The Heart of Everything That is,The Untold Story of Red Cloud,

An American Legend

28

ROUGHING

IT

Colonel Carrington’s

debriefing of his detail

commanders, the newly

arrived officers, and the

civilian wagon masters gave a

sense of urgency to

completing the fort. Red

Cloud, unlike his Indian

predecessors, not only was

qualified to plan and carry out

multiple and simultaneous

engagements, but encouraged

his raiding parties to employ

different tactics for each. His

warriors, for instance, had

ambushed the reinforcement

train directly, but had

attacked the first military

freight column by using

decoys to lure the flanking

soldiers away and then falling

on the main body of wagons.

The raids on the civilian

trains had been a combination

of the two strategies. Each

wagon master reported

having been approached by

Indians who either signed

peaceful intentions or flew

flags indicating as much. The

leaders had ridden out to

parley with them, even

presenting small gifts of

tobacco and the like. With the

Americans’ guard down, the

Indians had opened fire at a

signal as painted fighters

poured down from stands of

timber, up out of hidden

gullies, and out from behind

rolling buttes.

Who knew what Red

Cloud would try next? It was

best, Carrington noted, to

have a stockade to fight from.

Lieutenant Templeton’s detail

had carried with it a steam powered sawmill from Fort

Laramie, and Carrington

organized all able bodies into

dawn-to-dusk work and

escort details. No freight

wagons left for the pinery

blockhouses, the river, or the

hayfields in the little valley

on the other side of Lodge

Trail Ridge without a

mounted armed guard. Within

a week four log walls

completely encased the little

compound, and over 600,000

feet of four-inch plank boards

and shingles were piled high

next to foundations dug for

work sheds, living quarters,

and warehouses. Two

blockhouses with multiple

gun portals were also

constructed on Piney Island.

The new sawmill was

equipped with a steam

whistle, which the men found

useful for sounding alarms.

They were needed. The two

logging camps came under

serial sniping, to the point

where no man even relieved

himself without an escort.

Indians were not the only threat. Post butchers had begun slaughtering a few beef cattle for meat to be salted for winter, and the discarded offal drew packs of ravenous timber wolves by the score that circled the fort at night, their snarls and howls as frightening as a war cry. At first the sentries shot at the animals, but Colonel Carrington ordered the practice halted to conserve ammunition. His troopers were down to less than sixty rounds per man. The Indians noticed the change in this habit. One night a brave sheathed in a wolf pelt crawled to within a few feet of a lookout pacing a bastion and shot him dead. Soldiers on guard duty resumed firing at pretty much anything that moved in the night.

Despite the perilous environment the photographer Glover acted almost as if he were in an enormous garden laid out to his specifications. During the sweltering days he traversed the ocher buttes and ridgelines that shimmied beneath a blue dome so vast as to seem an illusion, lugging his camera equipment, overwhelmed by the striking vistas. He even ventured into the Rocky Mountains alone for days at a time with no weapon except a large Bowie knife he had picked up along the trail. He returned complaining of his inability to photograph at night, when silver moonlight bathed the snowcaps of 13,000-foot Cloud Peak, the highest of the Bighorns. Colonel Carrington warned him against such recklessness but Glover replied that with his long hair the Indians would surely take him for a Mormon and leave him alone. What effect his appearance would have on a timber wolf or grizzly bear he did not mention. When he was not out in the field he was a constant presence in and around Officers’ Row, joining the post wives in croquet matches on the mown parade ground or regaling them with tales from the salons of Philadelphia’s Main Line.

There is no record of what Carrington thought of the photographer’s antics. In any case, he had more pressing problems. He had finally received a dispatch from General Cooke stating that he could expect no more reinforcements until sometime in the fall. At the same time the War Department remained anxious over the lack of forts farther up the Bozeman Trail. Carrington was in a bind. He had already sent another infantry company south to buttress the garrison at Reno Station. The thought of losing two more of his remaining six to erect a third outpost seemed foolish. His thin blue line would be stretched well over 100 miles before Red Cloud finally snapped it. Carrington’s fear led him to make a risky decision—he bypassed the chain of command and wrote directly to the adjutant general in Washington, outlining his predicament and requesting assistance. Perhaps to soften this breach of military protocol he also wrote a long report to General Cooke, to be carried by the same mail courier. In it he took what he hoped was a more conciliatory tone.

“Character of Indian affairs hostile, ” he began. “The treaty does not yet benefit this route.” He then vowed, “The work is my mission here, and I must meet it, ” before reiterating the long list of grievances he had been filing since his arrival at Fort Laramie. How could he be expected to build forts and fight Indians and safeguard over 500 miles of the Bozeman Trail with so few resources? His horses were weak from consuming nothing but hay, his weapons were outdated, his ammunition was rationed, his best officers were being recalled, his infantrymen could barely ride, the emigrant trains were led by civilians who refused to heed his decrees, and he was acting not only as his own engineer and construction-gang boss but as a military strategist and tactician against an exceedingly shrewd enemy who picked off his men and his stock in small daily engagements yet refused to come out and fight a proper battle. “I must do all this, however arduous, ” he concluded, “and say I have not the men.”

This was all true. The War Department had never developed any formal doctrine for dealing with a guerrilla insurgency, let alone codified it in a written guide for frontier officers. Yet however much Carrington believed he was merely stating the obvious, to the battle-tested generals who read his report he seemed to be whining and unprofessional. Rather than attempt to learn as much about their enemy as possible, Carrington’s superiors, like the long, sad succession of Indian-fighting soldiers before them, were instead content to imagine what they would do if they were Red Cloud. It would be another ten weeks before Captain Fetterman was sent west to straighten out this mess, but by then official ignorance had already doomed Carrington’s command.

Indians were not the only threat. Post butchers had begun slaughtering a few beef cattle for meat to be salted for winter, and the discarded offal drew packs of ravenous timber wolves by the score that circled the fort at night, their snarls and howls as frightening as a war cry. At first the sentries shot at the animals, but Colonel Carrington ordered the practice halted to conserve ammunition. His troopers were down to less than sixty rounds per man. The Indians noticed the change in this habit. One night a brave sheathed in a wolf pelt crawled to within a few feet of a lookout pacing a bastion and shot him dead. Soldiers on guard duty resumed firing at pretty much anything that moved in the night.

Despite the perilous environment the photographer Glover acted almost as if he were in an enormous garden laid out to his specifications. During the sweltering days he traversed the ocher buttes and ridgelines that shimmied beneath a blue dome so vast as to seem an illusion, lugging his camera equipment, overwhelmed by the striking vistas. He even ventured into the Rocky Mountains alone for days at a time with no weapon except a large Bowie knife he had picked up along the trail. He returned complaining of his inability to photograph at night, when silver moonlight bathed the snowcaps of 13,000-foot Cloud Peak, the highest of the Bighorns. Colonel Carrington warned him against such recklessness but Glover replied that with his long hair the Indians would surely take him for a Mormon and leave him alone. What effect his appearance would have on a timber wolf or grizzly bear he did not mention. When he was not out in the field he was a constant presence in and around Officers’ Row, joining the post wives in croquet matches on the mown parade ground or regaling them with tales from the salons of Philadelphia’s Main Line.

There is no record of what Carrington thought of the photographer’s antics. In any case, he had more pressing problems. He had finally received a dispatch from General Cooke stating that he could expect no more reinforcements until sometime in the fall. At the same time the War Department remained anxious over the lack of forts farther up the Bozeman Trail. Carrington was in a bind. He had already sent another infantry company south to buttress the garrison at Reno Station. The thought of losing two more of his remaining six to erect a third outpost seemed foolish. His thin blue line would be stretched well over 100 miles before Red Cloud finally snapped it. Carrington’s fear led him to make a risky decision—he bypassed the chain of command and wrote directly to the adjutant general in Washington, outlining his predicament and requesting assistance. Perhaps to soften this breach of military protocol he also wrote a long report to General Cooke, to be carried by the same mail courier. In it he took what he hoped was a more conciliatory tone.

“Character of Indian affairs hostile, ” he began. “The treaty does not yet benefit this route.” He then vowed, “The work is my mission here, and I must meet it, ” before reiterating the long list of grievances he had been filing since his arrival at Fort Laramie. How could he be expected to build forts and fight Indians and safeguard over 500 miles of the Bozeman Trail with so few resources? His horses were weak from consuming nothing but hay, his weapons were outdated, his ammunition was rationed, his best officers were being recalled, his infantrymen could barely ride, the emigrant trains were led by civilians who refused to heed his decrees, and he was acting not only as his own engineer and construction-gang boss but as a military strategist and tactician against an exceedingly shrewd enemy who picked off his men and his stock in small daily engagements yet refused to come out and fight a proper battle. “I must do all this, however arduous, ” he concluded, “and say I have not the men.”

This was all true. The War Department had never developed any formal doctrine for dealing with a guerrilla insurgency, let alone codified it in a written guide for frontier officers. Yet however much Carrington believed he was merely stating the obvious, to the battle-tested generals who read his report he seemed to be whining and unprofessional. Rather than attempt to learn as much about their enemy as possible, Carrington’s superiors, like the long, sad succession of Indian-fighting soldiers before them, were instead content to imagine what they would do if they were Red Cloud. It would be another ten weeks before Captain Fetterman was sent west to straighten out this mess, but by then official ignorance had already doomed Carrington’s command.

☁☁☁

As the troops in the Powder

River Country awaited the

arrival of the reinforcements

accompanying Captain

Fetterman, the disturbing

dispatches from the frontier

that were reaching the War

Department in Washington

turned from a trickle into a

flood. The reports, read

today, are all the more

disheartening for their terse

dispassion. From Captain Ten

Eyck’s journal:

July 29: A “citizen train” was

attacked by Indians near the

South Fork of the Cheyenne

and eight men were killed

and two injured. One of the

injured men later died from

his wounds.

August 6: A train captained

by an H. Merriam lost two

civilians killed by Indians

along the 236-mile trail

between Forts Laramie and

Phil Kearny. Later that night

another train traveling the

same route lost fifteen killed

and five wounded.

August 7: Indians made their

first concerted attack on the

wood train on the road from

Piney Island, killing one

teamster.

August 12: Indians raided a

civilian train near the

Powder, running off a large

stock of cattle and horses.

August 13: Indians attacked

the Piney Island wood train

again; no casualties were

sustained.

August 14: Indians killed two

civilians less than a mile

from Reno Station.

August 17: An Indian raiding

party entered Reno Station’s

corral and stole seventeen

mules and seven of the

garrison’s twenty-two horses.

September 8: Under cover of

lashing rain, Indians

stampeded twenty horses and

mules that belonged to a

civilian contractor who was

delivering barrels of ham,

bacon, hardtack, soap, flour,

sugar, and coffee to Fort Phil

Kearny.

September 10: Indians

returned and made off with

another forty-two mules

belonging to the same

contractor. While the raiders

led an Army patrol on a futile

chase, another band took

advantage of the post’s

weakened defenses to fall on

the battalion’s herd a mile

from the stockade and sweep

away thirty-three horses and

seventy-eight more mules.

September 12: An Indian war

party ambushed a hay mowing detail, killing three

and wounding six.

September 13: A combined

Lakota-Arapaho raiding

party, several hundred braves

in total, stampeded a buffalo

drove into the post’s cattle

herd grazing near Peno

Creek. Two pickets were

wounded; 209 head of cattle

were lost in the buffalo run.

September 14: Two privates

were killed by Indians, one

while attempting to desert

and the other after riding too

far ahead of a hay train.

Wolves made off with both

bodies. Two hay-mowing

machines were destroyed,

and a large quantity of baled

hay was burned.

September 22: The scalped,

stripped, and mutilated

bodies of three civilian

freighters returning from

Montana were discovered

eleven miles from the post.

This went on through

October and November until

it was evident even to the

Army leadership that in Red

Cloud the Indians had finally

found a war chief who could

coordinate and sustain an

effective military campaign

—“a strategic chief,

” in the

words of the historian Grace

Raymond Hebard,

“who was

learning to follow up a

victory, an art heretofore

unknown to the red men.”

Moreover, the Bozeman Trail

was an extraordinarily

vulnerable supply line; every

few miles offered an ideal

ridgeline, draw, or mesa from

which a small, swift war

party could harass a

cumbersome wagon train

with deadly accuracy. The

Indians’ knowledge of the

terrain was such that when

Army patrols were assembled

to chase them they would

vanish into countless coulees

and breaks. And when parties

of mounted Bluecoats did cut

off a large body of hostiles,

the engagement left their

supply wagons vulnerable to

secondary attacks, a tactic

that Red Cloud perfected.

As tales of the lawless,

bloody Bozeman trickled

back east, newspapers from

St. Louis to New York

eagerly published the stories.

Yet still the settlers and

miners came—individuals,

families, entire clans—drawn

by the vast swaths of free

land, by the mountains veined

with minerals, by the same

spirit of freedom that had

drawn their ancestors from

the sclerotic kingdoms of

Europe to the shores of the

New World. August 1866

was the high point of

emigration on the Oregon

Trail, with at least one wagon

train arriving per day at Fort

Phil Kearny; in a single day

the post’s adjutant registered

979 men, 32 women, and 26

children passing through,

while traveler upon traveler

noted in journals surprise and

delight at hearing the opening

strains of the regimental

band’s martial songs amid the

harsh, deadly environment.

Many emigrants were also

gratified to find women and

children living at the post.

Families meant civilization, if

only its razor-thin edge.

Yet despite the modicum

of familiarity, nothing could

prepare the easterners for the

difficulties of life at Fort Phil

Kearny. Unlike older and

more established posts such

as Fort Laramie—which

boasted a circulating library,

a regular amateur theater, and

an occasional white-gloved

ball—Fort Phil Kearny was

“roughing it” in the true sense

of the phrase. Under the

broiling summer sun the

stench of human and animal

sweat and dung hung over the

post like an illness. And with

the exception of

noncommissioned officers,

who were granted their own

small rooms within the

barracks, all enlisted men

lived in an open bay heated in

the winter with cast-iron

stoves. The fort’s buildings

were stifling in summer and

“breezy in winter,

” owing to

their construction of green

pine logs. As the logs and

boards shrank the gaps were

stuffed with sod, which was

blown away by a good wind,

and rain and snow—either

falling through the cracks or

dragged in on boots—turned

the dirt floors to carpets of

mud.

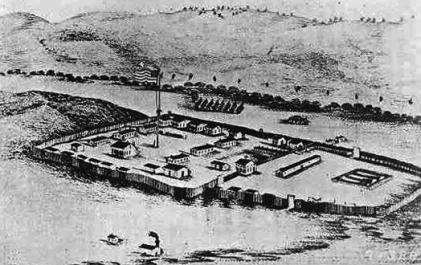

Fort Phil Kearny

The officers considered

their individual quarters

something of a step up,

although these quarters were

likely to horrify any women

who made the grueling trek

west. Along with Margaret

Carrington, ten other Army

wives had braved the journey

to the Powder River Country.

As the historian Shannon

Smith notes, it was they, and

in particular the officers’

wives (assumed to be more

educated and refined), who

often set the “civil” tone for

the small, isolated outpost.

Although this was her first

garrison, thirty-four-year-old

Margaret Carrington seemed

“to have been ideally suited

for the task of shaping the

community into a proper

Victorian settlement.” She

exuded a “commanding

presence, dignified in

deportment,

” and was

respected and well liked by

the other women. The eldest

of seven children, she tended

to treat the other wives more

as daughters than as friends,

organizing sewing circles to

fashion dresses and coats

from calico, flannel, and

linsey-woolsey—a coarse

twill with a linen warp and

woolen weft—purchased

from the sutler’s store. Nor

were the troopers themselves

immune to her enchantment,

and they presented her with

little gifts of wildflower

bouquets, armloads of extra

firewood, and plump rabbits

for stewing. She was the first

to inquire about the health of

soldiers’ families if word

reached her that someone

back east had fallen ill, and

almost every night she read to

the post’s children (and to

Old Gabe when he was on the

site).

Margaret Carrington was

also the fort’s social matron,

and before attacks on the

wood trains became a daily

occurrence she organized a

picnic on Piney Island in

celebration of the arrival of a

new sutler hauling fresh

vegetables “most precious

and rare.” It was a grand

affair, with fresh elk steaks

and salmon, canned lobster,

and tinned oysters garnished

with pineapples, tomatoes,

sweet corn, peas, and pickles.

Doughnuts, gingerbread, and

plum cakes were served for

dessert, followed by Havana

cigars for the men and

“Madame Clicquot” for those

who imbibed. It was the last

such affair. Soon enough

Colonel Carrington ordered

the closing of all gates to

anyone without specific

orders to venture outside, and

the women became virtual

prisoners in the stockade.

Margaret Carrington and the

others nonetheless attempted

to impart whatever small

“domestic casts” were

practical.

She showed the wives

along Officers’ Row how to

stretch canvas tarps across the

underside of their sod-packed

roofs as a screen against

infiltrating snakes and mice,

and how to sew burlap gunny

sacks together to create crude

carpets. She even suggested

that the weeks-old, and

sometimes months-old,

newspapers left behind by

passing emigrant trains could

be hung above unglazed

windows as shades—after

they were passed around and

read. A few of the women

hired off-duty soldiers with

carpentry experience to

fashion double bedsteads out

of pine and spruce boards,

which they fitted with

mattresses that were stuffed

with dried prairie grass. Even

these homey touches failed to

overcome the maddening

isolation and confinement,

particularly for the eleven

rambunctious children. But as

every adult at the fort

recognized, this situation was

far preferable to the

alternative.

29

A THIN

BLUE LINE

While Fort Phil Kearny may

have been gaining families, it

was fast losing men. In the

first week of August Colonel

Carrington finally gave in to

the War Department’s

increasingly insistent

dispatches and sent two

companies north to scout

positions for a fort on the

Bighorn. It would be named

in honor of the Mexican War

hero General C. F. Smith.

Bridger went along to guide

the expedition, but was

instructed to return as soon as

a suitable site was found.

Another scout-interpreter, Jim

Beckwourth, also rode with

the detail.

Beckwourth, the son of a

Virginia slaveholder and his

mulatto mistress, had come

west with his master in the

early 1800s, was granted his

freedom around the beginning

of the beaver-trapping frenzy,

and became one of the first

mountain men to scale the

Rockies. Since quitting the

trapping business he had

worked on and off for the

Army, and he may or may not

have been present at the Sand

Creek massacre. He boasted

that he had at least two Crow

wives somewhere up in the

ranges, and that the tribe

treated him as a chief.

Though Carrington suspected

there was more rooster than

Crow in Beckwourth’s tall

tales, he reasoned that if even

a portion of what the man

said was true, his in-laws

might have valuable

information about Red

Cloud’s location and plans.

Other than the bits of

intelligence gleaned from the

Cheyenne Black Bear weeks

earlier, the colonel had no

clue as to the Bad Face

chief’s disposition.

Not long after his two

companies marched north—

leading a long line of civilian

trains that had been awaiting

an escort into Montana—the

battalion was depleted of

even more troops when

Colonel Carrington was

forced to supply a personal

bodyguard to a visiting

brigadier general. The general

had been sent from Omaha

with a small cavalry detail to

inspect Army installations

along the Oregon and

Bozeman Trails, and he

arrived at Fort Phil Kearny on

August 27. Carrington was in

no position to deny his

request for an escort to the

nearly completed Fort C. F.

Smith, ninety-two miles away

on the Bighorn. Two days

later twenty-seven of

Carrington’s best mounted

infantry rode out as his

escort. Before departing the

general assured Carrington

that two companies of the 2nd

Cavalry were en route from

Kansas to reinforce his

shrinking garrison. Whether

he was mistaken or

misinformed, they never

arrived, although a smaller

detachment of the 2nd did

show up on September 4 as

escort for an Army

commissary train.

By early autumn the 2nd Battalion of the 18th Infantry Regiment was stretched to its limit. The wood trains to and from Piney Island required constant security details, and continuous daylight lookouts were stationed on top of the Sullivant Hills and Pilot Knob. These were in addition to regular distress calls from emigrant trains under attack. Colonel Carrington was like a chess player forced to begin his match with only eight pieces. His rolls at the fort were down to just under 350 officers and men—a fact he was certain Red Cloud knew as well as he. A few Crow Head Men had offered to lend braves to the Army to help kill their hereditary enemies, but Carrington was leery of their true intentions. Despite the successes of the Pawnee scout corps, like most officers of the era he felt that relying on Plains Indians to fight other Plains Indians would reflect negatively on his own capability. Instead he finally petitioned General Cooke to allow him to reraise the company of Winnebago scouts the Army had recalled to Omaha earlier in the spring. Their dispersal, after all, had been a sop to Sioux sensibilities. That was now pointless.

While Carrington awaited Cooke’s reply he gladly hired on at Army base pay any civilians passing through the territory who asked for work. One such man was a Nebraskan, James Wheatley, traveling with his nineteen year-old wife, Elisabeth, and two young sons. Wheatley feared that the High Plains winter would close in on his family before they could reach the Montana gold fields and requested permission to open a civilian mess outside the post’s front gates. Carrington quickly agreed, and even supplied the lumber for the crude restaurant. Wheatley owned a seven-shot Spencer repeating rifle; he proved a crack shot and his wife a wonderful cook. Their wayfarers’ inn with its nightly dinners of fresh antelope, buffalo, and venison steaks became a kind of clubhouse for the civilian scouts, laborers, and teamsters, who remained after dinner to nibble cheese and crackers, drink whiskey, and trade “vile jokes and curses so gloriously profane that awed bystanders gazed upward, expecting the heavens to crack open.”

The Wheatleys’ clientele grew when a party of forty gold miners arrived one day from Virginia City. Their leader was a frontiersman with nearly two decades of experience in the West who told Colonel Carrington that the Montana lodes were playing out. He and his men had decided to explore richer prospects along the Bighorn. But they were harassed by hostiles throughout their journey south—only two days earlier two of their number had been killed in an ambush on the Tongue—and they now wished to winter over at Fort Phil Kearny while contemplating their next move. Carrington welcomed them with open arms. Forty rugged and well-armed men with their own horses constituted nearly the equivalent of a trained cavalry company, a rarity on the frontier. 1

The miners pitched a tent city just across Big Piney Creek and the next morning reported to the quartermaster, Captain Brown, for work assignments. They proved their worth almost immediately. Four days later, dawn’s first light streaking Pilot Knob to the east threw into relief a war party of 200 mounted Indians on the crest of Lodge Trail Ridge. The warriors bellowed, brandished their spears and war clubs, and charged down the slope toward the miners’ camp. An officer’s wife, watching from the post’s battlements, recorded the fight in her diary: “Hardly three minutes had elapsed after they came into view before the smoke and crack of the miners’ rifles, out from the cottonwood brush that lined the banks of the creek, had emptied half a dozen warriors’ [saddles] and brought down three times as many ponies.” Colonel Carrington was so excited he ordered the regimental band rushed to the parade ground to strike up a rousing battle hymn as soldiers cheered the fighting miners from the fort’s walls.

The engagement was one of two that season that the colonel recorded as “victories.” The other occurred about a week later when a breathless rider galloped into the stockade shouting that his wagon train was under attack not far down the trail. Carrington, following an instinct, had begun saddling and bridling the best horses at reveille each morning. The forethought now paid off. A relief detail led by Captain Brown and Lieutenant Bisbee was out of the quartermaster’s gate within moments, joined by half a dozen miners. The Indians dispersed at the sight of the rescue party but not before stampeding the train’s cattle. Brown and his men chased the Indians and longhorns for ten miles before overtaking them. Perhaps valuing the beef more than their lives, for once the Indians stood and fought. Brown’s party dismounted, formed a skirmish line, and withstood three mounted charges. Before the Indians withdrew, the soldiers and miners killed at least five of them and wounded sixteen more. The detail, with one trooper nicked by an arrow, also recovered all of the wagon train’s stock.

The small victory was noteworthy in another way. For months the prairie had rippled with rumors of white men, old mountain men, fighting alongside the Indians. The gnarled trappers, apparently as troubled as the Natives by “civilization” seeping through the Powder River Country and climbing their beloved Rockies, were even said to have planned and led attacks on the civilian trains. After this particular skirmish Captain Brown reported to Colonel Carrington that the Indian charges on his lines appeared to have been orchestrated by a white man. He was dressed in Lakota garb and was missing several fingers on his right hand, and he had ridden down on the soldiers screaming curses in English. In the final foray he was shot off his horse, but two braves scooped up his limp body. Carrington put this together with an earlier report about a “white Indian” with missing fingers—Captain Bob North —heading raids on emigrant trains. In his official dispatch to Omaha he reported the death of this Captain North.2

While the colonel reported these “significant blows, ” General Sherman was midway through his second tour of the frontier. The general’s mood had swung again, thanks to Red Cloud, and cold fury replaced the amiable disposition he had shown four months earlier in Nebraska. During a layover at Fort Laramie he parleyed with several of the Sioux sub-chiefs who had signed the previous spring’s treaty. When they admitted that they could not always restrain their rash young braves from joining raiding parties, Sherman’s famous temper flared, his red whiskers seeming to bristle. He had heard too much of this excuse. Turning to his interpreters but pointing dramatically toward the Indians, he said, “Tell the rascals so are mine; and if another white man is scalped in all this region, it will be impossible to hold mine in.”

Sherman then penned a letter to Colonel Carrington making his instructions clear. “We must try to distinguish friendly from hostile and kill the latter. But if you or other commanding officers strike a blow I will approve, for it seems impossible to tell the true from the false.” Carrington barely had to read between the lines. The second-highest-ranking officer in the United States Army had just declared open season on all High Plains Indians, friend or foe. Such was the temper of his own troops that the order was hardly necessary.

A few days later three Piney Island woodcutters were ambushed in a thick section of forest. Two of the enlisted men escaped to the island’s blockhouse with minor wounds. They told of watching their fallen comrade, Private Patrick Smith, shot through with arrows and scalped. Incredibly, Smith had not been killed, and he crawled half a mile back to the American lines leaving a trail of blood behind him. He was rushed by ambulance to the fort, where he died. That night at mess, graphic stories spread of Smith’s death. Scalped alive. Left for dead with the skin hanging in strips from his forehead. Arrows deliberately aimed to wound rather than to kill. It was unusually bad timing when nine Cheyenne, professing friendship, rode up to the fort near twilight and Colonel Carrington granted them permission to camp on the Little Piney. Someone started a rumor that they were the same Indians who had killed Pat Smith. It spread rapidly through the barracks, with the troopers expressing the same conviction as Sherman: It is impossible to tell the true from the false.

The American conspirators waited until midnight before some ninety men crept from their bunks and scaled the post’s walls. But the same chaplain who had made the heroic ride from Crazy Woman Fork got wind of the lynching party and woke Colonel Carrington. Carrington roused Captain Ten Eyck, who in turn gathered an armed guard. They arrived just in time to prevent the massacre. The mob tried to scatter, but two shots from Carrington’s Colt froze them. The colonel and Captain Ten Eyck recognized among the crowd some of their best fighting men. They took a moment to confer and concluded that they could not afford to make any examples. To take the Indians’ side and risk alienating the troops was too risky. The post’s tiny guardhouse already held twenty-four prisoners, most of them caught deserting. The battalion was in fact averaging a desertion every other day, and harsh discipline meted out here would only spur more “gold runners.” Carrington ordered the Cheyenne away, gathered the angry soldiers, and settled for a “brief tongue lashing” before marching them back to their quarters. It must have crossed Colonel Carrington’s mind that had the decision to stop the killings been Sherman’s, the general may not have been so quick to intervene.

The colonel was still contemplating this incident when Bridger returned from Fort C. F. Smith. He and Beckwourth had met with the Crows, who told them that Red Cloud was camped along the headwaters of the Tongue not seventy miles away with about 500 lodges of Lakota, Arapaho, and a few Gros Ventres. This meant anywhere from 500 to 1,000 warriors, counting the soldier societies that invariably staked separate villages. Bridger said that hostile Northern Cheyenne were also in the vicinity, camped along Rosebud Creek, and that the Crows had told him it took half a day to ride through the villages. All told, it was the largest combined Indian force Bridger had ever heard of, and there was talk of destroying the white soldiers’ two forts. For once “Old Gabe” looked concerned. His rheumatism was bothering him, and he paced along the compound’s battlements, “constantly scanning the opposite hills that commanded a good view of the fort as if he suspected Indians of having scouts behind every sage clump or fallen cottonwood.”

notes

1. The cinematic images of the standard-bearing cavalry troop riding out from a fort to fight Indians have misled generations of moviegoers. The usual population of these forts was largely mounted infantry with a few true cavalrymen for support, reconnaissance, escort duties, and mail delivery.

2. If in fact the raids were led by North, Brown’s detail had failed to kill him, as he was hanged three years later in Kansas.

As Brown’s detail charged from the corral, Carrington ordered his twelve-pound field howitzer fired. The shells burst among the Indians, driving them back into the hills and scattering the cattle. Within minutes Brown had recaptured the herd and was driving the cattle back toward the fort when they crossed paths with an Army freight train coming up the Bozeman Trail. It had just delivered ammunition to Reno Station and was carrying another 60,000 rounds for the Fort Phil Kearny garrison. Among the train’s passengers were two civilian surgeons contracted to the battalion as well as a replacement officer, Second Lieutenant George Washington Grummond. Grummond—dashingly handsome, with the posture of a telegraph pole, and sporting the luxuriant facial hair typical of the era—had fought with the Michigan volunteers during the Civil War and was traveling with his pregnant wife, Frances.

Grummond was an odd case. On the one hand, at thirty years old he was the kind of experienced fighter you wanted by your side in Indian country. On the other, he was frightening. A stormy tempered alcoholic who had worked on Great Lakes merchant ships since childhood, he had risen from sergeant to lieutenant colonel during the war for his aggressive, if reckless, tactics. His junior officers lived in fear of him and eventually petitioned the adjutant general to investigate several incidents in which, they claimed, his whiskey courage had imperiled the troops. He was subsequently court-martialed and found guilty of threatening to shoot a fellow officer while in a drunken rage. But the Union Army needed officers, and Grummond was soon back in the saddle, leading a company of Michigan volunteers through General Robert Granger’s Tennessee campaign. He was finally relieved of field command when he jumped the gun during a precisely coordinated offensive against General Joe Wheeler’s Confederate forces on the heights of Kennesaw Mountain. His actions not only allowed Wheeler’s army to escape a pincer-like trap but also imperiled his own company, which was surrounded and nearly wiped out. “Not even a semblance of company organization” was one of the many negative performance reviews filed in his military jacket.

His personal life was equally chaotic. At the war’s onset Grummond had left behind in Detroit his pregnant wife, Delia, and his five-year old son, George Jr. Three years later, while stationed in central Tennessee, he began courting a naive southern belle, Frances Courtney, the nineteen-year-old daughter of a slaveholding tobacco farmer. Grummond abandoned his Detroit family, which now included an infant daughter, and in September 1865 married Frances. The two Mrs. Grummonds remained unaware of each other’s existence for the rest of his life. Postwar Victorian America was unlikely to accept Grummond’s tangled marital situation, and frontier service was an inviting alternative. So he applied for, and accepted, a commission in Colonel Carrington’s command. That was how a pregnant and somewhat bewildered Frances Grummond came to be seated in a freight wagon pulling into an army outpost in the terrifying middle of nowhere.

When the Grummonds’ train neared the fort’s main gate it was forced to halt in order to make way for an ambulance wagon racing in from Piney Island. Frances Grummond—who moments earlier had been nearly overcome with relief at seeing the picket atop Pilot Knob waving a welcome flag, followed by the sight of the sturdy, walled stockade— now recoiled, sickened. It is said that terror is dry and horror is wet, and the bloodsoaked torso in the open bed of the ambulance was indeed dripping wet. It was also naked, and next to the body a severed head rolled back and forth with each bump in the road. The head had been scalped, and the victim’s back was cleft with a tomahawk gash so deep it exposed the man’s spinal column. Frances Grummond had no way of knowing that somewhere on the prairie, a warrior was adorning his tepee with the thick yellow mane of the photographer Ridgway Glover.

Some of the troopers had considered Glover’s fate only a matter of time. Glover had seemed to consider himself invulnerable, wandering alone through the mountains to record his tintype “views.” Lately he had been camping with the woodcutters on Piney Island, and the day before he had announced his intention to return to the fort despite the fact that it was a Sunday, when no wood trains were scheduled. Glover had no horse, and he mentioned to one soldier that he considered it a fine day for a six-mile walk with his portable darkroom. The woodcutters warned him that this was insanity; he did not even carry a gun. But despite all he had seen, he had convinced himself that his civilian status conferred on him an immunity that the Lakota or Cheyenne would recognize and respect.

The next morning, just prior to the Grummonds’ arrival, the regular wood train heading to the pinery discovered his body on the road two miles from the post. His head was found a few yards away. In addition to the tomahawk wound, he had been disemboweled, and a fire had been lit in the cavity of his belly. Looking at the bloody, mangled form positioned on its stomach, one officer claimed that the Indians had sent a message. Glover, he said, “had not died brave.”

Frances Grummond would later write, “My whole being seemed to be absorbed in the one desire, an agonized but unuttered cry, ‘Let me get within the gate!’ That strange feeling of apprehension never left me.” She spent a restless first night at Fort Phil Kearny, finally falling asleep sometime after midnight. When she and her husband awoke the next morning their tent was buried beneath a foot of snow.

In October 1866 the rift between Lakota moderates and militants widened. Indian agents were again putting out feelers regarding treaties, and with winter approaching and more gifts in mind, some Oglalas were inclined to listen. One of them was Old-Man-Afraid-Of-His-Horses.

Although technically still a Big Belly, he had lately reverted to subtle calls for diplomacy, and as a result the most hostile tribal factions were gravitating to Red Cloud, now recognized as the supreme Lakota war chief, the blota hunka ataya. It may have been tempting, at this moment, for Red Cloud to side with Old-Man-Afraid-Of-His-Horses. The banks of the prairie creeks were crusting over with ice, and Red Cloud was now fortyfive, and in earlier days he would have been free to rest on his reputation as a warrior who had proved himself again and again and enjoy life —to grow fat hunting deer, buffalo, and antelope; to sire more children; to instruct his children and their children in the old ways.

Instead, when the Little White Chief had sent his Bluecoats north to the Bighorn to build a second fort, it was Red Cloud who sponsored a formal war-pipe council among the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne. He proposed a major offensive against the original fort between the Piney creeks once the snows completely cut off communications among the whites. Red Cloud had attracted a large contingent of Miniconjou, Sans Arcs, and Brule fighters to his cause, and he had personally recruited warriors from formerly neutral Arapaho bands, citing the injustices to Left Hand at Sand Creek and the killing of Black Bear’s son the previous summer by General Connor’s “guns that shoot twice.” Further, in late August he swept aside a century of blood enmity to lead a delegation across the Bighorns to parley with the Crows. At the main Crow village he asked his hereditary enemies to join his war against the whites. As part of the bargain he offered to return to the tribe a portion of its old hunting grounds east of the mountains.

The bid was unsuccessful. Although several Crow braves were eager to don war paint against the whites, their Head Men remained noncommittal, promising only to reciprocate with a visit to the Bad Face camp. But the fact that Red Cloud dared to break long-standing tradition, and that some Crows had considered fighting alongside the Lakota, was evidence of the desperate High Plains Indians’ extraordinary existential crisis. One concession Red Cloud did receive from his longtime enemies was a series of one-day truces between the Lakota and the Crows that allowed each tribe to conduct trade fairs on the Bighorn. There, his braves were able to swap pelts, robes, and horses for Crow guns, mostly revolvers. Although the Northern Cheyenne possessed a few repeating rifles, Sioux and Arapaho warriors still made do with lances, war clubs, tomahawks, and arrows. A few Oglalas carried into battle single-shot muskets and percussion Hawken long rifles, but they were a distinct minority.

It was for this same reason, the need for firepower, that Red Cloud encouraged visits from the new generation of Laramie Loafers who had signed the white man’s treaty the previous spring. Though these Loafers, predominantly Brules, were forbidden to own more than one rifle (and were certainly unwilling to trade away their personal weapons), they were allowed to buy boxes of ammunition from white traders in exchange for the buffalo robes that Red Cloud supplied by the pack train. This was better than nothing. When the Loafers arrived in camp Red Cloud did not even bother to try to persuade them to fight with him. But taking the long view, he did pump them for information about the strength and movements of the soldiers along the Oregon Trail. He even swallowed his pride and sent emissaries to Sitting Bull’s Hunk papas far to the northeast, asking about the possibility of acquiring weapons from Canadian traders. Nothing much came of that.

Red Cloud had also begun to draw into his inner circle the maturing Crazy Horse, the leader of a cohort of young fighters who increasingly looked to the blota hunka ataya for guidance and direction. The gruff, physically imposing Big Belly and the slight, diffident warrior nineteen years his junior made an unlikely pair. It was common knowledge among the Lakota that Crazy Horse still pined for Black Buffalo Woman, whom Red Cloud had casually promised to another warrior. Still, there was no question that Crazy Horse and his Strong Hearts had been responsible for most of the destruction along the lower Bozeman Trail through the summer. The Strong Hearts had marauded as far south and east as Fort Laramie, and Crazy Horse had led the raiding party that sneaked into the Reno Station corral to run off the horses and mules one week before he ambushed the white soldiers at Crazy Woman Fork. As the weather turned and the emigrant trains thinned, the Strong Hearts had moved north to harass the woodcutting and hay-mowing details from Fort Phil Kearny, and when Crazy Horse intermittently returned from these forays there was always a seat awaiting him at Red Cloud’s council fire. Crazy Horse had never shown interest in mundane tribal politics—the elections of sub-chiefs, the planning of hunts, the debates over future campsites—but now that the talk centered on killing whites, he was often present, though he hardly ever spoke.

Meanwhile, as the last civilian trains of the season made haste for Montana before winter snows blocked the north country’s valleys and passes, two commissary caravans pulled into Fort Phil Kearny from Nebraska. Together they had hauled nearly 180,000 pounds of corn and over 20,000 pounds of oats, enough grain to carry the post’s weakened mounts through midwinter. Despite the feed delivery, however, when Colonel Carrington and Captain Brown inspected their remuda they determined that only forty horses were strong enough for the pursuit of the Indians.

The supply trains also carried a cache of much needed medical supplies; but, as with the horse feed, Carrington realized that these would not last until spring. The medicine consisted of the usual assortment of nineteenth-century remedies from the cure-all school of castor oil in the spring, mustard plaster in the fall. According to Army manifests the shipment also included tincture of peppermint oil, “for nausea and flatulence”; an ammonia liniment (obtained as a by-product from the distillation of tar, coal, and animal bones), for treating sore muscles; malt barley for digestive troubles; Epsom salts as a laxative; a fetid resinous herbal gum called asafetida, used to expel digestive gases; and ferrous iodide syrup to combat “consumption.” For the surgeons’ infirmary there were forty-five yards of adhesive plaster; 3,600 roller bandages; chlorinated soda and zinc sulfate for use as an antiseptic on arrow and gunshot wounds; and several cases of porter for, it was said, “restoring invalids.”

More good news arrived late that October with the return of the visiting general’s mounted infantry escort. There had been no news from Fort C. F. Smith since Bridger’s report, and the escort detail’s lead officer reported that the northern post, situated so close to friendly Crow country, had yet to be attacked. The escort had lost one scout killed and one trooper wounded riding through Sioux territory. In addition, three soldiers had deserted when the party skirted the Montana gold camps. Colonel Carrington took those desertions stoically. But desertion was not only a military problem; he also found himself dealing with civilians who had gone missing from Army freight trains. Teamsters signed round-trip government contracts in Omaha, counting on strength in numbers to get them up the Bozeman Trail with their hair intact. Once they reached Fort Phil Kearny, though, they might suddenly develop gold fever. Carrington dutifully listened to the contractors’ loud complaints before dispatching details to round up the wayward mule skinners. It was a waste of time, energy, and manpower. It was also part of his job.

Another issue was that the approaching High Plains winter appeared to be driving some people stir crazy. In mid-October a courier brought word from Omaha that the garrison commander whom Carrington had left in charge at Reno Station, a captain with whom Carrington had no more than a passing formal relationship, had arrested the lieutenant serving as his second in command. The young officer’s crime apparently consisted of allowing the Indians to make off with most of the post’s mules and horses during the August raid. Carrington was beside himself, not only because of what he considered unjust discipline, but even more because he had to learn of his own command’s turmoil from General Cooke. Fort Phil Kearny was still in too precarious a state for Carrington to journey the sixty-five miles to Reno Station to investigate the matter himself—he had sent an artillery battery with one of the mountain howitzers to camp on Piney Island, but the Indians were still picking off his men one by one. He was instead left to request that Cooke forward the indictment to him in the next mailbag.

Perhaps it was such humiliations, combined with the stress of frontier command, that contributed to the colonel’s own state of mind, which seems to have been bordering on paranoia. He began to fear that his junior officers were plotting against him, and he took to sleeping in his uniform and making his own nightly inspection rounds “to secure personal knowledge of deportment of guards and condition of post.” Moreover, the same courier who delivered news of the arrest at Reno Station carried another disturbing letter from Cooke. In it the general seemed to be assuming that a company of the 2nd Cavalry had recently arrived to reinforce Fort Phil Kearny—although in fact none had. Cooke “strongly recommended” that, since Carrington now possessed an abundance of mounts, he send his surplus horses to Fort Laramie to aid in its defense. A company of cavalry? Surplus horses? Was Cooke out of his mind? Between this order, the Reno Station incident, and Carrington’s own Queeg-like suspicions, it was as if some virulent strain of madness was infecting the U.S. Army’s officer corps.

And then the cowboys arrived.

Grubstake in hand, Story looked south to cattle country. Leaving his wife in the care of a local preacher’s family, he struck out for Texas. The Civil War had just ended, the North was clamoring for beef, and south Texas had an overabundance of both wild cattle and rancheros across the Mexican border virtually begging to be rustled. “Beeves” of both varieties eventually found their way to Fort Worth, the preeminent cow town on the Old Chisholm Trail. So did Story. He arrived in April 1866 with $10,000 sewn into the lining of his overcoat, purchased 1,000 longhorns, and hired a trail crew of twenty-seven cowboys. His destination was the busy railhead at Sedalia, Missouri.

On reaching the Kansas line, however, his drive was blocked by armed vigilantes who feared that their herds would contract Texas fever, a parasitic cattle disease that killed almost all other breeds coming into contact with the hardier longhorns. There were too many Kansans for even Story’s crew of rough cowpunchers to fight off, and he faced a decision—double back through the Indian Territory of present-day Oklahoma, or turn northwest along a route no cattlemen had ever before taken. Recalling his yearning for a good beefsteak in the stark, cold Montana mining camps, Story pushed the herd northwest. He had already covered over 300 miles and barely lost a cow. Virginia City was only another 1,000 miles away.

On their trek west Story and his cowboys lay over at Fort Leavenworth, where he stocked fifteen oxcarts not only with supplies for the drive but with crates of tools and bolts of calico to sell in gold country. The drovers then traced the Oregon Trail across Nebraska and into Wyoming until they reached Fort Laramie, where soldiers informed Story that Red Cloud had turned the Powder River Country into a bloody obstacle course. They would be fools to continue on, they were warned; the Lakota, Arapaho, and Cheyenne would raid them and stampede their herd. Moreover, the Fort Laramie garrison commander told Story that the colonel in charge of the Mountain District—another Ohio man, by the name of Carrington— had banned any civilian parties with fewer than forty armed men from overland travel. Story ignored him, purchased thirty new Remington breech-loading rifles and thousands of rounds of ammunition from the local sutler, and spurred his outfit up the Bozeman Trail.

Two days shy of Reno Station they were hit. A war party of Sioux boiled up over a frost-rimmed slope, stampeded the herd, and cut out several hundred cows. Two of the drovers suffered serious arrow wounds. That afternoon Story and his men rounded up the bulk of the cows and set a guard to protect them and the wounded men. He then led fifteen or so of his cowboys on a counterattack. The little posse of seasoned trackers followed the Lakota to a camp on the Powder River, where the stolen longhorns had been enclosed by a ring of tepees. They surprised the Indians with a night charge, the barrels of their Remingtons and Colts flaming as the startled braves panicked and fled. They recovered the animals, and one of Story’s hands later said that they wiped out the entire camp, although this seems unlikely. Actually, the cagey Story would never admit to any killing (although years later he did tell his son he had never killed an Indian before that night).

Leaving the two wounded cowboys at Reno Station, the party pulled into Fort Phil Kearny in mid-October. There, Colonel Carrington counted heads and said that Story did not have the requisite forty armed men to move north. Story argued that he and twenty-five cowboys armed with Remingtons equaled the firepower of at least 100 emigrants. The colonel stood firm and offered to purchase the beef at set Army prices. Both men understood that Story could command four or five times that amount from hungry Montana placermen. Story declined to sell. The colonel then ordered the Texans to graze their longhorns some distance from the post and wait to join the next civilian train bound for Virginia City. Story protested against the security arrangements; he did not like camping so far from the fort. Carrington coldly explained that he needed to conserve the prairie grasses on the nearby bottomlands for his own reduced Army herd. Story, perhaps admiringly, sensed a setup. He knew that this late in the season no other emigrant train was likely to roll up the Bozeman Trail, and he suspected that the fussy colonel really wanted to keep his stock in the area until winter iced them in and the Army could buy them cheap.

On the night of October 22 he called his trail crew together and put the matter to a vote—aye to leave, nay to stay. Only one man voted to remain; Story had him covered with his revolver almost before the word was out of his mouth. He hog-tied the dissenter, tossed him into a wagon, and the Texans hitched their oxen. The herd moved out in the dead of night. The next morning the naysayer was turned loose, given a horse and his gun, and told he could return to Fort Phil Kearny. He decided to keep riding for the brand.

Colonel Carrington was apoplectic when he discovered the cow camp vanished. His first instinct was to form a large pursuit detail—and it would have to be large, given the Texans’ firepower. But his legal training got the better of his temper and he instead spent the morning weighing his options. On the one hand he could dispatch a detail to overtake the drovers and force them to return. Story had disregarded a direct order issued by the commanding officer of the territory, the only law in the land. But would the headstrong trail boss obey? Or would the confrontation lead to a shootout between white men that could go either way and could also require an explanation before a military tribunal and lead to embarrassing newspaper headlines? On the other hand, his overriding mandate was the protection of civilians passing through the Powder River Country. In the end, whether from personal prudence or a sense of duty, Colonel Carrington dispatched fifteen mounted infantrymen to find Story and his herd and accompany them to Montana. It was a superficial gesture. The colonel knew as well as the cowboys that the soldiers and their single-shot rifles added little to the endeavor. But with their presence, technically, Story’s expedition satisfied Carrington’s forty-man decree.

The outfit—trailing by night, grazing by day— fought off two more attacks by Sioux raiders, and a cowboy was killed during a battle with Crows. But on a snow-muffled morning in early December the residents of Virginia City, Montana, awoke to find two dozen Texas cowboys flashing Mexican spurs and silver saddle pommels as they guided more than 900 longhorns down the muddy main street. It would be four more years before anyone else dared drive a herd from Texas that far north, and the expedition made Story rich. He became the north country’s first cattle baron, with his Paradise Valley herd growing to over 15,000 head, and soon afterward he was the Montana Territory’s first millionaire. He did not stop pistol-whipping claim jumpers or hanging alleged outlaws; and he also swindled government Indian agents, bribed federal grand juries, and even investigated the mysterious murder of his friend John Bozeman. But meanwhile, like most scoundrels of the Gilded Age, he smoothed his grifter edges by founding a legitimate bank, building a string of flour mills, endowing a hospital, and becoming the town of Bozeman’s largest real estate holder.

For all of his achievements, however, Story is best remembered for his epic cattle drive, which was one inspiration for the author Larry McMurtry’s Pulitzer Prize–winning saga Lonesome Dove. The fact that Story made it from Fort Worth to Montana is said to be no less remarkable than the fact that he tried in the first place. In any case, if Story’s exploits contributed in some small way to McMurtry’s characters Woodrow F. Call and Augustus “Gus” McCrae, that may be his true legacy.

That morning was unusually balmy, and the first order of business was a formal battalion inspection. A day earlier the troopers had been issued new uniforms from the quartermaster’s store to replace the patched, mended rags some had been wearing since the Civil War, and every man, weapon, and mount was lined up for review on the small plain between the stockade and the Big Piney. The soldiers in their smooth new blue blouses and trousers, burnished boots, and spit shined brass buttons met all the tests. But the remuda left something to be desired; and more than 100 of the old Springfield rifles were found to be “unserviceable, ” including twenty of twenty seven in one company alone.

Still, these problems did not dampen the festivities. Throughout the day the band played, poems were read aloud, Margaret Carrington was hostess at a tea social, cannons were fired, and a moment of silence was observed for those who had lost their lives. When a great luncheon on the parade ground was complete the chaplain stepped forward to offer a prayer and Colonel Carrington signaled to his flag bearers. It was time for the pièce de résistance.

For the past week a pair of enlisted men—one a former ship’s carpenter, the other an expert woodworker—had been putting the finishing touches on the garrison’s crowning achievement, a 124-foot flagpole. It was constructed of two lodgepole pine trunks, each as straight as a ruler, which had been shaved into octagons, painted black, and pinned together like a tall ship’s mast. Now the two enlisted men approached the pole and the regimental band played “Hail Columbia” as they unfurled an enormous American flag, twenty by thirty-six feet; gathered the halyards; and hoisted the Stars and Stripes, to a loud cheer. It was the first United States garrison flag to fly between the North Platte and the Yellowstone, and the vibrant red, white, and blue waving high above the prairie would serve as a beacon to travelers coming up the Bozeman Trail. After the official ceremonies, for the first time since their arrival at Fort Phil Kearny 110 days earlier, the 360 officers and enlisted men of the 2nd Battalion of the 18th U.S. Infantry Regiment were given permission to loaf the rest of the afternoon.

Two hours later they were recalled to their general quarters posts when Indians flashing mirror signals appeared on Lodge Trail Ridge. Among the Indians were Red Cloud and Crazy Horse.

next

Part V THE MASSACRE

By early autumn the 2nd Battalion of the 18th Infantry Regiment was stretched to its limit. The wood trains to and from Piney Island required constant security details, and continuous daylight lookouts were stationed on top of the Sullivant Hills and Pilot Knob. These were in addition to regular distress calls from emigrant trains under attack. Colonel Carrington was like a chess player forced to begin his match with only eight pieces. His rolls at the fort were down to just under 350 officers and men—a fact he was certain Red Cloud knew as well as he. A few Crow Head Men had offered to lend braves to the Army to help kill their hereditary enemies, but Carrington was leery of their true intentions. Despite the successes of the Pawnee scout corps, like most officers of the era he felt that relying on Plains Indians to fight other Plains Indians would reflect negatively on his own capability. Instead he finally petitioned General Cooke to allow him to reraise the company of Winnebago scouts the Army had recalled to Omaha earlier in the spring. Their dispersal, after all, had been a sop to Sioux sensibilities. That was now pointless.

While Carrington awaited Cooke’s reply he gladly hired on at Army base pay any civilians passing through the territory who asked for work. One such man was a Nebraskan, James Wheatley, traveling with his nineteen year-old wife, Elisabeth, and two young sons. Wheatley feared that the High Plains winter would close in on his family before they could reach the Montana gold fields and requested permission to open a civilian mess outside the post’s front gates. Carrington quickly agreed, and even supplied the lumber for the crude restaurant. Wheatley owned a seven-shot Spencer repeating rifle; he proved a crack shot and his wife a wonderful cook. Their wayfarers’ inn with its nightly dinners of fresh antelope, buffalo, and venison steaks became a kind of clubhouse for the civilian scouts, laborers, and teamsters, who remained after dinner to nibble cheese and crackers, drink whiskey, and trade “vile jokes and curses so gloriously profane that awed bystanders gazed upward, expecting the heavens to crack open.”

The Wheatleys’ clientele grew when a party of forty gold miners arrived one day from Virginia City. Their leader was a frontiersman with nearly two decades of experience in the West who told Colonel Carrington that the Montana lodes were playing out. He and his men had decided to explore richer prospects along the Bighorn. But they were harassed by hostiles throughout their journey south—only two days earlier two of their number had been killed in an ambush on the Tongue—and they now wished to winter over at Fort Phil Kearny while contemplating their next move. Carrington welcomed them with open arms. Forty rugged and well-armed men with their own horses constituted nearly the equivalent of a trained cavalry company, a rarity on the frontier. 1

The miners pitched a tent city just across Big Piney Creek and the next morning reported to the quartermaster, Captain Brown, for work assignments. They proved their worth almost immediately. Four days later, dawn’s first light streaking Pilot Knob to the east threw into relief a war party of 200 mounted Indians on the crest of Lodge Trail Ridge. The warriors bellowed, brandished their spears and war clubs, and charged down the slope toward the miners’ camp. An officer’s wife, watching from the post’s battlements, recorded the fight in her diary: “Hardly three minutes had elapsed after they came into view before the smoke and crack of the miners’ rifles, out from the cottonwood brush that lined the banks of the creek, had emptied half a dozen warriors’ [saddles] and brought down three times as many ponies.” Colonel Carrington was so excited he ordered the regimental band rushed to the parade ground to strike up a rousing battle hymn as soldiers cheered the fighting miners from the fort’s walls.

The engagement was one of two that season that the colonel recorded as “victories.” The other occurred about a week later when a breathless rider galloped into the stockade shouting that his wagon train was under attack not far down the trail. Carrington, following an instinct, had begun saddling and bridling the best horses at reveille each morning. The forethought now paid off. A relief detail led by Captain Brown and Lieutenant Bisbee was out of the quartermaster’s gate within moments, joined by half a dozen miners. The Indians dispersed at the sight of the rescue party but not before stampeding the train’s cattle. Brown and his men chased the Indians and longhorns for ten miles before overtaking them. Perhaps valuing the beef more than their lives, for once the Indians stood and fought. Brown’s party dismounted, formed a skirmish line, and withstood three mounted charges. Before the Indians withdrew, the soldiers and miners killed at least five of them and wounded sixteen more. The detail, with one trooper nicked by an arrow, also recovered all of the wagon train’s stock.

The small victory was noteworthy in another way. For months the prairie had rippled with rumors of white men, old mountain men, fighting alongside the Indians. The gnarled trappers, apparently as troubled as the Natives by “civilization” seeping through the Powder River Country and climbing their beloved Rockies, were even said to have planned and led attacks on the civilian trains. After this particular skirmish Captain Brown reported to Colonel Carrington that the Indian charges on his lines appeared to have been orchestrated by a white man. He was dressed in Lakota garb and was missing several fingers on his right hand, and he had ridden down on the soldiers screaming curses in English. In the final foray he was shot off his horse, but two braves scooped up his limp body. Carrington put this together with an earlier report about a “white Indian” with missing fingers—Captain Bob North —heading raids on emigrant trains. In his official dispatch to Omaha he reported the death of this Captain North.2

While the colonel reported these “significant blows, ” General Sherman was midway through his second tour of the frontier. The general’s mood had swung again, thanks to Red Cloud, and cold fury replaced the amiable disposition he had shown four months earlier in Nebraska. During a layover at Fort Laramie he parleyed with several of the Sioux sub-chiefs who had signed the previous spring’s treaty. When they admitted that they could not always restrain their rash young braves from joining raiding parties, Sherman’s famous temper flared, his red whiskers seeming to bristle. He had heard too much of this excuse. Turning to his interpreters but pointing dramatically toward the Indians, he said, “Tell the rascals so are mine; and if another white man is scalped in all this region, it will be impossible to hold mine in.”

Sherman then penned a letter to Colonel Carrington making his instructions clear. “We must try to distinguish friendly from hostile and kill the latter. But if you or other commanding officers strike a blow I will approve, for it seems impossible to tell the true from the false.” Carrington barely had to read between the lines. The second-highest-ranking officer in the United States Army had just declared open season on all High Plains Indians, friend or foe. Such was the temper of his own troops that the order was hardly necessary.

A few days later three Piney Island woodcutters were ambushed in a thick section of forest. Two of the enlisted men escaped to the island’s blockhouse with minor wounds. They told of watching their fallen comrade, Private Patrick Smith, shot through with arrows and scalped. Incredibly, Smith had not been killed, and he crawled half a mile back to the American lines leaving a trail of blood behind him. He was rushed by ambulance to the fort, where he died. That night at mess, graphic stories spread of Smith’s death. Scalped alive. Left for dead with the skin hanging in strips from his forehead. Arrows deliberately aimed to wound rather than to kill. It was unusually bad timing when nine Cheyenne, professing friendship, rode up to the fort near twilight and Colonel Carrington granted them permission to camp on the Little Piney. Someone started a rumor that they were the same Indians who had killed Pat Smith. It spread rapidly through the barracks, with the troopers expressing the same conviction as Sherman: It is impossible to tell the true from the false.

The American conspirators waited until midnight before some ninety men crept from their bunks and scaled the post’s walls. But the same chaplain who had made the heroic ride from Crazy Woman Fork got wind of the lynching party and woke Colonel Carrington. Carrington roused Captain Ten Eyck, who in turn gathered an armed guard. They arrived just in time to prevent the massacre. The mob tried to scatter, but two shots from Carrington’s Colt froze them. The colonel and Captain Ten Eyck recognized among the crowd some of their best fighting men. They took a moment to confer and concluded that they could not afford to make any examples. To take the Indians’ side and risk alienating the troops was too risky. The post’s tiny guardhouse already held twenty-four prisoners, most of them caught deserting. The battalion was in fact averaging a desertion every other day, and harsh discipline meted out here would only spur more “gold runners.” Carrington ordered the Cheyenne away, gathered the angry soldiers, and settled for a “brief tongue lashing” before marching them back to their quarters. It must have crossed Colonel Carrington’s mind that had the decision to stop the killings been Sherman’s, the general may not have been so quick to intervene.

The colonel was still contemplating this incident when Bridger returned from Fort C. F. Smith. He and Beckwourth had met with the Crows, who told them that Red Cloud was camped along the headwaters of the Tongue not seventy miles away with about 500 lodges of Lakota, Arapaho, and a few Gros Ventres. This meant anywhere from 500 to 1,000 warriors, counting the soldier societies that invariably staked separate villages. Bridger said that hostile Northern Cheyenne were also in the vicinity, camped along Rosebud Creek, and that the Crows had told him it took half a day to ride through the villages. All told, it was the largest combined Indian force Bridger had ever heard of, and there was talk of destroying the white soldiers’ two forts. For once “Old Gabe” looked concerned. His rheumatism was bothering him, and he paced along the compound’s battlements, “constantly scanning the opposite hills that commanded a good view of the fort as if he suspected Indians of having scouts behind every sage clump or fallen cottonwood.”

notes

1. The cinematic images of the standard-bearing cavalry troop riding out from a fort to fight Indians have misled generations of moviegoers. The usual population of these forts was largely mounted infantry with a few true cavalrymen for support, reconnaissance, escort duties, and mail delivery.

2. If in fact the raids were led by North, Brown’s detail had failed to kill him, as he was hanged three years later in Kansas.

30

FIRE IN

THE

BELLY

Moments past daybreak on

Monday, September 17, Red

Cloud struck again. A large

war party of Lakota and

Arapaho rode down into the

little valley east of the fort at

the juncture of Big Piney and

Little Piney Creeks. They

moved on what was left of

the battalion’s withered cattle

herd—only 50 cows remained

out of the 700 that had begun

the trip through Nebraska.

The pickets, no strangers by

now to surprise attacks, were

nonetheless confused to find

the Indians firing revolvers.

The raiders stampeded the

animals, but the post was

prepared. Brown and Bisbee,

alert to any action,

immediately mounted a

detail. Quartermaster Brown

was in charge of the fort’s

stock, and over the weeks the

job of chasing Indians had

naturally devolved to him. He

did it so often that the Indians

had come to recognize him

from his haircut—a friar’s

tonsure—and gave him the

nickname Bald Head Eagle.

Fortunately, Brown thrived

on the assignment—so much

so that, with Colonel

Carrington’s tacit approval,

he was stalling transfer orders

to Fort Laramie that he had

received a week earlier.As Brown’s detail charged from the corral, Carrington ordered his twelve-pound field howitzer fired. The shells burst among the Indians, driving them back into the hills and scattering the cattle. Within minutes Brown had recaptured the herd and was driving the cattle back toward the fort when they crossed paths with an Army freight train coming up the Bozeman Trail. It had just delivered ammunition to Reno Station and was carrying another 60,000 rounds for the Fort Phil Kearny garrison. Among the train’s passengers were two civilian surgeons contracted to the battalion as well as a replacement officer, Second Lieutenant George Washington Grummond. Grummond—dashingly handsome, with the posture of a telegraph pole, and sporting the luxuriant facial hair typical of the era—had fought with the Michigan volunteers during the Civil War and was traveling with his pregnant wife, Frances.

Grummond was an odd case. On the one hand, at thirty years old he was the kind of experienced fighter you wanted by your side in Indian country. On the other, he was frightening. A stormy tempered alcoholic who had worked on Great Lakes merchant ships since childhood, he had risen from sergeant to lieutenant colonel during the war for his aggressive, if reckless, tactics. His junior officers lived in fear of him and eventually petitioned the adjutant general to investigate several incidents in which, they claimed, his whiskey courage had imperiled the troops. He was subsequently court-martialed and found guilty of threatening to shoot a fellow officer while in a drunken rage. But the Union Army needed officers, and Grummond was soon back in the saddle, leading a company of Michigan volunteers through General Robert Granger’s Tennessee campaign. He was finally relieved of field command when he jumped the gun during a precisely coordinated offensive against General Joe Wheeler’s Confederate forces on the heights of Kennesaw Mountain. His actions not only allowed Wheeler’s army to escape a pincer-like trap but also imperiled his own company, which was surrounded and nearly wiped out. “Not even a semblance of company organization” was one of the many negative performance reviews filed in his military jacket.

His personal life was equally chaotic. At the war’s onset Grummond had left behind in Detroit his pregnant wife, Delia, and his five-year old son, George Jr. Three years later, while stationed in central Tennessee, he began courting a naive southern belle, Frances Courtney, the nineteen-year-old daughter of a slaveholding tobacco farmer. Grummond abandoned his Detroit family, which now included an infant daughter, and in September 1865 married Frances. The two Mrs. Grummonds remained unaware of each other’s existence for the rest of his life. Postwar Victorian America was unlikely to accept Grummond’s tangled marital situation, and frontier service was an inviting alternative. So he applied for, and accepted, a commission in Colonel Carrington’s command. That was how a pregnant and somewhat bewildered Frances Grummond came to be seated in a freight wagon pulling into an army outpost in the terrifying middle of nowhere.