The Heart of Everything That is,The Untold Story of Red Cloud,

An American Legend

By Bob Drury & Tom Clavin

21

BURN THE

BODIES

EAT THE

HORSES

Sitting Bull was angry. A

month earlier, about when

Red Cloud fell on Bridge

Station, Sitting Bull’s

Hunk papas had tried to pick a

fight with the garrison

stationed at Fort Rice in

North Dakota. The timing

was serendipitous. The

Indians had not planned the

simultaneous raids; it was

merely the season. But Sitting

Bull had even less success

than Red Cloud. Geography

was his downfall.

A year earlier, in the wake of his victory on the Upper Knife, General Sully had ordered his engineers to construct the fort on a steep plateau overlooking the west bank of the Missouri. The plain surrounding the outpost was sketched with low, sageen crusted bluffs broken only by dark ravines running to the horizon. As Sully had planned, the soldiers on the parapets could see for miles in every direction, and when Sitting Bull’s decoys appeared before their gates the lookouts had no trouble making out the main body of 400 to 500 Hunk papas and Dakotas trying to conceal themselves behind the distant buttes. The post commander formed a defensive skirmish line along the riverbank that furled around the stockade’s cottonwood walls, but refused to allow his men to go any farther. The Sioux made one frantic charge, loosing a storm of arrows and musket balls, but fell back under an American artillery bombardment. At this post, unlike Bridge Station, there was no wagon train in need of rescue. The soldiers held their position, and their howitzers kept the Sioux well out of arrow and musket range. Sitting Bull led a sullen retreat.

When a month later his outriders spied the billowing dust clouds of Colonel Cole’s force meandering not far from where the Powder empties into the Yellowstone, Sitting Bull and his frustrated Hunkpapas jumped them like angry badgers.

Cole’s force outnumbered the attackers by four to one, but his men and their horses were all debilitated after marching for weeks through the low, flat heat of a baking drought that left their skin cracked and their lips, tongues, and eyeballs coated with a thin pall of fine yellow loess soil. At the first sign of Indians, Cole ordered his troop to assume a defensive position, corralling up near a grove of leafy scrub oak. Through four days and nights the Sioux probed, running off a few horses and wagon mules, with Sitting Bull personally capturing one officer’s majestic black stallion. But the Indians could neither penetrate the makeshift battlements nor lure out its defenders.

It was weather that finally forced Cole’s hand. On the first day of September the temperature dropped seventy degrees and a freak blizzard swept down from the north, killing over 200 of the Americans’ weakened horses. After burning his extraneous wagons, harnesses, and saddles, Cole had no choice but to march his men up the Powder. Sitting Bull had sent out messengers to Red Cloud’s camp, and his Hunk papas and Dakotas were now reinforced by small parties of Oglalas as well as some Miniconjous and Sans Arcs. These Sioux kept up a steady harassment of the slow-moving Americans, albeit to little end. The farther southeast the troop drove, the more concerned Sitting Bull became over straying too far from his defenseless village back on the Little Missouri. His scouts informed him that General Sully had pulled back across the Missouri, but one never knew. The Hunk papas harassed the column for two more days, and then fell off to ride home. It was now Red Cloud’s turn.

On September 5, the Bad Face chief finally reacted to Colonel Cole’s intrusion by assembling 2,000 braves to meet the beleaguered American force. He chose as his battleground a bend in the Powder marked by tall, sheer sandstone bluffs broken by winding ravines. It was an ideal site for an ambush. No one knows why Red Cloud did not ride with the war party that day; some historians contend that after days of fasting and vision quests the Cheyenne chief Roman Nose begged for the honor of leading the combined Sioux-Cheyenne contingent. Red Cloud apparently did grant Roman Nose that honor, and in his own stead sent Crazy Horse and Young-Man-Afraid-Of His-Horses.

Without the Oglala Head Man present, however, the Indians reverted to their age old battle tactics. Instead of ambushing the troopers from the rocky ridges, or even surprising them head-on, warriors broke into small groups according to their soldier societies, intent on stealing horses and counting coup. Some had wonderful luck. A flight of Cheyenne led by Roman Nose chased a feckless company of cavalry into a spinney of cottonwoods banking the north side of the Powder. The Indians dismounted, and using the thick leafy spurge as cover, crept in after them. Near the riverbank they broke into a clearing, where they found eighty saddled mounts tied to the bushes. Across the river the cavalrymen were emerging, dripping wet. None had fired a shot.

Buoyed by this small victory, Roman Nose attempted to rally his attackers into a coherent battle group. But by this time the main body of Cole’s troops had once again formed its wagons into a hollow square, its rear against the high hills. As Roman Nose policed the Indians into a loose skirmish line between the Powder and the bluffs, Crazy Horse approached with a request. He wanted to draw out the Americans with a dare ride. This had been his signature tactic throughout the Crow wars of the late 1850s, a feat so stunningly brave that it would inspire his fellow fighters. Roman Nose of course knew all about Crazy Horse’s famous dare rides, and assented. Three times a nearly naked Crazy Horse galloped the length of Cole’s defensive lines, a slim, ghostly figure hunched low over his war pony’s lithe neck. His sudden, darting runs resembled the lightning quick swoops of his animal spirit, the red-tailed hawk. He taunted the soldiers to come and fight. None would, although bullets whistled past him and made tracks in the earth at his horse’s hooves. Crazy Horse finally quit—his horse for once unscathed.

Not to be outshone, Roman Nose spurred his white pony across the dusty no-man’s-land with its clumps of sedge and needle grass. His eagle war bonnet trailed the ground as he too raced from one end of the American position to the other, screaming insults and bellowing challenges. Again the soldiers stayed put. The Cheyenne managed three rushes before his horse was shot and killed. At this the combined tribal force charged the corral en masse. They were repelled by whistling grapeshot and the crackling reports of hundreds of Spencer carbines. As a smoky dusk fell over the battlefield the Indians predictably grew tired of the standoff. The Cheyenne were the first to depart, riding off to strike camp and move east toward the Black Hills in preparation for the fall buffalo hunt. Cole took advantage of this to set his column on the move. He drove southwest as a few Sioux continued to trail him, intent mainly on stealing horses. But the opportunity for a showdown had passed.

Three days later another arose when Cole’s Pawnee scouts, trailed by a platoon of cavalry, topped a ridgeline and nearly blundered into the eastern edge of Red Cloud’s huge camp on the Tongue. A band of twenty-seven Cheyenne, one of the last to depart for winter camp in the east, were the first to notice them. But the Pawnee scouts were so distant that the Cheyenne merely assumed they were either Lakota or Arapaho returning from the fight with the soldiers, and paid them no heed. The Pawnee scouts retreated and hid on top of a steep cut bank, allowing the now-moving Cheyenne to pass. Then they ambushed the Cheyenne and killed every one. When a messenger reported the situation to Cole, for once the colonel understood that he had the element of surprise. He took the offensive, organizing his troop into a European-style full frontal charge. Even the Kansas malcontents, sensing a do-or die moment, recovered their esprit de corps.

Red Cloud, meanwhile, was unprepared for the surprise attack. With his force depleted by the departure of the Cheyenne Dog Soldiers, he organized a frantic holding action. Women and girls raced to dismantle lodges as teenage herders rounded up ponies from the surrounding grasslands. The scene at the center of the Indian camp resembled a rodeo, with armed braves lassoing and mounting any horse available. It would not be enough. Cole had the strategic and tactical advantage. Then, suddenly, as if summoned by the Wakan Tanka itself, the weather again intervened. The sky to the west darkened nearly to black as a succession of billowing thunderheads growled down from the Bighorns. A driving sleet pounded the prairie for the next thirty-six hours, ending the fight and turning the loamy earth into a quagmire. The Indians slipped away in the dim light, and Cole lost another 400 horses and mules to the bitter cold.

When the storm broke on September 9 the dazed Americans again set to burning the last of their expendable supplies, including their wagons. Cole’s remaining animals were too weak and his men too exhausted to continue carrying the dead, and he ordered the corpses thrown onto the fires to spare them mutilation. He then led what remained of his ragtag troop southwest up the Powder River Valley. The high ridges on either side of the column teemed with hundreds of mounted Indians. But unlike Sitting Bull’s Hunk papas, or even the Southern Cheyenne —tribes whose years of warfare against the whites had resulted in the acquisition of some modern weapons— Red Cloud’s Oglalas and Brules for the most part relied on bows and arrows, useless at such a distance. One of Cole’s officers estimated that only one in a hundred Powder River warriors owned a good gun, and it was likely to be only a single-shot muzzleloader. Had even a quarter of Red Cloud’s braves possessed anything resembling the Army’s rapid-firing Spencers and Colts, Cole’s column would have been doomed. It was a lesson Red Cloud was to take to heart—bravery meant nothing in the face of repeating rifles and cannons.

For two days the Sioux flanked the line of troopers, most of whom were now on foot and weak with scurvy. They had passed nearly a month without hearing from General Connor, and appeared so pale and gaunt that daylight alone might kill them. The Lakota sensed their best opportunity to rub them out as they watched the exhausted, footsore soldiers begin to slaughter their dwindling supply of bony horses and mules and eat them raw. Unbeknownst to the Indians, the soldiers were also low on ammunition, and there was talk among them of forming a final corral and making a last stand. Such was their condition when Connor’s scouts, led by Jim Bridger, found their camp.

Bridger had proved something of a curiosity to Connor on the march north. The forty-five-year-old general was not quite as awed by the veteran scout as his younger officers were, and his skin was thin enough that he took it as a challenge to his rank and reputation when Bridger warned him before the expedition that the hangings at Fort Laramie “would lead to dreadful consequences later on the trails.” Now that Connor had ridden with Bridger for over a month, his negative perception of the old mountain man had hardened, and he found himself wondering if Bridger, who was sixty-one, had lost his frontier edge. The fissures and fault lines crosshatching his face could be read as a map of distress, and at times he seemed to have difficulty recalling the locations of river fords that could accommodate the column’s heavy freight wagons. Further, the general found Bridger’s disdain toward what he called “these damn paper-collar soldiers” far from endearing. And his guide’s failure—intentional or not—to inform him that the Indians he had clashed with on the Tongue were Arapaho, not Sioux or Cheyenne, sat like a burr under Connor’s saddle. Even so, no one was happier to gaze upon “Old Gabe’s” leathery visage that cold, dreary day in September 1865 than Colonel Cole and his starving troop.

Bridger told Cole that General Connor’s column was only sixty miles away. A short distance beyond Connor, he said, was a new fort stocked with abundant supplies. It was enough to give a jaunty step to Cole’s men, who reached the rectangular log structure in late September. Why Connor had stalled his march to build the small stockade—which he dubbed Camp Connor— virtually strangling his three pronged offensive in its cradle, he never made clear. His tussle with the Kansas mutineers may have affected his plans, as might the realization after the fight with the Arapaho that the hostiles were not the helpless savages he imagined. Moreover, while Cole’s men had been marching in circles in late August, Connor had raced to rescue a road grading team that had set out from Sioux City to expand John Bozeman’s trail. Eighty-two freight wagons had been pinned down for thirteen days by hundreds of Lakota led by Red Cloud himself at the Tongue River crossing near the Wyoming-Montana border. The Indians melted away at Connor’s approach. But despite the relief column’s apparent success the incident effectively ended any hope of opening a shorter route through the Upper Powder to the gold fields.

All told, the summer campaign had been a disaster. The United States Army spent the fighting season scouring the High Plains for hostiles and came away with nothing to show for it besides a record of bad judgment, poor discipline, and failure. The miscarried campaign to crush Red Cloud left General Connor too disgusted to even request written reports from his subordinates, and he worded his own dispatch as vaguely as possible. He minimized the number of Army casualties—between twenty and fifty—and inflated Indian losses to nearly absurd proportions, estimating between 200 and 500 killed or wounded. Meanwhile one of his own junior officers admitted, “I cannot say as we killed one.” Connor made no mention of the large herds of Army mules and big American horses now mingling with Indian ponies in winter camps, nor of the surly volunteers who finally staggered back into Fort Laramie in October—their uniforms so tattered that they reminded one officer of a line of “tramps.” And the general certainly did not dwell on helping to turn the neutral northern Arapaho into belligerents.

Dodge’s report to General Pope, on the other hand, described the expedition as a wild success. He wrote that with Camp Connor now garrisoned by a skeleton company, the United States had finally established a foothold in the heart of the Powder River Country. He described Connor’s fight with Black Bear’s Arapaho as a punishment to the Indians “seldom before equaled and never excelled.” He was forced to make one concession, suggesting that the Union Pacific’s proposed approach to the Rockies might be better laid nearer to the South Platte than to Red Cloud’s domain. Ironically, this was along roughly the same path Bridger had outlined for Captain Stansbury fifteen years earlier. Other than this, Dodge concluded, all that was needed to grind down the belligerent northern tribes once and for all and to open the Bozeman Trail was more time, funds, and matériel.

But Washington had lost its faith. One suspects that a scholarly member of Andrew Johnson’s staff reminded the president of King Pyrrhus ancient lamentation —“Another such victory and we are lost.” Dodge’s incessant requests for more troops and supplies was costing the government $24 million annually—$3.2 billion in today’s currency— and this money might better be spent on Reconstruction. The government saw no recourse but to fall back on a tried-and-true stratagem to deal with the prairie. The United States, Congress decided, would offer the High Plains Indians a new treaty. In this matter the politicians did not consult the generals, who had other ideas.

So wrote Colonel Henry Beebee Carrington on June 13, 1866, as he rode west at the head of the 2nd Battalion of the 18th U.S. Infantry Regiment. As he was still in eastern Nebraska, Colonel Carrington had yet to meet a hostile Indian, so he could not possibly have known how right he was. He was about to find out—and, for the moment, without his second in command, Captain William Judd Fetterman.

Following the end of the Civil War both Carrington and Fetterman had decided to make the Army their career. Though Carrington was only nine years older than Fetterman, they personified the fault line between the old school military and a new breed of soldier steeped in total war. Carrington, the well-schooled attorney fond of reading his Bible verses each morning in Greek and Hebrew, had spent the conflict overseeing the Union Army’s Midwestern recruiting efforts with enough efficiency to have been credited with bringing 200,000 volunteers into the service. He had also maintained prisoner-of-war camps, and he prosecuted the rebel Copperheads who fomented the “Great Northwest Conspiracy.”1 He never saw action, but these accomplishments were enough to earn him a temporary and largely ceremonial brevet promotion to brigadier general. Fetterman, on the other hand, had tactical and strategic battlefield expertise. He had also gained administrative experience in the latter stages of Sherman’s Georgia campaign, including service as acting assistant adjutant general to the 14th Corps, a position in which he was responsible for more than 10,000 men. His familiarity both with field conditions and with the military procedures and protocols of every type of command made him a more attractive candidate for the postwar officer corps. Both he and Carrington lost their volunteer brevet rankings and reapplied to the Regular Army’s 18th Infantry Regiment in Columbus, Ohio. Fetterman reverted to captain from colonel, and Carrington to colonel from general—a perceived slight that he felt for the rest of his life.

1. This was a bizarre attempt by a small group of rebels led by the Confederate spy Thomas Henry Hines to sneak into the United States via Canada, free southern prisoners of war near Chicago, and start an insurrection. Carrington returned to Columbus in part to mourn the death of his infant son— the fourth of his six children to die before the age of three. He also began to lobby for a choice assignment on what he saw as the Army’s next great national stage, the Frontier. At war’s end, the service had been bloated with thousands of brevet colonels and generals, and Carrington—a small, gaunt, tubercular administrator—did not seem to stand much of a chance. But he was determined to will his heroic interior fictions into reality, and he had many powerful friends. He began writing letters not only to old acquaintances from the days when, as a young man, he had served as Washington Irving’s secretary, but also to more recent connections such as Salmon Chase, by now chief justice of the United States. He also reached out to his former law partner William Dennison, who had been the governor of Ohio and was now the postmaster general. His contacts came through.

At the end of the war Fetterman also rode north to Columbus. His stay was shorter. Though his dossier bulged with honors and citations, he did not have Carrington’s political clout. In the fall of 1865 Fetterman was assigned to recruiting duties in Cleveland just as Carrington with his wife, Margaret, and their two sons —six-year-old Jimmy and the younger Harry—departed for the West with 220 men of the 2nd Battalion of the 18th. The troop was undermanned by almost 700 soldiers, and the party reached Fort Leavenworth in Kansas by railroad and riverboat in early November in the midst of one of the most brutal Plains winters on record. It was the Carrington family’s first time away from urban comforts, and the shock of roughing it was registered by Margaret Carrington, who noted in her journal that the mercury in her thermometer had apparently frozen at twelve degrees below zero (a physical impossibility) and “two feet of snow had to be shoveled aside before a tent could be pitched.”

While the Carringtons and the 18th acclimated to this new reality, a war-weary nation was recoiling at the notion of further conflict, particularly with Indians. And vocal religious organizations, such as the Quakers, turned their attention from emancipation to the justice and wisdom of America’s treatment of the western tribes. Every pulpit represented numerous voters, and eastern politicians took notice. Moreover, the preachers’ public campaigns provided humanitarian cover for the new peace policy of the “Radical Republicans” taking power in Washington. The real reason for a shift in Indian policy was, of course, budgetary. Politicians in both parties were pressured by taxpayers weary of supporting the professional, and expensive, Frontier Army when the costly task of Reconstruction was only beginning. Throwing more money into another Indian campaign while paying to clean up the detritus of the last was anathema. With the western volunteer militias melting away and the Army drawing down its total number of troops from more than one million to just under 60,000—most of whom were needed to police the South— any number of congressional investigative commissions were formed to study the “Indian problem.” The members of these committees tended to be both self-serving and naive, and grandstanding senators and congressmen began to personally conduct “fact-finding” missions to the West. Sand Creek was a favorite stopover for datelines and photo opportunities.

The easterners, however, were in for a surprise, for the westerners—whose population was still sparse— had no sympathy for the “savages.” Senator James Doolittle of Wisconsin, an ardent proponent of peace, was one example. In a speech at the Denver Opera House, he asked what he considered a rhetorical question: Should the Indians be placed on reservations and civilized, or exterminated? He did not receive the answer he expected, because the rest of his speech was drowned out as the audience shouted, “Exterminate them! Exterminate them!” Not long before, a similar audience at the opera house had greeted Colonel Chivington as a conquering hero. Despite such omens, Washington remained determined to reach some sort of compromise with the High Plains tribes— a clean, simple solution to avoid further bloodshed and expense. As another senator wrote to the secretary of the interior after meeting with western Indian agents, “It is time that the authorities at Washington realize the magnitude of these wars which some general gets up on his own hook, which may cost hundreds and thousands of lives, and millions upon millions of dollars.”

To that end, in the fall of 1865 Indian agents approached bands of Hunk papas, Yankton Ais, Blackfeet Sioux, Yanktons, Sans Arcs, Two Kettles, and Brules living near the Missouri River with a blunt message: the raids on emigrants and settlers must cease, and a war against the United States would be unwise. But America was not heartless, the agents added, and in exchange for acceptance of Washington’s latest peace offer they promised the Indians acreage, farm tools and seed, and protection against any tribes who took exception to these new agricultural pursuits.

The Sioux were naturally resistant. Living in houses, tilling fields, sending their children to school—these were white man’s values and principles. But the agents were aware that the Upper Missouri tribes had to this point suffered the most from the alarming thinning of the buffalo herds, and they reminded the Indians that the fifteen-year annuity payments from the Horse Creek Treaty were about to expire, and offered a solution—a new, twenty-year deal at increased rates. All they asked in return was that the bands move permanently away from the trails and roads leading west, and vow not to molest the whites defiling their old lands with mechanical reapers, threshing machines, and barbed wire. It was a stunning demonstration of the Indians’ desperation that by October enough pliable sub chiefs representing over 2,000 Sioux agreed to the treaty in a ceremony at Fort Sully, located at the mouth of the Cheyenne River.

The national conscience, troubled since Sand Creek, was assuaged, and newspaper headlines declared peace with the Sioux while eastern reporters and editors, unaware that “the Sioux” came in many variations, wrote that the Bozeman Trail was now safe for travel. The government was apparently equally delusional in its belief that a similar pact could be signed with Red Cloud and his followers. Indian agents sent runners into the Powder River Country to announce that come spring the United States was willing to offer even better terms in the form of exclusive rights to the game-laden territory lying between the Black Hills, the Bighorns, and the Yellowstone in exchange for the mere right of passage along the Bozeman Trail. There was no mention of farming. The message from Washington was clear: avoid war at all costs.

The politicians and Indian agents who promoted and fostered these peace offerings had many agendas, but most were spurred by one obvious and overriding fact—the Army was small and the Plains were enormous. The generals apparently disagreed.

A year before General

Grant[L] plucked him out of

obscurity, General Pope[R] had

published in the influential

Army and Navy Gazette an

indictment of what he

considered America’s

accommodationist policy

toward the High Plains tribes.

This approach to the “Indian

Problem” had the matter

backward, he wrote. Instead

of offering treaties and

bribing the Natives with gifts

and annuities, Pope

advocated placing the burden

of peace on the Indians. Were

he in command of national

Indian policy, he concluded,

he would give the tribes a

choice, take it or leave it: “an

explicit understanding with

the Indians that so long as

they keep the peace the

United States will also keep

it. But as soon as they commit

hostilities the military forces

will attack them, march

through their country, and establish military posts in it.

A year before General

Grant[L] plucked him out of

obscurity, General Pope[R] had

published in the influential

Army and Navy Gazette an

indictment of what he

considered America’s

accommodationist policy

toward the High Plains tribes.

This approach to the “Indian

Problem” had the matter

backward, he wrote. Instead

of offering treaties and

bribing the Natives with gifts

and annuities, Pope

advocated placing the burden

of peace on the Indians. Were

he in command of national

Indian policy, he concluded,

he would give the tribes a

choice, take it or leave it: “an

explicit understanding with

the Indians that so long as

they keep the peace the

United States will also keep

it. But as soon as they commit

hostilities the military forces

will attack them, march

through their country, and establish military posts in it.

Now Pope was in command of the Department of the Missouri. In March 1866 he issued General Order No. 33,[Take note of his hand above DC] which instituted yet another Army “District, ” the “Mountain District.” It included the route from the old Camp Connor (since renamed Fort Reno), northwest to Virginia City via the Bighorn and Yellowstone Rivers—in other words, the Bozeman Trail. The order also assigned Colonel Carrington’s 18th Infantry Regiment the task of reopening and protecting the route. In order to facilitate this assignment, Carrington would need to construct a string of forts through the heart of the Powder River Country, permanent structures replacing the mule driven supply lines that had failed so miserably in the past. For a striking illustration of the haphazard state of the postwar Army, one need look no further than the fact that on the very day General Pope issued Order No. 33, Generals Grant and Sherman decided to relieve him of command.

Grant had placed Sherman in charge of all western defenses, and he was also close to appointing a fifty six-year-old brigadier general, Philip St. George Cooke, to succeed Pope as head of the Department of the Missouri. Sherman suggested that the role called for a younger, more vigorous general, who might actually get out into the territory to experience personally the difficulties the troops and their officers faced on the frontier. He was afraid General Cooke would be content to lead from behind, in Omaha, and he was correct. But Grant was fond of Cooke, his old Virginia dragoon who had fought so admirably against Black Hawk, against the Mexicans, and against the Mormons. (Grant may have also wanted to reward Cooke for remaining loyal to the Union when his son, his nephew, and his famous son-in-law J. E. B. Stuart went over to the Confederacy.) Grant of course prevailed, and in March Cooke assumed command.

Amid this bureaucratic

confusion, Pope’s General

Order No. 33 stood. This

meant that by virtue of the

political and social contacts

that had secured him

command of the 18th Infantry

Regiment, the obscure

Colonel Henry Beebee

Carrington, with no fighting

experience and an attorney’s

approach to most military

hurdles, remained in charge

of the Army’s most ambitious

undertaking on the western

frontier—the defeat of Red

Cloud, the mightiest warrior

chief of the mightiest tribe on

the Plains. A plan to endow

such an officer with the

authority to build and

maintain outposts throughout

the very wilderness that had

been ceded time and again to

the Lakota by government

treaty appeared not only

duplicitous but idiotic. It is

not known if Colonel

Carrington had any idea that

he was to be used merely as a

placeholder, a competent fort

builder who was expected to

defend those outposts with

untested infantrymen until a

real fighter at the head of

well-trained troops could

complete the extermination of

the western tribes. As

Sherman wrote to Grant’s

chief of staff in the summer

of 1866,

“All I ask is

comparative quiet this year,

for by next year we can have

the new cavalry enlisted,

equipped, and mounted, ready

to go and visit these Indians

where they live.” Apparently,

he assumed that the Sioux

would wait.

Amid this bureaucratic

confusion, Pope’s General

Order No. 33 stood. This

meant that by virtue of the

political and social contacts

that had secured him

command of the 18th Infantry

Regiment, the obscure

Colonel Henry Beebee

Carrington, with no fighting

experience and an attorney’s

approach to most military

hurdles, remained in charge

of the Army’s most ambitious

undertaking on the western

frontier—the defeat of Red

Cloud, the mightiest warrior

chief of the mightiest tribe on

the Plains. A plan to endow

such an officer with the

authority to build and

maintain outposts throughout

the very wilderness that had

been ceded time and again to

the Lakota by government

treaty appeared not only

duplicitous but idiotic. It is

not known if Colonel

Carrington had any idea that

he was to be used merely as a

placeholder, a competent fort

builder who was expected to

defend those outposts with

untested infantrymen until a

real fighter at the head of

well-trained troops could

complete the extermination of

the western tribes. As

Sherman wrote to Grant’s

chief of staff in the summer

of 1866,

“All I ask is

comparative quiet this year,

for by next year we can have

the new cavalry enlisted,

equipped, and mounted, ready

to go and visit these Indians

where they live.” Apparently,

he assumed that the Sioux

would wait.

The officer who was to become Brown’s sidekick was the battalion adjutant Lieutenant William Bisbee, battle-scarred beyond his twenty-six years. Bisbee was a city boy from Woonsocket, Rhode Island, who had enlisted in the Army of the Republic at age twenty-two and was almost immediately commissioned as a lieutenant. He shared a tent and fought side by side with Fetterman from Corinth to Atlanta, and he was devoted to the captain. Like Carrington, Bisbee brought his family—his young wife and infant son— west with him, and at first the two clans became close. But their personal friendship did not last. Carrington was appalled when he observed Bisbee’s abusive behavior and language toward the enlisted men, and threatened several times to discipline him. Bisbee, who would rise through the ranks to general officer, never lost his contempt for his commander, and years later was to have his revenge.

Carrington’s junior officer corps also included Captains Henry Haymond and Tenedor Ten Eyck, both hard-bitten veterans. Haymond had commanded the 2nd Battalion of the 18th through some of its hardest fighting. The laconic Dutchman Ten Eyck, whose lazy right eye lent him the appearance of a professional gunfighter, was another soldier who liked his whiskey (he would later be cited repeatedly for public intoxication). He was one of the few college-educated officers on Carrington’s staff, and prior to the Civil War he had worked as a surveyor and lumberjack before catching gold fever. He was mining in Denver when the war broke out, and despite being over forty he returned to Wisconsin and enlisted as a private. Within six months he was commissioned as a captain in the 18th, and soon thereafter he was captured at Chickamauga. Tough enough to survive a bout of dysentery during the year he spent in a Confederate prison near Richmond, Ten Eyck was liberated in a prisoner exchange and returned to Wisconsin, where he had left his wife and five children when he joined the Carrington expedition.

Colonel Carrington’s staff officers, well acquainted with Army routine, understood the official reasons for his absence from the front during the war. That did not mean they had to respect those reasons, or even the punctilious man himself—an attitude that the colonel would only gradually come to understand. As it was, for now he was content to spend the winter of 1865–66 at Fort Kearney, a mere 194 miles west of Omaha, and it was from there that he wrote to General Cooke that he had acquired 200 “excellent” horses from Iowa and Nebraska cavalry volunteers mustering out of Civil War service as well as scores of freight wagons with which to haul sacks of seed potatoes and onion bulbs, surveying tools, and the construction equipment for his blacksmiths, wheelwrights, and carpenters. These included hay mowers, brick and shingle-making machines, window sashes, locks, and nails by the barrelful.

Despite this wealth of fine building materials, Carrington’s unit remained woefully short of modern weaponry. The officers and sergeants had been issued Colt revolvers, but the enlisted men still carried obsolete, muzzle-loading Springfield rifles remaindered from the Civil War. These guns were in such poor condition that many would not even fire. The War Department claimed that the single-shot Springfields cut down on ammunition wasted by soldiers carrying repeating rifles, but this was nonsense. It was an open secret in Washington that kickbacks to politicians by contractors from the Springfield armory kept the guns in circulation well past their effectiveness. Carrington undoubtedly was aware of this—he was, after all, an administrator at heart —but he certainly could not voice such a complaint in his dispatches. The best he could do was hint that his mission was compromised without more men and better guns, and until they arrived he decided to wait the situation out through the harsh Nebraska winter.

From Fort Kearney Carrington also issued his own General Order No. 1, requesting from Cooke’s warehouses “commissary and quartermaster supplies for one year . . . and fifty percent additional for wastage and contingencies.” In spite of his inherent cautiousness, Carrington was nothing if not optimistic, as indicated by his further submission for such delicacies as canned fruit and vegetables, sewing machines, rocking chairs, and butter churns that his wife, Margaret, believed would add “a domestic cast” to their impending journey. Heading into hostile Sioux territory, he was literally trading guns for butter.

It was at the Big Belly convocation that Red Cloud officially declared the 1865 fighting season over, and the Lakota agreed to reassemble for a war council in the spring. Perhaps they would even accept the white man’s invitation to come to Fort Laramie for treaty talks. After all, Red Cloud reasoned, what better way to size up an enemy than to meet him in person? Before the gathering disbanded, however, he and the six other Big Bellies chose four young men to act as ceremonial “Shirt Wearers” who would keep discipline among the wild braves and lead the war parties into battle. 1 Among these were Young-Man Afraid-Of-His-Horses and Crazy Horse. Red Cloud had begun to take a serious interest in Crazy Horse, the pale young warrior with the indefinable panache. He recognized in the young tribesman all the qualities required of a tactical field general. Even his name swaggered.

Now twenty-five, Crazy Horse had acquired the physical stature and mannerisms that would characterize him for life. He was slender and sinewy even for an Indian, and his lightness of carriage often left the impression than he was slighter than his five feet, nine inches. His ethereal quality was enhanced by his wavy hair, now waist length and usually plaited into two braids that framed his narrow face and his unusually delicate nose, which observers described variously as “straight and thin” and “sharp and aquiline.” Whites who met him over the years were usually struck most by his penetrating hazel eyes. One American newspaperman described them as “exceedingly restless,” and Susan Bordeaux Bettelyoun, the half-Brule daughter of the trader James Bordeaux, noted that Crazy Horse was a master of the sidelong glance. She wrote that he “hardly ever looked straight at a man, but didn’t miss much that was going on all the same.” In addition, Crazy Horse also exuded a natural melancholia, as if the humiliations and defeats he’d witnessed as a child—from Horse Creek to Harney’s massacre to the defeat of the Cheyenne on the Solomon River—had scarred his psyche. It was generally assumed that if Crazy Horse could indeed make magic, some of it was black.

Red Cloud may have felt that he needed such magic. Although either unwilling or unable to articulate it, much less understand the reasons for it, he and most of his cohort sensed a subtle change in the land of their youth. Droughts lasted longer, grasslands had become more sparse, and even the hardy wild mustang herds, like the buffalo droves, appeared to be thinning. In fact, the middle of the nineteenth century did mark the end of a 300-year neo-boreal cooling period known as the Little Ice Age, and this was about to have a greater impact on the American West than all the Indian wars combined.

Starting around 1550, falling temperatures in the northern hemisphere had produced snowstorms in Portugal, flooding in Timbuktu, and had destroyed centuries-old citrus groves in eastern China. Three centuries later, at the end of the Little Ice Age, Mary Mapes Dodge would be inspired to create a fictional character, Hans Brinker, whose silver skates carried him along frozen Dutch canals that would never again ice over. In North America the most severe repercussion from this meteorological anomaly was the desertification of buffalo ranges from the Canadian Plains to Texas. Yet the Powder River basin, because of its location between two mountain ranges and its many bountiful aquifers, escaped the environmental degradation affecting vast tracts of the West. Game proliferated in the area, cool breezes still wafted down from the mountains, and lush sweet grass scented the air. This alone made the country worth fighting for. But arguably it was not this alone for which Red Cloud fought: if he and his people had lived in the Mojave, or on a polar ice cap, and someone had tried to take it away, his reaction would have been the same. “If white men come into my country again, I will punish them again, ” he promised his tribesmen.

All of Red Cloud’s plans were of a single piece—to close down the pathway into his people’s verdant country, forever. He saw the world in primary colors, and if need be, he was willing to paint John Bozeman’s trail blood red.

Before their discovery, thousands of miners had trekked west toward the Montana gold camps via two primary routes. Both were considerably roundabout. The first followed a perilous stretch of the Missouri by way of Fort Benton in northcentral Montana that creased directly through Sitting Bull’s territory. The second passed by Fort Laramie on the Oregon Trail before climbing through the South Pass of the Rockies at the southern end of the Wind River range. There the more traveled route to the West Coast turned southwest toward Salt Lake, forcing the Montana-bound to make a hard trek north across a vast high-country desert dotted with alkaline puddles before doubling back across the Continental Divide over even higher peaks. Game was scarce in this country, but so were Indians, and this was the route for which Jim Bridger would advocate his entire life.

The wagon road blazed by John Bozeman, on the other hand, branched north off the Oregon Trail before even reaching the mountains, and ran up the east face of the Bighorns. It rolled around the north end of the range to follow the Yellowstone corridor upriver in a northwesterly direction to the Big Bend, where it swung due west and wound into Montana’s Beaverhead Valley. The 400 miles it cut from the previous routes saved one month to six weeks in travel time, and lush grasses, clean water, and fresh meat were plentiful.

In her classic book The Bloody Bozeman, Dorothy Johnson describes the naive, hopeful pilgrim who traversed the Bozeman Trail into the Montana wilderness. “He was a farmer eking out a living somewhere in the Middle West or fleeing the catastrophes of the War of the Rebellion. Or he was a lawyer or a doctor or a storekeeper, doing better than eking but wanting to do better still. He went west to find prosperity. This new man was not a born adventurer, but in his stubborn, sometimes cautious way he was a gambler. He gambled his life to better his condition, but he didn’t really believe that his hair might make fringes for a Sioux or Cheyenne war shirt or that his mutilated body might be clawed out of a shallow grave by wolves. He preferred not to face the fact that, if he should be captured, he might scream prayers for the mercy of death for hours before that mercy came.”

Ironically, were it not for the assistance of friendly Indians, Bozeman and Jacobs would probably have perished on their trailblazing journey. They almost died anyway, arriving at the Deer Creek station on the North Platte without mounts, half-naked, and nearly starved. But now that they knew the general conditions of the route, the two were confident enough to set up shop next to the Deer Creek telegraph station and sell their shortcut, offering their services as guides. The drawling, apple-cheeked Bozeman was a tireless promoter—if not exactly on a first-name basis with the bottom of the deck, he certainly put the confidence in “confidence man”—and outfitted himself in a fringed buckskin shirt and trousers to further impress prospective customers. He and Jacobs also hired a Mexican interpreter who was fluent in Sioux, and they soon attracted emigrants who were afraid of risking their wagons and stock over Bridger’s more arduous road. Bozeman assured the travelers that there were no hostile Indians along his route, and on July 6, 1863, he and Jacobs led the first train out of Deer Creek and into the wild Powder River Country.

This was the train that was intercepted by the Lakota and Cheyenne near the Bighorns and voted to turn back. Undeterred, the following summer Bozeman, this time without Jacobs, led a much larger and more heavily armed caravan from the North Platte to Virginia City without incident—the first emigrants to arrive in Montana along the new trail. A week before Bozeman departed from Deer Creek another train—124 wagons led by the wagon master Allen Hurlburt—had ventured out from the North Platte along the same route. But Hurlburt’s party had, proportionally, even more miners—418 men traveling with 10 women and 10 children—and Bozeman’s caravan passed it when Hurlburt stopped to prospect in the Bighorns. Bozeman was already being feted in Virginia City saloons when Hurlburt finally arrived. It is by virtue of this historical quirk that subsequent overland travelers to the Montana and Idaho gold camps did not roll along the “Hurlburt Trail.”

By 1866, however, word spread that traveling on the Bozeman Trail was too dangerous. This was the first year of the great post–Civil War migration west, and Bozeman’s outfit was nearly out of business. One Army trooper who was part of an expedition that fought its way up the route that summer wrote to the Army and Navy Journal, “We thought it an impossibility to get through. There will be no more travel on that road until the government takes care of the Indians. There is plenty of firewood, water, and game, but the Indians won’t let you use them.”

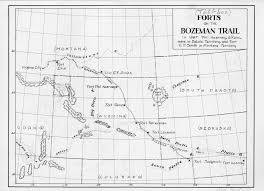

This more or less summed up Colonel Carrington’s orders—“Take care of the Indians.” He got off to a rocky start. In March 1866, while he was still wintering at Fort Kearney in Nebraska, Congress ordered the printing of an official Army survey delineating Bozeman’s route. The chart had been pieced together from Bozeman’s own rather opaque notes, geographic reports from General Connor’s expedition, aborted road-making expeditions (including the wagon train halted by Red Cloud and rescued by Connor a year earlier), and scattered newspaper clippings. When copies of this purported map reached Fort Kearney, Carrington and his officers were baffled. It resembled no chart they had ever seen, and was not much more than a squiggly dark line running vaguely northwest from the Oregon Trail through a vast, empty expanse bounded by the Black Hills to the east and the Bighorns to the west. There was no indication of elevation, nothing to differentiate desert flats from pasturage, and no mention of water holes or timbered country; and the few contoured watercourses that were outlined could have been either raging rivers or shallow streams. So spare were the map’s details that someone on Carrington’s staff actually dug up old copies of Lewis and Clark’s reports in hopes of matching descriptions of landmarks from their diaries.

Meanwhile, the battalion’s officers went about overseeing the mundane tasks common to nineteenth- century military expeditions striking out for the wilderness. The infantrymen repaired harnesses, greased axles, reshoed horses and mules, and cleaned weapons, including the unit’s one field howitzer and five snub-nosed mountain howitzers. They also learned to ride carrying their cumbersome Springfields. This by all accounts lent comic relief to an otherwise monotonous deployment, although Margaret Carrington noted that soon enough most of the men were able to saddle up, “and the majority actually made their first trip to water without being dismounted.” By mid-May, however, even this distraction was curtailed when a reinforcement battalion from the 18th consisting of 500 recruits arrived from Fort Leavenworth. Each unit—the one ensconced and the one arriving—assumed the other to be stocking rations, and Fort Kearney underwent a mild famine that left the men too weak to practice their horsemanship.

At least the food shortages were short-lived. By the spring of 1866 the Union Pacific had laid tracks as far as Fort Kearney, and a week after the arrival of the reinforcements a locomotive arrived hauling boxcars of commissary supplies. There were more recruits aboard as well, and riding along with them was General Sherman, making his first inspection trip to the frontier. (He had traveled as far as Omaha the previous fall.) Sherman, gaunt and hollow-cheeked, was apparently experiencing one of his manic stages. He charmed the officers’ wives, posing for photographs and suggesting to each that she keep a journal of what was certain to be an important chapter in American history. He oversaw bow-and-arrow competitions between the sons of the Pawnee scouts and the American boys, including Jimmy Carrington, who was awarded an Indian pony he named Calico after winning a long-distance shoot. But when Sherman met with Carrington and his officers he exhibited uncharacteristic passivity, suggesting that, “if possible, ” they avoid any contest of arms with the Natives.

If Sherman felt any apprehension over sending an officer who had spent the Civil War sitting behind a desk on such a “vital mission into the most contentious territory in his command, ” he kept it well hidden. Dinners were jovial and at least one makeshift cotillion was arranged, with the entertainment supplied by the 18th Regiment’s thirty-piece band. Carrington, who loved martial music, had insisted on bringing the musicians along, and they were his only troops outfitted with new, lighter Spencer carbines that fired .52-caliber bullets fed from a seven-round tube magazine. 2 After several days of relaxing under the pleasant June sunshine, Sherman bade the colonel godspeed and rode east, while Carrington marched the 18th west.

1. The actual quilled, fringed shirts presented to these braves were woven from bighorn fleece and decorated with hair, each lock representing a coup counted, scalp taken, or brave deed accomplished. Crazy Horse’s shirt had almost 250 locks.

2. Even posthumously Samuel Colt was changing the face of American warfare. His acolyte Christopher Spencer invented the manually operated, leveraction “Spencer” repeating rifle and carbine.

next

COLONEL CARRINGTON’S CIRCUS

A year earlier, in the wake of his victory on the Upper Knife, General Sully had ordered his engineers to construct the fort on a steep plateau overlooking the west bank of the Missouri. The plain surrounding the outpost was sketched with low, sageen crusted bluffs broken only by dark ravines running to the horizon. As Sully had planned, the soldiers on the parapets could see for miles in every direction, and when Sitting Bull’s decoys appeared before their gates the lookouts had no trouble making out the main body of 400 to 500 Hunk papas and Dakotas trying to conceal themselves behind the distant buttes. The post commander formed a defensive skirmish line along the riverbank that furled around the stockade’s cottonwood walls, but refused to allow his men to go any farther. The Sioux made one frantic charge, loosing a storm of arrows and musket balls, but fell back under an American artillery bombardment. At this post, unlike Bridge Station, there was no wagon train in need of rescue. The soldiers held their position, and their howitzers kept the Sioux well out of arrow and musket range. Sitting Bull led a sullen retreat.

When a month later his outriders spied the billowing dust clouds of Colonel Cole’s force meandering not far from where the Powder empties into the Yellowstone, Sitting Bull and his frustrated Hunkpapas jumped them like angry badgers.

Cole’s force outnumbered the attackers by four to one, but his men and their horses were all debilitated after marching for weeks through the low, flat heat of a baking drought that left their skin cracked and their lips, tongues, and eyeballs coated with a thin pall of fine yellow loess soil. At the first sign of Indians, Cole ordered his troop to assume a defensive position, corralling up near a grove of leafy scrub oak. Through four days and nights the Sioux probed, running off a few horses and wagon mules, with Sitting Bull personally capturing one officer’s majestic black stallion. But the Indians could neither penetrate the makeshift battlements nor lure out its defenders.

It was weather that finally forced Cole’s hand. On the first day of September the temperature dropped seventy degrees and a freak blizzard swept down from the north, killing over 200 of the Americans’ weakened horses. After burning his extraneous wagons, harnesses, and saddles, Cole had no choice but to march his men up the Powder. Sitting Bull had sent out messengers to Red Cloud’s camp, and his Hunk papas and Dakotas were now reinforced by small parties of Oglalas as well as some Miniconjous and Sans Arcs. These Sioux kept up a steady harassment of the slow-moving Americans, albeit to little end. The farther southeast the troop drove, the more concerned Sitting Bull became over straying too far from his defenseless village back on the Little Missouri. His scouts informed him that General Sully had pulled back across the Missouri, but one never knew. The Hunk papas harassed the column for two more days, and then fell off to ride home. It was now Red Cloud’s turn.

On September 5, the Bad Face chief finally reacted to Colonel Cole’s intrusion by assembling 2,000 braves to meet the beleaguered American force. He chose as his battleground a bend in the Powder marked by tall, sheer sandstone bluffs broken by winding ravines. It was an ideal site for an ambush. No one knows why Red Cloud did not ride with the war party that day; some historians contend that after days of fasting and vision quests the Cheyenne chief Roman Nose begged for the honor of leading the combined Sioux-Cheyenne contingent. Red Cloud apparently did grant Roman Nose that honor, and in his own stead sent Crazy Horse and Young-Man-Afraid-Of His-Horses.

Without the Oglala Head Man present, however, the Indians reverted to their age old battle tactics. Instead of ambushing the troopers from the rocky ridges, or even surprising them head-on, warriors broke into small groups according to their soldier societies, intent on stealing horses and counting coup. Some had wonderful luck. A flight of Cheyenne led by Roman Nose chased a feckless company of cavalry into a spinney of cottonwoods banking the north side of the Powder. The Indians dismounted, and using the thick leafy spurge as cover, crept in after them. Near the riverbank they broke into a clearing, where they found eighty saddled mounts tied to the bushes. Across the river the cavalrymen were emerging, dripping wet. None had fired a shot.

Buoyed by this small victory, Roman Nose attempted to rally his attackers into a coherent battle group. But by this time the main body of Cole’s troops had once again formed its wagons into a hollow square, its rear against the high hills. As Roman Nose policed the Indians into a loose skirmish line between the Powder and the bluffs, Crazy Horse approached with a request. He wanted to draw out the Americans with a dare ride. This had been his signature tactic throughout the Crow wars of the late 1850s, a feat so stunningly brave that it would inspire his fellow fighters. Roman Nose of course knew all about Crazy Horse’s famous dare rides, and assented. Three times a nearly naked Crazy Horse galloped the length of Cole’s defensive lines, a slim, ghostly figure hunched low over his war pony’s lithe neck. His sudden, darting runs resembled the lightning quick swoops of his animal spirit, the red-tailed hawk. He taunted the soldiers to come and fight. None would, although bullets whistled past him and made tracks in the earth at his horse’s hooves. Crazy Horse finally quit—his horse for once unscathed.

Not to be outshone, Roman Nose spurred his white pony across the dusty no-man’s-land with its clumps of sedge and needle grass. His eagle war bonnet trailed the ground as he too raced from one end of the American position to the other, screaming insults and bellowing challenges. Again the soldiers stayed put. The Cheyenne managed three rushes before his horse was shot and killed. At this the combined tribal force charged the corral en masse. They were repelled by whistling grapeshot and the crackling reports of hundreds of Spencer carbines. As a smoky dusk fell over the battlefield the Indians predictably grew tired of the standoff. The Cheyenne were the first to depart, riding off to strike camp and move east toward the Black Hills in preparation for the fall buffalo hunt. Cole took advantage of this to set his column on the move. He drove southwest as a few Sioux continued to trail him, intent mainly on stealing horses. But the opportunity for a showdown had passed.

Three days later another arose when Cole’s Pawnee scouts, trailed by a platoon of cavalry, topped a ridgeline and nearly blundered into the eastern edge of Red Cloud’s huge camp on the Tongue. A band of twenty-seven Cheyenne, one of the last to depart for winter camp in the east, were the first to notice them. But the Pawnee scouts were so distant that the Cheyenne merely assumed they were either Lakota or Arapaho returning from the fight with the soldiers, and paid them no heed. The Pawnee scouts retreated and hid on top of a steep cut bank, allowing the now-moving Cheyenne to pass. Then they ambushed the Cheyenne and killed every one. When a messenger reported the situation to Cole, for once the colonel understood that he had the element of surprise. He took the offensive, organizing his troop into a European-style full frontal charge. Even the Kansas malcontents, sensing a do-or die moment, recovered their esprit de corps.

Red Cloud, meanwhile, was unprepared for the surprise attack. With his force depleted by the departure of the Cheyenne Dog Soldiers, he organized a frantic holding action. Women and girls raced to dismantle lodges as teenage herders rounded up ponies from the surrounding grasslands. The scene at the center of the Indian camp resembled a rodeo, with armed braves lassoing and mounting any horse available. It would not be enough. Cole had the strategic and tactical advantage. Then, suddenly, as if summoned by the Wakan Tanka itself, the weather again intervened. The sky to the west darkened nearly to black as a succession of billowing thunderheads growled down from the Bighorns. A driving sleet pounded the prairie for the next thirty-six hours, ending the fight and turning the loamy earth into a quagmire. The Indians slipped away in the dim light, and Cole lost another 400 horses and mules to the bitter cold.

When the storm broke on September 9 the dazed Americans again set to burning the last of their expendable supplies, including their wagons. Cole’s remaining animals were too weak and his men too exhausted to continue carrying the dead, and he ordered the corpses thrown onto the fires to spare them mutilation. He then led what remained of his ragtag troop southwest up the Powder River Valley. The high ridges on either side of the column teemed with hundreds of mounted Indians. But unlike Sitting Bull’s Hunk papas, or even the Southern Cheyenne —tribes whose years of warfare against the whites had resulted in the acquisition of some modern weapons— Red Cloud’s Oglalas and Brules for the most part relied on bows and arrows, useless at such a distance. One of Cole’s officers estimated that only one in a hundred Powder River warriors owned a good gun, and it was likely to be only a single-shot muzzleloader. Had even a quarter of Red Cloud’s braves possessed anything resembling the Army’s rapid-firing Spencers and Colts, Cole’s column would have been doomed. It was a lesson Red Cloud was to take to heart—bravery meant nothing in the face of repeating rifles and cannons.

For two days the Sioux flanked the line of troopers, most of whom were now on foot and weak with scurvy. They had passed nearly a month without hearing from General Connor, and appeared so pale and gaunt that daylight alone might kill them. The Lakota sensed their best opportunity to rub them out as they watched the exhausted, footsore soldiers begin to slaughter their dwindling supply of bony horses and mules and eat them raw. Unbeknownst to the Indians, the soldiers were also low on ammunition, and there was talk among them of forming a final corral and making a last stand. Such was their condition when Connor’s scouts, led by Jim Bridger, found their camp.

Bridger had proved something of a curiosity to Connor on the march north. The forty-five-year-old general was not quite as awed by the veteran scout as his younger officers were, and his skin was thin enough that he took it as a challenge to his rank and reputation when Bridger warned him before the expedition that the hangings at Fort Laramie “would lead to dreadful consequences later on the trails.” Now that Connor had ridden with Bridger for over a month, his negative perception of the old mountain man had hardened, and he found himself wondering if Bridger, who was sixty-one, had lost his frontier edge. The fissures and fault lines crosshatching his face could be read as a map of distress, and at times he seemed to have difficulty recalling the locations of river fords that could accommodate the column’s heavy freight wagons. Further, the general found Bridger’s disdain toward what he called “these damn paper-collar soldiers” far from endearing. And his guide’s failure—intentional or not—to inform him that the Indians he had clashed with on the Tongue were Arapaho, not Sioux or Cheyenne, sat like a burr under Connor’s saddle. Even so, no one was happier to gaze upon “Old Gabe’s” leathery visage that cold, dreary day in September 1865 than Colonel Cole and his starving troop.

Bridger told Cole that General Connor’s column was only sixty miles away. A short distance beyond Connor, he said, was a new fort stocked with abundant supplies. It was enough to give a jaunty step to Cole’s men, who reached the rectangular log structure in late September. Why Connor had stalled his march to build the small stockade—which he dubbed Camp Connor— virtually strangling his three pronged offensive in its cradle, he never made clear. His tussle with the Kansas mutineers may have affected his plans, as might the realization after the fight with the Arapaho that the hostiles were not the helpless savages he imagined. Moreover, while Cole’s men had been marching in circles in late August, Connor had raced to rescue a road grading team that had set out from Sioux City to expand John Bozeman’s trail. Eighty-two freight wagons had been pinned down for thirteen days by hundreds of Lakota led by Red Cloud himself at the Tongue River crossing near the Wyoming-Montana border. The Indians melted away at Connor’s approach. But despite the relief column’s apparent success the incident effectively ended any hope of opening a shorter route through the Upper Powder to the gold fields.

All told, the summer campaign had been a disaster. The United States Army spent the fighting season scouring the High Plains for hostiles and came away with nothing to show for it besides a record of bad judgment, poor discipline, and failure. The miscarried campaign to crush Red Cloud left General Connor too disgusted to even request written reports from his subordinates, and he worded his own dispatch as vaguely as possible. He minimized the number of Army casualties—between twenty and fifty—and inflated Indian losses to nearly absurd proportions, estimating between 200 and 500 killed or wounded. Meanwhile one of his own junior officers admitted, “I cannot say as we killed one.” Connor made no mention of the large herds of Army mules and big American horses now mingling with Indian ponies in winter camps, nor of the surly volunteers who finally staggered back into Fort Laramie in October—their uniforms so tattered that they reminded one officer of a line of “tramps.” And the general certainly did not dwell on helping to turn the neutral northern Arapaho into belligerents.

Dodge’s report to General Pope, on the other hand, described the expedition as a wild success. He wrote that with Camp Connor now garrisoned by a skeleton company, the United States had finally established a foothold in the heart of the Powder River Country. He described Connor’s fight with Black Bear’s Arapaho as a punishment to the Indians “seldom before equaled and never excelled.” He was forced to make one concession, suggesting that the Union Pacific’s proposed approach to the Rockies might be better laid nearer to the South Platte than to Red Cloud’s domain. Ironically, this was along roughly the same path Bridger had outlined for Captain Stansbury fifteen years earlier. Other than this, Dodge concluded, all that was needed to grind down the belligerent northern tribes once and for all and to open the Bozeman Trail was more time, funds, and matériel.

But Washington had lost its faith. One suspects that a scholarly member of Andrew Johnson’s staff reminded the president of King Pyrrhus ancient lamentation —“Another such victory and we are lost.” Dodge’s incessant requests for more troops and supplies was costing the government $24 million annually—$3.2 billion in today’s currency— and this money might better be spent on Reconstruction. The government saw no recourse but to fall back on a tried-and-true stratagem to deal with the prairie. The United States, Congress decided, would offer the High Plains Indians a new treaty. In this matter the politicians did not consult the generals, who had other ideas.

Part IV

THE WAR

Memory is like riding a trail

at night with a lighted torch.

The torch casts its light only

so far, and beyond that is

darkness.

—Ancient Lakota saying

22

WAR IS

PEACE

The pending treaty between

the United States and the

Sioux Indians at Fort Laramie

renders it the duty of every

soldier to treat all Indians

with kindness. "Every Indian

who is wronged will visit his

vengeance upon any white

man he may meet.” So wrote Colonel Henry Beebee Carrington on June 13, 1866, as he rode west at the head of the 2nd Battalion of the 18th U.S. Infantry Regiment. As he was still in eastern Nebraska, Colonel Carrington had yet to meet a hostile Indian, so he could not possibly have known how right he was. He was about to find out—and, for the moment, without his second in command, Captain William Judd Fetterman.

Following the end of the Civil War both Carrington and Fetterman had decided to make the Army their career. Though Carrington was only nine years older than Fetterman, they personified the fault line between the old school military and a new breed of soldier steeped in total war. Carrington, the well-schooled attorney fond of reading his Bible verses each morning in Greek and Hebrew, had spent the conflict overseeing the Union Army’s Midwestern recruiting efforts with enough efficiency to have been credited with bringing 200,000 volunteers into the service. He had also maintained prisoner-of-war camps, and he prosecuted the rebel Copperheads who fomented the “Great Northwest Conspiracy.”1 He never saw action, but these accomplishments were enough to earn him a temporary and largely ceremonial brevet promotion to brigadier general. Fetterman, on the other hand, had tactical and strategic battlefield expertise. He had also gained administrative experience in the latter stages of Sherman’s Georgia campaign, including service as acting assistant adjutant general to the 14th Corps, a position in which he was responsible for more than 10,000 men. His familiarity both with field conditions and with the military procedures and protocols of every type of command made him a more attractive candidate for the postwar officer corps. Both he and Carrington lost their volunteer brevet rankings and reapplied to the Regular Army’s 18th Infantry Regiment in Columbus, Ohio. Fetterman reverted to captain from colonel, and Carrington to colonel from general—a perceived slight that he felt for the rest of his life.

1. This was a bizarre attempt by a small group of rebels led by the Confederate spy Thomas Henry Hines to sneak into the United States via Canada, free southern prisoners of war near Chicago, and start an insurrection. Carrington returned to Columbus in part to mourn the death of his infant son— the fourth of his six children to die before the age of three. He also began to lobby for a choice assignment on what he saw as the Army’s next great national stage, the Frontier. At war’s end, the service had been bloated with thousands of brevet colonels and generals, and Carrington—a small, gaunt, tubercular administrator—did not seem to stand much of a chance. But he was determined to will his heroic interior fictions into reality, and he had many powerful friends. He began writing letters not only to old acquaintances from the days when, as a young man, he had served as Washington Irving’s secretary, but also to more recent connections such as Salmon Chase, by now chief justice of the United States. He also reached out to his former law partner William Dennison, who had been the governor of Ohio and was now the postmaster general. His contacts came through.

At the end of the war Fetterman also rode north to Columbus. His stay was shorter. Though his dossier bulged with honors and citations, he did not have Carrington’s political clout. In the fall of 1865 Fetterman was assigned to recruiting duties in Cleveland just as Carrington with his wife, Margaret, and their two sons —six-year-old Jimmy and the younger Harry—departed for the West with 220 men of the 2nd Battalion of the 18th. The troop was undermanned by almost 700 soldiers, and the party reached Fort Leavenworth in Kansas by railroad and riverboat in early November in the midst of one of the most brutal Plains winters on record. It was the Carrington family’s first time away from urban comforts, and the shock of roughing it was registered by Margaret Carrington, who noted in her journal that the mercury in her thermometer had apparently frozen at twelve degrees below zero (a physical impossibility) and “two feet of snow had to be shoveled aside before a tent could be pitched.”

While the Carringtons and the 18th acclimated to this new reality, a war-weary nation was recoiling at the notion of further conflict, particularly with Indians. And vocal religious organizations, such as the Quakers, turned their attention from emancipation to the justice and wisdom of America’s treatment of the western tribes. Every pulpit represented numerous voters, and eastern politicians took notice. Moreover, the preachers’ public campaigns provided humanitarian cover for the new peace policy of the “Radical Republicans” taking power in Washington. The real reason for a shift in Indian policy was, of course, budgetary. Politicians in both parties were pressured by taxpayers weary of supporting the professional, and expensive, Frontier Army when the costly task of Reconstruction was only beginning. Throwing more money into another Indian campaign while paying to clean up the detritus of the last was anathema. With the western volunteer militias melting away and the Army drawing down its total number of troops from more than one million to just under 60,000—most of whom were needed to police the South— any number of congressional investigative commissions were formed to study the “Indian problem.” The members of these committees tended to be both self-serving and naive, and grandstanding senators and congressmen began to personally conduct “fact-finding” missions to the West. Sand Creek was a favorite stopover for datelines and photo opportunities.

The easterners, however, were in for a surprise, for the westerners—whose population was still sparse— had no sympathy for the “savages.” Senator James Doolittle of Wisconsin, an ardent proponent of peace, was one example. In a speech at the Denver Opera House, he asked what he considered a rhetorical question: Should the Indians be placed on reservations and civilized, or exterminated? He did not receive the answer he expected, because the rest of his speech was drowned out as the audience shouted, “Exterminate them! Exterminate them!” Not long before, a similar audience at the opera house had greeted Colonel Chivington as a conquering hero. Despite such omens, Washington remained determined to reach some sort of compromise with the High Plains tribes— a clean, simple solution to avoid further bloodshed and expense. As another senator wrote to the secretary of the interior after meeting with western Indian agents, “It is time that the authorities at Washington realize the magnitude of these wars which some general gets up on his own hook, which may cost hundreds and thousands of lives, and millions upon millions of dollars.”

To that end, in the fall of 1865 Indian agents approached bands of Hunk papas, Yankton Ais, Blackfeet Sioux, Yanktons, Sans Arcs, Two Kettles, and Brules living near the Missouri River with a blunt message: the raids on emigrants and settlers must cease, and a war against the United States would be unwise. But America was not heartless, the agents added, and in exchange for acceptance of Washington’s latest peace offer they promised the Indians acreage, farm tools and seed, and protection against any tribes who took exception to these new agricultural pursuits.

The Sioux were naturally resistant. Living in houses, tilling fields, sending their children to school—these were white man’s values and principles. But the agents were aware that the Upper Missouri tribes had to this point suffered the most from the alarming thinning of the buffalo herds, and they reminded the Indians that the fifteen-year annuity payments from the Horse Creek Treaty were about to expire, and offered a solution—a new, twenty-year deal at increased rates. All they asked in return was that the bands move permanently away from the trails and roads leading west, and vow not to molest the whites defiling their old lands with mechanical reapers, threshing machines, and barbed wire. It was a stunning demonstration of the Indians’ desperation that by October enough pliable sub chiefs representing over 2,000 Sioux agreed to the treaty in a ceremony at Fort Sully, located at the mouth of the Cheyenne River.

The national conscience, troubled since Sand Creek, was assuaged, and newspaper headlines declared peace with the Sioux while eastern reporters and editors, unaware that “the Sioux” came in many variations, wrote that the Bozeman Trail was now safe for travel. The government was apparently equally delusional in its belief that a similar pact could be signed with Red Cloud and his followers. Indian agents sent runners into the Powder River Country to announce that come spring the United States was willing to offer even better terms in the form of exclusive rights to the game-laden territory lying between the Black Hills, the Bighorns, and the Yellowstone in exchange for the mere right of passage along the Bozeman Trail. There was no mention of farming. The message from Washington was clear: avoid war at all costs.

The politicians and Indian agents who promoted and fostered these peace offerings had many agendas, but most were spurred by one obvious and overriding fact—the Army was small and the Plains were enormous. The generals apparently disagreed.

♔ ♟♔♟♔♟♔

The political struggle for

control of Indian affairs had

been raging, intermittently,

since 1849, two years before

the Horse Creek Treaty, when

tribal oversight was

transferred from the War

Department to the Office of

Indian Affairs. The Army

(correctly) considered the

politicians dishonest and

corrupt; the politicians

(equally correctly) deemed

the Army bloodthirsty and

shortsighted. One proof of the

latter belief had been General

Connor’s disastrous

campaign. By rights, the

bureaucrats pointed out, it

should have taught the

military some basic lessons,

the foremost being that for all

of America’s industrial

might, great winding columns

of Bluecoats blundering

across the prairie on futile

search-and-destroy missions

would play into the hands of

a mobile, cunning enemy who

knew every butte, hollow,

creek, and pasture. General

Sherman himself admitted

that finding hostile Indians

“was rather like looking for a

flea in a large clover field.”

Yet despite his new authority

as commanding general of the

Army, even Grant could not

alter the institutionalized

hubris and Indian-hating of

the War Department. By the

spring of 1866 the department

—as was said of the

Bourbons on their return to

power—had apparently

learned nothing and forgotten

nothing.Now Pope was in command of the Department of the Missouri. In March 1866 he issued General Order No. 33,[Take note of his hand above DC] which instituted yet another Army “District, ” the “Mountain District.” It included the route from the old Camp Connor (since renamed Fort Reno), northwest to Virginia City via the Bighorn and Yellowstone Rivers—in other words, the Bozeman Trail. The order also assigned Colonel Carrington’s 18th Infantry Regiment the task of reopening and protecting the route. In order to facilitate this assignment, Carrington would need to construct a string of forts through the heart of the Powder River Country, permanent structures replacing the mule driven supply lines that had failed so miserably in the past. For a striking illustration of the haphazard state of the postwar Army, one need look no further than the fact that on the very day General Pope issued Order No. 33, Generals Grant and Sherman decided to relieve him of command.

Grant had placed Sherman in charge of all western defenses, and he was also close to appointing a fifty six-year-old brigadier general, Philip St. George Cooke, to succeed Pope as head of the Department of the Missouri. Sherman suggested that the role called for a younger, more vigorous general, who might actually get out into the territory to experience personally the difficulties the troops and their officers faced on the frontier. He was afraid General Cooke would be content to lead from behind, in Omaha, and he was correct. But Grant was fond of Cooke, his old Virginia dragoon who had fought so admirably against Black Hawk, against the Mexicans, and against the Mormons. (Grant may have also wanted to reward Cooke for remaining loyal to the Union when his son, his nephew, and his famous son-in-law J. E. B. Stuart went over to the Confederacy.) Grant of course prevailed, and in March Cooke assumed command.

♞♟♟♔♟♟♞