It bothers me,definitely not great here,the decaying of the nation from the top down can be seen here,destroyed a man who cared for his nation,allied with the man and his ideology,FDR screwed the American people,and half of Europe.Even their own people did not want to return

Hellstorm The Death of Nazi Germany

1944–1947

by Thomas Goodrich

8

Unspeakable

German Wehrmacht! My comrades! The Fuhrer has fallen. True to his great concept of protecting the people of Europe from Bolshevism, he put his life on the line and died a hero’s death. With him one of the greatest heroes of German history is gone. . . .

The Fuhrer has appointed me to be his successor. . . . I assume command of all services of the German Wehrmacht with the desire to continue the fight against the Bolsheviks until the fighting troops and the hundreds of thousands of families of the eastern German region have been saved from enslavement or destruction. I must continue the fight against the British and the Americans for as long as they try to impede my struggle against the Bolsheviks. . . . Anyone who evades his duty now, and thus condemns German women and children to death or enslavement, is a coward and a traitor....

German soldiers, do your duty. The life of our nation depends upon it!

Karl Donitz,

Grand Admiral 1

When survivors reached the broad Elbe, American forces under Eisenhower prevented a crossing. Although German soldiers were allowed to pass over and surrender, the general refused civilians the same right. When Soviet aircraft soon appeared, the Americans were forced back to avoid the bombing. Hence, three hundred thousand panic-stricken refugees risked the river and ultimately reached the west bank. Those thousands left standing on the opposite shore were abandoned to their fate.3

Unlike the Americans, British forces under Bernard Montgomery allowed all Germans, soldiers and civilians alike, to find haven within its lines. Horrified by what he had seen and heard, the field marshal’s manly act saved thousands of women and children from rape, torture and death.

“The Russians,” Montgomery later wrote, “though a fine fighting race, were in fact barbarous Asiatics.”4

When refugees did not come to the British, the British came to them. In the first days of May, Montgomery’s men swept upward to occupy northern Germany. Although the English encountered fanatical opposition from small SS units at Bremen, the people of that port were overjoyed; not only would the bombs stop falling but they were saved from the Soviets.

“Their relief that no battle was to be fought over their heads was

such that soon we were being hailed as liberators,” remembered one

Tommy.5

Expecting a bloodbath similar to Berlin, when Montgomery’s troops

reached Germany’s second largest city, they were mystified. Noted a

nervous Richard Brett-Smith as he rumbled in an armored car through

the streets of Hamburg:

There was something unnatural about the silence, something a little uncanny. As we drove up to that last great bridge across the Elbe, the final obstacle that could have held us up so long, it seemed impossible that we had taken Hamburg so easily. Looking down at the cold gray waters of the Elbe swirling far below, we sensed again that queer feeling that came whenever we crossed an enemy bridge, and it would have been no great surprise if the whole structure had suddenly collapsed. . . . But no, it did not blow up . . . we were across the last obstacle, and there were no more rivers to cross. . . . There was a lot of clicking of heels and saluting, and in a few moments Hamburg, the greatest port of Germany had been surrendered. . . .

We had long guessed how disorganized the enemy was, and that his administration had broken down, but even so, the sight we now saw was stranger than we had ever expected. Thousands of infantry, Luftwaffe men, SS men, antitank gunners, Kriegsmarinen, Hungarians, Romanians, ambulance men, Labour Corps men, Hitler Jugend boys, soldiers of every conceivable age and unit, jostled one another in complete disorder . . . down every road the Wehrmacht struggled to give itself up, its pride broken, its endurance at an end.6

Other German soldiers, a Canadian officer recalled, “hungry and frightened, were lying in grain fields within fifty feet of us, awaiting the appropriate time to jump up with their hands in the air.”7

For those Landsers who had fought for years in the savage, no-quarter nightmare that was the East Front, the first act of surrender, even to the Western Allies, was the most difficult and unnatural step in the world to take. Guy Sajer:

Two of our men stood up, with their hands raised. . . . We wondered what would happen next. Would English machine guns cut them down? Would our leader shoot them himself, for giving up like that? But nothing happened. The old man, who was still beside me, took me by the arm, and whispered: “Come on. Let’s go.”

We stood up together. Others quickly followed us. . . . We walked towards the victors with pounding hearts and dry mouths....

There was something unnatural about the silence, something a little uncanny. As we drove up to that last great bridge across the Elbe, the final obstacle that could have held us up so long, it seemed impossible that we had taken Hamburg so easily. Looking down at the cold gray waters of the Elbe swirling far below, we sensed again that queer feeling that came whenever we crossed an enemy bridge, and it would have been no great surprise if the whole structure had suddenly collapsed. . . . But no, it did not blow up . . . we were across the last obstacle, and there were no more rivers to cross. . . . There was a lot of clicking of heels and saluting, and in a few moments Hamburg, the greatest port of Germany had been surrendered. . . .

We had long guessed how disorganized the enemy was, and that his administration had broken down, but even so, the sight we now saw was stranger than we had ever expected. Thousands of infantry, Luftwaffe men, SS men, antitank gunners, Kriegsmarinen, Hungarians, Romanians, ambulance men, Labour Corps men, Hitler Jugend boys, soldiers of every conceivable age and unit, jostled one another in complete disorder . . . down every road the Wehrmacht struggled to give itself up, its pride broken, its endurance at an end.6

Other German soldiers, a Canadian officer recalled, “hungry and frightened, were lying in grain fields within fifty feet of us, awaiting the appropriate time to jump up with their hands in the air.”7

For those Landsers who had fought for years in the savage, no-quarter nightmare that was the East Front, the first act of surrender, even to the Western Allies, was the most difficult and unnatural step in the world to take. Guy Sajer:

Two of our men stood up, with their hands raised. . . . We wondered what would happen next. Would English machine guns cut them down? Would our leader shoot them himself, for giving up like that? But nothing happened. The old man, who was still beside me, took me by the arm, and whispered: “Come on. Let’s go.”

We stood up together. Others quickly followed us. . . . We walked towards the victors with pounding hearts and dry mouths....

We were roughly jostled together, and shoved into place by English soldiers

with vindictive faces. However, we had seen worse in our own army, particularly

in training. . . . The roughness with which the English handled us seemed comparatively

insignificant, and even marked by a certain kindness.8

“In a time of total chaos,” said an appreciative German, “only the British will still act like gentlemen.”9

Though right on most counts, a number of ugly incidents did occur, illustrating that the Englishman was not immune to the years of vicious anti-German propaganda.

On May 3, RAF fighter-bombers attacked and sank the German refugee ship Cap Arkona as it neared Lubeck Bay. Among the thousands of drowning victims were large numbers of concentration camp inmates from Poland. When the British captured Lubeck a short time later and saw hundreds of corpses washing up on shore or bobbing in the bay, it seemed a clear case of the Nazi brutality the world had heard so much about. As Field Marshal Ernst Milch, in full military attire, stepped forward to formally surrender the garrison, an outraged English commando jerked the general’s heavy baton from his hand and beat him savagely over the head.10

“In a time of total chaos,” said an appreciative German, “only the British will still act like gentlemen.”9

Though right on most counts, a number of ugly incidents did occur, illustrating that the Englishman was not immune to the years of vicious anti-German propaganda.

On May 3, RAF fighter-bombers attacked and sank the German refugee ship Cap Arkona as it neared Lubeck Bay. Among the thousands of drowning victims were large numbers of concentration camp inmates from Poland. When the British captured Lubeck a short time later and saw hundreds of corpses washing up on shore or bobbing in the bay, it seemed a clear case of the Nazi brutality the world had heard so much about. As Field Marshal Ernst Milch, in full military attire, stepped forward to formally surrender the garrison, an outraged English commando jerked the general’s heavy baton from his hand and beat him savagely over the head.10

☠☠☠

While the British were mopping up huge areas to the north, Americans

were doing the same further south. For the most part, US forces

were also greeted with white flags, cheers and tears of relief from a warweary

populace. When the Americans did meet determined defenders,

it was often small pockets of old men and little boys. Reflected a

GI: “I could not understand it, this resistance, this pointless resistance

to our advance. The war was all over—our columns were spreading

across the whole of Germany and Austria. We were irresistible.

We could conquer the world; that was our glowing conviction. And

the enemy had nothing. Yet he resisted and in some places with an

implacable fanaticism.”11

Those defenders who survived to surrender were often mowed down

where they stood. Gustav Schutz remembered stumbling upon one

massacre site where a Labor Service unit had knocked out several

American tanks.

“More than a hundred dead Labor Service men were lying in long rows—all with bloated stomachs and bluish faces,” said Schutz. “We had to throw up. Even though we hadn’t eaten for days, we vomited.”12

Already murderous after the Malmedy Massacre and the years of anti-German propaganda, when US forces entered the various concentration camps and discovered huge piles of naked and emaciated corpses, their rage became uncontrollable. As Gen. Eisenhower, along with his lieutenants, Patton and Bradley, toured the prison camp at Ohrdruf Nord, they were sickened by what they saw. In shallow graves or lying haphazardly in the streets were thousands of skeleton-like remains of German and Jewish prisoners, as well as gypsies, communists, and convicts.

“I want every American unit not actually in the front lines to see this place,” ordered Eisenhower. “We are told that the American soldier does not know what he is fighting for. Now, at least, he will know what he is fighting against.”13

“In one camp we paraded the townspeople through, to let them have a look,” a staff officer with Patton said. “The mayor and his wife went home and slashed their wrists.”

“Well, that’s the most encouraging thing I’ve heard,” growled Eisenhower, who immediately wired Washington and London, urging government and media representatives to come quickly and witness the horror for themselves.14

Given the circumstances, the fate of those Germans living near this and other concentration camps was as tragic as it was perhaps predictable. After compelling the people to view the bodies, American and British officers forced men, women and children to dig up with their hands the rotting remains and haul them to burial pits. Wrote a witness at one camp:

All day long, always running, men and women alike, from the death pile to the death pit, with the stringy remains of their victims over their shoulders. When one of them dropped to the ground with exhaustion, he was beaten with a rifle butt. When another stopped for a break, she was kicked until she ran again, or prodded with a bayonet, to the accompaniment of lewd shouts and laughs. When one tried to escape or disobeyed an order, he was shot.15

For those forced to handle the rotting corpses, death by disease often followed soon after.

Few victors, from Eisenhower down, seemed to notice, and fewer seemed to care, that conditions similar to the camps existed throughout much of Germany. Because of the almost total paralysis of the Reich’s roads and rails caused by around-the-clock air attacks, supplies of food, fuel, clothes, and medicine had thinned to a trickle in German towns and cities and dried up almost entirely at the concentration camps. As a consequence, thousands of camp inmates swiftly succumbed in the final weeks of the war to typhus, dysentery, tuberculosis, starvation, and neglect.16 When pressed by a friend if there had indeed been a deliberate policy of starvation, one of the few guards lucky enough to escape another camp protested:

“It wasn’t like that, believe me; it wasn’t like that! I’m maybe the only survivor who can witness to how it really was, but who would believe me!”

“Is it all a lie?”

“Yes and no,” he said. “I can only say what I know about our camp. The final weeks were horrible. No more rations came, no more medical supplies. The people got ill, they lost weight, and it kept getting more and more difficult to keep order. Even our own people lost their nerve in this extreme situation. But do you think we would have held out until the end to hand the camp over in an orderly fashion if we had been these murderers?”17

As American forces swept through Bavaria toward Munich in late April, most German guards at the concentration camp near Dachau fled. To maintain order and arrange an orderly transfer of the 32,000 prisoners to the Allies, and despite signs at the gate warning, “no entrance—typhus epidemic,” several hundred German soldiers were ordered to the prison.18 When American units under Lt. Col. Felix Sparks liberated the camp the following day, the GIs were horrified by what they saw. Outside the prison were rail cars brim full with diseased and starved corpses. Inside the camp, Sparks found “a room piled high with naked and emaciated corpses. As I turned to look over the prison yard with unbelieving eyes, I saw a large number of dead inmates lying where they had fallen in the last few hours or days before our arrival. Since all the many bodies were in various stages of decomposition, the stench of death was overpowering.”19

Unhinged by the nightmare surrounding him, Sparks turned his equally enraged troops loose on the hapless German soldiers. While one group of over three hundred were led away to an enclosure, other disarmed Landsers were murdered in the guard towers, the barracks, or chased through the streets. US Army chaplain, Captain Leland Loy:

A German guard came running toward us. We grabbed him and were standing there talking to him when . . . a GI came up with a tommy-gun. He grabbed the prisoner, whirled him around and said,“There you are you son-of-a-bitch!!” The man was only about three feet from us, but the soldier cut him down with his sub-machine gun. I shouted at him, “what did you do that for, he was a prisoner?” He looked at me and screamed “Gotta kill em, gotta kill em.” When I saw the look in his eyes and the machine gun waving in the air, I said to my men, “Let him go.” 20

“The men were deliberately wounding guards,” recalled one US soldier. “A lot of guards were shot in the legs so they couldn’t move. They were then turned over to the inmates. One was beheaded with a bayonet. Others were ripped apart limb by limb.”21

While the tortures were in progress, Lt. Jack Bushyhead forced nearly 350 prisoners up against a wall, planted two machine-guns, then ordered his men to open fire. Those still alive when the fusillade ended were forced to stand amid the carnage while the machine-gunners reloaded. A short time later, army surgeon Howard Buechner happened on the scene:

Lt. Bushyhead was standing on the flat roof of a low building....Beside him one or more soldiers manned a .30 caliber machine gun. Opposite this building was a long, high cement and brick wall. At the base of the wall lay row on row of German soldiers, some dead, some dying, some possibly feigning death. Three or four inmates of the camp, dressed in striped clothing, each with a .45 caliber pistol in hand, were walking along the line. . . . As they passed down the line, they systematically fired a round into the head of each one.22

“At the far end of the line of dead or dying soldiers,” Buechner continued, “a small miracle was taking place.”

The inmates who were delivering the coup de grace had not yet reached this point and a few guards who were still alive were being placed on litters by German medics. Under the direction of a German doctor, the litter bearers were carrying these few soldiers into a nearby hospital for treatment.

I approached this officer and attempted to offer my help. Perhaps he did not realize that I was a doctor since I did not wear red cross insignia. He obviously could not understand my words and probably thought that I wanted him to give up his patients for execution. In any event, he waved me away with his hand and said “Nein,” “Nein,” “Nein.”23

Despite his heroics and the placing of his own life in mortal danger, the doctor’s efforts were for naught. The wounded men were soon seized and murdered, as was every other German in the camp.

“We shot everything that moved,” one GI bragged.

“We got all the bastards,” gloated another.

In all, over five hundred helpless German soldiers were slaughtered in cold blood. As a final touch, Lt. Col. Sparks forced the citizens of Dachau to bury the thousands of corpses in the camp, thereby assuring the death of many from disease.24

Though perhaps the worst, the incident at Dachau was merely one of many massacres committed by US troops. Unaware of the deep hatred the Allies harbored for them, when proud SS units surrendered they naively assumed that they would be respected as the unsurpassed fighters that they undoubtedly were. Lt. Hans Woltersdorf was recovering in a German military hospital when US forces arrived.

Those who were able stood at the window, and told those of us who were lying

down what was going on. A motorcycle with sidecar, carrying an officer and two

men from the Waffen-SS, had arrived. They surrendered their weapons and

the vehicle. The two men were allowed to continue on foot, but the officer was

led away by the Americans. They accompanied him part of the way, just fifty

meters on. Then a salvo from submachine guns was heard. The three Americans

returned, alone.

Those who were able stood at the window, and told those of us who were lying

down what was going on. A motorcycle with sidecar, carrying an officer and two

men from the Waffen-SS, had arrived. They surrendered their weapons and

the vehicle. The two men were allowed to continue on foot, but the officer was

led away by the Americans. They accompanied him part of the way, just fifty

meters on. Then a salvo from submachine guns was heard. The three Americans

returned, alone.

“Did you see that? They shot the lieutenant! Did you see that? They’re shooting all the Waffen-SS officers!”

That had to be a mistake! Why? Why?!

Our comrades from the Wehrmacht didn’t stand around thinking for long. They went down to the hospital’s administrative quarters, destroyed all files that showed that we belonged to the Waffen-SS, started new medical sheets for us with Wehrmacht ranks, got us Wehrmacht uniforms, and assigned us to new Wehrmacht units.25

Such stratagems seldom succeeded, however, since SS soldiers had their blood-type tattooed under the left arm.

“Again and again,” continues Woltersdorf, “Americans invaded the place and gathered up groups of people who had to strip to the waist and raise their left arm. Then we saw some of them being shoved on to trucks with rifle butts.”26

When French forces under Jacques-Philippe Leclerc captured a dozen French SS near Karlstein, the general sarcastically asked one of the prisoners why he was wearing a German uniform.

“You look very smart in your American uniform, General,” replied the boy.

In a rage, Leclerc ordered the twelve captives shot.

“All refused to have their eyes bandaged,” a priest on the scene noted, “and all bravely fell crying “Vive la France!”27

Although SS troops were routinely slaughtered upon surrender, anyone wearing a German uniform was considered lucky if they were merely slapped, kicked, then marched to the rear. “Before they could be properly put in jail,” wrote a witness when a group of little boys were marched past, “American GIs . . . fell on them and beat them bloody, just because they had German uniforms.”28

After relatively benign treatment by the British, Guy Sajer and other Landsers were transferred to the Americans. They were, said Sajer,“tall men with plump, rosy cheeks, who behaved like hooligans.”

Their bearing was casual. . . . Their uniforms were made of soft cloth, like golfing clothes, and they moved their jaws continuously, like ruminating animals. They seemed neither happy nor unhappy, but indifferent to their victory, like men who are performing their duties in a state of partial consent, without any real enthusiasm for them. From our filthy, mangy ranks, we watched them with curiosity. . . . They seemed rich in everything but joy....

The Americans also humiliated us as much as they could. . . . They put us in a camp with only a few large tents, which could shelter barely a tenth of us.... In the center of the camp, the Americans ripped open several large cases filled with canned food. They spread the cans onto the ground with a few kicks, and walked away.... The food was so delicious that we forgot about the driving rain, which had turned the ground into a sponge....

From their shelters, the Americans watched us and talked about us. They probably despised us for flinging ourselves so readily into such elementary concerns, and thought us cowards for accepting the circumstances of captivity. . . . We were not in the least like the German troops in the documentaries our charming captors had probably been shown before leaving their homeland. We provided them with no reasons for anger; we were not the arrogant, irascible Boches, but simply underfed men standing in the rain, ready to eat unseasoned canned food; living dead, with anxiety stamped on our faces, leaning against any support, half asleep on our feet; sick and wounded, who didn’t ask for treatment, but seemed content simply to sleep for long hours, undisturbed. It was clearly depressing for these crusading missionaries to find so much humility among the vanquished.29

Ironically, it was those very same soldiers who had fought with such ruthless savagery during the war and whose government had not even been a signatory to the Geneva Convention that now often exhibited most kindness and compassion to the fallen foe. Undoubtedly, these battle-hardened Soviet shock troops had seen far too much blood and death during the past four years to thirst for more. Panzer commander, Col. Hans von Luck:

So there we stood with our hands up; from all sides the Russians came at us with their tommy guns at the ready. I saw to my dismay that they were Mongolians, whose slit eyes revealed hatred, curiosity, and greed. As they tried to snatch away my watch and Knight’s Cross, a young officer suddenly intervened.

“Stop, don’t touch him. He’s a geroi (hero), a man to respect.”

I looked at him and just said, “Spasivo (thank you)....

This correct young Russian officer took us at once to the nearest regimental command post, where he handed us over to a colonel of the tank corps. . . . It turned out before long that it had been his tank regiment on which we had inflicted such heavy losses at Lauban. This burly man, who made such a brutal first impression, slapped his thigh and laughed.

“You see,” he cried, “that’s poetic justice: you shot up my tanks and forced us to retreat; now in recompense I have you as my prisoner.”

He fetched two glasses and in Russian style filled them to the brim with vodka, so that together we would drain them with one swallow.30

In numerous other instances surprised Landsers in the east were treated correctly, given food, clothing, cigarettes, and accorded prisoner of war status. Left to the Russian soldiers themselves, there would have been no gulags, no slavery, and no Siberia for their defeated enemy—it was enough for the average Ivan to have simply survived.

“With this signature,” Field Marshal Alfred Jodl announced to the Allies, “the German people and the German armed forces are for better or worse delivered into the victor’s hands. . . . In this hour I can only express the hope that the victors will treat them with generosity.”31

For those resolved to fight to the death as long as their nation fought on, formal capitulation was the signal that they now could lay down their arms with honor in tact. Many, like famous flying ace Hans-Ulrich Rudel, were determined to face the ignominy of defeat with all the dignity they could muster. When the one-legged pilot landed his plane to surrender at an American-occupied airfield, a GI rushed up, poked a pistol into his face, then grabbed for the colonel’s decorations. Rudel promptly slammed the canopy shut. A short time later, as the hobbling ace was escorted to the officers’ mess, other prisoners sprang to their feet and gave the Nazi salute. At this, the indignant US commander demanded silence, then asked Rudel if he spoke English. “Even if I can speak English, we are in Germany and here I speak only German. As far as the salute is concerned, we are ordered to salute that way, and being soldiers, we carry out our orders. Besides, we don’t care whether you object to it or not. The German soldier has not been beaten on his merits but has simply been crushed by overwhelming masses of materiel.”32

For surrendering SS units lucky enough to escape savage beatings or

execution, there were sometimes humiliations worse than death. When

one group of survivors, after six bloody years of war, pinned on their

medals in a final act of pride, they were mobbed by US souvenir seekers

who plucked from them the last vestige of their valor.33

For surrendering SS units lucky enough to escape savage beatings or

execution, there were sometimes humiliations worse than death. When

one group of survivors, after six bloody years of war, pinned on their

medals in a final act of pride, they were mobbed by US souvenir seekers

who plucked from them the last vestige of their valor.33

Rape began almost immediately and there was a viciousness in the acts as if we women were being punished for Breslau having resisted for so long. . . . Let me say that I was young, pretty, plump and fairly inexperienced. A succession of Ivans gave me over the next week or two a lifetime of experience. Luckily very few of their rapes lasted more than a minute. With many it was just a matter of seconds before they collapsed gasping. What kept me sane was that almost from the very first one I felt only a contempt for these bullying and smelly peasants who could not act gently towards a woman, and who had about as much sexual technique as a rabbit.36

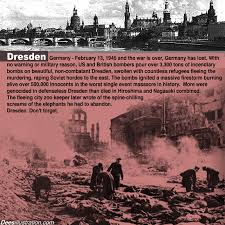

At devastated Dresden, Chemnitz and other cities that now for the first time experienced Soviet occupation, the situation was the same.

“On the morning of May 9th, the Russian troops swarmed into town,” wrote a priest from Goerlitz.

By noon, the Russians, flushed with victory, were looting all the houses and raping the womenfolk. Most of the soldiers were under the influence of drink, and as a result the number of atrocities began to increase at an alarming rate. ...

As soon as it grew dark the streets re-echoed with the screams of women and girls who had fallen into the hands of the Russians. Every ten minutes or so, parties of soldiers raided the house. As I was attired in the dress of my order, I tried to protect the occupants of the house by pointing to the cross I was wearing. . . . All went well until about three o’clock in the morning. Just as we were beginning to hope that the dreadful night was over, four drunken Russians appeared and started searching the house for two girls who had hidden in a room on the fourth floor. After ransacking our apartment, they went upstairs. . . . They found the two girls and locked the three of us in the room. I went down on my knees and begged them not to molest us. Thereupon they forced me onto a chair; one of them stood in front of me, pointing his loaded revolver at me, and made me look on whilst the others raped the poor girls. It was dreadful.37

“There were no limits to the bestiality and licentiousness of these troops . . . ,”echoed a pastor from Milzig.“Girls and women were routed out of their hiding-places, out of the ditches and thickets where they had sought shelter from the Russian soldiers, and were beaten and raped. Older women who refused to tell the Russians where the younger ones had hidden were likewise beaten and raped.”38

“Fear is always present,” young Regina Shelton added. “It flares into panic at tales of atrocities—mutilated nude bodies tossed by the wayside—a woman nailed spread-eagle to a cart and gang-raped while bleeding to death from her wounds—horrible diseases spread to their victims by sex-drunken Mongolians.”39

“Is this the peace we yearned for so long?” cried Elsbeth Losch from a town near Dresden. “When will all this have an end?”40

Crowds of Czechs awaited the transports of German prisoners in the streets to pelt them with stones, spit into their faces, and beat them with any object that came to hand. German women, children, and men ran the gauntlet, with arms over their heads, to reach the prison gates under a hail of blows and kicks. Women of every age were dragged from the groups, their heads were shaved, their faces smeared with paint, and swastikas were drawn on their bared backs and breasts. Many were violated, others forced to open their mouth to the spittle of their torturers.42

On May 9, with the fighting ended, the mob turned its attention to the thousands of Germans locked in prisons. “Several trucks loaded with German wounded and medical personnel drove into the prison court,”Thorwald continues.“The wounded, the nurses, the doctors had just climbed from their vehicles when suddenly a band of insurgents appeared from the street and pounced upon them. They tore away their crutches, canes, and bandages, knocked them to the ground, and with clubs, poles, and hammers hit them until the Germans lay still.”43

“So began a day as evil as any known to history,” muttered Thorwald.

In the street, crowds were waiting for those who were marched out of their prisons. . . .They had come equipped with everything their aroused passions might desire, from hot pitch to garden shears. . . . They . . . grabbed Germans—and not only SS men—drenched them with gasoline, strung them up with their feet uppermost, set them on fire, and watched their agony, prolonged by the fact that in their position the rising heat and smoke did not suffocate them. They . . . tied German men and women together with barbed wire, shot into the bundles, and rolled them down into the Moldau River. . . . They beat every German until he lay still on the ground, forced naked women to remove the barricades, cut the tendons of their heels, and laughed at their writhing. Others they kicked to death.44

“At the corner opening onto Wasser Street,” said Czech, Ludek Pachmann,“hung three naked corpses, mutilated beyond recognition, their teeth entirely knocked out, their mouths nothing but bloody holes. Others had to drag their dead fellow-Germans into Stefans Street.... ‘Those are your brothers, kiss them!’ And so the still-living Germans, lips pressed tightly together, had to kiss their dead.”45

As he tried to escape the city, Gert Rainer, a German soldier disguised as a priest, saw sights that seemed straight from hell:

A sobbing young woman was kneeling, showering kisses on a child in her arms. . . . The child’s eyes had been gouged out, and a knife still protruded from his abdomen. The woman’s torn clothing and disheveled hair indicated that she had fought like a fury. Lost in her sorrow, she had not noticed the approaching stranger. He bent down to her and put her in mind that she had better not stay here. She was in danger of being shot herself.

“But that’s what I want!” she suddenly cried.“I don’t want to go on living without my little Peter!”

In their sadistic ecstasy, people turned public mass murder into a folk festival. . . . Five young women had been tied to an advertising pillar, the rope wrapped about them several times. Their seven children had been packed into a gutter of sorts at their feet. . . .A Czech woman, perhaps 50 years of age, was pouring gasoline over the tied-up mothers. Others were spitting in their faces, slapping them and tearing whole fistfuls of hair. Then the oldest of them, laughing frenetically, lit a newspaper and ran around the pillar holding the burning paper to the gasoline-soaked victims. Like a flash, the pillar and the five others disappeared in flames several meters high. . . . The spectators had not noticed that one of the burning Germans had torn through the charring rope and thrown herself into the flames that licked up through the grating.With strength borne of a courage beyond death, she lifted out the grating and, lying on her stomach, tried to reach down into the tangle of blazing children. Lifeless, she lay in the flames.

In the meantime, the other four women, on fire from their feet to their hair, had slumped down as the common support of the rope was gone. That was the cue for their murderers to begin dancing around the pillar, cheering and rejoicing. The howling of the butchers grew even louder.

On Wenzels Square there was not one lamp-post without a German soldier strung up from it. The majority of them had been war-injured. . . . A crowd literally jumping for joy surrounded an arena-like clearing, in the center of which two men held a stark-naked young German woman. Each of her breasts had been pierced with a large safety-pin, from which Iron Crosses were hung. A rod bearing a swastika flag at one end had been stabbed through her navel.... A naked German lay motionless beside her trampled child. She had been beaten to death. A gaping head wound revealed her brain, oozing out.

Several men had been dragged down from a Wehrmacht truck. Their hands were tied, the other end of the rope fastened to the hitch beneath the back end of the truck. . . . A young Czech climbed into the driver’s seat. When the truck started, the spectators fell into a frenzy of hatred. . . . The five captives were pulled along by ropes some 60 feet long. As yet they could keep up with the truck. But the more the driver picked up speed, the more it became impossible for them to keep on their feet. One after the other fell, jerked forward, and was dragged along at ever-increasing speed. After but a few rounds, the Germans were mangled beyond recognition. One single lump of blood, flesh and dirt comprised the pitiful haul of this chariot of bestiality.46

At the huge sports stadium, thousands of Germans were herded onto the field to provide amusement for a laughing, howling audience. “Before our very eyes . . . they were tortured to death in every conceivable way,” remembered Josefine Waimann. “Most deeply branded on my memory is the pregnant woman whose belly . . . uniformed Czechs slashed open, ripped out the fetus and then, howling with glee, stuffed a dachshund into the torn womb of the woman, who was screaming dreadfully. . . . The slaughter happening in the arena before our very eyes was like that in ancient Rome.”47

The horror born at Prague soon spread to the rest of Czechoslovakia, particularly the Sudetenland, where Germans had lived for over

seven centuries.

The horror born at Prague soon spread to the rest of Czechoslovakia, particularly the Sudetenland, where Germans had lived for over

seven centuries.

“Take everything from the Germans,” demanded Czech president, Edvard Benes, “leave them only a handkerchief to sob into!”48

“You may kill Germans, it’s no sin,” cried a priest to a village mob.49 At Bilna, wrote a chronicler,

men and women were rounded up in the market square, had to strip naked and were made to walk single-file while being beaten by the population with whips and canes. Then . . . the men had to crawl on all fours, like dogs, one behind the other, during which they were beaten until they lost control of their bowels; each had to lick the excrement off the one in front of him. This torture continued until many of them had been beaten to death....What was done to the women there simply cannot be described, the sadistic monstrousness of it is simply too great for words.50

“When I passed through Czechoslovakia after the collapse,” one German soldier recalled, “I saw severed human heads lining window sills, and in one butcher’s shop naked corpses were hanging from the meat hooks.”51

When the fury had finally spent itself in Czechoslovakia, over 200,000

people had been butchered. Similar purges of German minorities

occurred in Romania, Hungary and Yugoslavia where men, women

and children, by the hundreds of thousands, were massacred in cold

blood. The slaughter throughout Europe was not confined to ethnic

Germans alone. Following the Allied occupation of France, over

100,000 French citizens were murdered by their countrymen because

of collaboration with the Germans or anti-communist activities. Similar,

though smaller, reckonings took place in Belgium, Holland, Denmark,

and Norway.

When the fury had finally spent itself in Czechoslovakia, over 200,000

people had been butchered. Similar purges of German minorities

occurred in Romania, Hungary and Yugoslavia where men, women

and children, by the hundreds of thousands, were massacred in cold

blood. The slaughter throughout Europe was not confined to ethnic

Germans alone. Following the Allied occupation of France, over

100,000 French citizens were murdered by their countrymen because

of collaboration with the Germans or anti-communist activities. Similar,

though smaller, reckonings took place in Belgium, Holland, Denmark,

and Norway.

Since Soviet soldiers captured or surrendering in German uniform were guaranteed protection under the Geneva Convention, most Russian prisoners felt certain they were beyond Stalin’s grasp; that the Western democracies, founded on freedom, liberty and law, would honor the treaty and protect them.54 Although many British and American soldiers initially despised their Russian captives, both for being an enemy, as well as “traitors” to their country, attitudes among many began to soften upon closer examination.

“When the screening began, I had little sympathy for these Russians in their battered German uniforms . . . ,” wrote William Sloane Coffin, Jr., who acted as translator for several colonels who interrogated the prisoners. “But as the colonels, eager to establish their cover and satisfy their curiosity, encouraged the Russians to tell their personal histories, I began to understand the dilemma the men had faced.”55

They spoke not only of the cruelties of collectivization in the thirties but of arrests, shootings and wholesale deportations of families. Many of the men themselves had spent time in Soviet jails. . . . Soon my own interest was so aroused that I began to spend evenings in the camp hearing more and more tales of arrest and torture. . . . Hearing . . . the personal histories of those who had joined Vlasov’s army made me increasingly uncomfortable with the words “traitor” and “deserter,” as applied to these men. Maybe Stalin’s regime was worthy of desertion and betrayal?56

Added a Russian prisoner, one of thousands captured by the Germans who joined Vlasov rather than starve in a POW camp:

You think, Captain, that we sold ourselves to the Germans for a piece of bread? Tell me, why did the Soviet Government forsake us? Why did it forsake millions of prisoners? We saw prisoners of all nationalities, and they were taken care of. Through the Red Cross they received parcels and letters from home; only the Russians received nothing. In Kassel I saw American Negro prisoners, and they shared their cakes and chocolates with us. Then why didn’t the Soviet Government, which we considered our own, send us at least some plain hardtack? . . . Hadn’t we fought? Hadn’t we defended the Government? Hadn’t we fought for our country? If Stalin refused to have anything to do with us, we didn’t want to have anything to do with Stalin!57

“I lost, so I remain a traitor . . . ,” conceded Vlasov himself, who, though he might easily have saved himself, chose instead to share the fate of his men. As the Russian general reminded his captors, however, if he was a traitor for seeking foreign aid to liberate his country, then so in their own day were George Washington and Benjamin Franklin.58

Despite the Geneva Convention, despite the strong likelihood that returnees would be massacred, Gen. Eisenhower and other top leaders were determined that Russian repatriation would be carried out to the letter. Terrible portents of what lay ahead had come even before the war was over.

When the British government prepared to return from England thousands of Soviets in the winter of 1944/45, many prisoners attempted suicide or tried to escape. Once the wretched cargo was finally forced onto ships, heavy guards were posted to prevent the prisoners from leaping overboard. Upon reaching Russian ports, few British seamen could doubt the fate of their charges once they were marched out of sight by the NKVD, or secret police. At Odessa on the Black Sea, noisy bombers soon appeared and circled tightly over the docks while loud sawmills joined the chorus to drown the sounds of screams and gunfire echoing from the warehouses. Within half an hour, the airplanes flew away, the sawmills shut down, and all was quiet again.59 A similar scenario was played out when four thousand Soviets were forcibly repatriated from the United States.60

To prevent Russian riots in Europe when the war was over, Allied authorities kept the operations top secret, with only a minimum of officers privy to the moves. Additionally, rumors and counter-rumors were planted, stating that the prisoners would be transferred to cleaner camps soon or even set free.61 Not all Americans had the stomach for it. As a translator, William Sloane Coffin, Jr. had not only grown to like and respect the men, but empathize with their plight. On the night before the surprise repatriation from the camp at Plattling, the Russians staged a theatrical performance in honor of several US interrogators. Sickened by their own treachery, the officers spent the night drinking and ordered Coffin to fill in for them instead.62

For a while I thought I was going to be physically ill. Several times I turned to the [Russian] commandant sitting next to me. It would have been easy to tip him off. There was still time. The camp was minimally guarded. Once outside the men could tear up their identity cards, get other clothes. . . . Yet I couldn’t bring myself to do it. It was not that I was afraid of being court-martialed.... But I too had my orders. . . . The closest I came was at the door when the commandant said good night. . . . I almost blurted out . . . “Get out and quick.” But I didn’t. Instead I drove off cursing the commandant for being so trusting.63

In the predawn darkness the following day, as tanks and searchlights surrounded the camp, hundreds of US soldiers moved in. Surprised though they were, some Russians acted swiftly.

“Despite the fact that there were three GIs to every Russian,” Coffin noted,“I saw several men commit suicide. Two rammed their heads through windows sawing their necks on the broken glass until they cut their jugular veins. Another took his leather boot-straps, tied a loop to the top of his triple-decker bunk, put his head through the noose and did a back flip over the edge which broke his neck.”64

With clubs swinging, troops ruthlessly drove the startled survivors into waiting trucks which were soon speeding toward the Soviet lines.65

“We stood over them with guns and our orders were to shoot to kill if they tried to escape from our convoy,” said an American officer in one group.“Needless to say many of them did risk death to effect their escape.”66

Much like the British and American sailors who had delivered a living cargo to its executioner, Allied soldiers knew very well the journey was a one-way trip. “We . . . understood they were going to their deaths. Of this, there was never any doubt whatsoever,” a British Tommy admitted. “It was that night and the following day that we started to count the small-arms fire coming from the Russian sector to the accompaniment of the finest male voice choir I have ever heard. The voices echoed round and round the countryside. Then the gunfire would be followed by a huge cheer.”67

In much the same way as above were the rest of Vlasov’s Russian Liberation Army forced from the camps in Germany and Austria and handed to Stalin. Many, maybe most, were dead within days of delivery. “When we captured them, we shot them as soon as the first intelligible Russian word came from their mouths,” said Captain Alexander Solzhenitsyn.68

Another group of “traitors” Stalin was eager to have repatriated were the Cossacks. Long known for its courage and fierce independence, the colorful nation fled Russia and years of communist persecution when the German Army began its withdrawal west.69 Recorded an Allied soldier:

As an army they presented an amazing sight. Their basic uniform was German, but with their fur Cossack caps, their mournful dundreary whiskers, their knee high riding boots, and their roughly-made horse-drawn carts bearing all their worldly goods and chattels, including wife and family, there could be no mistaking them for anything but Russians. They were a tableau from the Russia of 1812. Cossacks are famed as horsemen and these lived up to their reputation.70

Like the Americans who returned Vlasov’s army, the British were eager to appease Stalin by handing back the hapless Cossacks. Unlike the Americans though, the British realized that by separating the thirty thousand followers from their leaders would make the transfers simpler. When the elders were requested to attend a “conference” on their relocation elsewhere in Europe, they complied. Honest and unsophisticated—many having served in the old Imperial Army—the Cossack officers were easily deceived.71

“On the honor of a British officer . . . ,” assured the English when the people asked about their leaders. “They’ll all be back this evening. The officers are only going to a conference.”72

With the beheading of the Cossack Nation, the job of repatriating the rest was made easier, but not easy. When the men, women and children at the various Cossack camps refused to enter the trucks and go willingly to their slaughter, Tommies, armed with rifles, bayonets and pick handles, marched in.“we prefer death than to be returned to the Soviet Union . . . ,” read signs printed in crude English.“We, husbands, mothers, brothers, sisters, and children pray for our salvation!!!”73

Wrote one British officer from the Cossack camp at Lienz, Austria:

As soon as the platoon approached to commence loading, the people formed themselves into a solid mass, kneeling and crouching with their arms locked around each others’ bodies. As individuals on the outskirts of the group were pulled away, the remainder compressed themselves into a still tighter body, and as panic gripped them they started clambering over each other in frantic efforts to get away from the soldiers. The result was a pyramid of hysterical, screaming human beings, under which a number of people were trapped. The soldiers made frantic efforts to split this mass in order to try to save the lives of these persons pinned underneath, and pickhelves and rifle butts were used on arms and legs to force individuals to loosen their hold. When we eventually cleared this group, we discovered that one man and one woman had suffocated. Every person of this group had to be forcibly carried onto the trucks.74

When one huddled mob was beaten into submission, the troops waded into another. Recalled a Cossack mother as the Tommies cut and clubbed their way forward:

There was a great crush; I found myself standing on someone’s body, and could only struggle not to tread on his face. The soldiers grabbed people one by one and hurried them to the lorries, which now set off half-full. From all sides in the crowd could be heard cries: “Avaunt thee, Satan! Christ is risen! Lord have mercy upon us!”

Those that they caught struggled desperately and were battered. I saw how an English soldier snatched a child from its mother and wanted to throw him into the lorry. The mother caught hold of the child’s leg, and they each pulled in opposite directions. Afterwards I saw that the mother was no longer holding the child and that the child had been dashed against the side of the lorry.75

As in the case above, soldiers tried first to wrench children from their

mothers’ arms for once a child had been hurled into a truck the parents

were sure to follow. In the tumult, some victims managed to break

free and run. Most were mowed down by machine-guns. Those not

hit drowned themselves in the nearby river or cut the throats of their

entire family. In the Lienz operation alone, as many as seven hundred

men, women and children committed suicide or were cut down

by bullets and bayonets.76

As in the case above, soldiers tried first to wrench children from their

mothers’ arms for once a child had been hurled into a truck the parents

were sure to follow. In the tumult, some victims managed to break

free and run. Most were mowed down by machine-guns. Those not

hit drowned themselves in the nearby river or cut the throats of their

entire family. In the Lienz operation alone, as many as seven hundred

men, women and children committed suicide or were cut down

by bullets and bayonets.76

Eventually, the entire Cossack nation had been delivered to the Soviets. Within days, most were either dead or bolted into cattle cars for the one-way ride to Siberia.77

Certainly, not every British or American officer had a heart for the repatriations, known broadly—and aptly—as “Operation Keelhaul.” Some actually placed their careers on the line. When Alex Wilkinson was ordered to turn over Russians in his district to the Soviets, the British colonel replied: “Only if they are willing to go.”

It was then suggested to me that they should be collected and put into the trains whether they liked it or not. I then asked how they were to be put into the trains? And I was told that a few machine-guns might make them change their minds. To which I replied “that will not happen while I am here.78

When Wilkinson agreed to obey orders “on the one condition that the trains go west not east,” his commander was furious.

“Within a fortnight of that meeting,” said the Colonel,“I was relieved of my command and sent back to England with a report that ‘I lacked drive.’”79

Another British officer who “lacked drive” was Sir Harold Alexander. “To compel . . . repatriation,” the field marshal wrote his government from Italy, “would certainly either involve the use of force or drive them into committing suicide. . . . Such treatment, coupled with the knowledge that these unfortunate individuals are being sent to an almost certain death, is quite out of keeping with the traditions of democracy and justice, as we know them.”80

Unfortunately, such courageous acts had little impact on the removals. Alexander, like Wilkinson, was soon sent elsewhere and officers less inclined to cause trouble took their place. Nevertheless, word of what was occurring did trickle out, forcing top Allied officials to issue denials.

“It is not and has not been the policy of the US and British Government [sic] involuntarily to repatriate any Russian . . . ,” assured a spokesman for Supreme Allied Command.81

“No instances of coercion have been brought to our attention . . . ,” echoed US Secretary of State George C. Marshall.“It is against American tradition for us to compel these persons, who are now under our authority, to return against their will.”82

With what little public concern there was allayed by such announcements, the Allies worked feverishly to fulfill their pact with Stalin.“We ought to get rid of them all as soon as possible,” wrote an impatient Winston Churchill.83

Another category of Russians the Allies repatriated were the POWs in German hands. Because of Stalin’s well known equation of capture or surrender on the battlefield with treason, few of these starved, diseased and ragged Red Army veterans were eager to return where, at best, a slow, agonizing death in Siberia awaited. And even for those stalwart patriots who steadfastly refused to collaborate with the Germans and remained in their prison camps, where they ate tree bark, grass, and their dead comrades, a “tenner”—or ten years in Siberia— was almost mandatory.84 When a curious Russian guard queried one such repatriate what he had done to deserve a twenty-five year sentence, the hapless prisoner replied, “Nothing at all.”

“You’re lying,” the guard laughed, “the sentence for ‘nothing at all’ is ten years.”85

Yet another group on the seemingly endless list Stalin wanted returned were Soviet slave laborers. Again, the Allies made haste to comply.

“We had to go round the farms to collect the Russians who had been working as laborers on the farms,” one British lieutenant remembered. “They were mostly old men and women, and we were amazed and somewhat perplexed to have people who had literally been slaves on German farms, falling on their knees in front of you and begging to be allowed to stay, and crying bitterly—not with joy—when they were told they were being sent back to Russia.”86

“It very quickly became apparent,” added another English officer, “that 99% of these people did not wish to return to the Motherland,because (a) they feared the Communist Party and the life they had lived in Soviet Russia and (b) life as slave-laborers in Nazi Germany had been better than life in Russia.”87

Because of their exposure to the West with its freedoms and high standard of living, Stalin rightly feared the “contaminating” influence these slaves might have on communism at home and abroad if allowed to remain.

Another body of Russians Stalin demanded the return of were the emigres, or those “whites” who had fought the Bolsheviks in 1917 and fled to the West upon defeat. Included in the number were individuals who had been mere children at the time of the revolution. Indeed, so willing were the Allies to comply with Stalin’s every demand, that Soviet authorities were themselves surprised at how easily this latter group of “traitors” were delivered to the executioner.88

The roundups and repatriations continued across Europe until eventually over five million Soviet citizens had been delivered to death, torture and slavery.89 However, if the Allies expected to enamor Stalin by their actions, they were mistaken. In fact, quite the opposite occurred. Rightly regarding the repatriations as a Western betrayal of its natural allies, the Red dictator and other Soviet leaders viewed the entire program as proof of American and British moral decay and a blatant, “groveling” attempt at appeasement.90

Curiously, it was Liechtenstein, one of the tiniest nations in Europe, that Stalin had most respect for, for it was Liechtenstein—a country with no army and a police force of only eleven men—that had the moral integrity to do what others did not dare. When the communists angrily demanded the return of all Soviet citizens within the little nation’s boundaries for “crimes against the Motherland,” Prince Franz Joseph II politely but firmly requested proof. When none was forthcoming, the Soviets quietly dropped the matter. Remembered an interviewer:“I asked the Prince if he had not had misgivings or fears as to the success of this policy at the time. He seemed quite surprised at my question.‘Oh no,’ he explained,‘if you talk toughly with the Soviets they are quite happy. That, after all, is the language they understand.’”91

When the camps were finally cleared and the dark deed was done, many soldiers who had participated wanted nothing more than to forget the entire episode. Most found, however, that they could not.

“My part in the . . . operation left me a burden of guilt I am sure to carry the rest of my life,” confessed William Sloane Coffin, Jr.92

“The cries of these men, their attempts to escape, even to kill themselves rather than be returned to the Soviet Union . . . still plague my memory,” echoed Brigadier General Frank L. Howley.93

“It just wasn’t human,” an American GI said simply.94

Well aware that some grim details from Operation Keelhaul were bound to surface, Allied leaders were quick to squash rumors and reassure the public.“The United States Government has taken a firm stand against any forced repatriation and will continue to maintain this position . . . ,” said a spokesman for the War Department long after most of the Russian returnees were either dead or enslaved. “There is no intention that any refugee be returned home against his will.”95 To do otherwise, General Eisenhower later chimed,“would ...violate the fundamental humanitarian principles we espoused.”96 [

Even as he was soothing public concern over Russian repatriation,

Eisenhower’s “humanitarian principles” were at work in the numerous

American concentration camps.

Even as he was soothing public concern over Russian repatriation,

Eisenhower’s “humanitarian principles” were at work in the numerous

American concentration camps.

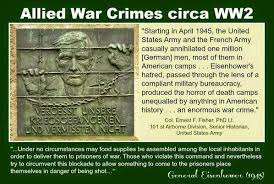

“God, I hate the Germans,” Eisenhower had written his wife in 1944. 97 As Mrs. Eisenhower and anyone else close to the general knew, Dwight David Eisenhower’s loathing of all things German was nothing short of pathological.

With the final capitulation on May 8, the supreme allied commander found himself in control of over five million ragged, weary, but living, enemy soldiers.98 “It is a pity we could not have killed more,” muttered the general, dissatisfied with the body-count of the greatest bloodbath in world history.99 And so, the Allied commander settled for next best: If he could not kill armed Germans in war, he would kill disarmed Germans in peace. Because the Geneva Convention guaranteed POWs of signer nations the same food, shelter and medical attention as their captors, and because these laws were to be enforced by the International Red Cross, Eisenhower simply circumvented the treaty by creating his own category for prisoners. Under the general’s reclassification, German soldiers were no longer considered POWs, but DEFs— Disarmed Enemy Forces. With this sleight-of-hand, and in direct violation of the Geneva Convention, Eisenhower could now deal in secret with those in his power, free from the prying eyes of the outside world.100

Even before war’s end, thousands of German POWs had died in American captivity from starvation, neglect and, in many cases, outright murder. Wrote a survivor from one camp in April 1945:

Each group of ten was given the outdoor space of a medium-sized living room. We had to live like this for three months, no roof over our heads. Even the badly wounded only got a bundle of straw. And it rained on the Rhine. For days. And we were always in the open. People died like flies. Then we got our first rations. . . We got one slice of bread for ten men. Each man got a tiny strip of that one slice. . . . And this went on for three long months. I only weighed 90 pounds. The dead were carried out every day. Then a voice would come over the loudspeaker: “German soldiers, eat slowly. You haven’t had anything to eat in a long time. When you get your rations today from the best fed army in the world, you’ll die if you don’t eat slowly.”101

When two members of the US Army Medical Corp stumbled upon one of Eisenhower’s camps, they were horrified by what they saw:

Huddled close together for warmth, behind the barbed wire was a most awesome sight—nearly 100,000 haggard, apathetic, dirty, gaunt, blank-staring men clad in dirty field gray uniforms, and standing ankle-deep in mud.... The German Division Commander reported that the men had not eaten for at least two days, and the provision of water was a major problem—yet only 200 yards away was the River Rhine running bankfull.102

-1.jpg) With German surrender and the threat of retaliation against Allied

POWs entirely erased, deaths in the American concentration camps

accelerated dramatically. While tens of thousands died of starvation

and thirst, hundreds of thousands more perished from overcrowding

and disease. Said sixteen-year-old Hugo Stehkamper:

With German surrender and the threat of retaliation against Allied

POWs entirely erased, deaths in the American concentration camps

accelerated dramatically. While tens of thousands died of starvation

and thirst, hundreds of thousands more perished from overcrowding

and disease. Said sixteen-year-old Hugo Stehkamper:

I only had a sweater to protect me from the pouring rain and the cold. There just wasn’t any shelter to be had. You stood there, wet through and through, in fields that couldn’t be called fields anymore—they were ruined. You had to make an effort when you walked to even pull your shoes out of the mud. . . .

It’s incomprehensible to me how we could stand for many, many days without sitting, without lying down, just standing there, totally soaked. During the day we marched around, huddled together to try to warm each other a bit. At night we stood because we couldn’t walk and tried to keep awake by singing or humming songs. Again and again someone got so tired his knees got weak and he collapsed.103

Added a starving comrade from a camp near Remagen:

The latrines were just logs flung over ditches next to the barbed wire fences. To sleep, all we could do was to dig out a hole in the ground with our hands, then cling together in the hole....Because of illness, the men had to defecate on the ground. Soon, many of us were too weak to take off our trousers first. So our clothing was infected, and so was the mud where we had to walk and sit and lie down. There was no water at all at first, except the rain....

We had to walk along between the holes of the soft earth thrown up by the digging, so it was easy to fall into a hole, but hard to climb out. The rain was almost constant along that part of the Rhine that spring. More than half the days we had rain. More than half the days we had no food at all. On the rest, we got a little K ration. I could see from the package that they were giving us one tenth of the rations that they issued to their own men. . . . I complained to the American camp commander that he was breaking the Geneva Convention, but he just said, “Forget the Convention. You haven’t any rights.”

Within a few days, some of the men who had gone healthy into the camps were dead. I saw our men dragging many dead bodies to the gate of the camp, where they were thrown loose on top of each other onto trucks, which took them away.104

“The Americans were really shitty to us,” a survivor at another camp

recalled.“All we had to eat was grass.”105 At Hans Woltersdorf’s prison,

the inmates survived on a daily soup made of birdseed. Not fit for

human consumption, read the words on the sacks.106 At another camp,

a weeping seventeen-year-old stood day-in, day-out beside the barbed

wire fence. In the distance, the youth could just view his own village.

One morning, inmates awoke to find the boy dead, his body strung up

by guards and left dangling on the wires. When outraged prisoners

cried “Murderers! Murderers!” the camp commander withheld their

meager rations for three days. “For us who were already starving and

could hardly move because of weakness . . . it meant death,” said one

of the men.107

“The Americans were really shitty to us,” a survivor at another camp

recalled.“All we had to eat was grass.”105 At Hans Woltersdorf’s prison,

the inmates survived on a daily soup made of birdseed. Not fit for

human consumption, read the words on the sacks.106 At another camp,

a weeping seventeen-year-old stood day-in, day-out beside the barbed

wire fence. In the distance, the youth could just view his own village.

One morning, inmates awoke to find the boy dead, his body strung up

by guards and left dangling on the wires. When outraged prisoners

cried “Murderers! Murderers!” the camp commander withheld their

meager rations for three days. “For us who were already starving and

could hardly move because of weakness . . . it meant death,” said one

of the men.107

“Civilians from nearby villages and towns were prevented at gunpoint from passing food through the fence to prisoners,” revealed another German from his camp near Ludwigshafen.108

There was no lack of food or shelter among the victorious Allies. Indeed, American supply depots were bursting at the seams. “More stocks than we can ever use,” one general announced. “They stretch as far as the eye can see.” Instead of allowing even a trickle of this bounty to reach the compounds, the starvation diet was further reduced. “Outside the camp the Americans were burning food which they could not eat themselves,” said a starving Werner Laska from his prison.109

Horrified by the silent, secret massacre, the International Red

Cross—which had over 100,000 tons of food stored in Switzerland—tried to intercede. When two trains loaded with supplies reached the

camps, however, they were turned back by American officers.110

Horrified by the silent, secret massacre, the International Red

Cross—which had over 100,000 tons of food stored in Switzerland—tried to intercede. When two trains loaded with supplies reached the

camps, however, they were turned back by American officers.110

“These Nazis are getting a dose of their own medicine,” a prison commandant reported proudly to one of Eisenhower’s political advisors.111

“German soldiers were not common law convicts,” protested a Red Cross official, “they were drafted to fight in a national army on patriotic grounds and could not refuse military service any more than the Americans could.”112

Like this individual, many others found no justification whatsoever in the massacre of helpless prisoners, especially since the German government had lived up to the Geneva Convention, as one American put it, “to a tee.”

“I have come up against few instances where Germans have not treated prisoners according to the rules, and respected the Red Cross,” wrote war correspondent Allan Wood of the London Express. 113

“The Germans even in their greatest moments of despair obeyed the Convention in most respects,” a US officer added. “True it is that there were front line atrocities—passions run high up there—but they were incidents, not practices; and maladministration of their American prison camps was very uncommon.”114

Nevertheless, despite the Red Cross report that ninety-nine percent of American prisoners of war in Germany have survived and were on their way home, Eisenhower’s murderous program continued apace.115 One officer who refused to have a hand in the crime and who began releasing large numbers of prisoners soon after they were disarmed was George Patton.116 Explained the general:

I emphasized to the troops the necessity for the proper treatment of prisoners of war, both as to their lives and property. My usual statement was . . . “Kill all the Germans you can but do not put them up against a wall and kill them. Do your killing while they are still fighting. After a man has surrendered, he should be treated exactly in accordance with the Rules of Land Warfare, and just as you would hope to be treated if you were foolish enough to surrender. Americans do not kick people in the teeth after they are down.”117

Although other upright generals such as Omar Bradley and J. C. H. Lee issued orders to release POWs, Eisenhower quickly overruled them. Mercifully, for the two million Germans under British control, Bernard Montgomery refused to participate in the massacre. Indeed, soon after war’s end, the field marshal released and sent most of his prisoners home.118

After being shuttled from one enclosure to the next, Corporal Helmut Liebich had seen for himself all the horrors the American death camps had to give. At one compound, amused guards formed lines and beat starving prisoners with clubs and sticks as they ran the gauntlet for their paltry rations. At another camp of 5,200 men, Liebich watched as ten to thirty bodies were hauled away every day. At yet another prison, there was “35 days of starvation and 15 days of no food at all,” and what little the wretched inmates did receive was rotten. Finally, in June 1945, Liebich’s camp at Rheinberg passed to British control. Immediately, survivors were given food and shelter and for those like Liebich—who now weighed 97 pounds and was dying of dysentery—swift medical attention was provided.119

“It was wonderful to be under a roof in a real bed,” the corporal reminisced. “We were treated like human beings again. The Tommies treated us like comrades.”120

Before the British could take complete control of the camp, however, Liebich noted that American bulldozers leveled one section of the compound where skeletal—but breathing—men still lay in their holes.121

“Gee! I hope we don’t ever lose a war,” muttered one GI as he stared at the broken, starving wrecks being selected for slavery.123

“When we marched through Namur in a column seven abreast, there was also a Catholic procession going through the street,” remembered one slave as he moved through Belgium. “When the people saw the POWs, the procession dissolved, and they threw rocks and horse shit at us. From Namur, we went by train in open railroad cars. At one point we went under a bridge, and railroad ties were thrown from it into the cars filled with POWs, causing several deaths. Later we went under another overpass, and women lifted their skirts and relieved themselves on us.”124

Once in France, the assaults intensified. “We were cursed, spat upon and even physically attacked by the French population, especially the women,” Hans von der Heide wrote.“I bitterly recalled scenes from the spring of 1943, when we marched American POWs through the streets of Paris. They were threatened and insulted no differently by the French mob.”125

Like the Americans, the French starved their prisoners. Unlike the Americans, the French drained the last ounce of labor from their victims before they dropped dead. “I have seen them beaten with rifle butts and kicked with feet in the streets of the town because they broke down of overwork,” remarked a witness from Langres.“Two or three of them die of exhaustion every week.”126

“In another camp,” a horrified viewer added,“prisoners receive only one meal a day but are expected to continue working. Elsewhere so many have died recently that the cemetery space was exhausted and another had to be built.”127

Revealed the French journal, Figaro: “In certain camps for German prisoners of war . . . living skeletons may be seen . . . and deaths from undernourishment are numerous. We learn that prisoners have been savagely and systematically beaten and that some have been employed in removing mines without protection equipment so that they have been condemned to die sooner or later.”128

“Twenty-five percent of the men in our camp died in one month,” echoed a slave from Buglose.129

The enslavement of German soldiers was not limited to France. Although fed and treated infinitely better, several hundred thousand POWs in Great Britain were transformed into virtual slaves. Wrote historian Ralph Franklin Keeling at the time:

The British Government nets over $250,000,000 annually from its slaves. The Government, which frankly calls itself the “owner” of the prisoners, hires the men out to any employer needing men, charging the going rates of pay for such work—usually $15 to $20 per week. It pays the slaves from 10 cents to 20 cents a day . . . plus such “amenities” as slaves customarily received in the former days of slavery in the form of clothing, food, and shelter.130

When prisoners were put to work raising projects for Britain’s grand “Victory in Europe” celebration, one English foreman felt compelled to quip:“I guess the Jerries are preparing to celebrate their own downfall. It does seem as though that is laying it on a bit thick.”131

In vain did the International Red Cross protest:

The United States, Britain, and France . . . are violating International Red Cross agreements they solemnly signed in 1929. Investigation at Geneva headquarters today disclosed that the transfer of German war prisoners captured by the American army to French and British authorities for forced labor is nowhere permitted in the statues of the International Red Cross, which is the highest authority on the subject in the world.132

“Others,” observed American guard, Martin Brech,“tried to escape in a demented or suicidal fashion, running through open fields in broad daylight towards the Rhine to quench their thirst. They were mowed down.”134

As if their plight were not already hideous enough, prisoners occasionally became the targets of drunken and sadistic guards who sprayed the camps with machine-gun fire for sport.135 “I think . . ,” Private Brech continued,“that soldiers not exposed to combat were trying to prove how tough they were by taking it out on the prisoners and civilians.”

I encountered a captain on a hill above the Rhine shooting down at a group of German civilian women with his .45 caliber pistol. When I asked, “Why?” he mumbled,“Target practice,” and fired until his pistol was empty. . . . This is when I realized I was dealing with cold-blooded killers filled with moralistic hatred.136

While continuing to deny the Red Cross and other relief agencies access to the camps, Eisenhower stressed among his lieutenants the need for secrecy. “Ike made the sensational statement that . . . now that hostilities were over, the important thing was to stay in with world public opinion—apparently whether it was right or wrong . . . ,” recorded George Patton. “After lunch [he] talked to us very confidentially on the necessity for solidarity in the event that any of us are called before a Congressional Committee.”137

To prevent the gruesome details from reaching the outside world— and sidetrack those that did—counter-rumors were circulated stating that, far from mistreating and murdering prisoners, US camp commanders were actually turning back released Germans who tried to slip back in for food and shelter.138

Ultimately, at least 800,000 German prisoners died in the American and French death camps.“Quite probably,” one expert later wrote, the figure of one million is closer to the mark. And thus, in “peace,” did ten times the number of Landsers die than were killed on the whole Western Front during the whole of the war.139

Unlike their democratic counterparts, the Soviet Union made little effort to hide from the world the fate of German prisoners in its hands. Toiling by the hundreds of thousands in the forests and mines of Siberia, the captives were slaves pure and simple and no attempt was made to disguise the fact. For the enslaved Germans, male and female, the odds of surviving the Soviet gulags were even worse than escaping the American or French death camps and a trip to Siberia was tantamount to a death sentence. What little food the slaves received was intended merely to maintain their strength so that the last drop of energy could be drained from them.

And so, with the once mighty Wehrmacht now disarmed and enslaved, and with their leaders either dead or awaiting trial for war crimes, the old men, women and children who remained in the dismembered Reich found themselves utterly at the mercy of the victors. Unfortunately for these survivors, never in the history of the world was mercy in shorter supply.

next

9 A War without End

289s

Notes

Chapter 8

1. Schultz-Naumann, Last Thirty Days, 51.

2. Thorwald, Flight in the Winter, 265.

3. LeTissier, Battle of Berlin, 212.

4. DeZayas, Nemesis at Potsdam, 71.

5. Strawson, Battle for Berlin, 157.

6. Ibid., 115–116.

7. James Bacque,“The Last Dirty Secret of World War Two,” Saturday Night 104, no. 9 (Sept.1989): 31.

8. Sajer, Forgotten Soldier, 456.

9. O’Donnell, The Bunker, 293.

10. Dobson, The Cruelest Night, 149.

11. Lucas, Last Days of the Third Reich, 205.

12. Pechel, Voices from the Third Reich, 498.

13. Toland, Last 100 Days, 371.

14. Ibid.

15. Barnouw, Germany 1945, 68.

16. Ibid.; Howard A. Buechner, Dachau (Metairie, Louisiana: Thunderbird, 1986), 32.

17. Woltersdorf, Gods of War, 124–125.

18. Buechner, Dachau, 8.

19. Ibid., 64.

20. Ibid., 75–76.

21. Ibid., 104.

22. Ibid., 86.

23. Ibid., 87.

24. Ibid., 64, 98.

25. Woltersdorf, 121–122.

26. Ibid., 123.

27. Landwehr, Charlemagne’s Legionnaires, 174–177.

28. Barnouw, Germany 1945, 67–68.

29. Sajer, Forgotten Soldier, 456–457.

30. Von Luck, Panzer Commander, 212–213.

31. Strawson, Berlin, 158.

32. Toland, 100 Days, 583.

33. Lucas, Last Days, 91.

34. Duffy, Red Storm, 152.

35. Thorwald, Flight, 279.

36. Lucas, Last Days, 69.