Going to restart another book that was disappeared at my last blog. Seeing we are staying at least 3 more years in Afghanistan,maybe at least one person will read this and understand why we are in Afghanistan. It has nothing to do with so called terrorists,and everything to do with the poppy plant.

The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia

By Alfred W. McCoy with

Cathleen B. Read and Leonard P.Adams II

Introduction:

The Consequences of Complicity

AMERICA is in the grip of a devastating heroin epidemic which leaves no city or suburb untouched, and

which also runs rampant through every American military installation both here and abroad. And the

plague is spreading-into factories and offices (among the middle-aged, middle-class workers as well as the

young), into high schools and now grammar schools. In 1965 federal narcotics officials were convinced

that they had the problem under control; there were only 57,000 known addicts in the entire country, and

most of these were comfortably out of sight, out of mind in black urban ghettos.(1)* Only three or four

years later heroin addiction began spreading into white communities, and by late 1969 the estimated

number of addicts jumped to 315,000. By late 1971 the estimated total had almost doubled-reaching an all time

high of 560,000.(2) One medical researcher discovered that 6.5 percent of all the blue-collar factory

workers he tested were heroin addicts,(3) and army medical doctors were convinced that 10 to 15 percent

of the G.I's in Vietnam were heroin users.(4) In sharp contrast to earlier generations of heroin users, many of

these newer addicts were young and relatively affluent.

The sudden rise in the addict population has spawned a crime wave that has turned America's inner cities

into concrete jungles. Addicts are forced to steal in order to maintain their habits, and they now account for

more than 75 percent of America's urban crime.(5) After opinion polls began to show massive public

concern over the heroin problem, President Nixon declared a "war on drugs" in a June 1971 statement to

Congress. He urged passage of a $370 million emergency appropriation to fight the heroin menace.

However, despite politically motivated claims of success in succeeding months by administration

spokesmen, heroin continues to flood into the country in unprecedented quantities, and there is every

indication that the number of hard-core addicts is increasing daily.

Heroin: The History of a "Miracle Drug"

Heroin, a relatively recent arrival on the drug scene, was regarded, like morphine before

it, and opium before morphine, as a "miracle drug" that had the ability to "kill all pain

and anger and bring relief to every sorrow." A single dose sends the average user into a

deep, euphoric reverie. Repeated use, however, creates an intense physical craving in the

human body chemistry and changes the average person into a slavish addict whose entire

existence revolves around his daily dosage. Sudden withdrawal can produce vomiting,

violent convulsions, or fatal respiratory failure. An overdose cripples the body's central

nervous system, plunges the victim into a, deep coma, and usually produces death within

a matter of minutes. Heroin addiction destroys man's normal social instincts, including

sexual desire, and turns the addict into a lone predator who willingly resorts to any crime burglary,

armed robbery, armed assault, prostitution, or shoplifting-for money to maintain

his habit. The average addict spends $8,000 a year on heroin, and experts believe that

New York State's addicts alone steal at least half a billion dollars annually to maintain their

habits. (6)

Heroin is a chemically bonded synthesis of acetic anhydride, a common industrial acid,

and morphine, a natural organic pain killer extracted from the opium poppy. Morphine is

the key ingredient. Its unique pharmaceutical properties are what make heroin so potent a

pain killer and such a dangerously addicting narcotic. The acidic bond simply fortifies the

morphine, making it at least ten times more powerful than ordinary medical morphine

and strengthening its addictive characteristics. Although almost every hospital in the

world uses some form of morphine as a post-operative pain killer, modern medicine

knows little more about its mysterious soothing properties than did the ancients who

discovered opium.

Scholars believe that man first discovered the opium poppy growing wild in mountains

bordering the eastern Mediterranean sometime in the Neolithic Age. Ancient medical

chronicles show that raw opium was highly regarded by early physicians hundreds of

years before the coming of Christ. It was known to Hippocrates in Greece and in Roman

times to the great physician Galen. From its original home in the eastern Mediterranean

region, opium spread westward through Europe in the Neolithic Age and eastward toward

India and China in the early centuries of the first millennium after Christ. Down through

the ages, opium continued to merit the admiration of physicians and gained in popularity;

in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century England, for example, opium-based medicines

were among the most popular drugstore remedies for such ordinary ailments as headaches

and the common cold.

Although physicians had used various forms of opium for three or four thousand years, it

was not until 1805 that medical science finally extracted pure morphine from raw opium.

Orally taken, morphine soon became an important medical anesthetic, but it was not until

1858 that two American doctors first experimented with the use of the hypodermic needle

to inject morphine directly into the bloodstream. (7) These discoveries were important

medical breakthroughs, and they greatly improved the quality of medical treatment in the

nineteenth century.

However, widespread use of morphine and opium-based medicines such as codeine soon

produced a serious drug addiction problem. In 1821 the English writer Thomas De

Quincey first drew attention to the problem of post-treatment addiction when he

published an essay entitled, Confessions of an English Opium Eater. De Quincey had

become addicted during his student days at Oxford University, and remained an addict

for the rest of his life. Finally recognizing the seriousness of the addiction problem,

medical science devoted considerable pharmacological research to finding a non addicting

pain killer,a search that eventually led to the discovery and popularization of heroin. In

1874 an English researcher, C. R. Wright, synthesized heroin, or diacetylmorphine, for

the first time when he boiled morphine and acetic anhydride over a stove for several

hours. After biological testing on dogs showed that diacetylmorphine induced "great

prostration, fear, sleepiness speedily following the administration and a slight tendency to

vomiting," the English researcher wisely decided to discontinue his experiments. (8) Less

than twenty years later, however, German scientists who tested diacetylmorphine

concluded that it was an excellent treatment for such respiratory ailments as bronchitis,

chronic coughing, asthma, and tuberculosis. Most importantly, these scientists claimed that diacetylmorphine was the ideal non addicting substitute for morphine and codeine.

Encouraged by these results, the Bayer chemical cartel of Elberfeld, Germany, decided to

manufacture diacetylmorphine and dreamed up the brand name "heroin" for its

mass marketing campaign. Bayer wanted all the world to know about its new pain

reliever, and in 1898 it launched an aggressive international advertising campaign in a

dozen different languages.(9)

(10)

Hailed as a

"miracle drug"

by medical

experts around

the globe,

heroin was

widely

prescribed as a

non addicting

cure-all for

whatever ails

you, and soon

became one of

the most

popular patent

medicines on

the market. The

drug's

popularity encouraged imitators, and a Saint Louis pharmaceutical company offered a

"Sample Box Free to Physicians" of its "Dissolve on the Tongue Antikamnia & Heroin

Tablets." (11) And in 1906 the American Medical Association (A.M.A) approved heroin

for general use and advised that it be used "in place of morphine in various painful

infections." (12)

Unrestricted distribution by physicians and pharmacies created an enormous drug abuse

problem; in 1924 federal narcotics officials estimated that there were 200,000 addicts in

the United States, (13) and the deputy police commissioner of New York reported that 94

percent of all drug addicts arrested for various crimes were heroin users.(14) The growing

dimensions of heroin addiction finally convinced authorities that heroin's liabilities

outweighed its medical merits, and in 1924 both houses of Congress unanimously passed

legislation outlawing the import or manufacture of heroin.(15)

After a quarter century of monumental heroin abuse, the international medical

community finally recognized the dangers of unrestricted heroin use, and the League of

Nations began to regulate and reduce the legal manufacture of heroin. The Geneva

Convention of 1925 imposed a set of strict regulations on the manufacture and export of heroin, and the Limitation Convention of 1931 stipulated that manufacturers could only

produce enough heroin to meet legitimate "medical and scientific needs." As a result of

these treaties, the world's total legal heroin production plummeted from its peak of nine

thousand kilograms (I kilo = 2.2 pounds) in 1926 to little more than one thousand kilos in

1931. (16)

However, the sharp decline in legal pharmaceutical output by no means put an end to

widespread heroin addiction. Aggressive criminal syndicates shifted the center of world

heroin production from legitimate pharmaceutical factories in Europe to clandestine

laboratories in Shanghai and Tientsin, China. (17) Owned and operated by a powerful

Chinese secret society, these laboratories started to supply vast quantities of illicit heroin

to corrupt Chinese warlords, European criminal syndicates, and American mafiosi like

Lucky Luciano. In Marseille, France, fledgling Corsican criminal syndicates opened up

smaller laboratories and began producing for European markets and export to the United

States.(18)

While law enforcement efforts failed to stem the flow of illicit heroin into the United

States during the 1930's, the outbreak of World War II seriously disrupted international

drug traffic. Wartime border security measures and a shortage of ordinary commercial

shipping made it nearly impossible for traffickers to smuggle heroin into the United

States. Distributors augmented dwindling supplies by "cutting" (adulterating) heroin with

increasingly greater proportions of sugar or quinine; while most packets of heroin sold in

the United States were 28 percent pure in 1938, only three years later they were less than

3 percent pure. As a result of all this, many American addicts were forced to undergo

involuntary withdrawal from their habits, and by the end of World War 11 the American

addict population had dropped to less than twenty thousand." (18) In fact, as the war drew

to a close, there was every reason to believe that the scourge of heroin had finally been

purged from the United States. Heroin supplies were nonexistent, international criminal

syndicates were in disarray, and the addict population was reduced to manageable

proportions for the first time in half a century.

But the disappearance of heroin addiction from the American scene was not to be. Within

several years, in large part thanks to the nature of U.S. foreign policy after World War II,

the drug syndicates were back in business, the poppy fields in Southeast Asia started to

expand and heroin refineries multiplied both in Marseilles and Hong Kong.(19) How did

we come to inflict this heroin plague on ourselves?

The answer lies in the history of America's cold war crusade. World War II shattered the

world order much of the globe had known for almost a century. Advancing and retreating

armies surged across the face of three continents, leaving in their wake a legacy of

crumbling empires, devastated national economies, and shattered social orders. In Europe

the defeat of Fascist regimes in Germany, Italy, France, and eastern Europe released

workers from years of police state repression. A wave of grass roots militancy swept

through European labor movements, and trade unions launched a series of spectacular

strikes to achieve their economic and political goals. Bled white by six years of costly

warfare, both the victor and vanquished nations of Europe lacked the means and the will to hold on to their Asian colonial empires. Within a few years after the end of World War

II, vigorous national liberation movements swept through Asia from India to Indonesia as

indigenous groups rose up against their colonial masters.

America's nascent cold war crusaders viewed these events with undisguised horror

Conservative Republican and Democratic leaders alike felt that the United States should

be rewarded for its wartime sacrifices. These men wanted to inherit the world as it had

been and had little interest in seeing it changed. Henry Luce, founder of the Time-Life

empire, argued that America was the rightful heir to Great Britain's international primacy

and heralded the postwar era as "The American Century." To justify their "entanglement

in foreign adventures," America's cold warriors embraced a militantly anti-Communist

ideology. In their minds the entire world was locked in a Manichaean struggle between

"godless communism" and "the free world." The Soviet Union was determined to

conquer the world, and its leader, Joseph Stalin, was the new Hitler. European labor

movements and Asian nationalist struggles were pawns of "international communism,"

and as such had to be subverted or destroyed. There could be no compromise with this

monolithic evil: negotiations were "appeasement" and neutralism was "im moral." In this

desperate struggle to save "Western civilization," any ally was welcome and any means

was justified. The military dictatorship on Taiwan became "free China"; the police state

in South Vietnam was "free Vietnam"; a collection of military dictatorships stretching

from Pakistan to Argentina was "the free world." The CIA became the vanguard of

America's anti-Communist crusade, and it dispatched small numbers of well-financed

agents to every corner of the globe to mold local political situations in a fashion

compatible with American interests. Practicing a ruthless form of clandestine realpolitik,

its agents made alliances with any local group willing and able to stem the flow of

"Communist aggression." Although these alliances represent only a small fraction of CIA

postwar operations, they have nevertheless had a profound impact on the international

heroin trade.

The cold war was waged in many parts of the world, but Europe was the most important

battleground in the 1940's and 1950's. Determined to restrict Soviet influence in western

Europe, American clandestine operatives intervened in the internal politics of Germany,

Italy, and France. In Sicily, the forerunner of the CIA, the Office of Strategic Services

(O.S.S), formed an alliance with the Sicilian Mafia to limit the political gains of the Italian

Communist party on this impoverished island. In France the Mediterranean port city of Marseilles became a major battleground between the CIA and the French Communist

party during the late 1940's. To tip the balance of power in its favor, the CIA recruited

Corsican gangsters to battle Communist strikers and backed leading figures in the city's

Corsican underworld who were at odds with the local Communists. Ironically, both the

Sicilian Mafia and the Corsican underworld played a key role in the growth of Europe's

postwar heroin traffic and were to provide most of the heroin smuggled into the United

States for the next two decades.

However, the mid-1960's marked the peak of the European heroin industry, and shortly

thereafter it went into a sudden decline. In the early 1960's the Italian government

launched a crackdown on the Sicilian Mafia, and in 1967 the Turkish government announced that it would begin phasing out cultivation of opium poppies on the Anatolian

plateau in order to deprive Marseilles's illicit heroin laboratories of their most important

source of raw material. Unwilling to abandon their profitable narcotics racket, the

American Mafia and Corsican syndicates shifted their sources of supply to Southeast

Asia, where surplus opium production and systematic government corruption created an

ideal climate for large-scale heroin production.

And once again American foreign policy played a role in creating these favorable

conditions. During the early 1950's the CIA had backed the formation of a Nationalist

Chinese guerrilla army in Burma, which still controls almost a third of the world's illicit

opium supply, and in Laos the CIA created a Meo mercenary army whose commander

manufactured heroin for sale to Americans G.I's in South Vietnam. The State Department

provided unconditional support for corrupt governments openly engaged in the drug

traffic. In late 1969 new heroin laboratories sprang up in the tri-border area where Burma,

Thailand, and Laos converge, and unprecedented quantities of heroin started flooding

into the United States. Fueled by these seemingly limitless supplies of heroin, America's

total number of addicts skyrocketed.

Unlike some national intelligence agencies, the CIA did not dabble in the drug traffic to

finance its clandestine operations. Nor was its culpability the work of a few corrupt

agents, eager to share in the enormous profits. The CIA's role in the heroin traffic was

simply an inadvertent but inevitable consequence of its cold war tactics.[I do not buy that for a second,it might have started like that,but the agencies continued involvement in drug trafficking in heroin as well as cocaine, and the stories of the corrupt banks laundering big time $$$,indicates that by 2017 it has become about the money DC]

The Logistics of Heroin

America's heroin addicts are victims of the most profitable criminal enterprise known to

man,an enterprise that involves millions of peasant farmers in the mountains of Asia,

thousands of corrupt government officials, disciplined criminal syndicates, and agencies

of the United States government. America's heroin addicts are the final link in a chain of

secret criminal transactions that begin in the opium fields of Asia, pass through

clandestine heroin laboratories in Europe and Asia, and enter the United States through a

maze of international smuggling routes.

Almost all of the world's illicit opium is grown in a narrow band of mountains that

stretches along the southern rim of the great Asian land mass, from Turkey's and

Anatolian plateau, through the northern reaches of the Indian subcontinent, all the way to

the rugged mountains of northern Laos. Within this 4,500-mile stretch of mountain

landscape, peasants and tribesmen of eight different nations harvest some fourteen

hundred tons a year of raw opium, which eventually reaches the world's heroin and

opium addicts." A small percentage of this fourteen hundred tons is diverted from

legitimate pharmaceutical production in Turkey, Iran, and India, but most of it is grown

expressly for the international narcotics traffic in South and Southeast Asia. Although

Turkey was the major source of American narcotics through the 1960's, the hundred tons

of raw opium its licensed peasant farmers diverted from legitimate production never

accounted for more than 7 percent of the world's illicit supply. (20) About 24 percent is harvested by poppy farmers in South Asia (Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India). However,

most of this is consumed by local opium addicts, and only insignificant quantities find

their way to Europe or the United States. (21) It is Southeast Asia that has become the

world's most important source of illicit opium. Every year the hill tribe farmers of

Southeast Asia's Golden Triangle region-northeastern Burma, northern Thailand, and

northern Laos-harvest approximately one thousand tons of raw opium, or about 70

percent of the world's illicit supply. (22)

Despite countless minor variations, all of Asia's poppy farmers use the same basic

techniques when they cultivate the opium poppy. The annual crop cycle begins in late

summer or early fall as the farmers scatter handfuls of tiny poppy seeds across the surface

of their hoed fields. At maturity the greenish-colored poppy plant has one main tubular

stem, which stands about three or four feet high, and perhaps half a dozen to a dozen

smaller stems. About three months after planting, each stem produces a brightly colored

flower; gradually the petals drop to the ground, exposing a green seed pod about the size

and shape of a bird's egg. For reasons still unexplained by botanists, the seed pod

synthesizes a milky white sap soon after the petals have fallen away. This sap is opium,

and the farmers harvest it by cutting a series of shallow parallel incisions across the bulb's

surface with a special curved knife. As the white sap seeps out of the incisions and

congeals on the bulb's surface, it changes to a brownish-black color. The farmer collects

the opium by scraping off the bulb with a flat, dull knife.

Even in this age of jumbo jets and supersonic transports, raw opium still moves from the

poppy fields to the morphine refineries on horseback. There are few roads in these

underdeveloped mountain regions, and even where there are, smugglers generally prefer

to stick to the mountain trails where there are fewer police. Most traffickers prefer to do

their morphine refining close to the poppy fields, since compact morphine bricks are

much easier to smuggle than bundles of pungent, jellylike opium. Although they are

separated by over four thousand miles, criminal "chemists" of the Middle East and

Southeast Asia use roughly the same technique to extract pure morphine from opium. The

chemist begins the process by heating water in an oil drum over a wood fire until his

experienced index finger tells him that the temperature is just right. Next, raw opium is

dumped into the drum and stirred with a heavy stick until it dissolves. At the propitious

moment the chemist adds ordinary lime fertilizer to the steaming solution, precipitating

out organic waste and leaving the morphine suspended in the chalky white water near the

surface. While filtering the water through an ordinary piece of flannel cloth to remove

any residual waste matter, the chemist pours the solution into another oil drum. As the

solution is heated and stirred a second time, concentrated ammonia is added, causing the

morphine to solidify and drop to the bottom. Once more the solution is filtered through

flannel, leaving chunky white kernels of morphine on the cloth. Once dried and packaged

for shipment, the morphine usually weighs about 10 percent of what the raw opium from

which it was extracted weighed. (23)

The heroin manufacturing process is a good deal more complicated, and requires the

supervision of an expert chemist. Since the end of World War II, Marseilles and Hong

Kong have established themselves as the major centers for heroin laboratories. However,

their dominance is now being challenged by a new cluster of heroin laboratories located

in the wilds of Southeast Asia's Golden Triangle. Most laboratories are staffed by a three man

team consisting of an experienced "master chemist" and two apprentices. In most

cases the master chemist is really a "master chef" who has simply memorized the

complicated five-part recipe after several years as an assistant. The goal of the five-stage

process is to chemically bind morphine molecules with acetic acid and then process the

compound to produce a fluffy white powder that can be injected from a syringe,

STAGE ONE. To produce ten kilos of pure heroin (the normal daily output of many labs),

the chemist heats ten kilos of morphine and ten kilos of acetic anhydride in an enamel bin

or glass flask. After being heated six hours at exactly 185' F., the morphine and acid

become chemically bonded, creating an impure form of diacetylmorphine (heroin).

STAGE TWO . To remove impurities from the compound, the solution is treated with water

and chloroform until the impurities precipitate out, leaving a somewhat higher grade of

diacetylmorphine.

STAGE THREE. The solution is drained off into another container, and sodium carbonate

is added until the crude heroin particles begin to solidify and drop to the bottom.

STAGE FOUR. After the heroin particles are filtered out of the sodium carbonate solution

under pressure by a small suction pump, they are purified in a solution of alcohol and

activated charcoal. The new mixture is heated until the alcohol begins to evaporate,

leaving relatively pure granules of heroin at the bottom of the flask.

STAGE FIVE. This final stage produces the fine white powder prized by American

addicts, and requires considerable skill on the part of an underworld chemist. The heroin

is placed in a large flask and dissolved in alcohol. As ether and hydrochloric acid are

added to the solution, tiny white flakes begin to form. After the flakes are filtered out

under pressure and dried through a special process, the end result is a white powder, 80 to

99 percent pure, known as "no. 4 heroin." In the hands of a careless chemist the volatile

ether gas may ignite and produce a violent explosion that could level the clandestine

laboratory.(24)

Once it is packaged in plastic envelopes, heroin is ready for its trip to the United States.

An infinite variety of couriers and schemes are used to smuggle stewardesses, Filipino

diplomats, businessmen, Marseilles pimps, and even Playboy playmates. But regardless of

the means used to smuggle, almost all of these shipments are financed and organized by

one of the American Mafia's twenty-four regional groups, or "families." Although the top

bosses of organized crime never even see, much less touch, the heroin, their vast financial

resources and their connections with Chinese syndicates in Hong Kong and Corsican

gangs in Marseilles and Indochina play a key role in the importation of America's heroin

supply. The top bosses usually deal in bulk shipments of twenty to a hundred kilos of no. 4 heroin, for which they have to advance up to $27,000 per kilo in cash. After a shipment

arrives, the bosses divide it into wholesale lots of one to ten kilos for sale to their

underlings in the organized crime families. A lower-ranking mafioso, known as a "kilo

connection" in the trade, dilutes the heroin by 50 percent and breaks it into smaller lots,

which he turns over to two or three distributors. From there the process of dilution and

profit making continues downward through another three levels in the distribution

network until it finally reaches the street.25 By this time the heroin's value has increased

tenfold to $225,000 a kilo, and it is so heavily diluted that the average street packet sold

to an addict is less than 5 percent pure.

To an average American who witnesses the daily horror of the narcotics traffic at the

street level, it must seem inconceivable that his government could be in any way

implicated in the international narcotics traffic. The media have tended to reinforce this

outlook by depicting the international heroin traffic as a medieval morality play: the

traffickers are portrayed as the basest criminals, continually on the run from the minions

of law and order; and American diplomats and law enforcement personnel are depicted as

modern-day knight servant staunchly committed to the total, immediate eradication of

heroin trafficking. Unfortunately, the characters in this drama cannot be so easily

stereotyped. American diplomats and secret agents have been involved in the narcotics

traffic at three levels: (1) coincidental complicity by allying with groups actively engaged

in the drug traffic; (2) abetting the traffic by covering up for known heroin traffickers and

condoning their involvement; (3) and active engagement in the transport of opium and

heroin. It is ironic, to say the least, that America's heroin plague is of its own making.

1.

Sicily: Home of the Mafia

AT THE END of World War II, there was an excellent chance that heroin addiction could

be eliminated in the United States. The wartime security measures designed to prevent

infiltration of foreign spies and sabotage to naval installations made smuggling into the

United States virtually impossible. Most American addicts were forced to break their

habits during the war, and consumer demand just about disappeared. Moreover, the

international narcotics syndicates were weakened by the war and could have been

decimated with a minimum of police effort. (1)

During the 1930's most of America's heroin had come from China's refineries centered in

Shanghai and Tientsin. This was supplemented by the smaller amounts produced in Marseilles by the Corsican syndicates and in the Middle East by the notorious Eliopoulos

brothers. Mediterranean shipping routes were disrupted by submarine warfare during the

war, and the Japanese invasion of China interrupted the flow of shipments to the United

States from the Shanghai and Tientsin heroin laboratories. The last major wartime seizure

took place in 1940, when forty-two kilograms of Shanghai heroin were discovered in San

Francisco. During the war only tiny quantities of heroin were confiscated, and laboratory

analysis by federal officials showed that its quality was constantly declining; by the end

of the war most heroin was a crude Mexican product, less than 3 percent pure. And a surprisingly high percentage of the samples were fake.' As has already been mentioned,

most addicts were forced to undergo an involuntary withdrawal from heroin, and at the

end of the war the Federal Bureau of Narcotics reported that there were only 20,000

addicts in all of America. (2)

After the war, Chinese traffickers had barely reestablished their heroin labs when Mao

Tse-tung's peasant armies captured Shanghai and drove them out of China. (3) The

Eliopoulos brothers had retired from the trade with the advent of the war, and a postwar

narcotics indictment in New York served to discourage any thoughts they may have had

of returning to it. (4) The hold of the Corsican syndicates in Marseilles was weakened,

since their most powerful leaders had made the tactical error of collaborating with the

Nazi Gestapo, and so were either dead or in exile. Most significantly, Sicily's Mafia had

been smashed almost beyond repair by two decades of Mussolini's police repression. It

was barely holding onto its control of local protection money from farmers and

shepherds. (5)

With American consumer demand reduced to its lowest point in fifty years and the

international syndicates in disarray, the U.S. government had a unique opportunity to

eliminate heroin addiction as a major American social problem. However, instead of

delivering the death blow to these criminal syndicates, the U.S. government-through the

Central Intelligence Agency and its wartime predecessor, the O.S.S-created a situation that

made it possible for the Sicilian/American Mafia and the Corsican underworld to revive

the international narcotics traffic.(6)

In Sicily the O.S.S initially allied with the Mafia to assist the Allied forces in their 1943

invasion. Later, the alliance was maintained in order to check the growing strength of the

Italian Communist party on the island. In Marseilles the CIA joined forces with the

Corsican underworld to break the hold of the Communist Party over city government and

to end two dock strikes--one in 1947 and the other in 1950-that threatened efficient

operation of the Marshall Plan and the First Indochina War. (7) Once the United States

released the Mafia's corporate genius, Lucky Luciano, as a reward for his wartime

services, the international drug trafficking syndicates were back in business within an

alarmingly short period of time. And their biggest customer? The United States, the

richest nation in the world, the only one of the great powers that had come through the

horrors of World War II relatively untouched, and the country that had the biggest

potential for narcotics distribution. For, in spite of their forced withdrawal during the war

years, America's addicts could easily be won back to their heroin persuasion. For

America itself had long had a drug problem, one that dated back to the nineteenth century.

Addiction in America:

The Root of the Problem

Long before opium and heroin addiction became a law enforcement problem, it was a

major cause for social concern in the United States. By the late 1800's Americans were

taking opium-based drugs with the same alarming frequency as they now consume tranquilizers, pain killers, and diet pills. Even popular children's medicines were

frequently opium based. When heroin was introduced into the United States by the

German pharmaceutical company, Bayer, in 1898, it was, as has already been mentioned,

declared nonaddictive, and was widely prescribed in hospitals and by private practitioners

as a safe substitute for morphine. After opium smoking was outlawed in the United States

ten years later, many opium addicts turned to heroin as a legal substitute, and America's

heroin problem was born,

By the beginning of World War I the most conservative estimate of America's addict

population was 200,000, and growing alarm over the uncontrolled use of narcotics

resulted in the first attempts at control. In 1914 Congress passed the Harrison Narcotics

Act. It turned out to be a rather ambiguous statute, requiring only the registration of all

those handling opium and coca products and establishing a stamp tax of one cent an

ounce on these drugs. A medical doctor was allowed to prescribe opium, morphine, or

heroin to a patient, "in the course of his professional practice only." The law, combined

with public awareness of the plight of returning World War I veterans who had become

addicted to medical morphine, resulted in the opening of hundreds of public drug

maintenance clinics. Most clinics tried to cure the addict by gradually reducing his intake

of heroin and morphine. However, in 1923 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled, in United

States vs. Behrman, that the Harrison Act made it illegal for a medical doctor to

prescribe morphine or heroin to an addict under any circumstances. The clinics shut their

doors and a new figure appeared on the American scene-the pusher.

The Mafia in America

At first the American Mafia ignored this new business opportunity.[yeah until the Jews got involved DC] Steeped in the

traditions of the Sicilian "honored society," which absolutely forbade involvement in

either narcotics or prostitution, the Mafia left the heroin business to the powerful Jewish

gangsters-such as "Legs" Diamond, "Dutch" Schultz, and Meyer Lansky-who dominated

organized crime in the 1920's. The Mafia contented itself with the substantial profits to be

gained from controlling the bootleg liquor industry.(8)However, in 1930-1931, only

seven years after heroin was legally banned, a war erupted in the Mafia ranks. Out of the

violence that left more than sixty gangsters dead came a new generation of leaders with

little respect for the traditional code of honor."

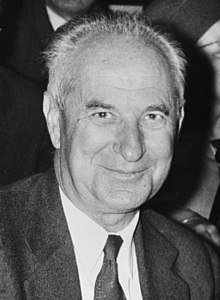

Salvatore

Lucania, alias

Lucky Luciano.

The leader of this

mafioso youth

movement was the

legendary

Salvatore C.

Luciana, known to

the world as

Charles "Lucky"

Luciano.

Charming and

strikingly

handsome,

Luciano must rank

as one of the most

brilliant criminal

executives of the

modern age. For,

at a series of

meetings shortly

following the last

of the bloodbaths

that completely

eliminated the old

guard, Luciano

outlined his plans

for a modern,

nationwide crime

cartel. His modernization scheme quickly won total support from the leaders of America's

twenty-four Mafia "families," and within a few months the National Commission was

functioning smoothly. This was an event of historic proportions: almost singlehanded,

Luciano built the Mafia into the most powerful criminal syndicate in the United States

and pioneered organizational techniques that are still the basis of organized crime today.

Luciano also forged an alliance between the Mafia and Meyer Lansky's Jewish gangs that

has survived for almost 40 years and even today is the dominant characteristic of

organized crime in the United States.

With the end of Prohibition in sight, Luciano made the decision to take the Mafia into the

lucrative prostitution and heroin rackets. This decision was determined more by financial

considerations than anything else. The predominance of the Mafia over its Jewish and

Irish rivals had been built on its success in illegal distilling and rum running. Its continued

preeminence, which Luciano hoped to maintain through superior organization, could only

be sustained by developing new sources of income.

Heroin was an attractive substitute because its relatively recent prohibition had left a

large market that could be exploited and expanded easily. Although heroin addicts in no

way compared with drinkers in numbers, heroin profits could be just as substantial:

heroin's light weight made it less expensive to smuggle than liquor, and its relatively

limited number of sources made it more easy to monopolize.

Heroin, moreover, complemented Luciano's other new business venture-the organization

of prostitution on an unprecedented scale. Luciano forced many small-time pimps out of

business as he found that addicting his prostitute labor force to heroin kept them

quiescent, steady workers, with a habit to support and only one way to gain enough

money to support it. This combination of organized prostitution and drug addiction,

which later became so commonplace, was Luciano's trademark in the 1930's. By 1935 he

controlled 200 New York City brothels with twelve hundred prostitutes, providing him

with an estimated income of more than $10 million a year. (9) Supplemented by growing

profits from gambling and the labor movement (gangsters seemed to find a good deal of

work as strikebreakers during the depression years of the 1930's) as well, organized crime

was once again on a secure financial footing.

But in the late 1930's the American Mafia fell on hard times. Federal and state

investigators launched a major crackdown on organized crime that produced one

spectacular narcotics conviction and forced a number of powerful mafiosi to flee the

country. In 1936 Thomas Dewey's organized crime investigators indicted Luciano

himself on sixty-two counts of forced prostitution. Although the Federal Bureau of

Narcotics had gathered enough evidence on Luciano's involvement in the drug traffic to

indict him on a narcotics charge, both the bureau and Dewey's investigators felt that the

forced prostitution charge would be more likely to offend public sensibilities and secure a

conviction. They were right. While Luciano's modernization of the profession had

resulted in greater profits, he had lost control over his employees, and three of his

prostitutes testified against him. The New York courts awarded him a thirty to fifty-year

jail term. (10)

Luciano's arrest and conviction was a major setback for organized crime: it removed the

underworld's most influential mediator from active leadership and probably represented a

severe psychological shock for lower-ranking gangsters.

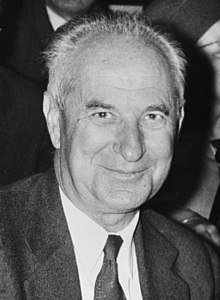

Cesare Mori(L)

However, the Mafia suffered even more severe shocks on the mother island of Sicily.

Although Dewey's reputation as a "racket-busting" district attorney was rewarded by a

governorship and later by a presidential nomination, his efforts seem feeble indeed

compared to Mussolini's personal vendetta against the Sicilian Mafia. During a state visit

to a small town in western Sicily in 1924, the Italian dictator offended a local Mafia boss

by treating him with the same condescension he usually reserved for minor municipal

officials. The mafioso made the foolish mistake of retaliating by emptying the piazza of

everyone but twenty beggars during Mussolini's speech to the "assembled populace."(11)

Upon his return to Rome, the outraged Mussolini appeared before the Fascist parliament

and declared total war on the Mafia. Cesare Mori was appointed prefect of Palermo and

for two years conducted a reign of terror in western Sicily that surpassed even the Holy Inquisition. Combining traditional torture with the most modern innovations, Mori

secured confessions and long prison sentences for thousands of mafiosi and succeeded in

reducing the venerable society to its weakest state in a hundred years."(12) Although the

campaign ended officially in 1927 as Mori accepted the accolades of the Fascist

parliament, local Fascist officials continued to harass the Mafia. By the beginning of

World War II, the Mafia had been driven out of the cities and was surviving only in the

mountain areas of western Sicily.(13)

The Mafia Restored: Fighters

for Democracy in World War II

World War II gave the Mafia a new lease on life. In the United States, the Office of

Naval Intelligence (O.N.I) became increasingly concerned over a series of sabotage

incidents on the New York waterfront, which culminated with the burning of the French

liner Normandie on the eve of its christening as an Allied troop ship.

Joseph Lanza

Powerless to infiltrate the waterfront itself, the O.N.I very practically decided to fight fire

with fire, and contacted Joseph Lanza, Mafia boss of the East Side docks, who agreed to

organize effective anti sabotage surveillance throughout his waterfront territory. When

O.N.I decided to expand "Operation Underworld" to the West Side docks in 1943 they

discovered they would have to deal with the man who controlled them: Lucky Luciano,

unhappily languishing in the harsh Dannemora prison. After he promised full cooperation

to naval intelligence officers, Luciano was rewarded by being transferred to a less austere

state penitentiary near Albany, where he was regularly visited by military officers and

underworld leaders such as Meyer Lansky (who had emerged as Luciano's chief

assistant). (14)

While O.N.I enabled Luciano to resume active leadership of American organized crime,

the Allied invasion of Italy returned the Sicilian Mafia to power.

On the night of July 9, 1943, 160,000 Allied troops landed on the extreme southwestern

shore of Sicily.(15) After securing a beachhead, Gen. George Patton's U.S. Seventh Army

launched an offensive into the island's western hills, Italy's Mafia land, and headed for the

city of Palermo. (16) Although there were over sixty thousand Italian troops and a

hundred miles of booby trapped roads between Patton and Palermo, his troops covered the

distance in a remarkable four days.(17)

The Defense Department has never offered any explanation for the remarkable lack of

resistance in Patton's race through western Sicily and pointedly refused to provide any

information to Sen. Estes Kefauver's Organized Crime Subcommittee in 1951.(18)

However, Italian experts on the Sicilian Mafia have never been so reticent.

Five days after the Allies landed in Sicily an American fighter plane flew over the village

of Villalba, about forty-five miles north of General Patton's beachhead on the road to

Palermo, and jettisoned a canvas sack addressed to "Zu Calo." "Zu Calo," better known

as Don Calogero Vizzini, was the unchallenged leader of the Sicilian Mafia and lord of the mountain region through which the American army would be passing. The sack

contained a yellow silk scarf emblazoned with a large black L. The L, of course, stood for

Lucky Luciano, and silk scarves were a common form of identification used by mafiosi

traveling from Sicily to America. (19)

Don Calogero

It was hardly surprising that Lucky Luciano should be communicating with Don

Calogero under such circumstances; Luciano had been born less than fifteen miles from

Villalba in Lercara Fridi, where his mafiosi relatives still worked for Don Calogero. (20)

Two days later, three American tanks rolled into Villalba after driving thirty miles

through enemy territory. Don Calogero climbed aboard and spent the next six days

traveling through western Sicily organizing support for the advancing American troops.

(21) As General Patton's Third Division moved onward into Don Calogero's mountain

domain, the signs of its dependence on Mafia support were obvious to the local

population. The Mafia protected the roads from snipers, arranged enthusiastic welcomes

for the advancing troops, and provided guides through the confusing mountain terrain.

(22)

While the role of the Mafia is little more than a historical footnote to the Allied conquest

of Sicily, its cooperation with the American military occupation (AMGOT) was

extremely important. Although there is room for speculation about Luciano's precise role

in the invasion, there can be little doubt about the relationship between the Mafia and the

American military occupation.

This alliance developed when, in the summer of 1943, the Allied occupation's primary

concern was to release as many of their troops as possible from garrison duties on the

island so they could be used in the offensive through southern Italy. Practicality was the

order of the day, and in October the Pentagon advised occupation officers "that the

carabinieri and Italian Army will be found satisfactory for local security purposes. (23)

But the Fascist army had long since deserted, and Don Calogero's Mafia seemed far more

reliable at guaranteeing public order than Mussolini's powerless carabinieri. So, in July

the Civil Affairs Control Office of the U.S. army appointed Don Calogero mayor of

Villalba. In addition, ANIGOT appointed loyal mafiosi as mayors in many of the towns

and villages in western Sicily. (24)

As Allied forces crawled north through the Italian mainland, American intelligence

officers became increasingly upset about the leftward drift of Italian politics. Between

late 1943 and mid 1944, the Italian Communist party's membership had doubled, and in

the German-occupied northern half of the country an extremely radical resistance

movement was gathering strength; in the winter of 1944, over 500,000 Turin workers

shut the factories for eight days despite brutal Gestapo repression, and the Italian

underground grew to almost 150,000 armed men. Rather than being heartened by the

underground's growing strength, the U.S. army became increasingly concerned about its

radical politics and began to cut back its arms drops to the resistance in mid 1944. (25)

"More than twenty years ago," Allied military commanders reported in 1944, "a similar

situation provoked the March on Rome and gave birth to Fascism. We must make up our minds-and that quickly-whether we want this second march developing into another 'ism.'

(26)

In Sicily the decision had already been made. To combat expected Communist gains,

occupation authorities used Mafia officials in the AMGOT administration. Since any

changes in the island's feudal social structure would cost the Mafia money and power, the

"honored society" was a natural anti-Communist ally. So confident was Don Calogero of

his importance to AMGOT that he killed Villalba's overly inquisitive police chief to free

himself of all restraints. (27) In Naples, one of Luciano's lieutenants, Vito Genovese, was

appointed to a position of interpreterliaison officer in American army headquarters and

quickly became one of AMGOT's most trusted employees. It was a remarkable turnabout;

less than a year before, Genovese had arranged the murder of Carlo Tresca, editor of an

anti-Fascist Italian-language newspaper in New York, to please the Mussolini

government. (28)

Carlo

Tresca (1879-1943), was born in Italy in 1879. After being active in the Italian

Railroad Workers' Federation, Tresca moved to the United States in 1904. Elected

secretary of the Italian Socialist Federation of North America and a member of the

Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), he took part in strikes of Pennsylvania

coal miners before becoming involved in the important industrial disputes in

Lawrence and Paterson. Tresca, who lived with

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, was editor of the antifascist

newspaper, Il Martello (The Hammer) for

over 20 years. Carlo Tresco was leader of the AntiFascist

Alliance and was assassinated in New York

City in 1943. Many of Tresca's comrades believed

that his murder had been ordered by Generoso

Pope, the ex-fascist publisher of Il Progresso ItaloAmericano,

as Tresca had attacked him

relentlessly throughout the 1930s and early 1940s.

One plausible theory said that Tresca was killed at

the order of an Italian underworld figure named

Frank Garofalo, identified as a member of the

Mafia. Another theory said that Carmine Galante

was the man who undoubtedly killed him. Galante

was to become one of the most significant figures in

a criminal group that has operated in New York,

and beyond, for seventy years. On that dark,

miserable January night when he gunned down his

target, the probable killer Galante was already

associated with or indeed possibly a member of a

Mafia organization that is known today as the

Bonanno Crime Family. (More Information)

Image: Vito Genovese (rigth) with Salvatore Giuliano (left). Genovese was Colonel

Poletti's driver, interpreter and consiglieri (adviser).

Genovese and Don Calogero were old friends, and they used their official positions to

establish one of the largest black market operations in all of southern Italy. Don Calogero

sent enormous truck caravans loaded with all the basic food commodities necessary for

the Italian diet rolling northward to hungry Naples, where their cargoes were distributed

by Genovese's organization (29) All of the trucks were issued passes and export papers

by the AMGOT administration in Naples and Sicily, and some corrupt American army

officers even made contributions of gasoline and trucks to the operation.

In exchange for these favors, Don Calogero became one of the major supporters of the

Sicilian Independence Movement, which was enjoying the covert support of the O.S.S. As

Italy veered to the left in 1943-1944, the American military became alarmed about their

future position in Italy and felt that the island's naval bases and strategic location in the

Mediterranean might provide a possible future counterbalance to a Communist mainland.

(30) Don Calogero supported this separatist movement by recruiting most of western

Sicily's mountain bandits for its volunteer army, but quietly abandoned it shortly after the

O.S.S dropped it in 1945.

Don Calogero rendered other services to the anti-Communist effort by breaking up leftist

political rallies. On September 16, 1944, for example, the Communist leader Girolama Li Causi held a rally in Villalba that ended abruptly in a hail of gunfire as Don Calogero's

men fired into the crowd and wounded nineteen spectators. (31) Michele Pantaleone, who

observed the Mafia's revival in his native village of Villalba, described the consequences

of AMGOT's occupation policies:

By the beginning of the Second World War, the Mafia was restricted to a few isolated

and scattered groups and could have been completely wiped out if the social problems of

the island had been dealt with . . . the Allied occupation and the subsequent slow

restoration of democracy reinstated the Mafia with its full powers, put it once more on the

way to becoming a political force, and returned to the Onorata Societa the weapons

which Fascism had snatched from it. (32)

Luciano Organizes the

Postwar Heroin Trade

In 1946 American military intelligence made one final gift to the Mafia -they released

Luciano from prison and deported him to Italy, thereby freeing the greatest criminal

talent of his generation to rebuild the heroin trade. Appealing to the New York State

Parole Board in 1945 for his immediate release, Luciano's lawyers based their case on his

wartime services to the navy and army. Although naval intelligence officers called to give

evidence at the hearings were extremely vague about what they had promised Luciano in

exchange for his services, one naval officer wrote a number of confidential letters on

Luciano's behalf that were instrumental in securing his release. (33) Within two years

after Luciano returned to Italy, the U.S. government deported over one hundred more

mafiosi as well. And with the cooperation of his old friend, Don Calogero, and the help

of many of his old followers from New York, Luciano was able to build an awesome

international narcotics syndicate soon after his arrival in Italy. (34)

The narcotics syndicate Luciano organized after World War It remains one of the most

remarkable in the history of the traffic. For more than a decade it moved morphine base

from the Middle East to Europe, transformed it into heroin, and then exported it in

substantial quantities to the United States-all without ever suffering a major arrest or

seizure. The organization's comprehensive distribution network within the United States

increased the number of active addicts from an estimated 20,000 at the close of the war to

60,000 in 1952 and to 150,000 by 1965.

After resurrecting the narcotics traffic, Luciano's first problem was securing a reliable

supply of heroin. Initially he relied on diverting legally produced heroin from one of

Italy's most respected pharmaceutical companies, Schiaparelli. However, investigations

by the U.S. Federal Bureau of Narcotics in 1950-which disclosed that a minimum of 700

kilos of heroin had been diverted to Luciano over a four-year period-led to a tightening of

Italian pharmaceutical regulations. (35) But by this time Luciano had built up a network

of clandestine laboratories in Sicily and Marseilles and no longer needed to divert the

Schiaparelli product.

Morphine base was now the necessary commodity. Thanks to his contacts in the Middle

East, Luciano established a long-term business relationship with a Lebanese who was

quickly becoming known as the Middle East's major exporter of morphine base,Sami El

Khoury. Through judicious use of bribes and his high social standing in Beirut society,

(36) El Khoury established an organization of unparalleled political strength. The

directors of Beirut Airport, Lebanese customs, the Lebanese narcotics police, and perhaps

most importantly, the chief of the anti subversive section of the Lebanese police, (37)

protected the import of raw opium from Turkey's Anatolian plateau into Lebanon, its

processing into morphine base, and its final export to the laboratories in Sicily and Marseilles. (38)

After the morphine left Lebanon, its first stop was the bays and inlets of Sicily's western

coast. There Palermo's fishing trawlers would meet ocean-going freighters from the

Middle East in international waters, pick up the drug cargo, and then smuggle it into

fishing villages scattered along the rugged coastline. (39)

Once the morphine base was safely ashore, it was transformed into heroin in one of

Luciano's clandestine laboratories. Typical of these was the candy factory opened in

Palermo in 1949: it was leased to one of Luciano's cousins and managed by Don

Calogero himself.(40) The laboratory operated without incident until April 11, 1954,

when the Roman daily Avanti! published a photograph of the factory under the headline

"Textiles and Sweets on the Drug Route." That evening the factory was closed, and the

laboratory's chemists were reportedly smuggled out of the country. (41)

Once heroin had been manufactured and packaged for export, Luciano used his Mafia

connections to send it through a maze of international routes to the United States. Not all

of the mafiosi deported from the United States stayed in Sicily. To reduce the chance of

seizure, Luciano had placed many of them in such European cities as Milan, Hamburg,

Paris, and Marseilles so they could forward the heroin to the United States after it arrived

from Sicily concealed in fruits, vegetables, or candy. From Europe heroin was shipped

directly to New York or smuggled through Canada and Cuba. (42)

While Luciano's prestige and organizational genius were an invaluable asset, a large part

of his success was due to his ability to pick reliable subordinates. After he was deported

from the United States in 1946, he charged his long-time associate, Meyer Lansky, with

the responsibility for managing his financial empire. Lansky also played a key role in

organizing Luciano's heroin syndicate: he supervised smuggling operations, negotiated

with Corsican heroin manufacturers, and managed the collection and concealment of the

enormous profits. Lansky's control over the Caribbean and his relationship with the

Florida-based Trafficante family were of particular importance, since many of the heroin

shipments passed through Cuba or Florida on their way to America's urban markets. For

almost twenty years the Luciano-Lansky-Trafficante troika remained a major feature of

the international heroin traffic. (43)

Organized crime was welcome in pre-revolutionary Cuba, and Havana was probably the

most important transit point for Luciano's European heroin shipments. The leaders of Luciano's heroin syndicate were at home in the Cuban capital, and regarded it as a "safe"

city: Lansky owned most of the city's casinos, and the Trafficante family served as

Lansky's resident managers in Havana. (44)

Luciano's 1947 visit to Cuba laid the groundwork for Havana's subsequent role in

international narcotics-smuggling traffic. Arriving in January, Luciano summoned the

leaders of American organized crime, including Meyer Lansky, to Havana for a meeting,

and began paying extravagant bribes to prominent Cuban officials as well. The director of

the Federal Bureau of Narcotics at the time felt that Luciano's presence in Cuba was an

ominous sign.

I had received a preliminary report through a Spanish-speaking agent I had sent to

Havana, and I read this to the Cuban Ambassador. The report stated that Luciano had

already become friendly with a number of high Cuban officials through the lavish use of

expensive gifts. Luciano had developed a full-fledged plan which envisioned the

Caribbean as his center of operations . . . Cuba was to be made the center of all inter

national narcotic operations. (45)

Pressure from the United States finally resulted in the revocation of Luciano's residence

visa and his return to Italy, but not before he bad received commitments from organized

crime leaders in the United States to distribute the regular heroin -shipments he promised

them from Europe. (46)

The Caribbean, on the whole, was a happy place for American racketeers-most

governments were friendly and did not interfere with the "business ventures" that brought

some badly needed capital into their generally poor countries. Organized crime had been

well established in Havana long before Luciano's landmark voyage. During the 1930's

Meyer Lansky "discovered" the Caribbean for northeastern syndicate bosses and invested

their illegal profits in an assortment of lucrative gambling ventures. In 1933 Lansky

moved into the Miami Beach area and took over most of the illegal off-track betting and a

variety of hotels and casinos.(47) He was also reportedly responsible for organized

crime's decision to declare Miami a "free city" (i.e., not subject to the usual rules of

territorial monopoly). (48) Following his success in Miami Lansky moved to Havana for

three years, and by the beginning of World War 11 he owned the Hotel Nacional's casino

and was leasing the municipal racetrack from a reputable New York bank.

Burdened by the enormous scope and diversity of his holdings, Lansky had to delegate

much of the responsibility for daily management to local gangsters. (49) One of Lansky's

earliest associates in Florida was Santo Trafficante, Sr., a Sicilian-born Tampa gangster.

Trafficante had earned his reputation as an effective organizer in the Tampa gambling

rackets, and was already a figure of some stature when Lansky first arrived in Florida. By

the time Lansky returned to New York in 1940, Trafficante had assumed responsibility

for Lansky's interests in Havana and Miami.

By the early 1950's Traflicante had himself become such an important figure that he in

turn delegated his Havana concessions to Santo Trafficante, Jr., the most talented of his six sons. Santo, Jr.'s, official position in Havana was that of manager of the Sans Souci

Casino, but he was far more important than his title indicates. As his father's financial

representative, and ultimately Meyer Lansky's, Santo, Jr., controlled much of Havana's

tourist industry and became quite close to the pre-Castro dictator, Fulgencio Batista. (50)

Moreover, it was reportedly his responsibility to receive the bulk shipments of heroin

from Europe and forward them through Florida to New York and other major urban

centers, where their distribution was assisted by local Mafia bosses.(51)

The Marseilles Connection

The basic Turkey-Italy-America heroin route continued to dominate the international

heroin traffic for almost twenty years with only one important alteration-during the 1950's

the Sicilian Mafia began to divest itself of the heroin manufacturing business and started

relying on Marseilles's Corsican syndicates for their drug supplies. There were two

reasons for this change. As the diverted supplies of legally produced Schiaparelli heroin

began to dry up in 1950 and 1951, Luciano was faced with the alternative of expanding

his own clandestine laboratories or seeking another source of supply. While the Sicilian

mafiosi were capable international smugglers, they seemed to lack the ability to manage

the clandestine laboratories. Almost from the beginning, illicit heroin production in Italy

had been plagued by a series of arrests-due more to mafiosi incompetence than anything

else-of couriers moving supplies in and out of laboratories. The implications were

serious; if the seizures continued Luciano himself might eventually be arrested. (52)

Preferring to minimize the risks of direct involvement, Luciano apparently decided to

shift his major source of supply to Marseilles. There, Corsican syndicates had gained

political power and control of the waterfront as a result of their involvement in CIA

strikebreaking activities. Thus, Italy gradually declined in importance as a center for

illicit drug manufacturing, and Marseilles became the heroin capital of Europe. (53)

Although it is difficult to probe the inner workings of such a clandestine business under

the best of circumstances, there is reason to believe that Meyer Lansky's 1949-1950

European tour was instrumental in promoting Marseilles's heroin industry.

After crossing the Atlantic in a luxury liner, Lansky visited Luciano in Rome, where they

discussed the narcotics trade. He then traveled to Zurich and contacted prominent Swiss

bankers through John Pullman, an old friend from the rum running days. These

negotiations established the financial labyrinth that organized crime still uses today to

smuggle its enormous gambling and heroin profits out of the country into numbered

Swiss bank accounts without attracting the notice of the U.S. Internal Revenue Service.

Pullman was responsible for the European end of Lansky's financial operation:

depositing, transferring, and investing the money once it arrived in Switzerland. He used

regular Swiss banks for a number of years until the Lansky group purchased the

Exchange and Investment Bank of Geneva, Switzerland. On the other side of the Atlantic,

Lansky and other gangsters used two methods to transfer their money to Switzerland:

"friendly banks" (those willing to protect their customers' identity) were used to make

ordinary international bank transfers to Switzerland; and in cases when the money was

too "hot" for even a friendly bank, it was stockpiled until a Swiss bank officer came to

the United States on business and could "transfer" it simply by carrying it back to

Switzerland in his luggage. (54)

After leaving Switzerland, Lansky traveled through France, where he met with high ranking

Corsican syndicate leaders on the Riviera and in Paris. After lengthy discussions,

Lansky and the Corsican's are reported to have arrived at some sort of agreement

concerning the international heroin traffic. (55) Soon after Lansky returned to the United

States, heroin laboratories began appearing in Marseilles. On May 23, 1951, Marseilles police broke into a clandestine heroin laboratory-the first to be uncovered in France

since the end of the war. After discovering another on March 18, 1952, French authorities

reported that "it seems that the installation of clandestine laboratories in France dated

from 1951 and is a consequence of the cessation of diversions in Italy during the previous

years. (56) During the next five months French police uncovered two more clandestine

laboratories. In future years U.S. narcotics experts were to estimate that the majority of

America's heroin supply was being manufactured in Marseilles.

2.

Marseilles: America's Heroin Laboratory

FOR MOST Americans, Marseille means only heroin, but for the French this bustling

Mediterranean port represents the best and the worst of their national traditions. Marseille

has been the crossroads of France's empire, a stronghold of its labor movement, and the

capital of its underworld. Through its port have swarmed citizens on their way to colonial

outposts, notably in North Africa and Indochina, and "natives" permanently or

temporarily immigrating to the mother country. Marseilles has long had a tradition of

working class militancy-it was a group of citizens from Marseilles who marched to Paris

during the French Revolution singing the song that later became France's national

anthem, La Marseillaise. The city later became a stronghold of the French Communist

party, and was the hard core of the violent general strikes that racked France in the late

1940's. And since the turn of the century Marseilles has been depicted in French novels,

pulp magazines, and newspapers as a city crowded with gunmen and desperadoes of

every description-a veritable "Chicago" of France.

Traditionally, these gunmen and desperadoes are not properly French by language or

culture-they are Corsican. Unlike the gangsters in most other French cities, who are

highly individualistic and operate in small, ad hoc bands, Marseilles's criminals belong to

tightly structured clans, all of which recognize a common hierarchy of power and

prestige. This cohesiveness on the part of the Corsican syndicates has made them an ideal

counterweight to the city's powerful Communist labor unions.

Almost inevitably, all the foreign powers and corrupt politicians who have ruled Marseilles for the last forty years have allied themselves with the Corsican syndicates:

French Fascists used them to battle Communist demonstrators in the 1930's; the Nazi

Gestapo used them to spy on the Communist underground during World War II; and the

CIA paid them to break Communist strikes in 1947 and 1950. The last of these alliances

proved the most significant, since it put the Corsican's in a powerful enough position to

establish Marseilles as the postwar heroin capital of the Western world and to cement a

long-term partnership with Mafia drug distributors.

The Corsicans had always cooperated well with the Sicilians, for there are striking

similarities of culture and tradition between the two groups. Separated by only three

hundred miles of blue Mediterranean water, both Sicily and Corsica are arid,

mountainous islands lying off the west coast of the Italian peninsula. Although Corsica

has been a French province since the late 1700s, its people have been strongly influenced

by Italian Catholic culture. Corsicans and Sicilians share a fierce pride in family and

village that has given both islands a long history of armed resistance to foreign invaders

and a heritage of bloody family vendettas. And their common poverty has resulted in the

emigration of their most ambitious sons. Just as Sicily has sent her young men to

America and the industrial metropolises of northern Italy, so Corsica sent hers to French

Indochina and the port city of Marseilles. After generations of migration, Corsican's

account for over 10 percent of Marseilles's population.

Despite all of the strong similarities between Corsican and Sicilian society, Marseilles's Corsican gangsters do not belong to any monolithic "Corsican Mafia." In their pursuit of

crime and profit, the Mafia and the Corsican syndicates have adopted different styles, different techniques. The Mafia, both in Sicily and the United States, is organized and

operated like a plundering army. While "the Grand Council" or "the Commission" maps

strategy on the national level, each regional "family" has a strict hierarchy with a "boss",

"under boss," "lieutenants," and "soldiers." Rivals are eliminated through brute force,

"territory" is assigned to each boss, and legions of mafiosi use every conceivable racket prostitution,

gambling, narcotics, protection-to milk the population dry. Over the last

century the Mafia had devoted most of its energies to occupying and exploiting western

Sicily and urban America.

In contrast, Corsican racketeers have formed smaller, more sophisticated criminal syndicates. The Corsican underworld lacks the Ma a's formal organization, although it does have a strong sense of corporate identity and almost invariably imposes a death sentence on those who divulge information to outsiders. A man who is accepted as an ordinary gangster by the Corsicans "is in the milieu," while a respected syndicate boss is known as un vrai Monsieur. The biggest of them all are known as paceri, or "peacemakers," since they can impose discipline on the members of all syndicates and mediate vendettas. While mafiosi usually lack refined criminal skills, the Corsican's are specialists in heroin manufacturing, sophisticated international smuggling, art thefts, and counterfeiting. Rather than restricting themselves to Marseilles or Corsica, Corsican gangsters have migrated to Indochina, North Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, Canada, and the South Pacific. In spite of the enormous distances that separate them, Corsican racketeers keep in touch, cooperating smoothly and efficiently in complex intercontinental smuggling operations, which have stymied the efforts of law enforcement authorities for a quarter century.(1)

Cooperation between Corsican smugglers and Mafia drug distributors inside the United States has been the major reason why the Mafia has been able to circumvent every effort U.S. officials have made at reducing the flow of heroin into the United States since the end of World War It. When Italy responded to U.S. pressure by reducing its legal pharmaceutical heroin production in 1950-1951, the Corsican's opened clandestine laboratories in Marseilles. When U.S. customs tightened up baggage checks along the eastern seaboard, the Corsican's originated new routes through Latin America. When Turkey began to phase out opium production in 1968, Corsican syndicates in Indochina developed new supplies of morphine and heroin.

Marseilles is the hub of the Corsican's international network. During the First Indochina War (1946-1954), Corsican syndicates made a fortune in illegal currency manipulations by smuggling gold bullion and paper currency between Saigon and Marseilles. In the 1950's Corsican gangsters supplied a booming black market in "tax-free" cigarettes by smuggling American brands into Marseilles from North Africa. Corsican heroin laboratories are located in Marseilles's downtown tenements or in luxurious villas scattered through the surrounding countryside. Most of the laboratories' morphine base supplies are smuggled into the port of Marseilles from Turkey or Indochina. Marseilles is the key to the Corsican underworld's success, and the growth of its international smuggling operations has been linked to its political fortunes in Marseilles. For, from the time of their emergence in the 1920's right down to the present day, Marseilles's Corsican syndicates have been molded by the dynamics of French politics.

The first link between the Corsican's and the political world came about with the

emergence in the 1920s of Marseilles's first "modern" gangsters, Francois Spirito and

Paul Bonnaventure Carbone (the jolly heroes of 1970's popular French film,

Borsalino). Until their rise to prominence, the milieu was populated by a number of

colorful pimps and gunmen whose ideal was a steady income that ensured them a life of

leisure. The most stable form of investment was usually two or three prostitutes, and none

of the gangsters of this pre-modern age ever demonstrated any higher aspirations Carbone

and Spirito changed all that. They were the closest of friends, and their twenty year

partnership permanently transformed the character of the Marseilles milieu. (2)

The first link between the Corsican's and the political world came about with the

emergence in the 1920s of Marseilles's first "modern" gangsters, Francois Spirito and

Paul Bonnaventure Carbone (the jolly heroes of 1970's popular French film,

Borsalino). Until their rise to prominence, the milieu was populated by a number of

colorful pimps and gunmen whose ideal was a steady income that ensured them a life of

leisure. The most stable form of investment was usually two or three prostitutes, and none

of the gangsters of this pre-modern age ever demonstrated any higher aspirations Carbone

and Spirito changed all that. They were the closest of friends, and their twenty year

partnership permanently transformed the character of the Marseilles milieu. (2)

This enterprising team's first major venture was the establishment of a French-staffed brothel in Cairo in the late 1920's. They repeated and expanded their success upon their return to Marseilles, where they proceeded to organize prostitution on a scale previously unknown. But more significantly, they recognized the importance of political power in protecting large-scale criminal ventures and its potential for providing a source of income through municipal graft.

In 1931 Carbone and Spirito reached an "understanding" with Simon Sabiani, Marseilles's Fascist deputy mayor, who proceeded to appoint Carbone's brother director of the

municipal stadium and open municipal employment to associates of the two underworld

leaders. (3) In return for these favors, Carbone and Spirito organized an elite corps of

gangsters that spearheaded violent Fascist street demonstrations during the depression