Tweed might just be the original political crook,and Washington has nothing on Tammany,even today as the state of New York,along with a few other states have far too much influence over how the federal government operates and for whom...

The History of Tammany Hall

By Gustavus Myers

CHAPTER XXIV

Tweed in His Glory

1870-1871

Tweed in His Glory

1870-1871

URGED by various motives, a number of Tammany leaders combined against Tweed. Some sought more plunders others felt that their political aspirations had not been sufficiently recognized, and a number were incensed against Sweeny. They were led by Henry W. Genet, John Fox, John Morrissey, James O’Brien, “Mike” Norton and others, and called themselves the “Young Democracy.” Tweed had used these men in building his power; now, combined, they believed they could retire him. The dangerous classes joined them. Heretofore, these had stood by Tweed under a reciprocal agreement valuable to both sides. But the “Boss” had recently yielded to the public indignation over the leniency shown to an influential murderer, and had given orders to the Judges to deal more severely with flagrant criminal cases. This act constituted a virtual breaking of the compact, and the lawbreakers with one accord turned against him. There were at this time in the city, it was charged, about 30,000 professional thieves, 2,000 gambling establishments and 3,000 saloons.[1]

The plan of the Young Democracy leaders was to induce the Legislature to pass a measure known as the Huckleberry charter, the object of which was to abolish the State commissions governing the city and to obtain a relegation of their powers to the Board of Aldermen. The disclosure was made, many years later, that Richard Croker and seven other members of the Board of Aldermen had signed an agreement before a notary public, on March 20, 1870, pledging themselves to take no official action on any proposition affecting the city government without first obtaining the consent of Senator Genet and four other Young Democracy leaders.[2] These latter boasted that they would “put the charter through” if it took $200,000 to do it. To save himself, Tweed opened a half-way understanding with the Young Democracy chiefs, by which he was to join them and abandon Sweeny. Tweed even offered — though vainly — one of the most formidable young leaders $200,000 outright if he would swerve the Young Democracy to his interest.

The Young Democracy succeeded in winning over a majority of the general committee, and influenced that majority to call a meeting to be held in the Wigwam, on March 28. But the plotters had overlooked the society, whose Sachems, being either in, or subservient to, the “ring,” now exercised the oft-used expedient of shutting out of the hall such persons as happened to be obnoxious to them. When the members of the general committee appeared before Tammany Hall, on the night of March 28, they found to their surprise that the “ring” had caused to be placed a guard of 600 policemen about the building, to prevent their ingress. The gathering convened in Irving Hall, nearby, where by roll call it was found that 187 members of the committee, later increased by about a dozen — a clear majority of the whole number — were present. Fiery speeches were made, and the set purpose of dethroning and repudiating the “ring” Sachems was emphatically declared.

But the Young Democracy failed to distribute among the members of the Legislature the sum promised, and the country members, by way of revenge, voted down the Huckleberry charter. Greatly encouraged by his enemies’ defeat, the “Boss” went to Albany with a vast sum of money and the draft of a new charter. This charter, supplemented by a number of amendments which Tweed subsequently caused the Legislature to pass, virtually relieved the “ring” of accountability to anybody. The State commissions were abolished, and practically the whole municipal power was placed in the hands of a Board of Special Audit, composed of himself, Connolly and Mayor Hall. No money could be drawn from the city without the permission of this board. The powers of the Board of Aldermen, moreover, were virtually abolished.[3]

The charter, which immediately became known as the “Tweed charter,” was passed on April 5. The victory cost every dollar of the sum Tweed took with him. Samuel J. Tilden testified that it was popularly supposed that about $1,000,000 was the amount used.[4] Tweed stated that he gave to one man $600,000 with which to buy votes, this being merely a part of the fund. For his services this lobbyist received a position requiring little or no work and worth from $10,000 to $15,000 a year.[5] Tweed further testified that he bought the votes of five Republican Senators for $40,000 apiece, giving one of them $200,000 in cash to distribute. The vote in the two houses was practically unanimous: in the Senate, 30 to 2, and in the Assembly, 116 to 5. The state of the public conscience in New York City may be judged from the fact that the charter received the support of nearly all classes, “large numbers,” according to the Annual Cyclopedia for 1871, “of the wealthiest citizens signing the petition” [for its passage].

Tweed’s enemies were now crushed. At the election (April 18) of the Sachems of the society the opposition could poll only a paltry 23 votes, against the 242 secured by Tweed’s candidates; and even this minority was a factitious one, Tilden declaring that Tweed had arranged for it, to furnish the appearance of a contest.

Tweed’s organization was wonderfully effective. The society stood ready at a moment’s notice to expel from the Wigwam any person or group obnoxious to him. The general committee was now likewise subservient. In every ward he had a reliable representative — a leader, whose duty was to see that his particular district should return its expected majority. Under the leaders there were sub-leaders, ward clubs and associations, and captains of every election district. The organization covered every block in town with unceasing vigilance, acquainting itself with the politics of every voter. The moment a leader lost his popularity, or hesitated at scruples of any sort, Tweed dismissed him; only vote-getters and henchmen were wanted. So large was his personal following, that he not only caused thousands to be appointed to superfluous offices, but had a number of retainers, to whom he paid in the aggregate probably $60,000 a year, “letting them think they were being paid by the city.”[7] Opposition he had no difficulty in buying off, as in the case of one “Citizen’s Association,” whose principal men he caused to be appointed to various lucrative positions in the city government.[8]

The Registry law having been virtually repealed at Tweed’s order, election frauds were made easier, and as a result of the abolition by the “Tweed charter” of the December city election, and the merging into one day’s polling of national, State and city elections, the “ring” was in a position to resume the old practise of trading candidates, if all other resources failed.

With the passage of the “Tweed charter” and the City and County Tax Levy bill[9] of 1870, the stealing expanded to a colossal degree. At a single sitting — on May 5, 1870 — the Board of Special Audit made out an order for the payment of $6,312,500 on account in building the new County Court House. Of this sum barely a tenth part was realized by the city.[10] From the 65 per cent levied on supplies, at the end of 1869, the rate was swelled to 85 per cent. “Jobs” significant of untold millions lurked in every possible form. Great projects of public improvements were exploited to the last dollar that could be drawn from them. A frequent practise of Tweed was to create on paper a fictitious institution, jot down three or four of his friends as officers, put a large amount for that institution in the tax levy and pocket the money. Asylums, hospitals and dispensaries that were never heard of, and never existed except on paper, were put down as beneficiaries of State and city. The thefts were concealed in the main by means of issues of stocks and bonds and the creation of a floating debt, which the Controller never let appear in his statements.

A new reform movement appeared during the Summer and Fall of 1870. Republicans, independents and disaffected Democrats combined forces and nominated Thomas A. Ledwith for Mayor. The reform ticket was apparently received with great public approval, and hopes began to be entertained of its success at the polls. Tweed, however, had already secured, by ways known best to himself, assurance of Republican assistance; he had large numbers of Republican officials, Election Inspectors, and the like, in his pay, and therefore knew that he had nothing to fear. Besides this, Tammany was united and enthusiastic. Its candidates, Hall, for Mayor, and Hoffman, for Governor, had seemingly lost none of their popularity with the rank and file. A few days before the election a popular demonstration, perhaps the largest in Tammany’s history, was held in and about the Wigwam. August Belmont presided, and addresses were made by Seymour, Hoffman, Tweed and Fisk (who had now become a Democrat). All the speakers were received with boisterous enthusiasm.

Tweed won, Hall receiving 71,037 votes, to 46,392 for Ledwith. But the indications were plain that a reaction against the “ring” had begun, for Hoffman’s vote exceeded that of Hall by 15,631, while Ledwith’s vote exceeded that of Stewart L. Woodford, the Republican candidate for Governor, by nearly 12,000.

Partly to quiet his conscience, it was suspected, and in part to make himself appear in the light of a generously impulsive man, Tweed gave, in the Winter of 1870-71, $1,000 to each of the Aldermen of the various wards to buy coal for the poor. To the needy of his native ward he gave $50,000. By these acts he succeeded in deluding the needier part of the population to the enormity of his crimes. Abstractly, these beneficiaries of his bounty knew he had not amassed his millions by honest means. But when, in the midst of a severe Winter, they were gladdened by presents of coal and provisions, they did not stop to moralize, but blessed the man who could be so good to them. Even persons beyond the range of his bounty have hailed him as a great philanthropist; and the expression, “Well, if Tweed stole, he was at least good to the poor,” is still repeated, and furnished, in its tacit exoneration, the prompting for like conduct, both thieving and giving, on the part of his successors.

One of Tweed’s schemes was the Viaduct Railroad bill, which virtually allowed a company created by himself to place a railroad on or above the ground, on any city street. The Legislature passed, and Governor Hoffman signed, the bill, early in 1871. One of its provisions authorized and compelled the city to take $5,000,000 of stock;[11] another exempted the company’s property from taxes or assessments, while other bills allowed for the benefit of the railroad the widening and the grading of streets, which meant a “job” costing the city from $50,000,000 to $65,000000.[12] Associated with Tweed and others of the “ring” as directors were some of the foremost financial and business men of the day. The complete consummation of this almost unparalleled steal was prevented only by the general exposure of Tweedism a few months later.

In the Assembly of 1871 party divisions were so even that Tweed, though holding a majority of two votes, had only the exact number (65) required by the constitution as a majority. In April “Jimmy” Irving, one of the city Assemblymen, resigned, to avoid being expelled for having assaulted Smith Weed. But Tweed was equal to the occasion, for the very next day he obtained the vote and services of Orange S. Winans, a Republican creature of the Erie Railroad Company. It was charged publicly that Tweed gave Winans $75,000 in cash, and that the Erie Railroad Company gave him a five-years’ tenure of office at $5,000 a year.[13]

Tweed neglected no means whatever to avert popular criticism. A committee composed of six of the leading and richest citizens — Moses Taylor, Marshall O. Roberts, E.D. Brown, J.J. Astor, George K. Sistare and Edward Schell — were induced to make an examination of the Controller’s books, and hand in a most eulogistic report, commending Connolly for his honesty and faithfulness to duty. So highly useful a document naturally Was used for all it was worth.[14]

But it was in his tender providence over the newspapers that his greatest success in averting public clamor was shown. Both in Albany and in this city he showered largess upon the press. One paper at the Capital received, through his efforts, a legislative appropriation of $207,900 for one year’s printing, whereas $10,000 would have overpaid it for the service rendered.[15] The proprietor of an Albany journal which was for many years the Republican organ of the State, made it a practice to submit to Tweed’s personal censorship the most violently abusive articles. On the payment of large sums, sometimes as much as $5,000, Tweed was permitted to make such alterations as he chose.[16] Here, in the city, the owner of one subservient newspaper received $80,000 a year for “city advertising,” and to some other newspapers large subsidies were paid in the same guise. Under the head of “city contingencies,” reporters for the city newspapers, Democratic and Republican, received Christmas presents of $200 each. This particular practice had begun before Tweed’s time,[17] but in line with the expansive manner of the “ring,” the plan was elaborated by subsidizing six or eight men on nearly all the city newspapers, crediting each of them with $2,000 or $2,500 a year for “services.”[18]

The proprietor of the Sun, a newspaper that, from supporting the Young Democracy, veered suddenly to an enthusiastic devotion to the “Boss,” proposed, in March, 1871, the erection of a statue to Tweed. The “Boss’s adherents jumped at the idea; and an association for the purpose was formed by Edward J. Shandley, a Police Justice, and a host of other men of local note, in professional, political and social circles, among whom were not only ardent friends of Tweed, but also those who, having opposed him, sought this opportunity of ingratiating themselves into his favor. The statue was to be “in commemoration of his [Tweed’s] services to the commonwealth of New York” — so ran the circular letter.

In a few days the association had obtained nearly $8,000, some politicians giving $1,000 apiece. Other men pledged themselves to pay any amount from $1,000 to $10,000, and were on the point of making good their word when a letter from Tweed appeared, discountenancing the project. It was printed in the Sun of March 14, 1871, under the heading :

“ A GREAT MAN’S MODESTY.THE HON. WILLIAM M. TWEED DECLINES THE SUN’ STATUE — CHARACTERISTIC LETTER FROM THE GREAT NEW YORK PHILANTHROPIST — HE THINKS THAT VIRTUE SHOULD BE ITS OWN REWARD — THE MOST REMARKABLE LETTER EVER WRITTEN BY THE NOBLE BENEFACTOR OF THE PEOPLE.”

“Statues,” wrote Tweed in part, “are not erected to living men, but to those who have ended their careers, and where no interest exists to question the partial tributes of friends.” Tweed hinted that he was not so deficient in common sense as not to know the bad effect the toleration of the scheme would have, and, ever open to suspicion, he broadly asserted that the original statue proposition was made either as a joke or with an unfriendly motive.

One of the signers of the circular has assured the author that it was a serious proposal. The attitude of the Sun confirms this. On March 15 that newspaper stated editorially that it thought “Mr. Tweed had acted hastily,” and inquired whether it was too late “to realize so worthy and so excellent an idea.” In the same issue appears an interview with Justice Shandley, who says :

“We had contemplated eventually making a public proposition that the testimonial finally take the form of the establishment of a grand charitable institution, bearing Mr. Tweed’s honored name, and so overcome the prejudices that the statue proposition have engendered, and passing the fame of that statesman, philanthropist and patriot down to future generations. Mr. Tweed has willed otherwise, and we must submit.”

A Chicago clergyman, reading of the suggestion, publicly declared that Tweed was “more dangerous than were the ancient robber kings.” Copying this expression, the Sun urged editorially on May 13 :

“Now, let the friends of Mr. Tweed combine together and answer this clergyman by erecting and endowing the Tweed Hospital in the Seventh Ward of this city. A great monument of public charity is the best response that can be made to such accusations.”

Tweed aimed at a high social place. He had removed from his modest house on Henry street to a pretentious establishment, on Fifth Avenue. His daughter’s wedding was among the marvels of the day; from her father’s personal and political friends she received nearly $100,000 worth of gifts. Among the wedding presents were forty complete sets of silver and fifteen diamond sets, one of which was worth $45,000. Her wedding dress cost $4,000, and the trimmings were worth $1,000.

All of his expenditures showed a like disregard of cost. In the construction of the stables adjoining his Summer place at Greenwich, Conn., money “was absolutely thrown away.” The stalls were built of the finest mahogany. All told, these stables were said to have cost $100,000.

The Americus Club was his favorite retreat, and there his satellites followed him. Scores of them were only too glad to pay the $1,000 initiation fee required, in addition to the $2,000 or so charged for sumptuously fitting the room to which each was entitled. The grandeur of their club badges well illustrated their extravagance. One style of the badges was a solid, gold tiger’s[19] head in a belt of blue enamel; the tiger’s eyes were rubies, and above his head sparkled three diamonds of enormous size. Another style of badge was of solid gold with the tiger’s head in papier-maché under rock crystal. It was surrounded by diamonds set in the Americus belt. Above was a pin with a huge diamond, with two smaller diamonds on either side. This badge was estimated to be worth $2,000.

A third style showed the tiger’s head in frosted gold, with diamond eyes. Everywhere the prodigal dissipation of the plunder was visible. Sums of a few thousand dollars Tweed professed to hold in utter contempt. A city creditor once appealed to him to use his influence with Controller Connolly to have a bill paid. Twenty times he had asked for it, the creditor said, and could get it only by paying the 20 per cent. demanded. (This 20 per cent., it should be explained, was the sum extorted from all city creditors by the officials in the Controller’s office as their portion after the chiefs of the “ring” had taken the lion’s share.) Tweed looked at the man a moment and then wrote hastily to Connolly :

“Dear Dick : For God’s sake pay ——’s bill. He tells me your people ask 20 per cent. The whole d——d thing isn’t but $1,100. If you don’t pay it, I will. Thine. William M. Tweed.”

The “Boss’s” note being virtually a command, the bill was paid in full.

CHAPTER XXV

Collapse and Dispersion of

Collapse and Dispersion of

the “ Ring ”

1871-1872

1871-1872

THE downfall of the “ring” was inevitable. No such stupendous series of frauds could reasonably be expected to continue, once the proper machinery for their exposure and for the awakening of the dormant public conscience was put in motion. Protests and complaints and even concerted opposition might for the time prove futile, as indeed they did; but the wind had been sown for the reaping of the whirlwind, and it could not be averted. One conspicuous instance of apparently futile criticism of the “ring” was the action of the New York City Council of Political Reform. This body, but recently organized, held a mass-meeting in Cooper-Union, April 6, 1871, to consider “the alarming aspects of public affairs generally,” and to agree upon means for arousing the, public to some remedial action. Speeches were made by Henry Ward Beecher, Judge George C. Barrett, William F. Havemeyer, William Walter Phelps and William M. Evarts. It was pointed out that the city debt had increased from about $86,000,000 in 1868 to over $186,000,000 at the close of 1870. But amazing as were the facts, the meeting produced no direct effect.

The immediate causes of the exposure were fortuitous and accidental. In December, 1870, Watson, who had become one of the chiefs in the Finance Department, was fatally injured while sleigh-riding, and died a week later. In the resultant change, Stephen C. Lyons, Jr., succeeded Watson, and Matthew J. O’Rourke succeeded Lyons as County Bookkeeper. Mr. O’Rourke gradually came upon the evidence of the enormous robberies. In the meantime some of the evidence had also come into the possession of James O’Brien, one of the Young Democracy leaders. Controller Connolly was on the point of paying out the $5,000,000 called for by the Viaduct Railroad act, as well as other sums, but learning of O’Brien’s knowledge of the situation, resolved to defer the payments. In the Summer of 1871 Mr. O’Rourke presented his evidence to the New York Times.

This newspaper published the figures in detail, producing fresh disclosures day after day, and showing indisputably that the city had been plundered on a stupendous scale. In two instances alone — in the printing bills and the bills for the erection and repairing of the County Court House — the Times averred that over $10,000,000 had been illegally squandered. Tweed had bought an obscure sheet, the Transcript, and had made it the official organ for city and county advertising. He had also formed the New York Printing Company, which not only did the city printing, but claimed the custom of many persons and corporations whom he was in a position either to aid or injure. These two properties served as the highly useful media with which to extort millions from the city treasury.

The Times gave the incontestable figures, disclosing that the sum of nearly $3,000,000 was squandered for county printing, stationery and advertising during the years 1869, 1870 and 1871.

But the new County Courthouse, the Times demonstrated, was the chief means of directly robbing the city. All told, so far as could be learned, the sum of $5,500,000 had been spent for “repairs” in thirty-one months — enough, the Times said, to have built and furnished five new buildings such as the County Court House. Merely the furnishing, repairing and decorating of this building, it was shown, cost $7,000,000. One firm alone — Ingersoll & Co. — received, in two years, the gigantic sum of $5,600,000 “for supplying the County Court House with furniture and carpets.” In brief, the County Court House, it was set forth specifically, instead of costing between $3,000,000 and $5,000,000, as the “ring” all along had led the public to believe, had actually cost over $12,000,000, the bulk of which was stolen.

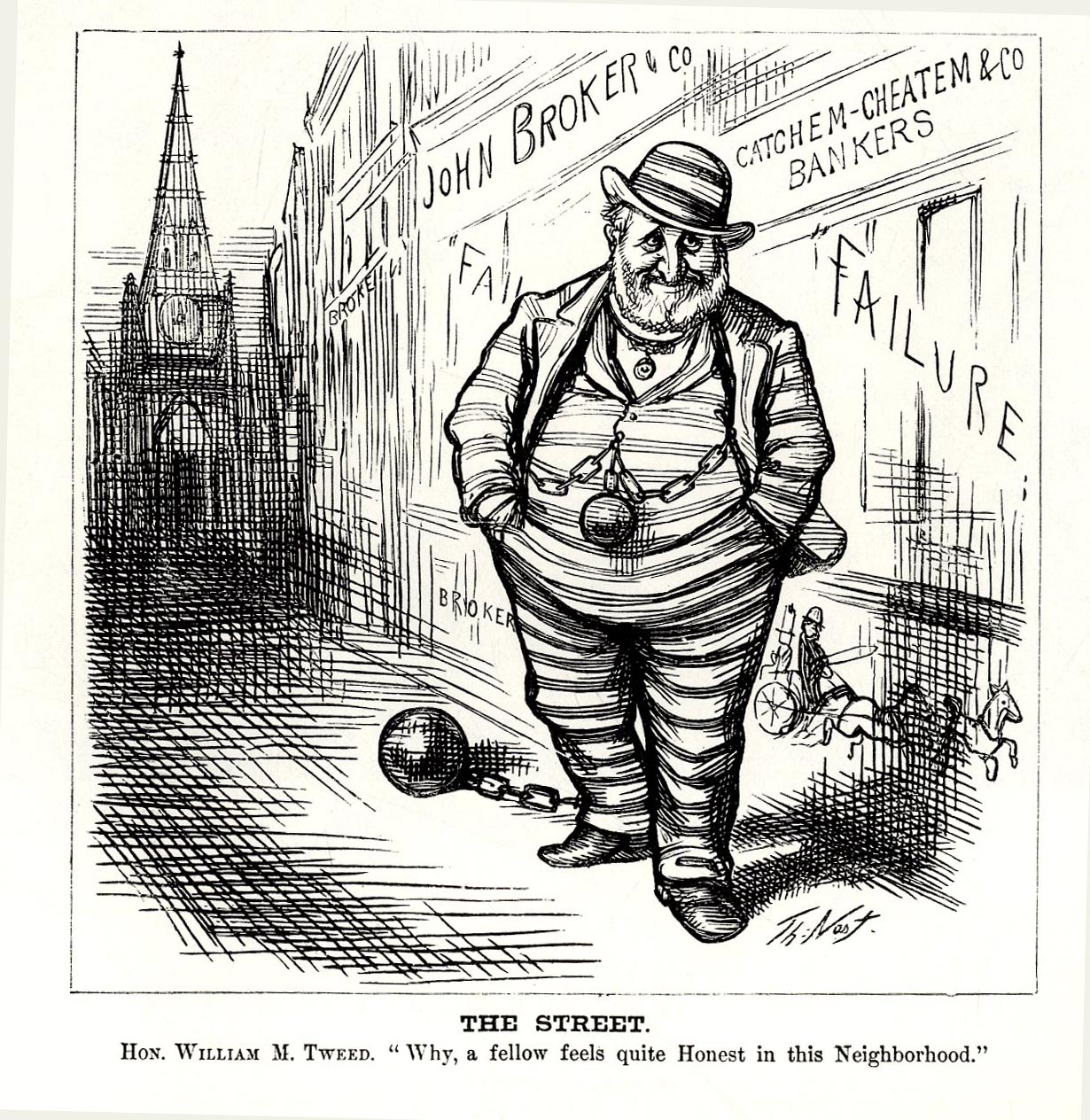

The members of the “ring” affected an air of unconcern regarding the disclosures. When Tweed was questioned as to the charges, he made his famous reply: “What are you going to do about it ?” He professed not to care for newspaper attacks. Yet Thomas Nast’s terribly effective cartoons pierced him to the heart. “If those picture papers would only leave me alone,” he lamented, “I wouldn’t care for all the rest. The people get used to seeing me in stripes, and by and by grow to think I ought to be in prison.” Mayor Hall put on an air of jocose indifference, occasionally replying to the charges by references to the alleged frauds in the Federal Government,[1]but oftener by wondrously facetious jests such as: “Counts at Newport are at a discount”; “shocking levity — the light-ship off Savannah has gone astray”; “these warm, yet occasionally breezy days, with charmingly cool mornings and evenings, are an indication that we are likely to have what befell Adam — an early Fall.”[2]

The public, however, was at last aroused, and the impudent flippancy of Tweed, Hall and others only added to the public indignation. Though the Times was but imperfectly armed with proofs, each day’s revelations brought the citizens to a keener realization of the unprecedented enormity of the thefts, and the resolve was made by leading members of both parties in the city to unite and crush the “ring.” A call for a mass-meeting, to be held in Cooper Union, September 4, was met by a tremendous outpouring of citizens. William F. Havemeyer, the former Mayor, presided, and 227 vice-presidents and 15 secretaries were chosen from among the foremost names in the community. Among the speakers were Robert B. Roosevelt and Judge Edwards Pierrepont. Now, for the first time, the public obtained a really definite idea of the magnitude of the sum stolen by the “ring” and its followers. Resolutions were reported by Joseph H. Choate, stating that the acknowledged funded and bonded debt of the city and county was upward of $113,000,000 — over $63,000,000 more than it was when Mayor Hall took office — and that there was reason to believe that there were floating, contingent or pretended debts and claims against the city and county which would amount to many more millions of dollars, and which would be paid out of the city treasury unless the fiscal officers were removed and their proceedings arrested. The resolutions concluded by directing the appointment of an Executive Committee of Seventy, to overthrow the “ring,” abolish abuses, secure better laws, and by united effort, without reference to party, obtain a good government and honest officers to administer it.

The first move decided upon by the Committee of Seventy was to make a thorough examination of the city’s accounts. A sub-committee was on the point of doing this when, on the morning of September 11, it was reported that the Controller’s office, in the City Hall, had been broken into on the previous night and the vouchers, more than 8,500 in all, stolen. The “ring” confederates pretended that the vouchers had been abstracted from a glass case — an absurd explanation considering that after spending $400,000 for safes the city officials should have chosen such a flimsy receptacle. Later, the charred remains of these vouchers were discovered in an ash-heap in the City Hall attic.

As if to yield to public opinion, Mayor Hall at once asked Connolly to resign as Controller. Connolly refused, on the ground that such a step without impeachment and conviction on trial would be equal to a confession of guilt. Secretly, however, fearing that the other members of the “ring” intended to make a scapegoat of him, he was disposed to make terms with the Committee of Seventy to save himself. Upon the advice of Havemeyer, he appointed Andrew H. Green, Deputy Controller. With Mr. Green in that post, the Committee of Seventy could expect a tangible computation of the “ring’s” thefts. Alive to their danger, the other members of the “ring” in terror tried to force Connolly to resign, so as to end the powers he had delegated to the new Deputy Controller. Mayor Hall insisted that in making Mr. Green Acting Controller, Connolly’s action was equivalent to a resignation, and with much bluster said he would treat it as such.

In October the sub-committee made a hasty examination of such of the city accounts as were available, and were enabled to report that the debt of the city was doubling every two years; that $3,200,000 had been paid for repairs on armories and drill rooms, the actual cost of which was less than $250,000; that over $11,000,000 had been charged for outlays on the unfinished County Court House,[3] the entire cost of building which, on an honest estimate, would be less than $3,000,000; that safes, carpets, furniture, cabinet-work, painting, plumbing, gas and plastering, had cost $7,289,466, the real value of which was found to be only $624,180; that $460,000 had been paid for $48,000 worth of lumber; that the printing, advertising, stationery, etc., of the city and county had cost in two years and eight months, $7,168,212; that a large number of persons were on the payrolls of the city whose services were neither rendered nor needed; and that figures upon warrants and vouchers had been altered fraudulently and payments made repeatedly on forged endorsements.

These figures, though presenting nothing more than an outline of the immensity of corruption, gave the Committee of Seventy a foundation upon which to proceed legally. It at once obtained an injunction from Judge Barnard, restraining for the time the payment of all moneys out of the city treasury.[4] The order was modified subsequently to permit the necessary payments. The city treasury had been sacked so completely that it was found necessary to borrow nearly a million dollars from the banks to satisfy the more pressing claims.

The Committee of Seventy next presented Mayor Hall before the Grand Jury for indictment Anticipating this, the “ring” had “packed” the Grand Jury; but such was the public outcry on this fact becoming known, that Judge Barnard was forced to dismiss the jury and order a new panel. The second jury, however, did not indict the Mayor, giving, as a reason, the lack of conclusive evidence. Later, Hall was tried, but the jury disagreed. The Committee of Seventy next procured the appointment of Charles O’Conor as assistant to the Attorney-General, and then engaged, as O’Conor’s assistants, William M. Evarts, Wheeler H. Peckham and Judge Emmott, with the express view of driving the “ring” men into prison. Through their energy, Tweed was arrested, on the affidavit of Samuel J. Tilden, on October 26, and held to bail in the sum of $1,000,000.

But Tweed was not yet crushed. In a few days — on November 7 — an election for members of the Legislature, State officers, Judges of the Supreme Court, and Aldermen and Assistant Aldermen, was to be held. Most of the “ring” men, in the very face of the revelations of their stupendous thefts, forgery, bribing and election frauds, came forward as candidates for renomination and election. Once elected, they reckoned upon their “vindication.” The Committee of Seventy naturally aimed at the defeat of the Tammany candidates, both for political and moral effect, and placed candidates in the field for all local, legislative and judicial offices.

As Grand Sachem and chairman of the Tammany General Committee, Tweed was still “boss.” He arranged to win by his oft-used weapons of bribery and intimidation, if not by violence. The two Republican Police Commissioners were his hirelings, owing their offices to him. They could be depended upon to aid their Tammany colleagues into making the police a power for his benefit. How well, otherwise, the “ring” was fortified, was shown when the Times[5] charged that sixty-nine members of the Republican General Committee, which assumed to direct the counsels of the Republican party in the city, were stipendiaries of Tweed and Sweeny. One of them was quoted as saying, “I go up to headquarters the first of every month and get a hundred dollars, but I don’t hold no office and don’t do no work.”

Tammany feigned to regard Tweed as a great benefactor being hounded. Tweed carried out the comedy to his best. On September 22 a “great Tweed mass-meeting” assembled in “Tweed Plaza.” Resolutions were vociferously adopted, that,

“pleased with his past record and having faith in his future, recognizing his ability and proud of his leadership, believing in his integrity and outraged by the assaults upon it, knowing of his steadfastness and commending his courage, admiring his magnanimity and grateful for his philanthropy, the Democracy of the Fourth Senatorial District of the State of New York, constituents of the Hon. William M. Tweed, in mass-meeting assembled, place him in nomination for re-election, and pledge him their earnest, untiring and enthusiastic support.”[6]

Despite the public agitation over the frauds, the Tammany nominations were of the worst possible character. Nominees for the State Senate included such “ring” men as Genet, “Mike” Norton, John J. Bradley and Walton; and for the Assembly, “Jim” Hayes, an unscrupulous tool; “Tom” Fields, reputed to be probably the most corrupt man that ever sat in the Legislature; Alexander Frear, who for years had engineered “ring” bills; and “Jimmy” Irving, who had been forced to resign his seat in the Assembly the previous Winter to avoid being expelled for a personal assault on a fellow-member. The innumerable Tammany ward clubs, all bent on securing a share of the “swag,” paraded and bellowed for these characters.

The election proved that the people had really awakened. The victory of the Committee of Seventy was sweeping. Of the anti-Tammany candidates, all of the Judges, four of the five Senators, 15 of the 21 Assemblymen, and all but two of the Aldermen were elected, and a majority of the Assistant Aldermen had given pledges for reforms.

The one Tammany candidate for Senator elected was the “Boss” himself, and he won by over 9,000 majority. The frauds in his district were represented by careful observers as enormous. In many precincts it was unsafe to vote against him. Opposing voters were beaten and driven away from the polls, the police helping in the assaults. The reelection of Tweed, good citizens thought, was the crowning disgrace, and measures were soon taken which effectually prevented him from taking his seat.

On November 20 Connolly resigned as Controller, and Andrew H. Green was appointed in his place. On November 25 Connolly was arrested and held in $1,000,000 bail. Unable to furnish it, he was committed to jail. On December 16 Tweed was indicted for felony. While being taken to the Tombs he was snatched away on a writ of habeas corpus and haled before Judge Barnard, who released him on the paltry bail of $5,000. A fortnight later, forced by public opinion, Tweed resigned as Commissioner of Public Works, thus giving up his last hold on power.

The careers of the “ring” men after 1871 form a striking contrast to their former splendor. Tweed ceased to be Grand Sachem. Almost every man’s hand seemed raised against him. The newspapers which had profited most by his thefts grew rabid in denouncing him and his followers, and urged the fullest punishment for them.

He was tried on January 30, 1873. The jury disagreed. During the next Summer he fled to California. Voluntarily returning to New York City, against the advice of his friends, he was tried a second time, on criminal indictments, on November 19. Found guilty on three-fourths of the 120 counts, Judge Noah Davis sentenced him to twelve years’ imprisonment and to pay a fine of $12,000. Upon being taken to Blackwell’s Island, the Warden of the Penitentiary asked him the usual questions: “What occupation?” “Statesman!” he replied. “What religion?” “None.”

After one year’s imprisonment, Tweed was released by a decision of the Court of Appeals, on January 15, 1875, on the ground that owing to a legal technicality the one year was all he was required to serve. Anticipating this decision, Tilden and his associated had secured the passage of an act by the Legislature, expressly authorizing the People to institute a civil suit such as they could not otherwise maintain. New civil suits were then brought against Tweed, and as soon as he was discharged from the Penitentiary he was rearrested and held in $3,000,000 bail.

This bail he could not get, and he lay in prison until December 4, when, while visiting his home, in the custody of two keepers, he escaped. For two days he hid in New Jersey, and later was taken to a farm-house near the Palisades. He disguised himself by shaving his beard and clipping his hair, and wearing a wig and gold spectacles. Fleeing again, he spent a while in a fisherman’s hut near the Narrows, visiting Brooklyn and assuming the name of “John Secor.” Leaving on a schooner, he landed on the coast of Florida, whence he went to Cuba in a fishing smack, landing near Santiago de Cuba. The fallen “Boss” and a companion were at once arrested as suspicious characters — the Ten Years’ War being then in progress — and Tweed was recognized. He, however, smuggled himself on board the Spanish bark Carmen, which conveyed him to Vigo, Spain. Upon the request of Hamilton Fish, Secretary of State, he was arrested and turned over to the commander of the United States man-of-war Franklin, which brought him back to New York on November 28, 1876.

In one of the civil suits judgment had been given against him for over $6,000,000. Confessing to this, he was put in jail, to be kept there until he satisfied it, a requirement he said he was unable to meet. The city found no personal property upon which to levy. Tweed testified in 1877 that he held about $2,500,000 worth of real estate in 1871, and that at no time in his life was he worth more than from that amount to $3,000,000.[7] He had recklessly parted with a great deal of his money, he stated. He testified also to having lost $600,000 in two years in fitting up the Metropolitan Hotel for one of his sons,[8] and to having paid his lawyers $400,000 between 1872 and 1875. His escape from Ludlow Street Jail had cost him $60,000. It is reasonably certain that he had been blackmailed on all sides, and besides this, as has already been shown, he had been compelled to disgorge a vast share of the plunder to members of the Legislature and others. When his troubles began he transferred his real estate — and, it is supposed, his money — to his son, Richard M. Tweed.

In Ludlow Street Jail he occupied the Warden’s parlor, at a cost of $75 a week. As he lay dying, on April 12, 1878, he said to the matron’s daughter: “Mary, I have tried to do good to everybody, and if I have not, it is not my fault. I am ready to die, and I know God will receive me.” To his physician, Dr. Carnochan, he said: “Doctor, I’ve tried to do some good, if I haven’t had good luck. I am not afraid to die. I believe the guardian angels will protect me.” The matron said he never missed reading his Bible. According to S. Foster Dewey, his private secretary, Tweed’s last words were: “I have tried to right some great wrongs. I have been forbearing with those who did not deserve it. I forgive all those who have ever done evil to me, and I want all those whom I have harmed to forgive me.” Then throwing out his hand to catch that of Luke, his black attendant, he breathed his last.

Only eight carriages followed the plain hearse carrying his remains, and the cortege attracted no attention. “If Tweed had died in 1870,” said the cynical Coroner Woltman, one of his former partizans, “Broadway would have been festooned with black, and every military and civic organization in the city would have followed him to Greenwood.”

Sweeny settled with the prosecutor for a few hundred thousand dollars and found a haven in Paris, until years later he reappeared in New York. He lived to an old age. The case of the People against him was settled -- as the Aldermanic committee appointed in 1877 to investigate the “ring” frauds reported to the Common Council — “in a very curious and somewhat incomprehensible way.”[9] The suits were discontinued on Sweeny agreeing to pay the city the sum of $400,000 “from the estate of his deceased brother, James M. Sweeny.” What the motive was in adopting this form the committee did not know. The committee styled Sweeny “the most despicable and dangerous of the “ring” because the best educated and most cunning of the entire gang.”[10]

Connolly fled abroad with $6,000,000, and died there. Various lesser officials also fled, while a few contractors and officials who remained were tried and sent to prison, chiefly upon the testimony of Garvey, who turned State’s evidence, and then went to London. Under the name of “A. Jeffries Garvie,” he lived there until his death in 1897.

Of the three Judges most involved — Barnard, Cardozo and McCunn[11] the first and the last were impeached, while Cardozo resigned in time to save himself from impeachment.

The question remains: How much did the “ring” steal ? Henry F. Taintor, the auditor employed in the Finance Department by Andrew H. Green to investigate the controller’s books, testified before the special Aldermanic committee, in 1877, that he had estimated the frauds to which the city and county of New York had been subjected, during the three and a half years from 1868 to 1871, at from $45,000,000 to $50,000,000.[12] The special Aldermanic committee, however, evidently thought the thefts amounted to $60,000,000; for it asked Tweed whether they did not approximate that sum, upon which he gave no definite reply. But Mr. Taintor’s estimate, as he himself admitted, was far from complete, even for the three and a half years. It is the generally accepted opinion among those who have had the best opportunity for knowing, that the sums distributed among the “ring” and its allies and dependents amounted to over $100,000,000.

Matthew J. O’Rourke, who, since his disclosures, made a further remarkable study of this special period, informed the author that, from 1869 to 1871, the “ring” stole about $75,000,000, and that he thought the total stealings from about 1865 to 1871, counting vast issues of fraudulent bonds, amounted to $200,000,000. Of the entire sum stolen from the city only $876,000 was recovered.

The next question is: Where did all this money go ? We have referred to the share that remained to Tweed and Connolly, but the other members of the great “ring” and its subordinate “rings” kept their loot, a few of them returning to the city a small part by way of restitution. When Garvey died in London, his estate was valued at $600,000.

next

Tammany Rises from the Ashes

1 Statement of Rev. Dr. H.W. Billings, in Cooper Union, April 6, 1871.

2 Testimony Senate Committee on Cities, 1890, Vol. II, pp. 1711-12.

3 The amendments to the charter of 1857 had abolished the Board of Councilmen and reinstituted the Board of Aldermen and the Board of Assistant Aldermen, the two constituting the Common Council. The “Tweed charter” continued these two boards, legislating the then incumbents out of office, and ordering a new election in May. The “ring,” of course, secured a large majority in this new Council.

4 The Tweed Case, etc., Supreme Court, 1876, Vol. II, p. 1212.

5 Document No. 8, p. 73.

6 Ibid., pp. 84-92.

7 Document No. 8, p. 212.

8 Ibid., pp. 223-25.

9 For the passage of this bill Tweed paid “in the neighborhood of $50,000 or $100,000.” Document No. 8, p. 154.

10 While this was going on Tweed maintained the most benevolent attitude in public. At the Fourth of July celebration in the Wigwam he “called the vast assemblage to order, and with coolness, but delighting (sic) modesty, welcomed brothers and guests.” Celebration at Tammany Hall of the 94th Anniversary, etc., by the Tammany Society or Columbian Order. Published by order of the Tammany Society, 1870.

11 Senate Journal, 1871, pp. 482-83.

12 See A History of Public Franchises in New York City, by Gustavus Myers.

13 Winans was unfortunate in his bargain, for after rendering the service agreed upon, his employers failed to keep their promises. Tweed gave him only one-tenth of the sum promised, and the Erie Railroad Company gave him no office, nor, so far as can be learned, any compensation whatever.

14 John Foley stated to the author that the six members of this committee were intimidated into making this report under the threat that the city officials would raise enormously the assessments on their very considerable holdings of real estate.

15 Document No. 8, pp. 215-18.

16 Ibid.

17 It was city money which the reporters frequenting the City Hall and court buildings received. The Aldermen passed in 1862 a resolution giving them (sixteen in all) $200 apiece, for “services.” Mayor Opdyke vetoed the resolution, but it was passed over his veto. (Proceedings of the Board of Aldermen, 1862, Vol. LXXXVIII, p. 708.) The grant was made yearly thereafter.

18 Statement of Mr. Foley.

19 The tiger as the symbolic representation of Tammany Hall doubtless dates from this time. This animal was the emblem of the Americus Club, and in Mr. Nast’s cartoons it frequently appears, with the word AMERICUS on its collar. In all probability Mr. Nast was responsible for the transference of the symbol from the club to the organization. The author has been unable to find any earlier reference to the Tammany tiger.

1 New York Times, August 29, 1871.

2 Ibid., August 30, 1871.

3 Later estimates put the expenditures on the Court House at $13,000,000. The generally accepted figures were over $12,000,000.

4 It was John Foley who procured the injunction. Mr. Foley later informed the author that upon the original injunction being obtained, the “ring” made a great clamor about the thousands of laborers who would be deprived of their wages, and ordered their hired newspaper writers so to incite the workingmen that the chief movers against the “ring” would be mobbed. In fact, were it not for public protection, grudgingly given on demand, it is doubtful whether some of the opponents of the “ring” would have survived the excitement.

5 August 19, 1871.

6 New York Times, November 2, 1871.

7 Document No. 8, p. 306.

8 Document No. 8, p. 372.

9 Document No. 8, p. 29.

10 Ibid., p. 30.

11 Barnard and Cardozo were both Sachems. Mr. Foley is the author’s authority for the statement that when Barnard died, $1,000,000 in bonds and cash was found among his effects.

12 Document No. 8.

No comments:

Post a Comment