The Ancient Giants Who Ruled America

by Richard J Dewhurst

8

TREASURES OF GIANT BURIAL GROUNDS

The majority of sites that reveal burials of giants also yield evidence of a very sophisticated material

culture. The following story gives a reconstruction of the amazing finds made at the extensive complex of

mounds in the vicinity of Charleston, West Virginia. These mounds were first breached and studied in

1838 by the state’s geological survey team and later by the Smithsonian in 1883. This report is from a

front page feature in the state’s largest and most respected newspaper at the time, and because it is so

precise and detailed and, in many cases, straight from the Smithsonian’s own report, I will be quoting

from it at length.

THE GIANTS WERE FINE ARTISANS

CHARLESTON DAILY MAIL, SEPTEMBER 23, 1923

Among the most interesting artifacts unearthed were three worked and shaped pieces of cannel coal, a

special finely-textured variety of bituminous, which may have come from one of the outcroppings along

our local streams.

One was in pendant form, one a disc, and the third of no particular form, probably unfinished.

Fragments of seven stone and five clay pipes were found. There were two splendid bone fish hooks and

many bone awls and pins. Clay balls about the size of marbles may have been used in children’s games.

Miniature “toy” pottery vessels were discovered. Objects of worked antler included a chisel, projectile

points, and flakers. There were 341 triangular flint projectile points and 90 flint projectile points of other

types. Stone celts, adzes, balls, and a perforated stone disc were brought to light. Other discs of

perforated mussel shell were found. A study of the animal and bird bones indicated that the white-tailed

deer was very common, also wild turkey, elk and black bear to a lesser extent. Evidence of animals no

longer here included elk (28 fragments), bobcat (five fragments), wolf (one) and beaver (eleven).

FOUR HUNDRED SKELETONS UNEARTHED

AT ALABAMA MOUND

BY JEROME SCHWEITZER

UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA, FEBRUARY 27, 1930

EXCAVATIONS OF MUSEUM AT MOUNDVILLE PRODUCE 400 INDIAN

SKELETONS—7'6" GIANT AMONG THEM

Some 400 skeletons, the sizes of which vary from unborn infants to male adults and whose ages were

estimated at 1,000 to 5,000 years, have been uncovered at the Indian mounds at Moundville by the

Alabama Museum of Natural History. From his offices at the University of Alabama, Walter B. Jones,

director of the museum, announced that one skeleton measured seven feet six inches in height.

The museum party, headed by Director Jones and Curator William L. Halton and consisting of David de

Jarnette, assistant curator, and Carl T. Jones, topographer, is completing its first period of excavations.

The party is digging in an area recently purchased by the Museum and which has been designated as

Moundville. In addition to the remains of 400 Indians, the excavation party has taken from the mounds

hundreds of valuable artifacts.

AVERAGE HEIGHT OVER SIX FEET

All skeletons unearthed whose bones were strong enough to be preserved have been brought to the

Museum. “Most of the large skeletons brought out were found in the vicinity of Mound ‘G,’” Dr. Jones

said, “the majority averaging over six feet or more in height. All of the graves from which the skeletons

were taken were earthen except one, which was a very fine type of stone box burial, which is so prevalent

in Tennessee and Kentucky. As a whole the teeth were in very remarkable condition.”

Fig. 8.1. Archaeologists have said this stone duck bowl found at Moundville is arguably the most significant prehistoric

artifact ever found in the United States (courtesy of Jeffrey Reed).

A MYSTERIOUS STONE DISC UNDER ONE SKULL

One of the most remarkable burials encountered was that of a very prominent member of the tribe,

possibly the chief of a tribe that resided around Mound “E.” This burial carried a stone disc under the

skull, two square pots, and three miscellaneous pots; this pottery is superb ware and beautiful in design.

In addition, the skeleton wore many shell beads at the neck, the wrists and there were seven beads on

the right ankle and eleven on the left.

COPPER IS THE ONLY METAL FOUND

The only metal encountered during the excavations was copper, which appeared to be a great favorite

with the mound builders.

Red, yellow, and other pigments were met with everywhere, and all discs showed the presence of

white to pearl-gray paint, possibly made of lead carbonate, showing that these people carried on

elaborate rituals and procedures.

HUNDREDS OF ANCIENT ARTIFACTS FOUND

Director Jones announced that among the group of artifacts, 150 pots of various kinds, four pipes, ten

stone discs, one copper pendant, six copper ear plugs, about seventy-five bone awls or piercing

instruments, 100 discoidal stones, some made from igneous rocks brought in from other localities,

thousands of shell beads ranging from one and one half inches in length to very minute objects. Many of

the beads were spool shaped, some discoidal, others irregular.

FOODS WERE PLENTIFUL—REFUSE CAREFULLY BURIED

Their foods consisted of the meats of various animals, fowls, and fresh-water mussel shells. The latter

type of food was duplicated in one very fine vessel of earthenware. Numerous bones of deer, bear, turkey,

and fish were found with burials in pots and in dumps bordering the burial ground. Incidentally, the

dumps, or refuse heaps, appeared to have been buried the same as the human bodies.

Fig. 8.2. Engraved stone palette from Moundville, illustrating a horned rattlesnake, perhaps from the great serpent of the

southeastern ceremonial complex (courtesy of Jeffrey Reed)

REMARKABLE SQUARE POT RECOVERED

The most remarkable object met with by the party was a square pot, ornamented by brilliant red and

pearl-gray circles. Each circle was fringed by a pearl-gray ring. This is perhaps the finest vessel ever to

be taken from Moundville. Several other colored pots were encountered, several of which were very

remarkable. In 1904–05, Dr. Clarence Moore, connected with the Philadelphia Academy of Sciences,

found only three colored pots, and these were rather rude.

VARIOUS ANIMAL EFFIGIES AT MOUNDVILLE FIND

The art of the mound builders is characterized by various effigies including human heads and sometimes

bodies, heads of ducks, owls, alligators, frogs, fish, eagles, serpents, rattle snakes, etc. The rattle snake is

often portrayed as having horns and wings, making up what is termed the “flying circle.”

The party secured three excellent frog bowls. Although the Indians sometimes exaggerated certain

features, there is no question about the great accuracy of their artistic endeavors.

CLAY BRICK FOUND IN MOUND

On Mound “B,” 57 feet in height and one of the most remarkable Indian mounds in the world, were found

several pots probably placed there during some ceremonial rites, for no human bones were found with

them and the pits in which they had been placed were carefully covered with a very nice type of clay

brick.

The party was able to spot 33 distinct mounds within the area. Of the 33, the hollow square consists of

16 prominent mounds on the circumference with the largest and finest within the square. It is assumed that

the Chief lived on the high mound overlooking the entire area and that tribal ceremonies were carried on

upon the great mound just to the south of the Chief’s abode. It is further assumed that lesser Chiefs

occupied the lesser mounds, while the villagers lived in the areas adjoining the mounds. The northern rim of the hollow square overlooks the Black Warrior River. The entire plain is well above high water level.

In 1871, a Canadian newspaper article reported on a find from Cayuga, New York, in which two

hundred skeletons were removed from a collapsed mound. . . . These skeletons were said to be in a

perfect state of preservation and that “the men were of gigantic stature, some of them measuring nine feet,

very few of them being less than seven feet.”

NIAGARA’S ANCIENT CEMETERY OF GIANTS

DAILY TELEGRAPH, TORONTO,

ONTARIO, AUGUST 23, 1871

A REMARKABLE SIGHT:

TWO HUNDRED SKELETONS IN CAYUGA

TOWNSHIP

A SINGULAR DISCOVERY BY A TORONTONIAN AND OTHERS—A VAST

GOLGOTHA OPENED TO VIEW—SOME REMAINS OF THE "GIANTS THAT WERE

IN THOSE DAYS” FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENTS.

Cayuga, New York: On Wednesday last, Rev. Nathaniel Wardell, Messers Orin Wardell (of Toronto), and

Daniel Fredenburg were digging on the farm of the latter gentleman, which is on the banks of the Grand

River, in the township of Cayuga.

When they got to five or six feet below the surface, a strange sight met them. Piled in layers, one upon

top of the other, were some two hundred skeletons of human beings nearly perfect: around the neck of

each one being a string of beads.

There were also deposited in this pit a number of axes and skimmers made of stone. In the jaws of

several of the skeletons were large stone pipes, one of which Mr. O. Wardell took with him to Toronto a

day or two after this Golgotha was unearthed.

These skeletons are those of men of gigantic stature, some of them measuring nine feet, very few of

them being less than seven feet. Some of the thigh bones were found to be at least a foot longer than those

at present known, and one of the skulls being examined completely covered the head of an ordinary

person.

These skeletons are supposed to belong to those of a race of people anterior to the Indians.

Some three years ago, the bones of a mastodon were found embedded in the earth about six miles from this spot. The pit and its ghastly occupants are now open to the view of any who may wish to make a visit

there.

EARLY EASTERN OUTPOST FOR THE MOUND BUILDERS

The primacy of river routes in relationship to the placement of mound builder sites can be seen

everywhere in the United States. In this case the Allegheny River is singled out as a major ingress route

into western Pennsylvania and New York State.

RICH BURIALS AT SUGAR RUN ATTRACT SMITHSONIAN

On October 20, 1941, we have this report on the Smithsonian’s involvement in excavations at the Sugar

Run Indian Mounds in Warren, Pennsylvania, by Dr. Wesley Bliss and Edmund Carpenter, in association

with the state historical commission and representatives from the Smithsonian, including Dr. William N.

Fenton.

The central or most important find, was of two rock cists each containing an uncremated skeleton in

good preservation. Deposited with one of these, beneath the skull, were fifty-three cache blades; near

its feet, quantities of red and yellow ochre, a gorget and a sheet of mica. Near the center of the same

burial was a lump of galena (crystal lead). Mica, and cache blades were found, too, with the second

skeleton.

The earlier Sugar Run people appear to represent an eastern outpost for the “mound builders” of

the Mississippi drainage basin. The Allegheny River suggests itself as the corridor through which

these people penetrated into Western Pennsylvania and New York. These people probably flourished

until at least 1000 CE.

No intimate connection can be traced between the mound builders of Sugar Run and the

“Cornplanter” band or the other Senecas living just across the line in New York State. The former

appear to have lived along and disappeared from the upper Allegheny many years before the

ancestors of the present Senecas first appeared hereabouts.

MATERIAL TO BE CATALOGUED AND

PLACED IN SMITHSONIAN MUSEUM

As we have seen time and time again in this book, major caches of archaeological material are handed

over to the Smithsonian, only later to disappear down the memory hole of traditional research. The article

by Fenton continues . . .

“Material recovered from this site will be studied by experts over several months,” said Dr. C. E.

Schaeffer of the state historical commission in a speech also attended by Dr. William N. Fenton of the

Smithsonian, who was there to consult as a Seneca specialist

When the returns are all in formal reports of the investigations will be published and distributed in

professional quarters to make the information available to archaeologists in other areas. Leaflets,

illustrated talks, exhibits, and the like, will be prepared for the non-professional.

Finally, the artifacts will be placed in permanent storage or on exhibition at some central

repository for the benefit of the serious or casual student of archaeology.

1880 HISTORY OF INDIANA COUNTY

REVEALS INDIAN LORE

A great deal of local Indian lore is recorded in the old 1880 History of Indiana County. A few colorful

Indian names have continued until the present, reminding us of earlier times. The name “Kiskiminetas” is

of Indian origin, but there is some difference of opinion as to its meaning. Based on stem words from the

Indian language, one meaning is “plenty of walnuts.” Rev. John Heckewelder, a Moravian missionary

from the time of the Revolutionary War, said it meant “make daylight.” John McCullough, captured in

Franklin County by Indians in 1756, wrote of being taken to an old-town at “Keesk-kshee-man-nit-teos,”

meaning “cut spirit” and located at the junction of the Loyalhanna and the Conemaugh. Conemaugh is also

a name of Indian origin and means “long fishing place” or “otter creek.”

SEVENTEEN BURIALS UNCOVERED

As we begin to catalogue the mound builder burial practices, one of the major burial styles is “flexed”

burial, where the knees are drawn up to the chest.

Seventeen burials were uncovered in the excavated portions of the tract; ten children and infants, four

adult males, two adult females, and one unidentified adult. “Most had been buried in a flexed position,

with knees dawn up to the chest.”

THE MISSING GIANTS IN NORTH CAROLINA

In North Carolina, significant finds were made in the Yadkin Valley of Caldwell County in 1883 that

included one group of four skeletons in seated positions and a pair lying on their backs. One of the

recumbent skeletons was of a man who was reported to be seven feet tall. At another site in the North

Carolina foothills, twenty-six skeletons were found in unusual burial positions associated with other

mound builder sites. In yet another location, sixteen skeletons were found in seated, squatting, and prone

positions in the center of which was a skeleton standing upright in a large stone cist, which is a burial

chamber made of stone or a hollow tree.

The following section is from an October 18, 1962, Associated Press article that includes extensive

quotes from a report written for the Smithsonian. It was published in the North Carolina–based Lenoir

News and the Virginia Bee and was also syndicated nationally. This article is of great interest as it

documents the Smithsonian’s involvement in the dig, as well as the institution’s confiscation of the

evidence for further study.

SIXTEEN NORTH CAROLINA SKELETONS SHIPPED

TO THE

SMITHSONIAN

BY NANCY ALEXANDER

ASSOCIATED PRESS, OCTOBER 18, 1962

In 1883 the foothill section of North Carolina became the site of intense excavations for Indian relics. Dr.

James Mason Spainhour, a Lenoir dentist and Indian authority, discovered several large mounds in the

area. Relics, which he and others unearthed, so aroused the interest of officials of the Smithsonian

Institution in Washington that a representative, J. P. Rogan, was sent to the area to assist with the

excavations.

Rogan wrote a comprehensive report of Caldwell County findings using sketches to illustrate each of

five notable mounds discovered. All were located in the Yadkin Valley area now known as Happy Valley.

After skeletons were carefully removed and labeled, they were sent to the Smithsonian. Later one of the

mounds was carefully reproduced in miniature for public viewing.

It was on the T. F. Nelson farm about a mile and a half southeast of Patterson, that two important

discoveries were made. “The first mound was only about 18 inches in height from first appearances,”

writes Rogan. “Of circular shape it was about 38 feet in diameter. A pit had been dug about three feet

deep, with the center area being about six feet in depth.

“Sixteen skeletons were found in various positions, some squatting, some reclining, while others were

in small stone sepultures of water-worn rocks,” continues Rogan in the official Smithsonian report. “In the

center was a skeleton standing upright in a large stone cist. Also found were stones shaped like disks and

pitted. There were celts, crude bones and soapstone pipes, black paint made from molded nuts and

charcoal.”

TWENTY-SIX-MORE NORTH

CAROLINA SKELETONS FOUND

“On the W. D. Jones property two miles east of Patterson, a fourth excavation was made,” reports Rogan

to the Smithsonian.

In a low circular mound about 32 feet in diameter and three feet in depth, 26 skeletons were

discovered. Relics included celts, disks, shell beads, food cups, crescent shaped pieces of copper, pipes,

red and black paint, broken pottery, and charcoal.

As a result of the excavations excitement spread throughout the region. People began exploring hillocks

and mounds in all vicinities. Other discoveries, which went unrecorded, were made. John P. Perry and

John M. Houck, exploring an old Indian camp site near the present Brown Mountain Beach, found many

relics.

THE MANY MOUNDS OF TENNESSEE

I have already included excerpts detailing some of the amazing accounts in Dr. John Haywood’s

wonderful book from 1823, The Natural and Aboriginal History of Tennessee. Perhaps the most amazing

finds described in the book were the tiny mounds that contained caskets of the three-foot-tall “moon-eyed

children,” who were pygmies that were said to accompany the giants. The three-foot-tall pygmies were

originally said to have come from North Carolina, and legends say they were mischievous and only liked

to come out at night. Comparisons with leprechauns immediately come to mind reading this. Cherokee

lore recounts that they waged war against these moon-eyed people and drove them from their home in

Hiwassee, a village in what is now Murphy, North Carolina, pushing them west into Tennessee.

In addition to numerous giants and pygmies, Haywood discovered grave goods, including bloody axes,

a stone trumpet hunting horn, carved mastodon bones, and soapstone statues and pipes. In a cave on the

south side of the Cumberland River, a secret room was discovered that was twenty-five feet square and

showed signs of engineering, as it contained a large rock-cut well and the skeleton of a blond-haired

giant.

Outside of Sparta, a standing stone was discovered that marked the burial of more oversized skeletons.

In another burial at the top of a nearby hill, carved ivory beads were found of the “finest and best quality,”

while in a dig at Ohio Falls, Roman coins depicting Claudius II and Maximinus II were uncovered. It was

reported that in 1794, an ancient furnace was discovered and in association with it a bar of iron was

found, as well as annealed and hardened copper implements.

The Natural and Aboriginal History of Tennessee, 1823

BY DR. JOHN HAYWOOD

It would be an endless labor to give a particular description of all the mounds in Tennessee. They are

numerous upon the rivers, which empty into the Mississippi, running from the dividing ridge between

that river and Tennessee. They are found upon Duck river, the Cumberland, upon the Little Tennessee

and its waters, and upon the Big Tennessee, upon French broad and upon Elk river.

Fig. 8.3. An illustration of the Tennessee dig led by Dr. John Haywood, 1823

The trees are of more recent growth which are upon the mounds that are found in the last settlements of

the Natchez; for instance, near the town of Natchez, and on the waters of the Mississippi within the

present limits of Tennessee than those are which grow upon the mounds in other parts of the country: a

circumstance, which furnishes the presumption, that the ancient builders of the latter were expelled from the other parts of Tennessee, at a period corresponding with the ages of the trees which the whites found

growing upon them.

A careful description of a few of these mounds in West and East Tennessee will put us in possession of

the properties belonging to them generally. In the county of Sumner, at Bledsoe’s lick, eight miles

northeast from Gallatin, about 200 yards from the lick, in a circular enclosure, between Bledsoe’s lick

creek and Bledsoe’s spring branch, upon level ground, is a wall 15 or 18 inches in height, with projecting

angular elevations of the same height as the wall and within it, are about 16 acres of land.

Fig. 8.4. Engraved shell from a Tennessee mound, from The Problem of the Ohio Mounds by Cyrus Thomas, Smithsonian

Institute, 1889

In the interior is a raised platform, from 13 to 15 feet above the common surface, about 200 yards

from the wall to the south, and about 50 from the northern part of it. This platform is 60 yards length

and breadth, and is level on the top. And is to the east of a mound to which it joins, of 7 or 8 feet

higher elevation, or 8 feet from the common surface to the summit, about 20 feet square. On the

eastern side of the latter mound, is a small cavity, indicating that steps were once there for the

purpose of ascending from the platform to the top of the mound.

In the year 1785, there grew on the top of the mound a black oak three feet through. There is no

water within the circular enclosure or court. Upon the top of the mound was ploughed up some years

ago, an image made of sandstone. On one cheek was a mark resembling a wrinkle, passing

perpendicularly up and down the cheek. On the other cheek were two similar marks. The breast was

that of a female, and prominent. The face was turned obliquely up, towards the heavens. The palms of

the hands were turned upwards before the face and at some distance from it, in the same direction that

the face was. The knees were drawn near together, and the feet, with the toes towards the ground,

were separated wide enough to admit of the body being seated between them.

The attitude seemed to be that of adoration. The head and upper part of the forehead were covered

with a cap or mitre or bonnet from the lower part of which came horizontally a brim, from the

extremities of which the cap extended upwards conically. The color of the image was that of a dark

infusion of coffee. If the front of the image was placed to the east, the countenance obliquely

elevated, and the uplifted hands in the same direction would be toward the meridian sun.

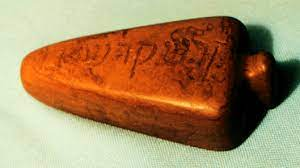

About ten miles from Sparta, in White county, a conical mound was lately opened, and in the center

of it was found a skeleton eight feet in length. With it was found a stone of the flint kind, very hard,

with two flat sides, having in the center circular hollows exactly accommodated to the balls of the

thumb and forefinger. This stone was an inch and a half in diameter, the form exactly circular. It was

about one third of an inch thick, and made smooth and flat, for rolling, like a grindstone, to the form

of which, indeed, the whole stone was assimilated. When placed upon the floor, it would roll for a

considerable time without falling.

The whole surface was smooth and well-polished, and must have been cut and made smooth by

some hard metallic instrument. No doubt it was buried with the deceased, because for some reason

he had set a great value on it in his lifetime, and had excelled in some accomplishment to which it

referred.

The color of the stone was a dingy white, inclining to a darkish yellow. At the side of this skeleton

were also found two flat stones, about six inches long, two and a half wide at the lower part, and

about one and a half at the upper end, widening in the shape of an ax or hatchet from the upper to the

lower end. The thickness of the stone was about one tenth of an inch. An inch below the upper end

exactly equidistant from the lateral edges, a small hole is neatly bored through each stone, so that by a

string run through, the stone might be suspended off the side or from the neck as an ornament.

One of these stones is the common limestone. The other is semitransparent, so as to be darkened by

the hand placed behind it and resembles in texture those stalactical formations, like white stone,

which are made in the bottoms of caves by the dripping of water. When broken, there appears a grain

running from one flat side to the other, like the shootings of ice or saltpeter, of a whitish color

inclining to yellow. The latter stones are too thin and slender, for any operation upon other

substances, and must have been purely ornamental.

The first described stone must have been intended for rolling.

For why take so much pains to make it circular, if to be used in flinging? Or why, if for the latter

purpose, so much pain taken to make excavations adapted to the thumb and finger. The conjecture

seems to be a probable one that it was used in some game played upon the same principles as that

called ninepins; and the little round balls, like marbles, but of a larger size, were so disposed as that

the rolling stone should pass through them.

Such globular stone, it is already stated, was found in a mound in Maury County. With this large

skeleton were also found eight beads and a human tooth. The beads were circular and of a bulbous

form. The largest about one fourth of an inch in diameter, the others smaller. The greater part of them

tumescent from the edge to the center, at which a hole was perforated for a string to pass through and

to connect them. The inner sides were hard and white, like lime indurated by some chemical process.

The outside was a thin coal of black crust.

OKLAHOMA PICTURE WRITING

BY RAY E. COLTON

MIAMI, OKLAHOMA, DECEMBER 10, 1939

Yes! The tombs of a long-vanished race of mound builders have been found near Langley, in Mayes

County, site of the Grand River dam, and much is expected to be learned from these finds after

investigating archaeologists and anthropologists complete their studies of the finds which have been

made.

The pottery, consisting of drinking vessels, water bowls, and so forth has been found in the excavated

mounds near Langley, and also recently in mounds unearthed near Grove in Delaware County, even to

designs such as the Thunder Bird. Arrow heads, which have been found at Langley and also in the Grove

“diggings,” are of many designs and sizes.

In the slender fishing or hunting point type, made of some material resembling glass, the symmetry and

design are perfect, thus reflecting a remarkable degree of ability on the part of the manufacturers. Battle or

war points, ranging in size from eight to ten inches, and about two inches in width at their widest point

near the center, are of two types of material, namely obsidian “black” and flint “gray.” A study in the area

of the vicinity of these finds by geologists fails to show any material corresponding to these types of

rocks, and on the basis of these finds, it is assumed that the material to make these points was brought

from some distant point in either southern Kansas or central Missouri, where some of this material exists.

The balance of the war points is perfect and when held in the palm of the hand, remains in a perfect

balanced position.

Picture writings which have been found near Grove show in crude design a hunter chasing a buffalo

with a spear of this type.

MUCH LARGER THAN PRESENT-DAY HUMANS

Some of the burials, which have been unearthed at the dam site, appear with head to the north, while

others appear with head to the south. The meaning of this has not been determined. Some evidences of the

practice of masonry are noted in some of the finds, and it is believed that the mound builders had

knowledge of this craft. Certain skeleton remains have considerable arrow heads, beaded work, and other

artifacts around them. It is theorized that the person possessed some rank of standing within the tribal

councils and was thus designated by the artifacts buried with him.

Fig. 8.5. Examples of copper and stone work: pre-Columbian copper artifacts from Oklahoma, Missouri, and Illinois

(courtesy of Herb Roe)

Most of the skeleton remains are much larger than present day humans and the race must have presented

a strange sight owing to the extreme heights of its members.

A GIANT RACE

MEMPHIS DAILY APPEAL, AUGUST 15, 1870

THE INDIAN MOUND CHICKASAWBA

HUMAN SKELETONS EIGHT AND TEN

FEET

IN HEIGHT—RELICS OF A FORMER AGE

Two miles west of Barfield Point, in Arkansas County, Ark., on the east bank of the lovely stream called Pemiscot River, stands an Indian mound, some 25 feet high and about an acre in area at the top.

This mound is called Chickasawba, and from it the high and beautiful country surrounding it, some

twelve square miles in area derives its name: Chickasaw. The mound derives its name from Chickasawba, a chief of the Shawnee tribe, who lived, died, and was buried there.

STILL ACTIVE AS TRADING MOUND IN 1820

From 1820 to 1831, Chickasawba and his hunters assembled annually at Barfield Point, then, as now, the

principal shipping place of the surrounding country, and bartered off their furs, peltries, buffalo robes, and

honey to the white settlers and the trading boats on the river, and receiving in turn powder, shot, lead,

blankets, money, etc.

A GIANT EIGHT TO NINE FEET TALL IS FOUND

A number of years ago in making an excursion into or near the foot of Chickasawba’s mound, a portion of

a gigantic human skeleton was found. The men who were digging, becoming interested, unearthed the

entire skeleton, and from measurements given to us by reliable parties the frame of the man to whom it

belonged could not have been less than eight or nine feet in height.

Under the skull, which easily slipped over the head of our informant (who, we will here state, is one of

our best citizens) was found a peculiarly shaped earthen jar, resembling nothing in the way of Indian

pottery, which had before been seen by them.

It was exactly the shape of the round-bodied, long-necked carafes or water-decanters, a specimen of

which may be seen on Gaston’s table.

EXQUISITE HIEROGLYPHS FOUND

ON FINELY-CARVED VASE

The material of which the vase was made was of a peculiar kind of clay, and the workmanship was very

fine. The belly or body of it was ornamented with

FIGURES OR HIEROGLYPHICS

consisting of a

correct delineation of human hands, parallel to each other, open, palms outward, and running up and down

the vase, the wrists to the base, the fingers towards the neck. On either side of the hands, were tibia or

thigh bones, also correctly delineated, running around the base.

MORE SKULL, MORE VASES UNDER THEIR HEADS

Since that time, whenever an excavation has been made in Chickasawba country in the neighborhood of

the mound SIMILAR SKELETONS have been found and under the skull of every one were found similar

funeral vases, almost exactly like the one described. There are now in the city several of the vases and

portions of the huge skeletons. One of the editors of The Appeal yesterday measured a thighbone, which is

fully three feet long.

The thigh and shin bones, together with the bones of the foot, stood up in proper position in a

physician’s office in this city, measure five feet in height, and show the body to which the leg belonged to

have been from nine to ten feet in height. At Beaufort’s Landing, near Barfield, in digging a deep ditch, a

skeleton was dug up, the leg of which measured from five to six feet in length and other bones in

proportion.

THREE

Pre-Columbian Foreign Contact

9

HOLY STONES, A CALENDAR STELE,

AND FOREIGN COINS

As we have seen, there is compelling evidence that America’s giants belonged to sophisticated

indigenous cultures. Along with that there are strong indications of very ancient cultural exchanges with

other parts of the world. In this chapter I review reports related to tablets carved with inscriptions, a

calendar stele, and ancient foreign coins.

GEORGE S. MCDOWELL REVEALS HIEROGLYPHIC TABLETS IN THE POSSESSION OF

THE CINCINNATI SOCIETY OF NATURAL HISTORY

One of the most extraordinary documents I have run across in my research is a newspaper article

published in 1891, which goes into a detailed description and translation of tablets in the possession of a

historical society’s museum in Cincinnati, textiles matching those in Assyria, evidence of surgery, and so

forth. The author was a respected writer, and the article was widely syndicated nationally in 1891.

RARE TREASURES CONTAINED IN THE MUSEUM OF THE CINCINNATI

SOCIETY OF NATURAL HISTORY

BY GEORGE S. MCDOWELL

CINCINNATI ENQUIRER, JULY 15, 1891

FURTHER EXPLORATIONS NOW IN PROGRESS IN OHIO

Continued explorations among the ancient monuments remaining in the Ohio valley maintain the general

interest in those people whose existence was before the time of written history, whose relations to the rest

of mankind have never been discovered, and who are distinguished simply as mound builders; that is, they

are known only as the authors of the most enduring of the monuments that survive them: those great piles

of earth, whether raised for sacrifice, sepulture, or war.

The museum of the Cincinnati Society of Natural History is filled with a wealth of these curious

peoples, in many cases inexplicable antiquities, and the explorations, which are in progress among the

mounds and forts of the Little Miami Valley, under the direction of Dr. Metz, of Madisonville, Ohio, are

almost every day bringing to light additions to the remarkable collection, which is equaled only by the one

at the Peabody Museum, that was filled and still supplied by the same sources.

A study of these shows that the mound builders were an agricultural people, industrious in the arts of

peace as well as the precautions of war, with considerable educational and scientific attainments, and that

they had rites and ceremonies of religion and burial as distinctive as any that characterize the people of

the present day.

ROWS AND ROWS OF GRINNING SKULLS

Illustrative of the physical characteristics of the people, the Cincinnati Museum has a number of skeletons

taken from the mounds around the city and the newly-excavated cemetery near Madisonville, and there are

rows upon rows of grinning skulls from which the learned members of the society have drawn many

lessons touching on the mental qualifications of these ancient people.

They have determined that the shape and the phrenological points preclude the possibility to their

having belonged to any Indians of whom our histories furnish us information.

There is also in the rooms of the society a piece of woven cloth taken from one of the mounds, in this

case found lying close to a skeleton that occupied almost the center and bottom of the mound (so that it

must have been placed there with the corpse) that in texture is almost identical with cloth found among the

ruins of ancient Babylon and Assyria and the farther east.

Fig. 9.1. Cincinnati tablet. Sometimes referred to as the great American Rosetta stone, the Cincinnati tablet was discovered

in the Old Mound at the corner of Fifth and Mound Streets in Cincinnati in 1841. At first declared a fraud, it was later shown to

be authentic. Some have speculated that it is a stylized representation of the Tree of Life. (Illustration from Ancient

Monuments of the Mississippi Valley by Ephraim Squier and Edwin Davis.)

THE SENSATIONAL CINCINNATI TABLET

Similar to the textile in its ancient connections to advanced civilization, are two other relics in the

possession of the Society—one known as the “Conjuring Stone” and the other as the “Tablet of Life” or

more commonly the “Cincinnati Tablet” because it was taken from one of the mounds marking the site of

the city—the former a mathematical, the other a psychological witness.

The tablet is a remarkable and curious stone. Two others of similar hieroglyphical decoration, but

plainly of less advanced philosophical idea, according to the learned men who examined them have been

found in Ohio mounds, one near Wilmington and the other near Waverly.

And not only does the Cincinnati Tablet exhibit a more advanced idea, it is also of superior

workmanship and preservation. An examination of the drawing of the Cincinnati Tablet will discover

upon it several fetal designs that have been interpreted as symbolical of those gestative and procreative

mysteries that must have powerfully affected the minds of man in the remotest early ages. The design of

the tablet shows that its author had knowledge of the stages of development at various periods of fetal

growth, and the tablet, bearing these symbolizations of the existence before life, was no doubt used in

connection with the ceremonies of sepulture and possibly by way of comparative conjecture concerning

the hidden things of life beyond the grave.

THE MEASURING STONE

Regarding the next in importance to the “Tablet,” is the “Measuring Stone.” This is a piece of sandstone,

about exactly nine inches on the flat side and twelve inches on the curve, the dotted lines in the drawing

indicating the completed ellipse, which is an exact model of the mound in which it was found.

Learned mathematical analysis shows this stone to have been the basis for all measurements of the great

mounds and earthworks in the Ohio Valley, and that the same numbers 9 and 12 are the key numbers of the

measures used in the construction of the architectural works of the Chaldeans, Babylonians, pre-Semites,

and Egyptians, while the latter number remains to this day the English standard.

EVIDENCE OF BRAIN SURGERY

The skull taken from an excavation near Cincinnati shows that these people were well-versed in surgery.

It is the skull of a man who had once received a terrible blow to the side of the head, which crushed the

skull, but after careful treatment recovered from the effects of the blow. Dr. Langdon, an eminent surgeon

of Cincinnati, examined the skull and said that the adjustments to the parts of bone and the way in which

they had healed show knowledge of practical surgery scarcely excelled at the present day.

FORGES, POLISHING BONES, AND IRON

The relics in the Museum of the Cincinnati Society show also that these people were well-versed in the

industrial arts, there being the remains of hammers, knives, mica ornaments, beads, wampum, decorated

shells, pottery, and many other things. Among these are some that have puzzled the scientists to determine

to what uses they have been applied such as a certain leg bone.

It is a femur almost worn in two by some friction, as though it must have been used for polishing.

Thousands of pieces of these bones have been found, having been so worn away that they broke in use.

There is also a kind of needle, made from long fish bones resembling in length the present crocheting

needle and the carpet needle in construction. They may have been used in the making of clothing.

There are found the remains of forges, and great quantities of furnace slag and cinders and scaling like

those that fly from beaten white-hot iron.

HIEROGLYPHICS ALSO FOUND IN MARIETTA

It may be that one of the tablets with “similar hieroglyphical decoration” referred to by McDowell in

1891 is the one described below as part of the findings of an elaborate giant burial in Muskingum County,

Ohio.

REMAINS OF NINE-FOOT GIANTS IN OHIO

CINCINNATI ENQUIRER, JULY 14, 1880

(SEE MARION DAILY STAR,

JULY 14, 1880, FOR ORIGINAL STORY)

The mound in which these remarkable discoveries were made was about sixty-four feet long and thirty five feet wide top measurement and gently sloped down to the hill where it was situated. A number of

stumps of trees were found on the slope standing in two rows, and on the top of the mound were an oak

and a hickory stump, all of which bore marks of great age.

All of the skeletons were found on a level with the hill, and about eight feet from the top of the mound.

In one grave there were two skeletons, one male and one female. The female face was looking downward,

the male being immediately on top, with the face looking upward. The male skeleton measured nine feet in

length, and the female was eight.

The male frame in this case was nine feet, four inches in length and the female was eight feet.

In another grave was found a female skeleton, which was encased in a clay coffin, holding in her arms

the skeleton of a child three and a half feet long, by the side of which was an image, which being exposed

to the atmosphere, crumbled rapidly.

The remaining seven, were found in single graves and were lying on their sides. The smallest of the

seven was nine feet in length and the largest ten. One single circumstance connected with this discovery

was the fact that not a single tooth was found in either mouth except in the one encased in the clay coffin.

On the south end of the mound was erected a stone altar, four and a half feet wide and twelve feet long,

built on an earthen foundation nearly four feet wide, having in the middle two large flagstones, from which sacrifices were undoubtedly made, for upon them were found charred bones, cinders, and ashes.

This was covered by about three feet of earth.

AN ANCIENT TABLET WITH POSSIBLE HIEROGLYPHS

What is now a profound mystery may in time became the key to unlock still further mysteries that were

centuries ago commonplace affairs.

I refer to a stone that was found resting against the head of the clay coffin above described. It is

irregularly shaped red sandstone, weighing about 18 pounds, being strongly impregnated with oxide of

iron, and bearing upon one side TWO LINES OF HIEROGLYPHS.

HOLY STONES IN OHIO AND ILLINOIS?

Other ancient engraved tablets found in Ohio and Illinois deepen the mystery.

IS IT REALLY THE TEN COMMANDMENTS?

OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY WEB ARCHIVE

In November of 1860, David Wyrick of Newark, Ohio, found an inscribed stone in a burial mound about

ten miles south of Newark. The stone is inscribed on all sides with a condensed version of the Ten

Commandments or Decalogue, in a peculiar form of post- Exilic square Hebrew letters. The robed and

bearded figure on the front is identified as Moses in letters fanning over his head.

The inscription is carved into a fine-grained black stone. It has been identified by geologists Ken Bork

and Dave Hawkins of Denison University as limestone; a fossil crinoid stem is visible on the surface, and

the stone reacts strongly to HCl. It is definitely not black alabaster or gypsum as previously reported here.

According to James L. Murphy of Ohio State University, “Large white crinoid stems are common in the

Upper Mercer and Boggs limestone units in Muskingum Co. and elsewhere, and these limestones are often

very dark gray to black in color. You could find such rock at the Forks of the Muskingum at Zanesville,

though the Upper Mercer limestones do not outcrop much further up the Licking.” We therefore need not

look any farther than the next county over to find a potential source for the stone, contrary to the previous

assertion here that such limestone is not common in Ohio. The inscribed stone was found inside a

sandstone box, smooth on the outside and hollowed out within to exactly hold the stone. The Decalogue

inscription begins at the non-alphabetic symbol at the top of the front, runs down the left side of the front,

around every available space on the back and sides, and then back up the right side of the front to end

where it begins, as though it were to be read repetitively.

Fig. 9.2. The Newark “holy stone” (courtesy of J. Huston McCulloch)

David Deal and James Trimm note that the Decalogue stone fits well into the hand, and that the lettering

is somewhat worn precisely where the stone would be in contact with the last three fingers and the palm if

held in the left hand. Furthermore, the otherwise puzzling handle at the bottom could be used to secure the

stone to the left arm with a strap. They conclude that the Decalogue stone was a Jewish arm phylactery or

tefilla (also written t’filla) of the Second Temple period. Although the common Jewish tefilla does not

contain the words of the Decalogue, Moshe Shamah reports that the Qumran sect did include the

Decalogue.

THE KEYSTONE ALSO FOUND AT NEWARK MOUNDS

Several months earlier, in June of 1860, David Wyrick had found an additional stone, also inscribed in

Hebrew letters. This stone is popularly known as the “Keystone” because of its general shape. However,

it is too rounded to have actually served as a keystone. It was apparently intended to be held with the

knob in the right hand, and turned to read the four sides in succession, perhaps repetitively. It might also

have been suspended by the knob for some purpose. Although it is not pointed enough to have been a

plumb bob, it could have served as a pendulum.

The material of the Keystone has been identified, probably by geologist Charles Whittlesey,

immediately after its discovery as novaculite, a very hard fine-grained siliceous rock used for whetstones.

[For more on Whittlesey, see “Ancient Copper Mining in the Great Lakes,”.] The inscriptions on the four

sides read:

Fig. 9.3. The Keystone (courtesy of J. Huston McCulloch)

Qedosh Qedoshim, "Holy of Holies"

Melek Eretz, "King of the Earth"

Torath YHWH, "The Law of God"

Devor YHWH, "The Word of God"

Wyrick found the Keystone within what is now a developed section of Newark, at the bottom of a pit

adjacent to the extensive ancient Hopewellian earthworks there (circa 100 BC–AD 500). Although the pit

was surely ancient, and the stone was covered with 12–14 inches of earth, it is impossible to say when

the stone fell into the pit. It is, therefore, not inconceivable that the Keystone is genuine but somehow

modern.

The letters on the Keystone are nearly standard Hebrew rather than the very peculiar alphabet of the

Decalogue stone. These letters were already developed at the time of the Dead Sea Scrolls (ca. 200–100

BC), and so are broadly consistent with any time frame from the Hopewellian era to the present. For the

past 1000 years or so, Hebrew has most commonly been written with vowel points and consonant points

that are missing on both the Decalogue and Keystone. The absence of points is therefore suggestive, but

not conclusive, of an earlier date.

Note that in the Keystone inscription, “Melek Eretz,” the aleph and mem have been stretched so as to

make the text fit the available space. Such dilation does occasionally appear in Hebrew manuscripts of

the first millennium AD. Birnbaum, The Hebrew Scripts, vol. I, pp. 173–4, notes that “We do not know

when dilation originated. It is absent in the manuscripts from Qumran. . . . The earliest specimens in this

book are . . . middle of the seventh century [AD]. Thus we might tentatively suggest the second half of the

sixth century or the first half of the seventh century as the possible period when dilation first began to be

employed.” Dilation would not have appeared in the printed sources nineteenth-century Ohioans would

primarily have had access to.

The Hebrew letter shin is most commonly made with a V-shaped bottom. The less common flat bottomed form that appears on the first side of the Keystone may provide some clue as to its origin. The

exact wording of the four inscriptions may provide additional clues.

Today, both the Decalogue Stone and Keystone, or “Newark Holy Stones,” as they are known, are on

display in the Johnson-Humrickhouse Museum in Roscoe Village, 300 Whitewoman St., Coshockton,

Ohio.

THE WILSON MOUND STONES

One year after Wyrick’s death in 1864, two additional Hebrew-inscribed stones were found during the

excavation of a mound on the George A. Wilson farm east of Newark. These stones have been lost, but a

drawing of the one and a photograph of the other are reproduced in Alrutz.

The two stones from the Wilson farm, known as the “Inscribed Head” and the “Cooper Stone” at first

caused considerable excitement. Shortly afterwards, however, a local dentist named John H. Nicol

claimed to have carved the stones and to have introduced them into the excavation, with the intention of

discrediting the two earlier stones found by Wyrick.

The inscription on the Inscribed Head can be read in Hebrew letters as J–H–NCL.In Hebrew, short

vowels are not represented by letters, so this is precisely how one would write J–H–NiCoL.

The Cooper stone is less clear, but appears to have a similar inscription. The inscriptions themselves

therefore confirm Nicol’s claim to have planted these two stones. Nicol was largely successful in his

attempt to discredit the Wyrick stones, and they quickly became a textbook example of a “well-known”

hoax. It was only with Alrutz’s thorough 1980 article

*3

that interest in them was revived.

Although the Decalogue is of an entirely different character than either of the Wilson Mound stones, it

is disturbing that Nicol was standing near Wyrick at the time of its discovery.

THE JOHNSON-BRADNER STONE

Two years later, in 1867, David M. Johnson, a banker who co-founded the Johnson-Humrickhouse

Museum, in conjunction with Dr. N. Roe Bradner, M.D., of Pennsylvania, found a fifth stone, in the same

mound group south of Newark in which Wyrick had located the Decalogue. The original of this small

stone is now lost, but a lithograph, published in France, survives.

The letters on the lid and base of the Johnson-Bradner stone are in the same peculiar alphabet as the

Decalogue inscription, and appear to wrap around in the same manner as on the Decalogue’s back

platform. However, the lithograph is not clear enough for me to attempt a transcription with any

confidence. However, Dr. James Trimm, whose Ph.D. is in Semitic Languages, has recently reported that

the base and lid contain fragments of the Decalogue text. The independent discovery, in a related context,

by reputable citizens, of a third stone bearing the same unique characters as the Decalogue stone, strongly

confirms the authenticity and context of the Decalogue Stone, as well as Wyrick’s reliability.

Fig. 9.4. Ancient Works at Newark. This map was published in the 1866 Newark County Atlas.

Fig. 9.5. These skeletons found in a recent excavation in Germany are from the Neolithic Period and are typical of the

multiple burials found in many of America’s Indian mounds (courtesy of Arthur W. McGrath).

Fig. 9.6. Lithograph by Nancy J. Royer, Congres International des Americanistes (courtesy of J. Huston McCulloch)

Mr. Myron Paine of Martinez, Calif., has cogently noted that the Johnson-Bradner stone, if bound in a

strap so as to be held as a frontlet between the eyes, would serve well as a head phylactery, while the

Decalogue stone was being used as an arm phylactery per the Deal-Trimm hypothesis noted in the first

section above.

THE MYSTERIOUS STONE BOWL

A stone bowl was also found with the Decalogue, by one of the persons accompanying Wyrick. By

Wyrick’s account, it was of the capacity of a teacup, and of the same material as the box. Wyrick believed

both the box and the cup had once been bronzed (Alrutz, pp. 21–2), though this has not been confirmed.

The bowl was long neglected, but was found recently in the storage rooms of the Johnson-Humrickhouse

Museum by Dr. Bradley Lepper of the Ohio Historical Society. It is now on display along with the

Decalogue stone and Keystone. (Photo courtesy of Jeffrey A. Heck, Najor Productions, njor@tcon.net).

An interview in the Jan/Feb 1998 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review (“The Enigma of Qumran,” pp.

24ff.) sheds light on the possible significance of the stone bowl. The interviewer, Hershel Shanks, asked

how we would know that Qumran, the settlement adjacent to the caves in which the Dead Sea Scrolls

were found, was Jewish, if there had been no scrolls. The four archaeologists interviewed gave several

reasons: the presence of ritual baths, numerous Hebrew-inscribed potsherds, and its location in Judea,

close to Jerusalem. Then Hanan Eshel, senior lecturer in archaeology at Hebrew University and Bar-Ilan

University, gave a fourth reason.

Fig. 9.7. The Decalogue stone, the Keystone, and the ritual cleansing bowl (photo by Jeffrey A. Heck)

ESHEL: We also have a lot of stone vessels.

SHANKS: Why is that significant?

ESHEL: Stone vessels are typical of Jews who kept the purity laws. Stone vessels do not become

impure.

SHANKS: Why?

ESHEL: Because that is what the Pharisaic law decided. Stone doesn’t have the nature of a vessel, and

therefore it is always pure.

SHANKS: Is that because you don’t do anything to transform the material out of which it is made, in

contrast to, say, a clay pot, whose composition is changed by firing?

ESHEL: Yes. Probably. Stone is natural. You don’t have to put it in an oven or anything like that. Purity

was very important to the Jews in the Late Second Temple period.

In an article in a subsequent issue of BAR, Yitzhak Magen goes on to explain that in the late Second

Temple period, the Pharisees ordained that observant Jews should ritually rinse their hands with pure

water before eating, and that in order to be pure, the water had to come from a pure vessel. Pottery might

be impure, but stone was always pure. The result was a brief “Israeli Stone Age,” during which there

flourished an industry of making stone teacups to pour the water from and stone jugs to store it in. After

the destruction of the Second Temple in AD 70, this practice quickly disappeared.

The stone bowl therefore fits right in with the Decalogue Stone as an appropriate ritual object. It is

highly doubtful that Wyrick, Nicol, McCarty, or anyone else in Newark in 1860 would have been aware

of this arcane Second Temple era convention.

Perhaps the stone box is another manifestation of the same “Stone Age” imperative: The easy way to

make a box to hold an important object (or a prank) is out of wood. Carving it from stone is unnecessarily

difficult, and would be justified only if stone were regarded as being significant in itself. According to

Wyrick the bowl and box were made of the same sandstone.

Two unusual “eight-square plumb bobs” were also found with the Decalogue. Their location is

unknown, though they might also turn up in the Museum’s collections.

HUNTERS FIND STONE TABLETS UNDER A TREE

SMITHSONIAN INVOLVED IN ILLINOIS TABLET FIND

A REMARKABLE FIND ON THE PRAIRIES OF

ILLINOIS: QUAINT LETTERING,

INDIAN RELICS,

AND THE MOUND BUILDERS

CHICAGO TRIBUNE, AUGUST 10, 1892

A remarkable discovery was recently made on the virgin field a few miles from LaHarpe, in the historic

old county of Hancock, in Illinois. Wyman Huston and Daniel Lovitt were chasing a ground squirrel on the

farm of Huston, when the dog trailed the squirrel to its hole under an old dead tree stump, which was

easily pushed over by one of the men. In grabbing for the squirrel, the old stump was taken out, and under

its roots were found two sandstone tablets, about 10 × 11 inches, and from one-fourth to half-an-inch in

thickness.

The tablets lay one upon the other, and the sides that faced contained strange inscriptions in Roman-like

capital letters that had been cut into the stone with some sharp instrument. The men brought the tablets to

LaHarpe, where they were inspected by several antiquarians but none of them could decipher the

inscriptions. Mr. Huston allowed the stones to be forwarded to the Smithsonian in Washington D.C.,

where they are to be held for scientific investigation.

SMITHSONIAN BAFFLED BY INSCRIPTIONS

The authorities of the Smithsonian Institution state that the find is a remarkable one, and that they hope to

throw some light upon the meaning of the lettering etched upon the tablets. But, so far, however, they have

been unable to do so, or at least they have not announced the result of any discoveries, they may have

made in the matter.

THE DAVENPORT STELE

When the Davenport Stele is added to the mix, things get even stranger. The stele was found in an Indian

mound in 1877, and according to Harvard Professor Barry Fell, the stele contains writing in Egyptian,

Iberian-Punic, and Libyan. The Smithsonian, of course, says it and others like it are fakes.

SMITHSONIAN INVOLVED IN STRANGE ANCIENT IOWA

TABLET “HOAX”

WITH AMERICA B.C.’S BARRY FELL

BY OTTO KNAUTH

DES MOINES REGISTER, FEBRUARY 20, 1977

“Egyptian and Libyan explorers sailed up the Mississippi River 2,500 years ago and left a tablet where

Davenport now stands,” a Harvard Professor said. “That’s absurd,” countered a former Iowa state

archeologist, who says the Professor is perpetuating a 100-year-old hoax. Harvard’s Dr. Barry Fell, a

marine biologist by profession and an epigraphist by avocation, said he had deciphered the front and back

of a table that was found in an Indian mound in 1877. “The tablet,” he stated, “contains writing not only in

Egyptian hieroglyphics but also in Iberian-Punic and Libyan.”

He likened it in importance to the famed Rosetta Stone, which, because it said the same thing in three

languages, enabled scientists to decipher hieroglyphics.

“It is unquestionably genuine,” he stated.

“Not so,” said University of Iowa archeologist Marshall McKusick. “The tablet is part of ‘one of the

most thoroughly documented hoaxes in American archeology.’ Members of the old Davenport Academy of

Science inscribed the tablets and buried them in a mound on the old Cook farm, knowing the tablets would

be found by a member they wanted to ridicule,” McKusick says.

But the hoax got out of hand when the Smithsonian Institution got involved and the discovery of the

tablets received national publicity. McKusick documented the hoax in a 1970 book, The Davenport

Conspiracy.

“That all may well be true,” Fell said in a recent telephone interview, “and two of the three tablets in

the mound probably are fake. But the third, which he refers to as the Davenport Calendar Stele, definitely

is not.” This stele with the spring equinox scene on is described in Barry Fell’s book, America B.C., as

“one of the most important ever discovered. It is used in the ceremonial erection of a New Year pillar

made of bundles of reeds called ‘Djed,’” Fell said.

“Writing in the curving lines above says the same thing in Iberian and Libyan. The Egyptian

hieroglyphics along the top explain how to use the stone.

“Two Indian pipes carved in the shape of elephants found in the mound also are genuine,” Fell says.

BARRY FELL PUBLISHES CONTROVERSIAL AMERICA B.C.

Fell’s account of deciphering the tablet and the implications of its message are contained in his book just

published, America B.C.: Ancient Settlers in the New World. The book deals with a wide variety of

finds, particularly in New England, but also ranging as far west as Oklahoma, which Fell contends prove

that ancient Egyptians, Libyans, Celts, and other people were able to reach America and settle here well

before the birth of Christ. Portions of the book are reprinted in the February issue of Reader’s Digest.

“The Davenport stele,” Fell writes, “is the only one on which occurs a trilingual text in the Egyptian,

Iberian-Punic, and Libyan languages.

“This stele, long condemned as a meaningless forgery, is in fact one of the most important steles ever

discovered,” he writes.

“One side of the tablet—since its discovery it has separated by cleavage so that each face is now

separate—depicts the celebration of the Djed Festival of Osiris at the time of the Spring equinox (Mar.

21),” Fell says. The other side contains the corresponding fall hunting festival at the time of the autumnal

equinox (Sept. 21). The writing runs along the top of the spring tablet. “The Iberian and Libyan texts,”

Fell says, “both say the same thing—that the stone carries an inscription giving the secret of regulating the

calendar.” This “secret” is given in the Egyptian text of hieroglyphics.

“This Egyptian text,” Fell says, “may be rendered in English as follows”:

To a pillar attach a mirror in such a manner that when the sun rises on New Year’s Day it will cast

a reflection onto the stone called the Watcher. New Year’s Day occurs when the sun is in

conduction with the zodiacal constellation Aries, in the House of the Ram, the balance of night

and day being about to reverse. At this time (the spring equinox) hold the Festival of the New Year

and the Religious Rite of the New Year.

“This festival,” Fell says, “consists in the ceremonial erection of a special New Year pillar made of

bundles of reeds called a “djed.” The tablet, shows long lines of worshippers pulling on ropes with the

pillar in the center.”

HOW DID ANCIENT HIEROGLYPHS GET TO IOWA?

“How did this extraordinary document come to be in a mound burial in Iowa?” Fell asks. “Is it genuine?

“Certainly it is genuine,” he says, “for neither the Libyan nor the Iberian scripts had been deciphered at

the time Gass [Rev. Jacob Gass] found the stone. The Libyan and Iberian texts are consistent with each

other and with the hieroglyphic text.

“As to how it came to be in Iowa, some speculations may be made. The stele appears to be of local

American manufacture, perhaps made by a Libyan or an Iberian astronomer who copied as an older model

brought from Egypt or more likely from Libya, hence probably brought on a Libyan ship.

“The Priest of Osiris may have issued the stone originally as a means of regulating the calendar in far

distant lands. The date is unlikely to be earlier than about 800 B.C., for we do not know of Iberian or

Libyan inscriptions earlier than that date,” Fell writes.

“The explorers presumably sailed up the Mississippi River and colonized in the Davenport area,” he

says, and he hazards a guess that they came on ships commanded by a Libyan skipper of the Egyptian

navy, during the Twenty-second, or Libyan, Dynasty, a period of overseas exploration. “An Egyptian

astronomer-priest probably came with the explorers,” he speculates, “and it was he or his successors who

engraved the stone.

“The hunting scene tablet is engraved in Micmac script and is the work of an Algonquian Indian of

about 2,000 years ago,” Fell says. He does not explain the discrepancy in time, but goes on to say that the

Algonquian culture shows evidence of contact with early Egyptians. The approximate translation is:

Hunting of beasts and their young, waterfowl and fishes. The herds of the Lord and their young,

the beasts of the Lord.

“It is the earliest known example of Micmac script,” Fell says. Fell makes no mention in his book of

McKusick’s account of the Davenport fraud but this is not because he was not aware of it.

AVOIDING OLD DISPUTES

“I just felt it was kinder not to mention it,” he said recently. “It was my desire to avoid raking up old

disputes. Who cares whether somebody defrauded somebody else a hundred years ago? I attach no

importance to those things.”

NINETY-FIVE-PERCENT OF “FRAUDS”

TURN OUT TO BE TRUE

The Smithsonian, which was the first to declare the tablets fraudulent, had no experts in ancient languages.

“Only those who thought they were,” Fell said.

“And McKusick himself makes no claim to being a linguist,” he says. Fell said he has been

investigating similar archeological finds that had been labeled frauds, “and we find that 95 per cent of

them are genuine.

“There is a tendency on the part of those established in a field of science either to ignore or label as

fraud anything that does not fit in with their preconceived notion of how things should be,” he said.

“It is much easier to cry fraud at something out of the ordinary than to investigate it,” he said.

“Americans are throwing away 2,000 years of their history that way.”

Fell concedes he has never been in Iowa and was not allowed to see the tablet, which is now in

possession of the Putnam Museum in Davenport. He says he did his deciphering from photographs, which

is the usual way epigraphists do their work. McKusick has taken up the challenge by writing a report to

Science, the weekly publication of the prestigious American Academy for the Advancement of Science.

He said the Davenport frauds were first exposed in Science in the 1880s and later reviewed in 1970.

McKusick pointed out that the slate for one of the tablets (not Fell’s Davenport stele) came from a wall of

the Old Slate House, a notorious early-day house of ill fame. “The third tablet, a piece of limestone with a

tablet, is engraved on a piece of slate,” said University of Iowa Archeologist Marshall McKusick.

In 1970 McKusick wrote a book about the Davenport Conspiracy that surrounded the finding of the

tablets in an Indian mound in 1877. “Holes diameter and were used to hang the slate,” McKusick says.

Fell concedes this tablet may well have a fake figure of an Indian on it and came from Schmidt’s Quarry,

not far from the place where the tablets were found. The farm site now is occupied by the Thompson Hayward Chemical Co., 2040 West River Drive.

“A dictionary and almanacs provided inspiration for the writing on the tablets,” he said. “A janitor at

the Academy admitted carving various Indian pipes, which also were found in the mound,” McKusick

said. “They were soaked in grease or rubbed with shoe black to make them look old.” Two members of

the academy were expelled in the ruckus that followed the claims of fraud but a curious sidelight to the

controversy lies in the fact that none of the participants ever admitted in writing that they actually forged

the tablets. All were under threat of libel at the time. The closest thing to a confession in McKusick’s

book is a statement by Judge James Bellinger made in 1947 to a Mr. Irving Hurlbut. In it, Bellinger tells

of copying hieroglyphics out of old almanacs on slate he tore off the wall of the Old Slate House.

The story becomes suspect, however, when McKusick points out that Bellinger was only 9 years old at

the time the tablets were found. “Whatever the judge may have said, he was nowhere near the scene of the

events he so vividly describes,” McKusick wrote.

“GULLIBLE PUBLIC”

In his report to Science McKusick says of the Fell book: “It is an unfortunate imposition upon a gullible

public to have the Davenport frauds accepted as genuine and used to explain Egyptian explorations up the

Mississippi 3,000 years ago.

“Fell, as a ‘Harvard scholar,’ has a scholarly responsibility to know the professional literature on

subjects he is publishing theories about. His book, America B.C., is irresponsible amateurism and is

unfortunately but one example of a genre of speculation that is growing and sells well to the public.”

“Modern technology may provide the means for resolving the issue of whether one or all of the tablets

are fake,” says Dr. Duane Anderson, who succeeded McKusick as state archeologist. “If the tablets could

be submitted to a rigorous microscopic examination, it might be possible to determine that the writing is

older than a mere 100 years,” Anderson said. “Rock ages, and often a patina, or microscopic crust,

develops on the surface. It might also be possible to detect traces of modern steel if the incisions were

made with modern instruments,” he said. Anderson continued, “But they might at least be able to reveal if

the writing was done before 1877.”

Anyone wishing to make such an examination will have to secure the cooperation of the Putnam Museum, which is the present custodian of the tablets. Museum Director Joseph Cartwright has steadfastly

refused access to the tablets, saying they have “been removed from the museum collection.

“We are not anxious to dig up the whole controversy again,” he said in a recent telephone interview. “It

is not in the museum’s interest to make them available. This is something the museum is not interested in.”

Asked if it might not be interesting for the public to put the tablets on display in view of the present

renewal of the controversy, Cartwright replied, “It is our prerogative to decide, not yours.”

HIEROGLYPHIC TABLETS IN

MICHIGAN AND KENTUCKY

Evidence of writing and hieroglyphs has been found all over the country, attesting to widespread trade

and wide-ranging cultural influences. Many examples have been found in Michigan, including the

controversial Michigan tablets, which number in the thousands. Many more finds of writing have been

discovered across the country, although many, like the Ten Commandments from Ohio and the Michigan

and Illinois tablets, are still under hot dispute. Here are two finds from Michigan and Kentucky that

appear genuine.

ANCIENT HIEROGLYPHICS AND WRITING ON A TABLET

DETROIT FREE PRESS, JUNE 14, 1894

The mounds on the south side of Crystal Lake, in Montcalm County, Michigan, have been opened and a

prehistoric race unearthed. One contained five skeletons and the other three. In the first mound was an

earthen tablet five inches long, four wide, and half as much thick. It was divided into four corners. On one

of them were inscribed queer characters. The skeletons were arranged in the same relative positions, so

far as the record is concerned.

In the other mound, there was a casket of earthen ware ten and one half inches long and three and a half

inches wide. The cover bore various inscriptions. The characters found upon the tablet were also

prominent on the casket. Upon opening the casket, a copper coin was revealed, together with several

stone types, with which the inscriptions or casket had evidently been made. There were also two pipes

—one of stone, the other of pottery and apparently of the same material as the casket.

STRANGE ANCIENT WELSH MESSAGE WRITTEN ON A STONE?

PROCEEDINGS OF THE ANCIENT KENTUCKY HISTORICAL SOCIETY, FEBRUARY 11, 1880

Craig Crecelius made a curious discovery in 1912, while plowing his field in Meade County, Kentucky.

He had unearthed a limestone slab that had strange symbols chiseled onto the rock face. Knowing that he

had made an important historical find, he sought information about the origins of the stone from the

academics.

For over 50 years, Crecelius inquired of anyone with academic credentials about the significance of the

carved symbols. Typical of the comments he received from the “experts” were like what one geologist in

1973 remarked that the rock was “geologic in origin” and “not an artifact.” An archaeologist has said that

the carvings were grooves created by shifting limestone pressures. [ a paper on this stone d.c ]

Disheartened and tired of being made fun of by the locals, Crecelius finally gave up his quest for

finding out the rock’s secrets. In the mid 1960s, he allowed Jon Whitfield, a former trustee of the Meade

County, Kentucky, Library, to display the stone in the Brandenburg Library. This could very well have

been the end of the story, had it not been for the observant Mr. Whitfield.

Whitfield attended a meeting of the Ancient Kentucky Historical Society (AKHS) and saw slides of

other, similar-looking carved stones. He learned that the carvings were a script called Coelbren, used by

the ancient Welsh. Whitfield was informed that similar stones had been widely found across the south central part of the U.S. Pictures made of the Brandenburg Stone were submitted to two Welsh historians

helping the AKHS in deciphering the scripts.

Alan Wilson and Baram Blackett, specialists in the study of the Coelbren script in Wales, immediately

were able to read the script. The translation is intriguing; it appears that the stone may possibly have been

a property or boundary marker: “Toward strength, divide the land we are spread over, purely between

offspring in wisdom.”

Wilson and Blackett place a connotation of the promotion of unity with the phrase “Toward strength”

and a connotation of justice with the word “purely.” The stone was on public display from 1999–2000 at

the Falls of the Ohio State Park Interpretive Center in Clarksville, Indiana. The display has since been

moved to the Charlestown Public Library, Clark County, Indiana.

ANCIENT COINS FOUND IN AMERICA

Scattered reports of ancient coins found buried around the country are usually dismissed as fraudulent by

traditional archaeologists, but in the collection of stories that follow, one outlines a circumstance where

the difficulty of creating a hoax belies that idea, while others tell of quite recent finds that have been

authenticated by ancient coin experts.

The following first-person account of the discovery of two ancient coins is very instructive. The coins

were found underneath the roots of a beech tree that had been blown up in order to clear a field. This is

not something that could be done as a prank, as the entire operation would have been costly and pointless

in the extreme.

The Natural and Aboriginal History of Tennessee, 1823

BY DR. JOHN HAYWOOD

A Copper Medal of King Richard III Found

Between the years of 1802 and 1809, in the state of Kentucky, Jefferson County, on Big Grass Creek,

which runs into the Ohio River at Louisville, at the upper end of the falls, about ten miles above the

mouth, near Middleton, Mr. Spear found under the roots of a beech tree, which had been blown up,

two pieces of copper coin of the size of our old copper pence. On one side was represented an eagle

with three heads united to one neck. The sovereign princes of Greece wore on their scepters the

figure of a bird and often that of an eagle. Possibly this may have been a coin uttered in the time of the

three Roman emperors.

Lately, a Cherokee Indian delivered to Mr. Dwyer, in the year 1822, who delivered to Mr. Earle, a

copper medal, nearly or quite the size of a dollar. All around it, on both sides was a raised rim. On

the one side is the robust figure of a man, apparently of the age of 40, with a crown upon his head,

buttons upon his coat, and a garment flowing from a knot on his shoulder, toward and over the lower

part of his breast, his hair short and curled; his face full; his nose aquiline, very prominent and long,

the tip descending very considerably below the nostril; his mouth wide; the chin long, and the lower

part very much curved, and projected outwards. Within the rim, which is on the margin, and just

below it in Roman letters, are the words and figures: “Richardus III. DG. ANG. FR. Et HIB. Rex.”

The letters are none of them at all worn. Both the letters and figures protuberant from the surface.

On the other side is a monument with a female figure reclined on it, her knees a little raised, with a

crown upon them, and in her left hand a sharp pointed sword. Underneath the monument are the

words: “Coronat 6h Jul, 1483.” And under that line: “Mort 22 Aug. 1485.”

Of Their Coins and Other Metals

About the year 1819, in digging a cellar at Mr. Norris’s, in Fayetteville, on Elk river, which falls into

Tennessee, and about two hundred yards from a creek, which empties into Elk, and not far from the

ruins of a very ancient fortification on the creek, was found a small piece of silver coin of the size of

a nine-penny piece.