The One World Tartarians

The Greatest Civilization

Ever to Be Erased From History

James W. Lee

Chapter 18

The Western Capitol of

Tartary;

San Francisco

The first Cliff House was built in

1858, above Ocean Beach, in west

San Francisco. It has been rebuilt

five times since for various reasons, such

as remodeling or damage.

In 1894, the third, and most photographed, incarnation of the house was built

by Adolph Sutro, a successful mining engineer. Sutro built the seven-story mansion

in Victorian style, an elaborately decorated

structure dubbed the “Gingerbread House.”

Cliff House was the scene of a number

of historic events, including several shipwrecks. A wreck in 1887 caused damage to

the second Cliff House when the dynamite on the ship exploded. The first ship-to-shore transmission, using Morse Code, was received here in 1899 and in 1905; the first radio voice transmission

was sent from the house to a point a mile and a half away.

Cliff House survived the earthquake that struck San Francisco in 1906 with only minor damage.

It burned to the ground the following year, however. Sutro’s daughter began the construction of

a new Cliff House restaurant in 1908, but on a vastly smaller scale.

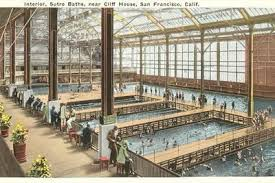

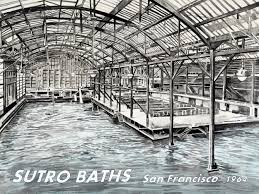

San Francisco Sutro Bath Houses

Once the largest indoor swimming establishment in the world.

Built in 1896 by former mayor and eccentric mining tycoon Adolph Sutro, the Sutro Baths were

a wonder of their time. The biggest indoor natatorium of its kind, the Baths used sea water from

adjacent Ocean Beach to fill six saltwater pools, and featured one freshwater pool, hundreds

of dressing rooms, slides, springboards, a large amphitheater, and later an ice rink. Sutro died

while the Baths were successful, and the attraction continued in popularity until it fell into disuse

during the hard economic times of the 1920s and 30s. Planned development along the oceanfront

property and multiple fires meant the Baths’ demise in 1966. The Baths remain a centerpiece of

the west side of the city’s history and its ruins are still explored by locals and tourists alike today.

The Sutro Baths opened in 1890, and was intended for the working people of San Francisco, who could

take his train out to the ocean sand dunes and play in the pools, enjoying the day swimming,

exploring his museum and eating in the restaurants. There were musical performances and dance

competitions, and other amusements provided for his guests, who could make a whole day of it

at the Baths. Covering three acres, six tide-fed seawater pools of varying sizes and temperatures

were housed under enormous glass arches. The construction required 10,000 barrels of cement,

1.7 million gallons of sea water, and $1 million 1896 dollars. A promenade overlooking the pools

featured a museum of curiosities collected by Sutro on his travels, including exotic plants, taxidermy, geologic specimens, and Egyptian mummies. Guests could avail themselves of 500 tiny

dressing rooms and observation bleachers with seating for 3700 spectators.

Sutro kept the fees low so most city residents could afford to come: 5 cents for the train and

25 cents to swim (including a swimsuit and towel to use). Up to 25,000 bathers could fit into the

Baths on a given day, and more than 1600 could be accommodated in the 517 private dressing

rooms (conveniently, there were 40,000 towels available for rent). The entire establishment was

constructed inside an enormous three-peaked glass enclosure. According to visitors’ reports, a

great deal of the structure was made from stained glass, and the baths below were frequently

dappled with rainbow colors from the sun shining down through the roof. Sutro placed dozens of

display cases full of his memorabilia from trips around the world--including, weirdly enough, a

mummy--all throughout the halls to make his attraction educational too. The place almost sounds

like a direct ancestor of the sumptuous discos and raves for which San Francisco is still famous.

Next to the Cliff House at Great Highway and Point Lobos. The baths, built by legendary local

weirdo Adolph Sutro must have been a sight to behold: six huge indoor pools filled with ocean water, surrounded by seats for 7,000 spectators. The baths were replete with statuary and plant

conservatories featuring palms and real Egyptian relics, like something out of Norma Desmond’s

wettest dream. The baths also housed several restaurants, a museum, trapezes, and water-slides.

But like so many of San Francisco’s magnificently weird landmarks --- Fleishacker Pool, Playland

at the Beach, the Fox Theater--the Sutro Baths were too good to last. On June 26th, 1966, just as a

wrecking ball was poised to begin smashing in the walls of the legendary Baths (and two weeks

before the bankruptcy that would have ruined the owners) a mysterious fire broke out and burned

the whole place to the ground. It turned out that the building was heavily insured; the owners

collected their massive settlement and quickly left town, leaving many suspicions but no tangible

evidence of fraud and arson. The ruins of the baths still linger as one of the most mysterious sites

of San Francisco. The Ferries and Cliff Steam Line, opened on March 1, 1886, ran from California

and Central (now Presidio Ave.) to a point above the Cliff House at 48th and Point Lobos.

1894 California Midwinter International

Exposition

San Francisco’s First World’s

Fair…Dedicated to the Wonders of California.

Very little remains of the extraordinary Midwinter

Exposition installation of 1894. The brainchild of the

San Francisco Chronicle’s publisher Michael de Young,

who had been inspired and delighted by the White City

of Chicago’s 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, San

Francisco’s first World’s Fair was executed from dream

to reality in less than six months.

The center of the fair was in the area now known

as the Music Concourse, then nearly unrecognizable

except for the general contours.

At its center, an Eiffel-Tower-inspired Electric Tower

rose 266 feet, offering intrepid climbers a bird’s eye

view of the fair and the early park. The fair buildings

represented various exotic cultural and architectural

influences, from minarets and Indian fantasies to

Spanish mission style. Tree-loving park superintendent

John McLaren was reportedly

none too thrilled about the

hijacking of his new parkland

for commercial venture, but

he begrudgingly relented.

The fair opened on January 27, 1894 on 160 acres at the park’s center,

dubbed The Sunset City. 180 buildings had been constructed in record

time to showcase all of California’s counties as well as selected foreign

countries and other states.

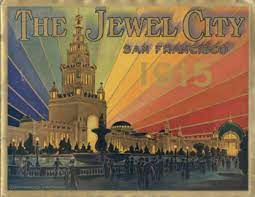

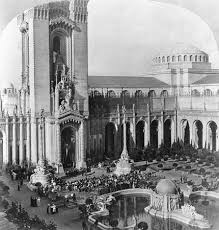

The Pan Pacific Exhibition in San Francisco,

California in 1915~

Open for 9 months

..Then Destroyed Directly Thereafter

Just nine years after the devastating 1906 earthquake, San Francisco staged the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition, celebrating the opening of the Panama Canal in August, 1914 and

showing more than 18 million visitors from around the world that it remained “the city that knew

how.” Understandably, the universal reaction of fairgoers was “a sense of wonder.” Amazingly,

there were no bridges across the San Francisco Bay and the population of San Francisco, still

reeling from the major 1906 Earthquake, was estimated to be under 200,000 people!

The building of the canal itself was, of course, an incredible feat: Over 50 years in the making,

it was dubbed “The 13th Labor of Hercules.” And so was the creation of the Exposition, beginning

with the placement of 300,000 cubic yards of fill to create land for the site from what had formerly

been San Francisco Bay and is now San Francisco’s Marina district.

The times were heady, and rapid strides were being made in engineering and manufacturing.

Consider just a few notable aspects:

The fair featured a reproduction of the Panama Canal that covered five acres. Visitors rode

around the model on a moving platform, listening to information over a telephone receiver.

The first transcontinental telephone call was made by Alexander Graham Bell to the fairgrounds before the fair opened, and a cross-country call was made every day the fair was open.

The ukulele (originally a Portuguese instrument, but adopted by the Hawaiians) was first played

in the United States at the 1915 fair, creating a ukulele craze in the 1920s.

An actual Ford assembly line was set up in the Palace of Transportation and turned out one

car every 10 minutes for three hours every afternoon, except Sunday. 4,400 cars were produced

during the Exposition.

The entire area was illuminated by indirect lighting by General Electric. The “Scintillator,” a

battery of searchlights on a barge in the Bay, beamed 48 lights in seven colors across San Francisco’s fog banks. If the fog wasn’t in -- no problem: A steam locomotive was available to generate

artificial fog.

Personalities abounded: Thomas Edison and Henry Ford were honored at a luncheon; Edison

had perfected a storage battery that was exhibited at the fair. A pre-teen Ansel Adams was a

frequent visitor.

• The Liberty Bell made a cross-country pilgrimage from Philadelphia to be displayed at the

fair. Notables, such as Thomas Edison, were often photographed with the bell.

• The Machinery Palace was the largest wooden and steel building in the world at the time;

the entire personnel of the U.S. Army and Navy could have fit inside. The first-ever indoor

flight occurred when Lincoln Beachey flew through the building before it was completed.

George W. Kelham was chosen as chief of architecture. Working with the architectural council, he

developed an elegantly simple plan. It grouped the

eight main exhibition palaces together in a single

block. This main block was then flanked on the eastern

end by the Palace of Machinery and on the western

end by a neo-classic fantasy monument, Bernard

Maybeck’s Palace of Fine Arts.

This grouping was crowned by an Italianate main

tower known as the Tower of Jewels, which was

adorned with 102,000 glass gems (Novagems, in the

parlance of the period) that sparkled when swayed

by the wind (Jeweled watch fobs, rings, pins and other objects were popular souvenirs). The

block also included several magnificent courts: The Court of the Universe, the Court of Abundance,

and the Court of the Four Seasons. While the buildings appeared substantial, they were intended to

last only for a year, after which they would be demolished. The Palace of Fine Arts underwent

a major restoration in the 1960s.

Lincoln Beachey climbing into his monoplane on March 14, 1915 at the Panama-Pacific International Exhibition just before taking off for the last time.

The monumental exhibition palaces formed a core that

held together two outer and very different zones of the Exposition. At the western end beyond the Palace of Fine arts were

exhibition halls built by participating countries and states.

At the eastern end was a sixty-five acre amusement park

and concession district called The Zone. All together, the Fair

occupied 635 acres..approximately 76 city blocks. The total

construction cost was about $15,000,000, and the project

consumed over 100 million board feet of lumber. Please

Remember, this was just nine years after the Great San Francisco Earthquake of 1906. The Palace of Machinery, styled

after the Roman Baths of Caracalla, was the largest wood and

steel building in the world at that time. It measured nearly

a thousand feet in length, 367 feet in width and was 136 feet

high. More than 2,000 exhibits were displayed

inside on two miles of aisles. The soldiers and

sailors of Uncle Sam’s 1915 Army and Navy could

have fit into the Machinery Palace with room to

spare. Aviator Lincoln Beachey flew through the

building before it was completed in the first-ever

indoor flight. His speed through the building

-- a blazing 40 miles per hour.

The Column of Progress commanded the entire north front of the Exposition. Symmes Richardson, the architect drew his inspiration from Trajan’s Column in Rome. It completed the

symbolism of the Exposition’s sculpture and architecture, as the joyous Fountain of Energy at

the other end of the north-south axis began it.

The Palace of Horticulture designed by Bakewell and Brown is the largest and most splendid

of the garden structures. Byzantine in its architecture it suggested the Mosque of Ahmed I at

Constantinople. This was the palace of the bounty of nature; its adornment symbolized the rich

yield of California fields. The Palace of Education combined Spanish Renaissance and Moorish

designs. In the Tympanum above the central portal, sculptor Gustav Gerlach created the group

“Education.” In the center, the teacher sits with her pupils under the Tree of Knowledge; on the

left, the mother instructs her children; on the right the young man, his school days past, works

out a problem in science. Thus, the group depicts the various stages of education.

The California Building designed by Thomas H. Burditt was by far the largest state building

ever erected at the time. From its façade, Fray Junipero Serra looks over a charming garden which

represents the private of Santa Barbara Mission, but this Mission style building was grander

than those built by the padres of California. It covered five acres! Inside walls were hung with

tapestries loaned by Mrs. Phoebe A. Hearst. Displays from the fifty-eight California counties

were presented.

Color was a major unifying element in the design of the Exposition. Jules Guerin a colorist,

painter, and designer oversaw the Exposition’s color schemes. He created a specially blended

gypsum and hemp plaster material in hues of old ivory that mimicked the travertine marble

used in ancient Rome. This plaster was applied over most of the buildings, statues, and walls.

Eight accent colors were used throughout the Exposition:

• French green for garden lattices

• Deep cerulean blue in recessed panels and ceiling vaults

• Pink-orange for flagpoles

• Pinkish-red flecked with brown for the background of

colonnades

• Golden-burnt-orange for moldings and small domes

• Terra cotta for other domes

• Gold for statuary

• Antique green for urns and vases.

Very romantic and ornate sculptures were typical of the era and profusely adorned the Fair

and its structures. Karl Bitter, Director of the Department of Sculpture, and A. Stirling Calder,

the Exposition’s acting chief of sculpture, commissioned more than fifteen hundred sculpture

from artists around the world. These stood on columns, in niches, in fountains, and as freestanding groups throughout the Expositions. In the South Garden was the Calder Fountain

of Energy. Resting in the center of the pool and supported by a circle of figures representing

the dance of the oceans, is the Earth, surmounted by a figure of Energy, the force that dug the

canal with Fame and Victory blowing bugles from their shoulders.

Bernard Maybeck, the designer of the Palace of Fine Arts, believed that architecture here in

California, to be beautiful, needed only to be an effective background for landscape. He was able

to achieve this end in his design. The sweeping arc of the building on the shore of the lagoon

254 The One World Tartarians

is a mere backdrop for the trees and plants. The central rotunda ‘s entablature contains Bruno

Louis Zimm’s three panels representing “The Struggle for the Beautiful.” On an altar before the

rotunda knelt Robert Stackpole’s figure of Venus, representing the Beautiful to whom all art is

servant. Robert Louis Zimm created the panel in front of the altar on pictured Genius, the source

of inspiration. Above, in the dome, Robert Reid’s eight murals symbolize the conception and

birth of art, its commitment to the earth, and its progress and acceptance by the human intellect.

A three-acre Japanese garden was created at the south entrance to the Fine Arts Palace. This

garden was comprised of rocks up to three tons in weight, 25,000 square feet of turf, 1300 trees, 4400 small

plants, and tons of small stones and gravel brought from Japan. The Golden Pavilion, a copy of

a Japanese temple, and two graceful teahouses were located within this Japanese garden, which

was staffed largely by the government of Japan.

As Ben Macomber in his book The Jewel City states, “No other of the palaces would wear so

well in its beauty if it were set up for the joy of future generations. It would be a glorious thing

for San Francisco if the Fine Arts Palace could be made permanent in Golden Gate Park.” As we

know his words were heeded and the Palace of Fine Arts still stands in all of its beauty, albeit in

its original site, rather than in Golden Gate Park.

The Palace of Fine Arts contained what the International Jury declared to be the best and most

important collection of modern art that had been yet assembled in America. The war in Europe

did prevent some countries like Russia and Germany from sending art works, it led other countries such as France and Italy to send more than they might otherwise have sent.

Ernest Coxhead, the San Francisco architect who designed the home of Dr. Thomas Williams

that now houses the Museum of American Heritage, was instrumental in developing the detailed

plans for the 1915 Exposition. His plans were presented to the US Congress in 1911 during the

competition between San Francisco and New Orleans as to which city would have the privilege

of hosting the celebration of the opening of the Panama Canal.

Lighting At The Fair

Lighting at the fair was the crowning achievement. W.D’Arcy, who was called “the Aladdin of

the 1915 City Luminous,” was loaned to the Exposition by a young General Electric company

eager to promote the miracles of its technology. Never before had an attempt been made to light

an exposition as this one was lighted.

The massive exhibition area was illuminated at night by indirect lighting of the softest, warmest,

and mellowest of colors, all seemingly without source. The radiance of the 43 story Tower of

Jewels came from huge searchlights aimed at it from a circle of hidden stations. Perhaps the most

exquisite and dazzling feature of the fair, the Tower, with its 102,000 pieces of glittering multicolored

cut Bohemian glass, refracted and reflected both sunlight and nighttime illumination.

The many-colored fan of enormous rays, the Scintillator, which stood against the sky behind

the Exposition, was produced by a searchlight battery of thirty-six great projectors mounted

on the breakwaters of the Yacht Harbor. It was manned nightly by a company of marines, who

manipulated the fan of lights in precise drills at night.

Around the walls of the palaces stood tall Venetian masts, topped with shields or banners.

Concealed behind the heraldic emblems were powerful magnesite arc lamps. Other concealed lights

gleamed through the waters of the fountains. In the Court of the Universe they were white, in the

Court of the Seasons green, and in the Court of the Ages they were red. The palaces themselves

Chapter 18: The Western Capitol of Tartary; San Francisco 255

were not externally illuminated at night, though they appeared to be lighted internally. Behind

each window and doorway were hung strings of lights backed by reflectors.

The illumination was at its best on a misty night when the moisture in the air provided a screen

to catch the colored lights and create the effect of an aurora overhead. If natural fog wasn’t present

to supply this background for the great beams of the Scintillator, clouds of steam from a steam

locomotive positioned on the breakwater provided the missing mist.

Sculptures at the Fair

Sculpture was an integral part of the Panama-Pacific International

Exposition. A Stirling Calder was the acting chief of sculpture, and

under his direction was a large staff of skilled workmen, hired to

turn out thousands of sculptures and decorations. These works were

made of plaster and tinted to match or compliment the buildings.

“The End of the Trail” by James Earle Fraser was one of the most

popular and poignant works of art at the fair. It showed an Indian

astride his exhausted horse, representing the Native American’s

failed battle against encroaching civilization.

Many other notable sculptures were also created:

• Robert Aikens depicted man’s progress from birth to death

in the “Fountain of the Earth.

• A.A. Weinmann’s statues “The Rising Sun” and “The Setting

Sun” were placed in the” Court of the Universe.

• Daniel Chester French’s statue depicted an angelic figure

with its creation of man and woman below.

• C.L Pietro created one of the strongest sculptures in “The Mother and the Dead,” protesting

the ‘great war’ which was leaving Europe with only the aged and the children.

• A.Stirling Calder had several sculptures. In front of The Tower of Jewels stands his joyous

“Fountain of Energy” a depiction of the union of the Atlantic and Pacific by the Panama

Canal. He also created the “Star Maidens” that adorned the Tower of Jewels.

• The sculpture “Nations of the West” was located in the Courtyard of the Universe, atop the

Arch of the Setting Sun. This sculpture, the joint work of A. Sterling Calder, Leo Lentelli,

and F. G. R. Roth was comprised of figures representing an American Indian, pioneers

gathered around the Prairie Schooner, and the figures of Mother of Tomorrow and Spirit

of Enterprise.

Industrial Displays

The Exposition emphasized contemporary events and technology from the previous decade.

The moving-picture machine was extensively used to illustrate industrial progress in various

exhibits, and the presence of both mechanical and electrical devices was larger than life in many

cases. Exhibits in the Palace of Machinery showcased Diesel engines, water-driven power plants

and numerous electrical motors and communication devices. On opening day, President Woodrow

Wilson started, by wireless, the Diesel-driven generator that supplied all of the direct current

used in the Palace.

The Underwood Exhibit in the Palace of Liberal Arts featured a $10,000 typewriter, “an exact

reproduction of the machine you will eventually buy.” It was 1728 times larger than the standard Underwood typewriter and weighed 14 tons. News stories were typed on it daily. But the

greatest amount of space was given to labor saving devices, safety inventions and machines that

increased the comfort (if not the comfort level) of humanity. The overwhelming theme was that

machines would play a major role in making life more comfortable and enjoyable.

Agriculture

Today we consider agriculture an industry, but the typical fair-goer of 1915 considered the

growing of ornamental plants and foodstuffs two separate endeavors, neither of them “industrial”. The Fair reflected this outlook, incorporating three display halls related to the growing and

production of agricultural products: The Palace of Horticulture, the Forestry building, and the

Palace of Agriculture. The Palace of Agriculture had a distinct “State Fair” flavor, with displays

of farm products and awards for products of high quality. This Palace was prominently located

at the northwest corner of the Court of the Universe. The award certificate shown here (Courtesy

Campbell Historical Museums) was awarded to the Orchard City Canning Company of Campbell, CA for its Assorted Canned Fruits.

The Palace of Horticulture displayed beautiful flowers and ornamental plants and was located

adjacent to the Palace of Forestry near the Baker Street entrance to the Fairgrounds. As might be

expected, the Forestry building was concerned with the growing of trees and the production of

lumber.

The Entertainments

No fair is complete without its sideshow, and the fair’s eastern section, known as “The Zone”,

occupied a space the equivalent of seven city blocks in area and contained a variety of entertainments, rides, commercial stands, souvenir shops, and other typical fair staples. However, some

of the things to be found in the zone were very untypical, including the “Aeroscope”, a ride that

consisted of a small two-story structure mounted on the end of a 285-foot swing-arm. It was

designed and built by Joseph Strauss, the designer and builder of the Golden Gate Bridge. Riders

were treated to an aerial view of the fair and nearby San Francisco. It was especially spectacular

at night. Another popular ride circled a five-acre operating model of the Panama Canal. For their

50-cent admission, passengers occupying one of the hundred chairs circling the model on elevated

tracks could learn about the canal through earphones during their half-hour ride. The soundtrack

came from a phonograph. Fairgoers could also observe babies (real) in incubators, experience a

rowdy 49’ers prospecting camp (not spring training), and a submarine ride. They could choose

to be entertained, awed, scared, impressed and fed at a seemingly innumerable number of rides,

restaurants and concessions.

Other entertainments might be experienced throughout the fair area, including air shows,

concerts, demonstrations of arts, crafts and and national culture. The air shows were quite popular,

drawing crowds of 10,000 or more spectators, although daredevil pilot Lincoln Beachy was killed

during one of the air exhibitions when his plane experienced a structural failure and crashed.

After The Lights Went Out

The final midnight arrived, the last music, “Taps”, was played

from the Tower of Jewels, the last fairgoer departed, and the lights

of the 1915 World’s Fair went out forever. The Tower of Jewels, built

at a cost of $413,000, was sold to a demolition firm for $9,000.

Individual jewels were sold to souvenir hunters for a dollar each.

Some prominent statues, including “Nations of the East” and “Nations

of the West”, were not salvageable and were destroyed along with

the arches on which they were mounted. By 1917, the work was

done, with structures demolished and the land (or the landfill, at least) was

restored. Over $900,000 was realized from the salvage effort. Between

February 20, 1915 (opening day) and December 4, the closing day,

over 18 million people passed through the entrance gates of the 1915

Panama-Pacific International Exposition. The Fair generated the

funds to construct San Francisco’s Civic Auditorium, and an additional $1,000,000 surplus, as well.

So the question has to be asked once again..how did 18 million people attend the exhibition?

Where did they lodge, how did they transport, how were they notified of the fair?

The San Diego 1915 Panama–California Exposition was held between January 1, 1915, and

January 1, 1917, the same exact year as the Great San Francisco Exhibition!

The exposition celebrated the opening of the Panama Canal

and was meant to tout San Diego as the first U.S. port of call for

ships traveling north after passing westward through the canal.

The fair was held in San Diego’s large urban Balboa Park. The

exposition’s location was selected to be inside the 1,400 acres

(570 ha) of Balboa Park. The East Gateway was approached by

drive and San Diego Electric Railway trolley cars winding up from

the city through the southern portion of the park. From the west,

the Cabrillo Bridge’s entrance was marked

with blooming giant century plants and

led straight to the dramatic West Gate (or

City Gate), with the city’s coat-of-arms

at its crown. The archway was flanked

by engaged Doric orders supporting an

entablature, with figures symbolizing the

Atlantic and Pacific oceans joining waters together, in commemoration of the

opening of the Panama Canal. These figures were the work of Furio Piccirilli.

While the west gateway was part of the Fine Arts Building, the east gateway

was designed to be the formal entrance for the California State Building. The

East or State Gateway carried the California state coat-of-arms over the arch. The spandrels over

the arch were filled with glazed colored tile commemorating the 1769 arrival of Spain and the

1846 State Constitutional Convention at Monterey. Near a large parking lot, the North gate led to

the ‘Painted Desert’ and 2,500-foot (760 m) long Isthmus street. The Santa Fe Railway-sponsored

‘Painted Desert’ (called “Indian Village” by guests), a 5-acre (2.0 ha), 300-person exhibit populated

by seven Native American tribes including the Apache, Navajo, and Tewa.

‘Painted Desert’,

which design and construction was supervised by the Southwestern archeologist Jesse L. Nusbaum,

had the appearance

of a rock structure

but was actually wire

frames covered in

cement. The Isthmus

was surrounded by

concessions, amusement rides and games,

a replica gem mine,

an ostrich farm, and a

250-foot (76 m) replica

of the Panama Canal.

One of the concessions

along the isthmus was

a “China Town”.

Santa Cruz, California The Boardwalk

In 1791, Father Fermin de Lasuen established a mission at Santa Cruz, the twelfth

mission to be founded in California. California became a state in 1850 and Santa

Cruz County was created as one of the

twenty-seven original counties.

By the turn

of the century logging, lime processing,

agriculture, and commercial fishing industries prospered in the area. Due to its mild

climate and scenic beauty Santa Cruz also

became a prominent resort community.

Since 1907. The boardwalk is oldest amusement park in California and one of the last seaside amusement parks on the west coast of the

United States.

Chapter 19

Children 4 Sale…

All Aboard the Foundling Trains

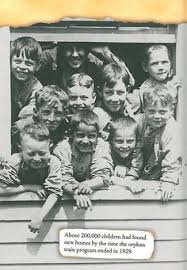

The first orphan trains operated prior to the Civil War. Over

250,000 children were transported from New York to the Midwest

over a 76-year period (1853-1929) in the largest mass migration of

children in American history. As many as one in four were Irish. Some

abolitionists feared that the orphan trains were being used as an extension

of slavery, and there was reason behind their fear. Not all the orphans

were being adopted. Many became slaves to farmers, child abusers and

indentured servants with no rights or freedoms. The first Orphan Trains

left Grand Central Station in late 1853 for Dowagiac, Michigan. The trains

continued to run for 75 years. The last official train ran to Texas in 1929.

Many children were sexually abused, mistreated, malnourished, and overworked in the Midwest

farms. Trains would stop in midwestern and southern towns, and the children would file off

and parade before the assembled townspeople, often on hastily constructed stages. Locals would

inspect the children, feel their muscles, look at their teeth, and question them. Contact between

the children and their families back east was strongly discouraged. Many of these children ran

away from the abusive new homes they were placed in.

These abandoned children were left to their own devices to obtain shelter and food, often

stealing, begging, selling matches and/or papers to support themselves. These children were

labeled as “Street Arabs”, “the dangerous classes”, and ‘street urchins” to name a few. In the mid

1800’s and early 1900’s of the United States history, these problems escalated and led Charles

Loring Brace, a minister in New York, to found The Children’s Aid Society in 1853 in New York

City. A report in the New York Times dated May 10, 1860, cited the four distinct classes of needy

they served: “First – Friendless and deserving young women. Second – Destitute children between the

ages of 3 and 14 years. Third – Motherless and orphan infants. Fourth. – Dependent mothers with children

who should not be separated.”

In the 1870s, the Catholic Church became concerned that many Catholic children were being

sent to Protestant homes and were being inculcated with Protestant values. They began operating

their own Placing Out program via the railroad sponsored by the New York Foundling Hospital.

Priests in towns along the railroad routes were notified that the Foundling Hospital had children

in need of homes. The priest would make an announcement at Sunday Mass and adults could

sign up for a child, specifying gender and preferred hair and eye color. It was common to have

children separated from their siblings, to not have birth certificates, and no further contact with their

parents or siblings. In many cases the only legal document for the children would have been

their baptismal certificate. By the age of 18, the children were released from their indenture and

were expected to make their own way in life.

Foster Care Was Created to Harvest Children.

In the United States, foster care started as a result of the efforts of Charles Loring Brace. “In

the mid-19th Century, some 30,000 homeless or neglected children lived in the New York City

streets and slums. “Brace took these children off the streets and placed them with families in most

states in the country. Brace believed the children would do best with a Christian farm family. He

did this to save them from “a lifetime of suffering” He sent these children to families by train,

which gave the name The Orphan Train Movement. “This lasted from 1853 to the early 1890s

1929? and transported more than 120,000 250,000? children to new lives.

“When Brace died in 1890, his sons took over his work of the Children’s Aid Society until

they retired. The Children’s Aid Society created “a foster care approach that became the basis

for the federal Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997” called Concurrent Planning. This greatly

impacted the foster care system.

Origins of US Foundling Homes

In the late 1860s, there was an epidemic of infanticide and child abandonment In New York City.

The Sisters of St. Peter’s Convent downtown on

Barclay Street regularly found abandoned babies

on their doorstep. Sister Mary Irene Fitzgibbon of

St. Peter’s approached Mother Mary Jerome, the

Superior of the Sisters of Charity, regarding the

need of rescuing these children. Archbishop (later

Cardinal) John McCloskey urged the Sisters to open an asylum for such children.

On October 11, 1869, three Sisters of Charity – Sisters Irene, Sister Teresa Vincent, and Ann

Aloysia – opened The New York Foundling Asylum of the Sisters of Charity. They received one

infant on their first night of operation. Forty-five more babies followed in that first month. To meet

overwhelming demand, Foundling opened a boarding department in November and began placing

children under the care of neighbors. Seventy-seven more babies followed in the next two months.

After two years, The Foundling had accepted 2,500 babies. The New-York Historical Society

has a collection of the notes left with the abandoned babies, which is part of a larger collection

of historic photographs of the Foundling maintained by the Society. In 1872, construction began

on their massive new full block facility on land granted by the state between East 68th and 69th

Streets and Lexington and Third Avenues. It opened in 1873, and an adoption department was

established to find permanent homes for children.

New York Foundling Hospital

circa

1894 - Byron

Company

Mt. St. Vincent

1846 Motherhood Home

1742 England

Foundling Home

1753 Foundling

England

St Vincent Day Home

Foundling Wheels

Foundling wheels were institutionalized by a papal bull issued in the

12th century by Pope Innocent III, who was shocked by the number of dead

babies found in the Tiber. By 1204, there was a wheel in operation at the

Santo Spirito Hospital in Rome, next to the Vatican. A 14th-century home

for abandoned children in Naples, annexed to a church, is now a museum

about foundlings. Many common family names in Italy can be traced to

a foundling past: Esposito (because children were sometimes “exposed”

on the steps of a convent), Proietti (from the Latin proicio, to throw away)

or Innocenti (as in innocent of their father’s sin).

In the Middle Ages, new

mothers in Rome could abandon their unwanted babies in a “foundling

wheel” — a revolving wooden barrel lodged in a wall, often in a convent,

that allowed women to deposit their offspring without being seen. Now a Rome hospital, the

Casilino Polyclinic, has introduced a technologically advanced version of the foundling wheel

— not at all a wheel but very much like an A.T.M. booth!

United States – Baby hatches started operating in the state of Indiana

in 2016. All 50 states have introduced “safe-haven laws” since Texas

began on September 1, 1999. These allow parents to legally give up

their newborn child (younger than 72 hours) anonymously to certain

places known as “safe havens”, such as fire stations, police stations,

and hospitals. Foundling wheels spread to various parts of Europe

and were used until the late 19th century. Modern foundling wheels

have made a comeback in various places in Europe in recent decades, particularly in Germany. Switzerland, the Czech Republic and other European countries also have drop-off points for unwanted

newborns. On mainland Italy and the island of Sicily, installed a device called ‘la ruota (or rota) dei

proietti’: the wheel of the castoffs, or ‘the foundling wheel’. These wheels could be in the outside

walls of churches or convents, or in larger cities, in the walls of foundling hospitals or orphanages.

The wheel was a kind of ‘lazy Susan’ that had a small platform on which a baby could be placed,

then rotated into the building, without anyone on the inside seeing the person abandoning the

child. That person then pulled a cord on the outside of the building, causing an internal bell

or chimes to ring, alerting those inside that an infant had been deposited. In the larger towns,

foundlings were baptized, then kept in a foundling home with others, and fed by wet-nurses in

the employ of the home. There they may have stayed for several years until they were taken by

townspeople as menial servants or laborers, or placed with a foster family. Or, sadly but more

likely, they never left the institution, having died from malnutrition or from diseases passed on

by the wet-nurses. In smaller towns, the foundling wheel may have been in the wall of the residence of a local midwife. She would have received the child, possibly suckled it immediately to

keep it alive, or arranged for a wet-nurse to do so, then taken it to the church to be baptized and

to the town hall to be registered. If the child was near death when found, many midwives were

authorized by the church to baptize the infant, ‹so that its soul would not be lost›. Civil officials

were often similarly authorized. Sometimes children were literally abandoned on the street or

on a doorstep, but the use of the foundling wheel was so widespread that even these children

were often referred to as having been ‹found in the wheel›.

next

Insane Insane Asylums

of the 19th Century

No comments:

Post a Comment