The One World Tartarians

The Greatest Civilization

Ever to Be Erased From History

James W. Lee

Chapter 17

Grand Exhibitions & Amazing

Amusement Parks

Note that most of these Great Exhibitions and Amusement Parks only were erected,

opened in less than one year at many sites, than were burned by fires, many immediately thereafter. Sometimes by design and sometimes by ‘accident’. There were over 75

world exhibitions before 1870! (Please see Appendix II for the list of the hundreds of exhibitions

up to 1930).

As you will read, the exhibitions worldwide were grandiose, extravagant, attended by millions,

and brought people and resources from all around the world. This was likely the remnants of

the fun, fun, fun loving Tartarian’s. Also, the worldwide participation from as far away as the

Samoa, Alaska, China, South America, Hawaii etc., means they would have had to sail all their

equipment across the Oceans to come to these huge events. And how did they communicate with

the world’s people to get them to come and arrange for their travel, lodging and meet them at

the docks, then carry and set up the incredibly elaborate displays…..all using horse and buggy

to build out the exhibitions.

At the Chicago World’s Exhibition in 1893 it is claimed that ¼ of the entire population of the

USA at that time had attended the fair. Again, how were they notified, where did they lodge

and get transported? You will see some of the most amazing structures for education, community

and FUN! The exhibition’s excuse for hosting ranged from celebrating the opening of the Panama

Canal, to the harvesting of electricity to the celebration of the Louisiana Purchase. Many times the

event builders had to dredge record amounts of dirt and fill to hold the exhibitions on, or near

water. Water, we will learn, is an energy conductor and was necessary to power the exhibitions

to light them up at nighttime.

I focused on providing narratives and images to the exhibitions from the 1850 -1930 because

this was still considered before commercial airplanes, national highways and large-scale engines

to move great stones and steel and such. It is also very interesting to note that during this time

period there were 22 “International Exhibitions” being held during great economic hardships and

even World War I that went from July 1914 to November 1918. Now how was this even possible

given there was a World War going on at the same exact time.

• 1914 – London – Anglo-American Exhibition

• 1914 – Malmö, Sweden – Baltic Exhibition

•1914 Boulogne-sur-Mer, France – International Exposition of Sea Fishery Industries

• 1914 – Lyon, France – Exposition internationale urbaine de Lyon

• 1914 – Tokyo, Japan – Tokyo Taisho Exposition

• 1914 – Cologne, Germany – Werkbund Exhibition (1914)

• 1914 – Bristol, United Kingdom – International Exhibition (1914)[82]

• 1914 – Nottingham, United Kingdom – Universal Exhibition (1914) (work begun on

site 1913 but never held)

• 1914 – Semarang, Dutch East Indies – Colonial Exhibition of Semarang (Colonial

Exposition)

• 1914 – Kristiania, Norway – 1914 Jubilee Exhibition (Norges Jubilæumsudstilling)

• 1914 – Baltimore, United States – National Star-Spangled Banner Centennial

Celebration[85]

• 1914 – Genoa, Italy – International exhibition of marine and maritime hygiene

• 1915 – Casablanca, Morocco – Casablanca Fair of 1915

• 1915 – San Francisco, United States – Panama–Pacific International Exposition Palace

of Fine Arts

• 1915 – Panama City, Panama – Exposición Nacional de Panama (1915)

• 1915 – Richmond, United States – Negro Historical and Industrial Exposition (1915)

• 1915 – Chicago, United States – Lincoln Jubilee and Exposition (1915)

• 1915–1916 – San Diego, United States – Panama–California Exposition

• 1916 - Wellington, New Zealand - British Commercial and Industrial Exhibition

• 1918 – New York City, United States – Bronx International Exposition of Science,

Arts and Industries[79]

• 1918 – Los Angeles, United States – California Liberty Fair (1918)

There was also great economic crisis’ and hardships during the time of the World Exhibitions.

* Panic of 1857, a U.S. recession with bank failures

* Panic of 1866, was an international financial downturn that accompanied the failure of

Overend, Gurney and Company in London

* Great Depression of British Agriculture (1873–1896)

* Long Depression (1873–1896)

* Panic of 1873, a US recession with bank failures, followed by a four-year depression with

the Panic of 1884

* Panic of 1893, a US recession with bank failures

* Australian banking crisis of 1893

* Panic of 1896

* Panic of 1901, a U.S. economic recession that started with a fight for financial control of the

Northern Pacific Railway

* Panic of 1907, a U.S. economic recession with bank failures

* Depression of 1920-21, a U.S. economic recession following the end of WW1

* Wall Street Crash of 1929 and Great Depression (1929–1939) the worst depression of modern

history

The Great London Exhibition (1851)

Lasting just 6

months, More than

14,000 exhibitors

from around the

world... 6,039,722

visitors—equivalent

to a third of the entire

population of Britain

at the time—visited

the Great Exhibition. The Great

Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations or The Great Exhibition (sometimes referred

to as the Crystal Palace Exhibition in reference to the temporary structure in which it was held),

an international exhibition, took place in Hyde Park, London, from 1 May to 15 October 1851.

It

was the first in a series of World’s Fairs, exhibitions of culture and industry that became

popular in the 19th century. The Great Exhibition was organized by Henry Cole and

by Prince Albert, husband of the reigning

monarch of the United Kingdom, Queen

Victoria. Famous people of the time attended,

including Charles Darwin, Karl Marx, Samuel

Colt, members of the Orléanist Royal Family

and the writers Charlotte Brontë, Charles

Dickens, Lewis Carroll, George Eliot, Alfred

Tennyson and William Makepeace Thackeray.

The Crystal Palace was an enormous success,

considered an architectural marvel, but also

an engineering triumph that showed the importance of the Exhibition itself. The building was

later moved and re-erected in 1854 in enlarged form at Sydenham Hill in south London, an area

that was renamed Crystal Palace. It was

destroyed by fire on 30 November 1936.

Visitors “could watch the entire process

of cotton production from spinning to

finished cloth. Scientific instruments

were found in class X, and included electric telegraphs, microscopes, air pumps

and barometers, as well as musical, horological and surgical instruments.”

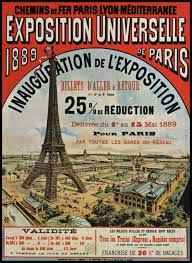

Paris Exposition Universelle of 1855 & 1889

The Exposition Universelle of 1855 was an International Exhibition held on the Champs-Élysées in Paris from 15 May to 15

November 1855. Lasted only 6 months, then destroyed. The exposition covered 16 hectares (40 acres) with 34 countries participating.

According to its official report, 5,162,330 visitors attended the

exposition. The arts displayed were shown in a separate pavilion

on Avenue Montaigne. There were works from artists from 29

countries. For the exposition, Napoleon III requested a classification system for France’s best Bordeaux wines which were to be on

display for visitors from around the world. Brokers from the wine

industry ranked the wines according to a château’s reputation and

trading price, which at that time was directly related to quality. The result was the important

Bordeaux Wine Official Classification of 1855.

The Exposition Universelle of 1889 was a world’s fair held in Paris,

France, from 6 May to 31 October 1889, lasting only 6 months. It was the

fourth of eight expositions held in the city

between 1855 and 1937. It attracted more

than thirty-two million visitors. The most

famous structure created for the Exposition, and still remaining, is the Eiffel

Tower. One important goal of the Exposition was to present the latest in science

and technology. Thomas Edison visited

the Exposition to visit a pavilion devoted to his recent inventions, including an improved phonograph with clearer sound

quality.

Another new technology that was promoted at the Exposition was the safety elevator,

developed by a new American company, Otis Elevator. Otis

built the elevators carrying passengers up the legs of the

Eiffel Tower to the first level. When journalists expressed

concern about the safety of the elevators, Otis technicians

filled one elevator with three

thousand kilograms of lead,

simulating passengers, and

then, with journalists from

around the world watching,

cut the cable with an axe.

The elevator’s fall was

halted ten feet above the ground by the Otis safety brakes. There

were pavilions especially devoted to the telephone and to electricity,

and others devoted to maritime navigation, and another, the Palais

de Guerre or Palace of War, to developments in military technology,

such as naval artillery.

1897 Brussels International Exposition

The Brussels International Exposition of 1897 was a World’s fair

held in Brussels, Belgium, from May 1897 through November 1897,

lasting just 7 months. There were 27 participating countries, and an

estimated attendance of 7.8 million people! A public favorite at the

World’s fair was Vieux-Bruxelles (also called Bruxelles-Kermesse), a

miniature city and theme park evoking Brussels around 1830. Somewhat foreshadowing Main Street at Disneyland, Vieux-Bruxelles offered

visitors nostalgic, smaller-size reproductions of historic buildings.

Melbourne International Exhibition (1880)

The Melbourne International Exhibition is the eighth World’s fair

officially recognized by the Bureau International des Expositions (BIE)

and the first official World’s Fair in the Southern Hemisphere. The

Melbourne International Exhibition was held from 1 October 1880 until 30 April 1881. It was the

second international exhibition to be held in Australia, the first being held the previous year in

Sydney. 1.459 million people visited the exhibition.

National Exposition of Brazil, Rio de

Janeiro (1908)

The national commemorative Exhibition of the

centenary of the opening of the Ports of Brazil, also

known as Brazilian National Exposition of 1908 or the

National Exposition of Brazil at Rio de Janeiro, marked

a hundred years since the opening of the Brazilian ports

and celebrated Brazil’s trade and development.[3] It

opened in Urca, Rio de Janeiro on 11 August, stayed open

for only 3 months and received over 1 million visitors.

Russian Industrial & Art Exhibition Novgorod, Russia (1896)

The All-Russia Industrial and Art exhibition 1896 in Nizhny Novgorod was held from May

28 (June 9 N.S.) till October 1 (13 N.S.), 1896. The 1896 exhibition was the largest pre-revolution

exhibition in the Russian Empire and was organized with money allotted by Nicholas II, Emperor

of Russia.The exhibition demonstrated the best achievements of the industrial development in

Russia that began in the latter part of the 19th century.

• an early radio receiver (thunderstorm register) designed by Alexander Stepanovich Popov;

• the first Russian automobile designed by Evgeniy Yakovlev and Pyotr Freze;

• the world’s first hyperboloid steel tower-shell (Shukhov

Tower) and the world’s first steel lattice hanging and

arch-like overhead covers-shells

The Many Many USA Expositions and

Exhibitions from 1838 -1930

And so the Story goes…

The first Exposition in the US was held in Cincinnati in 1838. It was actually a Fair of the Ohio

Mechanics Institute held in the nation’s first permanent exhibition hall. Other cities began holding

similar expos, and building similar Exposition Halls – some grander than others, but all were

based on the same principal – they needed to be large and impressive and able to be built quickly.

And then there were the international expositions, which generally began with London’s famous

Crystal Palace in 1851. It’s stated plan was “to illustrate British Industrial Development”. Since

other nations were invited to participate. they each hoped to outdo each other. This exposition

was so successful that other Expos followed in the major cities of Europe. This, of course led to

the establishment of “World Fairs”and then after the success of the Industrial Expositions in the

US, the State Fairs began as a way to let rural America participate.

1893 Chicago’s World Columbian Exposition

With State Fairs, there was no longer a need for the yearly Industrial Expositions. Meant to

celebrate the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s arrival to the New World, the 1893 Columbian

Exposition was better known for its grand vision into the future. Also called the Chicago World’s

Fair, its organizers tried to outdo the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1889. They managed to stun

the world with a 690-acre city-within-a-city that showcased 65,000 exhibits. Columbian Exposition

electricity transformed night skies across America and would soon shape the future.

More than 27 million people–approximately one in four Americans—visited the fair by its close

six months later on Monday, October 30. Chicago had just ‘risen from the ashes’ of the Great

Chicago Fire, which had destroyed much of the city in 1871. Almost all of the fair’s structures

were designed to be temporary; of the more than 200 buildings erected for the fair, the only two

which still stand in place are the Palace of Fine Arts and the World’s Congress Auxiliary Building.

These plans were abandoned in July 1894, when much of the fairgrounds was destroyed in a fire.

Visitors saw a multitude of spectacular new developments including dish washers and a giant

ferris wheel. But it was the new-fangled electricity and all the wondrous contraptions it ran that

captured their imaginations.

Like the Great Exhibit in England 1851, this fair had far reaching impact. . Its scale and grandeur far exceeded the other world’s fairs, and it became a symbol of the emerging American

Exceptionalism, much in the same way that the Great Exhibition became a symbol of the Victorian

era United Kingdom. Edison General Electric, which at the time was merging with the Thomson-Houston Electric Company to form General Electric, put in a US$1.72 million bid to power

the Fair and its planned 93,000 incandescent lamps with direct current.

Visitor could marvel at the wonders of modern technology and during the evenings the buildings were rigged with brilliant light displays courtesy of Nikola Tesla himself. Chicago’s 1893

World’s Columbian Exposition was particularly successful — and famous — thanks in part to a

staggering array of cultural and technological marvels which debuted there, including some of

the first demonstrations of electrical power, the world’s first Ferris Wheel, and the first servings

of the candied popcorn that would later be dubbed “Cracker Jacks.” Nearly all the halls and

pavilions at the fair were temporary.

The Ferris Wheel was a favorite amusement powered

by electricity. George Washington Gale Ferris carried more

than 1.5 million riders to the dizzying height of a 24-story

building where they could view three states at once. The

first giant Ferris wheel had steep highs and lows. The

Midway Plaisance was open for fun well into the night

thanks to AC electric lighting.

One of the fair’s favorite attractions was a 4,500-foot

moving sidewalk with benches for its passengers. It only

cost a nickel. The sidewalk was designed primarily to carry

passengers who arrived by steamboats. It was capable of

moving up to 6,000

people at a time, up to

six miles per hour.

The Midway was an area for amusement, where spectators could casually catch a ride in a hot air balloon, watch

a sideshow, or view the fair in all of its entirety in a new

invention called a Ferris wheel.

Women’s Public Art & Architecture

Sophia Hayden, one of the few women architects in nineteenth-century

America, graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and,

as her first project, designed the 80,000 square-foot, two-story building

called the Woman’s Building.

A young woman, Hayden evidently suffered some kind of breakdown by the end of the project and never again designed a building. In

charge of this all-woman project was a Board of Lady Managers chaired

by Bertha Potter Palmer, a wealthy and influential patron of the arts.

Placing women in charge of their own building was considered a rather

revolutionary idea at the time and was not enthusiastically supported

by some Fair authorities.

When the World’s Fair opened in

1893, equal rights for women was still

a futuristic dream. American women

couldn’t vote and were relegated to the

margins of public life. But the times

they were slowly changing. Prominent

women spoke at the Fair about a number

of issues, including women’s right icon

Susan B. Anthony, labor rights reformer

Florence Kelley, and abolitionist Julia

Ward Howe. When the Chicago World’s

Fair was funded through Congress,

money was specifically allocated to

make sure that women were represented. By authorizing and funding the Chicago fair’s Board

of Lady Managers [in 1893], Congress was in fact recognizing the increasingly organized and

influential role of women in American society. New technologies such as domestic plumbing,

canning, commercial ice production, and the sewing machine had freed middle-class women from

many household tasks, and more and more women were entering college and the professions.

Many, including upper-class and professional women, were also joining social reform groups,

and these women’s organizations had, in turn, organized to increase their visibility and influence.

Despite the presence of prominent women at the Fair, there were still some important slights.

The Fair’s single largest event, held on July 4, 1893, didn’t include a single woman speaker. In

response, five women from the National Woman Suffrage Association stormed the Independence

Day program and handed a copy of their Declaration of Rights for Women to the chairman of

the event. Women in the United States wouldn’t get the vote until nearly three decades later with

the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1920.

The Strange Presentations of Infant

Incubators at the World’s Fairs

Neo Preemie babies, struggling for their lives,

were transferred from hospitals to show off

the new incubators at many World Exhibitions. Some died due to infection from human

contact! They ran these “exhibits” until 1940.

And the store goes …

The babies in incubators were a common

sideshow in the late 19th and early 20th

centuries. Premature infants could be found

at world’s fairs and in permanent exhibitions

like the one at Luna Park. Although infant

incubators were invented in the year 1888 by

Drs. Alan M. Thomas and William Champion,

these devices were not immediately widely used. To increase awareness of the benefits these

units provided, infant incubators containing premature babies were displayed at the 1897, 1898,

1901, and 1904 World Fairs.

Pierre Budin, a French physician who wondered why more hospitals weren’t investing in

incubators. The 1896 World’s Fair was the first babies were displayed. There, Martin Couney,

a German man, saw a display of several premature babies Budin had acquired on loan from a

Berlin hospital (say what???). Couney immediately realized that the unusual exhibit would save

babies’ lives, and that the public would pay to see babies in incubators. The sight was so unusual

that people crowded into the display, paying money while the doctors gave new life to the six

infants. Couney ran the exhibits for decades, even enlisting his daughter Hildegard, the preemie

who survived, to help at an Atlantic City incubator exhibit. He took the babies at no charge and

received them from hospitals all over the country.

Newspapers advertised the incubators with

“lives are being preserved by this method.”

The exhibit required an entrance fee of twenty-five cents and visitors could also purchase

souvenirs and refreshments from the adjoining

shop and café. There were some setbacks with

the infant incubator display as the sanitary

conditions were not always consistent and some

babies died of illness! The incubator area was

then modified by installing glass walls to separate the babies from visitors, thus decreasing

the exposure of the infants. Now known as

“isolettes,” these units are a vital component to

caring for neonates in modern neonatal intensive care units.

The Incredible Light Shows of Electricity

with Edison & Tesla

or the Story goes…

It was the new-fangled electricity and all the

wondrous contraptions it ran that captured the imaginations of all who attended the exhibition. Since much

of the fair was run by AC power, visitors were able

to experience the profound changes electricity would

soon make in their daily lives. Outside the venues,

an elevated railroad carried 50,000 visitors per hour,

while within the venues, visitors were transported

by a loop-line elevated electric railcar, an electric boat

on a canal, and a moving sidewalk.

Famed Journalist, Murat Halstead wrote in Cosmopolitan: “The Fair, considered as an electrical exposition

only, would be well worthy of the attention of the world. Look from a distance at night, upon

the broad spaces it fills, and the majestic sweep of the

searching lights, and it is as if the earth and sky were

transformed by the immeasurable wands of colossal

magicians. The superb dome of the structure, that is

the central glory of the display, is glowing as if bound

by wreaths of stars. It is electricity! When the whole

casket is illuminated, the cornices of the palaces of the

White City are defined with celestial fire. The waters

that are at play leap and flash with it. There are borders

of lamps around the lagoon.

The Button That Turned On

The Columbian Exposition Electricity

On May 1 (May Day), 1893, throngs of people anxiously

waited for President Grover Cleveland to press the button

that was wired in Washington to electrify the fair. It was

similar to those used in most telegraph offices, but this

one was gold instead of steel. The dates 1492 – 1893 were

painted in silver on the bottom level of the three-tiered

pyramid sitting

on the ceremonial

table. Although

only the lightest touch was necessary, President Cleveland

brought his fist down with such force he nearly shattered

the button.

People swarmed to Chicago for a glimpse of the future.

The Chicago World’s Fair introduced a stunningly long

list of new products that remain on shelves to this day.

Among them were Juicy Fruit gum, Cracker Jacks, spray

paint and Shredded Wheat. Also included in the list

were products powered by electricity that would redefine American lives. Among them were Fax machines,

telephones, an electric railway, neon lights, bed warmers,

fans, radiators, and a cure-all electric belt. The Columbian

Exposition electricity building featured a fully electric

kitchen complete with a small range, hot plate, broiler,

kettle and saucepan.

The touch of that button set the great Allis engine at Machinery Hall in Chicago into motion. In

one profound moment, the Columbian Exposition electricity sparked the fair to life, ushering in

the electric age. The White City incorporated electricity into every aspect of the fair. It also meant

the fair would remain open at night. The Westinghouse space reserved a section in the building

for Nikola Tesla. His exhibit featured many of his early

AC devices. Among them were motors, armatures, and

generators, phosphorescent signs, fluorescent lamps and

neon lamps. He also displayed vacuum tubes illuminated by means of wireless transmission, his rotating

egg of Columbus and sheets of crackling light created

by high-frequency discharges between two insulated

plates. Of course, Tesla’s presence was felt in more

than just his display. His work in AC power systems

touched virtually every part of the fair. Westinghouse’s

successful implementation of AC across the fair was

publicized worldwide.

His 12,000-horsepower AC polyphase generators powered the fair effectively and safely.

Even skeptics like Lord Kelvin had to recognize the superiority of AC, which had been greatly

advanced by Tesla. In 1893 Westinghouse Electric designed a large AC system for Niagara Falls.

It was activated on August 26, 1895. Niagara Falls was the final victory of Tesla’s Polyphase

Alternating Current (AC) Electricity, which is today lighting the entire globe. On November 15th,

1896, the City of Buffalo joined the power grid

being generated from Niagara Falls, approximately

26 miles away. It became the first long distance

transmission of steady supplies of clean, carbonfree hydroelectricity for commercial purposes.

Not just Chicago, but nearly every other World

Fair were lit up with Free Energy.

The Electricity Building was one of the most

popular attractions at the fair. Electricity was still

a novelty for people in 1893. At night, the inside of the building was lit up much brighter than the other

buildings in the fair. There was music playing from

phonographs, motion picture viewing stations, and a

model house filled with electric appliances.

This exhibit was said to

display the technological

leap society would make

with the usage of the

electric power as much

of the world still relied

on alternative sources of

light such as daylight, candles, and gas or oil lighting. The massive

Electricity Building was 350 ft. in length and 767 ft. long or more

than 1 football field wide by 7 football fields in length! The 2nd story

was composed of a series of galleries connected across the nave by 8

bridges, with access by 8 grand staircases. The east and west central pavilions were composed

of two towers 168 ft. high. In front of these two was a great portico composed of the Corinthian

order with full columns. The central feature was a great semi-circular window, above which,

102 feet above the ground, was a colonnade forming an open loggia, or gallery, commanding a

spectacular view over the Lagoon and all the north portion of the grounds.

1901 Buffalo Pan American Exhibition

The Pan-American Exposition was a World’s Fair held

in Buffalo, New York, United States, from May 1 through

November 2, 1901. The fair occupied 350 acres (0.55 sq mi)

of land on the western edge of what is now Delaware Park,

extending from Delaware Avenue to Elmwood Avenue

and northward to Great Arrow Avenue. It is remembered

today primarily for being the location of the assassination of United States President William McKinley at the

Temple of Music on September 6, 1901. The exposition

was illuminated at night. Thomas A. Edison, Inc. filmed

it during the day and a pan of it at night. On the

day prior to the shooting, McKinley had given an

address at the exposition, which began as follows:

“ Expositions are the timekeepers of progress.

They record the world’s advancement. They stimulate the energy, enterprise, and intellect of the

people; and quicken human genius. They go into

the home. They broaden and brighten the daily

life of the people. They open mighty storehouses

of information to the student”. The newly developed X-ray machine was displayed at the fair, but

doctors were reluctant to use it on McKinley to

search for the bullet because they did not know

what side effects it might have had on him. Also,

the operating room at the exposition’s emergency

hospital did not have any electric lighting, even

though the exteriors of many of the buildings were

covered with thousands of light bulbs. Doctors

used a pan to reflect sunlight onto the operating

table as they treated McKinley’s wounds.

St. Louis World’s Fair 1904

The Louisiana Purchase Exposition, informally known as the

St. Louis World’s Fair, was an international exposition held in

St. Louis, Missouri, United States, from April 30 to December 1,

1904, a 7 month event. Local, state, and federal funds totaling $15

million were used to finance the event. More than 60 countries

and 45 American states-maintained exhibition spaces at the fair,

which was attended by nearly 19.7 million people!?! There were

over 1,500 buildings, connected by some 75 miles (121 km) of

roads and walkways. It was said to be impossible to give even

a hurried glance at everything in less than a week. The Palace

of Agriculture alone covered some 20 acres.

Wireless telephone – The “wireless telephony” unit or “radiophone” installed at the St. Louis World Fair was a thing of

wonder to the crowds. Music or spoken messages were transmitted from an apparatus within the Palace of Electricity to a

telephone receiver out in the courtyard. The receiver, which

was attached to nothing, when placed to the ear allowed a visitor to hear the transmission. This

radiophone, invented by Alexander Graham Bell, consisted of a transmitter which transformed

sound waves into light waves and a receiver which converted the light waves back into sound

waves. This technology has since developed into the radio and early mobile phones.

Early fax machine – The telautograph, the precursor to the modern-day fax machine, was

invented in 1888 by the American scientist, Elisha Gray who at one point in time contested Alexander Graham Bell’s invention of the telephone. The telautograph was a device which could send

electrical impulses to the receiving pen of the device, in order to be able to recreate drawings to

a piece of paper while a person simultaneously wrote them longhand on the other end of the

device. In 1900, Gray’s assistant, Foster Ritchie, improved upon the original design, and it was

this device that was displayed at the 1904 World’s Fair and marketed for the next thirty years.

Personal automobile - One of the most popular attractions of the Exposition was contained in

the Palace of Transportation: automobiles and motor cars.[14] The automobile display contained

140 models including ones powered by gasoline, steam, and electricity. The private automobile

first made its public debut at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. Four years after the Louisiana

Purchase Exposition, the Ford Motor Company began producing the Ford Model T making the personal

automobile more affordable.

Airplane – The 1904 World’s Fair hosted the first-ever “Airship Contest” since aerial navigation

was still in its infancy at this time. The Exposition offered a grand prize of $100,000 to the airship

or other flying machine with the best time through a course marked out by stationary air balloons

while travelling at least 15 miles per hour. Although none were able to earn the grand prize, the

contest did witness the first public dirigible flight in America as well as numerous other flights

made by various airships. This was the first major event in a history of aviation in St. Louis leading to

the city’s nickname, Flight City. The science of aerial navigation continued to develop and has been

mastered since the 1904 Exposition. Interestingly the Wright Brothers flew the very first model

airplane at Kitty hawk, North Carolina in December of 1903!

St. Louis mayor Rolla Wells, Frank D. Hershberg, Florence

Hayward, Fair president David R. Francis, Archbishop John J.

Glennon, and Vatican commissioner Signor Coquitti (l to r) at the

opening of the Vatican Exhibit at the 1904 World’s Fair.

Sioux City, Iowa

In the late 19th Century, a number of

cities on the Great Plains constructed

“crop palaces” (also known as “grain

palaces”) to promote themselves and

their products. As the idea succeeded,

it spread, including: a Corn Palace

in Sioux City, Iowa, that was active

from 1887–1891. The original Mitchell

Corn Palace (known as “The Corn

Belt Exposition”) was built in 1892

to showcase the rich soil of South

Dakota and encourage people to

settle in the area.

Mitchell. S.Dakota

In 1904–1905, the

city of Mitchell mounted a challenge

to the city of Pierre in an unsuccessful attempt to replace it

as the state capital of South Dakota. As part of this effort,

the Corn Palace was rebuilt in 1905. In 1921, the Corn Palace

was rebuilt once again, with a design by the architectural

firm Rapp and Rapp of Chicago. Russian-style onion domes

and Moorish minarets were added in 1937, giving the Palace the

distinctive appearance that it has today. (so they just decided

Moorish minarets and onion domes would look cool?). And

why such a massive post office needed.

The map published in 1888. Population of Sioux City as

35,000. Council Bluffs, Iowa Post Office 1888

Fun, Fun, Fun Were The Tartarians

The Tickler @ Lakesides

Over 300 major league amusement parks

were “built” across the USA from the 1860’s - the

1920’s, or 5 per state. Then they caught fire

or were torn down. Coney Island alone had

3 major amusement park re-creations where

to recreate, yet we have been told/sold that

the USA class of immigrants were dirt poor

and were put to work 6-7 hours per day. This

is all before the Industrial “Evolution” kicked

into high gear, so again, we are told, labor

using horse n’ buggy, erected the iron, steel

and concrete while plans for the design of

the parks still remain a mystery.

White City is the common name of dozens

of amusement parks in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. Inspired by the

White City and Midway Plaisance sections of the World’s Columbian Exhibition of 1893, the parks

started gaining in popularity in the last few years of the 19th century. After the 1901 Pan-American

Exposition inspired the first Luna Park in Coney Island, a frenzy in building amusement parks

(including those to be named White City, Luna Park, and Electric Park) ensued in the first two

decades of the 20th century. Before the end of the year 1900, White City amusement parks were

making their appearance in Philadelphia (1898 - it was also known as Chestnut Hill Park) and

Cleveland (1900). Soon, some long-established parks changed their names to White City upon

the addition of amusement rides and a midway (Seattle, for example).

As the American amusement park was

increasing in popularity in the first few years

of the 1900s, the success of the 1901 Pan-American Exposition (particularly its “Trip to the

Moon” ride, featuring “Luna Park”) led to the

first Luna Park in Coney Island in 1903... and

an explosion of nearly identical amusement

parks soon followed. There were roughly 250

amusements operating in the United States in

1899; the number almost tripled (700) by 1905;

and more than doubled again (to 1500) by

1919 - and these latter figures do not include

the amusement parks that were opened and permanently closed by then.

Like their Luna Park and Electric Park cousins, a typical White City park featured a shoot the chutes and lagoon, a roller coaster (usually a figure eight or a mountain railway), a midway, a

Ferris wheel, games, and a pavilion. Some White City parks featured miniature railroads. Many

cities had two (or all three) of the Electric Park/Luna Park/White City triumvirate in their

vicinity... with each trying to outdo the others with new attractions. The competition was fierce,

often driving the electric parks out of business due to increased cost due to equipment upgrades and upkeep and increasing insurance costs. More than a few succumbed to fire. Only one park

that was given the White City name continues to operate today: Denver’s White City, opened in

1908, is currently Lakeside Amusement Park.

Denmark’s Tivoli Gardens first opened in 1843, when showman Georg Carstensen persuaded

King Christian VIII to let him build a pleasure garden outside the walls of Copenhagen. Originally

constructed on around 20 acres of land, Carstensen’s creation featured a series of oriental-inspired

buildings, a lake fashioned from part of the old city moat, flower gardens and bandstands lit

by colored gas lamps. The park quickly became a Copenhagen institution, and won fame for its

“Tivoli Boys Guard,” a collection of uniformed adolescents who paraded around the premises

playing music for visitors. Tivoli later added an iconic pantomime theater in 1878, and by the

early 1900s it featured more traditional amusement park fare including a wooden roller coaster

called the Bjerkebanen, or “Mountain Coaster,” as well as bumper cars and carousels. Tivoli

Gardens was nearly burned to the ground by Nazi sympathizers during World War II, but the

park reopened after only a few weeks and remains in operation to this day.

Coney Island Amusement Parks

Opened in 1897 by entrepreneur

George C. Tilyou, Steeplechase

Park was the first of three major

amusement parks that put New

York’s Coney Island on the map. The

park took its name from its signature attraction, a 1,100-foot steel

track where patrons could race one

another on mechanical horses, but

it also included a Ferris Wheel, a

space-inspired ride called “Trip to

the Moon” and a miniature railroad.

While Tilyou intended Steeplechase

to be the family-friendly antidote to

Coney Island’s seamier side, some

rides still ventured into territory that was risqué by Victorian standards.

The Human Pool Table

The Helter Skelter

Attractions like the

“Whichaway” and the “Human Pool Table” tossed strangers against one another and gave couples

an excuse to canoodle, and the wildly popular Blowhole Theater allowed spectators to watch

as air vents blew up unsuspecting female guests’ skirts. As the ladies struggled to cover themselves, a clown would shock their male counterparts with a cattle prod. Fire destroyed much of

Tilyou’s park in 1907, but he responded by building a more elaborate Steeplechase that remained

in operation until the 1960s. Ever the showman, he even charged ten cents for visitors to view

the charred ruins of the original park.

The Teaser

elephants marching through the promenade

luna parks goat carriages

loop the loop

Coney Island’s Dreamland only operated for seven years between 1904 and 1911, but during

that time it established itself as one of the most ambitious amusement parks ever constructed.

The brainchild of a former senator named William H. Reynolds, the site included a labyrinth of

unusual rides and attractions lit by an astounding one million electric light bulbs.

Visitors to Dreamland could charter a

gondola through a recreation of the canals of

Venice, brave gusts of refrigerated air during

a train ride through the mountains of Switzerland or relax at a Japanese teahouse. They

could also watch a twice-daily disaster spectacle where scores of actors fought a fire at

a mock six-story tenement building, or pay

a visit to Lilliputia, a pint-sized European

village where some 300 little people lived full

time. Dreamland featured everything from

freak shows and wild animals to imported Somali warriors and Eskimos, but perhaps its most

unusual offering was an exhibit where visitors could observe premature babies being kept alive

using incubators, which were then still a new and untested technology. The infants proved a huge

hit, but they and many other attractions had to be evacuated in May 1911, when a fire—ironically

triggered at a ride called the Hell Gate—leveled the property and shut Dreamland down for good.

Founded in 1903 by theme park impresarios Fred Thompson and Skip Dundy, Coney Island’s

Luna Park consisted of a gaudy cluster of domed buildings and towers illuminated by an eye-popping 250,000 light bulbs. The park specialized in high concept rides that transported visitors

to everywhere from 20,000 leagues under the sea to the North Pole and even the surface of the

moon. A trip to Luna could also serve as a stand in for world travel.

After a ride on an elephant, patrons could stroll a simulated “Streets of Delhi” populated by

dancing girls and costumed performers—many of them actually shipped in from India—or take

a tour through mock versions of Italy, Japan and Ireland. If they grew tired of walking, visitors

could relax in grandstands and watch the “War of the Worlds,” a miniature, pyrotechnic-heavy

sea battle in which the American Navy decimated an invading European armada. The park’s

owners also cashed in on the popularity of disaster rides by staging recreations of the destruction

of Pompeii and the Galveston flood of 1900. The carnage reenacted in these attractions became

all too real in 1944, when Luna fell victim to a three-alarm fire that began in one of its bathrooms.

The original site closed for good a few years after the blaze, but the iconic name “Luna Park” is

still used by dozens of amusement parks around the globe.

First opened in 1893, Saltair was a desert oasis situated on the south shore of Utah’s Great Salt Lake.

The Mormon Church originally commissioned the site in the hope of creating a wholesome “Coney

Island of the West” without the perceived sleaziness of the New York original. Their family-friendly

park proved an instant hit, as scores of visitors arrived by train from nearby Salt Lake City to enjoy

music, dancing and bathing in the lake’s saline-rich waters. Saltair’s most striking attraction was

its gargantuan pavilion, a four-story wonder adorned with domes and minarets that sat above the

lake on more than 2,000 wood pilings. Along with touring this “Pleasure Palace on Stilts,” visitors

could also show off their moves on a sprawling dance floor, ride roller coasters and carousels, and

watch fireworks displays and hot air balloon shows. The park boasted nearly half a million visitors

a year until 1925, when the iconic centerpiece burned in a fire. A rebuilt Saltair opened soon after,

but it failed to capture the magic—or the revenues—of the original. The park closed its doors for

good in 1958, and its abandoned pavilion was later destroyed in a second fire in 1970.

Pacific Northwest Amusement Parks

Council Crest Park 1907 set on

a Mountain top 1200’ high

Portland Oregon

Spokane’s Natatorium Park opened in 1889

Luna Park in West Seattle

operated from 1907 to 1913

The Oaks aka the Coney

Island

of the Northwest,

opened 1905

The original “Luna Park” on Coney Island was a massive spectacle of rides, ornate towers

and buildings covered in 250,000 electric lights. The park opened in 1903, and was destroyed 41

years later in 1944 by a massive fire that destroyed much of the park.

Above, Brazil (1908) and Kansas City exhibitions (1907) were lit up at nighttime. Walt Disney

cited the second Kansas City Electric Park as his primary inspiration for the design of the first

modern theme park, Disneyland.

Construction and Destruction of

the Chicago World’s Fair 1893

The story goes that these World Fairs and Exhibitions were only meant to be temporary and

construction was mainly paper Mache and facings to create artificial constructs. This is clearly

debunked showing these pictures from the construction phase

of the Chicago World Fair, which ran less than a year, then

torched. Though they used Tartarian structures, they were

modified and added to the existing structure. Look at the men

atop the steel dome structures…amazing!

next

The Western Capitol of Tartary;

San Francisco

1 comment:

Thank you for this series.

Morgan at CGI

Post a Comment