact will explain why the

Babylonian sign of the four kibrati or “world quarters” (i.e., ) also denoted “the interior” or “the

enclosed space.”[595] The terminology offers a fascinating parallel to the Egyptian ami ( , ),

“to be in,” “to be enclosed by.” To dwell in the land of the four rivers is to occupy the Saturnian

enclosure.[596]

The same overlapping interpretations of the four streams occur in Hindu symbolism. Here the cross

and the circle, according to one observer, represent “the traditional abode of their primeval ancestors

. . . And let us ask what better picture or more significant characters in the complicated alphabet of

symbolism could have been selected for the purpose than a circle and a cross—the one to denote a

region of absolute purity and perpetual felicity, the other those four perennial streams that divided and

watered the several quarters of it.”[597]

The Hindu Holy Land lies within the world wheel, turned by the stationary sun at the centre. The

spokes of the wheel, delimiting the four quarters, “have their foundation in the single centre which is

Surya [the sun],” notes Agrawala.[598]

In the ritual of the Satapatha Brahmana the spokes of the wheel become “arrows” launched in

the four directions and carrying the life elements to the four corners. The arrows sent in one direction

“are fire,” those in another “are the waters,” those in another “are wind,” and those in another “are

the herbs.”[599] The Paippalada or Kashmirian Artharva Veda terms the latter flow of arrows

“food.” The idea seems to be that of abundance or “plenty” radiating from the heart of the Cosmos

(and thus answering to the four Egyptian arrows [sat] transmitting the seed of abundance to the

outermost limits of the kingdom). The Hindus symbolized these shafts of light by setting afire the

spokes of the sacred wheel.[600]