Hellstorm

The Death of Nazi Germany

1944–1947

by Thomas Goodrich

9

The Death of Nazi Germany

1944–1947

by Thomas Goodrich

9

A War without End

What had taken the German nation over two millennia

to build, had taken its enemies a mere six years to destroy.

When the fighting finally ended on May 8, 1945, the Great

German Reich which had been one of the most modern industrial

giants in the world lay totally, thoroughly and almost hopelessly demolished.

Germany, mused an American newsman drifting through the

rubble, resembled nothing so much as it resembled “the face of the

moon.”1 Omar Bradley agreed. After viewing for himself the blackened,

smoking wreck, the US general reassured his countrymen,“I can

tell you that Germany has been destroyed utterly and completely.”2

What Leonard Mosley found at Hanover epitomized the condition

of all German cities at war’s end. Hanover, wrote the British reporter,

was the most “sullen and desolate city that I have ever seen.”

Even from there, five miles away, the devastation was appalling. . . . Hanover

looked like a wound in the earth rather than a city. As we came nearer, I looked

for the familiar signs that I used too know, but the transformation that had been

made by bombardment seemed complete. I could not recognize anywhere; whole

streets had disappeared, and squares and gardens and brooks with them, covered

in piles of bricks and stone and mortar. . . . The city was a gigantic open

sore.3

To the shock and surprise of not only Mosley and the victorious

armies, but to the survivors as well, life actually existed among and under the seemingly sterile rock piles. Like cave-dwellers from the

Stone Age, men, women and children slept, ate, whispered, suffered,

cried, and died below the tons of jagged concrete, broken pipes and

twisted metal. As one victor who viewed Berlin recorded:

A new race of troglodytes was born, one or other of whom periodically would

bob up from nowhere at one’s feet among rank weeds and rubble. . . . After a

time those who had to live among the ruins became inured or deadened to them;

this was very noticeable, especially among the children, many of whom themselves

were little veterans without an arm, an eye, or a leg, at the age of seven

or ten or twelve. They took their disablement with amazing calm, but they

grew up fast. They had to, to survive.4

Another horrifying feature of the razed cities was the nauseating

stench that hung over them like a pall. “Everywhere,” remembered

a witness, “came the putrid smell of decaying flesh to remind the living

that thousands of bodies still remained beneath the funeral pyres

of rubble.”5

“I’d often seen it described as ‘a sweetish smell’—but I find the word

‘sweetish’ imprecise and inadequate,” a Berlin woman scratched in her

diary. “It strikes me not so much a smell as something solid, tangible,

something too thick to be inhaled. It takes one’s breath away and

repels, thrusts one back, as though with fists.”6

In their own tally of bombing casualties, the British estimated they

had killed 300,000–600,000 German civilians. That some sources from

the Dresden raid set the toll there alone at 300,000–400,000 dead would

suggest that the British figures were absurdly—and perhaps deliberately—low.7

Whatever the accurate figure, the facts are that few German

families survived the war in tact. Those who did not lose a father,

a brother, a sister, a mother—or all the above—were by far the exception

to the rule. In many towns and villages the dead quite literally

outnumbered the living. For some, the hours and days following the

final collapse was simply too much. Unwilling to live any longer in a world of death, misery and alien chaos, thousands took the ultimate

step. Wrote once-wealthy Lali Horstmann of a scenario that was

replayed over and over throughout Germany:

Wilhelm, our gardener and gamekeeper, had committed suicide by hanging himself

from a tree in the woods, having first slashed the wrist arteries of his wife

and three-year-old son, refusing to leave them behind him in a world of strife

and disorder. They had been found in time to revive them, but he himself was

stark and cold. Despite his stalwart looks, Wilhelm was a sensitive man....

Yesterday drunken soldiers had upset his treasured beehives, used his jars of preserves

as shooting targets and driven the couple and child out of the house.

He had not been able to stand the strain of these repeated scenes and now lay

on the ground covered with a blanket.8

“Thousands of bodies are hanging in the trees in the woods around

Berlin and nobody bothers to cut them down,” a German pastor noted.

“Thousands of corpses are carried into the sea by the Oder and Elbe

Rivers—one doesn’t notice it any longer.”9

For Germany, May 8,1945, became known as “The Hour Zero”—the

end of a nightmare and the beginning of a dark, uncertain future. Most

assumed, no doubt, that awful though the coming weeks and months

would be, the worst was nevertheless behind them. But these people

were wrong. The worst yet lay ahead. Though the shooting and bombing

had indeed stopped, the war against Germany continued unabated.

World War II was history’s most catastrophic and terrifying war, but

what still lay ahead would prove, as Time magazine later phrased it,

“History’s most terrifying peace.”10

☭☠☭☠☭

Although forced to the shadows by public opprobrium, the Morgenthau

Plan for Germany was never actually abandoned by Franklin Roosevelt.

Indeed, up until his death, the American president had secretly

favored the “Carthaginian” approach to the conquered Reich. When

Roosevelt’s successor, Harry Truman, met at Potsdam with Stalin and the new British prime minister, Clement Attlee, in July 1945,

most of the teeth in Morgenthau’s scheme remained on the table. With

the signature of the Big Three, the plan went into effect.11

“It is not the intention of the Allies,” stated the joint declaration, “to destroy or enslave the German people.”12

Despite such solemn pronouncements meant to mollify a watching

world, it soon became abundantly clear to the Germans themselves

that the victors came not as peace-minded “liberators,” as propagandists

were wont to declare, but as conquerors fully as vengeful, ruthless

and greedy as any who ever won a war.

The Dachau Massacre

The plundering of Germany by the Soviet Union first began when

the Red Army penetrated Prussia in 1944. With war’s end, Stalin’s

methodical looting in the Russian Occupation Zone became prodigious.

Steel mills, grain mills, lumber mills, sugar and oil refineries,

chemical plants, optical works, shoe factories, and other heavy industries

were taken apart down to the last nut and bolt and sent east to

the Soviet Union where they were reassembled. Those factories allowed

to remain in Germany were to operate solely for the benefit of Russia.

Electric and steam locomotives, their rolling stock, and even the

tracks they ran on were likewise sent east.13 While the Soviet government

pillaged on a massive scale, the common Red soldier was even

more meticulous. Wrote one woman from Silesia:

The Russians systematically cleared out everything, that was for them of value,

such as all sewing machines, pianos, grand-pianos, baths, water taps, electric

plants, beds, mattresses, carpets, etc. They destroyed what they could not take

away with them. Trucks often stood for days in the rain, with the most valuable

carpets and articles of furniture in them, until everything was completely

spoiled and ruined....

If fuel was required, then whole woods were generally felled, or window-frames

and doors were torn out of the empty houses, broken up on the spot, and immediately

used for making fire. The Russians and Poles even used the staircases and

banisters as fire-wood. In the course of time, even the roofs of houses were

removed and used for heating. . . . Empty houses, open, without windowpanes,

overgrown with weeds and filthy, rats and mice in uncanny numbers,unharvested fields, land which had been fertile, now completely overgrown with

weeds and lying fallow. Not in a single village did one see a cow, a horse or a

pig. . . . The Russians had taken everything away to the east, or used it up.14

As this woman made clear, what was not looted was destroyed. Like

millions of other refugees, Regina Shelton found her way home at

the end of the war.

We have been warned by others who have witnessed signs of Russian occupancy

to expect bedlam and to abandon our hopeless mission altogether. Thus we

expect the worst, but our idea of the worst has not prepared us sufficiently for

reality. Shocked to the point of collapse, we survey a battlefield—heaps of refuse

through which broken pieces of furniture rise like cliffs; stench gags us, almost

driving us to retreat. Ragged remnants of clothes, crushed dishes, books, pictures

torn from frames,—rubble in every room. . . . Above all, the nauseating

stench that emanates from the largest and totally wrecked living room! Spoiled

contents oozes from splintered canning jars, garbage of indefinable origin is

mixed with unmistakable human excrement, and dried stain of urine discolors

crumpled paper and rags. We wade into the dump with care and poke at

some of all but unrecognizable belongings. . . . The wardrobes with doors torn

from their hinges are empty, their contents looted or mixed in stinking heaps.15

Americans were not far behind their communist counterparts and

what was not wantonly destroyed, was pilfered as “souvenirs.”

“We ‘liberated’ German property,” winked one GI. “The Russians

simply stole it.”

Unlike its primitive Soviet ally, the United States had no need for

German plants and factories. Nevertheless, and as Ralph Franklin Keeling

points out, the Americans were far and away the “most zealous”

at destroying the Reich’s ability to recover. Continues the historian:

Although America went about the business of dismantling and dynamiting German

plants with more fervor than was at first exhibited in any other zone, our

motive was quite different from the motives of our allies. Russia is anxious to

get as much loot as possible from Germany and yet to make it produce abundantly

for Russia to help make her new five year plan successful, and ultimately

to absorb the Reich into the Soviet Union. France is ravenous for loot, has

been anxious to destroy Germany forever and to annex as much of her territory

as possible. Britain has found uses for large amounts of German booty,wants to get rid of Germany as a trade competitor, while retaining her market

for British goods. The United States has no use for German plant and equipment

as booty. . . . [but wants] to eliminate German competition in world trade.

We are willing to permit the German people to subsist on their own little plot

of land, if they can, but we are determined that they never again shall engage

in foreign commerce on an important scale.16

While the US may have spurned German plants and factories, not

so the Reich’s hoard of treasure. Billions of dollars in gold, silver and

currency, as well as priceless paintings, sculptures and other art works

were plucked from their hiding places in caves, tunnels and salt mines

and shipped across the Atlantic. Additionally, and of far greater damage

to Germany’s future, was the “mental dismantling” of the Reich.

Tons of secret documents revealing Germany’s tremendous organizational

talent in business and industry were simply stolen, not only

by the Americans, but by the French, English and British Commonwealth.

Hundreds of the greatest scientists in the world were likewise

“compelled” to immigrate by the victors. As one US Government

agency quietly admitted, “Operation Paper-Clip” was the first time

in history wherein conquerors had attempted to bleed dry the inventive

power of an entire nation.17

“The real gain in reparations of this war,” Life magazine added,

was not in factories, gold or artworks, but “in the German brains

and in the German research results.”18

☭☠☭

While the Soviet Union came up short on German scientists and technicians

simply because most had wisely fled and surrendered to the

West, Russia suffered no shortage of slave labor. Added to the millions

of native dissidents, repatriated refugees, and Wehrmacht prisoners

toiling in the gulags, were millions of German civilians snatched

from the Reich. As was commonly the case, those who were to spend

years in slavery were given mere minutes to make ready. In cities, towns and villages, posters suddenly appeared announcing that all able-bodied

men and women were to assemble in their local square at a given

time or face arrest and execution.

“The screaming, wailing and howling in the square will haunt me

the rest of my life,” remembered one horrified female.

Mercilessly the women were herded together in rows of four. Mothers had

to leave tiny children behind. I thanked God from the bottom of my heart that

my boy had died in Berlin shortly after birth.... The . . . wretched victims [were]

then set in motion to the crack of Russian whips. It was foggy and damp, and

a drizzling rain swept into our faces. The streets were icy and slippery; in many

places we waded ankle-deep in ice water. Before long one of the women collapsed,

and being unable to rise, remained lying there.

So we marched along, mile after mile. I had never believed it possible to go

so far on foot, but I was so indifferent that I scarcely could think. I just pushed

one foot along mechanically after the other. . . . Only rarely did we exchange

words. Each of my suffering fellow-creatures had enough torment of her own

and many had eyes swollen and sore from weeping.19

For those forced east on foot, the trek became little better than a death

march. Thousands dropped dead in their tracks from hunger, thirst,

disease, and abuse. “It took all of our remaining strength to stay in

the middle of the extremely slow-moving herds being driven east,” said

Wolfgang Kasak. “We kept hearing the submachine guns whenever a

straggler was shot. . . . I will never forget . . . the shooting of a 15-year old

boy right before my very eyes. He simply couldn’t walk anymore,

so a Russian soldier took potshots at him. The boy was still alive when

some officer came over and fired his gun into the boy’s ear.”20

“One young girl jumped from a bridge into the water, the guards shot

wildly at her, and I saw her sink,” recalled Anna Schwartz. “A young

man, who had heart-disease, jumped into the Vistula. He was also shot.

The fourth day we could hardly move further. Thirst was such a torture,

and we were so tired. Many had got open sores on their feet from

walking.”21

Those who traveled by rail to Siberia fared even worse. As one slave

recorded:

120 people were forced into each wagon, women and men separately....

The wagons were filthy from top to bottom, and there was not a blade of straw.

When the last man had been driven in by blows with rifle-butts, we could only

stand packed together like sardines. . . . When we were being loaded, the Russians

treated us like cattle, and many people became demented. A bucket of water

and crumbs of bread, served up to us on a filthy piece of tent canvas, were our

daily food. The worst part were the nights. Our legs got weak from continual

standing, and the one leant against the other.... [T]he journey lasted 28 days.

When the train stopped, mostly for the night, we were not left in peace. The

guards came to the wagons, and hammered on them from all sides. We could

not understand why this was done. But this happened almost every night. 10

to 15 men had already died during the first eight days. We others had to carry

out the corpses naked under guard, and they were piled up at the end of the train

like wood in empty wagons. Every day more and more died.

Our condition was made worse by the fact that in all the wagons there were

some Poles and Lithuanians. . . . They thought . . . that they had more rights than

we, and made room for themselves by lying on top of weak persons; they took

no notice when these screamed because of being stifled by the weight. When the

food came, they stormed it, and very little remained over for us Germans. We

slowly perished in the course of this death-journey.

Thirst was worse than hunger. The iron fittings of the wagons were damp

through the vapor and breath. Most of the people scratched this off with their

dirty fingers and sucked it; many of them got ill in this way. The mortality

increased from day to day, and the corpse wagons, behind the train, continually

increased in number.22

When the trains finally reached their destinations, there was substantially

more room in each car since a third to one half of all prisoners

normally died in transit. Continues the above witness:

The rest of us poor wretches looked like a crowd of walking corpses. After

we had stumbled out of the train, we had to parade in front of it. . . . We were

covered from head to foot with a crust of dirt and filth, and looked terrible.

The Russians led us in this state stumbling or rather creeping through the

roads of the Ural Mountains. The Russian population stood on the edge of the

road with terror in their faces, and watched the procession of all these miserable

people. Those who could not walk any further, were driven on, step by step, by

being struck with rifle-butts.

We now stopped in front of a sauna-bath. This was fatal for most of us. For

everyone was thirsty and rushed to the basins, which were full of dirty water,and each drank until he was full. This immediately caused the awful dysentery

illness. . . . When we finally came to camps, more than a half of what remained

of us poor wretches already had typhoid.23

“Now the dying really began . . . ,” remembered Anna Schwartz.

Our camp. . . was a large piece of land with a barbed wire fence, 2 metres

high. Within this fence, at a distance of 2 metres, there was another small barbed

wire fence, and we were not allowed to go near it. At every corner, outside the

fence, was a sentry turret, which was occupied by guards day and night. There

was a searchlight outside, which lit up the whole camp at night time....The huts,

in which we were quartered, were full of filth and vermin, swarms of bugs overwhelmed

us, and we destroyed as much of this vermin as we could. We lay on

bare boards so close together, that, if we wanted to turn round, we had to wake

our neighbors to the right and left of us, in order that we all turned round at

the same time. The sick people lay amongst us, groaning and in delirium....

Typhoid and dysentery raged and very many died, but death meant rather

release than terror to them. The dead were brought into a cellar, and when

this was full up to the top, it was emptied. Meanwhile the rats had eaten from

the corpses, and these very quickly decayed....Also the wolves satisfied their

hunger. . . .

After three weeks the doctors came to examine us medically. We went by

huts to the outside hospital, and had to strip ourselves naked; we then went

one by one into the so-called consulting room. When we opened the door, we

saw that the whole room was full of officers; this also upset us and caused

tears, but that did not help, we had to go in naked. . . . They laughed at our

blushing, and also at our figures, which were distorted through our having got

so thin. Some officers pinched our arms and legs, in order to test the firmness

of the flesh. This occurred every three months.24

While Anna’s camp worked on a railroad and was driven day-in, day-out

“like a herd of draught animals,” and while others toiled in fields,

factories, peat bogs, and lumber camps, thousands more were relegated

to the mines. Wrote Ilse Lau:

It is a strange feeling to be suddenly 120 metres beneath the earth. Around us

everything was dark, there was only one electric bulb for lighting the lift. We

lit our miners lamps, and then began working. . . . There was water everywhere

on the ground of the mine gallery. If one stepped carelessly from the rails, on

which the coal trucks were pushed along, one got wet up to the knees. . . . We sometimes had to remain as much as 16 hours down in the pit. When we had

finally finished our work by summoning up our last strength, we were not allowed

to go up in the lift, but had to climb up the ladders (138 metres). We were often

near to desperation. We were never able to sleep enough, and we were always

hungry.25

“Every day . . . in the coal-pit camp even as many as 15 to 25 died,”

added fellow slave, Gertrude Schulz. “At midnight the corpses were

brought naked on stretchers into the forest, and put into a mass grave.

. . . On Sundays our working hours were a little shorter, and ended at

5 o’clock in the afternoon. Then catholics and protestants assembled

. . . for divine service. Often a commissar came and shouted out:

‘That won’t help you.’”26

Just as faith in the Almighty was often the thin divide that separated

those who lived from those who died, so too did simple acts of

kindness offer strength and rays of hope in an otherwise crushing

gloom. As Wolfgang Kasak and his comrades stood dying of thirst, a

Russian woman appeared with buckets of water.

“The guards drove the woman away,” Kasak said. “But she kept on

bringing water, bucket after bucket, to the places where no Russians

were standing guard. I know now the Russian soldiers closed one eye

and took a long time in following their orders to keep the woman from

giving us something to drink.”27

Siegfried Losch, the youth who had become a recruit, soldier, veteran,

deserter, prisoner, and slave before he had seen his eighteenth

year, was at work one Sunday morning when an old grandmother

approached.

Her clothing indicated that she was very poor. Judging from her walk . . . she

suffered from osteosclerosis. Indeed, her figure was more like that of the witch

in Hansel and Gretl. But her face was different.... The face emanated . . .

warmth as only a mother who has suffered much can give. Here was the true

example of mother Russia: Having suffered under the Soviet regime, the war,

having possible lost one or more of her loved ones. . . . She probably was walking

toward her church. When she was near me, she stopped and gave me some

small coins. . . . Then she made a cross over me with tears in her eyes and walked on. I gave her a “spasibo” (thank you!) and continued my work. But

for the rest of the day I was a different person, because somebody cared, somebody

let her soul speak to me.28

Precious as such miracles might be, they were but cruel reminders

of a world that was no more. “We were eternally hungry . . . ,” recalled

Erich Gerhardt.

Precious as such miracles might be, they were but cruel reminders

of a world that was no more. “We were eternally hungry . . . ,” recalled

Erich Gerhardt.

Treatment by the Russian guards was almost always very bad. We were simply walking skeletons. . . . From the first to the last day our life was a ceaseless suffering, a dying and lamentation. The Russian guards mercilessly pushed the very weakest people forward with their rifle-butts, when they could hardly move. When the guards used their rifle-butts, they made use of the words, “You lazy rascal.” I was already so weak, that I wanted to be killed on the spot by the blows.29

“We were always hungry and cold, and covered with vermin . . . ,” echoed a fellow slave. “I used to pray to God to let me at least die in my native country.”30

Cruelly, had this man’s prayers been answered and had he been allowed to return to Germany, the odds were good indeed that he would have died in his homeland . . . and sooner than he imagined. Unbeknownst to these wretched prisoners dreaming of home, the situation in the former Reich differed little, if any, from that of Siberia. Indeed, in many cases, “life” in the defeated nation was vastly worse.

No measures were to be undertaken, wrote the US government to

General Eisenhower, “looking toward the economic rehabilitation of

Germany or designed to maintain or strengthen the German economy.”Not

only would food from the outside be denied entry, but troops

were forbidden to “give, sell or trade” supplies to the starving. Additionally,

Germany’s already meager ability to feed itself would be

sharply stymied by withholding seed crop, fertilizer, gas, oil, and

parts for farm machinery. Because of the enforced famine, it was

estimated that thirty million Germans would soon succumb.31 Well

down the road to starvation even before surrender, those Germans

who survived war now struggled to survive peace. [That they did this as Americans just totally disgusts me.DC]

No measures were to be undertaken, wrote the US government to

General Eisenhower, “looking toward the economic rehabilitation of

Germany or designed to maintain or strengthen the German economy.”Not

only would food from the outside be denied entry, but troops

were forbidden to “give, sell or trade” supplies to the starving. Additionally,

Germany’s already meager ability to feed itself would be

sharply stymied by withholding seed crop, fertilizer, gas, oil, and

parts for farm machinery. Because of the enforced famine, it was

estimated that thirty million Germans would soon succumb.31 Well

down the road to starvation even before surrender, those Germans

who survived war now struggled to survive peace. [That they did this as Americans just totally disgusts me.DC]

“I trudged home on sore feet, limp with hunger . . . ,” a Berlin woman

scribbled in her diary. “It struck me that everyone I passed on the way

home stared at me out of sunken, starving eyes. Tomorrow I’ll go in

search of nettles again. I examine every bit of green with this in mind.”32

“I trudged home on sore feet, limp with hunger . . . ,” a Berlin woman

scribbled in her diary. “It struck me that everyone I passed on the way

home stared at me out of sunken, starving eyes. Tomorrow I’ll go in

search of nettles again. I examine every bit of green with this in mind.”32

“The search for food made all former worries irrelevant,” added Lali Horstmann. “It was the present moment alone that counted.”33

While city-dwellers ate weeds, those on the land had food taken from them and were forced to dig roots, pick berries and glean fields.“Old men, women and children,” a witness noted, “may be seen picking up one grain at a time from the ground to be carried home in a sack the size of a housewife’s shopping bag.”34

The deadly effects of malnutrition soon became evident. Wrote one horrified observer:

They are emaciated to the bone. Their clothes hang loose on their bodies, the lower extremities are like the bones of a skeleton, their hands shake as though with palsy, the muscles of the arms are withered, the skin lies in folds, and is without elasticity, the joints spring out as though broken. The weight of the women of average height and build has fallen way below 110 pounds. Often women of child-bearing age weigh no more than 65 pounds.35

“We were really starving now . . . ,” said Ilse McKee.“Most of the time we were too weak to do anything. Even queuing up for what little food there was to be distributed sometimes proved too much.”36

Orders to the contrary, many Allied soldiers secretly slipped chocolate to children or simply turned their backs while elders stole bread. Others were determined to follow orders implacably. “It was a common sight,” recalled one GI,“to see German women up to their elbows in our garbage cans looking for something edible—that is, if they weren’t chased away.”37 To prevent starving Germans from grubbing American leftovers, army cooks laced their slop with soap. Tossing crumbs or used chewing gum to scrambling children was another pastime some soldiers found amusing.38

For many victims, especially the old and young, even begging and stealing proved too taxing and thousands slipped slowly into the final, fatal apathy preceding death.

“Most children under 10 and people over 60 cannot survive the coming winter,” one American admitted in October 1945. 39

“The number of still-born children is approaching the number of those born alive, and an increasing proportion of these die in a few days,” added another witness to the tragedy. “Even if they come into the world of normal weight, they start immediately to lose weight and die shortly. Very often mothers cannot stand the loss of blood in childbirth and perish. Infant mortality has reached the horrifying height of 90 per cent.”40

“Millions of these children must die before there is enough food,” echoed an American clergyman traveling in Germany. “In Frankfurt at a children’s hospital there have been set aside 25 out of 100 children. These will be fed and kept alive. It is better to feed 25 enough to keep them alive and let 75 starve than to feed the 100 for a short while and let them all starve.”41

From Wiesbaden, a correspondent of the Chicago Daily News reported:

I sat with a mother, watching her eight-year-old daughter playing with a doll and carriage, her only playthings. . . . Her legs were tiny, joints protruding. Her arms had no flesh. Her skin drawn taut across the bones, the eyes dark, deep-set and tired.

“She doesn’t look well,” I said.

“Six years of war,” the mother replied, in that quiet toneless manner so common here now. “She hasn’t had a chance. None of the children have. Her teeth are not good. She catches illness so easily. She laughs and plays—yes; but soon she is tired. She never has known”—and the mother’s eyes filled with tears— ”what it is not to be hungry.”

“Was it that bad during the war?” I asked.

“Not this bad,” she replied, “but not good at all. And now I am told the bread ration is to be less. What are we to do; all of us? For six years we suffered. We love our country. My husband was killed—his second war. My oldest son is a prisoner somewhere in France. My other boy lost a leg. . . . And now. . . .”

By this time she was weeping. I gave this little girl a Hershey bar and she wept— pure joy—as she held it. By this time I wasn’t feeling too chipper myself.42

When a scattering of reports like the above began filtering out to the American and British public's, many were shocked, horrified and outraged at the secret slaughter being committed in their name. Already troubled that the US State Department had tried to keep an official report on conditions in Germany from public scrutiny, Senator James Eastland of Mississippi was forced to concede:

There appears to be a conspiracy of silence to conceal from our people the true picture of conditions in Europe, to secrete from us the fact regarding conditions of the continent and information as to our policies toward the German people. . . . Are the real facts withheld because our policies are so cruel that the American people would not endorse them?

What have we to hide, Mr. President? Why should these facts be withheld from the people of the United States? There cannot possibly be any valid reason for secrecy. Are we following a policy of vindictive hatred, a policy which would not be endorsed by the American people as a whole if they knew true conditions?43

“Yes,” replied a chamber colleague, Senator Homer Capehart of Indiana:

The fact can no longer be suppressed, namely, the fact that it has been and continues to be, the deliberate policy of a confidential and conspiratorial clique within the policy-making circles of this government to draw and quarter a nation now reduced to abject misery. In this process this clique, like a pack of hyenas struggling over the bloody entrails of a corpse, and inspired by a sadistic and fanatical hatred, are determined to destroy the German nation and the German people, no matter what the consequences....

The cynical and savage repudiation of . . . not only . . . the Potsdam Declaration, but also of every law of God and men, has been deliberately engineered with such a malevolent cunning, and with such diabolical skill, that the American people themselves have been caught in an international death trap.... This administration has been carrying on a deliberate policy of mass starvation without any distinction between the innocent and the helpless and the guilty alike.44

The murderous program was, wrote an equally outraged William Henry Chamberlain, “a positively sadistic desire to inflict maximum suffering on all Germans, irrespective of their responsibility for Nazi crimes.”45

Surprisingly, one of the most strident voices raised against the silent massacre was that of influential Jewish journalist, Victor Gollancz. It was not a matter of whether one was “pro-German” or “anti-Soviet,” argued the London publisher, but whether or not a person was “prohumanity.”46

The plain fact is . . . we are starving the German people. . . . Others, including ourselves, are to keep or be given comforts while the Germans lack the bare necessities of existence. If it is a choice between discomfort for another and suffering for the German, the German must suffer; if between suffering for another and death for the German, the German must die.47

Although Gollancz felt the famine was not engineered, but rather

a result of incompetence and indifference, others disagreed.

Although Gollancz felt the famine was not engineered, but rather

a result of incompetence and indifference, others disagreed.

“On the contrary,” raged the Chicago Daily Tribune, “it is the product of foresight. It was deliberately planned at Yalta by Roosevelt, Stalin, and Churchill, and the program in all its brutality was later confirmed by Truman, Attlee, and Stalin. . . . The intent to starve the German people to death is being carried out with a remorselessness unknown in the western world since the Mongol conquest.”48

Because of these and other critics, Allied officials were forced to respond. Following a fact-finding tour of Germany, Eleanor Roosevelt, wife of the late president, professed to see no suffering beyond what was considered “tolerable.”And General Eisenhower, pointing out that there were food shortages all throughout Europe, noted that Germany suffered no more nor less than its neighbors. “While I and my subordinates believe that stern justice should be meted out to war criminals . . . we would never condone inhuman or un-American practices upon the helpless,” assured the general as Germans died by the thousands in his death camps.49 [What a liar DC]

Although some nations were indeed suffering shortages, none save Germany was starving. Many countries were actually experiencing surpluses of food, including Denmark on Germany’s north border, a nation only waiting Eisenhower’s nod to send tons of excess beef south.50

“England is not starving . . . ,” argued Robert Conway in the New York News. “France is better off than England, and Italy is better off than France.”51

When Senator Albert Hawkes of New Jersey pleaded with President Truman to head off catastrophe and allow private relief packages to enter Germany, the American leader offered various excuses, then cut the senator short:

While we have no desire to be unduly cruel to Germany, I cannot feel any great sympathy for those who caused the death of so many human beings by starvation, disease, and outright murder, in addition to all the destruction and death of war. . . . I think that . . . no one should be called upon to pay for Germany’s misfortune except Germany itself. . . . Eventually the enemy countries will be given some attention.52[Another liar and disgrace D.C]

In time, Germany did receive “some attention.” Late in 1945, the British allowed Red Cross shipments to enter their zone, followed by the French in theirs. Months later, even the United States grudgingly permitted supplies to cross into its sector.53 For thousands upon thousands of Germans, however, the food came far too late.

“Rape represents no problem to the military police because,” explained an American officer matter-of-factly, “a bit of food, a bar of chocolate, or a bar of soap seems to make rape unnecessary.”54

“Young girls, unattached, wander about and freely offer themselves for food or bed . . . ,” reported the London Weekly Review. “Very simply they have one thing left to sell, and they sell it.”55

“Bacon, eggs, sleep at your home?” winked Russian soldiers over and over again, knowing full well the answer would usually be a five-minute tryst among the rubble. “I continually ran about with cooking utensils, and begged for food . . . ,”admitted one girl.“If I heard in my neighborhood the expression ‘pretty woman,’ I reacted accordingly.”56

Despite Eisenhower’s edict against fraternization with the despised enemy, no amount of words could slow the US soldier’s sex drive.“Neither army regulations nor the propaganda of hatred in the American press,” noted newswoman, Freda Utley, “could prevent American soldiers from liking and associating with German women, who although they were driven by hunger to become prostitutes, preserved a certain innate decency.”57

Treatment by the Russian guards was almost always very bad. We were simply walking skeletons. . . . From the first to the last day our life was a ceaseless suffering, a dying and lamentation. The Russian guards mercilessly pushed the very weakest people forward with their rifle-butts, when they could hardly move. When the guards used their rifle-butts, they made use of the words, “You lazy rascal.” I was already so weak, that I wanted to be killed on the spot by the blows.29

“We were always hungry and cold, and covered with vermin . . . ,” echoed a fellow slave. “I used to pray to God to let me at least die in my native country.”30

Cruelly, had this man’s prayers been answered and had he been allowed to return to Germany, the odds were good indeed that he would have died in his homeland . . . and sooner than he imagined. Unbeknownst to these wretched prisoners dreaming of home, the situation in the former Reich differed little, if any, from that of Siberia. Indeed, in many cases, “life” in the defeated nation was vastly worse.

☭☠☭☠☭

Because German’s entire infrastructure had been shattered by the war,

it was already assured that thousands would starve to death before

roads, rails, canals, and bridges could be restored. Even when much

of the damage had been repaired, the deliberate withholding of food

from Germany guaranteed that hundreds of thousands more were

doomed to slow death. Continuing the policy of their predecessors,

Harry Truman and Clement Attlee allowed the spirit of Yalta and Morgenthau

to dictate their course regarding post-war Germany.“The search for food made all former worries irrelevant,” added Lali Horstmann. “It was the present moment alone that counted.”33

While city-dwellers ate weeds, those on the land had food taken from them and were forced to dig roots, pick berries and glean fields.“Old men, women and children,” a witness noted, “may be seen picking up one grain at a time from the ground to be carried home in a sack the size of a housewife’s shopping bag.”34

The deadly effects of malnutrition soon became evident. Wrote one horrified observer:

They are emaciated to the bone. Their clothes hang loose on their bodies, the lower extremities are like the bones of a skeleton, their hands shake as though with palsy, the muscles of the arms are withered, the skin lies in folds, and is without elasticity, the joints spring out as though broken. The weight of the women of average height and build has fallen way below 110 pounds. Often women of child-bearing age weigh no more than 65 pounds.35

“We were really starving now . . . ,” said Ilse McKee.“Most of the time we were too weak to do anything. Even queuing up for what little food there was to be distributed sometimes proved too much.”36

Orders to the contrary, many Allied soldiers secretly slipped chocolate to children or simply turned their backs while elders stole bread. Others were determined to follow orders implacably. “It was a common sight,” recalled one GI,“to see German women up to their elbows in our garbage cans looking for something edible—that is, if they weren’t chased away.”37 To prevent starving Germans from grubbing American leftovers, army cooks laced their slop with soap. Tossing crumbs or used chewing gum to scrambling children was another pastime some soldiers found amusing.38

For many victims, especially the old and young, even begging and stealing proved too taxing and thousands slipped slowly into the final, fatal apathy preceding death.

“Most children under 10 and people over 60 cannot survive the coming winter,” one American admitted in October 1945. 39

“The number of still-born children is approaching the number of those born alive, and an increasing proportion of these die in a few days,” added another witness to the tragedy. “Even if they come into the world of normal weight, they start immediately to lose weight and die shortly. Very often mothers cannot stand the loss of blood in childbirth and perish. Infant mortality has reached the horrifying height of 90 per cent.”40

“Millions of these children must die before there is enough food,” echoed an American clergyman traveling in Germany. “In Frankfurt at a children’s hospital there have been set aside 25 out of 100 children. These will be fed and kept alive. It is better to feed 25 enough to keep them alive and let 75 starve than to feed the 100 for a short while and let them all starve.”41

From Wiesbaden, a correspondent of the Chicago Daily News reported:

I sat with a mother, watching her eight-year-old daughter playing with a doll and carriage, her only playthings. . . . Her legs were tiny, joints protruding. Her arms had no flesh. Her skin drawn taut across the bones, the eyes dark, deep-set and tired.

“She doesn’t look well,” I said.

“Six years of war,” the mother replied, in that quiet toneless manner so common here now. “She hasn’t had a chance. None of the children have. Her teeth are not good. She catches illness so easily. She laughs and plays—yes; but soon she is tired. She never has known”—and the mother’s eyes filled with tears— ”what it is not to be hungry.”

“Was it that bad during the war?” I asked.

“Not this bad,” she replied, “but not good at all. And now I am told the bread ration is to be less. What are we to do; all of us? For six years we suffered. We love our country. My husband was killed—his second war. My oldest son is a prisoner somewhere in France. My other boy lost a leg. . . . And now. . . .”

By this time she was weeping. I gave this little girl a Hershey bar and she wept— pure joy—as she held it. By this time I wasn’t feeling too chipper myself.42

When a scattering of reports like the above began filtering out to the American and British public's, many were shocked, horrified and outraged at the secret slaughter being committed in their name. Already troubled that the US State Department had tried to keep an official report on conditions in Germany from public scrutiny, Senator James Eastland of Mississippi was forced to concede:

There appears to be a conspiracy of silence to conceal from our people the true picture of conditions in Europe, to secrete from us the fact regarding conditions of the continent and information as to our policies toward the German people. . . . Are the real facts withheld because our policies are so cruel that the American people would not endorse them?

What have we to hide, Mr. President? Why should these facts be withheld from the people of the United States? There cannot possibly be any valid reason for secrecy. Are we following a policy of vindictive hatred, a policy which would not be endorsed by the American people as a whole if they knew true conditions?43

“Yes,” replied a chamber colleague, Senator Homer Capehart of Indiana:

The fact can no longer be suppressed, namely, the fact that it has been and continues to be, the deliberate policy of a confidential and conspiratorial clique within the policy-making circles of this government to draw and quarter a nation now reduced to abject misery. In this process this clique, like a pack of hyenas struggling over the bloody entrails of a corpse, and inspired by a sadistic and fanatical hatred, are determined to destroy the German nation and the German people, no matter what the consequences....

The cynical and savage repudiation of . . . not only . . . the Potsdam Declaration, but also of every law of God and men, has been deliberately engineered with such a malevolent cunning, and with such diabolical skill, that the American people themselves have been caught in an international death trap.... This administration has been carrying on a deliberate policy of mass starvation without any distinction between the innocent and the helpless and the guilty alike.44

The murderous program was, wrote an equally outraged William Henry Chamberlain, “a positively sadistic desire to inflict maximum suffering on all Germans, irrespective of their responsibility for Nazi crimes.”45

Surprisingly, one of the most strident voices raised against the silent massacre was that of influential Jewish journalist, Victor Gollancz. It was not a matter of whether one was “pro-German” or “anti-Soviet,” argued the London publisher, but whether or not a person was “prohumanity.”46

The plain fact is . . . we are starving the German people. . . . Others, including ourselves, are to keep or be given comforts while the Germans lack the bare necessities of existence. If it is a choice between discomfort for another and suffering for the German, the German must suffer; if between suffering for another and death for the German, the German must die.47

“On the contrary,” raged the Chicago Daily Tribune, “it is the product of foresight. It was deliberately planned at Yalta by Roosevelt, Stalin, and Churchill, and the program in all its brutality was later confirmed by Truman, Attlee, and Stalin. . . . The intent to starve the German people to death is being carried out with a remorselessness unknown in the western world since the Mongol conquest.”48

Because of these and other critics, Allied officials were forced to respond. Following a fact-finding tour of Germany, Eleanor Roosevelt, wife of the late president, professed to see no suffering beyond what was considered “tolerable.”And General Eisenhower, pointing out that there were food shortages all throughout Europe, noted that Germany suffered no more nor less than its neighbors. “While I and my subordinates believe that stern justice should be meted out to war criminals . . . we would never condone inhuman or un-American practices upon the helpless,” assured the general as Germans died by the thousands in his death camps.49 [What a liar DC]

Although some nations were indeed suffering shortages, none save Germany was starving. Many countries were actually experiencing surpluses of food, including Denmark on Germany’s north border, a nation only waiting Eisenhower’s nod to send tons of excess beef south.50

“England is not starving . . . ,” argued Robert Conway in the New York News. “France is better off than England, and Italy is better off than France.”51

When Senator Albert Hawkes of New Jersey pleaded with President Truman to head off catastrophe and allow private relief packages to enter Germany, the American leader offered various excuses, then cut the senator short:

While we have no desire to be unduly cruel to Germany, I cannot feel any great sympathy for those who caused the death of so many human beings by starvation, disease, and outright murder, in addition to all the destruction and death of war. . . . I think that . . . no one should be called upon to pay for Germany’s misfortune except Germany itself. . . . Eventually the enemy countries will be given some attention.52[Another liar and disgrace D.C]

In time, Germany did receive “some attention.” Late in 1945, the British allowed Red Cross shipments to enter their zone, followed by the French in theirs. Months later, even the United States grudgingly permitted supplies to cross into its sector.53 For thousands upon thousands of Germans, however, the food came far too late.

☠☭☠☭☠

Even as the starvation of Germany was in progress, the defilement of

German womanhood continued without pause. Although violent, brutal

and repeated rapes persisted against defenseless females, Russian,

American, British, and French troops quickly discovered that hunger

was a powerful incentive to sexual surrender. “Rape represents no problem to the military police because,” explained an American officer matter-of-factly, “a bit of food, a bar of chocolate, or a bar of soap seems to make rape unnecessary.”54

“Young girls, unattached, wander about and freely offer themselves for food or bed . . . ,” reported the London Weekly Review. “Very simply they have one thing left to sell, and they sell it.”55

“Bacon, eggs, sleep at your home?” winked Russian soldiers over and over again, knowing full well the answer would usually be a five-minute tryst among the rubble. “I continually ran about with cooking utensils, and begged for food . . . ,”admitted one girl.“If I heard in my neighborhood the expression ‘pretty woman,’ I reacted accordingly.”56

Despite Eisenhower’s edict against fraternization with the despised enemy, no amount of words could slow the US soldier’s sex drive.“Neither army regulations nor the propaganda of hatred in the American press,” noted newswoman, Freda Utley, “could prevent American soldiers from liking and associating with German women, who although they were driven by hunger to become prostitutes, preserved a certain innate decency.”57

“I felt a bit sick at times about the power I had over that girl,” one troubled British soldier said.“If I gave her a three-penny bar of chocolate she nearly went crazy. She was just like my slave. She darned my socks and mended things for me. There was no question of marriage. She knew that was not possible.”58

As this young Tommy made clear, desperate German women, many with children to feed, were compelled by hunger to enter a bondage as binding as any in history. With time, some victims, particularly those consorting with officers, not only avoided starvation, but found themselves enjoying luxuries long forgotten.

“You should have seen all the things he brought me, just so I wouldn’t lack for anything!” recalled one woman kept by an officer on Patton’s staff.“Nylon stockings, and the newest records, perfume, and two refrigerators, and of course loads of cigarettes and alcohol and gas for the car. . . . It was a wild time—the champagne flowed in streams, and when we weren’t totally drunk, we made love.”59

Unlike the above, relatively few females found such havens. For most, food was used to bait or bribe them into a slavery as old and unforgiving as the Bible. Wrote Lali Horstmann from the Russian Zone:

He announced that women were needed to peel potatoes in a soldiers’ camp and asked for volunteers. Their work would be paid for with soup and potatoes. The girl next to me whispered: “My sister was taken away four days ago on the same pretext and has not returned yet. A friend of mine escaped and brought back stories of what happened to her and the others.”

When a frail, hungry-looking, white-haired woman lifted her arm to offer her services, the golden-toothed one did not even glance at her, but pointed his pistol at the young girl . . . of whom the others had been talking. As she did not move, he gave a rough command. Two soldiers came to stand beside him, four more walked right and left of the single file of women until they reached her and ordered her to get into the truck. She was in tears as she was brutally shoved forward, followed by others who were protesting helplessly.60

“A Pole discovered me, and began to sell me to Russians,” another girl confessed.

He had fixed up a brothel in his cellar for Russian officers. I was fetched by him. . . . I had to go with him, and could not resist. I came into the cellar, in which there were the most depraved carryings on, drinking, smoking and shouting, and I had to participate. . . . I felt like shrieking.

Then a room was opened, and the door shut behind me. Then I saw how the Pole did a deal with a Russian, and received money. My value was fixed at 800 zlotys. The Russian then gave me 200 zlotys for myself, which he put in my pocket. I did not give him the money back, because I could buy food....

My employer . . . was continually after me, and followed me even when I went into the cellar. I was chased about like a frightened deer, he even turned up in the wash-house if he thought I was there. We often had a struggle but how was I to escape him? I could not run away, or complain to anyone, but had to keep to my work, as I had my mother with me. I did as little as I could. It was, however, not possible to avoid everything.61

While many women endured such slavery—if only to eat—others risked their all to escape. Remembered an American journalist:

As our long line of British Army lorries . . . rolled through the main street of Brahlstorf, the last Russian occupied town, a pretty blond girl darted from the crowd of Germans watching us and made a dash for our truck. Clinging with both hands to the tailboard, she made a desperate effort to climb in. But we were driving too fast and the board was too high. After being dragged several hundred yards she had to let go and fell on the cobblestone street. That scene was a dramatic illustration of the state of terror in which women . . . were living.62

☠☭☠

By the summer of 1945, Germany had become the world’s greatest slave

market where sex was the new medium of exchange. While the wolf

of hunger might be kept from the door, grim disease was almost always

waiting in the wings. “As a way of dying it may be worse than starvation, but it will put off dying for months—or even years,” commented an English journalist.63

In addition to all the venereal diseases known in the West, German women were infected by a host of new evils, including an insidious strain of Asiatic syphilis. “It is a virulent form of sickness, unknown in this part of the world,” a doctor’s wife explained. “It would be difficult to cure even if we were lucky enough to have any penicillin.”64

Another dreaded concern—not only for those who were selling themselves, but for the millions of rape victims—was unwanted pregnancy. Thousands who were if fact pregnant sought and found abortions. Thousands more lived in dreadful suspense. Jotted one Berlin woman in her diary:

I calculated that I’m now just two weeks overdue. So I decided to consult a woman’s doctor whose sign I had seen on a house round the corner. She turned out to be a blond woman of about my age, practicing in a semi-gutted room. She had replaced the missing windowpanes with X-ray negatives of human chests. She refused to talk and went straight to work. “No,” she said, after the examination, “I can’t find a thing. You’re all right.”

“But I’m overdue. That’s never happened to me before.”

“Don’t be silly! It’s happening to almost every woman nowadays. I’m overdue myself. It’s lack of food. The body’s saving its blood. Try and put some flesh on your ribs. Then things’ll begin to work again.”

She charged me 10 Marks—which I gave her with a bad conscience.... Finally I risked asking her if women made pregnant by Russians come to her for help. “I’d rather not talk about that,” she said dryly, and let me go.65

And for those infants who were carried and delivered, their struggle was usually brief.

“The mortality among the small children and infants was very high,” wrote one woman.“They simply had to starve to death. There was nothing for them. . . . Generally, they did not live to be more than 3 months old—a consolation for those mothers, who had got the child against their will from a Russian. . . . The mother worked all the time and was very seldom able to give the child the breast.”66

As the above implied, simply because a mother sold her body to feed a child did not necessarily save her from back-breaking labor. Indeed, with the end of war, Germans old and young were dragooned by the victors for the monumental clean-up and dismantling of the devastated Reich. Sometimes food was given to the workers—“a piece of bread or maybe a bowl of thin, watery soup”—and sometimes not.“We used to start work at six o’clock in the morning and get home again at six in the evening,” said a Silesian woman. “We had to work on Sundays, too, and we were given neither payment nor food for what we did.”67

From the blasted capital, another female recorded:

Berlin is being cleaned up. . . . All round the hills of rubble, buckets were being passed from hand to hand; we have returned to the days of the Pyramids—except that instead of building we are carrying away. . . . On the embankment German prisoners were slaving away—gray-heads in miserable clothes, presumably ex-Volksturm. With grunts and groans, they were loading heavy wheels onto freight-cars. They gazed at us imploringly, tried to keep near us. At first I couldn’t understand why. Others did, though, and secretly passed the men a few crusts of bread. This is strictly forbidden, but the Russian guard stared hard in the opposite direction. The men were unshaven, shrunken, with wretched doglike expressions. To me they didn’t look German at all.68

“My mother, 72 years of age, had to work outside the town on refuse heaps,” lamented a daughter in Posen. “There the old people were hunted about, and had to sort out bottles and iron, even when it was raining or snowing. The work was dirty, and it was impossible for them to change their clothes.”69

Understandably, thousands of overworked, underfed victims soon succumbed under such conditions. No job was too low or degrading for the conquered Germans to perform. Well-bred ladies, who in former times were theater-going members of the upper-class, worked side by side with peasants at washtubs, cleaning socks and underclothes of Russian privates. Children and the aged were put to work scrubbing floors and shining boots in the American, British and French Zones. Some tasks were especially loathsome, as one woman makes clear:“As a result of the war damage . . . the toilets were stopped up and filthy. This filth we had to clear away with our hands, without any utensils to do so. The excrement was brought into the yard, shoveled into carts,which we had to bring to refuse pits. The awful part was, that we got dirtied by the excrement which spurted up, but we could not clean ourselves.”70

Added another female from the Soviet Zone:

We had to build landing strips, and to break stones. In snow and rain, from six in the morning until nine at night, we were working along the roads. Any Russian who felt like it took us aside. In the morning and at night we received cold water and a piece of bread, and at noon soup of crushed, unpeeled potatoes, without salt. At night we slept on the floors of farmhouses or stables, dead tired, huddled together. But we woke up every so often, when a moaning and whimpering in the pitch-black room announced the presence of one of the guards.71

As this woman and others make clear, although sex could be bought for a bit of food, a cigarette or a bar of soap, some victors preferred to take what they wanted, whenever and wherever they pleased. “If they wanted a girl they just came in the field and got her,” recalled Ilse Breyer who worked at planting potatoes.72

“Hunger made German women more ‘available,’” an American soldier revealed, “but despite this, rape was prevalent and often accompanied by additional violence. In particular I remember an eighteen-year old woman who had the side of her face smashed with a rifle butt and was then raped by two GIs. Even the French complained that the rapes, looting and drunken destructiveness on the part of our troops was excessive.”73

Had rapes, starvation and slavery been the only trials Germans were forced to endure, it would have been terrible enough. There were other horrors ahead, however—some so sadistic and evil as to stagger the senses. The nightmarish fate that befell thousands of victims locked deep in Allied prisons was enough, moaned one observer, to cause even the most devout to ask “if there really were such a thing as a God.”

next

The Halls of Hell

Notes

1. Crawley, The Spoils of War, 30.

2. Keeling, Gruesome Harvest, 1.

3. Barnouw, Germany 1945, 17–18.

4. Constantine FitzGibbon, Denazification (New York: W.W. Norton, 1969), 86.

5. Crawley, Spoils, 30.

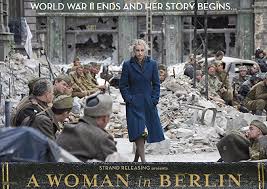

6. Anonymous, Woman in Berlin, 308–309.

7. Garrett, Ethics and Airpower, xi; Thomas Weyersberg Collections (copy in author’s possession);

McKee, Dresden 1945, 182.

8. Horstmann, We Chose to Stay, 117.

9. Keeling, Gruesome Harvest, 67.

10. Botting, Ruins of the Reich, 122; Keeling, xii.

11. Davidson, Death and Life of Germany, 6; Keeling, 83.

12. Keeling, xi.

13. Ibid., 51–52.

14. Schieder, Expulsion of the German Population, 242.

15. Shelton, To Lose a War, 138.

16. Keeling, Gruesome Harvest, 52, 53.

17. Walendy, Methods of Reeducation, 17.

18. Ibid.

19. Lutz, “Rape of Christian Europe,” 14.

20. Pechel, et all, Voices From the Third Reich, 520.

21. Schieder, Expulsion, 180.

22. Ibid., 161.

23. Ibid., 161–162.

24. Ibid., 181, 182.

25. Ibid., 170, 171.

26. Ibid., 175.

27. Pechel, Voices, 520.

28. Losch Manuscript, 35–36.

29. Schieder, Expulsion, 159.

30. Kaps, Tragedy of Silesia, 167

31. Freda Utley, The High Cost of Vengeance (Chicago: Henry Regnery Co., 1949), 16; Davidson, Death and Life, 86; Interview with Martha Dodgen, Topeka, Kansas, Dec. 12, 1996.

32. Anonymous, Woman, 303.

33. Horstmann, We Chose to Stay, 123.

34. Keeling, Gruesome Harvest, 68.

35. Ibid., 71–72.

36. McKee, Tomorrow the World, 150–151.

37. Brech, “Eisenhower’s Death Camps,” 165.

38. Interview with Amy Schrott Krubel, Topeka, Kansas, Jan. 9, 1997.

39. Keeling, 73.

40. Ibid., 72.

41. Ibid., 72–73.

42. Ibid., 72.

43. Ibid., 76.

44. Ibid., 75.

45. Ibid., 82.

46. Barnouw, Germany 1945, 151.

47. Keeling, 77.

48. Ibid.

49. Ibid., 80, 81.

50. Ibid., 78.

51. Ibid.

52. Ibid., 80.

53. De Zayas, Nemesis at Potsdam, 133.

54. Keeling, Gruesome Harvest, 64.

55. Ibid., 64.

56. Schieder, Expulsion, 259.

57. Utley, High Cost, 17.

58. Botting, From the Ruins of the Reich, 250.

59. Bernt Engelmann, In Hitler’s Germany (New York: Pantheon, 1986), 334–335.

60. Horstmann, We Chose to Stay, 105.

61. Schieder, Expulsion, 268.

62. Keeling, 59.

63. Ibid., 64.

64. Horstmann, 106.

65. Anonymous, Woman in Berlin, 301–302.

66. Schieder, Expulsion, 276.

67. Kaps, Tragedy of Silesia, 149.

68. Anonymous, Woman in Berlin, 268, 287.

69. Schieder, 257.

70. Ibid., 256.

71. Thorwald, Flight in the Winter, 181.

72. Interview with Ilse Breyer Broderson, Independence, Missouri, Sept. 12, 1997.

73. Brech, “Eisenhower’s Death Camps,” 165.

28. Losch Manuscript, 35–36.

29. Schieder, Expulsion, 159.

30. Kaps, Tragedy of Silesia, 167

31. Freda Utley, The High Cost of Vengeance (Chicago: Henry Regnery Co., 1949), 16; Davidson, Death and Life, 86; Interview with Martha Dodgen, Topeka, Kansas, Dec. 12, 1996.

32. Anonymous, Woman, 303.

33. Horstmann, We Chose to Stay, 123.

34. Keeling, Gruesome Harvest, 68.

35. Ibid., 71–72.

36. McKee, Tomorrow the World, 150–151.

37. Brech, “Eisenhower’s Death Camps,” 165.

38. Interview with Amy Schrott Krubel, Topeka, Kansas, Jan. 9, 1997.

39. Keeling, 73.

40. Ibid., 72.

41. Ibid., 72–73.

42. Ibid., 72.

43. Ibid., 76.

44. Ibid., 75.

45. Ibid., 82.

46. Barnouw, Germany 1945, 151.

47. Keeling, 77.

48. Ibid.

49. Ibid., 80, 81.

50. Ibid., 78.

51. Ibid.

52. Ibid., 80.

53. De Zayas, Nemesis at Potsdam, 133.

54. Keeling, Gruesome Harvest, 64.

55. Ibid., 64.

56. Schieder, Expulsion, 259.

57. Utley, High Cost, 17.

58. Botting, From the Ruins of the Reich, 250.

59. Bernt Engelmann, In Hitler’s Germany (New York: Pantheon, 1986), 334–335.

60. Horstmann, We Chose to Stay, 105.

61. Schieder, Expulsion, 268.

62. Keeling, 59.

63. Ibid., 64.

64. Horstmann, 106.

65. Anonymous, Woman in Berlin, 301–302.

66. Schieder, Expulsion, 276.

67. Kaps, Tragedy of Silesia, 149.

68. Anonymous, Woman in Berlin, 268, 287.

69. Schieder, 257.

70. Ibid., 256.

71. Thorwald, Flight in the Winter, 181.

72. Interview with Ilse Breyer Broderson, Independence, Missouri, Sept. 12, 1997.

73. Brech, “Eisenhower’s Death Camps,” 165.

No comments:

Post a Comment