The One World Tartarians

The Greatest Civilization

Ever to Be Erased From History

James W. Lee

Chapter 20

Insane Insane Asylums

of the 19th Century

The overall question is “Did the NWO take over Tartarian buildings and then use them to

kill off the people of Tartary around the world after committing them to converted insane

asylums. The evidence appears conclusively likely! Remember, that according to Mr.

Fomenko, his-story does not begin until the beginnings of the elimination of Tartary in 1200 AD.

In London, England, the Priory of Saint Mary of Bethlehem, which later became known more

notoriously as Bedlam, was founded in 1247. In Spain, other such institutions for the insane

were established after the Christian Reconquista; facilities included hospitals in Valencia (1407),

Zaragoza (1425), Seville (1436), Barcelona (1481) and Toledo (1483). In Britain at the beginning of

the 19th century, there were, perhaps, a few thousand “lunatics” housed in a variety of disparate

institutions; but, by the beginning of the 20th century, that figure had grown to about 100,000.

This growth coincided with the development of alienism, now known as psychiatry, as a medical

specialty.

By the end of the 19th century, national systems of regulated asylums for the mentally ill

had been established in most industrialized countries. At the turn of the century, Britain and

France combined had only a few hundred people in asylums, but by the end of the century this

number had risen to the hundreds of thousands. The United States housed 150,000 patients in

mental hospitals by 1904. Germany housed more than 400 public and private sector asylums.

These asylums were critical to the evolution of psychiatry as they provided places of practice

throughout the world.

Throughout the asylums worldwide we see familiar patterns of incredible Tartary architecture

with many asylums having farms and livestock and cemeteries and crematories. Another main

theme is most of these structures became “overcrowded” up through the beginnings of the 20th

century, so more asylums were needed, yet the population numbers at the time do not justify the

immense size of the buildings or number of people they claim were committed. In California,

at the very onset of the California Gold Rush of 1849, we see several insane asylums said to be

erected to house those deemed insane as early as 1851, even though California’s population in no

way justified the immense size and scope of these structures.

The other blatantly obvious note is that these immense

insane asylums nearly look identical all around the world in

what they call “Gothic” and “Roman” architecture.

The Hospital de los Inocentes (Hospital of the Innocents)

was the first asylum in Europe founded in Valencia, Spain

in 1410 stands out due to its originality and there are historic

and cultural reasons to recognize its primacy. Furthermore, the organization and functioning of this institution and the model, spread like wildfire through

the entire Iberian Peninsula during the 15th Century and shortly after through American Spanish

speaking countries. In 1512 the Council of the city of Valencia decided to unite all the hospitals

of the city in one «Hospital General»and to extend the coverage to all kind of patients and all

types of forsaken. The hospital was destroyed by a fire in 1545.

The Bethlem Royal Hospital

Britain, England 1676

Bethlem Royal Hospital,

also known as St Mary Bethlehem, Bethlehem Hospital

and Bedlam, is a psychiatric

hospital in London. Its famous

history has inspired several

horror books, films and TV

series, most notably Bedlam, a

1946 film with Boris Karloff.

The hospital is closely associated with King’s College

London and, in partnership

with the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, is a major centre for psychiatric research. Originally the hospital was near Bishopsgate just outside the walls of the City of

London where the NWO bankers reside. Already in 1632 it was recorded that Bethlem Royal

Hospital, London had “below stairs a parlor, a kitchen, two larders, a long entry throughout the

house, and 21 rooms wherein the poor distracted

people lie, and above the stairs eight rooms more

for servants and the poor to lie in”.

St Luke’s Hospital for Lunatics was founded

in London in 1751 for the treatment of incurable pauper lunatics by a group of philanthropic

apothecaries and others. It was the second public

institution in London created to look after mentally

ill people, after the Hospital of St. Mary of Bethlem

(Bedlam), founded in 1246.

Ipswich Hospital, Australia

for the

Insane 1878

Australia Originally built as a benevolent

asylum, the Ipswich site never fulfilled this

purpose. Chronic overcrowding at Woogaroo

Lunatic Asylum dictated that the new facility

at Ipswich could provide a solution to this

problem.

USA Insane Asylums of the 19th Century

Friends Asylum

McLean Hospital

Many of the more prestigious private hospitals tried to implement some parts of moral treatment

on the wards that held mentally ill patients. But the Friends Asylum, established by Philadelphia’s Quaker community in 1814, was the first institution specially built to implement the full

program of moral treatment.

Bloomingdale Insane Asylum

Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital

Massachusetts General Hospital built the McLean Hospital outside

of Boston in 1811; the New York Hospital built the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum in Morningside

Heights in upper Manhattan in 1816; and the Pennsylvania Hospital established the Institute of

the Pennsylvania Hospital across the river from the city in 1841. Thomas Kirkbride, the influential

medical superintendent of the Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital, developed what quickly

became known as the “Kirkbride Plan” for how hospitals devoted to moral treatment should be

built and organized. By the 1890s, however, these institutions were all under siege. Economic

considerations played a substantial role in this assault. Local governments could avoid the costs

of caring for the elderly residents in almshouses or public hospitals by redefining what was then

termed “senility” as a psychiatric problem and sending these men and women to state-supported

asylums. Not surprisingly, the numbers of patients in the asylums grew exponentially. By the

1870s virtually all states had one or more such asylums funded by state tax dollars.

The McLean Asylum was founded in 1811 in a section of

Charlestown, Massachusetts that is now a part of Somerville,

Massachusetts. Originally named Asylum for the Insane, it

was the first institution organized by a group of prominent

Bostonians who were concerned about homeless mentally

ill persons “abounding on the streets and byways in and

about Boston”. The effort was organized by Rev. John Bartlett,

chaplain of the Boston Almshouse. The hospital was built

around a Charles Bulfinch mansion, which became the hospital’s administrative building; most

of the other hospital buildings were completed by 1818.

Bloomingdale Insane Asylum 1821

The Bloomingdale Insane Asylum

(1821–1889) was a private hospital for the

care of the mentally ill that was founded

by New York Hospital. It occupied the

land in the Morningside Heights neighborhood of Manhattan where Columbia

University is now located. The road leading

to the asylum from the thriving city of

New York (at the time consisting only of

lower Manhattan) was called Bloomingdale Road in the nineteenth century, and

is now called Broadway.

Kirkbride Insane Asylums (1844)

The Kirkbride model was designed by Thomas Story Kirkbride, an asylum superintendent

and one of the founders of the Association of Medical Superintendents of American Asylums

for the Insane, the precursor to the American Psychiatric Association. Kirkbride’s book, On the

Construction, Organization and General Arrangements of Hospitals for the Insane, published

in 1854, became the standard resource on the design and management of asylums in the mid to

late 19th century. The Kirkbride plan consisted of a linear design with a central administration

building and long wings on either side that radiated off the center building.

Danvers State Hospital(Mass)

Hudson River State Hospital(N.Y.)

Taunton State hospital(Mass.)

Buffalo State hospital

This design allowed for “maximum separation of the wards, so that the undesirable mingling

of the patients might be prevented.” The wings also allowed for separation of male and female

patients, and for separation of patients based on the severity of their illnesses. Dr. Kirkbride was

also heavily involved in civic affairs within the city of Philadelphia itself, as well as that of the

commonwealth. He was a member of the College of Physicians, the Philadelphia County Medical

Society, the Franklin Institute, the Historical Society of Philadelphia, the American Philosophical

Society, and an honorary member of the British Medico-Psychological Association.

Greystone State Hospital(N.J)

Worcester State Hospital(Mass)

In 1844, Dr.

Kirkbride was one of the original thirteen members who founded the ‘Association of Medical

Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane’ (AMSAII), serving as its secretary from

1848 to 1855, its vice-president from 1855 to 1862, and finally, as its president from 1862 to 1870.

S. Carolina State Hospital

Northampton State hospital(Mass)

Pennsylvania Hospital for Mental and Nervous Diseases, was a psychiatric hospital located

at 48th and Haverford Streets in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

St. Vincent's(St.Louis)

St Elizabeth State Hospital(Wash DC)

It operated from its founding in 1841 until 1997. In the winter of 1841, nearly 100 mentally ill

patients of Pennsylvania Hospital were slowly transferred in carriages from the bustling city streets

at 8th and Spruce Streets to a new, rural facility especially prepared for their care. The hospital

awaiting them offered a treatment philosophy and level of comfort that would set a standard for

its day. Known as The Institute of Pennsylvania Hospital, it stood west of Philadelphia, amidst

101 acres of woods and meadows.

Trenton State Hospital(NJ)

Dayton State Hospital(Ohio)

Two large hospital structures and an elaborate pleasure ground were built on a campus that

stretched along the north side of Market Street, from 45th to 49th Streets. Thomas Story Kirkbride,

the hospital’s first superintendent and physician-in-chief, developed a more humane method of

treatment for the mentally ill there, that became widely influential. The hospital’s plan became

a prototype for a generation of institutions for the treatment of the mentally ill nationwide. The

surviving 1859 building was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1965.

Waverly Hills Sanatorium(Louisville)

Athens Mental Hospital(Ohio)

Oregon State Hospital

Unlike other

asylums where patients were often kept chained in crowded, unsanitary wards with little if any treatment, patients at the Pennsylvania Asylum resided in private rooms, received medical treatment,

worked outdoors and enjoyed recreational activities including lectures and a use of the hospital

library. The facility came to be called “Kirkbride’s Hospital. Overcrowding had become a problem

in the original Pennsylvania Asylum for the Insane by the 1850s, so Kirkbride lobbied the Pennsylvania Hospital managers for an additional building. But by the mid-20th century, the 1841

hospital building proved unusable for this purpose and was demolished in 1959.

New Hampshire State Hospital

Orillia Asylum(Ontario Can.)

California Insane Asylums So the story goes…

The Insanity Law of 1897 created the State Commission on Lunacy which was given authority

to see that all laws relating to care and treatment of patients were carried out and to make recommendations to the Legislature concerning the management of hospitals for the insane. The 1897

law provided that each hospital should be controlled by a board of managers of five members

appointed by the Governor for four-year terms. The Lunacy Law reforms passed allowed no

insane persons to be associated with criminals, no open court hearings, judge not required to

assess detainees Institutions named Hospitals instead of asylums.

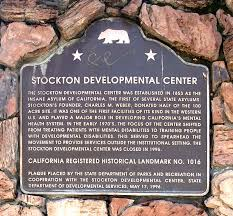

Stockton State Hospital

Stockton State Hospital or the Stockton

Developmental Center was California’s

first psychiatric hospital. The Hospital

opened in 1851 in Stockton, California

and closed 1995-1996. The site is currently

used as the Stockton campus of California

State University, Stanislaus. It was on

100 acres (0.40 km2) of land donated

by Captain Charles Maria Weber. The

legislature at the time felt that existing

hospitals were incapable of caring for the

large numbers of people who suffered

from mental and emotional conditions

as a result of the California Gold Rush,

and authorized the creation of the first

public mental health hospital in California. On May 17, 1853 the Stockton

General Hospital changed its name

to the Insane Asylum of the State of

California.

They even had created a female insane

building! The “Female Department,

Stockton State Hospital, Stockton.”

Stockton State Hospital was California’s first state psychiatric hospital, established in 1853. It was closed in 1996 and has since been

converted into a campus for California State University.

Sonoma Developmental Center

Sonoma Developmental Center 1891

It opened at its current location on November 24, 1891,

though it had existed at previous locations in Vallejo and

Santa Clara since 1884. The facility’s current name dates

from 1986 and was originally named The California

Home for the Care and Training of Feeble Minded

Children in 1883. The Home had primarily four types

of residents: the mentally handicapped, the epileptic, the

physically disabled, and the “psychopathic delinquent.”

From almost the start, the Home was overcrowded.

1889 Agnews State Hospital now Santa Clara

University Jesuit School Santa

Clara, CA

Agnews State Hospital

Today known as the world

famous Sun Microsystems

Developmental Center. In

1885 the Agnews Residential

Facility was established by the

California State Legislature as

a neuropsychiatric institution

for the care and treatment of the

mentally ill. Agnews, opened in

1889, was the third institution

in the state established for the

mentally ill. Twenty-one years

later, the greatest tragedy of the

1906 earthquake in Santa Clara

County took place at the old Agnews State Hospital. The multistory, unreinforced masonry building

crumbled, killing over 100 patients.

The Institution was then redesigned in, what was then, a revolutionary cottage plan spreading the low-rise buildings along tree-lined streets in a manner that

resembled a college campus. Now at the center of the Sun Microsystems/Agnews complex is the

Clock Tower Building (formerly the Treatment

Building) with its massive symmetrical clock

tower. In the 1906 earthquake, the main treatment building collapsed, crushing 112 residents

and staff under a pile of rubble. The victims were

buried in a mass grave on the asylum cemetery

grounds. The Institution was then redesigned

with low-rise buildings that resembled a college

campus.

Patton State Hospital

Patton State Hospital

The hospital was first

opened in August 1, 1893. In 1927 it was renamed Patton State Hospital after a member of the first

Board of Managers, Harry Patton of Santa Barbara. In 1889 the California legislature approved the

construction of Patton in order to provide care to those deemed mentally ill in southern California.

The Grand Lodge of the Free and Accepted Masons of California laid the cornerstone of the original

building on December 15, 1890.

At the time of its establishment, Patton was seen as a state-of-the-art mental

healthcare facility designed along the Kirkbride plan;

a popular plan for large asylums in the 19th century.

The Kirkbride, as the main building was called, was

an elaborate and grandiose structure with extensive

grounds which was meant to promote a healthy environment in which to recover. There are approximately

2,022 former patients buried in a field with a dirt road that runs up to it. These were patients whose bodies were left unclaimed or whose families

were unknown. Today it is well marked as cemetery ground and there is a mass grave marker

dedicated to the patients which can be seen approximately 50 yards from the street. The grounds

are located inside the

property fence in the

north-west corner. The

cemetery was full by

1930. 500 Patients with

Underground Railroad..What?

Napa State Insane Asylum Hospital

So the Story goes…

The Napa State Insane

Asylum Hospital was

housed primarily in

the four-story, stone,

castle-like, Gothic structure complete with seven towers. The towers were visible from rooftops in downtown Napa.

According to the hospital’s website, the facility was built to ease overcrowding at the Stockton

Asylum, the first state hospital. Construction started in 1872, and the first two patients, from

San Francisco, were admitted in 1875, taking only 3 years to build this incredible complex of

stone, iron and glass. The original design was for a 500-bed hospital! The population peaked

in 1960 with more than 5,000 residents but has declined steadily over the years due to changes

in treatment and admitting criteria. The towers were visible from rooftops in downtown Napa.

The website advises that initially 192 acres were purchased from a land grant owned by General

Mariano Vallejo. Eventually, through land acquisition, the acreage would total more than 2,000

acres. It stretched from the Napa River to the ridgeline east of today’s Skyline Park. n the

beginning, it was the Napa Insane Asylum, and early maps marked its location with the words

“Insane Asylum.” Later, the name was changed to Napa State Hospital, but, to local citizens, it

was called Imola. The striking stone castle was razed in the early 1960s and replaced by ho-hum,

unimpressive buildings of a design prevalent at that time.

So they are telling us the massive Gothic Structure aka Tartarian Moors building, with seven

towers was designed to house just 500 mentally insane people because there was an overflow in

Stockton’s Insane asylum 200 miles to the south of Napa! And that they had a fully functioning

farm with a railroad system underneath!!!

The cremated remains of as many as 5,000 Napa State patients are buried in a mass grave at Inspiration

Chapel on Napa-Vallejo Highway, McQueeney said. From the early to mid-1920s through the early

1960s, patients no longer were buried on hospital grounds, and no bodies were ever exhumed

from Napa State grounds, he said. Because burial acreage was limited, an on-site crematorium

was built at Napa State in the mid-1920s and was in use until sometime in the 1960s.

Burying and Burning the Evidence

Judy Zervas was on a wild goose chase, one

that led her to a seemingly empty field on the

sprawling grounds of Napa State Hospital.

Zervas, a Riverside resident who dabbles

in genealogy research, began searching this

summer for the grave site of Henry Shippey,

a distant cousin who died in 1919. Zervas saw

the initials “NSH” on the section of Shippey’s

death certificate that indicated his burial site,

but she wasn’t sure what the letters meant.“ I

asked a friend about it, who said, ‘What about

the state hospital?’” she said. Zervas contacted Napa State Hospital to ask where her relative was

buried, and said that her request initially was met with “a royal run-around.”

Her search ended when Napa State staff gave her access to a death ledger started in 2002 by

state hospital patient advocates. The ledger, part of what’s known as the California Memorial

Project, lists the names of some 45,000 people who lived and died on 10 hospital grounds around

the state. Used as a cemetery for indigent patients from about 1875 through the early 1920s, an

eastern portion of the campus holds 4,368 bodies, said Deborah Moore, Napa State’s public

information officer. Live oaks grace the site — trees that were probably there when the last Napa

State patient was buried there around 1924. Although it was once dotted with wooden grave

markers, today an outbuilding and a calf barn that hasn’t been used for decades sit atop the

seemingly empty field. So now we learn that the cemetery held 4,368 bodies, their were 5,000

cremated and 45,000 died on State Hospital grounds in California, yet the peak of the occupancy

rate of patients in 1960 was said to be only 5,000 from originally 500 people! As you will see below

many of these massive buildings had cemeteries and crematories onsight, as well as farms. These

were likely used to house the Tartarians before killing them after they had been separated from

their children well up until the 1930’s.

Mendocino State Asylum for the Insane, was

established in 1889. On December 12 1893, the

Hospital was finished and opened to patients,

receiving 60 from Napa State Hospital this same day.

Two days later, 60 more arrived from Stockton State

Hospital and on March 25th, 30 came from Agnews

State Hospital, bringing the population to 150. So,

too much overcrowding in Napa & Stockton asylums

so this was needed!?! The original main building,

completed in 1893, was razed in 1952.

Chapter 21

The Destruction of Great Tartary

The Great Purging 1840’s – 1930’s

Morey/Tesla Technology: Star Wars Now

And the Story Goes…

In the 1930’s Nikola Tesla announced

bizarre and terrible weapons: a death ray,

a weapon to destroy hundreds or even thousands

of aircraft at hundreds of miles range, and his

ultimate weapon to end all war -- the Tesla shield,

which nothing could penetrate. However, by

this time no one any longer paid any real attention to the forgotten great genius. Tesla died in

1943 without ever revealing the secret of these

great weapons and inventions.

Scalar Potential interferometer

In the pulse mode,

a single intense 3-dimensional scalar phi-field

pulse form is fired, using two truncated Fourier

transforms, each involving several frequencies, to

provide the proper 3-dimensional shape. After a time delay calculated for the particular target,

a second and faster pulse form of the same shape is fired from the interferometer antennas.

The second pulse overtakes the first, catching it over the target zone and pair-coupling with it

to instantly form a violent EMP of ordinary vector (Hertzian) electromagnetic energy. There is

thus no vector transmission loss between the howitzer and the burst. Further, the coupling time

is extremely short, and the energy will appear sharply in an “electromagnetic pulse (EMP)”

strikingly similar to the 2-pulsed EMP of a nuclear weapon.

This type weapon is what actually

caused the mysterious flashes off the southwest coast of Africa, picked up in 1979 and 1980 by

Vela satellites. The second flash, e.g., was in the infrared

only, with no visible spectrum. Super lightning, meteorite strikes, meteors, etc. do not create this effect. In

addition, one of the scientists at the Arecibo Ionospheric

Observatory observed a wave disturbance -- signature

of the truncated Fourier pattern and the time-squeezing

effect of the Tesla potential wave -- traveling toward

the vicinity of the explosion. With Moray generators as

power sources and multiply deployed reentry vehicles

with scalar antennas and transmitters, ICBM reentry

systems now can become long range “blasters” of the target areas, from thousands of kilometers

distance . Literally, “Star Wars” is liberated by the Tesla technology. And in air attack,jammers and ECM aircraft now become “Tesla blasters.” With the Tesla technology, emitters

become primary fighting components of stunning power.

Directed Energy Weaponry (DEW) with precision to take down world towers in 10.3 seconds

and saw homes in half surgically.

Buried Boneyards

Known as the ‘Catacombs of Paris’, over 6 million skeletons lay beneath the

streets of Paris, France. Some 200 miles of labyrinthine tunnels are believed

to exist. Despite the vast length of the tunneled, underground world, only

a small section of it is open to the public. This tiny

portion (under 1 mile), known as Denfert-Rochereau

Ossuary, has become one of the top tourist attractions

in Paris. The official story for so many bones buried

was that the Parisian Cemeteries were flooded and

overcrowded, yet the population statistics of that time

do not support the narrative. Additionally, there are

only Skulls and Femurs buried there. It is no coincidence that the Yale

Universities Secret Societies, that former President George Bush Sr. was a

member, is also called “Skull and Bones”.

Taking the Paris population numbers into consideration, how do we get 6,000,000 dead people?

Even if they had 250,000 people dying in Paris every 33 years for 500 years straight, we would

only end up with 4,500,000.

Brno Ossuary is an underground ossuary in

Brno, Czech Republic. It was rediscovered in

2001 in the historical centre of the city, partially

under the Church of St. James. It is estimated

that the ossuary holds the remains of over 50,000

people which makes it the second-largest ossuary

in Europe, after the Catacombs of Paris. The

ossuary was founded in the 17th century and was

expanded in the 18th century. It’s been opened

to public since June 2012.

Monastery of San Francisco Catacombs beneath the church

at the Franciscan Monastery in Lima, Peru, there is an ossuary

where the skulls and bones of an estimated 70,000 people

are decoratively arranged. Long forgotten, the catacombs

were rediscovered in 1943 and are believed to be connected

via subterranean passageways to the cathedral and other

local churches.

A bubonic plague allegedly flourished in the crowded

streets of London. Over 15% of London’s population was

wiped out between 1665 and 1666 alone, or some 100,000

people in the space of two years. But where did all these bodies

go? The answer: in tens, if not hundreds of plague pits scattered

across the city and the surrounding countryside. The majority

of these sites were originally in the grounds of churches, but as

the body count grew and the graveyards became overcharged

with dead, then dedicated pits were hastily constructed around

the fields surrounding London.

Wall Street Literally Built

on the Back of Slaves Bones

Wall Street and much of this city’s renowned financial district were built on the burial ground

of Africans. New York’s prosperity stems in large part from the grotesque profits of the Africans

and African enslavement. This is the inescapable conclusion

one draws from the evidence presented in a major exhibition

on “Slavery in New York,” which opened here Oct. 7 and

runs through March 5. Hosted by the New-York Historical

Society, the exhibition is the most impressive display ever

mounted on slavery in the Empire State and in New York

City in particular. Below Trinity Church, Sara Roosevelt Park,

close to the financial centre at Wall Street, extending past

Broadway, southward under New York’s City Hall, and reaching almost to the site of the World

Trade Centre on Manhattan’s southwestern tip, was the area used two hundred years ago to bury

New York City slaves.

Blakey and his forensic archeological team, using lesion morphology and

DNA samples, found a story of enslaved who were forced to engage in backbreaking and excessive

labor. Bone fragments and skeletons mirrored a “work to the death” culture. Most skeletons were

of people under the age of 30 who had injuries that reflected harsh labor condition comprising:

compressed spinal cords, severs muscle tears, bone tears, osteoporosis, and crippling arthritis.

One woman was found with a musket ball lodged in her cranium. Women were found with

their hands folded which was a colonial marking that she was with child. New York became a

very significant seaport and harbor for the Atlantic slave trade. As many as 20% of colonial New

Yorkers were enslaved Africans. New York gained stature and commerce based on trafficking of

human beings—those human being found below the surface New York’s crowded streets.

Destruction of Tartaria’s Structures

SEE PAGE 293-94 ON SCROLL AT LINK

Reichstag Fire ‘put Hitler in Power’

Destruction of Churches

Continues To this Day

Only one year after a devastating fire engulfed Notre

Dame cathedral in Paris, the

fire that broke out in the Gothic

St Peter and St Paul Cathedral,

in Nantes, western France, on

Saturday morning has raised

alarm bells about the security

of France’s 150 cathedrals and

45,000 churches.

Tartarian Genocide On A Mass Scale ~ A Brief History

The Great Fire of London

swept through the central

parts of the city from Sunday,

2 September to Thursday,

6 September 1666. The fire

gutted the medieval City of

London inside the old Roman

city wall. It destroyed 13,200

houses, 87 parish churches, St

Paul’s Cathedral, and most

of the buildings of the City

authorities. It is estimated to

have destroyed the homes

of 70,000 of the city’s 80,000

inhabitant. By the 1660s, London was by far the largest city in Britain, estimated at half a million

inhabitants. The relationship was often tense between the City and the Crown. The City of London

had been a stronghold of republicanism during the Civil War (1642–1651), and the wealthy and

economically dynamic capital still had the potential to be a threat to Charles II, as had been

demonstrated by several republican uprisings in London in the early 1660. The 18-foot (5.5 m)

high Roman wall enclosing the City put the fleeing homeless at risk of being shut into the inferno.

Garry Kasparov ‘s essay “Mathematics of the Past” Kasparov (the chess whiz) is a huge fan of

Fomenko and New Chronology. I found his essay a few days after my simple population math. His

essay uses inferences used by other historians to estimate the population of the “ancient” Roman

empire using data (the size of Rome’s army) from Edward Gibbon’s monumental 18th-century

work The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. The population of “ancient” Rome was likely somewhere between 20 and 50 million. Kasparov writes, “According to J.C. Russell, in the 4th century,

the population of Western Roman Empire was 22 million (including 750 000 people in England

and five million in France), while the population of the Eastern Roman Empire was 34 million.

Kasparov writes:

“It is not hard to determine that there is a serious problem with these numbers. In England,

a population of four million in the 15th century grew to 62 million in the 20th century. Similarly, in France, a population of about 20 million in the 17th century (during the reign of Louis

XIV), grew to 60 million in the 20th century ... and this growth occurred despite losses due

to several atrocious wars. We know from historical records that during the Napoleonic wars

alone, about three million people perished, most of them young men. But there was also the

French Revolution, the wars of the 18th century in which France suffered heavy losses, and

the slaughter of World War I. By assuming a constant population growth rate, it is easy to

estimate that the population of England doubled every 120 years, while the population of

France doubled every 190 years. Graphs showing the hypothetical growth of these two functions are provided in Figure 1. According to this model, in the 4th and 5th centuries, at the

breakdown of the Roman Empire, the (hypothetical) population of England would have been

10,000 to 15,000, while the population of France would have been 170,000 to 250,000. However,

286 The One World Tartarians

according to estimates based on historical documents, these numbers should be in the millions.

It seems that starting with the 5th century, there were periods during which the population

of Europe stagnated or decreased. Attempts at logical explanations, such as poor hygiene,

epidemics, and short lifespan, can hardly withstand criticism. In fact, from the 5th century

until the 18th century, there was no significant improvement in sanitary conditions in Western

Europe, there were many epidemics, and hygiene was poor. Also, the introduction of .rearms

in the 15th century resulted in more war casualties. According to UNESCO demographic

resources, an increase of 0.2 per cent per annum is required to assure the sustainable growth

of a human population, while an increase of 0.02 per cent per annum is described as a demographic disaster. There is no evidence that such a disaster has ever happened to the human

race. Therefore, there is no reason to assume that the growth rate in ancient times differed

significantly from the growth rate in later epochs.”

Kasparov also doubts the ancientness of “ancient” Rome because of the difficulty of mathematical calculations using Roman numerals:”The Roman numeral system discouraged serious

calculations. How could the ancient Romans build elaborate structures such as temples, bridges,

and aqueducts without precise and elaborate calculations? The most important deficiency of

Roman numerals is that they are completely unsuitable even for performing a simple operation

like addition, not to mention multiplication, which presents substantial difficulties.”

Webster’s Oxford Dictionary, many important notions from history, religion and science were

for the first time used in written English. One can clearly see that ‘the whole antique cycle appears

in the English language in the middle of the 16 century as well as the concept of antiquity. We

can see some terms about science - ‘almagest’, ‘astronomy’, ‘astrology’, etc. begin in the 14th or

15th century. If we look for antiquity, ‘Etruscan’ was named in 1706 for the first time, ‘Golden

Age’ in 1505, so think about what this means.:

Almagest 14th century * History 14th century *Antique 1530 century * Iberian 1601 * Arabic

14th century * Indian 14th century * Arithmetic 15th century * Iron Age 1879 * Astrology 14th

century * Koran 1615 * Astronomy 13th century *Mogul 1588 * August 1664 *Mongol 1698 *Bible

14th century * Muslim 1615 *Byzantine 1794 * Orthodox 15th century * Caesar 1567 *Philosophy

14th century * Cathedral 14th century *Platonic 1533 * Catholic 14th century * Pyramid 1549 *

Celtic 1590 * Renaissance 1845 * Chinese 1606 * Roman 14th century *Crusaders 1732 * Roman

law 1660 *Dutch 14th century * Russian 1538 * Education 1531 * Spanish 15th century * Etruscan

1706 * Swedish 1605 * Gallic 1672 * Tartar 14th century * German 14th century * Trojan 14th century * Golden age 1505 * Turkish 1545 * Gothic 1591 * Zodiac 14th century

The third plague pandemic was a major bubonic plague pandemic that began in Yunnan,

China, in 1855 during the fifth year of the Xianfeng Emperor of the Qing dynasty.[1] This episode

of bubonic plague spread to all inhabited continents, and ultimately led to more than 12 million

deaths in India and China, with about 10 million killed in India alone.

Technological Genocide?

Throughout this book I have shown the many

instances of Tartary control and mastery of the

water, air and Earth. The technology we have

today was also available to them, and more. We

have seen millions and millions of bones buried

under cities, and beautiful Tartarian buildings

destroyed without trace. Fire could not bring down

stone and iron, unless the buildings were already

electrified and advanced technologies “flipped”

the highly focused laser directed energy frequencies to bring down the buildings, like what took

down the World Trade Centers. We can see patents

from 1904 using energy to create electromagnetic

rail guns and, certainly Directed Energy Weapons

(DEW) were likely used as well.

Another question has to be asked, is what

happened to the tons and tons of rubble that would

have been accumulated, such as after the World

Fairs. Again, fire is said to be the causal factors, yet

like at the Chicago World Fair, the lands became

a park as did the same after the San Francisco

Pan-Pacific Exhibition of 1915, which is now the

SF Marina and Chrissy Field, unless it was pulverized and then used as land fill and such?

So what happened to the possible billions of Tartaria people? Were star forts built to not only

heal but energetically protect them from the NWO genocidal agendas while keeping the structures in place and still viable?

There is also hard evidence of DEW weapons

patented in 1904. The oldest electromagnetic

gun came in the form of the coilgun, the first

of which was invented by Norwegian scientist Kristian Birkeland at the University of

Kristiania (today Oslo). The invention was

officially patented in 1904, although its development reportedly started as early as 1845.

According to his accounts, Birkeland accelerated a 500-gram projectile to 110 mph.

The Great American Holocaust and

the Jesuit “Reduction” Movement

By the end of the 16th century the Jesuits had already

started a worldwide missionary enterprise which spanned

India, Japan, China, the Congo, Mozambique and Angola

to Brazil, Peru, Paraguay and central Mexico. The presence of the Jesuits in Latin America dates back to 1549,

when the first missionaries arrived in Brazil along with

the governor Tomé de Souza. Through the centuries

Jesuits reached not only South and Central America but

also Africa, Asia, North America and Canada, building

churches, schools and hospitals, running farms and estates, but also, most importantly, proselytizing among native populations. Education and spiritual guidance have always been central to

the Jesuit approach to evangelism.

David Edward Stannard (born 1941) is an American historian and Professor of American Studies

at the University of Hawaii. He wrote “American Holocaust; The Conquest of the New World” in

1992. He chronicles that the genocide against the Native Black Moor population was the largest

genocide in history. The extermination of the Black Moors went roaring across two continents

non-stop for four centuries and consuming the lives of countless tens of millions of people. While

acknowledging that the majority of the indigenous peoples fell victim to the ravages of European

disease, he estimates that almost 100 million died in what he calls the American Holocaust.

After initial contact with the Jesuits, the

story goes that small pox and other diseases

brought over from Europe caused the deaths

of 90 to 95% of the native population of the

in the following 150 years.

Introduced at Veracruz by Cortez’s

Spanish Army in 1520, smallpox ravaged

Mexico in the 1520, possibly killing over

150,000 in Tenochtitlán (the heartland of

the Aztec Empire) alone, and aiding in the

victory of Hernán Cortés over the Aztec

Empire at Tenochtitlan (present-day Mexico

City) in 1521.

In their newly acquired South American ‘dominions’, the Jesuits had adopted

a strategy of gathering native populations

into communities what is now called “Indian

reductions”. The objectives of the reductions

were to subjugate the Natives to exploit slave labor of the native indigenous inhabitants while

also imparting Christianity and European culture. Secular as well as religious authorities created

“reductions” aka genocide, keeping only those necessary for Jesuit needs of service. Reductions

generally were also construed as an instrument to make the Black Moors adopt European lifestyles and values and ‘reduce’ their influence in their native lands.

The Great Fire of New York of 1776 was a

devastating fire that burned through the night

of September 20, 1776, and into the morning of

September 21, on the West Side of what then

constituted New York City at the southern

end of the island of Manhattan.[1] It broke out

in the early days of the military occupation of

the city by British forces during the American

Revolutionary War. The fire destroyed about 10

to 25 percent of the buildings in the city.

The 1835 Great Fire of New York was one

of three fires that rendered extensive damage

to New York City in the 18th and 19th centuries. The fire occurred in the middle of an

economic boom, covering 17 city blocks, killing two people, and destroying hundreds of buildings. At the time of the fire, major water sources including the East River and the Hudson River

were frozen in temperatures as low as –17 °F (–27

°C). Firefighters were forced to drill holes through ice

to access water, which later re-froze around the hoses and

pipes. Attempts were made to deprive the fire of fuel

by demolishing surrounding buildings, but at first

there was insufficient gunpowder in Manhattan.

Later in the evening, U.S. Marines returned with

gunpowder from the Brooklyn Navy Yard and began

to blow up buildings in the fire’s path. An investigation found that a burst gas pipe, ignited by a coal

stove, was the initial source; no blame was assigned.

The fire covered 13 acres (53,000 m2

) in 17 city blocks

and destroyed between 530 and 700 buildings.

The Great New York City Fire of 1845

broke out on July 19, 1845, in Lower

Manhattan, New York City. The fire

started in a whale oil and candle manufacturing establishment and quickly

spread to other wooden structures. It

reached a warehouse on Broad Street

where combustible saltpeter was stored

and caused a massive explosion that

spread the fire even farther. The fire

destroyed 345 buildings in the southern

part of what is now the Financial District.

The Great Boston Fire of 1872 was Boston’s largest fire, and still ranks as one of the most costly

fire-related property losses in American history. The fire was finally contained 12 hours later,

after it had consumed about 65 acres (26 ha) of Boston’s downtown, 776 buildings and much of the

financial district. In 1852, Boston became the first city in the world to install telegraph-based

fire alarm boxes. The boxes served as a fire warning system. If the lever inside of the alarm box

was pulled, the fire department was notified, and the alarm could be traced back to the box via a

coordinate system so that firefighters were dispatched to the correct location. All of the fire alarm

boxes were kept locked from the system’s installation in 1852 until after the Great Fire of 1872

to prevent false alarms. A few citizens in each area of Boston were given a key to the boxes, and

all other citizens had to report fires to the key-holders who could then alert the fire department.

Gas supply lines connected to streetlamps and used for lighting in buildings could not be shut

off promptly. The gas still running through the lines served as fuel to the fire. Many of Boston’s

gas lines exploded due to the fire.

*****

According to the narrative

above, the Great Fire of Boston

went only 12 hours, took out 776

(get it 1776..Boston!) and much of

the financial district and the fire departments were notified by telegraph to the fire stations by

those who had keys to the telegraph based fire alarm systems

and responded with horse and buggy in just 20 minutes! And

much of Boston was fed by gas lines connected to streetlamps…

Oh Really?

San Francisco Earthquake 1906 & Fire…

See page 302 @ the link for DEW Comparisons

Tartary Genocide in Russia ~

40-100 million Killed from 1920 - 1945

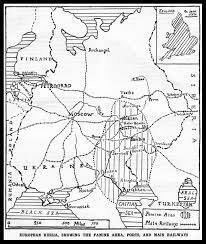

Soviet Famine 1921–1922

There was a famine in the Tatar Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic in 1921 to 1922 as a

result of war communist policy. The famine deaths of 2 million Tatars in Tatar ASSR and in Volga/Ural region in 1921–1922 was catastrophic as half of Volga Tatar population in USSR died. This

famine is also known as “terror-famine” and “famine-genocide” in Tatarstan. The Soviets settled

ethnic Russians after the famine in Tatar ASSR and in Volga-Ural region causing the Tatar share

of the population to decline to less than 50%. All-Russian Tatar Social Center (VTOTs) has asked

the United Nations to condemn the 1921 Tatarstan famine as Genocide of Muslim Tatars. The

1921–1922 famine in Tatarstan has been compared to Holodomor in Ukraine.

Soviet famine of 1932–33 was a major

famine that killed millions of people

in the major grain-producing areas of

the Soviet Union, including Ukraine,

Northern Caucasus, Volga Region and

Kazakhstan, the South Urals, and West

Siberia. The exact number of deaths

is hard to determine due to a lack of

records. Stalin and other party members

had ordered that kulaks were “to be

liquidated as a class” and so they became

a target for the state. The richer, landowning peasants were labeled “kulaks”

and were portrayed by the Bolsheviks

as class enemies, which culminated in

a Soviet campaign of political repressions, including arrests, deportations,

and executions of large numbers of the

better-off peasants and their families in 1929–1932. The Holodomor moryty holodom, ‘to kill by

starvation’, was a man-made famine in Soviet Ukraine from 1932 to 1933 that killed millions

of Ukrainians. It is also known as the Terror-Famine and Famine-Genocide in Ukraine, and

sometimes referred to as the Great Famine or the Ukrainian Genocide of 1932–33. It was part

of the wider Soviet famine of 1932–33, which affected the major grain-producing areas of the

country. During the Holodomor, millions of inhabitants of Ukraine, the majority of whom were

ethnic Ukrainians, died of starvation in a peacetime catastrophe unprecedented in the history

of Ukraine. Since 2006, the Holodomor has been recognized by Ukraine and 15 other countries

as a genocide of the Ukrainian people carried out by the Soviet government. Early estimates of

the death toll by scholars and government officials varied greatly. According to higher estimates,

up to 12 million[15] ethnic Ukrainians were said to have perished as a result of the famine.

The Carpet Bombing over and over

and over by US Allies in 1945

After the Tartarian defeat, all the

ancient buildings “destroyed by wars”

were miraculously “rebuilt” from the

years “1870s” by nonexistent architects

whose portraits are a pastiche. Fantasies like “was destroyed by fire in 1895

and rebuilt in 1901” are written to hide

the advanced and superior technology

present in the constructions of Tartary

long before the 9th century. Some wars,

bombings, or great fires of the past may

be historical falsehoods, repeated in

3 different layers like 1776, 1812 and

1870s. In Dresden, for example, there

would have been a battle in 1813, revolts

that damaged the city in 1848 and 1863,

and severe bombing in February 1945.

According to Official History, 90% of

the city center was destroyed. But this

is not entirely true. The main buildings

of the old citadel were spared.[Eisenhower should have been charged as a war criminal for what he did AFTER Germany's surrender dc]

There was a selective bombing that targeted residential dwellings as well as factories and

military facilities. Dresden was a huge Star Fortress and capital of the Free State of Saxony, which

did not obey to the “Pope” and to the new emperors. The region had been entirely colonized by

Aryan and housed over 600,000 war refugees whom the Invaders had an interest in exterminating.

Dresden was an important economic center, with 127 factories and military facilities that could

house 20,000 people. The city’s skyline continues exactly as it was in the 1800s and probably still

draws energy from the ether. But the ancient inhabitants were gone to give place to the invaders.

This building in Dresden, for example, is a huge Tartarian power

station, transformed into a mosque by Grey Men acting on behalf of

Invading NWO Parasites. Even so, it still retains the red and white

colors of Tartary that designated the main function of these structures.

As an American prisoner of war, Kurt Vonnegut witnessed the

firebombing of Dresden, Germany in 1945 from the cellar of a slaughterhouse, an experience he later recounted in his most celebrated

novel, “Slaughterhouse-Five.” described the event as “the greatest

massacre in European history.” A four-night aerial bombing attack by

the Americans and British dropped more than 3,900 tons of explosives

on the city. Mr.Vonnegut described the scene afterward as resembling

“the surface of the moon.” There were so many corpses, he wrote,

that German soldiers gave up burying them and simply burned them

on the spot with flame-throwers.

see more had to be DEW PICS @ PAGE 306 on the scroll at the link below

Appendix I

Tartarian Architecture

Worldwide aka Gothic/

Renaissance

Argentina

Cathedral of Bariloche

Cathedral of La Plata

Cathedral of Luján

Cathedral of Mar del Plata

Australia

Government House, Sydney

Scots’ Church, Melbourne

Vaucluse House Sydney Regency Gothic.

Sydney Conservatorium of Music, the old Government

stable block.

Government House, Sydney

St. Andrew’s Cathedral, Sydney

St. Mary’s Cathedral, Sydney

Sydney University, the main building, commenced

1850s, extended 20th century

St Patrick’s Cathedral, Melbourne

St. Paul’s Cathedral, Melbourne

Melbourne University – Main Building, Newman College and Ormond College

The Collins Street group in Melbourne – Rialto buildings, Former Stock Exchange, Gothic Bank,

Goode House and Olderfleet buildings and Safe Deposit Building

St David’s Cathedral, Hobart

Government House, Hobart

Perth Town Hall

Newington College, founders block

Church of the Apostles, Launceston

Austria

Votivkirche, Vienna, 1856–79

Rathaus, Vienna, 1872–83

New Cathedral (Cathedral of the

Immaculate Conception), Linz, 1862–1924

Vier-Evangelisten-Kirche, Arriach,

Johanneskirche, Klagenfurt

Evang. Kirche, Techendorf

Evangelische Kirche im Stadtpark, Villach

Nikolai-Kirche, Villach

Filialkirche hl. Stefan, Föderlach (Wernberg)

Marienkirche, Berndorf, Lower Austria

Bründlkapelle, Dietmanns

Sisi Chapel located in the Sievering area of the Viennese district of Döbling near the Vienna Woods

Saint John the Evangelist church Aigen, Upper Austria

Pfarrkirche, Bruckmühl, Upper Austria

Evang. Pfarrkirche A.B., Steyr, Upper Austria

Pfarrkirche Mariä Himmelfahrt,

Mauerkirchen, Upper Austria

Filialkirche Heiliges Kreuz Friedhof,

Münzbach, Upper Austria

Barbados

Parliament of Barbados, west-wing

completed 1872,

east-wing in 1873.

Belgium

Sint-Petrus-en-Pauluskerk, Ostend

Maredsous Abbey, 1872–1892

Loppem Castle, 1856–1869

Church of Hunnegem, paintings 1856–1869

Basilica of Our Lady, Dadizele, 1857–1867[citation needed]

Sint-Petrus-en-Pauluskerk, Ostend, 1899–1908

Church of Our Lady of Laeken, Brussels, 1854–1909

Mesen castle, Lede.

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Cathedral of Jesus’ Heart, Sarajevo

Cathedral of Jesus’ Heart, Sarajevo

Brazil

Church of Our Lady of Purification, Bom Princípio,

1871

Sanctuary of Our Lady Mother of

Humanity (Caraça), Minas Gerais, 1876

Basilica of the Immaculate Conception,

Rio de Janeiro, 1886

Cathedral of Our Lady of Exile, Jundiaí, 1890

Cathedral of Santa Teresa, Caxias do Sul, 1899

Crypt of São Paulo

Cathedral

St. Peter of Alcantara

Cathedral, Petrópolis, 1884–1969

Church of Saint Peter, Porto Alegre, 1919

Cathedral of Our Lady of Boa Viagem, Belo Horizonte, 1923

Church of Santa Rita, Santa Rita do Passa Quatro

Church of The Holy Sacrament and

Santa Teresa, Porto Alegre, 1924

São Paulo Sé Cathedral (Catedral da Sé de São Paulo),

São

Paulo, 1912–1967

Premonstratensian Seminary Chapel,

Pirapora do Bom

Jesus, 1926

Sanctuary of Santa Teresinha, Taubaté, 1929

São João Batista Cathedral (Catedral São João Batista), Santa

Cruz do Sul, 1928–1932

Church of Our Lady of the Glory, Sinimbu, 1927

Basilica of Santo Antonio, Santos, 1929

Basilica of Our Lady of the Rosary, Caieiras, 2006

Basilica of Our Lady of the Rosary of Fatima,

Embu das

Artes, São Paulo, 2004

Canada

Parliament Hill, Ottawa, Ontario

Parliament Hill, Ottawa, Ontario, 1878

Notre-Dame Basilica, Montreal, Quebec, 1829

St. James’ Cathedral, Toronto, Ontario, 1853

Cathedral of St. John the Baptist

St. John’s, Newfoundland,

1847–85

Church of Our Lady Immaculate, Guelph, Ontario, 1888

Currie Hall, Royal Military College of Canada,

Kingston, Ontario, 1922

College Building, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan (1913)

Little Trinity Anglican Church, 1843,

Toronto, Ontario – Tudor

Gothic revival

Church of the Holy Trinity (Toronto), 1847, Toronto, Ontario

St. Dunstan’s Basilica 1916, Charlottetown, PEI

Hart House at the University of Toronto,

1911–1919, Toronto,

Ontario

1 Spadina Crescent, at the University of Toronto,

Toronto,

Ontario, 1875

Burwash Hall at Victoria University in the

University of

Toronto, Toronto, Ontario

Cathedral of St. John the Baptist, St. John’s

St. Patrick’s Church, St. John’s

St. Peter’s Cathedral (London), London, Ontario, 1885

St. Patrick’s Basilica, Montreal, Montreal, 1847

Ottawa Normal School, Ottawa, Ontario, 1874

St. Patrick’s Basilica (Ottawa), Ottawa, Ontario, 1875

First Baptist Church (Ottawa), Ottawa, Ontario, 1878

Confederation Building (Ottawa), Ottawa, Ontario, 1931

Christ Church Cathedral, Montreal

St. Michael’s Basilica, Chatham, New Brunswick

St. Mary’s Basilica (Halifax),

Halifax Regional Municipality,

Nova Scotia, 1899

St. Michael’s Cathedral, Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, 1845

Church of the Redeemer (Toronto), Toronto, Ontario, 1879

St. James Anglican Church, Vancouver, British Columbia

Bathurst Street Theatre, Toronto, Ontario, 1888

Bloor Street United Church, Toronto, Ontario, 1890

Casa Loma, Toronto, Ontario, 1914

Chile

Federico Santa María Technical University, Valparaíso 1931

Church of the Sacred Heart, Valparaíso

Church of the Twelve Apostles, Valparaíso, 1869

Vergara Hall (Venetian Gothic), Viña del Mar, 1910

China

Sacred Heart Cathedral, Canton, China, 1863–1888

Church of the Saviour, Beijing, China

St. Ignatius Cathedral, Shanghai, China

Cathedral of St Joseph, Chongqing, China

Sacred Heart Cathedral, Jinan, China

Saint Dominic’s Cathedral, Fuzhou, China

Sacred Heart Cathedral, Shengyang, China

St. John’s Cathedral, Hong Kong, China

St. Theresa’s Cathedral, Changchun, China

National Shrine and Minor Basilica of

Our Lady of Sheshan,

Shanghai, China

Xizhimen Church, Beijing, China

Croatia

Castle Trakošćan, 1886

Hermann Bollé, Monumental cemetery

Mirogoj, Zagreb,

1879–1929

Hermann Bollé, Zagreb cathedral, 1880-

Costa Rica

Iglesia de Coronado, San Jose

Saint Venceslav Cathedral in Olomouc,

Czech Republic

Basilica of St Peter and St Paul, Prague

Completion of St. Vitus Cathedral, Prague, 1870–1929

Completion of Saint Wenceslas cathedral,

Olomouc, 1883–92

Hluboká Castle

Herholdt’s Copenhagen University Library (1861)

Denmark

St. Ansgar’s Cathedral, Copenhagen (1840–42)

University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, 1835

Copenhagen University Library, Copenhagen, 1857–61

St. John’s Church, Copenhagen,

Nørrebro, Copenhagen, 1861

St. James’s Church, Østerbro, Copenhagen, 1876–78

Church of Our Lady, Aarhus, 1879–80

St. Alban’s Church, Copenhagen, 1885–87

Equatorial Guinea

St. Elizabeth’s Cathedral, Malabo, 1897–1916

Cathedral of Santa Isabel of Malabo

Finland

St. Henry’s Cathedral, Helsinki, 1858–1860

Ritarihuone, Helsinki, 1862

Heinävesi Church, Heinävesi, 1890–1891

St. John’s Church, Helsinki, 1888–1893

Mikkeli Cathedral, Mikkeli, 1896–1897

Joensuu church, Joensuu, 1903

Basilica of St. Clotilde in Paris, France

France

Temple Saint-Étienne, Mulhouse

Basilica of St. Clotilde, Paris

Église Saint-Ambroise (Paris)

Église Saint-Georges, Lyon

Jesuit Church, Molsheim

St. Paul’s Church, Strasbourg

Basilica of the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Lourdes

Germany

New Town Hall in Munich, Germany

Nauener Tor, Potsdam, 1755

Gothic House, Dessau-Wörlitz Garden Realm, 1774

Friedrichswerdersche Kirche, Berlin, 1824–30

Castle in Kamenz (now Kamieniec Ząbkowicki in Poland), 1838–65

Burg Hohenzollern, 1850–67

Completion of Cologne Cathedral, 1842–80

New Town Hall, Munich, 1867–1909

St. Agnes, Cologne, 1896–1901

Hungary

Sacred Heart Church, Kőszeg

Hungarian Parliament Building, Budapest

Matthias Church, Budapest

India

Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, Mumbai

San Thome Basilica, Chennai, India

St Paul Cathedral, Kolkata, India

Kolkata High Court, Kolkata, India

Mutiny Memorial, New Delhi, India

St. Stephen’s Church, New Delhi, India

Our Lady of Ransom Church, Kanyakumari, India

Cathedral of the Holy Name, Mumbai, India

Mount Mary Church, Bandra, Mumbai, India

Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, Mumbai, India

University of Mumbai, Mumbai, India

Bombay High Court, Mumbai, India

Wilson College, Mumbai, India

David Sassoon Library, Mumbai, India

St. Philomena’s Church, Mysore, India

Medak Cathedral. Medak. (Telangana). (India)

Indonesia

Church of our Lady Assumption, Jakarta

Church of our lady Assumption, Jakarta, Indonesia

(Locally known

as Gereja Katedral Jakarta)

Ursula Chapel, Jakarta, Indonesia

Church of the birth of our Lady Mary, Surabaya, Indonesia

St. Peter’s Church, Bandung, Indonesia

St. Joseph’s Church, Semarang, Indonesia

St. Fransiskus Chapel, Semarang, Indonesia (located at Ordo St.

Fransiskus (OSF) Cloister)

St. Mary the Virgin Church, Bogor, Indonesia

Regina Pacis Chapel, Bogor, Indonesia

Sacred Heart of Jesus Church, Malang, Indonesia (Locally known

as Gereja Kayutangan)

Sayidan Church, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Ireland

St John’s Cathedral, County Limerick, 1861

St. Eunan’s Cathedral, Letterkenny, County Donegal,

Saint Finbarre’s Cathedral, Cork, 1870

Saints Peter and Paul’s Church, Cork, 1866

St Mary’s Cathedral, Killarney, County Kerry,

1842–55

St. Aidan’s Cathedral, Enniscorthy, County

Wexford, 1843

St Mary’s Cathedral, Tuam, County Galway, 1878

St. Mary’s Cathedral, Kilkenny, County, Kilkenny,

1857

Italy

Liguria

Castello d’Albertis, Genoa.

Chiesa di San Teodoro, Genoa, 1870

chiesa protestante di Genova, Genoa.

chiesa anglicana All Saints Church,

Bordighera, in the Province of Imperia.

chiesa di Santo Spirito e Concezione, Zinola/Savona, 1873

Piedmont

Castello di Pollenzo, Brà (near Cuneo), Piedmont.

Chiesa di Santa Rita, Turin, early 20th century.

Borgo Medioevale, Turin.

Tempio Valdese, Turin, 1851–53

Veneto

Caffè Pedrocchi (or Pedrocchino), Padua,

mixed parts of

gothic and classical styles.

Molino Stucky, Venice.

chiesa di San Giovanni Battista, San Fior, in

the Province

of Treviso, 1906–1930

Palazzetto Stern, Venice.

Villa Herriot, Venice.

Casa dei Tre Oci, Venice.

Trieste

Chiesa Evangelico Luterana, Trieste, 1871–74

Notre Dame de Sion, Trieste, 1900

Tuscany

Florence Cathedral, the facade only.

Chiesa del Sacro Cuore (Livorno), Livorno (Leghorn),

1915

Palazzo Aldobrandeschi, Grosseto, 1903

chiesa Valdese, Florence.

chiesa Episcopale Americana di Saint James,

Florence, early 20th century.

Tempio della Congregazione Olandese Alemanna,

Livorno, 1862–1864

Lazio

Chiesa di Santa Maria del Rosario in Prati, Rome, 1912–16

Church of Sacro Cuore del Suffragio, Rome, 1917

chiesa del Sacro Cuore, Grottaferrata, in the Province of Rome,

1918–1928

Chiesa Anglicana Episcopale di San Paolo

entro le Mura, Rome

Chiesa di Ognissanti (chiesa anglicana di Roma),

Rome, 1882

Molise

Santuario dell’Addolorata, Castelpetroso, 1890–1975

Campania

Chiesa di Santa Maria stella del mare,

Naples, early 20th century.

Castello Aselmeyer, Naples.

Anglican Church of Naples, Naples, 1861–1865

Chiesa Luterana, Naples, 1864

Sardinia

City Hall (Cagliari), Cagliari, 1899

Sicily

Chiesa di Santa Maria della Guardia, Catania, 1880

chiesa anglicana di Palermo, Palermo, 1875

Japan

Ōura Church, Nagasaki

Korea

Cathedral Church of the Virgin Mary of the Immaculate Conception, Myeongdong

Chunghyeon Church, Seoul[7]

Lithuania

Church in Švėkšna

Beržėnai Manor

Belltower of the Church of St. Anne in Vilnius

Chapel in Rasos Cemetery

Church of the Ascension of Christ in Kupiškis

Church of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary in Palanga

Church of the Assumption of the

Blessed Virgin Mary in

Salantai

Church of the Birth of the

Blessed Virgin Mary in Nemunaitis

Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary

of the Scapular in

Druskininkai

Church of St. Anne in Akmenė

Church of St. Anthony of Padua in Birštonas

Church of St. Casimir in Kamajai

Church of St. James the Apostle in Švėkšna

Church of St. John the Baptist in Ramygala

Church of St. Joseph in Karvis

Church of St. George in Vilkija

Church of the Name of Blessed Virgin Mary in Sasnava

Church of the Holy Trinity in Gruzdžiai

Church of the Holy Trinity in Jurbarkas

Church of the Holy Trinity in Pabiržė

Church of the Holy Trinity in Tverečius

Church of St. Matthias in Rokiškis

Church of St. Matthew the Apostle in Anykščiai

Church of St. Stanislaus the Bishop in Kazitiškis

Evangelical Lutheran Church in Juodkrantė

Evangelical Lutheran Church in Nida

Evangelical Lutheran Church in Šilutė

Lentvaris Manor

Paliesiai Manor

Raduškevičius Palace

Raudone Castle

Tyszkiewicz family Mausoleum and Chapel in Kretinga

Malaysia

St Michael’s Institution, Ipoh, Malaysia

St. Xavier Church, Malacca, Malaysia[8]

Holy Rosary Church, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia[9]

Mexico

Chapultepec Castle, Mexico City

Cathedral of Our Lady of Guadalupe, Zamora, Michoacán

Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral

Palacio de Correos de Mexico

La Parroquia Church of St. Michael the Archangel,

San Miguel de Allende

Templo Expiatorio del Santísimo Sacramento, Jalisco

Templo Expiatorio del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús,

León, Guanajuato

Parroquia de San Jose Obrero, Arandas Jalisco

Myanmar

St. Mary Cathedral, Yangon, Myanmar

Holy Trinity Cathedral, Yangon, Myanmar

St. Joseph Church, Mandalay, Myanmar

New Zealand

Christchurch Cathedral

Canterbury Museum, Christchurch.

(Benjamin Mountfort architect)

Christchurch Arts Centre, Christchurch (Mountfort)

Christchurch Cathedral, Christchurch

(George Gilbert Scott and Mountfort)

Canterbury Provincial Council Buildings,

Christchurch (Mountfort)

Christ’s College, Christchurch, Christchurch

Victoria Clock Tower, Christchurch (Mountfort)

Dunedin Town Hall, Dunedin, 1878–1880. (Robert Lawson)

First Church, Dunedin 1867–1873. (Lawson)

Knox Church, Dunedin 1874-1876.(Lawson)

Larnach Castle, Dunedin, 1867–1887. (Lawson)

Old St. Paul’s, Wellington (Frederick Thatcher)

St. Joseph’s Cathedral, Dunedin, 1879-1886.(Francis Petre)

Otago Boys’ High School, Dunedin 1883–1885. (Lawson)

Seacliff Lunatic Asylum, Dunedin, 1884–1887. (Lawson)

University of Otago Clocktower complex,

Dunedin, 1878–1922.

(Maxwell Bury)

University of Otago Registry Building,

Dunedin, 1879–1922. (Bury)

Lyttelton Timeball Station, Lyttelton. (Thomas Cane)

Norway

Oscarshall, Oslo, 1847–1852

Sagene Church, Oslo, 1891

Tromsø Cathedral, in wood, Tromsø, Norway, 1861

Pakistan

Government College University, Lahore, Pakistan

Cathedral Church of the Resurrection, Lahore, Pakistan

St. Patrick Cathedral, Karachi, Pakistan

St Andrew’s Church, Karachi, Pakistan

Philippines

San Sebastian Church, Manila, 1891

St. Anne’s Parish Church / Molo Church, Iloilo, 1795

Montserrat Abbey San Beda University, Manila, 1926

Archdiocesan Shrine of Espiritu Santo,

Santa Cruz, Manila, 1932

Ellinwood Malate Church, Malate, Manila, 1936

Manila Central United Methodist Church,

Ermita, Manila, 1937

Iglesia ni Cristo Lokal ng Washington,

Sampaloc, Manila, 1948

Knox United Methodist Church, Santa Cruz, Manila, 1953

Poland

19th-century palace in Opinogóra

houses the Museum of

Romanticism.

Gothic House in Puławy, 1800–1809

Potocki mausoleum located

at the Wilanów Palace, 1823–1826

Lublin Castle, 1824–1826

Krasiński Palace in Opinogóra Górna, 1828–1843

Kórnik Castle, 1843–1861

Blessed Bronisława Chapel in Kraków, 1856–1861

Collegium Novum of the Jagiellonian University

in Kraków, 1873–1887

Karl Scheibler’s Chapel in Łódź, 1885–1888

Cathedral in Siedlce, 1906–1912

Temple of Mercy and Charity in Płock, 1911–1914

Russia

The Grand Palace in Tsaritsyno

Gothic Chapel, Peterhof

Chesme palace church (1780), St Petersburg

Tsaritsyno Palace, Moscow

Nikolskaya tower of Moscow Kremlin, Moscow

St. Mary Cathedral, Moscow

St. Andrew’s Anglican Church, Moscow (1884)

TSUM, Moscow

Singapore

St Andrew’s Cathedral on North Bridge Road, Singapore

Church of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary

on Serangoon,

Singapore

Spain

Astorga Episcopal Palace, Astorga

Casa de los Botines, León

Cathedral of San Cristóbal de La Laguna,

San Cristóbal de La Laguna

Facade and spire of Cathedral of Santa Eulalia, Barcelona

Temple Expiatori del Sagrat Cor, on Tibidabo hill, Barcelona

Gothic Quarter, Barcelona

Sobrellano Palace, Comillas

Cathedral of María Inmaculada of Vitoria

Butrón Castle

San Sebastián Cathedral

Sweden

Neo gothic buildings erected during 19th or 20th century

St. John’s church, Stockholm

St. Peter and St. Sigfrids anglican church, Stockholm

Gustavus Adolphus church, Stockholm

Oscar church, Stockholm

St. George’s greek orthodox cathedral, Stockholm

Nacka church, Nacka, Stockholm

Gustavsberg church, Gustavsberg, Stockholm

Taxinge church, Taxinge

Matthew’s church, Norrköping

Oscar Fredrik’s church, Gothenburg

Örgryte new church , Gothenburg

St. John church, Gothenburg

St. Andrew’s anglican church, Gothenburg

Gustavus Adolphus’s church, Borås

Trollhättan church, Trollhättan

Smögen church, Smögen

Lysekil church, Lysekil

Rudbeck school, Örebro

Olaus Petri church, Örebro

Åtvid new church, Åtvidaberg

Kristinehamn church, Kristinehamn

Luleå cathedral, Luleå

Umeå city church, Umeå

Gustavus Adolphus’s church, Sundsvall

Oviken new church, Oviken

Church of all saints, Lund

the University Library, Lund

Cathedral School, Lund

Norra Nöbbelöv church, Lund

Eslöv church, Eslöv

Svedala church, Svedala

Billinge church, Billinge

Källstorp church, Källstorp

Asmundtorp church, Asmundtorp

Nosaby church, Nosaby

Österlöv Church, Österlöv

Östra Klagstorp church, Östra

Klagstorp

Sofia church, Jönköping

Arlöv church, Arlöv, Malmö

Bunkeflo church, Bunkeflo, Malmö

Limhamn church, Limhamn, Malmö

Gustavus Adolphus’s church,

Helsingborg Helsingborg court house,

Helsingborg Gossläroverket (Grammar School for boys),

Helsingborg Medieval and other buildings

influenced by neo gothic renovation

St. Nicolai church, Trelleborg Floda church, Flodafors

Uppsala cathedral, Uppsala Skara Cathedral, Skara

Linköping Cathedral, Linköping

St. Nicolai church, Örebro

Klara church, Stockholm

Riddarholmen church, Stockholm

Malmö court house, Malmö

Ukraine

St. Nicholas Roman Catholic Cathedral, Kiev

Roman Catholic Cathedral in Kharkiv

Church of St. Olha and Elizabeth in Lviv,

United Kingdom England

Clock tower of St. Pancras railway station in London, United

Kingdom

Albert Memorial, London, 1872

All Saints’ Church, Daresbury, Cheshire, 1870s,

the tower is

medieval

All Saints Church, Leamington Spa, Warwickshire, 1843

All Saints Church, Margaret Street, London

Bristol Cathedral, Bristol, the nave and west front

Broadway Theatre, Catford, London, 1928–32

Charterhouse School, Godalming, Surrey

Church of St Mary the Virgin, Reculver, Kent, 1876–78

Downside Abbey, Somerset, c.1882–1925

33-35 Eastcheap, City of London, 1868

Fonthill Abbey, Wiltshire, 1795–1813 (no longer survives)

Guildford Cathedral, Guildford

John Rylands Library, Manchester, 1890–1900

Keble College, Oxford, 1870

Liverpool Cathedral, Liverpool

Manchester Town Hall, Manchester, 1877

The Maughan Library, City of London, 1851–1858

Northampton Guildhall

Palace of Westminster (Houses of Parliament),

London, begun

in 1840

Royal Chapel of All Saints, Windsor Great Park,

Berkshire,

remodelled in 1866

Royal Courts of Justice, London

St. Chad’s Cathedral, Birmingham

St James the Less, Pimlico, London

St Oswald’s Church, Backford, Cheshire,

the nave 1870s, the tower and chancel are medieval

St Walburge’s Church, Preston

St Pancras railway station, London, 1868

South London Theatre, London

Tower Bridge, London

Truro Cathedral, Cornwall

Tyntesfield, Somerset, 1863

Southwark Cathedral, Southwark, London, the nave

Strawberry Hill, London, begun in 1749

Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Oxford

Woodchester Mansion, Gloucestershire, c.1858–1873

Wills Memorial Building at the University of Bristol, Bristol,

1915–1925

Scotland

Scott Monument, Edinburgh

Barclay Church, Edinburgh, Scotland, 1862–1864

St Mary’s Cathedral, Edinburgh (Episcopal), from 1874

Scott Monument, Edinburgh, Scotland, begun in 1841

Gilbert Scott Building, University of Glasgow campus, Glasgow,

Scotland, (the second largest example of Gothic Revival

architecture in the British Isles), 1870

Kelvinside Hillhead Parish Church, Observatory Road/Huntly

Gardens, West End, Glasgow. Opened 1876. Based on the

famous Sainte Chapelle, Paris

Wallace Monument

Wales

Hawarden Castle (18th century), Hawarden

Gwrych Castle, Abergele, 1819

Penrhyn Castle, Gwynedd, 1820–45

Cyfarthfa Castle, Merthyr Tydfil, 1824

Treberfydd, near Brecon, 1847−50

Bodelwyddan Castle, Bodelwyddan, Denbighshire, 1850s, with further alterations in the 1880s

Hafodunos, near Llangernyw, 1861–6

Cardiff Castle, Glamorgan, 1866–9

Castell Coch, Glamorgan, 1871

United States

Alabama

Lanier High School (Montgomery, Alabama), Montgomery, Alabama

California

Hearst Castle, San Simeon, California

Cathedral Building, Oakland, California, 1914

Grace Cathedral, San Francisco, 1928–1964.

St. Dominic’s Roman Catholic Church, San Francisco, 1928

All Saints Episcopal Church (Pasadena, California),

church 1926, rectory 1931.

First Congregational Church of Los Angeles,

Los Angeles, California 90020, 1931

Connecticut

Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut

Harkness Tower, 1917–21

Hall of Graduate Studies, Yale Law School

Payne Whitney Gymnasium

Residential colleges

Sterling Memorial Library

Florida

Several buildings on the University of Florida campus, Gainesville, Florida

Georgia

Congregation Mickve Israel, Savannah, Georgia, 1876–78. A

rare example of a Gothic revival synagogue.

Illinois

Tribune Tower, Chicago, Illinois, completed in 1925

University of Chicago

Rockefeller Chapel

other campus buildings

Indiana

Basilica of the Sacred Heart, Notre Dame, Indiana, 1882

Louisiana

Christ Church Cathedral, New Orleans,

New Orleans, Louisiana, 1886.

Old Louisiana State Capitol, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 1849.

St. Patrick’s Church (New Orleans, Louisiana),

New Orleans, Louisiana, 1837.

Maryland

The Baltimore City College (public high school), Baltimore,

Maryland, founded 1839, erected 1926–1928, third oldest

public high school in America, nicknamed “The Castle

on the Hill”, at 33rd Street and The Alameda.

Massachusetts

Boston College, Boston, Massachusetts

Bapst Library, 1908

Michigan

Woodward Avenue Presbyterian Church,

Detroit, Michigan,

1911

Mississippi

St. Mary’s Episcopal Chapel in

Adams County, Mississippi,

1837

Missouri

Brookings Hall and several buildings on the Washington

University campus, St. Louis, Missouri

St. Francis de Sales Church (St. Louis, Missouri), the second

largest church in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of

St. Louis

New Jersey

Cathedral Basilica of the Sacred Heart

(Newark, New Jersey) 1954

Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey

Princeton University Chapel, 1925–1928

Princeton University Graduate College

Whitman College House

Several buildings on the Seton Hall University campus, South Orange, New Jersey

New York

American Museum of Natural History, Manhattan, 1877

Saint Ignatius of Antioch Episcopal Church, Manhattan, 1902

St. Patrick’s Cathedral, New York City, 1858–78

Woolworth Building, New York City, 1910–13

Trinity and U.S. Realty Building, New York City, 1907

New York Life Insurance Building, New York City, 1928

Liberty Tower, New York City, 1909

Public School 166 in Manhattan, New York City, 1898

McGraw Tower, Uris Library, Willard Straight Hall, and other buildings on the Cornell University

campus in Ithaca, New York.

Several buildings of the Fordham University campus in The Bronx including structures as recently

constructed as 2000.