DuPont Dynasty

Behind the Nylon Curtain

Gerard Colby

Six

THE NEW ORDER

6.1

APPEARETH THE “SAVIOR”

On January 21, 1902, Eugene DuPont, 62-year old president of DuPont Company,

failed to appear at his office. He had a cold, it was reported. One week later he was

dead.

Eugene’s death from pneumonia was more than just a personal shock to his family. It

was also a business crisis, perhaps the greatest the family had ever faced. Decades of

failing to bring young DuPont's into the seats of power now came back to haunt the

elders in their time of greatest need. Eugene’s younger brother Frank, the next in line of

succession, was too ill to take over the firm. In fact, he would join his dead brother at

Sand Hole within two years. Eugene’s other brother, Dr. Alexis, was also ill. He too

would die within weeks of Frank. Their cousin and fellow partner, Charles I. DuPont,

although still in his thirties, was also failing. He would be dead before the year was out.

In all, DuPont’s board of directors was a round table of dying knights unable to rule or

save the family’s industrial kingdom.

Desperate, the elders turned to Colonel Henry A. DuPont, the only remaining

director, but Henry had deeply involved himself in Delaware politics. For years he had

been following to the point of obsession the quest for the political holy grail of his life:

Delaware’s seat in the U.S. Senate. Because of a bitter personal feud with one John

“Gas” Addicks over political control of the state, his obsession had reached the point of

blind fanaticism. With an election approaching, he refused to tie himself down with the

enormous responsibilities of captaining the corporate armada called DuPont.

It was cruel irony for the DuPont's. Henry DuPont, who had devotedly given the

company fifty toilsome years of his life, had actually started this crisis with his policy

of keeping the family youth out of positions of power and favoring his own sons for

succession. Now with one son, William, scandalously exiled, his last remaining and

favorite son, Henry, refused to lead the company at its time of greatest need.

Some in the family looked to Alfred. “Too young,” cautioned Frank,

1 and too

impulsive. With just such a remark, Frank summarily doused what family fires may have

been kept burning for that eldest son of E. I. DuPont II. Alfred was hurt, of course, but

surprisingly kept his opinions to himself. He suspected what was about to happen and

for once in his life kept a cool head in front of his family, then secretly took a train to

New York to visit its leading banks.

While Alfred scrambled about Wall Street, the elders announced the predictable decision. No one in the family, they felt, had the qualifications to run the company. They

were trapped into the most unfortunate of alternatives: sellout. Why lose a family

fortune by turning the company over to inexperienced youth, they reasoned, and their

reasoning was indeed sound. We must sell the company to Laflin and Rand, they

explained, the only firm with enough capital to buy us out at our own price. Actually, it

wasn’t as bad as it sounded at first. Although supposedly a competitor, the DuPont

family actually held a substantial interest in Laflin and Rand. In fact, Laflin’s president,

J. Amory Haskell, had been an employee and lieutenant of Lammot DuPont and had

helped Ethel DuPont’s husband, Hamilton Barksdale, take over Repauno Chemicals

after William du Pont’s exile. Haskell had been transferred to Laflin and Rand after DuPont became the largest, although still minority, stockholder. With Haskell running the

show, nothing would actually change but the name of the firm, and perhaps, with

persuasion, that might also remain.

But it was still a terrific blow to the family’s pride. Sadly they met at a stockholder’s

meeting to write the formal obituary to E. I. DuPont’s powder company. They would ask

$12 million from Laflin and Rand, Frank explained. After some discussion, Colonel

Henry rose to formally move for the record that the company’s assets be offered for sale

to Laflin and Rand, and that Hamilton Barksdale serve as negotiator. Alfred had been

quiet during the meeting, clad in grimy work clothes from the yards. When Henry made

his motion, Alfred closed his eyes, perhaps to help his failing hearing. Then he rose to

offer an amendment: that they be sold “to the highest bidder.” Only a harmless formality,

the elders felt, and Henry accepted the amendment as “friendly” and the motion was

passed. Then the meeting was adjourned, the DuPont's breathing a sigh of relief that

Alfred had not made a scene. They sighed too soon.

Alfred suddenly threw himself in front of the door, blocking it. “Gentlemen,” he

exclaimed, “I’ll buy the business!”

2 Frank’s long face became drawn and irritated. He

said that was impossible. “Besides, it’s cash, you know.”

3 Alfred became furious. The

confrontation with Frank, delayed for years, had finally come. “Why not?” he exploded.

“If you can’t run the company, sell it to someone who can!”

4 His voice rising and

becoming more shrill, Alfred admonished the elders for holding back the family youth

and declared the company to be his birthright. “I pointed out to him [Frank] the fact that

the business was mine by all rights of heritage; that it was my birthright. I told him that I

would pay as much for the business as anybody; that furthermore I proposed to have it. I

told him I would require one week to perfect the necessary arrangements looking

toward the purchase of the business, and asked for that length of time.”

5 Who was better

qualified? Alfred demanded. For the first time in years, Frank was silent.

Colonel Henry had felt guilty during the whole affair. Alfred’s stand gave his

conscience and political ambition a way to redeem themselves.

“All right, I’m with you,”

6 he said, slapping a long hand on Alfred’s broad shoulder.

“Gentlemen, I think I understand Alfred’s sentiment in desiring to purchase the business.

I wish to say that it has my hearty approval. I shall insist that he be given the first

opportunity to acquire the property.”

Alfred had won the first battle, but not the war. Frank DuPont considered it just

another of Alfred’s scenes, making the whole transaction more difficult for everyone. In

the tradition since Antoine Bidermann, a phone call was made to the talented DuPont

in-law Hamilton Barksdale. Barksdale was an able executive and, as far as the elders

were concerned, a good choice for president pro tern. Dr. Alexis offered him the job.

Barksdale, catching the scent of family feud, wisely declined. “In my opinion,” he

told Dr. Alexis, “it would be a great misfortune for the company to place anyone at the

head of the concern until you have exhausted all efforts to secure a man of your own

name to take the helm.”

7

It was obvious that all efforts had not been exhausted. Alfred

still had one week to make good his challenge.

Alfred used every minute of that week. He knew his executive abilities were lacking

and, as his efforts at Wall Street had failed, he needed help in financing his project.

Only one man he had ever known could provide the talents he needed. He hopped into

his automobile and drove through the streets of Wilmington until he came to 808 Broome

Street, the home of his cousin and former schoolmate, T. Colemen du Pont.

6.2

APPEARETH THE KENTUCKY KING

Thomas Coleman DuPont was from the Kentucky branch of the family where Uncle

Fred, Alfred’s guardian, had ruled. The son of Bidermann DuPont, Uncle Fred’s brother,

Coleman had been Alfred’s roommate at M.I.T. But he was more than just a roommate to

his younger cousin. He was Alfred’s teacher and hero. A huge, dark, handsome man,

Coleman was 6 feet, 4 inches of charm and solid muscle. At Urbana College in Ohio he

had captained the football and baseball teams, stroked the crew, and ran the hundred yard

dash in ten seconds flat. Coleman could drink, fight, and play the role of he-man

better than anyone Alfred had ever met, with the possible exception of John L. Sullivan.

After finishing M.I.T., he rivaled Alfred for the hand of their cousin Alice DuPont,

called “Elsie” in the family. Typically, Coleman won and carried his bride off to

Central City, Kentucky, where his father owned coal mines, and his uncle just about

everything else.

Coleman had a reputation for having a big heart. When his father discovered a rich

deposit of coal, for example, Coleman celebrated Thanksgiving by sending each coal

miner just what he needed most—a free bag of coal. When he installed the first tub with

running water in that part of Kentucky, he proudly let in the poor people who had come

from miles around to see and marvel. Coleman could flash the biggest smiles at times like that.

Like Alfred, Coleman worked his way up in business. Starting as a mining

apprentice, he was soon superintendent and chief engineer. He even joined the Knights

of Labor to try to get a feeling for the workers and their thinking. Apparently, Coleman’s

class background prevented him from understanding much. He couldn’t comprehend

why the miners were angry about his father’s paying them only $1.25 to $1.75 a day for

their hazardous labor. He also could not understand why the Knights of Labor finally

struck his father’s mines in 1884.

His past membership notwithstanding, Coleman crushed the Knights’ strike by using

convicts as strikebreakers. Pulling strings in political circles, he forced the prisoners to

march under armed guard from the stockade at Shegog Crossing to his mines, crossing

the angry picket lines. There, under the barrels of shotguns, the prisoners mined for the

DuPont's as slave labor till dusk and then were marched back to prison. Finally one

prisoner was shot to death trying to escape; Coleman remained his usual cool and

indifferent self, but that death was too much for the miners. Faced with starvation in

their homes and the likelihood of more prisoners dying, they gave in. With a bellowing

laugh, Coleman lit up one of his huge cigars in celebration and flashed that famous grin.

In retaliation for lost profits, Coleman then decided to teach the workers who was

boss. Miners in those days were paid by the tonnage of coal remaining on top of

screens. Coleman changed the size of the screens’ holes from 1½ inches to 2 inches.

Thus less coal stayed on top of the screen, returning fewer dollars to the miners for their

labor, forcing the workers to labor twice as fast and hard to make the same wage per

day. Coleman’s scheme was an obvious attack on the workers, an effective wage cut and

speed-up. Again the miners tried to fight back with another strike in 1887, and again

Coleman used scabs to crush the strike. The 2-inch screens remained. Coleman

celebrated by buying control of Central City’s major newspaper, The Argus, and

renaming it the Central City Republican.

Six years later, in 1893, Coleman ran for public office, aspiring to be Central City’s

second mayor. The campaign issue at the time was labor, its rights and its needs.

Predictably, he was defeated, and just as predictably, Coleman couldn’t understand why.

“I won’t stay in a place where that’s all they think of me,”

8 he complained, his ego hurt.

In 1895 T. Coleman DuPont left Central City, never to return and never to be missed.

Coleman went to Johnstown, Pennsylvania, to join his friends J. Moxham and Tom

Johnson and take the post of general manager of their Johnson Company, later to become

Lorain Steel and a part of J. P. Morgan’s U.S. Steel. Soon “Coly” was the driving force

and president of a score of companies, always promoting new deals with his huge size,

gusto, and growing management reputation. When he bought Johnstown’s street railway,

he profited so well that he branched out into speculating with its properties, buying low here, selling high there.

In 1900 Coleman moved to Wilmington following his latest acquisition—a local

button factory. For one reason or another, the factory failed to produce a single button,

and Coleman, eager to avoid any tarnish on his image as a financial soldier of fortune,

dropped the company like it had the plague. Instead, he involved himself again in land

speculation and bought a mansion at 808 Broome Street, which he later turned into a

country club for his children and many friends, reigning like a king over weekly dances.

It was here that Alfred went to see Coleman about his plan to buy the family business.

“Al, it’s a big thing,” Coleman said. “I’ll have to talk to Elsie.”

9 Alfred left while

Coleman the Giant ran to his tiny wife for advice. Elsie DuPont, it seemed, was

Coleman’s real source of strength. He completely relied on her, for behind the powerful

bulk of Kentucky steel was a secret weakness—Coleman was frankly a scared little

boy. He was frightened to death of failure. Often he would suffer severe fits of nervous

indigestion during business trips, and Elsie constantly kept a bag packed in case

Coleman telegram for help. In such times only Elsie could shore him up and pull the

deal through.

After Coleman explained Alfred’s proposal, Elsie’s face wrinkled into a frown. “You

know what it is to be in business with your relatives,”

10 she warned. DuPont's do not

make good business partners: each thinks his way is divinely superior. In this regard,

however, Coleman was no exception in the family. “I won’t go in,” he finally resolved,

“unless I get a free hand.”

11 “A free hand” meant the presidency. Alfred could be the

vice-president and general manager, a role close to the mills and one which perfectly

suited Alfred. But Coleman also had one more condition. He wanted his cousin, Pierre DuPont, to join them as treasurer. Alfred agreed. He knew Pierre’s qualifications. Since

leaving the Brandywine, Pierre had become president of the Johnson Company and had

worked closely with Coleman on many other deals. He had an excellent mind for

finances and his calculated caution would be a good balance to Coleman’s boldness.

Too good, as time would prove. Alfred would later regret this decision.

United in common purpose for the present, the cousins then met with the elders. With

the prestige of victory that always bowled over his opposition, Coleman displayed his

best as a slick promoter. Tall and powerfully built, his eyes flashing with emotion as his

body made sweeping gestures, he was an impressive sight and soon dominated the

gathering like any good showman. In a deep booming voice, he proposed to pay more

than the minimum $12 million the elders wanted. The exact amount, he assured them,

would depend on a survey of the company’s assets. With his elders obviously pleased,

Coleman then slipped in his plan. He suggested the sellers accept notes worth $12

million with 4 percent interest plus 28 percent of the common stock in the new

corporation in exchange for their stock. “You wouldn’t want to cripple our plans by tying up all our cash,”

12 he said in a deep, calm voice. The elders looked at each other

for a moment and nodded agreement. Within a few hours it was all over. For a mere

$3,000 in cash, the legal cost of setting up the new company, the three cousins had

acquired the largest gunpowder trust in the history of the world.

6.3

COLEMAN’S FIREWORKS DISPLAY

While Coleman was signing contracts that would bring new life and a new age to DuPont, a new age of wonders had also been born to the world—the twentieth century.

Electricity brought light and teletypes, X rays and radio. The Flatiron Building rose

twenty stories into the Manhattan sky, dwarfing the gilded automobiles of the rich and

the taxi-cabs that sputtered about at its base.

But it was also an age of continued poverty for most Americans. By 1899, 250,000

Americans owned most of America’s wealth, while 50 million earned only $1.50 a day.

Prices fell, but so did wages.

The average family needed $800 a year to survive, yet most unskilled jobs paid no

higher than $500.

13 Starvation forced over a million women into the factories at even

less pay than their male counterparts earned,

14 80 percent of them receiving less than

$16 a week.

15 Even with both parents working there wasn’t enough to meet the basic

needs of most American families. The solution was agonizing. Working-class families

were forced to see their children leaving school to work for ten hours a day in a

sweatshop or a factory. In 1900 the census recorded 1,750,178 “gainfully occupied

children aged ten to fifteen.”

16 By 1910 almost two million children,

17 or 18 percent of

the nation’s total labor force, toiled for the “fat cats” of Wall Street. Working conditions

were horrible,

18 and the federal government knew about them.

19

In fact, the Supreme

Court had openly refused to intervene in child labor. The right of property was blatantly

held more important than the right of life. Some children were killed, many were

maimed for life, and many more were cheated. “At the Marble Coal Company,” for

instance, “twelve-year-old Andrew Chippie’s forty cents a day was regularly credited

against the debt left by his father, killed four years before in a mine accident.”

20 The

debt was to the inevitable company store. Meanwhile, coal mine owners like the DuPont's of Kentucky were enjoying their most profitable year yet as the United States

became the leading industrial nation in the world. Glass output, for example, rose by 52

percent since the depression of the 1890’s. No one but the parents noticed the ten-year old

children who tied stoppers on 300 bottles a day.

And no one could understand why anyone would want to shoot such a kindly old

imperialist like President William McKinley. Portly McKinley had just completed a

visit to the 1901 Pan-American exposition at Buffalo, where the promoters presented a breath-taking display of fireworks called “Our Empire,” filling the sky with exploding

stars and rockets representing Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines. “I killed

President McKinley because I done my duty,” exclaimed his radical assassin. “I didn’t

believe one should have so much service and another man should have none.… I don’t

believe we should have any rulers.”

21 Now what was that madman raving about? cried

the rulers. The “public opinion” of the rulers’ yellow press just couldn’t understand.

Neither did the DuPont's.

In fact, Coleman DuPont was too busy building his own empire to even care. Right

after he assumed the presidency, he disappeared from sight. Two weeks later he

reappeared at a director’s meeting in Wilmington and dumped a bag on the table.

“There’s control of Laflin and Rand,”

22 he boasted. The DuPont's were startled.

Coleman explained how he had approached John L. Riker, a major stockholder in Laflin

and Rand, and unfolded his plan to consolidate all powder companies in the United

States. Riker became infected with Coleman’s enthusiasm and the possible returns, and

finally agreed to exchange Laflin shares for those of the new DuPont corporation.

Coleman financed the deal through bonds of new front names, Delaware Investment

Co. and Delaware Securities Co.

23 As part of the deal, he also bought the Moosic

Powder Co.

DuPont now held control of the very company to which the elders would have sold

out.

But more than Laflin and Rand was at stake. Coleman’s decision to absorb DuPont’s

largest competitor implicitly meant that he intended to destroy the Gunpowder Trade

Association and absorb also the entire Powder Trust into DuPont Company. It was a

chilling move for what independent powder firms remained; chilling for them, but for

the DuPont's, breathtaking.

Coleman now controlled fifty companies strung out across the country, each with its

own manufacturing, administrative, and marketing operations. Coly quickly tore into

them, dissolving each operation and binding them together into one DuPont

International Corporation; J. Amory Haskell of Laflin and Rand was made vice president.

Any minority stockholders were bought out by a new dummy company, the E.

I. DuPont de Nemours Powder Co. Among those new companies absorbed were the

California Vizorit Powder Co. (high explosives), the American E. C. & Schultz

Gunpowder Co., and the International Smokeless Powder & Chemical Co.

Then Coleman, paying $240,000 to shake off price and trade agreements, simply

walked out of the Gunpowder Association, leaving behind a hollow shell. And just as

simply, the Powder Trust fell apart—mostly into DuPont hands. Gone now were the

secret trade pacts and ownership's. The DuPont Empire was now open for all to see.

Big, roistering Coleman now basked in the limelight of DuPont attraction. Family praises fed his vanity; he felt he deserved them, and he did. He had done the impossible.

Spending about $8,500 in cash, he had acquired through the issue of stock $35,955,000

in new assets. When the firm’s books had been accounted by Pierre and his small, tight lipped

secretary from Ohio, John J. Raskob, the company’s assets were found to be

worth over $24 million. That made the new total $59,955,000. (Pierre later certified

this amount on December 31, 1905.)

Even the elders, who had received only $15 million in new stocks for the old

company, were more than pleased. That is, Colonel Henry was, for he was the only one

of the old school still alive.

6.4

ADVANCING WITH “CIVILIZATION”

By 1905 “Coleman’s Company,” as it was increasingly being called among the family

(to Alfred’s growing concern), was directly manufacturing 64.6 percent of all U.S. soda

blasting powder, 80 percent of all saltpeter blasting powder, 72.5 percent of all

dynamite, 75 percent of all black sporting powder, 70.5 percent of all smokeless

sporting powder, and 100 percent of all military smokeless powder.

24

This last product, military smokeless powder, was a gift from the United States

government. DuPont, despite the experiments by Pierre, Frank, and Frank’s son, Francis

I. (and despite present claims to the contrary), had never discovered a perfected

smokeless powder. The U.S. government did. Patents covering the manufacture of Navy

and Army smokeless powder were all filed on the discoveries of men hired by the

government. Patent No. 489,684 was issued to Professor Charles E. Munroe, under the

employ of the Navy Department, on January 10, 1893. Its exclusive rights to

manufacture, however, were awarded to DuPont with no available reason given. Patent

No. 550,472 was issued to Lieutenant John B. Bernadou and Captain George A.

Converse of the U.S. Navy on November 26, 1895. Their discovery had been developed

at the U.S. Torpedo Station Laboratory at Newport, Rhode Island. Patent No. 586,586

was issued to Lieutenant Bernadou on July 20, 1895, as were Patents No. 652,455 and

652,505 on June 26, 1900, and Patent No. 673,377 on May 7, 1901.

The first patent by Professor Munroe could not be used by the DuPont's, however, its

specifications differing from those ordered by their greatest customers, the U.S. Army

and Navy. The second patent, filed by Lieutenant Bernadou and Captain Converse, was

more suitable to DuPont needs because it used alcohol-ether and colloid instead of

Munroe’s Metro-benzine colloid. Unfortunately for DuPont, this patent was purchased

by International Smokeless Powder Company, which partly explains Coleman’s

swiftness between 1903 and 1904 in completely buying out International. For the other

patents, Coleman slipped Bernadou $75,000. The Navy and Army, which actually

controlled the patents, were also very helpful. Navy and Army officers were given large blocks of International Smokeless Powder stock. Lieutenant Meigs, inspector at

Bethlehem Steel for the U.S. Navy, for example, was given 1,000 shares worth $100

each, a total value of $100,000.

25 Brigadier General James Reilly

26 and General

Ryan,

27 U.S. Army, were also large stockholders.

Military officers weren’t the only friends the DuPont's had. Patrons for their deadly art were everywhere in Washington, particularly in the White House. President Theodore Roosevelt’s Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine was met with great approval on the Brandywine. That American warships would protect the DuPont monopoly over Caribbean and Central American powder markets solidified the international cartel arrangements made a decade earlier.

Roosevelt’s Big Stick came down mercilessly in that area, paving the way for future American business expansion. In 1903 alone, Roosevelt landed U.S. troops in Honduras, the Dominican Republic, and Panama (as well as Syria). His greatest concern, however, was in Panama. There he intended to build a canal linking the Atlantic and Pacific naval and merchant fleets. That Panama was a territory of Colombia presented a problem at first. Attempts to pressure the Colombian senate to pass the Hay-Herrán Treaty giving the United States 100-year rights to the proposed canal met with defeat. Apparently the Colombian senate didn’t scare easily. Roosevelt’s response was typically Kiplan.

“Those jackrabbits—contemptible little creatures of Bogotá preventing the advance of civilization.” 28 Within months he was writing to agents in Panama. “How are things going on that revolution in Panama?” 29 Secretary of State Hay joined in by assuring Varilla, head of the Panama Canal Company, “The United States will not allow a revolution to fail.” 30 It didn’t.

Soon DuPont powder was blasting its way through Panama, and treasurer Pierre DuPont was chalking up higher and higher sales volumes. In the Caribbean, as in America, DuPont had a monopoly, and the digging of the Canal was not made any cheaper by noncompetitive prices for black powder and dynamite paid at taxpayers’ expense.

Between July 1905 and July 1906 the War Department presented the DuPont's with another token of their esteem: an order for 5,947,820 pounds of smokeless powder. The Delaware family showed its appreciation by charging 70 cents per pound for powder costing only 32 cents per pound to produce. Over $2.2 million was netted in profits.

Then another gift was laid on doorsteps along the Brandywine: an order for 300,000 pounds of powder for 32-caliber weapons. The powder had a net cost of 44 cents a pound, the Du Pont's charged 84½ cents per pound, profiteering another $230,000.

Such fraud, the Chicago Chronicle explained, “is greater than any profit ever derived by any seller of any product of staple sold in one year to the government in the history of the republic.” 31 But that wasn’t all. “The monopoly carrying on the business,” the Chronicle added, “was at the same time contracting with foreign nations to furnish ammunition with which they could attack American merchant men on the high seas.”

Where there is a demand, Coleman would say, there will be a supply. E. I. DuPont I would have been proud.

In 1906 Secretary of War William Howard Taft announced that the United States needed a reserve of 30 million pounds of powder to be adequately prepared for war. No one asked which war he was referring to, but one point was obvious: The Indian Head plant built by the government produced only one million pounds a year, all of it consumed in Navy target practice. Unless more government mills were built that could produce powder at cost (35 cents per pound) the War Department would have to pay DuPont’s price of 75 cents a pound. The Family would run off with a huge net profit of $12 million. One-tenth that amount would in one year build government factories that could produce the Secretary’s reserve at one-half the cost. Would the Secretary agree to build the plants? Taft gave his answer at the year’s end: He announced that the War Department had bought 6 million pounds of powder from the DuPont's that year.

Coleman’s head was swimming with power. In 1904, 50 cents was paid per common share of DuPont’s stock; in 1905, $3.50; in 1906, $6.50. One by one, Coly began to kill off the last independent competitors in America. First, American Powder: in 1909 it made $288,500; by 1907 it pulled in barely $30,000. The Lakeside Powder drew $60,000 in sales in 1905; by 1907, $23,500. 32 Then the Burton Powder Company fell under his financial blows; then the Cressona Powder Company; then Connell Powder. Coleman even turned on a member of his own family, Anne Ridgely DuPont, daughter of Eugene. Anne had married William Peyton, President of the Peyton Chemical Company of California. Over her protests, Coleman bought 3,000 of the company’s 6,500 shares and grabbed over $230,000 worth of Peyton’s bonds. Then he used the courts to win his claim of control. Soon Peyton was out of a job and a family rift began that was healed only by the salve of enormous profits under new management. Finally, only the Buckeye Powder Company of Peoria, Illinois, was left. That’s when Coleman’s troubles began.

Waddell was disgusted. As early as March 11, 1902, Coleman was disputing with his sales director, trying to force the stubborn old-timer under his thumb. 33 But Waddell was not a man to bend to anyone, even T. Coleman DuPont. On November 25, 1902, after twenty years of efficient service with DuPont, Waddell resigned. “A definite policy for the conduct of the business along fair and just lines might have evolved,” he wrote Coleman. “Instead of this, your letter indicates that it is the purpose to thrust the heads of departments, like roosters, into a pit to fight for supremacy. The stakes are too small. I have never been involved in such a disgusting condition of business.” 34 Waddell insisted that he would not become “an automaton in a business machine.”

Waddell established his own powder company, the Buckeye Powder Company in Peoria, Illinois. Coleman, of course, was not very happy about this turn of affairs. First he tried to buy into Waddell’s company. Waddell refused. Then Coleman hired lawyers, detectives, and spies to harass Waddell’s young firm. Waddell filed his first formal complaint with the U.S. Department of Commerce and Labor on October 19, 1903. “I have no desire to assume the role of a reformer,” he wrote Secretary George Cortelyou, “and have refrained from presenting this matter until it has become a necessity in defense of our business.” 35 But the harassment continued. Coleman sent agents to stir up the Peoria community against Waddell’s plant, spreading rumors that it was dangerous to the town. On March 3, 1905, Waddell filed another complaint against Coleman’s monopoly. “Mr. T. C. DuPont represents the American manufacturers,” he wrote Labor Commissioner James Garfield on DuPont’s trade agreements, “and furnishes the pooling data for associates.” 36 This complaint reached the Department’s Bureau of Corporations, but still no aid was given the beleaguered firm.

In 1906 Waddell’s firm, after two years of profitable business, finally began to falter as DuPont tightened its stranglehold, choking off capital reserves from Buckeye. Waddell then decided to fight back with bigger guns than complaints to government bureaucracies.

On June 16, 1906, Waddell published an open letter to the President and members of Congress exposing the DuPont's for their price fraud on brown and smokeless powder sold to the government. “Here is an absolute and exclusive monopoly,” he wrote, “superior to the government, entrenched at the Capitol, with its representatives in the House, Senate, and Departments.… It is not safe to entrust this DuPont monopoly with the most essential article for national defense, nor is it right to rob the people to build up this monopoly and fatten millionaries.” 37 No one could argue with that. Even Alfred had to admit he had put on a few pounds.

But Waddell’s language and facts grew stronger. “The market for the Government is cornered by a single group of conspirators,” 38 he said. If the government wants powder, Waddell pointed out, it must accept the bid of the DuPont Trust. “The welfare of the nation is in the balance against the DuPont Trust,” he concluded. “Our inquiry is personable and reasonable. Are you with the Powder Monopoly or the people?” 39

Apparently, Congress and the President couldn’t make up their minds. By the time 1907 rolled around, Waddell’s plant was slipping fast, his sales plunging from 1905’s $200,000 to $98,500. 40 One of the big factors in this decline was a mysterious explosion that destroyed Waddell’s plant.

Waddell was being ruined and he wanted revenge. Now no throne of power was too high to challenge—not even the President of the United States. Waddell turned the light on Theodore Roosevelt’s 1904 campaign closet and found a $70,000 DuPont skeleton. “If a $70,000 campaign contribution is sufficient,” he announced, “to obligate the executive and legislative department of the government to take $12 million from the taxpayers of the country and give it to the millionaires of this gigantic powder monopoly, the independent powder companies and voters of the country want to know it now.” 41

The earth on Capitol Hill began to tremble. On January 24, 1907, J. Amory Haskell,

vice-president of DuPont International, was called to testify before the House

Appropriations Committee to explain DuPont control over foreign patents that were

available to the government only at prices set by DuPont. Haskell was perfectly

composed as he suggested that DuPont had purchased foreign rights on a “secret

process” powder to protect the United States government. What Haskell did not suggest

but the Congressmen already realized was that DuPont control over those patents

actually restricted the government from their use except under DuPont dictates. “To my

mind,” Waddell later commented, “it represents imbecility, corruption, or collusion

between the Government and the Powder Monopoly.”

42

The earth on Capitol Hill began to tremble. On January 24, 1907, J. Amory Haskell,

vice-president of DuPont International, was called to testify before the House

Appropriations Committee to explain DuPont control over foreign patents that were

available to the government only at prices set by DuPont. Haskell was perfectly

composed as he suggested that DuPont had purchased foreign rights on a “secret

process” powder to protect the United States government. What Haskell did not suggest

but the Congressmen already realized was that DuPont control over those patents

actually restricted the government from their use except under DuPont dictates. “To my

mind,” Waddell later commented, “it represents imbecility, corruption, or collusion

between the Government and the Powder Monopoly.”

42

Waddell blasted the DuPont's again on February 2, calling for government-owned plants to break the government’s curious habit of providing charity for one of the country’s richest families. He charged that the DuPont's were frauding the government of over $2 million a year by charging 75 cents a pound for smokeless powder that only cost 31 cents to manufacture. It hit like a bombshell. The country’s headlines screamed his charges about DuPont donations to Roosevelt. Something had to be done.

On February 4, 1907, a mere two days after Waddell’s attack had rocked the sacred temple on the hill, Congress passed House Joint Resolution 224, directing the Secretary of Commerce and Labor to “investigate and report to Congress what existing patents have been granted to officers and employees of the Government of the United States upon inventions, discoveries, or processes of manufacture or production upon articles used by the Government of the United States, and how and what extent such patents enhance the cost or otherwise interfere with the use by the Government of articles or processes so patented.” 43

The government tried every method of placating Waddell. On February 20, Acting Commissioner of the Federal Trade Commission’s Bureau of Corporations, Herbert Knox Smith, even wrote a personal letter of appreciation to Waddell.

But Waddell was not to be placated, especially since his firm had finally collapsed. There were now no independent powder companies in America. Waddell’s hated enemy, Coleman DuPont, was in absolute control.

Ironically enough, it was the DuPont's who then came to Waddell’s aid by imprudently trying to seize control of the National Rifle Association at its annual convention at Sea Girt, New Jersey. The convention broke up under charges of corruption, which tarnished the DuPont public image. Nevertheless, when it reconvened at the 71st Regiment Armory in Chicago, the battle, with all its slanderous charges and counter charges, erupted again and finally elected was James A. Drain of Olympia. Drain was reportedly the candidate of the DuPont Trust. 44

By mid-1907 a national furor had arisen against the DuPont monopoly. But Coleman still wasn’t worried. After all, he knew the federal government was no trust-buster, despite the Sherman Anti-Trust Act. This was the greatest merger era of all times, when mergers horizontal (same market) and vertical (different markets of production) were taking place at a rate of 500 per year. Roosevelt, in his eight years of office, despite all his verbalism about a “Square Deal,” initiated only forty-four legal actions, only twenty of which were strong enough to win indictments. Of these twenty, the Roosevelt administration produced only one anti-trust conviction, against American Tobacco Company, which was allowed to continue as a monopoly anyway using interlocking directorates.

The Justice Department accepted “the rule of reason” in court, holding that not all monopolies were bad. In fact, it contended, some were good. Competition was recognized as an increasing problem of instability and more and more of the new business nobility were coming to agree with J. P. Morgan that industrial stability must replace laissez-faire capitalism. In popular literature, Horatio Alger with his hard work, puritan ideas, and inevitable success became the hero of the age; individualism was no longer self-sufficiency but domination over others. J. P. Morgan became the exceptional individual, given the right to rule by God, a sort of new “divine right” of industrial kings. In social philosophy, social Darwinism warped the theory of evolution into a justification for political domination at home and abroad, and the United States became understood as a unique, higher expression of man’s values, a position that gave support to its “manifest destiny” to control a large portion of the globe. 45 Thus, both monopolies at home and imperialism abroad received the theological and philosophical icing necessary for popular consumption.

“Progress is our most important product” advanced the notion of the business corporation working for the common good, in an effort to improve the poor reputation of the business elite. 46 The individual can manipulate the economy for the common good, monopolists explained. There was nothing wrong now with government and business cooperating to stabilize the economy for the common good, even if that usually meant only Wall Street’s common stock returns.

Roosevelt understood progressivism for what it really was—an instrument of conservatism. It was the rationalization of the old order to meet the needs of a new monopolistic order. Like all American presidents, Roosevelt was no foe of business interests. Even as governor of New York, he stifled an investigation of insurance companies that involved political and business associates. Roosevelt favored an informal détente between corporations and their government to iron out wrinkles in the system. When Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle raised a national outcry over the filthy and dangerous working conditions in the nation’s meatpacking plants, the Pure Food and Drug Act was written in a form acceptable to both Armour and Swift, while providing restrictions that eventually eliminated smaller, fly-by-night competitors. Federal meatpacking regulations, therefore, served the interests of monopoly rule in the long run; workers were soon working in clean white gowns and aprons that were no doubt a victory for them in improving their working conditions, but still went home to tubercular shanty towns.

Often, however, Roosevelt found that not all big businessmen shared Swift’s or Armour’s level of consciousness as a class with a sense of history, consciously adjusting philosophically and politically to the changing needs of industrial growth under private ownership. To develop order and stability in the domestic market, formal regulation sometimes had to take the place of informal detente. The formation of the Interstate Commerce Commission was a conscious attempt to regulate the nation’s railroad system to the benefit of the general corporate order and Roosevelt’s call in 1904 and 1905 for firmer control over rates produced the Hepburn Act of 1906. The functioning of the Federal Trade Commission was along these lines. Its purpose was (and is) to inform business on future contours of domestic economic policy. Some corporations took its advice seriously. Some didn’t. One of these was Du Pont.

The Du Ponts were Neanderthals when it came to understanding Roosevelt’s corporate “liberalism.” They were not against a well-organized society; it was just that their only understanding of benevolent despotism was primitive, or rather, medieval in character, like their social-feudal colony on the Brandywine. Although they fully accepted their “right” to monopolize their respective industry, and fully identified as a class with those who did likewise, they were nevertheless the happy, greedy victims of their own laissez-faire propaganda, embracing the very individualism they used to deter their workers from considering labor unions. It’s not surprising, therefore, that they didn’t respond to Roosevelt’s corporate therapy. In fact, they fought it all the way.

Roosevelt was in a dilemma. He was faced with DuPont obstinacy just when he needed flexibility most from them. Public sentiment had been stirred against the Powder Trust and workers were again in the streets because of a new economic depression. Charges of corruption against his War Department were being raised in the halls of Congress. Even he had been linked to these charges by the exposure of the $70,000 DuPont contribution to his 1904 campaign. The President was frankly embarrassed by the whole affair. He had to act.

He did. On July 30, 1907, Roosevelt’s Justice Department filed suit against the DuPont's and their companies for violation of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act.

Coleman DuPont was in a foam. Roosevelt’s Attorney General, Charles Bonaparte, had promised to allow DuPont lawyers to present their case before a government suit was initiated, but the Attorney General had pressed ahead on Roosevelt’s orders. “We then knew from actual experience,” wrote Coleman in a company memorandum, “that the Attorney General was not to be depended upon and placed no more confidence in his department.” 47 At least, that Attorney General. Under the next administration, Coleman would find the Attorney General’s office very dependable. He would also receive the valuable services of the Chairman of the Senate Committee on War Department Expenditures, Colonel Henry A. DuPont.

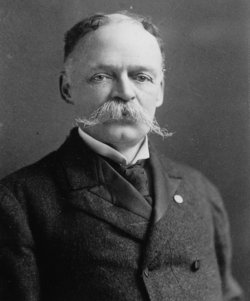

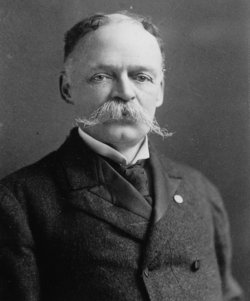

It has been said that of all the DuPont's, none made such an impact on the political

life of the state of Delaware as Henry Algernon DuPont. The son of “General” Henry DuPont, the president of Delaware’s largest railroad, the rewriter of the state constitution,

Henry was above all the Junker of Delaware.

It has been said that of all the DuPont's, none made such an impact on the political

life of the state of Delaware as Henry Algernon DuPont. The son of “General” Henry DuPont, the president of Delaware’s largest railroad, the rewriter of the state constitution,

Henry was above all the Junker of Delaware.

Henry was one of those vain men who loved military titles and insisted on being called “Colonel” even after he retired from the Army in 1875 and joined the family firm. With his silver-rimmed glasses and carefully waxed Van Dyke beard, he looked as stern and stiff as the high collars he wore. A military man in posture since his West Point training, he took his talents for command with him into the family firm.

Henry’s first job with his father’s company was to demand rebates from railroads which freighted DuPont products. These railroads were at the mercy of their largest customers along their lines, the monopolies, including DuPont. When such giants of industry as DuPont demanded rebates, the rails had little choice but to bend. Henry was particularly good at whipping his swagger stick, so good that he even became president of the Wilmington and Northern Railroad and from 1898 to 1913 served on the Board of Directors of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad.

With these railroad and DuPont offices, Henry inherited his father’s political power in Delaware. He made good use of it, apparently, for by 1889, the year of his father’s

death, he was already casting his eyes on Dover, the state capital, where the legislature

was then arguing over who was going to be the next U.S. Senator, popular election of

senators not having been introduced yet. It was at this time that Henry first crossed

swords with his lifelong foe, John Edward O’Sullivan Addicks.

With these railroad and DuPont offices, Henry inherited his father’s political power in Delaware. He made good use of it, apparently, for by 1889, the year of his father’s

death, he was already casting his eyes on Dover, the state capital, where the legislature

was then arguing over who was going to be the next U.S. Senator, popular election of

senators not having been introduced yet. It was at this time that Henry first crossed

swords with his lifelong foe, John Edward O’Sullivan Addicks.

John “Gas” Addicks was the son of a minor Philadelphia politician. Born in 1841, he quit school at the age of 14 to go to work. But Addicks developed an energy and cunning that soon made up for his wooden spoon. At the age of 19, he went to work for a Philadelphia flour mill merchant, Levi Knowles. Within two years, he was Knowles’s partner.

Addicks was as clever as he was ruthlessly ambitious. It was he who introduced Minnesota Spring wheat to eastern farmers. From profits he accrued and political favors for local political ward-heeling, he was rewarded with gas franchises in Boston, Brooklyn, Jersey City, and Chicago. John Addicks then went into the illuminating gas business, from whence came his nickname, “Gas.” By watering stocks and manipulating contracts, he grew rich and maintained an eight-acre estate near Claymont, Delaware. He sold this estate in 1888, three years after moving to Boston.

The next year “Gas” Addicks rediscovered Delaware. Back from Europe, where he made millions from Siberian railroad stock, he used $25,000 to buy Dover legislation that netted him a return of $2 million. 48 Now this was the kind of state he liked! Unfortunately, he didn’t know that it was already claimed turf—DuPont turf.

Addicks was a big man. At least he looked big, with his expensive clothes and huge pearl stuck in his ascot tie. With a broad forehead and jutting brow, he was as impressive a character as ever walked into the sleepy town of Dover. Soon Addicks was a big name in Delaware. What he didn’t know as he announced his candidacy for the U.S. Senate was that another name was even bigger—DuPont.

When the 1892 election rolled around, Addicks offered $10,000 per legislature vote. He wanted the DuPont man, Anthony Higgins, out. Spending over $100,000, he gained control of the Republican organizations in the downstate counties Kent and Sussex. Only New Castle remained as solidly opposed as Henry DuPont’s stone walls. Colonel Henry had been at work. He even wrote a letter to President Benjamin Harrison requesting that Watson Sperry, editor of the Wilmington Morning News, be given a federal appointment that would take the independent editor out of Delaware politics. 49 Sperry had been supporting another Republican by the name of Massey for senator. Such a factional dispute could hurt Higgins just when Addicks was mounting his attack. Harrison, a Republican, took the hint. Sperry became a special envoy on a secret mission to Persia. The long arm of DuPont can take one very far. Higgins, meanwhile, was reelected.

In 1895 a new senator had to be picked by the legislature. These were the days when U.S. senators were chosen by state legislatures. It would be almost twenty years before the Seventeenth Amendment would give this power to the people, and until then, Delaware’s legislators jealously guarded their prerogative. (In fact, the Seventeenth Amendment was rejected by the legislatures of only two states: Utah, the dominion of conservative Mormons and Guggenheim copper interests, and Delaware, the Duchy of DuPont.)

Addicks now controlled six votes, not enough to elect him but enough to check a clear Republican majority and prevent anyone’s election. Higgins was then made to step aside and Colonel Henry DuPont announced his candidacy, expecting Addicks’s house of money to collapse. To Henry’s surprise, Addicks’s camp suffered only one desertion. It was still a deadlock. Henry was furious and just as stubborn as Addicks—and richer. At this point, either Henry or Addicks—depending on whom one takes as source—but probably Addicks, made a statement that would resound in infamy through Delaware’s history to this day: “Me or nobody!” Delaware got nobody. The personal feud between two individuals would keep Delaware from being fully represented in the U.S. Senate for twelve long years. One, and only one, each insisted, would be the victor; as it turned out, in either case Delaware was the loser.

After thirty-five ballots, the Speaker of the Senate, William T. Watson, declared no election and adjourned the legislature. Henry was outraged, insisting he would have his election. He got the Speaker of the House to declare that Watson’s decision was invalid. The grounds were amazing. During the balloting, Governor Marvel had died and Watson, as Speaker of the Senate, succeeded him under the state constitution. But the constitution did not prohibit Watson from continuing on as Speaker of the Senate and he did, casting his ballots during the election. At no time was his vote ever challenged. But after his ruling, DuPont forces, including the Speaker of the House, declared Watson had no right to rule as Speaker of the Senate and declared both his ruling and right to vote invalid. That gave Henry the majority he needed. The Speaker of the House issued a certificate of election and Henry moved to Washington demanding the Senate seat him.

Delaware was shocked by DuPont’s dishonesty. The Wilmington Every Evening repeated Watson’s right to vote. 50 The country was shocked also. The Philadelphia Public Ledger reiterated the position of the Wilmington paper, 51 and even the New York Times charged that Watson’s voting rights and ruling were “according to the state constitution and laws of all precedents in the state.” 52 Apparently the U.S. Senate agreed. On May 15, 1896, the Senate voted to refuse to seat Henry and sent him packing.

Colonel Henry returned to Wilmington a bitter man. For ten more years he waged a relentless war for the Senate seat. In 1898 his image was boosted when he was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his heroism in the Civil War. The medal was a little late—thirty-four years, to be exact. But it was noted that this was a time when newspaper headlines were warning, “WAR IS NOW INEVITABLE,” and the government needed good relations with the DuPont's to prepare munitions at “reasonable” rates for war with Spain and expansion overseas. Nevertheless, Henry proudly wore his medal at all public appearances.

The following year Addicks controlled twenty-one of fifty votes in the Legislature; Henry DuPont held only eight. But the Colonel had inherited his father’s stubbornness; now it was definitely Henry who cried “Me or nobody!” In 1901 Addicks had twenty two votes but again Henry denied Delaware its right to Senate representation. In fact for the next two years Delaware had no representative at all in the U.S. Senate. By 1903 Delaware had become a national scandal; under Theodore Roosevelt’s pressure, compromise senators James Frank Allee and L. Heister Ball were selected for remaining Senate terms. By 1905, however, the feud was renewed for one of the seats and still a deadlock persisted. The stubborn Junker of Delaware refused to surrender, especially when he was about to bring up his biggest gun, the president of DuPont Company.

With Coleman DuPont, Addicks finally met his match. Coly’s first move was to

smash Addicks’s machine by luring his hacks away with bribes. Henry gave thousands

to Sussex County Republicans.

53 Coleman then had George Kennan, the old secretary

for deceased Lammot DuPont, write a now-famous article in Outlook magazine

charging Addicks with “Holding Up a State.”

With Coleman DuPont, Addicks finally met his match. Coly’s first move was to

smash Addicks’s machine by luring his hacks away with bribes. Henry gave thousands

to Sussex County Republicans.

53 Coleman then had George Kennan, the old secretary

for deceased Lammot DuPont, write a now-famous article in Outlook magazine

charging Addicks with “Holding Up a State.”

Coleman was as efficient in organizing the campaign as he was ruthless in his threats. Henry felt things were going so well, he sailed off on a European cruise to relax his nerves. In June, Addicks announced he was pulling out in the interest of the Republican Party, his twelve-year hold on the party smashed in one short year by T. Coleman DuPont. On June 12 the Republican caucus nominated Henry by a vote of twenty to ten. On June 13, 1906, he was elected U.S. Senator.

Eight hours before, Addicks boarded a Dover train bound for New York. He never returned. The copper market soon fell as the 1907 depression began, and Addicks’s fortune disappeared. As Henry sat in the halls of federal government, the government began to hound Addicks right out of business. A legal fight arose out of his gas deals and resulted in a federal court awarding $4 million against him.

Addicks was reduced to hiding from subpoenas, living in poverty. Still the hunt went on. Two years after his defeat in Delaware, process servers found him in a dreary Hoboken tenement, living under an assumed name, his gas and light turned off for nonpayment by a company he had once owned. For eleven more years the harassment went on, “Gas” Addicks finally dying in the slums of New York on August 7, 1919, a forgotten and broken man.

For Delaware, as for DuPont Company, Coleman’s “new order” had arrived.

Right from the beginning of the new order under the three cousins, differences arose between Coleman and Alfred. Coleman wanted to close the Brandywine mills. Alfred objected. Coleman wanted to move the company’s headquarters to New York. Alfred again objected. In both cases, Alfred won.

Alfred, in turn, was worried about Coleman’s increasing power in the firm. Frank, Charles I., and Dr. Alexis were all dead. Colonel Henry had left for Washington. To replace them, Coleman brought his western clerk, Lewis L. Dunham, and his father’s friend, Arthur J. Moxham, into the company. Furthermore, Moxham joined the board of directors, as did J. Amory Haskell, former president of Laflin and Rand, and L. R. Beardslee and James G. Reilly, both from companies which Coleman had bought out, as well as Henry F. Baldwin, Coleman’s brother-in-law, and Hamilton Barksdale, Mrs. Coleman DuPont’s brother-in-law. Baldwin, Haskell, Barksdale, and Moxham were all given bonuses to make them shareholders, and Moxham, Barksdale, and Haskell were appointed to the executive committee as vice-presidents.

Pierre also brought his brothers into this circle, Irénée taking the post of assistant treasurer, and Henry Belin, William Kemble, and Lammot donning overalls for the powder works. J. Amory Haskell also brought in his brother, Harry Haskell, and his trusted assistant, Charles Copeland, later to marry Pierre’s sister Louisa.

Alfred was relieved that Francis I. DuPont, Frank’s son and Delaware’s single tax pioneer, headed the Carney’s Point plant and joined him on the executive committee. But there were many new young DuPont's that Coleman was bringing into the company whose first loyalty seemed to be to the big man from Kentucky: A. Felix DuPont, second son of deceased Frank; Eugene, Jr. and Alexis I. DuPont III, sons of deceased Eugene; Eugene E. DuPont, son of Dr. Alexis; Victor DuPont, Jr., of the exiled Victor line; and Colonel Henry’s son, Henry Francis DuPont. And the newest addition to the Board, fat and lazy Victor DuPont, Sr., was no help whatsoever. Clear warning flags flew when Coleman set up his Delaware Securities Co. and Delaware Investment Co. Of each, Moxham was president, Coleman vice-president, and Pierre treasurer. Alfred had been left out.

Alfred was worried. He knew about Coleman’s infamous card tricks. He did not want to deal with a man who held a stacked deck, which is what the board of directors and junior executives were beginning to appear to be.

Other disputes arose. Alfred and Coleman debated over the eight-hour work day, the cause célèbre of the rising labor unions. Coleman felt it was better to take the steam out of labor organizers approaching DuPont plants by voluntarily instituting the eight-hour day. Alfred bitterly opposed Coleman’s plan. In 1904 an eight-hour bill was before Congress. On November 2 Alfred wrote the Secretary of Commerce and Labor of his opposition and hope that the workers’ bill would be killed in Committee and never reach the floor for a vote. Alfred’s argument was typically patronizing. He insisted that he, not the workers, knew what was best for them. All the stale arguments were aired again, including the “right” of the worker to work as long as he liked. (The bill did not rule out compulsory overtime, however.) But his chief argument was from his class side of economics: it would necessitate costly reorganization, force DuPont to raise prices and employ more men in the mills, increase the chance of accidents (true only if DuPont increased its line speed-up—which, of course, it did as Alfred knew it would), and finally—the real point—it would “abridge the right of the employer to offer labor such terms and wages as he saw fit.” 1

Coleman and his directors disagreed, believing the eight-hour law would cut unemployment while still allowing the employer to extract through speed-up ten hours worth of labor in eight hours. Eventually, DuPont voluntarily decreased its ten-hour work day to eight hours, but not before Alfred had been forced out of control over the company’s production.

Another contention was a new invention by Alfred, a steel glazing barrel. Naturally, Alfred was very enthusiastic about it. The barrel cut the cost of a 25-pound keg of black powder from 84 cents in 1907 to 78 cents in 1910. It also cut workers to pieces when it exploded, as it was much more dangerous than the old wooden barrels. After four accidents, Coleman abandoned the barrel despite Alfred’s voiced disappointment.

By 1909 Alfred’s worth to the company was quickly fading. In 1902, when he rose to prominence in the firm, Alfred’s black powder was king. But for the next eight years, dynamite sales increased 300 percent while black powder’s sales rose by only 25 percent. By 1909 dynamite sales topped those of black powder by ten million pounds. Black powder had reached its all-time high in 1907 and now was declining.

So was Alfred. With no dynamite experience, he was becoming less indispensable to the firm and was increasingly irritating to Coleman now reigning in his new four-story offices in Wilmington. And what family ties had bound Alfred to the company were now quickly being frayed over the issue of Alfred’s marriage and his relationship with another young DuPont cousin, Alicia Heyward Bradford, the daughter of Eleuthera DuPont and Judge E. G. Bradford.

By 1902 Alfred and Bessie were seldom speaking. For one thing, Louis’s suicide had soured their marriage. Further, Bessie’s rudeness to Alfred’s sister Marguerite, and her cold manner to Alfred, kept his relatives away from Swamp Hall, effecting an isolation that Alfred resented. Then Alfred’s hearing failed in 1904 and he had to give up his amateur band. Drifting from ties in Wilmington, he began spending more time writing to and visiting with the Ball family, particularly young Jessie Ball. An old Virginian family, the Balls were friends who lived near his private hunting retreat at Cherry Island. It was there in November of 1904 that Alfred suffered his second physical blow within a year.

He was hunting with Bill Scott, superintendent of DuPont’s Pennsylvania mills, and some other friends. The men were spread out on the trail of game, Alfred and a friend on one side of a hedge, Scott thirty yards away on the opposite side. Suddenly Scott thought he heard something and wheeled and fired at the hedge. Alfred’s friend ducked, and as he did, he saw Alfred’s hat fly off. Then Alfred dropped his gun and fell, blood pouring from his face.

He was rushed to the University of Pennsylvania, where surgeons performed an operation on his left eye. Bessie hurried from Europe with their daughter, Maddie, but the visit was not a happy one for Alfred. While Maddie weeped at her father’s bedside, Bessie just stared at him coldly. Understandably, Alfred grew depressed.

When he returned to Swamp Hall, the family threw a Christmas party to cheer him up. It only made matters worse. He suffered a relapse and had to return to the hospital. There, Alfred had his eye removed and replaced with a glass one.

By September 1905 Alfred had left Swamp Hall and made financial arrangements with Bessie. Although he was by then a millionaire, his settlement for his wife and children was not generous: only $24,000 a year. A $600,000 trust fund for his four children, Alfred Victor, Maddie, Bessie, and Victorine, was set up, Alfred choosing a Philadelphia lawyer for his trustee. Bessie chose Pierre DuPont. It was to be the beginning of a long friendship between the two, as well as the opening shot of the greatest civil war in the history of the clan.

As early as 1901, Alfred had begun seeing Alicia Bradford and they in turn were seen on picnics together. Rumors started to fly along the Brandy-wine. Alicia’s mother was Eleuthera DuPont, daughter of the original Alexis I. Alicia’s father was the stern judge of the U.S. Circuit Court, Edward Green Bradford. The Judge got wind of the meetings and became furious. He wanted them stopped—immediately! Alfred was still a married man, and if he wasn’t, that was worse: then he was a divorced man!

Alicia became very frightened. Her father was a domestic tyrant who ruled over her life. “As a child,” she said years later, “I was frightened all the time—terrified of everything. Suddenly it came to me that my father was the cause of this. He had wanted me to be a boy.” 2 Alicia could not see Alfred, at least not this way.

Alfred then introduced Alicia to George A. Maddox, a handsome but not too bright boy employed by DuPont Company. Over the Judge’s objections, he arranged clandestine meetings for her and Maddox. Suddenly they shocked the family with their announcement of plans to marry. Alfred made all the arrangements, even setting up the Christ Church for the wedding. After the ceremony, he gave them a DuPont home, Louviers, the estate of Admiral Samuel DuPont. When word came that Alicia was almost immediately pregnant, the whispers along the Brandywine flew faster than the river itself.

Alfred immediately rewarded Maddox with a promotion. He became regional superintendent of black powder plants in the Midwest, jumping over more experienced men in line for the job. This position kept Maddox away from Alicia most of the time. But Alicia was seldom alone. Alfred became a constant visitor.

In 1903, the year Bessie gave birth to Alfred’s fourth child, Victorine, Alicia Maddox also gave birth to a daughter. She was named Alicia, and reportedly had unmistakable DuPont characteristics, obviously from her mother’s side.

For the next three years, while Maddox was usually hundreds of miles away, Alicia continued playing hostess to Alfred. In April 1906 Alicia lost her second child, a boy. The death must have been a shattering blow to her. She publicly drew ever closer to Alfred. It must have also affected Alfred. Within a month, moved out of pity for Alicia’s unhappiness, he filed for divorce.

In December Alfred’s divorce from Bessie was granted on the grounds of mental cruelty. From that day, Coleman grew less tolerant of his troublesome cousin. Then Maddox suddenly handed Coleman his resignation. A Philadelphia newspaper later reported that he was bringing suit against Alfred, but that he suddenly withdrew the suit before filing a bill of particulars.

The mystery grows deeper. Alicia suddenly disappeared. Far from prying family eyes, she was secluded in a mansion in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. She had secretly filed for divorce from Maddox and was awaiting its approval. On October 8, 1907, her waiting was ended. One week later Alfred and Alicia were in New York together. There they were married. The indefatigably improper Maurice DuPont was the best man.

The news hit the Brandywine like a blockbuster. “Al, now you’ve done it,” Coleman warned his cousin when he returned. “The family will never stand for this. Don’t you think you’d better sell out to me and get away from here?” 3

“I’ll see the family in hell first!” replied Alfred.

That kind of talk was family treason. As if that wasn’t bad enough, Alfred also turned his back on the company. He announced that he would not stand by the firm or accept any responsibility for it in the coming U.S. federal suit. Instead, he filed a motion to have his individual case separated from the company’s and dismissed. He denied knowing anything of the Gunpowder Trust, of Coleman’s companies, Delaware Securities and Delaware Investment, of any wrongdoing—of which the government was proving there was plenty. After three days of testimony, Alfred’s case was dropped by the government.

Coleman and Pierre were speechless. Although Coleman had also taken leave, claiming illness, and never appeared in court, at least he didn’t separate his claim of innocence from that of the company. In retaliation, Alfred was soon dropped from the company’s finance committee, allegedly for his deafness. Coleman’s in-law, Hamilton Barksdale, took Alfred’s place, while Pierre was made acting president during Coleman’s absence.

“The Count,” as Alfred was called by the family, was not through yet. After marrying Alicia, he refused to visit his children at Swamp Hall, probably at Alicia’s encouragement. Alfred’s daughter Maddie finally left Swamp Hall to join her father at his new Brandywine estate, Rock Farms. But Maddie didn’t stay long. She soon eloped to France with a Princeton undergraduate, John Bancroft, Jr., son of a wealthy textile manufacturer in Wilmington. Despite a hurried announcement of her pregnancy, Maddie’s marriage didn’t work out. Her husband soon threatened to sue her for divorce on the grounds of her admitted adultery with a young German student, Max Heibler, during their honeymoon. Bancroft cited Maddie’s newly born infant as a co-defendant named Max Heibler, Jr. Alicia, anxious to avoid scandal, intervened with promises of treasure and threats to “rip the hinges from any Delaware closet, DuPont cabinets among them.” Bancroft’s adultery suit was suddenly amended to desertion, and subsequently withdrawn. But by the arrival of a second child, Bancroft could take no more. A divorce was applied for and granted. Maddie remained in Germany, eventually marrying Max Heibler.

Somehow, Maddie’s letters on her marriage woes reached Coleman’s hands. It is not known whether he immediately turned them over to Alfred, but when he did, Alfred was furious, believing the letters had run the family gauntlet.

Alfred’s relations with Coleman deteriorated even further after that. By 1911 the two cousins were bidding against each other for property along the Brandywine. Coleman, as usual, won.

Alfred realized his grip on the company was slipping fast, but he was helpless to stop it. His previous indispensability in the firm continued to decrease with the decline of black powder. In 1910, despite the fact that black powder sold 500,000 pounds less than in 1904, Alfred built a half million dollar plant at Welpen, Minnesota. It was a triumph of monumental vanity and stupidity. At this point only the ties of family could hold him in the firm, and those he had literally told to go to hell.

Awaiting his inevitable fate with the company, Alfred contented himself with buying a new yacht, which he named “Alicia.” Then he halted his donations to the Wilmington Symphony Orchestra because of a snub to Alicia by Wilmington society circles. As a result, the orchestra was forced to disband.

Ugly rumors began to float around about Alicia’s previous marriage, causing Alicia to cringe and Alfred to grow frantic in rage. He traced them all down to two people, Mrs. Mary Bush, a widow of a Wilmington manufacturer, and Alicia’s stout aunt of 57 years, Elizabeth Bradford DuPont. Then Alfred did the unthinkable. He publicly filed legal suit against both women for slander. It wasn’t long before Philadelphia papers picked up their hottest “society” story of the year. The Philadelphia North American called it “The Women’s War that convulses Delaware.” 4 Even the New York World reported that the rumors about Alicia DuPont “are of such a nature that they cannot be published.” 5 The New York Sun exposed the family’s futile efforts to hold off Alfred, and named more DuPont women who could be expected to become involved: Victorine DuPont Foster, sister of Senator Henry A. DuPont; Alice DuPont Oritz, Elizabeth Bradford DuPont’s daughter; Eugenie Roberts, niece of Elizabeth Amy DuPont, spinster daughter of the late Eugene; and Mrs. Henry A. Thompson. 6

There was a family outcry. Alfred had gone too far. Elizabeth was the widow of the late Dr. Alexis DuPont, and Mrs. Bush’s adopted son had also married Alicia’s younger sister, Joanna DuPont Bradford. Alfred had involved the whole clan and it could not stand by and allow him to publicly drag the name of DuPont through the gutter. Private rumors were one thing; public suits were quite another.

Alicia’s aunt ran to her son-in-law, attorney Thomas F. Bayard, Jr., of an old distinguished family that had placed four of its members in the U.S. Senate. Bayard, a Democrat, wanted to be number five, but he needed DuPont support. He took the case gladly.

Mrs. Bush ran to May DuPont’s husband, attorney Willard Saulsbury. Although Saulsbury was no friend of “that tribe” which Coleman, Colonel Henry, and Pierre represented, he agreed to take the case. Saulsbury, it seems, also had designs on a Senate seat.

The case dragged on for months, and still Alfred filed no bill of particulars. The newspapers were slaughtering the carefully cultured DuPont image, which didn’t help build popular sympathy for the clan’s defense against the government’s anti-trust suit. The family begged Alfred to come to reason, to think of the family as a whole. When that didn’t work, they tried threats, Finally, Bayard and Saulsbury wrote to Alfred’s lawyer, J. Harvey Whiteman, warning him that unless a bill was filed within thirty days, the defense would move for nonprosecution.

Whether Alfred had proof or not will never be known. Four days later he withdrew the suit in the interest of “family honor.”

But Alfred had his personal revenge. He moved into Nemours, his new $2 million palatial estate of five square miles. It included sunken gardens, greenhouses, and two grilled gateways of bronze, one from Wimbledon Manor in England, the other from the Russian Imperial Palace of Catherine the Great. But the center of attraction was the mansion itself. Built of limestone, an architectural blend of French chateau and Southern plantation, it stood three stories high, had seventy-seven rooms, and housed scores of servants. Art treasures were scattered throughout. The drawing room alone, for instance, had a seventeenth-century rug worth $100,000. In the basement, “the Count” kept an arsenal of weapons, including a machine gun and a small cannon. As if that were not enough to discourage unwelcome visitors, Alfred surrounded the entire estate with a nine-foot-high stone wall at the top of which were embedded pieces of sharp broken glass “to keep out intruders, mainly of the name of DuPont.” 7

The family took the hint and stayed away. But Alfred had just begun to take his personal revenge. As he moved into Nemours, he evicted Bessie and the children from Swamp Hall. Then he had their home completely demolished. Alfred, of course, met his family obligation. He increased Bessie’s annuity by $1,200 to cover the rent for a home in Wilmington, a very generous offer, he believed, from a man then grossing over $400,000 every year from his holdings in DuPont Company alone.

The clan was appalled. Never had such ruthlessness been seen within the family since the original Irénée had cheated his stepsister. The family feared it was plunging to new lows.

Not low enough, as far as Alfred was concerned. When the federal antitrust case ended with a conviction after four years and sixteen volumes of testimony, Alfred refused to agree to an appeal.

It was the final act of family heresy. Family feuds could always be healed, but company rifts required deliberate action. The appeal went on, but not Alfred. In a prearranged meeting of the executive committee in January 1913, Alfred was relieved of all operating duties as general manager and vice-president. Crushed, “the Count” sailed for France to lick his wounds.

They had good reason to hope. After distinguishing himself with his anti-labor decisions on the Ohio bench, Taft became head of Roosevelt’s War Department in 1904. It was he who showered DuPont with such profitable contracts. When this great admirer of John D. Rockefeller ran for the presidency in 1908, T. Coleman DuPont offered a donation of $20,000. Taft, however, decided not to repeat Roosevelt’s mistake and risk the possibility of bad publicity, but assured Coleman of his sincere friendship with the Delaware family.

Coleman was more than a friend. He was the national director of the Republican Party’s Speaker Bureau and a member of the executive committee of the Republican National Committee. When criticism arose over his affiliation because of the anti-trust case, Coleman prudently handed in his resignation to Taft on September 22, 1908. Six days later he wrote Taft of his full support in the coming election. Coleman’s support meant something. “The General,” as he was later called because of his appointment as general of the Delaware National Guard, controlled Delaware politics like a feudal lord since he became Colonel Henry’s campaign manager in 1906.

After his election, Taft showed his appreciation by offering the office of Secretary of State to a DuPont lawyer, John C. Spooner. The former senator from Wisconsin decided to decline, the DuPont's bowing to the demands of John Rockefeller and Andrew Mellon, who wanted to put in their own man, Senator Philander Knox. Instead, the office of Attorney General was given to George W. Wickersham, the very DuPont lawyer who had counseled the building of the Powder Trust.

President Taft and Colonel Henry DuPont were close political colleagues. When Taft was campaigning for president, it was Colonel Henry who hosted a dinner in Delaware in Taft’s honor attended by many DuPont luminaries. Henry, a supporter of high tariffs that would protect industries like DuPont, felt no hesitation about writing Taft at Hot Springs, Virginia, right after the election explaining his position on reciprocity. 8 Henry even enjoyed occasional music and dinner at the White House. 9 When the old Junker of Delaware was maneuvering for reelection in 1911, Taft feared another national scandal and suggested that it would be “very advantageous” to Henry if his aides were to pay a visit to that maker of presidents and public image, Senator Mark Hanna, so that Henry’s candidacy would be handled “in the proper light.” 10

The visits were made but the light was not very proper. Henry bought the election and everyone knew it. “It is common testimony that in all the shameful history of the State,” wrote the New York Evening Post, “money was never used more freely and more openly about the polls than this year.…"

The only person who had the most at stake in the election of a Republican Legislature in Delaware is Senator Henry A. DuPont who is a candidate for reelection,and the only Republican candidate whose name will go before the Legislature, so far as is known. The only known reason for spending large sums of money to elect a Republican Legislature is to insure the choice of a Republican for U.S. Senator.