CHEMICAL WARFARE

SECRETS ALMOST

FORGOTTEN

by

James S. Ketchum, MD

With a foreword

by

Alexander Shulgin, PhD

A Personal Story of

Medical Testing of Army Volunteers

with Incapacitating Chemical Agents

During the Cold War

(1955-1975)

FOREWORD

My first two interactions with the world of US Government

chemical warfare were in the 1950s or maybe the 1960s when I was

still a senior research chemist at the Dow Chemical Company in the

San Francisco Bay Area. They were totally opposite in the images of

secrecy and research process that they presented. I kept no notes, so

all is from ancient memory.

The first meeting was with two or three chemists in dark suits

and ties who were introduced to me and a half dozen other research

chemists as being government researchers in the area of potentially

interesting synthetic organic chemicals. We were not told from which

laboratory they came and the only clues to their areas of interest were

two synthetic reaction sequences which had been drawn on the

conference room blackboard. The man with the chalk told us that

these two pictures had been worked out successfully, and their

question was: could any of us propose a last step which might link

them together. The bottom compounds in the two schemes were

followed by arrows which pointed to an empty area at the bottom of

the blackboard. I asked them why not draw in the structure of the

desired product and they said that they were not at liberty to do so.

"Oh, nonsense," I said and got up and went to the blackboard

and drew the structure of the target. I drew the isomeric homologue

of tetrahydrocannabinol with the terpene double bond down in the

terpene 3,4-position and a 1,2-dimethylheptyl chain at the aromatic 3-

position. "This is the obvious product you want," I added as I

returned to my seat, "So why don't we discuss how this coupling

could be achieved."

There was an unmistakable discomfort shared by the

gentlemen from Washington. After a bit of discussion I volunteered

the statement, "Of course, with three chiral centers, there will be eight

distinct optical isomers possible, all of different pharmacology, and

some may not resemble marijuana at all in action." The meeting

broke up shortly thereafter. A lot of things just couldn't be talked

about.

The second meeting occurred at an informal conference with

some thirty people present, located at a retreat north of Los Angeles.

This was organized by my good friend (and secret trumpet player)

Daniel H. Efron, MD, PhD (1913-1972). This get-together was

sponsored by the Washington operation he ran, the Pharmacology

program at the National Institute of Mental Health. He told me to sit over there, pointing to an interesting looking man who was a total

stranger. We introduced ourselves. I said my name was Sasha

Shulgin, and he said his name was Van Sim. "Oh," I asked him,

"What is your first name?" "Van is my first name -- I am Van M.

Sim."

We quickly discovered that we were both fascinated by

psychedelics (they were called psychotomimetic drugs at that time)

and that we were both personally experimenting with them. My art

was the synthesis of new ones to compare the difference in activity

due to structural changes (this at my laboratory at Dow and in my

basement lab at home) and his curiosity was met by varying not the

compound so much as the setting and the immediate environment

around him (this at his laboratory at Edgewood Arsenal). Oh! A

government scientist with whom there was nothing in the world that

couldn't be talked about.

Thus, this foreword is intended to prepare the reader for a

story that has never before been told, the telling of the history, the

origins and the development of the physical structure and the variety

of people who worked at both the Edgewood Arsenal and its

precursor, the Army Chemical Center. This it indeed does, with a

flood of photographs and names and candid viewings of the people

who worked there during the 11 or so years that Jim Ketchum was a

major research person in the medical section. There is a mass of

small detail, ranging from unexpected visits and unusual interviews to

the conversations taking place during some of the drug experiments

with volunteer subjects. This is an intimate portrayal of the structure

of the research group, and the slow but inevitable changes in attitudes

and research goals that occurred over time.

But to me, this book is much more than an introduction to the

Edgewood Arsenal. It is an autobiography of the author himself, from

a young man with a developing medical career to an older, articulate

analyst of today's world of chemical weapons in general, but

particularly the instruments of psychochemical warfare.

It is a pleasure to be able to contribute to this story.

Alexander T. Shulgin, PhD

PROLOGUE

Hot Night in Halifa

It is 4 A.M. – close to the end of another hot night in the desert. American troops are

moving into position on the outskirts of the city, preparing to carry out an unprecedented tactical

plan. Actionable intelligence, validated by three sources, has established that several hundred

Islamic terrorists are in a particular part of the city, some no doubt asleep while others plan

attacks with IEDs (improvised explosive devices). A few may be preparing to strap on suicide

bombs. Most of the opposition consists of leftover loyalists; some are members of Al Qaeda and

a few are foreign extremists, drawn by religious fanaticism and eagerness to die for Islam.

During these dark early morning hours, some of the coalition soldiers are understandably

nervous. Their charge is to carry out a plan they have never attempted, except in simulated

exercises. Each platoon has gone through drills with gas masks for several days, sometimes also

wearing the hated, stifling suits that make it so difficult to function. Uncharacteristically, several

dozen vehicles, modified to serve as ambulances, have pulled up behind the ring of coalition

troops, tactically placed to make undetected exit from the city impossible. Further away, on

improvised pads, crews have modified more than a hundred helicopters and are examining them

once again to be sure they have done everything right. They chat and periodically glance at their

watches.

Inside each helicopter is a bank of unfamiliar munitions, brought in by armored, remotely

operated tanks. They are specially designed smoke generators, each loaded with 100 kilos of

sufentanil. According to what medics previously explained to the commanders, this synthetic

chemical is so potent that less than half a milligram can quickly produce profoundly

incapacitating central nervous system effects. This amount, one of them noted, is about same as

the quantity of LSD that they would need to cause a comparable degree of military

ineffectiveness. And the mode of action of this drug is quite different from LSD.

Once in the lungs, this tiny dose – less than a thousandth of the amount of powder in a

packet of artificial sweetener – less than the weight of a gnat’s wing – will rapidly bring sleep

and anesthesia lasting several hours. In larger doses, the drug will produce the same effects but

they will come on almost instantly and last longer. No one who inhales sufentanil can stay

awake, much less fight. And for added safety, it has been mixed with another synthetic chemical

that keeps it from stopping respiration.

The commander and his key subordinates meet in an improvised briefing room. The

colonel who is leading the operation reminds the small group that the participants must maintain

synchrony in their actions. He tells them again the importance of not using the radio except for

essential communications. Chitchat, although tempting, is prohibited.

Analysts have advised him that the delivery systems can take out almost every occupant in

the entire target area. The smoke generators are the latest in design. They worked extremely

well in all the tests, providing a smooth release and a uniform distribution. The colonel puts his

hand on the acetate-covered map, dragging tanned fingers across a crayon-shaded area where

most of the terrorists are concentrated.

The junior officers in the room have heard this before, but the final summation somehow

jolts them. This will actually happen. It may bring the solution to a big problem. Until now,

because they blend into the noncombatant civilian population, coalition troops could distinguish

the terrorists only by the rifles and rocket launchers they carry.

One young captain’s attention wanders shortly as he thinks of some of his Special Forces

personnel. Bitter memories of friends cut down by hooded snipers, cowards who fire from the

windows of ordinary homes, continue to haunt them. Even when they see them run inside a

building, the need to minimize “collateral casualties” forces the coalition units to hold their fire.

Their M-16 rifles and highly accurate shoulder-mounted missiles have to wait until the

“unfriendly” target is clearly isolated, lest they bring down a mother and child along with a

black-scarfed terrorist.

The meteorologists have reported that the weather is favorable, with a mild breeze, just

enough to carry the particles downwind without excessive drifting. If stronger, it would disperse

the smoke before it could settle to the ground. If weaker, its spread would be insufficient. By

good fortune, a mild inversion condition is present – it will push the air downward. The colonel

prays that the calculations are correct and that luck – a needed ingredient – will work in their

favor.

One of the junior officers asks whether the amount of material is enough to cover 100

hectares, roughly half of a square mile. He welcomes a firm reassurance. The terrorists could

protect themselves if they could mask in a few seconds, but at this early hour, with limited

equipment and training, this is a far-fetched possibility.

The colonel runs through the rest of the scenario. Once they locate target personnel,

lightweight plastic cuffs should be adequate to secure them. When they get the signal that the

area is clear, more than 200 medics will move in quickly. Leave the use of the antidote to the

aidmen. They have access to more than 100,000 syringes of naloxone (the standard antagonist

for morphine-like drugs). A single injector should be sufficient to revive several captives. Once

treated, most of the non-combatant civilians will be able to resume their usual activities. Since

symptoms may return when the naloxone wears off, medical surveillance of those affected must

continue for several hours.

The amount of panic is hard to predict. Some panic is inevitable, but the battalion medical

officer thinks it will be short-lived. Loss of consciousness will soon intervene. A sergeant

comments that there won’t be much shooting, an observation the colonel confirms with a grim

smile, noting that there will be few to shoot – unless the troops move in too quickly.

There will be injuries, mostly minor. One company commander speaks for the group –

they are tired of what they call “Boy Scout rules of engagement.” Like them, he believes the use

of their weapons should not require a first move by the enemy.

There is brief discussion of the “political correctness” that seems to govern everything. The

colonel points out that PC is a fact of life, even though the enemy will see it as weakness rather

than humane intentions. He reminds the men that it took much courage, both in the Pentagon and

higher up, to use an incapacitating agent in the face of almost certain disapproval by the world

community. Creative parsing of the Chemical Warfare Convention rules must underlie the

decision. This operation will make history, he says – and a mile-high pile of nasty headlines.

So, everyone must work together and do everything just right.

*****

Thirty minutes later helicopters are in the air and troops are once more testing their state-of the

art gas masks for leaks. When it is time to move in and round up the “bad guys” the soldiers

will have to wear their hated protective garments, as well. Each of these steam-bath suits has a

small strap-on kit, containing a dozen antidote injectors, along with the usual atropine syrettes for

nerve gas – there will be no shortage of medicine.

Smoke now drifts down and spreads, gradually creating a uniform fog. Sufentanil alone

might not be visible, but it is part of an aerosol made up of billions of very small drug impregnated

particles. Without additional material to piggyback them, even distribution of the

sufentanil molecules would be impossible. It’s a fine science. Only in a size range of one to five

microns – less than a tenth the diameter of a human nerve cell – will the particles reach the lower

lungs, and stay there.

*****

4:30 A.M. The smoke has begun to spread and permeate the partially open buildings. Loud

shouting is coming from the town. Men, as well as women and children are screaming and most

are running. They think they are about to meet the same fate as the Kurds did under Saddam.

Five minutes later, however, they are alive but still don’t know it. There is almost no noise on

the streets.

The troops advance slowly, prepared for snipers. Surprisingly, there are none. Dozens of

bodies are lying in the dirt. Armed Marines systematically enter buildings in accordance with

well-choreographed instructions. Inside, young and old lie motionless on the floor. Others seem

to be sleeping normally in rumpled beds. When the Marines find weapons, they place them and

the sprawled out men beside them on litters. Coalition soldiers carry the victims to nearby vans

and ambulances. Tape covers their mouths; non-slip plastic handcuffs hold their hands behind

them. Bigger trucks cart off the larger enemy weapons and munitions.

Now the medics are on the scene, busily injecting everyone – women and children first,

along with the elderly. They check them all to make sure they are breathing. Chests heave

slowly, barely perceptibly in some cases, but all seem to be getting enough oxygen. A few

victims are more critically affected. But, there is still time to arouse them with naloxone.

Sufentanil has a safety margin – enough to minimize the likelihood of respiratory arrest. No

guarantee against fatalities, but they will be far less than in a firefight. All those in critical

condition will get medical attention, whether enemy combatant or not.

*****

8 A.M. A hot sun heats the hazy air and illuminates the streets. The operation is essentially

over. More than four hundred suspected terrorists, grouped together in secure fenced enclosures,

are under heavy guard. No one is mistreated. Non -combatants, now fully awake but confused,

are being reassured by Arabic-speaking personnel. They will be okay – no serious aftereffects

and no prolonged restraint. But they will have to stay out of the affected area until it is washed

down with a neutralizing chemical, already being sprayed from specially equipped trucks.Sufentanil won’t penetrate the skin, but specks of it on material, clothing or other items, may lead

to ingestion – from fingers that later stray to lips.

Medical personnel tell the drowsy civilians to bathe and wash their clothes. They explain

that the sleep-producing chemical will soon be degraded by sun and natural chemical

interactions. Danger of secondary contamination will be minimal once the inactivation is

completed. Chemical clean-up teams will make sure of this, testing for residual drug before

allowing reoccupation of the area. Still dazed, the non-combatants seem to understand.

Meanwhile, taken by surprise, journalists are now busily gathering data, recording images

of both the treated and untreated, and barraging all the senior officers they can find with

questions. Already they are sending home live footage that will soon be showing up on TV sets

all over the world.

*****

Some readers will recoil from the fictional scene described above. It is a dramatic example

of “going-it-alone,” violating chemical warfare treaties, and bending or breaking international

laws. On the other hand, it illustrates the humane employment of what many still consider

inhumane weapons. Justification of the unorthodox attack will become clear when the inevitable

period of worldwide uproar subsides. Perhaps repugnance toward all chemical weapons will

now be more selective. Eventually, life-sparing drugs, by reducing the acknowledged brutality

of conventional warfare, may find acceptance.

The scenario is fantasy – some would call it science fiction. But, if it is possible, why

should it remain in the realm of the unthinkable? To understand the taboo that surrounds this

subject, one must examine how the history of warfare has shaped both national and international

policies. Such an examination is a major purpose of this book

1

COLD WAR: CHEMICAL

CALL TO ARMS

When I tell people that I’ve written a book about “my life in chemical

warfare,” they are generally polite but almost inevitably change the subject.

Perhaps it is not surprising, therefore, that no one has ever given a full account

of what we did at Edgewood Arsenal during the 1960s. It is unsettling, I

suppose, to hear a psychiatrist say he worked for a decade studying chemical

methods for “subduing” normal people. That is what I did, however, and this

book tells the story.

And it’s a story that needs telling, one that should have been told sooner.

So much of what exists in libraries and on the Internet is incorrect, and so many

accounts of what took place are distortions, that a mark of dishonor remains on

the escutcheon of our research at Edgewood Arsenal. I ought to know, because

I was there and fully immersed in that research.

Perhaps you have heard of BZ, for example, and believe it was a secret

concoction, far stronger than LSD, and able to drive people mad. You may not

realize that if you ever had major surgery, you probably received a drug just

like BZ before receiving anesthesia, to reduce unwanted secretions into your

lungs. You probably don’t know that more than a dozen similar drugs, all

related to BZ, were part of our experimental agenda.

Many think that the so-called Army volunteers we tested more than forty

years ago were not really volunteers. Some claim the subjects were required to

take drugs and then undergo interrogation to see if they would give up their

secrets. They believe that the chemicals we tested may have left lasting mental

or physical disabilities. In short, they assert that Army testing in the 1960s was

unethical, incompetent and carried out in violation of basic human rights.

These erroneous beliefs could have been dispelled by authentic information

long ago, but very little ever appeared in the public media.

So why now? As one of the few who are still alive and able to speak from

experience about the details of that decade of testing in the 1960s, I was jolted,

as were most citizens, by the events on 11 September 2001. Public fears and

misapprehensions about the possible extension of such recklessness to chemical

terrorism suddenly began to share the headlines. The real chemical story – the

story I had long wanted to tell in detail – suddenly seemed to be an important

one. I realized it was a remarkable story that few were still able to tell.

Fear of chemical attack has become an integral part of 21st century life.

Such an attack can come at any time and its consequences are difficult to

calculate. While weapons experts can provide descriptions of its effects, they

speak in terms of possibilities, not probabilities, because the magnitude of the

threat is uncertain and the likelihood of its occurrence unknowable.

Fear of chemical attack has become an integral part of 21st century life.

Such an attack can come at any time and its consequences are difficult to

calculate. While weapons experts can provide descriptions of its effects, they

speak in terms of possibilities, not probabilities, because the magnitude of the

threat is uncertain and the likelihood of its occurrence unknowable.

We wonder if a chemical attack will first be unleashed in a school or a

football stadium. Will most of the victims recover as in the sarin incident in

Japan? Or will thousands lie dead in the streets, as in the Kurdish villages of

Iraq? Will we be able to see the lethal cloud as it approaches or will it be

invisible? Will it sear our lungs, paralyze our muscles, eat into our flesh or

create terrifying hallucinations? Will death come quickly and painlessly or will

we linger in agony? How should we protect ourselves? What are the chances

of escape?

Unable to provide definitive answers to most of these questions, chemical

warfare specialists continued to repeat what we have already heard: that “a

single whiff” of a nerve gas such as sarin, or “a single drop” of a liquid nerve

agent such as VX can be fatal. They incorrectly warn us that an enemy can

pack enough such poison into a single missile warhead to annihilate thousands

of people, perhaps the population of an entire city. They note that even the skin

can be penetrated, but then tell us it is even more important to possess an

airtight mask.

No wonder the average citizen does not fully understand chemical warfare,

when even the best-informed experts do not provide us with straightforward

explanations. But perhaps they should not be too harshly criticized.

Descriptions of the mechanisms and sequence of nerve gas effects are complex.

Efforts to provide the details may produce confusion rather than enlightenment.

The deadliness of mortar shells and Kalashnikovs may be familiar, but the

complex effects of chemical weapons are not.

The reasons for this lack of clarity are, of course, not difficult to understand.

Chemical munitions must achieve their objectives amidst a multitude of variables.

Methods of delivery, devices used for dissemination, wind velocity, barometric

readings, air temperature, characteristics of the terrain and existing physical barriers

will all affect the outcome. In addition, one must take into account the possibility

of escape or evasion, as well as the potency and speed of action of the substance

itself.

And these considerations, although numerous, make up only a partial list of

factors influencing the outcome.

Ordinarily, a chemical attack would be expected to seek as many deaths as

possible. But there might be goals other than lethality. Kindling of panic and

demoralization may have a higher priority.

Paradoxical as it may seem, one can use chemical weapons to spare lives,

rather than extinguish them. The world watched in fascination when the

Russians, in November 2002, chose to deploy a relatively non-lethal chemical

weapon in a Moscow theater. Inside were a few dozen Chechen rebels, armed

with grenades and automatic weapons, holding hostage almost a thousand

innocent Russian civilians. The terrorists were prepared to destroy everyone in

the building if the Russians did not meet their demands. Fanatical and

desperate, they were not afraid to die along with their victims.

Russian military personnel and Chechen terrorists were locked in a stalemate

– a three-day standoff. Realizing that the stressed captives could not survive much

longer, a Russian commander made a novel, highly unorthodox decision. He

ordered a generator, loaded with a still unidentified substance – probably an

opiate related to, but far more potent than, morphine – and positioned it where

technicians could quietly pump it in as an aerosol from openings in the roof and

floor. Within minutes, it rendered the occupants unconscious. Half an hour

later, special troops stormed the building, killing the terrorists and freeing the

occupants.

Russian military personnel and Chechen terrorists were locked in a stalemate

– a three-day standoff. Realizing that the stressed captives could not survive much

longer, a Russian commander made a novel, highly unorthodox decision. He

ordered a generator, loaded with a still unidentified substance – probably an

opiate related to, but far more potent than, morphine – and positioned it where

technicians could quietly pump it in as an aerosol from openings in the roof and

floor. Within minutes, it rendered the occupants unconscious. Half an hour

later, special troops stormed the building, killing the terrorists and freeing the

occupants.

Regrettably, the operation was not entirely successful. Over a hundred hostages died along with the terrorists. Psychological shock and general debilitation, a result of insufficient food and water, no doubt substantially increased the number of mortalities. Lacking access to vital medications, some may have succumbed to unstable diabetes, heart conditions or renal disease. By injecting casualties as rapidly as possible with naloxone (the standard antidote for opioid poisoning) Russian medics saved the great majority. Had they started their rescue mission sooner, it is possible that many more would have survived.

However ambiguous the result, this dramatic incident stands out as an example of how a potent chemical agent can be used to preserve life, instead of as a “weapon of mass destruction.” Surprisingly, many observers deemed the operation morally indefensible. Still, in the opinion of others, it was a brilliant accomplishment under difficult circumstances.

The procedures followed in this crisis were remarkably similar to scenarios designed forty years earlier by our own Army doctors. Many of the readers of this book were very young, or not yet born, during that tense, uncertain time in history. After the defeat of the Axis powers in 1945, the Cold War, as Churchill named it, was rooted in the growing mutual distrust between America and the Soviet Union.[But gets get real and recognize that a lot of the cold war was psychological operations directed at the civilian population DC]

Although it was not a shooting war, the stakes were every bit as high as in the World War that had only recently ended. Most ominously, each nation had the ability to launch megaton nuclear missiles sufficient in number to annihilate the other. The resulting radioactive fallout would then continue to spread, wiping out populations in almost every corner of the earth. Popular novels and films trafficked in visions of “Armageddon” and “apocalypse”. The phrase “mutual assured destruction” became linguistic currency among journalists and commentators.

Regrettably, the operation was not entirely successful. Over a hundred hostages died along with the terrorists. Psychological shock and general debilitation, a result of insufficient food and water, no doubt substantially increased the number of mortalities. Lacking access to vital medications, some may have succumbed to unstable diabetes, heart conditions or renal disease. By injecting casualties as rapidly as possible with naloxone (the standard antidote for opioid poisoning) Russian medics saved the great majority. Had they started their rescue mission sooner, it is possible that many more would have survived.

However ambiguous the result, this dramatic incident stands out as an example of how a potent chemical agent can be used to preserve life, instead of as a “weapon of mass destruction.” Surprisingly, many observers deemed the operation morally indefensible. Still, in the opinion of others, it was a brilliant accomplishment under difficult circumstances.

The procedures followed in this crisis were remarkably similar to scenarios designed forty years earlier by our own Army doctors. Many of the readers of this book were very young, or not yet born, during that tense, uncertain time in history. After the defeat of the Axis powers in 1945, the Cold War, as Churchill named it, was rooted in the growing mutual distrust between America and the Soviet Union.[But gets get real and recognize that a lot of the cold war was psychological operations directed at the civilian population DC]

Although it was not a shooting war, the stakes were every bit as high as in the World War that had only recently ended. Most ominously, each nation had the ability to launch megaton nuclear missiles sufficient in number to annihilate the other. The resulting radioactive fallout would then continue to spread, wiping out populations in almost every corner of the earth. Popular novels and films trafficked in visions of “Armageddon” and “apocalypse”. The phrase “mutual assured destruction” became linguistic currency among journalists and commentators.

Some terrified citizens in the 1950s and 1960s became newsworthy subjects

for journalists and photographers, when they built and equipped their own bomb

shelters, filling them with essentials required for lengthy periods of underground

survival. The most nervous and wealthy property owners sometimes paid contractors huge sums to build structures deep below the surface, cynically

designing them to serve comfortably as luxurious apartments.

Nowadays, average citizens are somewhat less obsessed with the nuclear threat. Most world leaders likewise seem less preoccupied with the idea that radioactive weapons of mass destruction still pose an imminent danger, although countries such as Iran and North Korea continue to evoke considerable anxiety. Indeed, some unstable nations have stolen or bought the secrets of nuclear bomb making and even brag about their atomic capabilities, hinting darkly that, if provoked, they would not hesitate to use them.

It is interesting to note that even the acronyms for the weapons of mass destruction have changed. We used to be concerned about “NBC” – nuclear, biological and chemical weapons, respectively. Now it is “CBR” – chemical, biological and radiological – devices that provoke the greatest apprehension as we ponder how to plan our defenses. The promotion of “chemical” to the top and the demotion of “nuclear” to the bottom of the list reflect a growing belief – faith may be a more accurate term – that nuclear war is neither highly probable nor easily preventable. A certain degree of fatalism has crept into our national mentality. Many have decided to regard the possibility of nuclear war as too remote to warrant contemplation. The consequences would be too devastating, too unthinkable. If it occurs, it will almost inevitably bring on the final events of our life on earth – hardly worth discussing.

On the other hand, chemical weapons are not particularly difficult to manufacture and armies have actually used them in modern times. Thus, they are now vociferously touted as the most likely threats. Hastily developed detection measures have been deployed in an effort to locate and destroy deadly chemicals before terrorist groups can make use of them. Specially trained dogs now sniff for them in luggage and clothing. An expanding cohort of sophisticated inspectors is learning to hunt for them meticulously, despite mounting costs and annoying inconveniences to travelers. Scientists and engineers are hard at work developing more advanced imaging and analytic equipment capable of visualizing suspicious objects and materials, even when they are concealed within large vehicles and containers.

Modern fear of deadly chemical weapons is engendered by the hideous images of World War I, when countless thousands of courageous troops died helplessly in their trenches, fumes of chlorine, mustard and phosgene sweeping without mercy across their battlements. They clearly knew the nationality of their attackers and could have retaliated in kind, were it not for a woeful lack of comparable weapons. Today, however, the enemy does not align itself with a single nation and no one government can be held responsible for its attacks.

Twentieth century covenants against the use of chemical weapons, such as the Geneva Protocols, now restrain virtually all developed nations. Provisions of the more recent Chemical Warfare Convention (CWC) have further tightened the constraints, outlawing the use of every conceivable chemical weapon. The CWC even bans the use of agents as benign as tear gas (although, ironically, individual nations are not denied the option of using them against dangerous criminals within their own boundaries). And while the CWC prohibitions even extend to drugs and chemicals designed to incapacitate rather than kill, the United States has agreed to abide by them, abandoning the rational argument that prohibition of relatively safe weapons invites more dependence on those that cause more death and suffering.

President Dwight Eisenhower quickly gave his blessing to this effort. Later, newly elected President Kennedy, almost from the start of his administration, promoted a “Blue Sky” strategy that included incapacitating agents in the growing list of novel military options. Although, as coming chapters will reveal in detail, subsequent efforts to find and deploy humane chemical weapons were not totally successful, this hopeful objective guided secret research for more than a dozen years. Ultimately, even as hope dwindled, the experimental findings remained locked in tight secrecy for at least another decade.

The Edgewood laboratories eventually filed the wealth of data accumulated during these unorthodox studies, leaving them to languish in closely guarded cabinets. Later they moved these documents to even less accessible archives, determined to keep sensitive, classified reports out of the public limelight. Over time, waning interest and fading memories eroded many details of what we had learned, leaving only sketchy summaries and a significant gap in the historical record. This book goes back four decades in an effort to fill that gap.

Soon after General Creasy’s visionary project began to take shape, I

was assigned to Edgewood Arsenal to play a part in its development.

Strict secrecy would surround most of our work, lest the Soviets purloin

and make use of our diligently acquired information. Stern, sometimes

unreasonable rules prevented more than scant reference to our activities

from appearing in the media. Because most of the world’s anxiety focused

on the threat of nuclear war, “talking heads” gave relatively little attention

to the arcane medical experiments being conducted at our small chemical

installation.

Soon after General Creasy’s visionary project began to take shape, I

was assigned to Edgewood Arsenal to play a part in its development.

Strict secrecy would surround most of our work, lest the Soviets purloin

and make use of our diligently acquired information. Stern, sometimes

unreasonable rules prevented more than scant reference to our activities

from appearing in the media. Because most of the world’s anxiety focused

on the threat of nuclear war, “talking heads” gave relatively little attention

to the arcane medical experiments being conducted at our small chemical

installation.

By the time news writers began to report the story in more detail, the program had already begun to wind down. After 1970, the search for a militarily acceptable incapacitating agent had become increasingly out of fashion.

The years passed and the activities that took place in the Edgewood Arsenal medical laboratories during that decade were soon only vaguely remembered by a few of the former researchers. Civilian commentators sometimes spoke of the Edgewood program as a rather unethical, ill advised and generally sub-standard scientific effort that had yielded little of interest to the field of medicine. The erroneous belief that the program was primarily the brainchild of the CIA, already notorious for its ill-conceived attempts in the early 1950s to gain control of human behavior with drugs, added to these unflattering characterizations. Most participating physicians failed to rise to the defense and refused to grant interviews to investigative reporters, or shifted responsibility to their attorneys. Drawn by the scent of malfeasance, popular authors began to write books incriminating both the CIA and the Edgewood doctors.

The Edgewood Arsenal program and the earlier shady CIA experiments, involving surreptitiously administered LSD and related drugs, became indelibly linked in the public imagination.

Regrettably, no one other than those who had done the research seemed to

have much solid information about the details of our activities at Edgewood.

By default, fantasy and rumor took the place of verifiable facts. I watched with

distaste as invidious characterizations of our program appeared repeatedly in

paperback books and ultimately on oft-visited websites. In 1979, even the

prestigious journal Science published incorrect information about BZ, the very

potent atropine-like incapacitating agent most often mentioned in books and on

Internet websites. It was hard to blame the journal’s editor. Few who had been

at Edgewood wanted to talk about it, and most of the published information

was shamefully superficial.

Regrettably, no one other than those who had done the research seemed to

have much solid information about the details of our activities at Edgewood.

By default, fantasy and rumor took the place of verifiable facts. I watched with

distaste as invidious characterizations of our program appeared repeatedly in

paperback books and ultimately on oft-visited websites. In 1979, even the

prestigious journal Science published incorrect information about BZ, the very

potent atropine-like incapacitating agent most often mentioned in books and on

Internet websites. It was hard to blame the journal’s editor. Few who had been

at Edgewood wanted to talk about it, and most of the published information

was shamefully superficial.

By the time the original detailed technical reports were declassified (usually at least 12 years after they had first been distributed as restricted documents), most of those who had done the work had quietly moved on. Memories were vague, original data largely inaccessible, and motivation to publish them virtually non-existent. As the first Regular Army psychiatrist ever assigned to Edgewood Arsenal, I was only one of a small but growing number Army physicians actively involved in the drug testing.

For ten years, I was given the opportunity to play a leadership role in the search for a safe and effective incapacitating agent. The research design was embryonic in 1961, but slowly evolved into a highly structured method for evaluating candidate agents in Army volunteers. I was engaged in measuring the clinical effects of more than a dozen compounds, most of which had arbitrary numbers but no common names, and few of which ever entered the mainstream of medicine.

In the course of testing psychoactive drugs in more than a thousand subjects, we did not limit ourselves to estimating the potential usefulness of incapacitating agents. Along the way, we also re-established interest in a long neglected antidote that eventually became generally available in emergency rooms. Ironically, very few doctors who use this drug to treat delirium resulting from medication overdose are aware that Army doctors were the first to study it in a controlled experiment and quietly publish their results in mainstream civilian journals.

In the following pages, the reader will find numerous unvarnished accounts of highly trained soldiers trying to cope with the effects of potent psycho-chemicals – becoming confused and forgetful for hours to days while attentive nurses and psychology technicians carefully measured changes in their ability to function. You will learn the strikingly different ways in which such drugs as BZ, LSD and synthetic marijuana derail thought processes and disorganize behavior. The chapters that follow provide vivid detailed accounts of many bizarre and unexpected incidents, often unearthing forty to fifty year old photographs and videotape transcriptions from my personal files.

Clinical observations are supplemented by verbatim notes made by medical specialists traveling close beside the volunteers on their chemical trips. They recount the bizarre, sometimes wryly amusing, aberrations in speech and behavior sometimes appearing amidst realistic combat simulations. These descriptions clearly illustrate how small doses of a chemical agent can inexorably prevail, despite the high intelligence and thorough training of the subjects. Adding further to the record are the post-test write-ups by the volunteers themselves, which provide unique insights into the subjective side of incapacitation.[It is always in the eye of the beholder,what was incapacitation to the doctor, was called peaking by the tripper.I for one was always amazed at how such a small amount of LSD, could make you a giant of mind DC]

This volume contains frank discussion of the ethical compass that guided our work, particularly with respect to “informed consent.” Some chapters describe, and occasionally take issue with comments appearing in both military and civilian publications, particularly between 1965 and 1982, when public concern about the Army’s testing of drugs in human volunteers dramatically escalated.

Although my own work at Edgewood was primarily dedicated to the evaluation of potential incapacitating agents, this book includes a discussion of nerve agents – the lethal substances that cause the greatest concern. It closes with a personal assessment of the current threat and a critique both of the facts released to the public, and the limitations of our government’s information policies.

What follows is a personal perspective on the clinical study of incapacitating agents investigated in the 1960s. Although in retirement, I felt it important to document the fascinating and informative details of a decade of scientific work might otherwise be lost forever.

Writing what follows required not only vivid recollection of specific events, but close review of previously classified reports, many of them generated while I was still at Edgewood Arsenal. Personal notes, as well as some original data I retained, helped immensely. Most of these exist only in my file cabinets. Interwoven among the names and numbers, are memorable anecdotes, some personal and some that shed light on the dynamics of a military bureaucracy including some political overtones.

Our work took place in a setting where morale was high, curiosity was often rewarded with discovery, and surprisingly strong support was provided by civilian peers, military supervisors and elected officials. Thus, this book often presents an upbeat view of an otherwise somber mission. It frankly recreates the experiences of a psychiatrist who, with much help from others physicians, nurses and technicians, had the unique opportunity to build what eventually became a sophisticated research program.

While focused on experiments, this narrative also depicts the personality of many colleagues. More important, it underlines the patriotism and courage of the many volunteers who trusted us enough to take strange drugs whose effects were not yet fully known. They knew the risks and willingly accepted them. It was the volunteers, more than the researchers, who were the true explorers. They deserve great credit for their starring performance in the offbeat, at times quixotic, drama that took place on a secret stage called Edgewood Arsenal.

For readers, ranging from apolitical scientists, physicians and teachers to ideologues and conspiracy theorists; from historians to incurably inquisitive thinkers; the contents of this book will provide interesting, previously unpublished facts – as well as some new, at times entertaining insights – about an extraordinary decade of now almost forgotten research.

Nowadays, average citizens are somewhat less obsessed with the nuclear threat. Most world leaders likewise seem less preoccupied with the idea that radioactive weapons of mass destruction still pose an imminent danger, although countries such as Iran and North Korea continue to evoke considerable anxiety. Indeed, some unstable nations have stolen or bought the secrets of nuclear bomb making and even brag about their atomic capabilities, hinting darkly that, if provoked, they would not hesitate to use them.

It is interesting to note that even the acronyms for the weapons of mass destruction have changed. We used to be concerned about “NBC” – nuclear, biological and chemical weapons, respectively. Now it is “CBR” – chemical, biological and radiological – devices that provoke the greatest apprehension as we ponder how to plan our defenses. The promotion of “chemical” to the top and the demotion of “nuclear” to the bottom of the list reflect a growing belief – faith may be a more accurate term – that nuclear war is neither highly probable nor easily preventable. A certain degree of fatalism has crept into our national mentality. Many have decided to regard the possibility of nuclear war as too remote to warrant contemplation. The consequences would be too devastating, too unthinkable. If it occurs, it will almost inevitably bring on the final events of our life on earth – hardly worth discussing.

On the other hand, chemical weapons are not particularly difficult to manufacture and armies have actually used them in modern times. Thus, they are now vociferously touted as the most likely threats. Hastily developed detection measures have been deployed in an effort to locate and destroy deadly chemicals before terrorist groups can make use of them. Specially trained dogs now sniff for them in luggage and clothing. An expanding cohort of sophisticated inspectors is learning to hunt for them meticulously, despite mounting costs and annoying inconveniences to travelers. Scientists and engineers are hard at work developing more advanced imaging and analytic equipment capable of visualizing suspicious objects and materials, even when they are concealed within large vehicles and containers.

Modern fear of deadly chemical weapons is engendered by the hideous images of World War I, when countless thousands of courageous troops died helplessly in their trenches, fumes of chlorine, mustard and phosgene sweeping without mercy across their battlements. They clearly knew the nationality of their attackers and could have retaliated in kind, were it not for a woeful lack of comparable weapons. Today, however, the enemy does not align itself with a single nation and no one government can be held responsible for its attacks.

Twentieth century covenants against the use of chemical weapons, such as the Geneva Protocols, now restrain virtually all developed nations. Provisions of the more recent Chemical Warfare Convention (CWC) have further tightened the constraints, outlawing the use of every conceivable chemical weapon. The CWC even bans the use of agents as benign as tear gas (although, ironically, individual nations are not denied the option of using them against dangerous criminals within their own boundaries). And while the CWC prohibitions even extend to drugs and chemicals designed to incapacitate rather than kill, the United States has agreed to abide by them, abandoning the rational argument that prohibition of relatively safe weapons invites more dependence on those that cause more death and suffering.

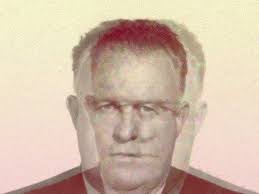

Major General William Creasy

Things were much different back in the late 1950s. In striking

contrast to today’s total ban, the U.S. legislature enthusiastically accepted

the novel concept of incapacitating agents. In 1958, Major General

William Creasy, Chief of the Chemical Corps, was invited to engage this

august branch of government in a lively session. Captivated and at times

even amused by vivid images of a cloud of LSD that could disable well trained

troops without causing them physical harm, senators and

congressmen voted almost unanimously to endorse Creasy’s proposal to

triple the Chemical Corps’ budget and proceed with studies of this and

similar agents in Army volunteers. When asked if he could incapacitate

members of Congress in a similar manner, Creasy cavalierly quipped that

so far he had not considered this necessary! President Dwight Eisenhower quickly gave his blessing to this effort. Later, newly elected President Kennedy, almost from the start of his administration, promoted a “Blue Sky” strategy that included incapacitating agents in the growing list of novel military options. Although, as coming chapters will reveal in detail, subsequent efforts to find and deploy humane chemical weapons were not totally successful, this hopeful objective guided secret research for more than a dozen years. Ultimately, even as hope dwindled, the experimental findings remained locked in tight secrecy for at least another decade.

The Edgewood laboratories eventually filed the wealth of data accumulated during these unorthodox studies, leaving them to languish in closely guarded cabinets. Later they moved these documents to even less accessible archives, determined to keep sensitive, classified reports out of the public limelight. Over time, waning interest and fading memories eroded many details of what we had learned, leaving only sketchy summaries and a significant gap in the historical record. This book goes back four decades in an effort to fill that gap.

By the time news writers began to report the story in more detail, the program had already begun to wind down. After 1970, the search for a militarily acceptable incapacitating agent had become increasingly out of fashion.

The years passed and the activities that took place in the Edgewood Arsenal medical laboratories during that decade were soon only vaguely remembered by a few of the former researchers. Civilian commentators sometimes spoke of the Edgewood program as a rather unethical, ill advised and generally sub-standard scientific effort that had yielded little of interest to the field of medicine. The erroneous belief that the program was primarily the brainchild of the CIA, already notorious for its ill-conceived attempts in the early 1950s to gain control of human behavior with drugs, added to these unflattering characterizations. Most participating physicians failed to rise to the defense and refused to grant interviews to investigative reporters, or shifted responsibility to their attorneys. Drawn by the scent of malfeasance, popular authors began to write books incriminating both the CIA and the Edgewood doctors.

The Edgewood Arsenal program and the earlier shady CIA experiments, involving surreptitiously administered LSD and related drugs, became indelibly linked in the public imagination.

By the time the original detailed technical reports were declassified (usually at least 12 years after they had first been distributed as restricted documents), most of those who had done the work had quietly moved on. Memories were vague, original data largely inaccessible, and motivation to publish them virtually non-existent. As the first Regular Army psychiatrist ever assigned to Edgewood Arsenal, I was only one of a small but growing number Army physicians actively involved in the drug testing.

For ten years, I was given the opportunity to play a leadership role in the search for a safe and effective incapacitating agent. The research design was embryonic in 1961, but slowly evolved into a highly structured method for evaluating candidate agents in Army volunteers. I was engaged in measuring the clinical effects of more than a dozen compounds, most of which had arbitrary numbers but no common names, and few of which ever entered the mainstream of medicine.

In the course of testing psychoactive drugs in more than a thousand subjects, we did not limit ourselves to estimating the potential usefulness of incapacitating agents. Along the way, we also re-established interest in a long neglected antidote that eventually became generally available in emergency rooms. Ironically, very few doctors who use this drug to treat delirium resulting from medication overdose are aware that Army doctors were the first to study it in a controlled experiment and quietly publish their results in mainstream civilian journals.

In the following pages, the reader will find numerous unvarnished accounts of highly trained soldiers trying to cope with the effects of potent psycho-chemicals – becoming confused and forgetful for hours to days while attentive nurses and psychology technicians carefully measured changes in their ability to function. You will learn the strikingly different ways in which such drugs as BZ, LSD and synthetic marijuana derail thought processes and disorganize behavior. The chapters that follow provide vivid detailed accounts of many bizarre and unexpected incidents, often unearthing forty to fifty year old photographs and videotape transcriptions from my personal files.

Clinical observations are supplemented by verbatim notes made by medical specialists traveling close beside the volunteers on their chemical trips. They recount the bizarre, sometimes wryly amusing, aberrations in speech and behavior sometimes appearing amidst realistic combat simulations. These descriptions clearly illustrate how small doses of a chemical agent can inexorably prevail, despite the high intelligence and thorough training of the subjects. Adding further to the record are the post-test write-ups by the volunteers themselves, which provide unique insights into the subjective side of incapacitation.[It is always in the eye of the beholder,what was incapacitation to the doctor, was called peaking by the tripper.I for one was always amazed at how such a small amount of LSD, could make you a giant of mind DC]

This volume contains frank discussion of the ethical compass that guided our work, particularly with respect to “informed consent.” Some chapters describe, and occasionally take issue with comments appearing in both military and civilian publications, particularly between 1965 and 1982, when public concern about the Army’s testing of drugs in human volunteers dramatically escalated.

Although my own work at Edgewood was primarily dedicated to the evaluation of potential incapacitating agents, this book includes a discussion of nerve agents – the lethal substances that cause the greatest concern. It closes with a personal assessment of the current threat and a critique both of the facts released to the public, and the limitations of our government’s information policies.

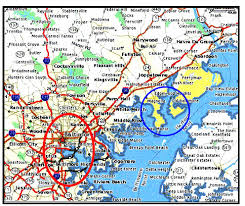

Edgewood Arsenal, now part of the

larger

Aberdeen Proving Grounds

For many years, it was my intent to summarize our psychochemical

inquiries in the 1960s – a unique decade of experimentation. Predictably, other

activities supervened. But when events in the Middle East reawakened world concern about chemical warfare, I felt an obligation to carry out

this long postponed intention. What follows is a personal perspective on the clinical study of incapacitating agents investigated in the 1960s. Although in retirement, I felt it important to document the fascinating and informative details of a decade of scientific work might otherwise be lost forever.

Writing what follows required not only vivid recollection of specific events, but close review of previously classified reports, many of them generated while I was still at Edgewood Arsenal. Personal notes, as well as some original data I retained, helped immensely. Most of these exist only in my file cabinets. Interwoven among the names and numbers, are memorable anecdotes, some personal and some that shed light on the dynamics of a military bureaucracy including some political overtones.

Our work took place in a setting where morale was high, curiosity was often rewarded with discovery, and surprisingly strong support was provided by civilian peers, military supervisors and elected officials. Thus, this book often presents an upbeat view of an otherwise somber mission. It frankly recreates the experiences of a psychiatrist who, with much help from others physicians, nurses and technicians, had the unique opportunity to build what eventually became a sophisticated research program.

While focused on experiments, this narrative also depicts the personality of many colleagues. More important, it underlines the patriotism and courage of the many volunteers who trusted us enough to take strange drugs whose effects were not yet fully known. They knew the risks and willingly accepted them. It was the volunteers, more than the researchers, who were the true explorers. They deserve great credit for their starring performance in the offbeat, at times quixotic, drama that took place on a secret stage called Edgewood Arsenal.

For readers, ranging from apolitical scientists, physicians and teachers to ideologues and conspiracy theorists; from historians to incurably inquisitive thinkers; the contents of this book will provide interesting, previously unpublished facts – as well as some new, at times entertaining insights – about an extraordinary decade of now almost forgotten research.

2

INCAPACITATING THE ENEMY:

STRANGE FRUIT AND

STRAY SMOKE

Chemical warfare has its roots in antiquity. Periodically, armies have used

drugs, mostly extracted from poisonous plants, against their opponents. In more

recent centuries, chemical laboratories have gone on to produce new and more

sophisticated compounds along with more effective devices for their delivery.

The American army paid little or no attention to this type of weapon, however,

until the 20th century. When German troops used toxic gases in World War I,

they found the U.S. and its allies almost totally unprepared.

Although chemical warfare goes back at least 3,000 years, its use has

always been sporadic and short-lived. Ingenious attempts to find effective

substances and ways to deliver them in the battlefield almost always failed. On the rare occasions when they proved effective, the parties involved often agreed

to ban them in the future. The agreements, however, were never international in

scope and opinions differed as to whether or not to outlaw chemical weapons.

For every condemnation of their use, there were countervailing arguments in

their favor.

The effects of lethal chemical weapons are, of course, abhorrent, even when they account for only a small fraction of the total number of killed and wounded. When toxic chemicals strike, they tend to annihilate specific groups rather than scattered victims. Historically, victory is supposed to go to the courageous and most skilled, but chemicals make courage and training irrelevant, leaving no heroes. Eerily, most deaths resulting from lethal chemical agents leave corpses without wounds. The victims of gas attacks rarely go down in legend.

For these reasons and no doubt others, it has generally been the most despotic and underdeveloped nations that have had the least compunction about their use. In more “advanced” countries, certain “noble traditions” of warfare seem to have created a natural aversion to anonymous killing by poison, the use of which is usually associated with cowardice and treachery. Accordingly, it has generally proven useless to argue as some military experts did (especially after WW I) that war was not “playing marbles” and if chemical weapons could achieve victory more swiftly and with less loss of life, they should be used. (In WW II, a similar line of reasoning ultimately prevailed. President Truman unleashed the atomic bomb for that very purpose – to conclude a war and avert useless deaths on the battlefield.)

Attempts to ban chemical warfare always fell short of success. Even though the United States signed the 1925 Geneva Protocol, the Senate would not ratify it.

After World War I, some military analysts pointed out that we should have taken the threat of chemical attack more seriously. Had we provided gas masks and training to our troops, tens of thousands of dead soldiers could have remained alive. Many thousands more (unless exposed to blister agents) “could have lived out their lives free of painful disabilities. In a 1932 letter to Secretary of State Henry L. Stinson, US Army Chief of Staff General Douglas MacArthur argued that staying abreast of technical advances in the field required continuing research and testing. As with nuclear weapons, many asserted that a retaliatory chemical capability was necessary to make aggressors think twice before using such weapons.

Recognizing our earlier naiveté, the War Department established the Chemical Corps in 1922, centered at Edgewood Arsenal in Maryland. Over the next forty years, the U.S. escaped a repetition of the chemical atrocities of the First World War. Ironically, it was mostly Hitler’s personal phobia of chemical retaliation that saved us from the thousands of tons of nerve agents already synthesized and stockpiled by the Nazis.

In the 1950s, heightened awareness of the threat led to renewed U.S. efforts to build a sturdy chemical defense, including improved methods of training, detection, protection, decontamination and treatment, along with contingency stockpiling of the very nerve agents we almost faced in WW II. Although we subsequently armed ourselves with similar weapons, we made it clear that we would never use them first. Franklin Roosevelt, in particular, emphatically stated that chemical weapons were despicable. Accordingly, the policy of no “first use” became an axiom of military planning.

Jeffery Smart has described the 1960s as the “decade of turmoil” in the Chemical Corps. During this period, the U.S. made serious efforts to develop a new class of weapons: the “incapacitants” – otherwise referred to as “non-lethal agents.” And it is here that this book picks up the story.

While the term “incapacitating agent” seems to have first appeared in the 20th century, the concept is extremely old. Not only have armies used chemical weapons against both enemy troops and civilians, but criminals have also employed chemical agents to simplify robberies or to buy extra time necessary to carry out complex illegal activities.

Historical incidents illustrate various attempts to use drugs in a military setting. Some of the substances used bear a striking similarity to modern chemical weapons and provide useful illustrations of their potential military effects. As we initiated our own research at Edgewood Arsenal in 1961, we concentrated on incapacitants, focusing on anticholinergic (atropine-like) drugs. A review of the existing literature seemed like a good place to start. We asked Ephraim Goodman, a psychologist in our clinical laboratory, to search for historical records of the behavioral effects of high doses of atropine and similar agents. He scoured the stacks in several libraries and after several weeks submitted a draft report that exhaustively summarized both military and non-military uses of atropine to produce either intoxication or death.

Physicians have, of course, used atropine for many centuries as treatment for a variety of conditions. Therapeutic doses generally range from 0.5 to 2.0 mg. At doses above 10 mg, atropine causes profound mental changes. Following massive overdose (above 100 mg), the outcome can be lethal.

Goodman visited the Library of Congress and other archives in his persistent search. He waded through 100 years of The Journal of the American Medical Association, as well as The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal (continued as The New England Journal of Medicine), Lancet and The British Medical Journal.

His fluency in German also allowed him to review other specialized sources in detail, including Fuehrer-Wielands Sammlung von Vergiftungsfällen (continued as Archiv für Toxicologie) from 1930 to 1962 and Deutsche Zeitschrift für die Gesamte Gerichtliche Medizin from 1922 through 1939. An examination of standard medical literature indices from 1880 to the present reveals additional major reports in other sources. Never published, Goodman's draft manuscript nevertheless remains a treasure trove of incapacitating agent history, extracted from more than 300 articles both for medicinal and non-medicinal purposes. The latter include robbery, seduction, Satanism, tribal justice by ordeal, location of precious objects and stolen articles, individual thrill-seeking and practical joking. With more positive intent, these plants were revered by some primitive religions and were sometimes used to initiate youths into adulthood.

Accidental overdoses were especially common. Of 576 cases of atropine intoxication, almost half were due to oral ingestion of plant material, particularly by children below the age of five. Ophthalmological, liquid medicinal, parenteral and percutaneous overdoses made up the remainder. Significant differences in the source of the drug occurred among age groups, however. Individuals above the age of 61, for example, were inclined to encounter overdosage from eye drops or medicinal plasters.

Although not as common nowadays, in the period from 1950-55, 10% of live admissions of children under five years of age to Scottish hospitals were for intoxication resulting from ingestion of atropine-containing plants. Among pediatric admissions to a South African Hospital during the same period, fully two-thirds were victims of solanaceous alkaloids. Surprisingly, physicians frequently failed to recognize that atropine was the basis for the clinical features they observed. Often, they wrongly attributed the signs and symptoms to syphilitic paresis, postpartum psychosis, dementia praecox (schizophrenia), acute manic-depressive psychosis (bipolar disorder), or any of a variety of infectious or traumatic conditions.

The signs and symptoms of atropine intoxication have been wryly summarized by H. P. Morton (1939), in the form of five easy to remember similes: “Hot as a hare, Blind as a bat, Dry as a bone, Red as a beet and Mad as a hen.” In more professional language, atropine intoxication (as observed by Forrer and Miller during their atropine coma treatments in the late 1940s) consists of two sequences: the first neurological, the second, behavioral.

The neurological sequence, according to these clinicians, is as follows:

1) Progressive muscular incoordination 2) Decreased pain sensitivity 3) Hyperreflexia with development of a Babinski sign (upward motion of the big toe following stimulation of the sole of the foot).

The behavioral sequence is as follows:

1) Clouding of the sensorium 2) Disorientation 3) Loss of time-space relationships 4) Distortion of perception with illusions and hallucinations 5) Confusion 6) Coma. (The last of these usually appears only following large overdoses.)

Historians have described the consequences of mass intoxication as early as in the last half-century BC, when Antony's army was exposed to belladonna by an enemy force and experienced both delirium and deaths, according to Plutarch and case reports. A summary of some of his findings follows.

“They chanced upon an herb that was mortal, first taking away all sense and understanding. He that had eaten of it remembered nothing in the world, and employed himself only in moving great stones from one place to another, which he did with as much earnestness and industry as if it had been a business of the greatest consequence. Through all the camp there was nothing to be seen but men grubbing upon the ground at stones, which they carried from place to place.”

As a result of the widespread global distribution of solanaceous plants (atropine containing members of the potato family), a variety of cultures have employed them. Similar poisoning occurred among Colonial troops in Virginia in 1676. The affected soldiers needed confinement for eleven days (a surprisingly long period). On 14 September 1813, while on the march, a company of French Infantry unknowingly consumed atropine-containing berries. Poisoning of monks in a monastery around the same time disrupted their well-learned and habitual rituals. A group of sailors, intoxicated while on board ship in April 1792, was fortunately able to call for help by firing cannons and running up signal flags, allowing some to survive.

The following excerpt describes the delirious condition in the case of eight East Indian troops poisoned in 1895:

“Most of them were unable to answer when spoken to, and those who could, had forgotten their own names. Some lay on the ground in a dazed condition; others sat up constantly making fidgety movements with their fingers, picking up small particles of sand or pebbles from the ground or appearing to be searching for something they had lost, and occasionally looking up with a half vacant, half-wild expression.”

Similarly, the French soldiers who poisoned themselves in 1813 by naïvely consuming wild berries containing solanaceous alkaloids also soon became delirious. M. Gaultier, the attending military physician, described the victims as:

“...in continual agitation. Their knees sank under the weight of the body, inclining them forwards, and carrying their trembling hands towards the earth, endeavoring to collect little stones and bits of wood, which they always let fall or threw away to recommence the same pursuit.”

Goodman comments that this grubbing on the ground was typical behavior in belladonna-intoxicated children, as well as adults. (In later chapters, BZ intoxicated volunteers will be seen to exhibit very similar behaviors.)

Age, health and environmental factors appear to play a significant role in the susceptibility to, and potential lethality of atropine toxicity. The very young and the old as well as those with debilitating conditions such as tuberculosis or hypoglycemia, are especially vulnerable. The presence of a hot, dry environment increases the danger of death through hyperthermia. Belladonna drugs inhibit the ability to perspire, the cause of most of the deaths in hot climates. In cases of extreme overdose, cardiac failure is probably the determining factor.

It is difficult to estimate the lethal dose in man due to the many confounding factors that may be present, as well as the selective reporting of deaths following either unusually high or low dosage (both of which probably have more medical “news value”). One authority has declared a “surely fatal dose” to be about 1200 mg. Most pharmacology texts, on the other hand, tend to give estimates at least ten times lower.

Based on pooled data, Goodman calculated that 450 mg is the average lethal dose (LD50), about forty-five times the dose that produces delirium. One report in the literature documents a case of recovery from an oral dose of 1,000 mg of atropine. Also, at least one individual has survived 500 mg (from 100 to 150 times the delirium-producing dose) of the related but more potent drug scopolamine.

The military mass intoxications mentioned above were mostly accidental. But in his review, Goodman also includes a history of the deliberate military use of atropine and atropine-like substances, i.e., hyoscyamine (atropine) and hyoscine (scopolamine), both obtainable from plant sources. In one instance:

“An officer in Hannibal's Army, about 200 BC, used atropa mandragora (mandrake) as a chemical ambush. According to the officer, "Maharbal, sent by the Carthaginians against the rebellious Africans, knowing that the tribe was passionately fond of wine, mixed a large quantity of wine with mandragora which in potency is something between a poison and a soporific. Then, after an insignificant skirmish, he deliberately withdrew. At dead of night, leaving in the camp some of his baggage and all the drugged wine, he feigned flight. When the barbarians captured the camp and in frenzy of delight greedily drank the drugged wine, Maharbal returned, and either took them prisoners or slaughtered them while they lay stretched out as if dead.”

In the struggle for power between Pompey and Caesar (in approximately 50 BC) troops in Africa were deliberately poisoned by placing substances in their drinking water. Subsequently “their vision became hazy, as in a fog, and an invincible sleep overtook them. Then followed vomiting and jerking of the whole body.” L. Lewin (1929), an expert on psychoactive plants, believes that their difficulties in visual accommodation, muscular excitation and desire for sleep clearly point to intoxication by solanaceae. The widely distributed Hyoscyamus falezlez and Hyoscyamus muticus are indigenous to North Africa and may have been the plant material used to drug the troops.

The next documented example of the use of solanaceae for military purposes apparently did not occur until nearly eleven hundred years later:

“In the reign of Duncan 1034-1040 AD., the eighty -fourth King of Scotland, Swain, or Sweno, King of Norway, landed his army in Fife. The Scots retreated to Perth after a battle near Culross. Duncan sent messengers to Sweno to negotiate surrender and during the discussions supplied the Norwegians with provisions. As expected, this was looked upon as a sign of weakness. The Scottish forces under Bancho entered Sweno's camp while the invaders were intoxicated with wine dosed with ‘sleepy nightshade.” (G. Buchanan, 1831).

Historical evidence of the oral use of the solanaceae for military purposes next exhibits another gap, of over eight hundred years.

“In 1881 a peaceful railway surveying expedition under Lieutenant-Colonel Paul Flatters of France was proceeding to the Sudan from Algeria, through the territory of the Touareg. These Berbers who, unlike other North Africans, veil the men and not the women are a raider people who did not completely surrender to French authorities until 1943. The Touareg call themselves "The Blue Men" and "The People of the Veil"; the other inhabitants, however, call them ‘The Abandoned of God.’“ Flatters ignored a warning letter and marched into an ambush on 16 February 1881, losing approximately half of his force, or all of the personnel in the area where the ambush took place. On the next day, the five French and fifty-one indigenous survivors started to march to a French outpost. This party was trailed by a force of approximately two hundred Touareg.

“On 8 March 1881, their supplies having been observed to be low, they were approached by three men who claimed to be members of another tribe. These men offered to sell the party provisions. On the next day, three bundles of dried dates were thrown into the camp, and varying quantities were consumed. The French members of the party apparently ate more than the indigenous soldiers.

“Shortly thereafter signs and symptoms of solanaceous intoxication were manifested. Five of the fifty-six men disappeared in the confusion of the first few minutes. Thirty-one of the remainder were so sick that they were unable to look after themselves. In the evening, some attempted to crawl away into the desert. The Frenchmen had been tied down by the senior indigenous soldier to prevent injury. There was some improvement by morning.” According to R. Leder (1934), “And so they set off, half mad, bent double under excruciating pain, their legs crumbling away under them, their voices shrill, their words unintelligible.

“On the second day after the poisoning they reached an oasis, where a force of Touareg awaited them. By this time, however, the survivors were able to function as an effective fighting force, and thus the attack was repulsed. Two of the French, said to be under the influence of the drug, rose and marched forward to death.

“After more difficulties, the party evaded the Touareg and found water. They

resorted to cannibalism to sustain life. On 29 March 1881, twelve Algerian

soldiers reported to a French outpost. The poison has been identified as

Hyoscyamus falezlez.”

“After more difficulties, the party evaded the Touareg and found water. They

resorted to cannibalism to sustain life. On 29 March 1881, twelve Algerian

soldiers reported to a French outpost. The poison has been identified as

Hyoscyamus falezlez.”

Other examples cited by Goodman include the poisoning of 200 French soldiers by Chinese reformers in Hanoi on 27 June 1908, all of whom recovered. One of the intoxicated soldiers saw ants on his bed, a second fled to a tree to escape from a hallucinated tiger and a third took aim at birds in the sky. Another incident was the abortive attempt by Soviet agents in 1959 to poison the staff of Radio Free Europe in Munich by putting atropine in saltshakers in the cafeteria. A double agent foiled this effort.

An example of an early attempt to disseminate belladonna alkaloids as an “aerosol” occurred on 29 July 1672, when troops of the Bishop of Muenster assaulted the city of Gröningen. It proved fruitless. The fumes dissipated in the open air, and the heat of combustion destroyed the active principles of the vegetable poisons contained within the shells. Despite the ineffectiveness of this weapon, the French and Germans soon negotiated a treaty at Strasburg on 27 August 1675, outlawing the use of poisoned shells.